Problem Portraits: Francisco Oller in the Age of US Imperialism

In the years following the War of 1898 and the US invasion and seizure of Puerto Rico, local artist Francisco Oller (1833–1917) produced numerous portraits of US officials newly arrived on the island.1 US-appointed military officers, governors, and even President William McKinley counted among his subjects in the early years of the US imperialist regime. Today, many of these portraits line the walls of La Fortaleza, the official residence of the governor of Puerto Rico and the oldest functioning executive mansion in the hemisphere (fig. 1).2 Yet in spite of their prominent display in La Fortaleza, these portraits represent one of the more perplexing aspects of Oller’s oeuvre and occupy an uneasy position in histories of Puerto Rican art defined by a sense of national identity or puertorriqueñidad. Scholars of Oller’s work have largely shied away from considering paintings that appear so clearly inscribed within the US imperial project, and as a result, little is known of how these works were commissioned or of Oller’s political and financial motivations during this period.3

Fortunately, I have uncovered previously unpublished correspondence and documents in the Library of Congress pertaining to Oller’s portrait of Guy V. Henry (fig. 2), the third US-appointed governor-general of Puerto Rico.4 The painting in question presents the governor-general in the mode of a conventional military portrait. With golden epaulets perched upon his shoulders and his chest dotted with medals, Henry appears as a decorated war hero without a single discernable reference to his role within the complex political landscape of US-occupied Puerto Rico. The newly surfaced documents, however, serve to elucidate our understanding of Oller’s artistic endeavors as he navigated the political waters of the US imperialist regime. I uncovered this remarkable cache of letters, petitions, and receipts over the course of my research on Puerto Rican art in the age of US imperialism, a fortuitous discovery that has furthered my efforts to understand how Caribbean artists like Oller responded to US expansionism at the turn of the century.5

This exciting discovery came at a pivotal moment for the office of the governor in Puerto Rico, and indeed, Puerto Rican history. In the summer of 2019, islanders witnessed several governors come and go following the revelation of a profane group chat belonging to ex-governor Ricardo Roselló and other political elites. Rife with sexist and homophobic slurs, the leaked transcripts provoked horror and outrage from nearly every level of Puerto Rican society. Galvanized by feminist and LGBTQ+ activists, thousands of Puerto Ricans took to the streets, participating in mass protests throughout the island and the diaspora in the weeks that followed.6 After two weeks of demonstrations, Rosselló capitulated, submitting his official resignation and appointing former US Congressman Pedro Pierluisi as his handpicked successor.7 Yet within days, the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico declared the nomination unconstitutional, resulting in the appointment of Secretary of Justice Wanda Vázquez, the next in the line of succession, to the role of governor.8 After holding office for a mere thirteen months, Vázquez was defeated by none other than the ousted Pierluisi in a contentious primary challenge, clearing the path for the politico’s election in November 2020 in a final dramatic twist.

Creative expression was central to the demonstrations leading to Roselló’s ouster. Protestors marched to the distinctive beat of reggaeton, armed with drums, tambourines, cowbells, and makeshift noisemakers like cacerolas or pots and pans.9 As demonstrators flooded the streets of Old San Juan, prominent musical artists, including Latin trap artist Bad Bunny, rapper Residente and his sister iLe, and pop singer Ricky Martin, joined them on the scene.10 Most memorable was the deployment of perreo intenso or combativo, the “doggy style” dance closely associated with reggaeton, as the island youth danced in protest on the steps of the Cathedral of San Juan Bautista.11 In the weeks following the demonstrations, street artists could be spotted on the Calle Norzagaray at work on new murals to commemorate survivors of domestic and gender-based violence, sexual discrimination, and the victims of Hurricane Maria (fig. 3)

This dramatic intersection of art, politics, and the Office of the Governor in Puerto Rico frames my understanding of the events of more than one hundred years earlier as I turn to Oller’s portrait of Henry as a case study for conceptualizing the role of art in the wake of the War of 1898 and the US invasion of Puerto Rico. Oller’s correspondence and other relevant documents from the Library of Congress demonstrate that in the first years of the new US regime, the fine arts were deployed to gain the trust of the Puerto Rican people and to legitimize the US imperial project, often with complicated and sometimes disappointing results. In looking to Oller’s portrait of Henry, this research note explores the ways Oller’s aspirations were both aligned with and ultimately unfulfilled by the promises of US imperialism.

