Paperwork: Bureaucracy and Legibility in a WPA Portrait

PDF: Joyce, Paperwork

![Black-and white lithograph of a woman's profile. She has dark hair swept away from her face and large eyes. Underneath, to the left is written "T[ill.] Osato"; to the right is "Dorothy Jeakins ® 1936."](https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/word-image-19914-1-scaled.jpeg)

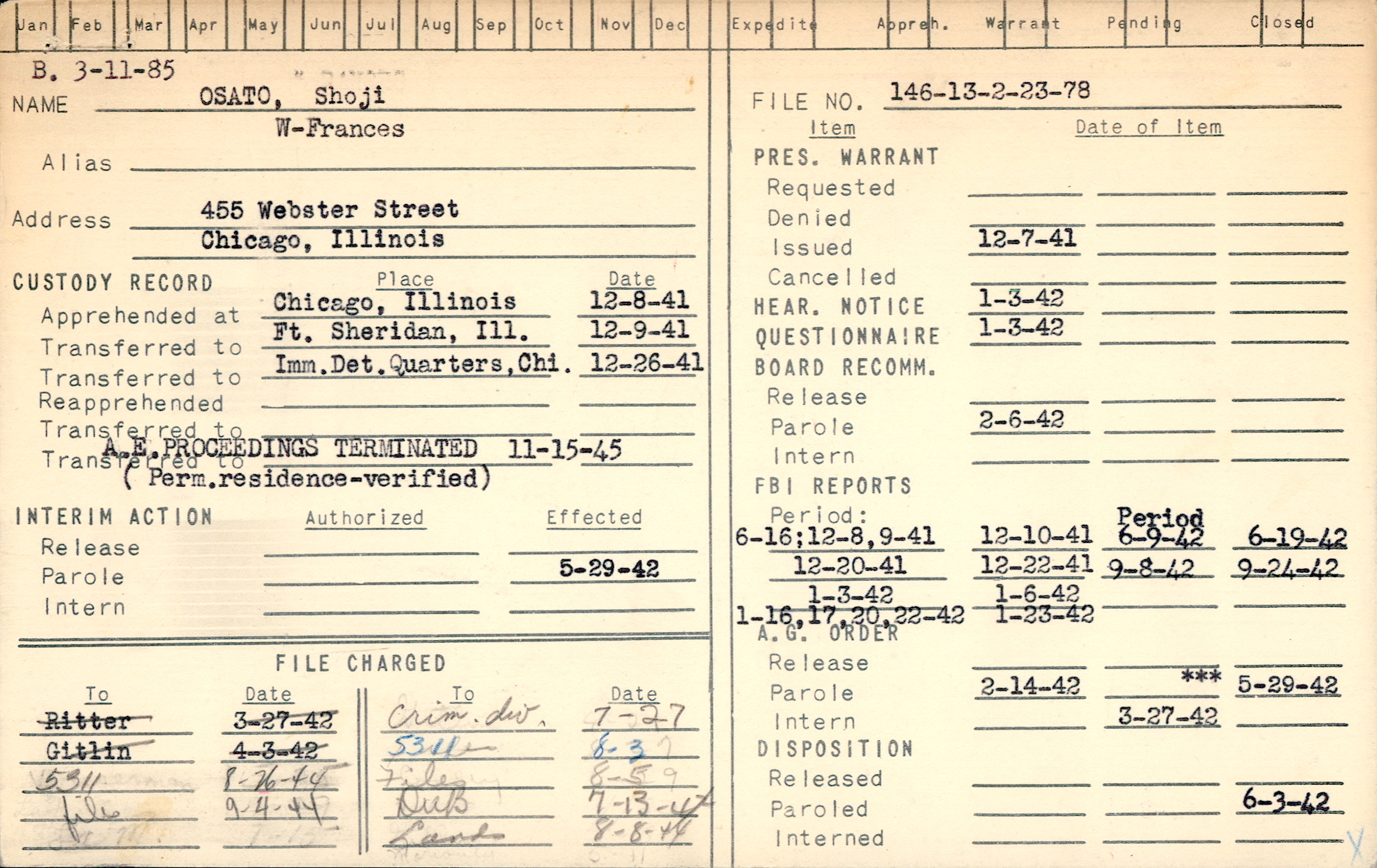

The lithograph previously catalogued as Taro Osato is a portrait of a young woman facing right (see fig. 1). Dorothy Jeakins (1914–1995), the printmaker, traces the sitter’s profile with a stark curving line. A few strands of hair escape her swept-back tresses, trailing over her ears. Her eyes are dark and large, taking up much of her face. A ghostly outline hovering above the subject’s upper lip and an overextension of her mouth, both partially effaced, signal the relative inexperience of the printmaker as well as the fact that this portrait was composed directly on the limestone matrix. Beneath the composition, Jeakins titled, dated, and signed the impression in graphite.

