Post Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980–2016

Curated by: Faheem Majeed

Exhibition schedule: Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, Chicago, July 15, 2016–January 8, 2017

Exhibition catalogue: Faheem Majeed, Post Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980–2016, exh. cat. Chicago: Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, 2017. 36 pp.; 25 color illus. $10.00

Artist Faheem Majeed curated the exhibition Post Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980–2016 for Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, which consists of 110 objects by modern and contemporary African American artists who have had no academic training. Categories such as “folk,” “intuitive,” and “outsider” art have historically filled the lack at the heart of this qualification, yet they have done little to illuminate the worlds of meaning that have informed such heterogeneous styles and formal inventiveness exemplified by the drawings, paintings, sculpture, assemblage, wood carvings, and decidedly handmade objects that have come to define the field. Majeed, whose own studio practice extends into cultural activism and art administration, inquires after the relevance of these terms by looking back at their sources. What social and cultural positions do these terms presume? How do they exclude? To what boundaries does the term “outsider” refer? Exploring these questions is the hefty task of this compact show Majeed has organized.

As the title implies, the exhibition refers to an earlier event, namely Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980, organized by Jane Livingston and John Beardsley for the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1982. Regarded as one of the watershed events in the history of African American twentieth-century folk, self-taught, and outsider art, the Corcoran exhibition validated art of non-academically trained African Americans within the art mainstream and, unsurprisingly, galvanized the market for the artwork of these individuals. With a checklist nearly four times that of the Intuit installation, as well as a nationwide tour, the original exhibition introduced and defined a new field of art that was not conventionally traditional, nor utilitarian, but “generally untutored yet masterfully adept.”1 Black Folk Art in America was indisputably pioneering, yet ultimately problematic in the ways it flirted with primitivist stereotypes that figured the self-taught black artist as uneducated and impoverished. In subsequent decades, the project instigated critical debates over definitions of folk art, artistic value, and authenticity; the relationship between academically trained African American and black folk artists; and the framing of such marginalized artists within the artistic mainstream.

The Corcoran installation was arranged by artist, whereas in the two main galleries, the Intuit exhibition presents works by artists from the original 1982 show that are intermingled with objects by contemporary African American artists whose aesthetics or biography resonate with those of the earlier generation. Because no thematic texts or additional didactics are included, visitors are compelled to navigate through the dense array of objects, using only the biographical information on labels provided for each artist. For those attempting to discern a line of continuity, the experience can feel laborious at times, yet the challenge is instructive. Before assuming relationships between older and contemporary artists based purely on visual similarities (about seventy percent of the checklist consists of work by the earlier generation), visitors must reconcile their assumptions with the particularities of each artist history, practice, and sociocultural experience. In a field where the labels of “outsider” and “folk” are wielded by those intent on categorizing works in terms of marginality, difference, or deficiency, this exhibition shifts the interpretative frames back to the artists themselves and destabilizes the ways in which such labels circumscribe meaning.

Taking his cue from Glenn Ligon and Thelma Golden’s 2001 exploratory concept of “post-Black”—a term describing artists adamantly against being labeled “black artists” so that they might explore a multiplicity of ideas concerning racial blackness—Majeed engages these questions around folk and outsider by adopting a similar non-essentialist and inquisitive stance in Post Black Folk Art in America. He is therefore unconcerned with reaffirming categories or defending labels of what counts as black folk art and its cognate, outsider art. Instead, his curatorial approach highlights the challenge of artistic self-determination within a cultural terrain shaped by inherited terms, such as “outsider,” which belie such diverse practices. In reading the object labels, for instance, shared circumstances informing the artists’ creative processes emerge, such as histories of personal and cultural trauma, incarceration, migration, poverty, religious belief, or cultivation of artistic skill through unconventional occupations. Yet as viewers, are we to accept these circumstances as affirmations of outsiderness? Majeed’s approach at Intuit suggests not, and the result is an exhibition that neither sensationalizes difference nor offers straightforward answers. Instead, it aims “to understand connections, motivations, and ultimately outcomes” engendered by institutions of outsider art.2