Oller painted his portrait of Henry in the immediate aftermath of the War of 1898 and the US occupation of Puerto Rico as part of his late career foray into imperial portraiture. The invasion of Puerto Rico led by General Nelson Miles on July 25, 1898, was the final act of the four-month-long War of 1898 that resulted in the demise of the Spanish empire and the ascendancy of the United States as a major world power. The United States had formally declared war on Spain as an act of retaliation for the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor and with the expressed intent of liberating Cuba from Spanish misrule. Following a blockade and bombardment of San Juan’s harbor in 1898, US troops invaded Puerto Rico, and after a mere three months, the “splendid little war” concluded with Spain ceding Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States.12 In this short period, the United States had established what Lanny Thompson terms the “imperial archipelago:” an overseas empire of insular possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific.13

Prior to his downfall, former governor Roselló sought to end Puerto Rico’s status as “the oldest and most populous colony in the world” by pushing for the island’s admittance as the fifty-first state.14 Yet for much of Puerto Rico’s history, the Office of the Governor has served to enforce and maintain colonial power on the island. The Puerto Rican governorship is the oldest in the Americas, first occupied by the Spanish colonizer Juan Ponce de Leon in 1509. Following the transition from Spanish to US rule, governors were appointed directly by the president of the United States until 1948, when reforms resulted in the ascendance of Luis Muñoz Marín as the first elected governor of Puerto Rico.15 Much like the events of July 2019, the Office of the Governor in Puerto Rico was held by a rapid succession of individuals in the wake of the War of 1898. General Nelson Miles was appointed military governor in charge of the Army of Occupation and civil affairs on the island. Within a few months, Miles resigned the position and was succeeded by General John R. Brooke, who soon transferred his authority to Henry by the end of 1898.16 During his tenure as governor, Henry pursued forceful government, health, sanitation, tax, and education reforms on the island. Seeking to facilitate the implementation of his programs and consolidate US hegemony, Henry instituted fierce censorship of the Puerto Rican press and dissolved the Insular Council, a governing body that possessed a measure of autonomy prior to the US invasion.17

Oller’s undertaking of the commission for Henry’s portrait may seem surprising, as the artist is primarily known by scholars on the mainland for his still lifes and landscapes that bear the traces of his participation in the French Impressionist movement. Extended transatlantic sojourns to France from 1858 to 1865 and from 1873 to 1884 defined Oller’s artistic career. During these Parisian interludes, the artist painted alongside Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), neither of whom possessed experience with official portraiture. In light of Oller’s impressionist sensibilities and Henry’s authoritarian tactics, the painter’s acceptance of the commission for the former governor’s portrait may strike us as dissonant. However, Oller returned from Paris to San Juan with a conception of modern artistic practice as a social, political, and religious mission that endeavored to contribute positively to society. His imperial portraits should be viewed within this framework.18

For many Puerto Ricans like Oller, the ascendency of the United States represented “a positive break with the past” after centuries of Spanish oppression and misrule.19 The first two political parties organized on the island after 1898 strongly favored the incorporation of Puerto Rico into a territory of the United States in preparation for statehood, with optimistic Puerto Ricans imagining the United States as a “State of States and a Republic of Republics” to which Puerto Rico might someday belong.20 Prominent Puerto Ricans sought new opportunities in the US regime, accepting administrative positions within the sprawling colonial bureaucracy.21 For his part, Oller looked to the United States as a new source of patronage for his artistic and educational endeavors. In an open letter to the secretary of development published in La Correspondencia de Puerto Rico at the beginning of Henry’s tenure, Oller suggested that the new US regime offered an opportunity to modernize Puerto Rico’s arts education system; the artist noted that while his previous endeavors to institute a system of arts education in Puerto Rico had failed, the island “was governed in a different manner than it is today.”22 Oller would be appointed instructor of drawing at the newly established Normal School in 1903, perhaps due in part to his favorable views of US governance.23

