“Shutterbug?”: Black Women Photographers and the Politics of Self-Representation

PDF: Brady, Shutterbug?

Since its invention, the camera has been an object infused with power dynamics. Expressions such as “shooting” a location, “capturing” an image, and “taking” a photograph imply a sense of control and dominance within the act of photography.1 Hence, the photographer is a figure with a degree of agency over those framed by their lens, as their gaze and influence shape the image. While there is a collaboration between sitter and photographer, it is the photographer who has the ability to “shoot,” “capture,” and “take.” The position of professional “photographer” implies an authoritative gaze. It is interesting, therefore, to consider how groups who have been historically marginalized are imagined as “photographers”: how does power manifest within different photographic constructions of the professional “photographer”?

Black women make for particularly noteworthy case studies when considering representations of photographers. The career path of the photographer was one that was largely inaccessible to Black women for decades.2 From photography’s earliest days, some African American men attained careers in photography, yet the scientific connotations of early photography largely excluded women.3 Although the work of Black women photographers is beginning to receive more attention, this contemporary focus follows decades of underrepresentation within American art history.4 Throughout the early to mid-twentieth century, visual representations of professional Black women photographers were few and far between. The result of the dual constraints of racism and sexism, the scant representations of Black women as photographers evidence an intersection of gender, race, and class anxieties.5 These women’s absence in the white press and sexualization in the Black press demonstrate the ways in which the camera functioned as a potentially subversive object in the hands of Black women photographers. Through their own lenses, self-representations frequently demonstrate Black women using self-portraiture to advocate for their roles as businesswomen and working professionals.

The role of Black photographers as “ambassadors” to their communities has long been established in scholarship; historians such as Deborah Willis, bell hooks, and Richard Powell have reflected on Black photographers’ ability to challenge the white gaze and evoke self-agency.6 Even as photography became a more acceptable occupation for white women in the late nineteenth century, Black women were still largely excluded from the practice due to the prohibitive costs associated with the medium combined with the societal constraints of racism and sexism.7 Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe provides rich insight into the struggles faced by those who attempted to claim a career in photography, articulating the ways in which early Black women photographers’ stories and images have either been lost or absorbed into the narratives of their husbands.8 As such, while professional Black women photographers did exist, the space they occupied in the public sphere was minimal.

Representations of Black women photographers in white visual culture were practically nonexistent in the early to mid-twentieth century. Their role within white visual culture can be best characterized by its absence. Instead, stereotypical images of African American women as mammies or jezebels were prominent in white culture and were grounded in white-held notions of Black inferiority.9 The idea of a Black woman as an independent businesswoman in command of the images she took would directly combat racist notions of African American inferiority that dominated much of the early twentieth century. The potentially subversive image of a Black woman holding a camera was not compatible with notions of white supremacy. Even outside of a professional sphere, advertisements that suggested the camera as a hobby or amateur pastime were also cautious about portraying Black women as photographers.

The representations of Black women within advertisements for cameras exposes many of the anxieties surrounding Black women photographers, particularly as these ads were shaped overwhelmingly by white advertisers. Historian Brenna Wynn Greer articulates the ways in which, prior to World War II, white advertisements refused to acknowledge their potential Black customers, with brands like Coca-Cola visually excluding Black people from their vision of the “American Dream.”10 It was only as the postwar perception of the “Negro” market’s lucrative nature grew that advertisements from white businesses began to target Black people. Anxieties manifested about how best to represent Black women in these advertisements; for example, early Coca Cola advertisements favored models who represented a “plain Jane . . . a typical average American,” including Mary Cowser, who was scouted while she was a university student. The Black women models were to be attractive—Greer notes that Cowser had been named “most covetous beauty” by her school yearbook—but not necessarily glamorous.11 These anxieties were amplified by placing a camera in the hands of potential female photographers, even when presenting Black women as amateurs rather than professionals. By the early 1960s, as the camera became more accessible to the middle classes and advertisements representing African Americans continued to increase, Kodak was uniquely positioned to contribute to the construction of the Black woman photographer in the public imagination.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Kodak’s previous dominance of the photography industry in the United States was challenged by an increasingly competitive market. In 1963, however, the introduction of the Instamatic model made Kodak cameras more accessible to American consumers than ever before. As Jeffrey Sturchio notes, “This camera, using a cartridge-loaded film, was conceived in the grand tradition of Eastman’s original vision of making cameras as easy to use as a pencil”12—a loaded metaphor, considering the inaccessibility of literacy within formerly enslaved and disenfranchised communities. Historian Sarah Lewis highlights the color bias that remained present in Kodak film.13 Nonetheless, within this amateur market, Kodak followed the example set by Coca-Cola and began to pitch their products to Black audiences.

