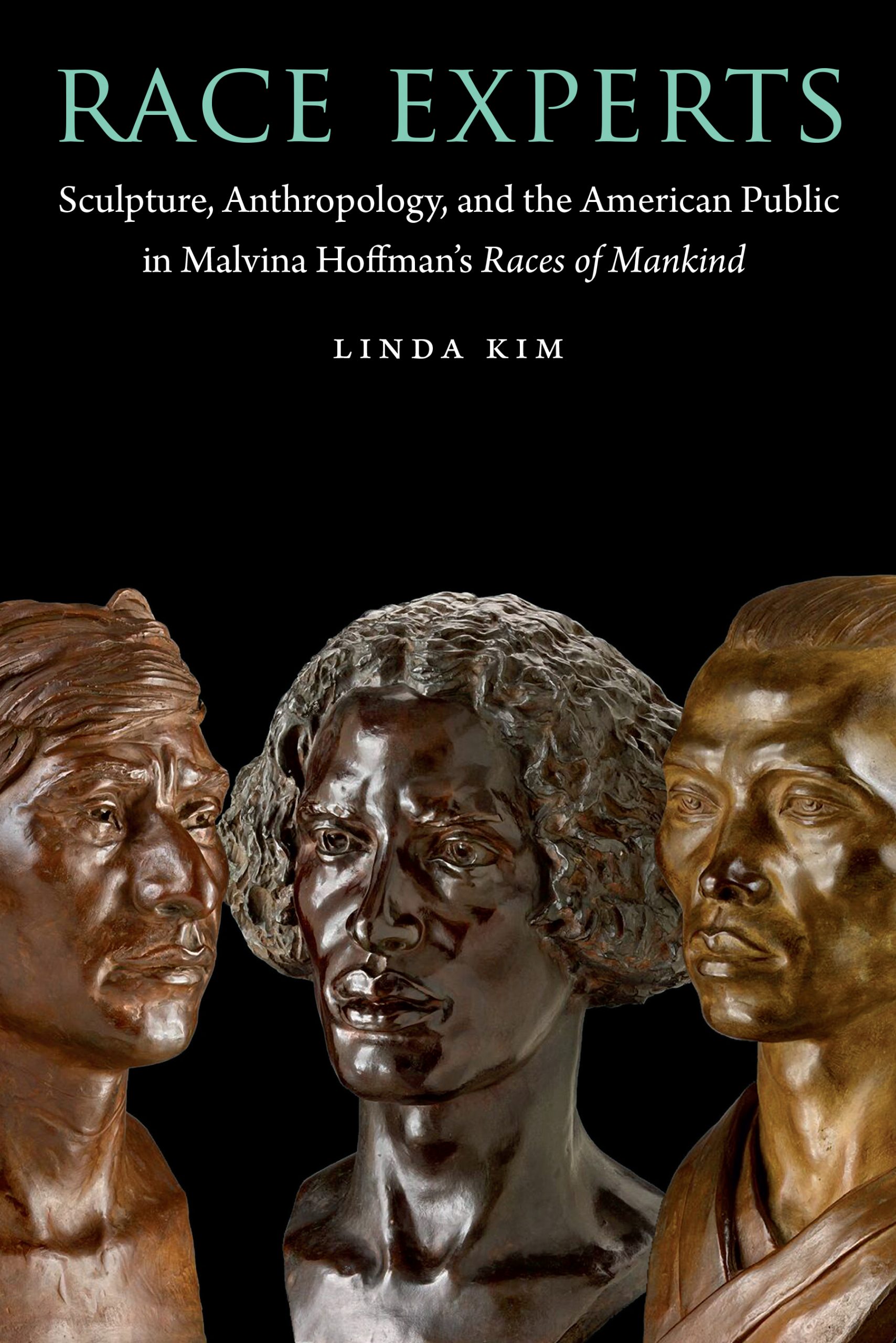

Race Experts: Sculpture, Anthropology, and the American Public in Malvina Hoffman’s Races of Mankind

by Linda Kim

by Linda Kim

Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2018. 420 pp.; 86 b/w illus; Hardcover: $60.00 (ISBN: 9781496201850)