The documents from the Library of Congress reveal that Oller and a handful of notable Puerto Ricans and US officials planned to commemorate Henry’s tenure as governor by commissioning a portrait in his honor. A letter from the archive describes the portrait as “paid for by popular Puerto Rican subscription, intended as an honor to the recent governor-general, the purpose being to hang it in a public place.”24 Roberto H. Todd Wells, a native of the neighboring island of St. Thomas and one of the founders of the Puerto Rican Republican Party, served as a treasurer for the project.25 Of the two major political parties formed in the wake of the US occupation, the Republicans were particularly amenable to Henry’s undertakings over the course of his tenure as governor.26 In addition to Todd Wells, subscribers of the portrait included Cayetano Coll y Toste, esteemed historian of Puerto Rico and the secretary of finance in the restructured insular government; Francisco de P. Acuña, secretary of state; and more than a dozen additional Puerto Rican bureaucrats in the Department of Public Works. As plans for the commission unfolded, US officials suggested that a committee be assembled to evaluate the artistic merit of the work following its completion. Among the nominees for the committee was Federico Degetau, a prominent Puerto Rican art collector and politician who would become the first resident commissioner of Puerto Rico, the island’s nonvoting delegate to the US House of Representatives. The use of subscriptions and committees, as conceived by both US officials and the Puerto Rican elite, advanced a vision of US governance as egalitarian and democratic; while residents of Puerto Rico did not have a say in the appointment of their governor, they could determine his likeness.

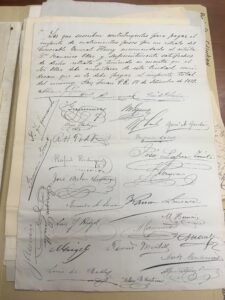

Despite the façade of optimism and cooperation, Oller’s relationship with the new US regime quickly turned fraught, culminating in his termination from his appointment at the Normal School in 1904.27 Evidence of tensions between Oller and US officials can be gleaned from the documents at the Library of Congress. Oller claimed that US officials failed to compensate him as agreed for Henry’s portrait. In order to resolve the matter, Oller drafted a petition demanding for the amount to be paid in full. The petition was written in his own hand, dated and signed by more than thirty subscribers to the portrait fund (fig. 4).28 Yet despite these protestations, the matter remained unresolved the following year. In a letter to Victor S. Clark, then president of the Insular Board of Education, Oller asserted that he had only received 325 of the allotted 400 pesos, prompting the artist to bring the case to the municipal court in San Juan.29 This radical measure apparently elicited a response from Francis L. Hills, the director of interior works in Puerto Rico, as well as an executive at a cotton manufacturing company in Mobile, Alabama. In a letter to Clark dated February 26, 1900, Hills accuses Oller of “extortion,” stating, “He knows as well as we do that the money is not due him. I’m sorry that he has given you this unnecessary trouble.”30

Despite his swift dismissal of Oller’s accusation, Hills reveals that there was indeed a surplus in the portrait fund:

There was a balance from the portrait fund of $65.82. . . . General Eaton and I consulted in Washington and decided to turn it over to Ms. Henry for the purpose of perfecting the very unsatisfactory portrait of General Henry which the chief of the Insular police presented to her. It was a very bad piece of work—very little likeness to the general and Mrs. Henry intended having it repainted, and it was to appear as Puerto Rican work because Mr. and Mrs. Henry did not want to offend the donors and accept the spirit of the gift. Mrs. Henry does not want it known that the work was not satisfactory, but I desire you to know where the money went.31

It seems that Hills and Inspector of Education John Eaton may have withheld the full payment amount on the grounds that the portrait was unsatisfactory. Indeed, Oller’s portrait falls short of its intended tribute to Anglo-Saxon masculinity. Oller made no attempts to flatter the sitter, likely working from photographs in the former governor’s absence in order to produce a realistic likeness. Though Henry appears firm and upright in full military regalia, he wears a bleak expression on a face emaciated and lined with age. With his left hand exposed, Henry dons a white cavalry gauntlet on his right hand, clutching its mate between his fingertips. Does it recall a white flag of surrender as it hangs limply in his grasp? Whatever Oller’s intentions, the finished portrait disturbed the artist’s US patrons, who avoided fulfilling their obligation to the artist while preserving their reputation amongst the island elite. Concluding his letter, Hills stated, “It is necessary to take EVERY PRECAUTION against insinuations and scandals when one is compelled to handle other people’s money in Puerto Rico.”32 The failure of US officials to meet their financial and professional obligation to Oller demonstrates the difficulties experienced by the artist as he strove to navigate the political waters of the new US regime, both as a Puerto Rican patriot and a newly minted imperial subject. Despite Oller’s strategic and ideological investment in the promises of a US empire, his attempts to advance his own artistic and educational endeavors were ultimately stymied by the paternalism of US colonial officials and the asymmetrical power relations between the United States and Puerto Rico, an imbalance that persists to this day.