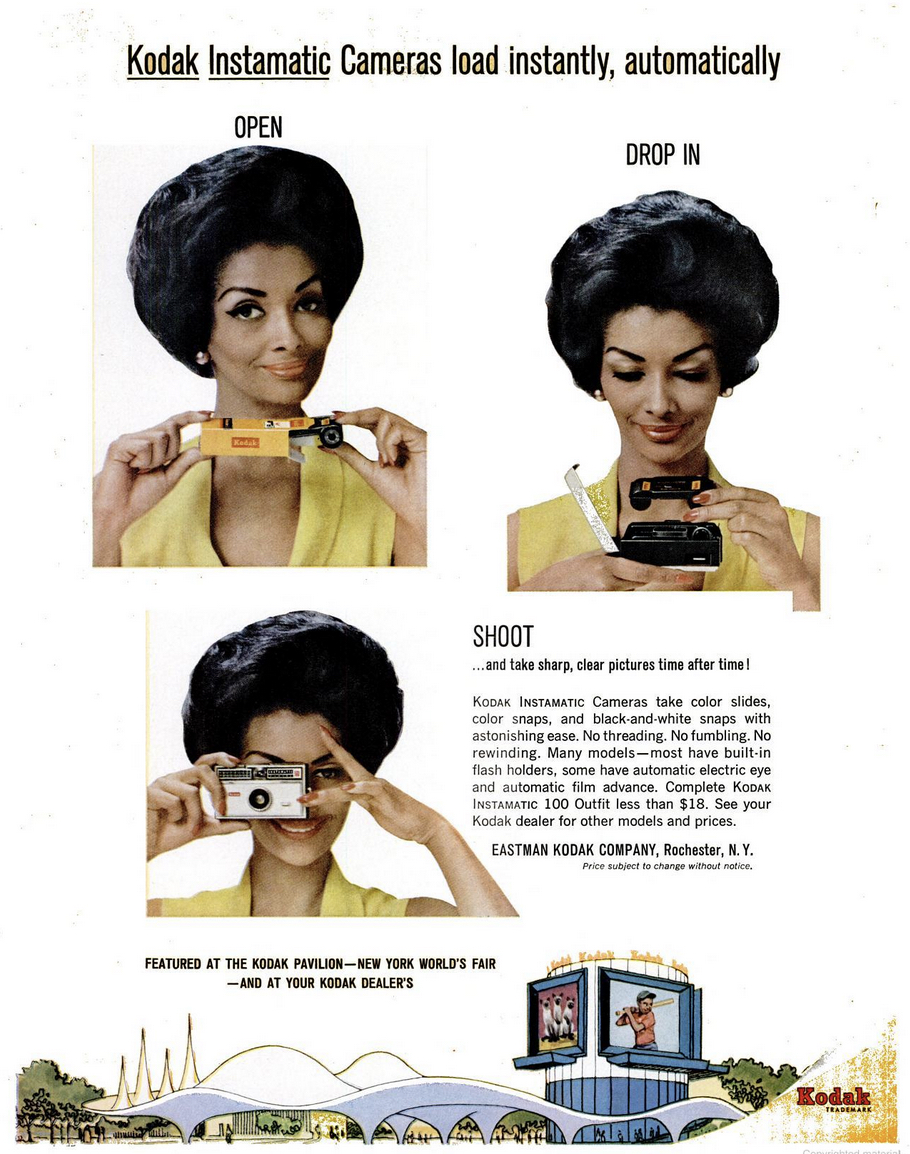

The first Kodak advertisement in Ebony appeared in August 1964 (fig. 1). A monthly photography magazine for Black people, launched by John H. Johnson after World War II, the publication aimed to show “the happier side” of African American life.14 Variations of Kodak’s advertisement featuring white women existed around the same time for white audiences. The Ebony advertisement shows three images of an African American woman, the model Helen Williams, opening, loading, and shooting a Kodak Instamatic camera. The use of Williams in this image is notable, as she was an established model at the time, often being paid between fifty and one hundred dollars per hour.15 Clearly by 1964, advertisers had moved away from the postwar emphasis on plain Janes, opting for professional models. Historian Tanisha F. Ford points out that much of the modeling and advertising industry “lauded whiteness” at this time, and while Ebony described Williams as “amber-brown” and “America’s most successful negro model,” she is an example of “the insistence upon light-skinned beauty with reified colorism within the black community . . . [that] linked modern black beauty with fair skin and straight hair.”16 Hence, white advertisers defined beauty standards within a white gaze, even when using Black models to sell to a Black audience.

