“It Happened”: Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard’s Road Trip Film

PDF: Shea, It Happened

In 1948, Simone de Beauvoir took a four-month road trip across the United States. In the preface to her subsequent memoir, America: Day by Day (1953), Beauvoir explains that she adopted a diaristic mode because she did not want to eliminate the crucial factors of her subjectivity, specific vision, and personal preferences. Beauvoir writes:

Although it was retrospectively written, this journal, reconstructed with the help of some notes, letters and still-fresh memories, is scrupulously exact. . . . There was no process of selection involved in the development of this story. It is the story of what happened to me, neither more nor less. This is what I saw and how I saw it; I have not tried to say more. . . . Words, images, knowledge, effort would serve no purpose; to say they were true or untrue [would be] meaningless; they existed in another way here.1

Beauvoir both contends that her writing is “scrupulously exact” and suggests that distinguishing the events as true or untrue is “meaningless.” Beauvoir’s “what happened” includes what she has witnessed and allows space for the embodied experience of a road trip. It encompasses things seen and things felt.

On the morning of January 3, 1992, French artist Sophie Calle and US director Greg Shephard left New York, driving south and west, on a road trip that led to the production of the 76-minute film No Sex Last Night (Double Blind) (1992), shakily filming themselves and each other as they figured out how to work their brand-new handheld video cameras.2 Calle and Shephard took their American road trip more than forty years after Beauvoir’s, but Beauvoir’s memoir and her account of “what happened” provides a feminist framework for understanding Calle’s formal choices in producing the film. The film’s blurry imagery and indistinct narrative reflects the nature of Calle and Shephard’s relationship—that is, their inability to understand themselves or each other and a general lack of vision for their future. Each morning, Calle dejectedly pronounces, “No sex last night,” while a grainy still of an empty, unmade motel bed occupies the screen (fig. 1). In voiceovers, Calle reveals her frustrations with Shephard’s silence, his lack of sexual desire, and his obsession with his old Cadillac, which is constantly in need of costly repairs. Meanwhile, Shephard narrates into his camera feelings of depression, entrapment, and annoyance with Calle’s dismissive and ironic attitude.

Shephard concludes the film with a contradictory sentiment: “It’s become a matter of which truth to tell. At least now, I’m giving myself a chance to, for the first time, do what I’ve always wanted to do: to try to tell an honest story.” With the film, he needed to decide both “which truth to tell” and how “to tell an honest story,” implying that honesty may not be equivalent to truth.

This detail is striking because Calle regularly faces questions about how true the stories are in her autobiographical, photo-textual works, which are based on herself or her relationships with others. Accompanied by precise, formal text, her seemingly banal images come alive with often outlandish, overly serendipitous stories that are so deeply intimate they prompt critics, curators, and the public alike to ask, “Is that really true?” I am less interested in searching for where Calle’s life stops and her art starts and more intrigued by how she mobilizes truth as a key element in her oeuvre, from No Sex Last Night to True Stories, a conceptual text that she continues to publish. This essay presses on how and why Calle turns to her road-trip film specifically, the only road-trip project and the first film she made, to illustrate her artistic relationship to autobiography and the relationship between fact and fiction.3 I then show how Calle’s film embodies a feminist vision of the road trip; that is, a visualizing of the American road trip that is premised on documentary principles of truth telling while also privileging what Donna Haraway has theorized as the partial vision of situated knowledge.

It Happened

In an interview with Jill Magid from 2008, Calle uses No Sex Last Night (Double Blind) to illustrate how she conceptualizes “truth” in her work. When Magid asks what role fiction plays in her autobiographical projects, Calle responds:

It’s complicated what fiction is, because everything is fiction, in a way. Take the example of the movie No Sex Last Night (1992), because that’s the easiest one. The trip lasted three weeks, the man I stayed with one year, the movie is one hour. We could have done one hundred, two hundred, three hundred absolutely different movies, all being through editing the moment you choose. In a way, I don’t have the capacity of invention. If I could invent, why not? Except, I don’t.4