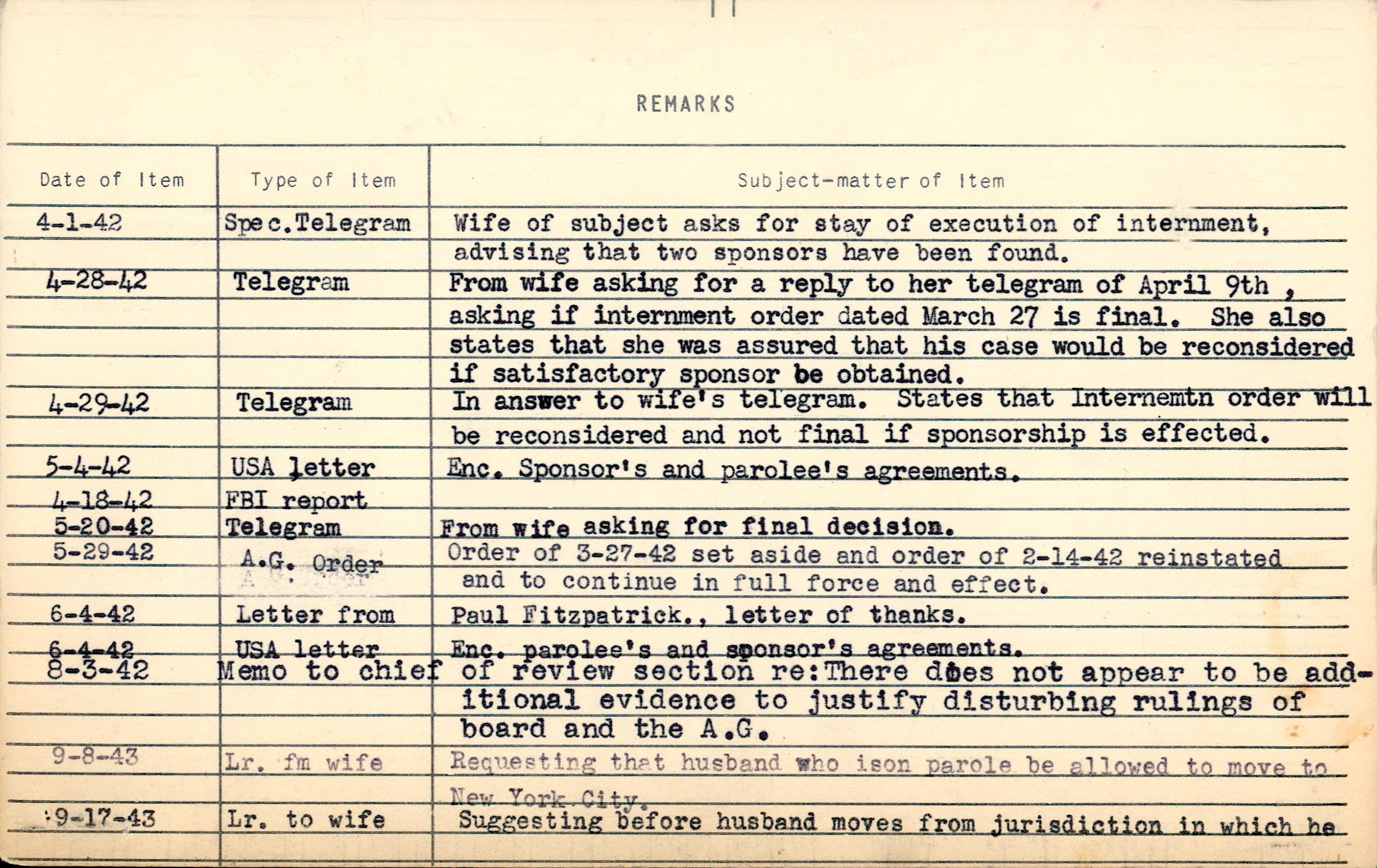

Miscellaneous official-looking marks litter the verso of this print. An intake form is stamped in black ink in the upper right, asking for artist, title, and date received (fig. 2). Filled out in a sweeping cursive that looks nothing like Jeakins’s hand, this form gives the title of the lithograph as “Taro Osato.” The heading at the top of this form, “Federal Art Project,” offers the first indicator that this object is an artifact of a bureaucracy.

The modern term “bureaucracy” first emerged at the end of the eighteenth century as a French pun bemoaning the idea that rule by the people (democracy) or rule by the elite (aristocracy) had been usurped by rule by office furniture, metonymically disparaging the clerks who sat at those bureaus.3 Over the first half of the nineteenth century, the joke spread beyond France, stopped being funny, and became a byword for the mountains of paperwork necessary to sustain not just individual states but the whole capitalist mode of production in which those states were and remain enmeshed.4 The study of bureaucracy in the United States took off in the 1930s and 1940s in tandem with the expansion of the government under Franklin Delano Roosevelt. German sociologist Max Weber’s theory of bureaucracy found an especially eager audience among academics and New Dealers, with his landmark The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism first appearing in English in 1930.5 While he would elaborate on the inevitability of, and his ambivalence toward, bureaucracy in subsequent work, Weber’s metaphor of the iron cage of capitalism first appears here. Puritan asceticism, Weber argues, combined with the “technical and economic conditions of machine production” to imprison not just the working class but everyone employed in a capitalist society.6 The inescapable advance of rationalization through automation that Weber articulates here in terms of the class system informs his model of bureaucracy as a one-way process of mechanization, a definition that held tremendous sway over both bureaucrats and their critics from the New Deal through the end of the twentieth century.

Both the origins of the term bureaucracy and Weber’s formulation of the iron cage speak to an enduring sense that paperwork makes individual office workers into things, parts of the machine. Automation has historically been associated with manufacturing jobs, but the same logic of deskilling animated the management of office work across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. This shift manifested most clearly in increased attention to interactions with paper; commercially produced blank forms proliferated in this period, and optimized writing systems designed for ergonomic efficiency dismantled language into individual, repeatable pen strokes.7 In the case of the form on the verso of Jeakins’s print, the handwriting appears to be Zaner-Bloser script, a twentieth-century adaptation of Spencerian script, the method of business writing that dominated the nineteenth-century educational system in the United States.8 The strategies developed in the nineteenth century endured into and beyond the twentieth century as new technologies made new kinds of work automatable.