The subversive potential of the camera is also undermined. Although Williams is pictured with the camera and meets the gaze of the viewer directly as she confidently uses it, the Kodak branding reinforces the simplicity and lack of skill required to do so. As such, white advertisements directed at Black communities pictured Black women photographers as distinctly amateur photographers.

From December 1964 onward, several Kodak advertisements featuring Black women ran in the magazine, bearing slogans like “All Kodak Gifts Say ‘Open Me First’” and “Save Your Christmas in Pictures.”17 Two of the three advertisements of this type show a woman being gifted a camera by a man within an implied familial context. As such, the camera is constructed as a sentimental object through which family Christmases can be recorded. The later advertisement of December 1966 shows a Black woman holding the camera and smiling, while the text surrounding the advertisement emphasizes the Kodak camera’s ease of use. That so many advertisements appeared around Christmas is significant, as it served to highlight the sentimental nature of gifting a camera to document family events within private, domestic spaces. As such, the amateur and sentimental nature of the camera is heightened.

In contrast to white media interpretations, depictions of Black women imagined as photographers were present in the Black press. What is particularly notable is that Black women with cameras were most frequently represented in the Black press as pinups rather than as professional photographers. This was particularly the case in Jet magazine, which was founded in 1951 as “a publication of the black working class, or the ‘black masses.’”18 Compared to Ebony, Jet’s cheaper price, smaller size, and weekly rather than monthly publication made it instantly popular. However, a similarity of both Ebony and Jet magazines was their utilization of sex in order to attract readers. Greer writes that pinups, or “cheesecake” photographs, were crucial to the success of both Ebony and Jet:

Whereas such images gradually increased in appearance in the pages of Ebony, they were ubiquitous in and on Jet from inception, precisely because of their proven popularity through Ebony. Busty women with bare shoulders, bare midriffs (navels and all), and bare legs were a staple of the magazine’s covers, and every issue included a two-page pin-up spread.19

These publications’ efforts to portray African American women as desirable is important. It is consistent with the theme of “Black is Beautiful” and rejects the long history of Black women being depicted as lesser or discouraged from embracing their beauty within white media. Nevertheless, the representations of Black women photographers reveal the ways in which the camera holds the potential to symbolize agency, power, and control—and how these connotations can be subverted by staging and text.

Black pinup models holding cameras can be seen in editions of Jet magazine from 1960 and 1962. In both images, Black women are depicted pointing cameras toward the viewer, literally reflecting and deflecting the viewer’s gaze. As such, the camera affords the posing woman a sense of subversion and defiance. Rather than merely being observed, she can also observe the viewer. The women in the photographs are presented as possessing a certain agency, while their smiles indicate the good-natured and desirable quality of such an interaction. Yet there are significant limits to the inversion of power dynamics afforded in both of these images, by their staging and by their captions. In the 1960 feature, a young woman on her knees is identified as Beverly; she is shown smiling and looking slightly up at the viewer. She holds a camera in her hands, pointing outward, yet it is held away from her face, belying her intent to actually photograph the “viewer.” Simultaneously, the caption reassures the viewer that the “camera is a ‘prop,’” thereby emphasizing the photograph as a fictional construct before listing Beverley’s actual hobbies as “sewing, modeling.” Tony Rhoden’s 1962 photo shows two women (Jean Turnbo and Jacqueline Paradise) using their cameras to return the viewer’s gaze while their pictures are taken by two male photographers. The caption explains that the women are “getting posing pointers” from the two men. As such, the potential subversion of the camera is limited by both the gaze of the photographers and the status of the women as learning from the men. Although their outfits are not as revealing as the swimsuit worn by Beverly, the staging of the photograph centers on the exposed legs of the models. Hence, the camera’s potential for subverting the sexualized gaze of the viewer is undermined by both staging and captioning.