Calle again cites the film when asked by Louise Neri in Interview in 2009 about her artistic responsibility to truth telling:

Take the movie No Sex Last Night [1996] that I made with my then-husband Greg Shephard: We lived together for one year; we filmed 60 hours; of those 60 hours we chose just 90 minutes. . . . We chose to put the emphasis on me and my solitude and him and his car, whereas we could have chosen to speak only about food, or only about traveling cross-country, or only about the disgust we had for each other, or only about the beautiful moments we shared. So any one version is never “true,” it just works better than another. But I can say that it did happen. True? No. It happened.5

I argue that, for Calle, the “it happened” she references is the content, the performed rituals, of the trip—stopping at a garage, eating at a restaurant, sleeping at a motel, not having sex, driving in silence, having a wedding. But beyond what happened, the truth, for Calle, is the totality of the embodied experience of the American road trip wherein the truth does not require a chronological narrative or geographic certainty. Calle openly rejects the idea that truth has any sort of monopoly over her creative process. Thus, on the one hand, through straightforward language and the use of a documentary style in her photography and film, Calle points to the “truth.” But on the other hand, as curator Lawrence Rinder explains, Calle also “cultivates doubt. . . . [She] makes us question the purpose of knowledge itself. Her beliefs are not so much held as floated, like trial balloons that pop as soon as they are examined too closely.”6 Calle uses daily rituals to show what happened and a filmic style permeated by gaps, lapses, ambiguity, partiality, and mediated self-imaging to show what, in a holistic way, it really was like.

Haraway’s 1988 article “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective” is useful here. Haraway rejects the idea that any sort of pure objectivity exists in science and visualization technologies, writing, “Only partial perspective promises objective vision . . . feminist objectivity is about limited location and situated knowledge, not about transcendence and splitting of subject and object.”7 She argues for this view of partiality from an always and already complex and contradictory body located somewhere—not nowhere nor everywhere.8 Situated knowledge is the central concept of feminist epistemology and refers to how knowledge is socially situated. It reflects the lived experiences and perspectives, including gender and other factors of marginalization, of each person. Calle and Beauvoir’s “it happened” / “what happened” might be considered, then, as expressions of the feminist road-trip vision. Feminist road-trip vision does not describe an essentialist view that women see like this but suggests that the particular space of a car on a road trip can be disorienting and that by embracing transience, this kind of vision, following Beauvoir and Haraway, can overcome the downsides of both totalization and relativism.9 In Calle’s and Beauvoir’s own ways, they report back about their trips with an acknowledgment that the events are not the full truth of their experiences.

No Sex Last Night (Double Blind) was banal, boring, amateur, and lacked impressive vistas. Yet, with its pervasive visual and narrative uncertainty, the film can be interpreted through an undercurrent of a partial and situated approach. While the “what happened” is a bridge from Beauvoir to Calle, it is also a question: what happened?

What Happened?

For most of Calle and Shephard’s drive, no singular narrative emerges, only half-stories and memories. Uncertainty pervades and storylines intersect as the pair drive through largely unrecognizable landscapes. Calle and Shephard have trouble connecting, and they retreat to telling stories about themselves to their own cameras rather than to each other. After all, the film’s secondary title, Double Blind, refers to a type of experiment where neither the participants nor the researchers know which group is the test and which the control until after the experiment is complete. Is Shephard the test group? Is Calle the control? What about the viewers?

The film’s narrative confusion mirrors its disorienting visual components. Three days into the trip, Calle and Shephard replayed what they had on a television in one of their motel rooms and realized that their footage was too shaky.10 In an interview with Lynne Cooke about the video, Calle and Shephard elaborate on their inexperience with the video cameras. Calle admits, “When we watched the results of the first few days of recording, we were desperate. . . . Everything that was shot in the street, in the hotel, in the motel was impossible to use so we thought the movie was finished. Then we realized that, if we froze the images, we were saved.”11 The effect is disconcerting: when Calle and Shephard are stationary, the images move, and when they move, the images are still.