In spite of the controversy surrounding the Henry commission, Oller continued to paint portraits of US officials in the first years of the US regime. Between 1898 and1907, Oller produced successive portraits of each US-appointed governor, including George Whitfield Davis (1899–1901), William Henry Hunt (1901–4), and Beekman Winthrop (1904–7). Today, these portraits line the walls of La Fortaleza’s Sálon Oller, reminding tourists and visiting dignitaries of Puerto Rico’s neocolonial status. While the closure of La Fortaleza during the July 2019 protests ensured the safety of Oller’s work, Rosselló’s image was not so fortunate. At the height of the demonstrations, a group of women unceremoniously removed one of the many official portraits of the former governor around San Juan from the wall of the local DMV.33 The Capitolio, it was decided, would not include a portrait of Rosselló among the busts of Puerto Rican governors lining the grand central hall. That honor is reserved for governors who complete their terms.

Cite this article: Natalia Ángeles Vieyra, “Problem Portraits: Francisco Oller in the Age of US Imperialism,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12642.

PDF: Vieyra, Problem Portraits

Notes

- The name of the conflict has been subject to revision in recent decades. Thomas Paterson, for example, suggests that the events of 1898 might be better remembered as the “Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War” to represent the parties involved; see “U.S. Intervention in Cuba, 1898: Interpreting the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War,” OAH Magazine of History 12, no. 3 (Spring 1998): 5–10. In Spain, the conflict is known as El Desastre de ’98 (The Disaster) or La Guerra de Cuba (The Cuban War). Recently, Taína Caragol and Kate Lemay, curators of the exhibition project 1898: The American Imperium (working title) at the National Portrait Gallery, have adopted the simplified moniker “War of 1898,” already in use by several scholars; see “Imperial Visions and Revisions,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10096). For simplicity and clarity, I have chosen to follow the latter example. ↵

- “La Fortaleza and San Juan National Historic Site in Puerto Rico,” UNESCO, accessed September 12, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/266. ↵

- A notable exception is Edward Sullivan, “Conflicted Affinities: Francisco Oller and William McKinley,” in From San Juan to Paris and Back: Francisco Oller and Caribbean Art in the Era of Impressionism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 159–75. However, Sullivan does not include substantial information on Oller’s US patrons. ↵

- Oller’s Portrait of Guy V. Henry has never been published in full color, and the closure of La Fortaleza to visitors following the 2019 protests prevented me from obtaining a high-resolution reproduction. The reproduction here is a historic photograph contemporaneous with the creation of the work, courtesy of the Archivo General de Puerto Rico. ↵

- See Natalia Ángeles Vieyra, “Fragmentary Impressions: Camille Pissarro and Francisco Oller in the Americas, 1848–1898” (PhD diss., Temple University, 2021). ↵

- Patricia Mazzei, “Puerto Rico Leadership in Turmoil Amid Calls for Ricardo Rosselló to Resign,” New York Times, July 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/14/us/puerto-rico-rossello.html; Isaac Chotiner, “The Frustration Behind Puerto Rico’s Popular Movement,” New Yorker, July 25, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-frustration-behind-puerto-ricos-popular-movement. ↵

- Frances Robles and Patricia Mazzei, “Puerto Rico Governor Names Pedro Pierluisi as His Possible Successor,” New York Times, July 31, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/31/us/pedro-pierluisi-puerto-rico-governor.html. ↵