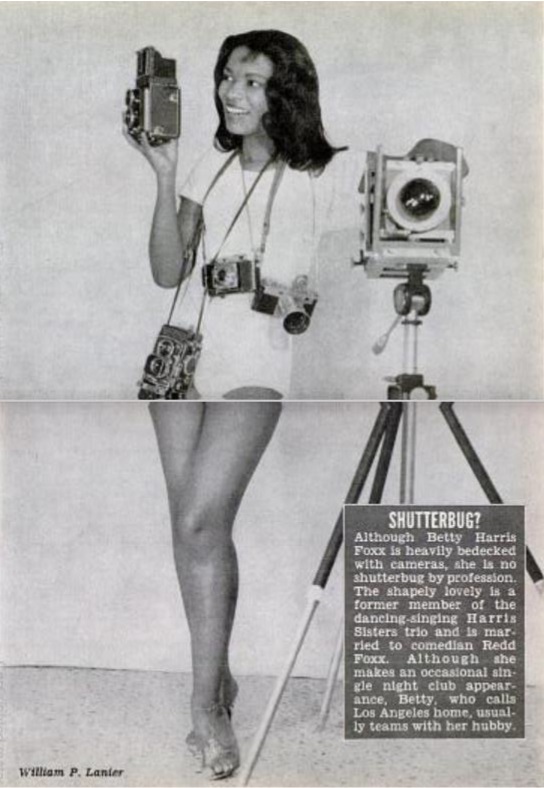

The double-page image of Betty Harris Foxx from the January 1960 edition of Jet evokes similar tensions (fig. 2). The spread shows a full-body image of Foxx: one hand rests on a large camera on a tripod, the other holds a camera up to her face, and several other cameras hang around her neck. Foxx is wearing a short white one-piece and looks at the camera in her hand, a smile on her face. The subversive potential of this photograph is clear, as Foxx rests her hand on a large camera that directly faces the viewer. The image’s inclusion of several cameras implies that she is familiar with the technology. However, as with the aforementioned photos, the image’s staging and captions undermine this potential. Foxx does not gaze at the viewer with her lenses; rather, she looks to the side, smiling. The cameras are kept largely to the top half of the image, with just as much space dedicated to her bare legs. Notably, the title directly questions Foxx’s identity as the photographer, asking: “Shutterbug?” The caption further counters any implication that Foxx might be a photographer, stating, “Although Betty Harris Foxx is heavily bedecked with cameras, she is no shutterbug by profession.” Within the pages of Jet magazine, Black women are imagined as photographers within sexualized contexts rather than professional ones. The Black woman photographer is a fantasy figure—one who can redirect the gaze of the viewer back at them, playfully challenging them. However, any serious inversion of power is undercut by the textual framing, staging, and sexualization, which remind viewers that the women pictured are not “real” photographers.