While viewers can piece together that Calle and Shephard are driving south from New York City and then west, their route otherwise remains vague to any viewer without a map at hand. There is a sense of geographic unknowability that works in tandem with the filmic style. Occasionally they mention small towns, like Fair Hope, Chromo, and New Iberia. But, most of the shots are of generic US motels, diners, and mechanic shops, making their exact locations hard to place. For example, in a still of a motel room, the white telephone, brass lamp, laminate table, and floral bedspread resemble furniture items that could potentially be from a motel room anywhere in the United States (fig. 2). Furthermore, the camera faces the wall, not a window, emphasizing the closed-in nature of the space rather than any exterior sights that might situate the viewer. A still from a diner shows the remnants of a typical American roadside meal: a droopy tomato has been taken off a burger and is left on the side of the plate along with leftover onion rings and a plastic cup (fig. 3). Calle and Shephard see the United States through its restaurants, garages, motels, and occasionally landscapes, but often in the dark and only mediated through the lenses of both a windshield and a video camera.

The passage of time is also unclear. Calle and Shephard complete a lot of driving at night, sometimes through snow, adding to the sense of disorientation. Once they start driving west, the date stamps disappear from the screen completely, replaced by time stamps: viewers may know it is 2:56 a.m., but on what day or where remains elusive. At one point, Shephard even asks Calle, “Is it still Saturday?” There are also several costly automobile breakdowns and repairs referenced in the film, and so the pair spend a lot of time waiting. As Calle describes in a voiceover, the stops are “garage, restaurant, garage, restaurant, garage, restaurant, garage.” The car—and the couple—are frequently stuck. The film thus stresses the disorientation of long, exhausting road trips and their resultant strange sense of time, banality, and repetition.

Surprisingly, considering the titular lack of sex or any emotional or physical intimacy between Calle and Shephard, the climax of the film occurs in Las Vegas, Nevada, when the couple decides to marry at a twenty-four-hour, drive-through wedding chapel on South Las Vegas Boulevard. Calle is shocked that Shephard agrees to her idea. The wedding is the longest and best-documented scene in the film: Calle and Shephard are shown filling out paperwork for the marriage license, eating a prewedding meal, and participating in the ceremony, performed at a drive-through window by a minister while the couple stays in the car, camera on the back of the convertible. They exchange vows and then a kiss (fig. 4). Cutting through loud road noise from the Las Vegas strip, viewers can hear an “I pledge” or a “with this ring, I thee wed,” but the scene largely relies on the visual over aural to communicate the narrative.

That night, they leave Las Vegas and sleep in the car—and still, no sex. The day after their wedding, they reach Los Angeles and abandon Shephard’s Cadillac as it finally breaks down beyond repair. They finish the last leg of the trip, from Los Angeles to Oakland, in a rental car. But one more major plot point occurs, on the morning of January 20: the customary daily shot of an unmade hotel bed, always accompanied by a verbal “No” from Calle, is finally accompanied by a simple “Yes,” indicating sex was had that night. Later that day, they reach their destination, Mills College, and are shown, in a still image, entering a home together.

A text panel reading “Three months later” flashes across the screen, and viewers get an update on the couple’s lives through two, separately narrated endings. Calle discusses her initial period of marital bliss living in Oakland, followed by intense jealousy after finding letters in the couple’s car that Shephard had written to another woman. Shephard notes the efforts he took to make the relationship work while, admittedly, still lying to Calle about seeing someone else. A divorce is hinted at but not directly stated. Rather, that information is revealed by Calle in a future project, her photo-textual work True Stories, discussed below.