In Race Experts: Sculpture, Anthropology, and the American Public in Malvina Hoffman’s Races of Mankind, Linda Kim combines research and theory from the fields of anthropology, ethnography, art history, and the histories of race and race science to consider Malvina Hoffman’s sculptures commissioned for the Field Museum of Natural History Museum in Chicago in the early 1930s. Kim has dug deep into the archives of the Field Museum and the American Museum of Natural History in New York in order to reconsider Hoffman’s work, entitled The Races of Mankind, as a mediating project between art, race, and anthropology. Her book focuses on the changing views of race, centering a conflict between what she calls “commonsense ideas about race” and the scientific-anthropological expert understanding of race in the 1930s. Kim argues: “The objective of the book is not to exonerate anthropology of its participation in the establishment of modern racial ideology, but to explain how race, in the early twentieth century, was also sustained by the commonsense worldview of everyday people . . . and how these two models of race—popular and scientific—diverged, clashed, and ultimately required the mediation of a third party to find common ground” (2). Malvina Hoffman functions as this third-party mediator. At the center of Race Experts, Kim considers the public reception of the Races of Mankind through a wide range of responses to the installation of Hoffman’s work in the past and present.

The book is organized into five chapters, with an introduction and conclusion. As Kim notes, “The Races of Mankind was the largest exhibit on race and the most extensive use of freestanding sculpture ever installed in a natural history museum” (4). In 1933, Hoffman unveiled more than fifty racial types in eighty-four life-size sculptures in the Hall of the Races of Mankind at the Field Museum of Natural History (seventeen additional sculptures were added in 1934). Twenty-seven of the sculptures were life-size; the remaining objects were shoulder- or half-length busts. The exhibition was arranged geographically, with the sculptures organized along continental divisions; smaller objects were placed in alcoves of the three interconnected galleries. Several multifigure compositions were arranged in narrative tableaux, including The Kalahari Bushman Family and The Cockfight Group. Kim points out that Hoffman was probably selected for the commission because her second cousin was married to Marshall Field III, one of the principal funders of the Hall of the Races of Mankind at the Field Museum.

Several ideas frame the book and are carefully laid out in the introduction: mediations, racialism, intentions, publics, borders, and fault lines. Various forms of mediation are traced throughout the book, including how the material form of sculpture acted as a “medium of racial epistemology” (13); how art had the potential to intervene between anthropological and commonsense ideas of race; and how Hoffman negotiated her knowledge of race through the medium of sculpture, the views of the museum’s science experts, and the public’s understanding of race. Kim does not use the terms “racist” or “racism,” instead turning to the ideas of “racialist” and “racialism.” Interestingly enough, however, the Oxford English Dictionary defines racialist and racialism as having been superseded by racist and racism. Kim deploys racialism to avoid labeling Hoffman a racist, attempting to nuance the concepts. Careful not to present Hoffman as a “racial savior,” Kim defines racialism in two ways: on the one hand, “racialism proposes the existence of discrete races that are represented by individuals who all share a common set of attributes. . . . But whereas racialism does not entail any evaluation of these differences in qualitative terms (superior or inferior), racism does” (19); on the other hand, racialism should be understood as an ideological construct that can have “critical social consequences” (19).

Kim also weaves intentions, publics, borders, and fault lines into her usage of mediation and racialism. She proposes that we should understand Hoffman’s intentions as under constant revision in the face of the contradictions inherent in the Field Museum project. Kim locates Hoffman’s ethnographic racial representations between the anthropological model of race, the artist’s visual understanding of race, and the commonsense (public) understanding of race. Turning to voices of anthropologists, museum professionals, the press, and the public response to The Races of Mankind, Kim underscores that publics should be understood as heterogeneous, often conflicted, and multi-voiced. The author also situates the idea of “borders” as central to her argument, noting that race was not a specifically American problem, but one that should be understood within the context of racial formations across cities, regions, and national lines. She writes: “Race was a form of epistemological expertise that was often highly localized and specialized” (25). Lastly, Kim considers the fault lines between science and popular ideas of race and the ways in which Hoffman negotiated between the two.