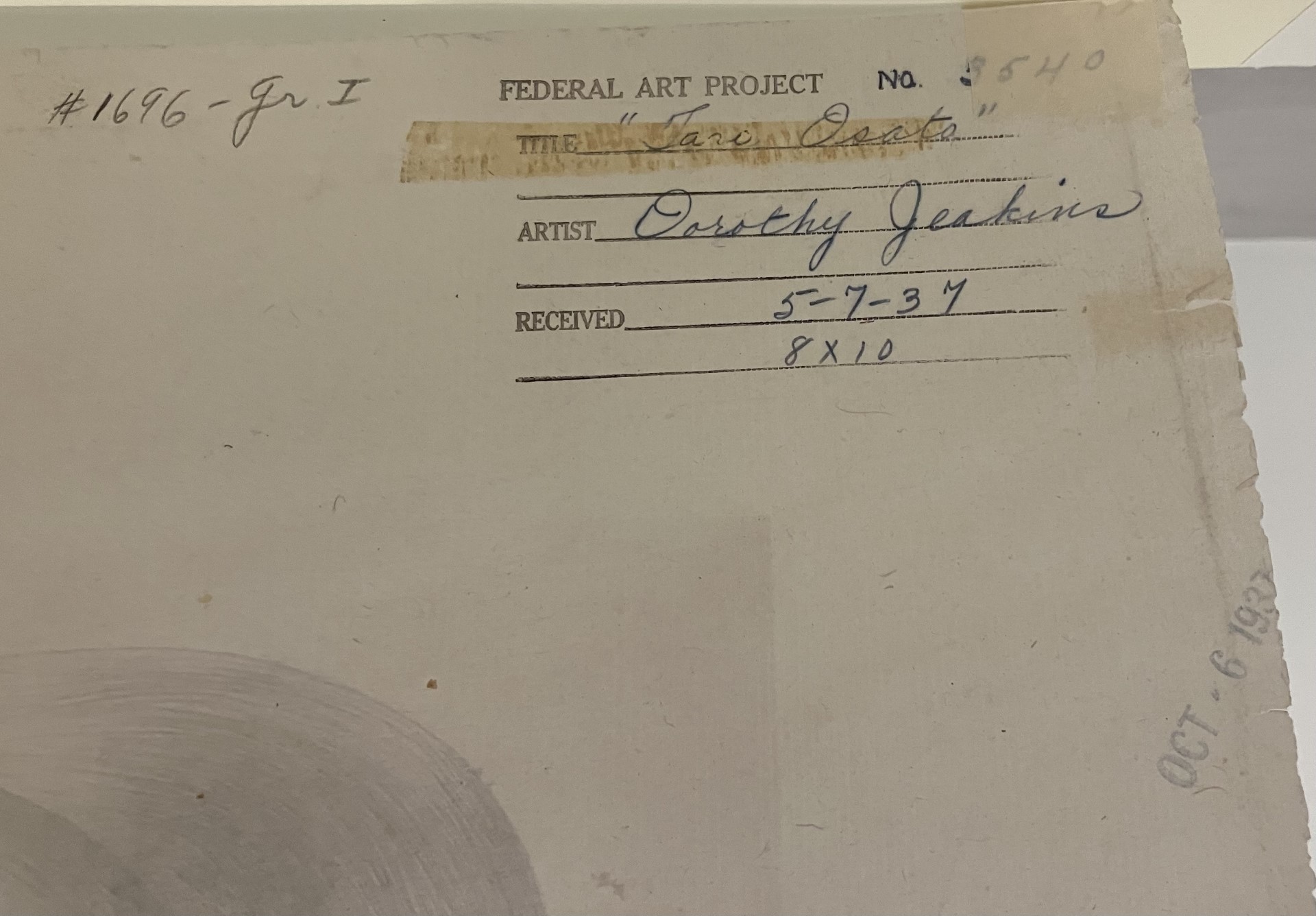

While the act of filling out a document encourages repetition and habit in the clerical worker, a kind of mental stasis, the presence of paperwork is an indicator of circulation—forms demonstrate that something or someone of value has moved through a system, from one place to another.9 The paperwork on the verso of Jeakins’s print testifies not just to movement through space but also to the passage of time. Five months after the receipt date in May, which is itself at least five months after Jeakins made the print, the verso was stamped again “Oct. 6, 1937.” The information on this form, including the title “Taro Osato,” is repeated on a label that was once adhered over this form, leaving behind its residue (fig. 3). Three different kinds of mark making appear on the label card; a commercial printer likely produced the blank form, a WPA clerical worker used a typewriter to fill it in, and another bureaucrat rubber stamped it to mark it with the October date.10 The card captures additional information, the medium, and introduces a new element, an implied threat. The bottom of this form warns the reader: “This work is the property of the United States Government and is loaned subject to the regulations of loan and is not to be removed.”

Paperwork is inextricable from the exercise of power. Individual documents that comprise paperwork derive their authority from the institutions through which they circulate, Lisa Gitelman observes, but those institutions could not function without a steady flow of documents.11 Media theorists define paperwork in terms of the demand it satisfies as a mediator between the public and the state or between different functionaries of the state.12 In art-historical scholarship, documents have long been the terrain of photography historians. In fact, photography’s emergence in the mid-nineteenth century contributed to the development of new regimes of paperwork, as Allan Sekula traces in his study of mugshots and criminology.13 By integrating photographic and photomechanical images into “a bureaucratic-clerical-statistical system of ‘intelligence,’” Sekula finds, French police officials and criminologists sought to make criminality legible through the bodies of the citizenry.14 Invoking the more widely understood sense of “documentary photography,” Robin Kelsey argues that mechanically reproduced images (both prints and photographs) in US government archives serve a doubly documentary function, both recording an event or condition and circulating within a bureaucracy as paperwork.15 Across both Kelsey’s and Sekula’s work, we see bureaucrats gravitate toward photographic and printed images to assert the legibility and legitimacy of paperwork and to bring the outside world under the control of the government office.

The second label related to the lithograph, with its implied “or else,” adds bureaucratic heft to the cataloguing information through its redundant, contractual language and through the format of the form. Where art history assigns immense value to signs of the artist’s hand, particularly inscriptions, bureaucracy prefers the typewritten, the next logical step after standardized handwriting. As the verso of the so-called Taro Osato accumulated layers of progressively dehumanized, perhaps even abstracted, data, it takes on the character of objectivity. Somewhere along the line, seemingly within months of its production, one printed object was conceptually substituted for another, and the label became the point of reference for future cataloguers rather than Jeakins’s print itself. With the stamped date, the typed form, and the regulatory language, the label now bears the formal signs of official status. But it is wrong.