Situated Knowledges

The wedding scene exemplifies how the knowledge produced from within the car is both situated and partial but still offers a wider vision of Calle and Shephard’s experience. It is also the climax of the film. Viewers do not know why Calle wants to marry Shephard, only that she has a strong desire to be married. It is unclear if this is merely an artistic stunt. However, all the scenes showing state paperwork and official documentation make it seem like the marriage actually occurred. Shephard, for example, spells out his full name for the marriage license. Even though the cameras roll during the wedding scene, they get married in a parked car. They are not going anywhere. Marriage is their way of trying to legally solidify an ambiguous relationship and give it some shape. Marriage is a legal form of truth that does not necessarily reflect the truth of an intimate relationship. The legality of the wedding is a way to fix a shaky relationship with too many moving parts. And, viewers learn later, soon after they stop moving—that is, stop traveling and stop making the film—their relationship ends.

However, the documentary evidence for the marriage is accompanied by aural uncertainty. Viewers rely on bad audio from the handheld cameras, which do not deliver clear dialogue, especially near a busy road. In a voiceover, Shephard acknowledges he cannot hear the minister but reminds himself to smile and nod. The soundscape is full of dull background traffic and car horns, without the vocal clarity of a typical indoor wedding. Viewers witness the exchange of vows, but the difficulty of hearing the words makes the scene lack the kind of strong witnessing power it might otherwise have. This negotiation between truth and ambiguity, between visual clarity and aural uncertainty, between Calle and Shephard, is not meant to trick us: rather, ambiguity and situated knowledge are visual and narrative strategies used to bring viewers closer to the actual filming, to the characters’ physical experiences, to the narrating and editing of the video itself. The simultaneous use of documentation and obfuscation reveals, on the one hand, a desire to experiment with photography’s truth claims and, on the other, with the fluctuating vantage points and embodiment inherent to road travel.

Haraway’s theory of situated knowledge also addresses how knowledge production is, in part, created by striking up “non-innocent conversations by means of our prosthetic devices, including our visualization technologies.”12 Along with the video cameras, Calle and Shephard’s mobilities are determined, in part, by their vehicle: the large size, the shape, and the failing mechanics of the 1960s Cadillac DeVille convertible (fig. 5), with its huge windshield, top-down option, and large autobody shape, which influences the kind of vision and experiences possible within it. The car is like a third main character. Constantly breaking down, the Cadillac has mechanical failures that cause their trip to start and stop, dragging on much longer than anticipated, as they spend hours waiting for mechanics to make repairs. Nevertheless, its roomy interior, large windshield, and windows affect the pair’s physical and visual experience. The car allows them to sleep rather comfortably within it, to meet several strangers interested in the vehicle, and to experience the drive-through wedding celebration.

The film also depicts Shephard in love with the car rather than with Calle, referring to it as “Honey.” “Come on, Honey,” he says, while Calle deadpans into her camera, “That was nice. Only it is to his car.” At another point, Calle turns around to look at Shephard’s camera and says, disappointed, “I thought he was filming me, not the car” (fig. 6). Shephard defends the car from criticism, blaming the rain, for example, for its breakdown instead of his own lack of preparation for a long road trip. Shephard, otherwise depicted as a fragile person with poor communication skills and low self-esteem, locates his masculinity in the vehicle, whose stops, stutters, and needs for repairs demand attention as much as he does. A feminist road-trip vision considers how the car and its occupants are situated but not stagnant, embracing not just the events of the trip but the strangeness of how it felt, looked, and sounded, too.

True Stories?

In 2008, critic Chris Townsend termed Calle’s propensity for elaborate exhibitions of her autobiographical work as “narcissistic horror.”13 Calle’s art practice is centered around herself (and/or the character she plays of herself), but his use of the term “narcissism” is gendered and predictable. Townsend associates a woman’s autobiographical artistic project with selfishness, self-centeredness, and narcissism rather than the male gendered equivalent, namely genius.