Chapter one examines the “strands of expertise” that went into the understanding and creation of The Races of Mankind, as well as “the emergence of a common-sense epistemology of race in 1930s America that disputed the experts on race” (33). Kim lays out in detail the collaboration of scientific and museological experts in the creation of the exhibition, as well as the challenges they faced. This chapter signals the diverse players involved in the project, including experts embedded in natural history museums; famed anthropologists and biologists of the era, including Franz Boas, Astley John Hilary Goodwin, and Eugen Fischer; and popular ideas of racial knowledge. Starting in 1930, Hoffman traveled the globe in pursuit of expert advice and subject matter, maintaining a sketchbook of portraits. For example, in 1931, Hoffman, at the suggestion of the museum, traveled to Europe to study racial taxonomy and identity, meeting Eugen Fisher, who was the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Berlin. Several years later, Fisher became a member of the Nazi Party (Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party) and was instrumental in promoting the idea of German racial superiority. Adolf Hitler read Fisher’s 1921 work on “race hygiene” and incorporated them into Mein Kampf. Although Kim briefly acknowledges Fisher’s importance to Nazi ideology and the 1935 Nuremburg Laws, she avoids a direct confrontation between what Hoffman may have learned from Fisher and his future work for the Nazis certifying racial purity (215). Instead, Kim positions Hoffman as a transactional expert on race, defined as “an agent who exercises her or his expertise in concert with other experts, extending this expertise to new practical realms” (64). Kim argues that Hoffman negotiated between scientific experts, popular understandings of race, and her own racialist understandings and expertise from working on the project and encountering the diverse group of individuals who would become the models for The Races of Mankind.

Kim focuses on the natural history museum and its exhibits in chapter two, and on Hoffman’s critical aesthetic intervention into “science’s articulation of race inside the natural history museum” (73). I found this chapter to be particularly satisfying in its discussion of the transformation of installation and display techniques in museums, as well as its focus on the mediating factor of realism. Hoffman introduced display strategies associated with the art museum into the natural history museum setting. She insisted that her ethnographic sculptures be displayed without glass cases, opened up for greater viewing and interaction from the public, like modern art. Kim also discusses Hoffman’s ties to realism in light of the rise of abstract sculpture in the 1930s. Hoffman’s commonsense realism was hailed as visually satisfying (“commonsensical,” in Kim’s terms) in the context of the natural history museum. The author concludes the chapter by proposing that “the realism of The Races of Mankind is therefore a highly mediated form of representation” based in popular iconography (circus posters, for example) and the artist’s aesthetic decisions to make objects that were readable to her 1930s audience (126).

In chapter three, Kim presents anthropology’s interest in typology and “precise measurements” while placing Hoffman’s artistic practice in opposition to the discipline’s quest for quantifiable data on race. Kim explores the role of portraiture in Hoffman’s sculpture practice, underscoring that the artist “modified the terms of anthropological typology in The Races of Mankind by presenting not a series of racial types but a series of racial portraits” (127). Proposing that racial types are tied to measuring and cataloging races of people, Kim states that portraiture seeks “embodiment, physical and psychological immediacy, and interpersonal connection” (127). She argues simultaneously that Hoffman reconfigured racial typology into racial portraiture through her practice of direct contact with living subjects, and that Hoffman created anonymous rather than individual representations. Because of Hoffman’s approach to portraiture, her limited time with her models, and the communication barriers she faced in talking with her models, Kim asserts that The Races of Mankind landed somewhere in the middle, between typologies and commonsense ideas about racial difference: “The representations of particular subjects in The Races of Mankind were always filtered through commonsense realism about race, submerging the individuals to the exhibit’s typological requirements” (165). In Kim’s complex argument, Hoffman both marked her subjects as singular and as generalized categories.