Jeakins produced this print as a federal employee hired to work in the Los Angeles Graphic Arts Workshop of the WPA’s Federal Art Project, a work relief program targeting unemployed culture workers from 1935 to the end of 1942. Like other WPA employees, Project artists were paid weekly wages that varied based on their classification as “unskilled, intermediate, skilled, or professional.”16 Administrators implemented a range of workplace management strategies in an attempt to standardize the creative process: artists were required to clock in and out at their division’s workshop, even if they then worked in their own studios, and quotas were established to encourage productivity.17 Layers of administrative oversight further bureaucratized the process. Printmakers in New York were expected to submit proofs of at least one composition per month to a committee of supervisors, which would determine whether the artist could move forward with an edition—though most were approved, according to Project artist and one-time New York graphic workshop supervisor Jacob Kainen.18 According to Tyrus Wong, who was employed by the Project in Los Angeles at the same time as Jeakins, the artists were asked to submit a matrix for printing every two weeks.19

Printmaking makes the continuity between government art and government paperwork particularly evident. Machine-aided proliferation and circulation are core features of the medium, and collaborations between artists and professional printers have outnumbered artist-printers working in isolation for most of the history of print. In the WPA/FAP Graphic Arts Workshops, professional printers specializing in lithography, intaglio, and relief methods were employed to edition the prints composed by Project artists. Wong recalled two printers in the LA workshop—a young man named Carl Winters, who performed the physically grueling aspects of printing, like lifting the hundred-pound stones, and an older man possibly named “Mr. Nahr.”20 One or both of these men must have executed this lithograph, but their identity, like that of the printer of the form on the work’s verso, is not recorded in the paperwork.21

The artists were not the only ones whom the Federal Art Project sought to discipline through artistic production. In addition to the need for work relief, justifications for the Project often cited the need to cultivate the tastes of the American public and thereby create a market for American art.22 Steeped in the Pragmatist philosophy of John Dewey, WPA/FAP Director Holger Cahill framed this goal in populist terms, as a form of cultural democracy akin to the free art classes offered at WPA/FAP-funded community art centers.23 In order to integrate Project art into daily life, prints, paintings, and sculptures were regularly exhibited to the public in the community art centers and federal and municipal art galleries but also in college libraries, masonic lodges, union halls, and even occasionally in parks and on street corners.24 Regional coordinators attempted innovative exhibition strategies, though concrete data on their efficacy was rarely preserved; one artist-administrator recalled a densely packed “motorized Art Caravan” deployed to tour exhibitions around the mid-Atlantic.25 Press from the period suggests that the fact of the works’ circulation mattered as much if not more than the content of any particular exhibition or object; reviews and announcements tend to linger on quantitative data concerning numbers of objects, visitors, or cities on a tour.26

The works produced by Project artists were supposed to be allocated to schools, libraries, and other public institutions, but these transfers lagged behind the rate at which artists editioned their prints, even after the criteria for eligible institutions was expanded to include museums. Most allocations, including that of the Baltimore Museum of Art, were made during a chaotic four-month period in early 1943 following the official termination of the WPA.27 Despite the best efforts of clerical workers, thousands of artworks were left without an official destination. In one particularly embarrassing episode reported in the press, bales of canvases turned up in a New York junk shop; upon inspection, they were revealed to be the work of prominent artists, including Jackson Pollock.28 Rumors of incinerated work persisted for decades, and employees of the General Services Administration (GSA) are still looking for WPA/FAP works to this day.29

As of this writing, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has directed the GSA’s Public Building Service to dispose of so-called “non-core assets,” which, as currently defined, includes storage and display spaces for not just New Deal art but all art held by or produced through the federal government.30 One published version of the list of these assets includes the Montgomery Bus Station, current home of the Freedom Riders Museum, which transformed the site of a 1961 white supremacist attack on civil rights activists into a memorial to the Freedom Riders’ struggle to integrate interstate bus travel.31 These clear attacks on cultural heritage, and particularly on already marginalized narratives of resistance to the United States’ white supremacist status quo, threaten the GSA’s ability to safeguard the work it has recovered, let alone continue its search for missing art. This change has potentially catastrophic implications for the study of and care for WPA/FAP art, a corpus that captures the confluence of economic crisis, ecological disaster, and antifascist struggle that characterizes both the 1930s and the 2020s.

As the work of government employees, produced and circulated under systematized circumstances and intended to produce a cultured public, Federal Art Project prints like Jeakins’s portrait are both surrounded by layers of bureaucracy and constitute paperwork themselves. They hold a particular status within the canon of the art of the United States by virtue of their association with the Project, the traces of which endure in the many stamps and forms that distinguish these prints from the artists’ production that was not sponsored by the state. With its declaration of property and its implied regulatory threat, the typed label once affixed to the back of Jeakins’s print is clearly paperwork according to Gitelman’s sense of the category—but so is the portrait. Both are printed matter produced by wage workers to fulfil a government need. The doubly documentary status of the print plays out on either side of the sheet: on the recto, the record of a young woman; on the verso, the material residue of the artwork’s office job. As part of a paper machine that kept the Federal Art Project (or the WPA, or even the whole New Deal) operational, this portrait and its miscataloguing invite questions about both the institution and its shortcomings. Something about this art object eluded the system that its circulation as a document sustained.