Traveling women, specifically, have had a particularly negative reputation in this regard. During the twentieth century in the United States, as Sidonie Smith shows, traveling women were perceived as occupying “an unbecoming subject position” because they were away from the home. Earlier, in the nineteenth century, women’s travel narratives “often masked their agency by omitting ‘I,’ [not] talk[ing] about erotic encounters, [and] apologiz[ing] for repeating men’s narratives,” reserving the first-person “I” only for the footnotes, for example.14 In contrast to the repressive history of women voicing their personal and intimate experiences in travel narratives, Calle’s road film is titled after her own unfulfilled sexual desire. While intimacy might be her ultimate goal, sex is her declared one and something she obsesses about throughout the entire film, much to Shephard’s chagrin. There are shots of her hanging around the hotel room naked, asking about sexual aspects of Shephard’s dream life. She not only talks about her lack of erotic encounters on the trip, proclaiming over a dozen times in the film that no sex was had, but she also overtly describes sexual fantasies she has to Shephard as if to egg him on. In the scene right before they get to Las Vegas, Calle bites on chocolate while trying to engage Shephard in a discussion about her failure to remember her former lovers’ penis sizes. But, at the same time, she desires traditional notions of marriage and domesticity; right after the wedding she declares, “I will never again be an old maid,” and later, “I was happy. He had stayed with me and said now and then ‘My wife Sophie.’” The self-portrait Calle creates defies and deflects binaries often placed on female bodies, identities, and desires.

However, the completion of the film does not mark the end of the narration of the trip or its role in her autobiographic works. After Calle and Shephard completed their film, Calle published the first version of her photo-textual book Les Autobiographies (True Stories) (1992), a collection of images paired with text from Calle’s “real life,” available in French and English, in both print and exhibition formats.15 Every edition, the sixth and most recent released in 2018, gets progressively longer as recent stories are added to each new edition; older stories are not edited, but in a few cases, they are removed.

Photographs in True Stories reference No Sex Last Night (Double Blind), unbeknownst to most readers. Every edition includes a section called “The Husband,” made up of ten short stories and corresponding images, what scholar Johnnie Gratton calls “photobiographical units.”16 Although No Sex Last Night is not named in True Stories, the ten stories address the events that occur before, during, and after filming, such as how Calle and Shephard met in a bar, planned and took the road trip, married in Las Vegas, and divorced. Calle’s emotional recovery from the demise of the relationship is the subject of the last of the ten stories, the only one in which she mentions Shephard by name (and only by his first name, Greg).

Calle does not reuse the stills from film in True Stories. Rather, she mainly takes new photographs and, in one instance, borrows a photograph from a different project to retell the story of her relationship, the road trip, and its aftermath on her own terms.17 All the photographs in “The Husband” are black and white, while the film is in color. Still photographs based on moving images are recreated in the pages of True Stories. Calle’s transitions among stills, film, and photographs, together with voiceovers, subtitles, and text panels, are choices of medium that reflect her nebulous relationship to truth and fiction, too. Her disregard of medium specificity to tell a story reinforces the ease with which she moves between “truth” and “happening” that continues from No Sex Last Night into True Stories. The format of the photographic book demonstrates the allure of still photography: simultaneously real and fake, its contents are able to be endlessly reproduced in editions and exhibitions. With its still images, controlled text, increased audience accessibility, and long-gone collaborator, the photobook fulfills Calle’s desire for total control of vision; she is off the road.