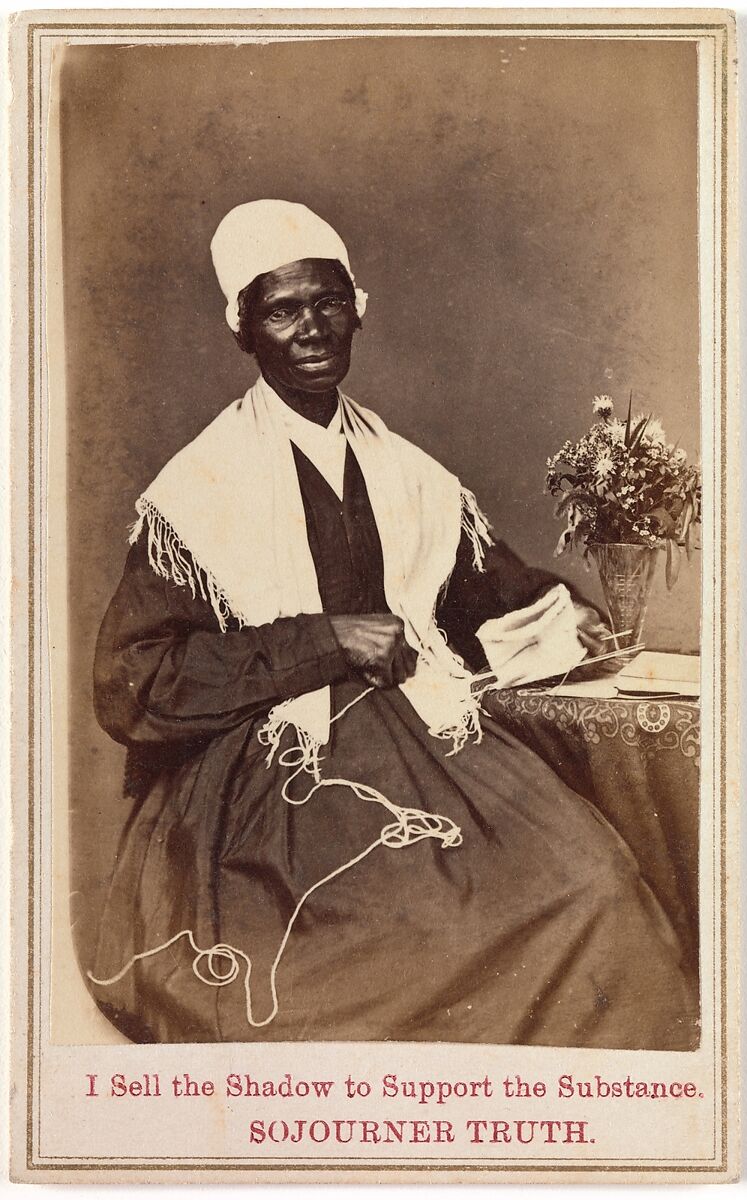

It is important, therefore, to consider the ways in which Black women did turn their own lenses on themselves. However, it must first be noted that Black women’s interactions with the camera can be extended beyond that of “photographer.” Many Black women have utilized the camera for self-representation without being the photographer themselves. The portraits of abolitionist Sojourner Truth in the nineteenth century are a well-documented example of such an exchange (fig. 3). Truth was an active agent in the construction of her image, as her cartes de visite were branded with a recognizable slogan that identified them as hers: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”20 Augusta Rohrbach wrote of Truth that her “command of her image through her active use of iconography, legal protection, and marketing exposes Truth in her various roles as artful purveyor, producer, and product.”21 Truth actively shaped the reproduction of her image and engaged with the photographic process at every stage. Although Truth may not have pressed the button to take the photograph, her active role in the construction of her image, I argue, could define such work as a self-portrait. Art historian Dawn M. Wilson asserts that within self-portraiture, “the artist’s conscious agency is depicted as the controlling influence in these self-portraits, rather than the camera mechanism.”22 As such, Black women like Truth could cultivate agency through photographic self-representations. By claiming space within the frame, they subverted the gaze and power dynamics that excluded them from the field.

The ways in which Black women photographers chose to represent themselves is therefore significant. In Moutoussamy-Ashe’s catalogue of photographers, it is notable that over half of the book’s entries prior to 1970 include not just portraits of the women themselves but photographs of women holding cameras.23 While there is doubtlessly a degree of Moutoussamy-Ashe’s own editorial hand shaping the inclusion of these images, the fact that so many of these photographs exist is notable. The use of significant objects in photographs harks back to Truth’s use of props, and the way she combined the “garb of Quaker womanhood” with a headwrap that “references an African past” set precedents that would be mirrored in the twentieth century.24 Yet the inclusion of the camera extends beyond merely the use of props—the photographers’ cameras demonstrate their professionalism and mastery of their craft.

Within the realm of photojournalism, Vera Jackson’s self-portrait speaks to this inclination toward professionalism and self-empowerment in the 1940s and 1950s.25 In her photographs of celebrities made while working at the Black-owned newspaper the California Eagle, Jackson demonstrates her emphasis on making African Americans look good, stating that she “worked hard at it to put the best foot forward in every picture.”26 In this self-portrait, Jackson is dressed in a way that would connote respectability and professionalism at this time. She holds the camera and flashbulb, conveying comfortable familiarity with the object. One hand rests underneath the camera while the other holds the flashbulb. As in other African American women’s self-portraits, the camera remains a prop within the image but one with which the subject is intimately familiar. In these ways, Jackson represents herself as a respectable and professional businesswoman.

Elizabeth “Tex” Williams’s entry in Moutoussamy-Ashe’s book includes multiple images of her wielding a camera, as well as wearing her military uniform. Williams was the first Black woman photographer in the US military and joined the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in 1944. Williams’s photographs commonly show African American military personnel hard at work and engrossed in their tasks. Williams herself is photographed with a camera, taking ID photos, or in the lab.27 In all of these photographs, Williams wears her uniform and is using or holding her professional equipment. Particularly notable is the image of Williams with a vehicle, her leg raised up on the car, as she holds the camera and bears a heavy-looking box on her back.28 She appears confident and self-assured, with a level of professionalism compounded by both her uniform and handling of equipment.