![Black-and-white lithograph portrait of a man in profile, facing left. He has an aquiline nose , a mustache, and goatee, and a receding hairline. Underneath, in neat script, is written "S MacDonald Wright" on the left, and "Dorothy Jeakins [ill.] 1937"](https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/word-image-19914-4.jpeg)

Setting aside the paperwork that came with the print and returning to the artist’s own inscriptions beneath the image, I sympathized with the generations of cataloguers who defaulted to the neatly typed label. Jeakins’s handwriting is a distinctive blend of cursive and print, of block capitals and lowercase letters. In short, while it is hardly illegible as far as handwriting goes, it does not conform to the system of reading and writing into which office workers have been disciplined since the nineteenth century. There is another contributing factor to the difficult legibility of the artist’s inscription and the object’s miscataloguing: Jeakins learned to read and write in one of the United States’ first Montessori schools—an experimental, self-directed schooling system—before her father “hid” her in “a series of foster homes.”34 The anonymous cataloguer’s Zaner-Bloser script, conversely, was seamlessly assimilated into the WPA/FAP’s bureaucracy—and then later into the museum’s.

The last name Osato was clear enough in the inscription, but I struggled to read the first name. Because I lack the cultural competence to confidently identify Japanese names from ambiguous writing, I sought out a longer sample of Jeakins’s handwriting in the hopes of identifying a pattern.35 Fortunately, the Amon Carter Museum Archives had previously digitized their collection of the photographer Eliot Porter’s papers, including a letter Jeakins wrote to him in the late 1960s in her capacity as Costumes and Textiles Curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.36 By comparing our print’s inscription to the letter, I was able to determine that the sitter’s first name was Teru, not Taro.

Records made available online indicate that Teru Osato was born October 25, 1920, in Omaha, Nebraska. She was the second daughter of Shoji Osato—a photographer born on the island of Hokkaido, Japan—and Frances Fitzpatrick, an aspiring fashion designer and socialite born in Washington, DC.37 Though they lived in Omaha, the couple married in 1919 in Iowa, the closest state to allow marriages between Asian and white people at the time.38 Frances likely forfeited her US citizenship through this act.39

Teru’s sister provided the first key to reuniting the lithograph and its subject. Older than Teru by a year, Sono Osato first gained fame as a teenager as the youngest—and only Asian American—dancer in the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, touring Europe and the United States for several years. From Sono’s memoir, Distant Dances, I learned that around 1936, Frances, Teru, and younger brother Tim were living in the Los Angeles area while Frances pursued her own professional ambitions.40 The Omaha Morning Bee-News supplied more details: Teru had been enrolled in a private school in Los Angeles, Tim would attend as well, and Frances had spent the summer running a teahouse with Shoji in Chicago, in buildings once used for the World’s Columbian Exhibition and furnished by the Japanese government.41 Teru would have been at most sixteen years old when Jeakins depicted her. Because her mother was a feature of Omaha high society and her sister became famous early as a ballet dancer, traces of Teru’s childhood persist. Had that not been the case, I may never have found her.

A few years after Jeakins’s portrait entered the WPA/FAP system, Teru Osato enrolled in Bennington School of the Arts (now Bennington College) (fig. 5). She studied theatrical design with an emphasis on lighting and took dance classes with renowned choreographer Martha Graham.42 As an upperclassman, her field courses took her to work in New York.43 She designed the lighting for and performed in an evening of dance and music sponsored by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association Dance Center, sharing the bill with both Martha Graham Company dancers and Woody Guthrie.44 She lived with her sister, who had left the Ballets Russes for the American Ballet Theatre. In 1943, the year that the Baltimore Museum of Art’s impression of “Taro Osato” arrived at the museum with more than nine hundred other prints, the New York Daily News announced Teru Osato’s upcoming marriage to Naval Lieutenant Vincent Meier.45

The first factor contributing to the persistence of the cataloguing error is biographical: Teru Osato Meier died on October 24, 1946, of rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare and aggressive soft-tissue cancer. It was the day before her twenty-sixth birthday.46 The last document to index her life, her death certificate, preserves detailed information concerning her birth and her death, her parents and her spouse, her sex and her “color or race.” The certificate was filed under her married name, a naturalized form of obfuscation that primarily impacts women. Despite her budding theatrical career, her profession is given as “Housewife.” Ironically, Dorothy Jeakins went on to considerable renown in the same industry Teru had just begun to enter. Following her own wartime marriage and its subsequent end, Jeakins drew for Walt Disney Studios before breaking into costume design, the field in which she would become celebrated.47

Not long after the portrait was submitted, bureaucratic error intervened between Jeakins’s object and subsequent viewers, replacing “Teru” with “Taro” and effectively separating this young woman from her own image. Some of this institutional failure can be attributed to the sheer volume of prints that the WPA clerks were expected to account for, first in the regional and then in the national distribution centers. It is estimated that, over the course of the Federal Art Project, printmakers produced at least 240,000 prints pulled from 11,300 matrices, all of which needed to be catalogued.48 Much of that labor was compressed into the four-month allocation window at the conclusion of the FAP. Sexism and racism must also contribute to the explanation—given the constant flow of works to be processed, how much attention would be spared to read the handwriting on a print by a young woman of a young woman, especially one with a “difficult” name?

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, a US government record of a Japanese name was not a neutral object. In the anti-Japanese backlash to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Sono was barred from international tours with the American Ballet Theater and then barred from West Coast travel, changing her career path. Though this would ultimately lead her to success on Broadway, including starring in the role of Ivy Smith in On the Town (1944), she found herself pigeonholed in “exotic” roles, a designation that became tantamount to “suspicious” as Japan’s occupation of China progressed.49 Another two-page spread in the New York Daily News speaks to the conditional status of the Osato family’s American identities. Headlined “She’s Irish-French-Japanese—and a Hit!,” the story hinges on Sono’s role as lead dancer in One Touch of Venus (1943) but profiles the whole Osato family, swinging back and forth between casting each as exotic and stressing their American credentials.50 “In spite of her features and her name,” the reader is assured, Sono “thinks and talks American.” Teru is photographed wearing a kimono and holding a teapot while at work in the family tea house, but her engagement to the “American naval lieutenant” is mentioned three times in two pages. The intensity with which the author insists that “there is no question about the patriotism of the Osatos” suggests, paradoxically, that she may in fact have had her doubts or assumed that her readers would.