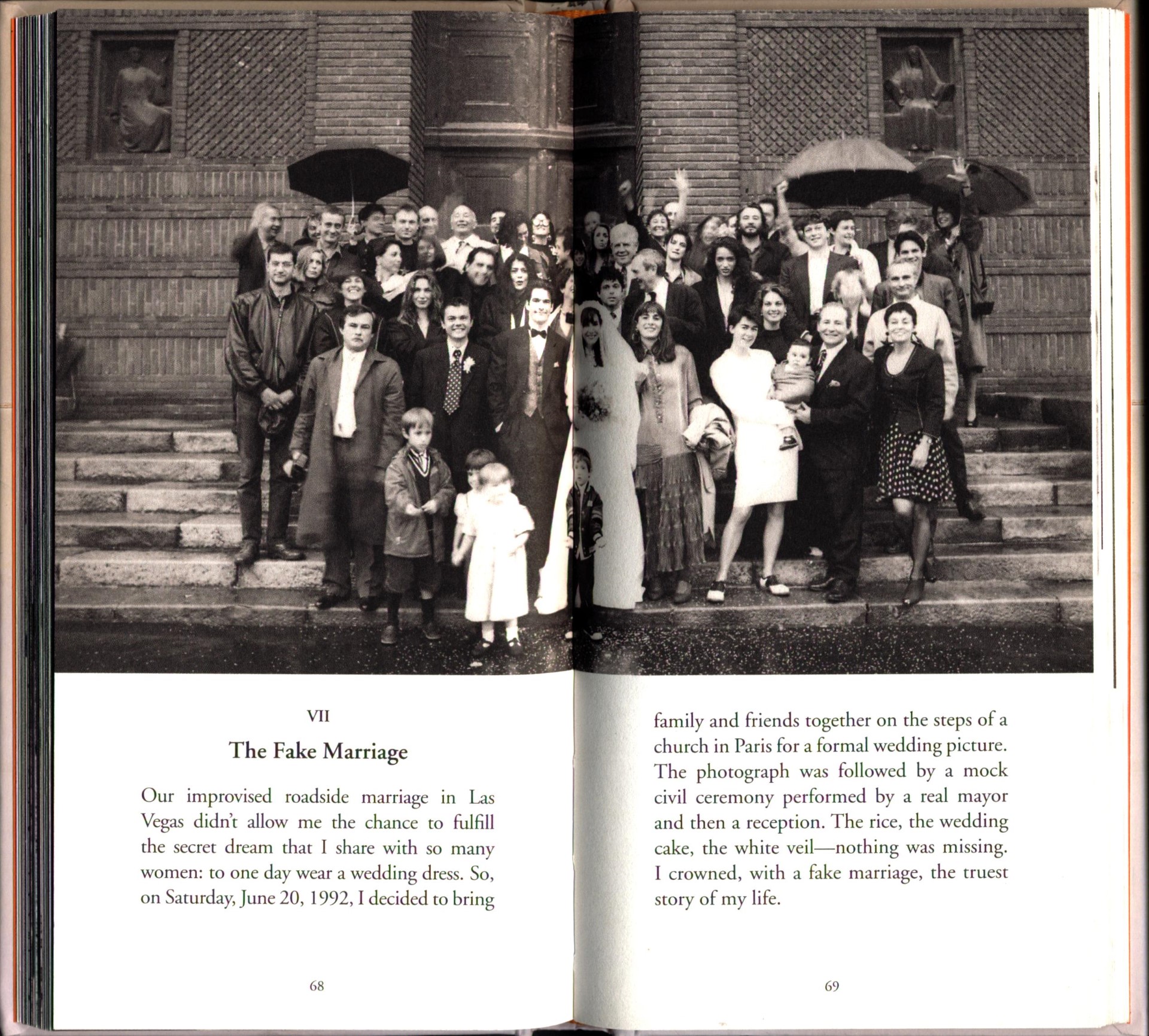

For example, the seventh story in True Stories’ “The Husband” section is titled The Fake Marriage. It involves a staged wedding photograph taken on the steps of a church in Paris, showing Calle and Shephard surrounded by family and friends, several months after their Vegas wedding (fig. 7). In No Sex Last Night, the same photograph flashes briefly at the end of the film when Calle recites her final voiceover and discusses their trip together to France. In True Stories, the accompanying text tells us that the wedding was a “a mock civil ceremony performed by a real mayor.”18 The photograph The Fake Marriage is a prime example of a Calle-esque “it happened” moment—real but not true.