Exploring how geography “served as the common ground for expert and commonsense understandings of race,” Kim turns to the work of Arthur Keith to set up chapter four, as she did in chapter three.1 Kim uses Keith as a foil to explore “the geographical foundations of racial epistemology” (175). She argues that geography serves as another important framework for understanding The Races of Mankind and its presentation of a wide range of racial types. Kim asserts that “geography, specifically the geographic dispersion of anthropological expertise, can explain the proliferation of races in the exhibit, that the very spatial organization of anthropology created the generative conditions for race in the interwar years” (176). In this chapter, Kim engages a variety of material culture sources to support her argument about the ways that “American geographic media” shaped expert and commonsense views on race, including textbooks, National Geographic magazines, circuses, and World’s Fair displays.

Chapter five examines “micro-expertise” and finally gets at the problem of commonsense ideas of race. Here Kim argues that “1930s commonsense epistemologies of race were neither common nor sensible” (226). By the time I got to this chapter, I was unsure as to who was the American public that flickered in and out of view—whose commonsense understanding of race was Kim referring to throughout the text? Did she mean explicitly the commonsense of white museum visitors, a generic white public? Kim tackles these issues through an examination of two sculptures and the models who posed for Hoffman: Sylvester Long (the Black model whose face/body was sculpted to represent an Indian for Blackfoot Indian) and Tony Sansone (the Italian model for Nordic Man). Both models were well-known theatrical performers with distinct racial identities. Through a close reading of the men’s complicated relationship to racial identity and their performance of race, Kim asserts that Hoffman tapped into the men’s professional personas in order to construct representations of the “Indian” and “White” races. These were the first full-size figures that Hoffman created in her New York studio before she embarked on her extensive travels. It would seem that Hoffman recruited these two men out of convenience, and because they were well-known performers whose bodies represented ideal types for her.

In 1967, the Field Museum removed The Races of Mankind from view, deinstalling the sculpture and placing most of the objects in storage, with a few pieces placed around the museum in “interstitial spaces such as hallways, entrance lobbies, stairwells, and outside of restrooms and food courts” (269). In 2015, the museum decided to undertake conservation of Hoffman’s sculptures and to reinstall the work in a new exhibition, Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculpture of Malvina Hoffman, which opened in January 2016. In the conclusion of Race Matters, Kim considers this reinstallation through visitor interviews she conducted in the galleries in March 2016. Kim analyzes Looking at Ourselves in order to evaluate “how visitors make sense of its recuperation of The Races of Mankind from its problematic past life as a racial exhibit to its current disposition as a nonracial exhibit” (273). This chapter points out the shifting meaning of Hoffman’s project in the twenty-first century, and the impossibility of fully removing it from its ethnographic and racialist origins. Kim asserts that the value of the Hoffman’s sculptures is that they “provide an opportunity to understand in concrete terms structural relationships in the human world that appear too complex to grasp otherwise” (307).

At the end of her study, Kim resituates the project of The Races of Mankind as complicated, tied to anthropology and commonsense racial ideas of the 1930s, and Hoffman’s navigation as an outside expert on race through the creative process. She argues that we must understand Hoffman’s work as both implicated in racial ideas in its presentation of the bodies of others, and as an attempt to negotiate a new understanding of race between the anthropological endeavors of the Field Museum and the public’s commonsense ideas of race. At the end of reading Kim’s book, I still have questions about her use of the terms racialism and racialist. What are the ethics of moving from a discussion of racism to racialism, from racist to racialist? Does Kim’s use of racialism/racialist allow us to avoid the hard conversation about the complicity of ethnographic imagery in the colonial endeavor of museums and within systems of oppression? Can Kim’s model be applied more broadly to other artists of the 1930s—for example, those involved in mural projects for the WPA, where anthropological typologies often show up? In a time of protests over police brutality, the entrenchment of white supremacy, and the call to decolonize museums, I understand Malvina Hoffman’s project as deeply problematic in its objectification of her subjects, real people she reduced to type in bronze.

Cite this article: Renée Ater, review of Race Experts: Sculpture, Anthropology, and the American Public in Malvina Hoffman’s Races of Mankind, by Linda Kim, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10840.

PDF: Ater, review of Race Experts

Notes

- Sir Arthur Keith, “Races of the World: A Gallery in Bronze,” New York Times, May 21, 1933. ↵

About the Author(s): Renée Ater is Provost Visiting Associate Professor at Brown University