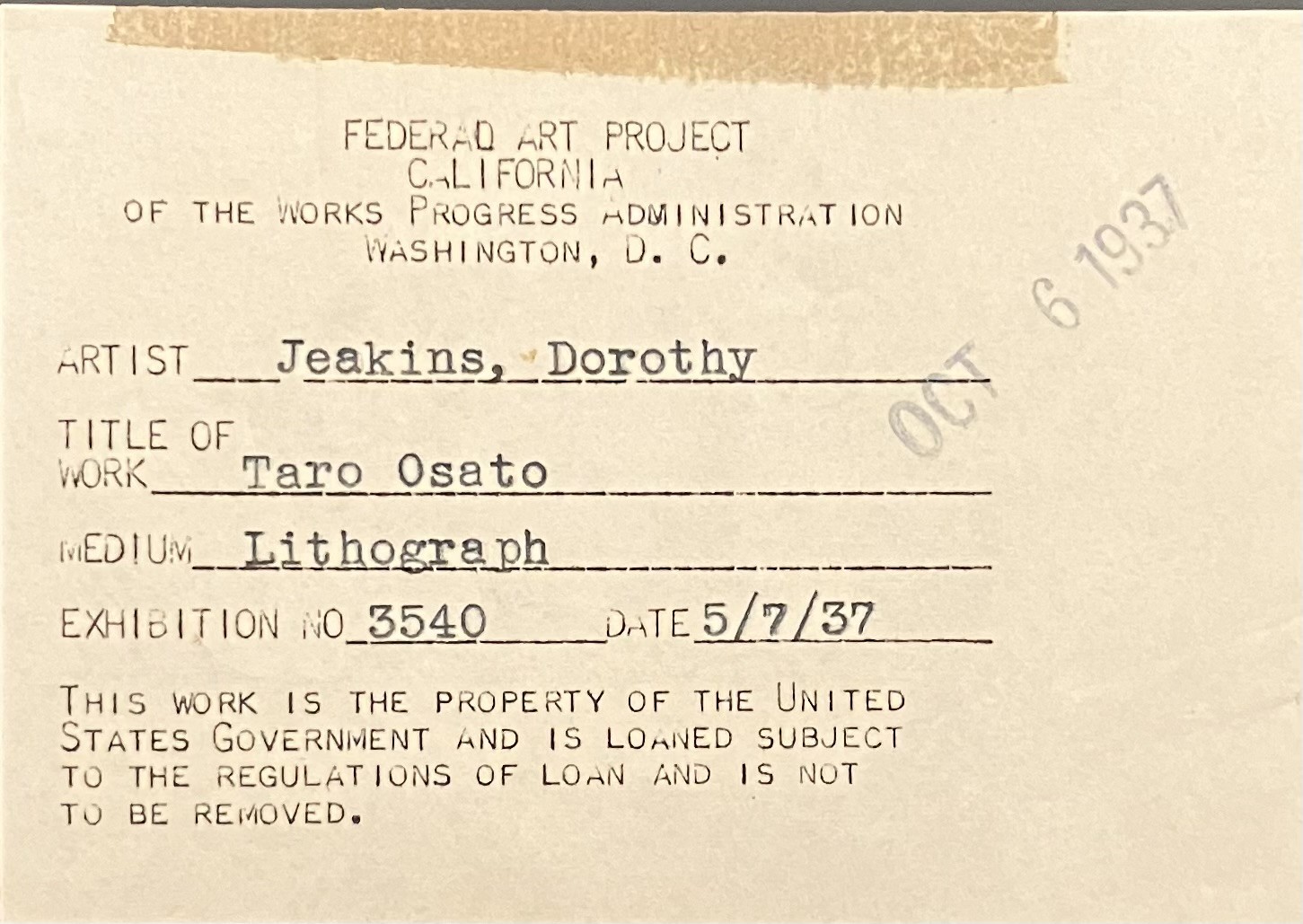

Jeakins’s portrait of Teru and its attendant paperwork must be understood alongside another document produced by federal employees (fig. 6): an Internee Card in the National Archives indexing Shoji Osato’s detention on the South Side of Chicago. Though Chicago was outside the West Coast zone within which the US government interned 120,000 people of Japanese descent, Shoji was arrested in December 1941.51 As a longtime member of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society in Chicago and an agent of the Japan Travel Bureau, a Japanese government agency, he was regarded as a threat to national security despite decades living in the United States.52 Though his connections to Japan were ultimately deemed to be personal and commercial rather than military, he was considered an ”enemy alien,” a designation that would have ramifications for the rest of the Osato family.53 On the recto, this card records Shoji’s name and address; his apprehension, hearing, and parole dates; and the names of the various bureaucrats and offices who took custody of both him and his paperwork. The verso offers a timeline of correspondence related to the case. Spilling onto a second card, this record of telegrams, letters, and phone calls is a testament to the persistence of Frances Fitzpatrick Osato, referred to here as “wife of subject.”54 Though he was paroled in the summer of 1942, after six months of detention, the dates on the card demonstrate that Shoji remained under surveillance and unable to leave Chicago for years afterward.

Between Teru’s portrait, Sono’s press coverage, and Shoji’s internment record, the Osato family’s documentation demonstrates that visibility was not a guarantee of legibility or safety. Shoji’s internee card and Teru’s portrait bear many of the same kinds of marks, with signatures, dates, and stamps indexing each document’s movements over time through a labyrinthine bureaucracy. In isolation, the bureaucratic slippage that turned Teru into Taro might be best understood as a case of negligence born of ignorance with largely art-historical consequences. It would be reasonable to dismiss this emphasis on a mistranscribed name as overblown. But the same federal government that mistranscribed Teru’s name in its paperwork also relied on its bureaucratic apparatus to determine whether or not her father was a threat to the state. Though the production contexts of the two documents differ dramatically, as do their implications for their subjects’ freedom, Teru’s paperwork is haunted by her father’s.