This image evokes a less traditional respectability than the image of Jackson, since Williams’s pose can be interpreted as somewhat masculine. It rejects any “promise of protection,” which historian Farah Jasmine Griffin defines as a set of patriarchal shields by Black men of fellow Black women that both “restores a sense of masculinity to black men while granting black women at least one of the privileges of femininity,” while still relying on women assuming a “stance of victimization” with a lack of agency.29 Such protections often led to African American women being portrayed as victims deserving of sympathy, and so portraiture often displayed African American women according to the aesthetic standards of white womanhood. In Williams’s photography, however, we see a rejection of this standard and a move toward a more masculine interpretation: in the 1940s or 1950s, adopting a stance with a leg on a car, signifying ownership, would have been unusual for a Black woman. In this way, Williams bolsters her role in any “power struggle” that the politics of respectability may dictate; she evokes professionalism by wearing a uniform yet assumes a pose that rejects femininity. Historian E. Francis White states that “to be positioned outside the ‘protection’ of womanhood was to be labelled unrespectable.”30 Yet here, Williams’s stance, uniform, and technical competence assert her own role as protector—of herself and of other American citizens.31

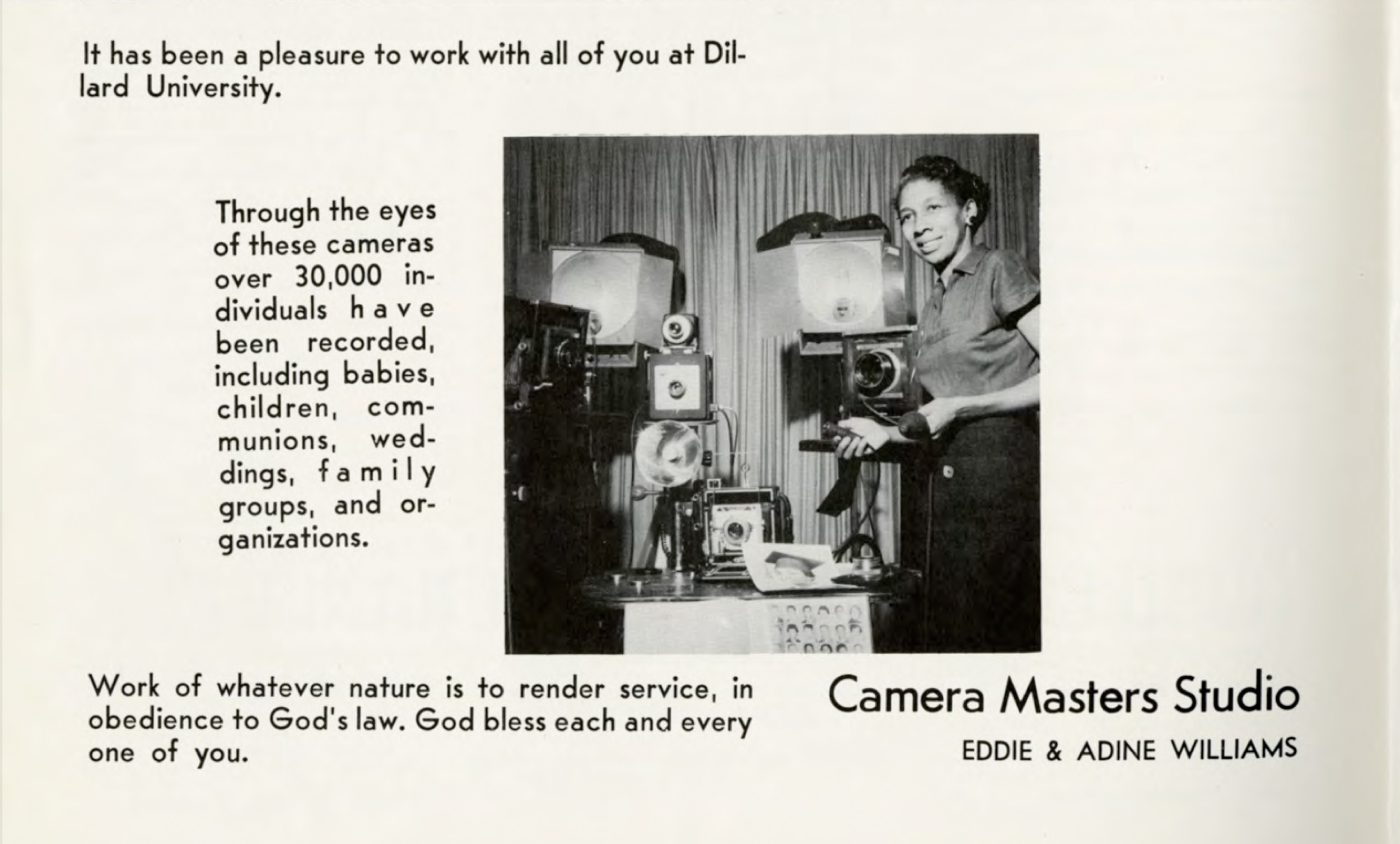

Finally, considering the ways Black women photographers utilize self-representation further demonstrates how the camera functions as an object to assign authority and power within an image. Notably, several Black women photographers employ images of themselves with cameras as part of their marketing strategies. Adine Williams was a portrait photographer who operated several different studios in the South throughout her life, including the Camera Masters Studio, which she ran with her second husband, Eddie Williams. The pair were commissioned to create portraits for the 1957 yearbook of Dillard University—a historically Black college in New Orleans (fig. 4).

The “Finis” section at the end of the yearbook reveals that Williams assisted in taking and compiling the photographs for this collection, with editor Bernard E. Rogers thanking “Mr. and Mrs. Edward Williams of Camera Masters Studio who went above and beyond contract and fees in supplying us with deadline pictures.”32 Within the image of this advertisement, Williams occupies space prominently and frames herself to the right of several pieces of camera equipment. Cameras, lights, tripods, and copies of photographs adorn the table next to which Williams stands, holding the equipment in her hands. Her expertise is compounded by the advertisement’s caption, which reads, “Through the eyes of these cameras over 30,000 individuals have been recorded.”33 Although the advertisement is credited to “Eddie and Adine Williams,” Williams’s central positioning in the ad advocates for her significant role. Hence, Williams orients her own skill with the camera as key to her studio’s marketing strategy.