A related point of departure for Majeed’s institutional critique is a significant, though little publicized, intention of Black Folk Art in America. As visitors learn from the opening panel, the 1982 show was motivated in part by the desire to attract the black community to the Corcoran Gallery and catalyze a conversation about museum diversity and the institutional marginalization of black artists. These issues also frame Post Black Folk Art in America and bring attention to Intuit’s majority white stakeholders who have constituted its primary audience. On the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of its founding, in a move that honors its role in exhibiting, collecting, and advocating for artists outside of the mainstream, the exhibition calls Intuit to task by reflecting on definitions of outsider art and the public that the institution seeks to serve.

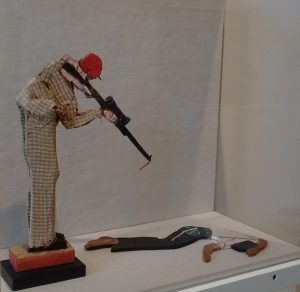

Two works of art at the entrance to the exhibition signify both the specificity and capaciousness intrinsic to the unusual history of black folk art. Steven Ashby’s Untitled (Hunter and Victim) (nd; collection of Robert A. Roth, Chicago) makes clear Majeed’s intention to connect the art to contemporary audiences living in the era of Black Lives Matter (fig. 1). Ashby’s work calls upon the stance of the movement against anti-black, state-inflicted killings. The blunt figural arrangement not only shows the act of gunshots causing human lives to flatline, but also the narrow dimensions of the wooden board figures suggest that social attitudes just as readily level the lives of others. Thornton Dial’s Royal Flag (1997–98; collection of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta, GA), by contrast, pulsates (fig. 2). A large composition, its surface crinkles with cinched, twisted, and knotted fabric. Some colors are stitched together, while others are brushed-on and worked-in paint that has dried over assorted found objects. The stiffened array of patterns is difficult to see up close; one needs the wider view to perceive Dial’s ability to unify cast off objects with his elevating, creative touch. As visitors to Majeed’s show, we similarly require a broad view to understand how Post Black Folk Art canvases this spectrum between the particular and the public.

the right, along with artworks by Mose Tolliver, Steven Ashby, Juanita Rogers, Clementine Hunter, and Sister Gertrude Morgan, courtesy of the author.

Fifteen objects from the 1982 show appear in the first and largest gallery. These works meet the aim of the retrospective exhibition, and many still are compelling today. These include a trio of Joseph Yoakum’s transporting, abstract landscapes, Sister Gertrude Morgan’s evangelical paintings, a set of William Dawson’s wide-eyed, figural wood carvings, and an assemblage of a cat head by Ashby. Other artists original to Black Folk Art in America are represented by objects not shown in the earlier show but exemplify their bodies of work. William Edmondson’s delicate handling of limestone appears in Angel (nd; collection of Robert A. Roth, Chicago), in which the curvaceous figure emerges out from the rough, chiseled areas of the angel hair and wings. Such textural contrasts smooth as they heighten the gentleness of what might otherwise lean towards hieratic severity. One gets a similar sensation from Two Doves (nd; collection of Lael and Eugenie Johnson, Chicago), whose downcast heads and blocky perch recall Edmondson’s work as a gravestone carver for his Nashville community. Two painted metal cutouts by David Butler, Horse and Rider and Mermaid (both 1983, David Csicsko/David Syrek collection, Chicago), delight with their spunky lines and vibrant dotting. With their whimsical shadows against the white walls of the gallery, they convey the fantastical aspect of Butler’s practice, along with an elephant whirligig installed below demonstrates his homegrown inventiveness. When closely viewing objects, such as Jesse Aaron’s wood animals (conjured with the most economical of means from found wood or roots, glass eyes, and cut metal) or Nellie Mae Rowe’s bubblegum sculpture, what Livingston identified as the primal “crudeness” of black folk art appears less pejoratively as experimentation with form and materials on hand.