There is no single person to hold responsible for the slip of a pen that removed Teru from the art-historical record; authorship of the surrounding paperwork has been obfuscated and distributed by the mechanizing effect of bureaucracy. Just as the Project art was allocated haphazardly, administrative records were retained inconsistently, completely dependent on the whims of regional administrators and their clerical workers.55 According to New Deal Art Program historian Richard McKinzie, rather than create a single coherent filing system, the typists assigned to the FAP may have been encouraged to seed the Project’s files with multiple copies of the same document in different locations to increase the odds of a user stumbling across the information they needed.56 When the Project folded and workers were laid off, reference volumes and tranches of documents reportedly went missing. Redundancies abound in the archives as a result, as do maddening lacunae—such as the absence of any definitive list of sites or institutions that received allotments of art.

The gaps, erasures, and missed connections bred by careless paperwork have consequences for scholarship. In the eighty years between the allocation of Jeakins’s print to the Baltimore Museum of Art and its exhibition in Art/Work: Women Printmakers of the WPA, Teru Osato was never put on view, even when other lesser-known works from the museum’s allocation were exhibited. Incorrect cataloguing data made this object a dead end for scholarly research and difficult to fit into any curatorial vision. When this print arrived at the BMA in 1943, the museum had recently added theater and dance to its definition of “art” for collecting purposes—fertile ground for a portrait of a Martha Graham–trained dancer and designer whose sister was a Broadway sensation at that very moment.57 However, Teru Osato’s role in vibrant Asian American artistic circles on both coasts remains underexplored. Careless paperwork, even when produced without malice, ensures that the xenophobia of the past continues to shape the canon of American art.

Taking the slippage between government art and government paperwork seriously opens up new approaches to the study of WPA/FAP prints. In the case of Teru Osato, a discrepancy between the artist’s inscription on the recto of a print and the bureaucrat’s form on that same print’s verso offers a glimpse of the ways that power is instantiated through the circulation of printed matter. This print and works like it should be studied not just in the wider artistic context of the 1930s but also alongside other documentary manifestations of the New Deal bureaucratic state. Looking at the recto and not the verso is to only see half the object. Strategies already developed by photography theorists like Sekula and Kelsey reveal how power operates in and through government art. Even the bewildering state of the WPA/FAP archives could be understood not as a distraction from a real subject located elsewhere but as part of the object of research itself. Paperwork can be opaque and frustrating, signifying less than the sum of its parts—often, as David Graeber notes, because its real purpose is to mediate the violence from which the state derives its authority.58 That violence is on the surface of documents like internment records but is latent in all state paperwork. As an especially formally and theoretically complex variety of paperwork, the WPA/FAP print makes it easier to see the interplay of individual intention and systemic power that make up all bureaucracies.

Cite this article: Robin Owen Joyce, “Paperwork: Bureaucracy and Legibility in a WPA Portrait,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19914.

Notes

I am grateful to Virginia Anderson and Andaleeb Banta for their support of this project and their comments on drafts of this note. An earlier version of this article was presented through the 2024 BMA Scholars Lecture Series. The fellowship at the Baltimore Museum of Art that made this research possible was supported by the Getty Paper Project.

- A small selection of WPA/FAP works was exhibited in October 1943 as Cross Section of America, followed by an exhibition in the 1980s and another in 2000. See “Cross Section of America,” Baltimore Museum of Art News 6, no. 1 (1943): 4; and Sarah Dansberger, “Baltimore Museum of Art Exhibitions (1923–2022),” Library Catalogue, Baltimore Museum of Art, last updated January 16, 2024, https://library.artbma.org/client/en_US/bma. ↵

- The exhibition ran from November 5, 2023, to June 30, 2024. This project benefited from the early curatorial and conceptual work of Andaleeb Banta, Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings, National Gallery of Art. ↵

- Ben Kafka, The Demon of Writing: Powers and Failures of Paperwork (Princeton University Press, 2012), 78. ↵

- Michael Zakim, “Paperwork,” Raritan 33, no. 4 (2014): 46. ↵

- Lawrence A. Scaff, Max Weber in America (Princeton University Press, 2011), 201–2. ↵

- Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (1904; Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), 181. ↵

- Lisa Gitelman, Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents (Duke University Press, 2014), 31. ↵

- Zakim, “Paperwork,” 44–45. ↵

- Gitelman, Paper Knowledge, 22. ↵

- On the rise of commercial printers over the course of the nineteenth century and their role in the growth of bureaucratic systems, see Gitelman, Paper Knowledge, 21–52. ↵

- Gitelman, Paper Knowledge, 5. ↵

- Kafka, Demon of Writing, 10. ↵

- Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” in The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, ed. Richard Bolton (MIT Press, 1992), 342–89. ↵

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 351. ↵

- Robin Kelsey, Archive Style: Photographs and Illustrations for US Surveys, 1850–1890 (University of California Press, 2007). ↵

- Richard McKinzie, The New Deal for Artists (Princeton University Press, 1973), 85. ↵

- Jacob Kainen, “The Graphic Arts Division of the WPA Federal Art Project,” in The New Deal Art Projects: An Anthology of Memoirs, ed. Francis V. O’Connor (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972), 162–63. ↵

- Kainen, “Graphic Arts Division of the WPA Federal Art Project,” 160. ↵

- Oral history interview with Tyrus Wong, January 30, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (hereafter AAA). ↵

- Oral history interview with Tyrus Wong, January 30, 1965. ↵

- WPA/FAP printers did not employ chops, the marks professional printers use to distinguish editions printed at their press. ↵

- See Victoria Grieve, The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009). ↵