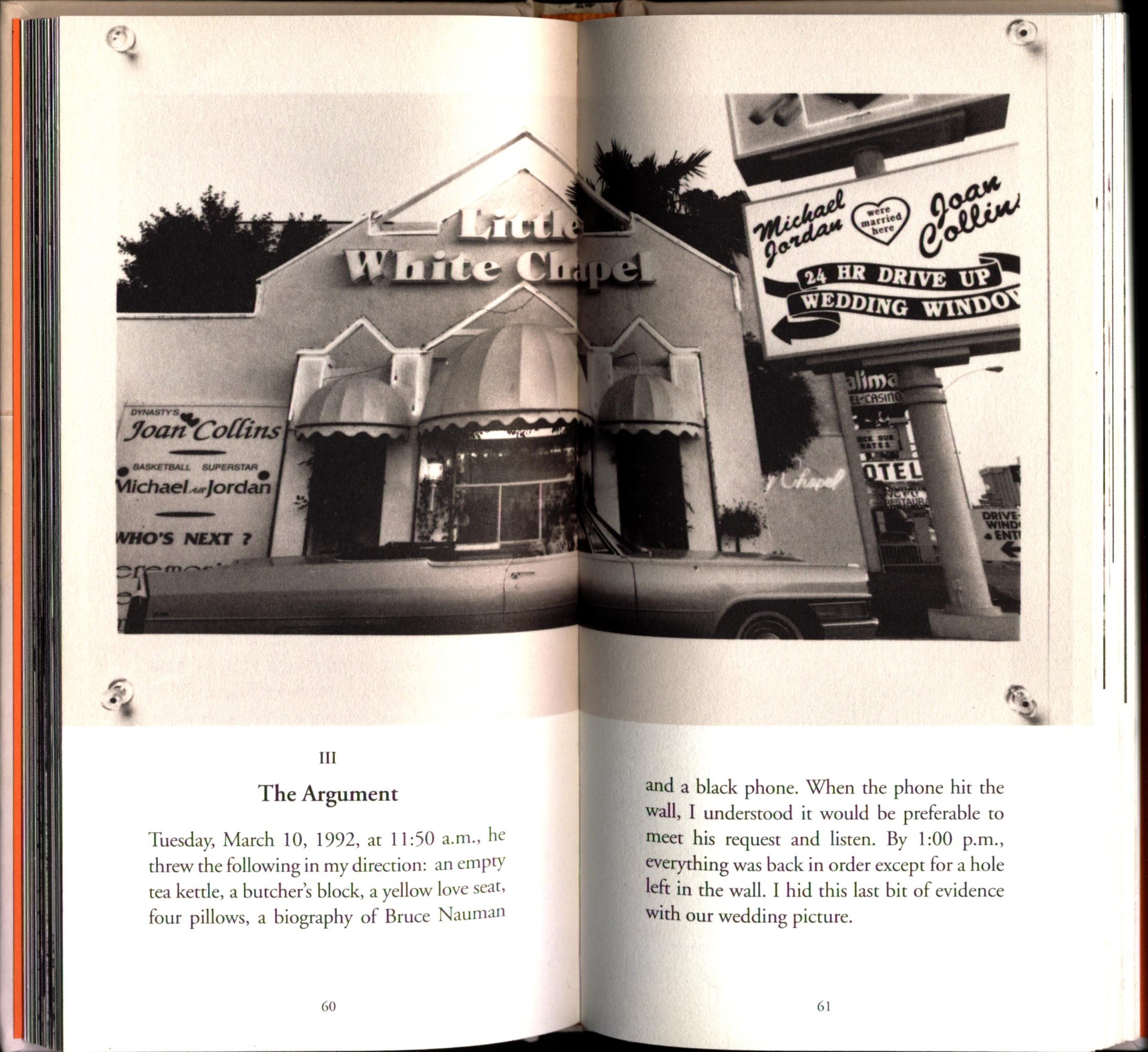

Calle’s fragmented self is thus transposed from the film to photography and text, in stories that are themselves repeated, partial, and ambiguous. The Argument shows Calle and Shephard sitting in the Cadillac, its top down, directly in front of their Las Vegas wedding venue, the Little White Chapel (fig. 8). This is the wedding photograph that “happened” on their road trip but was insufficient in fulfilling Calle’s desire to wear a wedding dress and be photographed, a desire fulfilled in The Fake Marriage. However, True Stories makes clear that the couple’s split is imminent: Calle describes how she used this, their “real” Vegas wedding photograph, to cover up a hole on the wall caused by Shephard throwing a phone during a fight—a scene not addressed in the film. As Beauvoir suggests to her readers in The Second Sex, “Marriages are not generally founded upon love.”19