Williams was not the first to utilize such a marketing technique, with Florestine Collins of New Orleans including photographs of herself in an advertisement in the Crescent City Pictorial in 1926 (fig. 5). A Creole woman who defied convention in order to successfully operate her own studio from 1920 to 1949, Collins created portraits of children and families that became a key part of Black social life in New Orleans. Historian Arthé A. Anthony explores the ways in which this advertisement for Collins can be heralded as “an exemplar of black progress.”34 The central photograph shows Collins in a typical portrait of the time, wearing a white dress and smiling at the camera. The image of Collins on the right is also significant, however, since it represents Collins as a photographer. Her back is to us, and her attention is focused on the boy she is photographing. Within the frame, Collins is surrounded by technical equipment, but her white clothing makes her stand out against the dark background. As such, the image projects the sense of Collins as a competent photographer in control of her own studio space. Within this advertisement, the two images work together to advocate for Collins’s business acumen.

The image of the Black woman photographer was a battleground of racism, colorism, and sexism. When considering Black women as amateur photographers, white advertisers evoked domestic spaces and sentimentality to sell cameras. The role of the professional photographer was entirely absent in such depictions. Where the idea of photographer as professional was evoked within the Black press, the image was sexualized and designed to titillate the viewer. In Black women’s self-representations, however, we finally see women who worked with the camera representing themselves with pride and agency, in control of their equipment and their space. Ultimately, the contentions surrounding the construction of the Black woman photographer reveal the ways in which anxieties surrounding Black women’s agency manifest—and how empowering work is created when cameras are in the hands of the subjects themselves.

Cite this article: Emily Brady, “‘Shutterbug?’: Black Women Photographers and the Politics of Self-Representation,” in “Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist,” In the Round, ed. Ellery E. Foutch, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17322.

Notes

- For more on the gun/eye, shooting/seeing metaphor, see Alan C. Braddock, “Shooting the Beholder: Charles Schreyvogel and the Spectacle of Gun Vision,” American Art 20, no. 1 (2006): 36–59. ↵

- Moutoussamy-Ashe and Marion Kilson, “Black Women in the Professions, 1890–1970,” Monthly Labor Review 100, no. 5 (May 1977): 39. ↵

- Deborah Willis, Black Photographers, 1840–1940: An Illustrated Bio-Bibliography (New York: Garland, 1985), 3–7. ↵

- See recent exhibitions on photographer Ming Smith, including Project: Ming Smith at the Museum of Modern Art (2023) and Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop at the Whitney Museum of American Art (2020–21). ↵

- bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (Boston: South End, 1982); Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1, no. 8 (1989): 139–67; Frances M. Beal, “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female,” Meridians 8, no. 2 (2008): 166–76. ↵

- Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000), 35; bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End, 1992),123; Richard J. Powell, Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 7. ↵