In an interview with Majeed, published in the exhibition catalogue, Black Folk Art in America, which focused on artists working from 1930 to 1980, Livingston admits that only a portion of this generation of African American self-taught artists were represented. Fortunately, several more are included at the Intuit show and offer a fuller picture of the field at the time of Corcoran Gallery show. For example, the omission of Minnie Evans in the 1982 exhibition is corrected by the inclusion at Intuit of an untitled work (1967; collection of Cleo F. Wilson, Chicago). The example displays the reach of Evans’s visionary practice and resonates with that of Yoakum, Morgan, and David Philpot. Here, her signature vegetal motifs unfold into a pastoral psychedelia of curling arabesques and butterflies from which smiling faces and eyes peer. Especially striking are the upper portions, where the designs have been pasted onto the canvas, as well as a series of numbers on the lower right. The numbers are likely dates, suggesting that she revised the picture over a period of twenty years. This work shows artistic intentionality and process that critical responses from the 1980s neglected, and which new archival research is recovering. Caring for an Elderly Man by Clementine Hunter (c. late 1960s; collection of Scott H. Lang, Chicago) hangs in a corner with drawings by Nellie Mae Rowe and Juanita Rogers, two Southern women artists from the 1982 exhibition. In their company, Hunter’s genre scene introduces a nostalgic domesticity that the other Surrealistic compositions resist. By extension, the inclusion of Hunter draws out a contrasting formal aesthetic that dominated the Corcoran exhibition, namely an “uninhibitedly prolific” and “bold” style represented by the expressive brushwork of William Hawkins, Sam Doyle, and Mary T. Smith—as well as Bill Traylor’s pictographic drawings—all on view at Intuit.

In practice, black folk art has always had broader appeal and was thought accessible precisely because it could speak to social and cultural connections. The addition of more recent art in the Intuit exhibition is positioned within this gap, and object labels insist on bringing our attention to the culturally specific circumstances in which the art was made. Among the most affecting works is Arkee Chaney’s ceramic sculpture, Governmental Premeditated Murder (2012; Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project, Chicago), where a black man is bound in an electric chair, the head and chin straps pitching his face upward. The man is slight, and his feet hang above the floor. The glazing of the sculpture both freezes him and rivets our gaze to this moment of death, an event possibly observed while Chaney served his own prison sentence. Locality serves as the frame for Herbert Singleton’s carved wooden reliefs that draw upon New Orleans, and its black mourning and spiritual practices, and Chicagoan Eddie Harris’s wood construction that channels Black Power and that reimagines Batman as a totem for resistance. Philpot’s abiding interest in African forms appears in hand-carved wooden staffs and a stunning beaded stool adorned with rhinestones and cowry shells. For Tracy Crump, drawings functioned as a diary as she struggled through an abusive relationship. In Ramalt, the example included at Intuit (c. 2000; collection of Cleo F. Wilson, Chicago), female bodies serve as flourishes and flourish within a composition that resonates with the work of Minnie Evans from nearly four decades earlier. With the addition of these artists arises the common story of individuals who are not condemned by their circumstances but have their art and careers formed by them.

In the thirty-five years since Black Folk Art in America, self-taught art can be unapologetically discussed within the frame of human stories that wend their way in and out of the art world. Put another way, the interaction of self-taught artists with the art world is readily acknowledged, not denied. This reciprocity is glimpsed in two loans from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation of Atlanta, Georgia. For example, without foundation intervention, Martha Jane Pettway’s denim and corduroy quilt from the 1940s (William S. Arnett Collection of Souls Grown Deep Foundation) might not have been preserved, nor would subsequent generations of the Gee’s Bend community in Alabama, from which Pettway hails, have likely continued to engage in art-making.

The aquatint of a quilt pattern by Louisiana P. Bendolph (2005; collection of William S. Arnett) is part of Bendolph’s ongoing engagement with her mother’s quilting practice, a turn instigated by seeing her mother’s quilts on display in a 2002 exhibition in Houston organized by the Souls Grown Deep Foundation (fig. 3). Its founder, William Arnett, has also served as an advocate for Ronald Lockett and Lonnie Holley, whose works are displayed in the second gallery. Due in large part to Arnett’s initiatives, Lockett and Holley now have their place in major museum collections, and a spate of important exhibition and archival materials, and other published resources, are available (some through the foundation website) that form the basis for future scholarship and criticism and secure knowledge of the contributions and productions of these artists.