Calle’s photo-textual units pull viewers into her game; they ask us to realize that she is faking it—really. The collaborative No Sex Last Night (Double Blind) ultimately fails at fully realizing Calle’s “it happened,” evidenced by the many editions of True Stories she published after the fact. For “it happened” to be best represented, she had to reproduce the story of the film in a different format, and to do so multiple times. For Calle, a truer feminist road-trip vision needed to be represented across media and multiplied over time to reflect the embodied experience of boredom, love, and heartbreak that she experienced on the road. Ambiguity, instead of blocking access to truth, can be a form of situated truth telling. In True Stories, her “it happened’ is now still, tangible, and forever her version(s) of the truth—and still full of gaps.

Cite this article: Laura Elizabeth Shea, “‘It Happened’: Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard’s Road Trip Film,” in “Reconsidering Art and Travel in America” (In the Round), ed. David Smucker, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18291.

Notes

- Simone de Beauvoir, America: Day by Day, trans. Patrick Dudley (New York: Grove, 1953), ix, 12, emphasis added. ↵

- Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard, dir., No Sex Last Night (Double Blind) (1992), 76:00 min., color, sound, English and French with English subtitles. ↵

- Subsequent Calle films are: Sophie Calle and Fabio Balducci, dir., Unfinished (2005), 30:14 min., color, sound, English and French with English subtitles; and Sophie Calle, dir., Couldn’t Capture Death (2007), 12 min., color, sound. ↵

- Calle quoted in Jill Magid,” Sophie Calle,” in Sophie Calle: The Reader, ed. Andrea Tarsia (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2009), 143–44. ↵

- Sophie Calle, interview with Louise Neri, Interview (March 2009), https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/sophie-calle, emphasis added. Note that the year 1996 is sometimes cited as the release date of the film, but it was completed in 1992 and premiered in 1993 at the Whitney Biennial. ↵

- Lawrence Rinder, “Sophie Calle and the Practice of Doubt,” in Sophie Calle: Proofs (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 1993), 12. ↵

- Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Fall 1988): 583. ↵

- Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 589. ↵

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. H. M. Parshley (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1957), xxix. ↵

- Hans Ulrich-Obrist, “Portrait of Sophie Calle,” in Tarsia, Sophie Calle, 134–35. ↵

- Sophie Calle, quoted in Lynne Cooke, “Double Blind: An Interview with Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard,” Art Monthly 163 (February 1993): 409. ↵

- Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 594. ↵

- Chris Townsend, “Knowledge as Spectacle,” Art Monthly 322 (December 2008–January 2009): 13. ↵

- Sidonie Smith, Moving Lives: 20th-Century Women’s Travel Writing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001),18n16. For other examples, see Anna Maria Falconbridge, Narrative of Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone (London: L. I. Higham, 1802); and Sarah Lee, in Stories of Strange Lands and Fragments from the Notes of a Traveller (London: E. Moxon, 1835). ↵

- The series has also been exhibited and published as Des histoires vraies and The Autobiographies. ↵

- Johnnie Gratton, “Sophie Calle’s Des histoires vraies: Irony and Beyond,” in Phototextualities: Intersections of Photography and Narrative, ed. Alex Hughes and Andrea Noble (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), 183. ↵

- The photograph used for “The Erection” is not from No Sex Last Night (Double Blind)but comes from her earlier project The Hotel (1981), in which Calle worked as a chambermaid in a Venetian hotel and photographed visitors’ belongings. ↵

- Emphasis added. ↵

- Beauvoir, Second Sex, 434. ↵

About the Author(s): Laura Elizabeth Shea is Assistant Professor in the Fine Arts Department at Saint Anselm College, Goffstown, New Hampshire.