- For more on the intersection of gender and pictorialism, see Naomi Rosenblum, A History of Women Photographers (London: Abbeville, 1994). ↵

- Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (New York: Writers and Readers, 1985). ↵

- Melissa V. Harris-Perry, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011). ↵

- Brenna Wynn Greer, Represented: The Black Imagemakers Who Reimagined American Citizenship (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 224. ↵

- Greer, Represented, 234. ↵

- Jeffrey Sturchio, “Festschrift: Experimenting with Research; Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the Challenges of Diversification,” Science Museum Group Journal 13 (Spring 2020), http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-13/festschrift-experimenting-with-research. ↵

- Sarah Lewis, “The Racial Bias Built into Photography,” New York Times, April 25, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/25/lens/sarah-lewis-racial-bias-photography.html. ↵

- Megan E. Williams, “‘Meet the Real Lena Horne’: Representations of Lena Horne in Ebony Magazine, 1945–1949,” Journal of American Studies 43, no. 1 (May 2009): 117–30. ↵

- Malia McAndrew, “A Twentieth-Century Triangle Trade: Selling Black Beauty at Home and Abroad, 1945–1965,” Enterprise and Society 11, no. 4 (December 2010): 793. ↵

- Tanisha C. Ford, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 45. ↵

- Examples of advertisements bearing this slogan can be seen in Ebony (August 1964): 47; Ebony (December 1964): 49; Ebony (December 1965): 89; Ebony (December 1966): 47. ↵

- Greer, Represented, 177. ↵

- Greer, Represented, 187. ↵

- Mandy Reid, “Selling Shadows and Substance: Photographing Race in the United States, 1850–1870s,” Early Popular Visual Culture 4, no. 3 (February 2007): 296. ↵

- Augusta Rohrbach, “Shadow and Substance: Sojourner Truth in Black and White,” in Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, ed. Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 90. ↵

- Dawn M. Wilson, “Facing the Camera: Self-Portraits of Photographers as Artists,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70, no. 1 (January 2012): 60. ↵

- This data comes from surveying the entries in Moutoussamy-Ashe’s Viewfinders. Prior to 1970, there are twenty-two photographers who have images alongside their entries. Of these twenty-two, twelve feature self-portraits holding a camera. ↵

- Rohrbach, “Shadow and Substance,” 88, 85, respectively. ↵

- Vera Jackson, The Photographer, date unknown, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (New York: Writers and Readers, 1985), 85. ↵

- Vera Jackson, transcript from The Black Press: Soldiers without Swords, dir. Stanley Nelson, PBS, accessed July 30, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/blackpress/film/transcripts/jackson.html. ↵

- Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders, 98–104. ↵

- Unknown photographer, “Tex” on assignment, date unknown. Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (New York: Writers and Readers, 1985), 98. ↵

- Farah Jasmine Griffin, “Black Feminists and Du Bois: Respectability, Protection, and Beyond,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 568 (March 2000): 35. ↵

- E. Frances White, Dark Continent of Our Bodies: Black Feminism and the Politics of Respectability (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 33. ↵

- This is not to assert that the military equals protection for all American citizens; rather, that wearing a US military uniform is an assertion of citizenship. Hence, wearing the uniform—and being documented as such—was an empowering act in defiance of white supremacy: Isidora Stankovic, “Tintype Stares and Regal Airs: Civil War Portrait Photography and Soldier,” Military Images 33, no. 4 (Autumn 2015): 57; Christopher S. Parker, Fighting for Democracy: Black Veterans and the Struggle Against White Supremacy in the Postwar South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009). ↵

- The 1957 Le Diable Bleu: The Yearbook of Dillard University, ed. Bernard E. Rogers, accessed January 20, 2021, https://ia803007.us.archive.org/18/items/1957LeDiableBleu/1957_le_diable_bleu_complete_pdf.pdf. ↵

- The 1957 Le Diable Bleu. ↵

- Arthé A. Anthony, Picturing Black New Orleans: A Creole Photographer’s View of the Early Twentieth Century (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012), 68. This advertisement was previously discussed by the author with consideration of Black motherhood: Emily Brady, “‘I Like to Make Pictures of Children’: African American Women Photographers and Wielding the Weapon of ‘Motherhood,’” in Black Matrilineage, Photography, and Representation: Another Way of Knowing, ed. Lesly Deschler Canossi and Zoraida Lopez-Diago (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022). ↵

About the Author(s): Emily Brady is the Broadbent Junior Research Fellow in American History at University of Oxford.