- Jose A. Del Real and Frances Robles, “Who Is Wanda Vázquez, Puerto Rico’s New Governor?,” New York Times, July 24, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/24/us/puerto-rico-wanda-vasquez-governor.html; Patricia Mazzei, “Puerto Rico’s Governor Lost Her Primary Bid for a Full Term,” New York Times, August 17, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/17/us/elections/puerto-ricos-governor-lost-her-primary-bid-for-a-full-term.html; Frances Robles, “Thousands of Uncounted Votes Found a Week After Election in Puerto Rico,” New York Times, November 11, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/11/us/puerto-rico-ballots.html. ↵

- Yara Símon, “#CacerolaGirl Has Gone Viral for Her One-Person Cacerolazo Protesting Puerto Rican Cops,” Remezcla, July 23, 2019, https://remezcla.com/lists/culture/cacerola-girl-puerto-rico-protests. ↵

- Frances Robles, “‘Sharpening the Knives’: Musicians Join the Protests in Puerto Rico,” New York Times, July 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/19/us/puerto-rico-residente-ile-afilando-los-cuchillos.html. ↵

- Verónica Dávila and Marisol LeBrón, “How Music Took Down Puerto Rico’s Governor,” Washington Post, August 1, 2019, https://beta.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/08/01/how-music-took-down-puerto-ricos-governor. ↵

- Lanny Thompson, Imperial Archipelago: Representation and Rule in the Insular Territories under U.S. Dominion after 1898 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2016), 22; Alfred W. McCoy and Francisco A. Scarano, eds., Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2010), 234. ↵

- Thompson, Imperial Archipelago, 22. ↵

- Ricardo Roselló to President Donald J. Trump, quoted in Rafael Bernal, “Puerto Rico Governor Asks Trump to Consider Statehood,” The Hill, September 19, 2018, https://thehill.com/latino/407494-puerto-rico-governor-asks-trump-to-consider-statehood. ↵

- César J. Ayala and Rafael Bernabe, Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History Since 1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 158, 161. ↵

- “Military Government in Puerto Rico,” Library of Congress, accessed on September 13, 2019, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/milgovt.html. ↵

- Pedro A. Cabán, Constructing A Colonial People: Puerto Rico and The United States, 1898–1932 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1999), 51–53. ↵

- Albert Boime, “Oller and 19th Century Puerto Rican Nationalism,” in Francisco Oller: Un realista del impresionismo, ed. Marimar Benítez (Ponce: Museo de Arte de Ponce, 1983), 41. ↵

- Ayala and Bernabe, Puerto Rico in the American Century, 15. ↵

- Ayala and Bernabe, Puerto Rico in the American Century, 24. ↵

- Julian Go, “Domesticating Tutelage in Puerto Rico,” in American Empire and the Politics of Meaning: Elite Political Cultures in the Philippines and Puerto Rico During U.S. Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 55–92. ↵

- Francisco Oller, La correspondencia de Puerto Rico, December 18, 1898, 1. ↵

- Haydee Venegas, “Chronology,” in Benítez, Francisco Oller, 36. ↵

- Francis L. Hills to Victor S. Clark, September 14, 1899, Puerto Rican Collection, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress. ↵

- Cayetano Coll y Toste to Victor S. Clark, September 19, 1899, Puerto Rican Collection, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress. ↵

- Cabán, Constructing A Colonial People, 52. ↵

- Venegas, “Chronology,” 36. ↵

- Perhaps in order to add urgency to the matter, Oller included that “the artist would be leaving town,” referring to plans to attend the Exposition Universelle in Paris. However, Oller is not known to have traveled outside of Puerto Rico after his final trip to Paris in 1895. Francisco Oller, Petition regarding Portrait of Guy V. Henry, Puerto Rican Collection, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress. ↵

- Francisco Oller to Victor S. Clarke, January 8, 1900, Puerto Rican Collection, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress. ↵

- Francis L. Hills to Victor S. Clarke, February 26, 1900, Puerto Rican Collection, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress. ↵

- Hills to Clarke, February 26, 1900. ↵

- Hills to Clarke, February 26, 1900. ↵

- Patricia Mazzei and Frances Robles, “Puerto Ricans in Protests Say They’ve Had Enough,” New York Times, July 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/18/us/puerto-rico-rossello-governor-protests.html. ↵

About the Author(s): Natalia Ángeles Vieyra is Maher Curatorial Fellow of American Art at Harvard Art Museums