- Holger Cahill, foreword to Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, ed. Francis V. O’Connor (New York Graphic Society, 1973), 33–44. On the origins and features of cultural democracy, see Andrew Hemingway, “Cultural Democracy by Default: The Politics of the New Deal Arts Programs,” Oxford Art Journal 30, no. 2 (2007): 269–87; and Jane De Hart Mathews, “Arts and the People: The New Deal Quest for a Cultural Democracy,” Journal of American History 62, no. 2 (1975): 316–39. ↵

- To my knowledge, no single authoritative list of WPA/FAP exhibitions survives, but individual state administrators retained different forms of records, some more complete than others. Photographs of New York City exhibitions in the kinds of locations listed above are held in the Archives of American Art. See Federal Art Project, Photographic Division collection, ca. 1920–65, bulk 1935–42, box 26, folders 10–19, and box 27, folders 1–10, AAA. ↵

- Eugene Ludins, “Art Comes to the People,” in Art for the Millions, ed. Francis V. O’Connor, 2nd ed. (New York Graphic Society, 1975), 232. ↵

- “Unemployed Arts,” Fortune 15, no. 5 (1937): 108–17, 168–75. ↵

- McKinzie, New Deal for Artists, 123. ↵

- McKinzie, New Deal for Artists, 124. ↵

- On incinerated works, see W. E. W., “The New Deal and the Arts” {Report}, Archives of American Art Journal 4, no. 1 (1964): 2. ↵

- “Statement regarding GSA’s disposal of non-core assets,” US General Services Administration, last updated March 4, 2025, https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/newsroom/news-releases/statement-regarding-gsas-disposal-of-noncore-assets-03042025. ↵

- Josh Moon, “Historic Montgomery Bus Station, Freedom Riders Museum Part of DOGE-Ordered Sell-Off,” Alabama Political Reporter, March 6, 2025, https://www.alreporter.com/2025/03/06/historic-montgomery-bus-station-freedom-riders-museum-part-of-doge-ordered-sell-off. ↵

- Oral History interview with Dorothy Jeakins, June 19, 1964, AAA. ↵

- Oral History interview with Stanton MacDonald-Wright, April 13–September 16, 1964, AAA. The nickname evidently came from Time magazine. ↵

- Oral History interview with Dorothy Jeakins. On her father, see Lawrence Van Gelder, “Dorothy Jeakins Dies at 81; Designed Costumes for Films,” New York Times, November 30, 1995, A18. ↵

- I suspect that previous cataloguers—both WPA/FAP employees and subsequent Baltimore Museum of Art employees—also lacked this competency, contributing to the error’s persistence. ↵

- Dorothy Jeakins to Eliot Porter, February 6, c. 1967–70, Eliot Porter Papers, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Archives, Fort Worth, TX. ↵

- Teru Osato Meier, death certificate, October 24, 1946, no. 0020514, Historical Vital Records Collection, New York City Municipal Archives. ↵

- Sono Osato, Distant Dances (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), 5. ↵

- Carol J. Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War (Oxford University Press, 2014), 121. ↵

- Osato, Distant Dances, 123. ↵

- “Miss Osato Returns,” Omaha Morning Bee-News, October 21, 1936, 11. ↵

- “Teru Osato’s Daily Schedule for the Bennington School of the Arts,” 1941, Bennington School of the Arts, 1940–42, Bennington College Archive, Bennington, VT, http://hdl.handle.net/11209/17163. ↵

- “Omahans Return to Bennington from Field Course Jobs in New York City,” Evening World Herald (Omaha, NE), February 25, 1941, 14. ↵

- The Dance Observer Presents: Jane Dudley, Sophie Maslow, and William Bales (program), May 3, 1942, Bennington School of the Arts, 1940–42, Bennington College Archive, Bennington, VT, http://hdl.handle.net/11209/9033. ↵

- Danton Walker, “Broadway,” New York Daily News, December 13, 1943, 32. ↵

- Teru Osato Meier, death certificate. ↵

- Oral history interview with Dorothy Jeakins. Jeakins was a cowinner of the first-ever academy award for costume design for her work on Joan of Arc (1948), the start of a long and illustrious career designing for stage and screen. ↵

- This total number of prints comes from McKinzie, New Deal for Artists, 105. The total number of matrices appears in Final Report on the WPA Program, 1935–1943 (US Government Printing Office, 1947), 65. ↵

- Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway, 129. ↵

- Ruth Reynolds, “She’s Irish-French-Japanese—and a Hit!” New York Daily News, January 16, 1944, 56–57. ↵

- Osato, Distant Dances, 198. On the number and region of detainees, see Mae M. Ngai, “‘An Ironic Testimony to the Value of American Democracy’: Assimilation and the World War II Internment of Japanese Americans,” in Contested Democracy: Freedom, Race, and Power in American History, ed. Manisha Sinha and Penny Von Eschen (Columbia University Press, 2007), 237. ↵

- Takako Day, “The Japanese Mutual Aid Society and Charles Yasuma Yamazaki,” Discover Nikkei: A Project of the Japanese American National Museum,” June 18, 2019, https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2019/6/18/mutual-aid-society-1/. ↵

- Oja, Bernstein Meets Broadway, 132. ↵

- Shoji Osato, INS card, file no. 146-13-2-23-78, General Records of the Department of Justice WWII Alien Enemy Internment Case Files 1941–1951, RG 60, box 255, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD. Online version available through the Archival Research Catalogue (National Archives Identifier 1094212), accessed November 3, 2024, at www.archives.gov. ↵

- McKinzie, New Deal for Artists, 194. ↵

- McKinzie, New Deal for Artists, 194. ↵

- Kent Robert Greenfield, The Museum: Its First Half Century (Baltimore Museum of Art, 1966), 37. ↵

- David Graeber, The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy (Melville House, 2015), 57. ↵

About the Author(s): Robin Owen Joyce is the Assistant Curator of Academic Engagement at the Baltimore Museum of Art.