Majeed’s essay and interviews in the slim exhibition catalogue bring together perspectives that illuminate several dimensions of the Corcoran Gallery show, including its curatorial origins, place within a broader history of modernism, and problematic use of the term “folk” that gained traction in the aftermath of the exhibition. The interview with one of the founders of Intuit, Cleo Wilson, also makes clear the reason why Intuit was an obvious choice for organizing this anniversary event. The founding of Intuit directly resulted from the appearance of Black Folk Art in America at the Field Museum of Natural History, in Chicago—which is notably not an art museum. For the lack of a community, much less an institutional gathering place, for those interested in self-taught art, a group of Chicago gallerists and collectors founded Intuit in 1991. Post Black Folk Art affirms the importance of the city within the history of self-taught and outsider art as an embrace of all creative practices.

Moreover, the cultural significance of the exhibition is important in another, more oblique way: by inviting Majeed as guest curator, Intuit also acknowledges the historical current of socially engaged practice carried out in Chicago. Theaster Gates may be its most visible practitioner, but crucially, socially engaged practice in Chicago has deep roots reaching back to the 1940s. The primary aim of the South Side Community Art Center, where Majeed formerly served as executive director, was to offer support for the self-determination of local artists and “to convert their passion into a career,” where no infrastructure for learning, exhibiting, and patronage formerly existed.3 As David Ross, the first assistant director of the SSCAC phrased it to Eleanor Roosevelt at the dedication of the center in 1941: “Thus it was that the golden opportunity for the development of the young Negro artist, hard up for food, materials and schooling, came with the Federal Arts Projects. Here was our chance to stop shining shoes all week and painting only on Sundays. This gave us a means of learning as well as earning our living as artists.”4 The first generation of black folk artists did not necessarily have these resources, and their lives show how creative work can thrive with minimal access to it. From the perspective of socially-engaged practice, the pressing question assumes an ethical cast: how can their stories and art instruct a new generation of artists and their supporters?

Directing support to artists across social difference in economic disparities, while recognizing and enabling creative self-determination, is the call launched by Post Black Folk Art in America, and these commitments will require the same exploratory spirit that energized audience encounters with black folk art in the first place. That such dedication was directed outside of the mainstream art world also suggests that the way forward depends upon including and fostering relationships with new audiences. The ways this art evades simple explanation has always indicated that it could speak from artists’ locales, across art histories, and to diverse contexts. Several exhibitions in recent years have revealed this polycentrality. (5) Post Black Folk Art makes this turn official in name and local in scale: Chicago’s histories of community art activism and its wide embrace of aesthetic sensibilities are conjoined, uniting two histories that perhaps were never really separate, save for the blindness of the art world in ways that are now—in promising ways—being corrected.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1601

PDF: Yau Review of Post Black Folk Art in America

Notes

- Jane Livingston, “What It Is,” in Jane Livingston and John Beardsley, with Regenia Perry, Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980, exh. cat. (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi and the Center for the Study of Southern Culture in association with the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1982), 11. 2. Faheem Majeed, “Artist Statement,” http://www.faheemmajeed.com/copy-of-about ↵

- Faheem Majeed, “An Outsider to Outsider or Post Folk or Black Folk Art Ain’t Folk Art Made by Black Folks,” Post Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980–2016, exh. cat. (Chicago: Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, 2016), 8. ↵

- Quoted in Margaret Goss Burroughs, “Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center: A Personal Recollection (1987), http://iwa.bradley.edu/ChicagoCommunityArtCenter ↵

- For example, Maurice Tuchman and Carol S. Eliel, Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992), Thomas J. Lax and Elizabeth Gwinn, When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South, exh. cat. (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 2014), and Lynne Cooke, Outliers and American Vanguard Art, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, forthcoming 2018). ↵

About the Author(s): Elaine Y. Yau is Adjunct Professor in the Department of Art and Design, Azusa Pacific University.