Re-Reading American Photographs

Contributors

Erin Pauwels, “José María Mora and the Migrant Surround in 19th-Century American Portrait Photography”

Sarah Bassnett, “Undocumented Migration and Political Community in Susan Meiselas’s Crossings Photographs”

Josie Johnson, “A ‘Russianesque Camera Artist’: Margaret Bourke-White’s American-Soviet Photography”

Emily Burns,“Siŋté Máza (Iron Tail)’s Image Inversions: Lakȟóta Performance and Arts in Photography”

Wendy Red Star and Shannon Vittoria, “Apsáalooke Bacheeítuuk in Washington, DC: A Case Study in Re-Reading Nineteenth-Century Delegation Photography”

Lauren Johnson, “Reading and Re-Reading Ansel Adams’s My Camera in the National Parks”

Siobhan Angus, “Frank Speck in N’Daki Menan: Anthropological Photography in an Extractive Zone”

Elizabeth Hutchinson, “‘Photographic Weather: A Posthumanist Approach to Western Survey Photography”

Katherine Mintie, “Material Matters: The Transatlantic Trade in Photographic Materials during the Nineteenth Century”

Michelle Smiley, “Daguerreotypes and Humbugs: Pwan Ye-Koo, Racial Science, and the Circulation of the Ethnographic Image around 1850”

This In the Round asks what an American photograph is, and by implication, why this definition matters. We discursively return to Alan Trachtenberg’s Reading American Photographs of 1989 as a starting place for this interrogation both because of the central role the text continues to occupy in interpretations and teaching of US photographic history, and for its self-conscious emphasis on the temporally and culturally bound act of reading. As he writes: “Images become history, more than traces of a specific event in the past, when they are used to interpret the present in light of the past, when they are presented and received as explanatory accounts of collective reality.”1 Trachtenberg’s adroit interpretations demonstrate how photographs constructed US national meaning and, in turn, how interpretations of US history shape the photographic canon. This collection of essays celebrates his profound contributions to the field by exploring the questions that compel us now and inform our present collective reality, in reading American photographs roughly thirty years after the book’s publication. In 2020—following a four-year presidential administration defined by the violent use of racialized language, policies, and symbols intended to delimit national inclusion—these inquiries center not on the medium’s place in state formation, but instead on the contact, migration, and exchanges that have perpetually formed and reformed the Americas, moving toward an expanded geographical and temporal purview.

We contend, broadly speaking, that in scholarship, the word “American” continues to do too much work and not enough. Too much, in that it has come to signify an implicit host of perceptions shared by dominant groups—an (often white supremacist) set of cultural myths—and not enough, in that it typically refers to the United States and not to the Americas as a whole. This introduction articulates the changing historical construction of “American photographs” and puts forward a conception more rooted in multifaceted, fluid, often self-conscious, and at times cleaved senses of contemporary identity. First, we enumerate longstanding approaches to American photography and its historiography, with attention to the way that national identification has been variously formulated and deployed. We then develop a framework for understanding emerging strands of scholarship that employ a more expansive approach, offering new perspectives on well-known figures; uncovering under-recognized photographers, objects, and actors; and applying new heuristics and methodologies in reading American photographs.

Extending Trachtenberg’s marked interest in naming, and in recognition of our own subject positions as geographically and temporally bound individuals, we want to acknowledge that we write as Monica Bravo, a Latina art historian specializing in US interwar photography in a hemispheric context, now based in San Francisco, the unceded territory of the Ohlone and Coast Miwoks; and as Emily Voelker, a white art historian specializing in nineteenth-century photography and Native American art and representation, recently relocated to Greensboro, North Carolina, the site of meeting and exchange for many Indigenous peoples, especially the Keyauwee and Saura. We write for an informed Americanist audience, without presupposing deep familiarity with photographic history. We write in recognition of the fact that there is more work to be done to promote the contributions—past, present, and future—of Black, Indigenous, and people of color to the field (and beyond). We write against the backdrop of the global pandemic wrought by COVID-19, the protests engendered by the murder of George Floyd, devastating western wildfires precipitated by climate change, and a contested federal election. We write at this moment—something more we could not have predicted—in honor of Alan Trachtenberg, who passed away on August 18, 2020, and who helped inspire both of our scholarly journeys in photographic history. We write, finally, because we want to understand the urgent work of American photographs in our time.

American Photographs and Their Histories

Because of the unique character of photography’s invention—to which Louis Daguerre (1787–1851) of France and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) from England, among many others, claimed primacy—histories of photography until well into the twentieth century were remarkably focused on narratives of the medium’s inception as well as its technological development, lending them a decidedly nationalist bent.2 Without any plausible claim to the origin of photography, what role would America play in such histories, or, eventually, in writing its own?

Key moments and figures in US photography appear so frequently today that the field’s usual canon—as evinced by exhibitions, publications, syllabi, and even popular culture—can seem entirely natural rather than cultivated. Among the centrally featured historical events and photographers are those Trachtenberg analyzed in Reading American Photographs. Of course, in selecting these figures, Trachtenberg was engaging in his own methodological intervention in the scholarship, adapted from his background in American studies and literature, then steeped in New Criticism. By American photographs, he meant “photographs which take America as their subjects—photographs, that is, whose political motives lie close to the surface.”3 Taking seriously the role of photographs as texts within the larger study of American history, he focused on decoding their cultural work in shaping national mythologies, ethos, and social identity—his meaning of reading—in what he characterized as moments of conflict and change.4 Reading American Photographs is organized into five chapters; in it, Trachtenberg analyzes case studies of US photographers (all men) whom he argues simultaneously represented and constructed their historical moments: Mathew Brady (1822–1896) and antebellum society, Alexander Gardner (1821–1882) and the Civil War, survey photographers and western expansion, photographs of a changing New York by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and Lewis Hine (1874–1940), and photographs of the Great Depression by Walker Evans (1903–1975), the author’s colleague at Yale University.

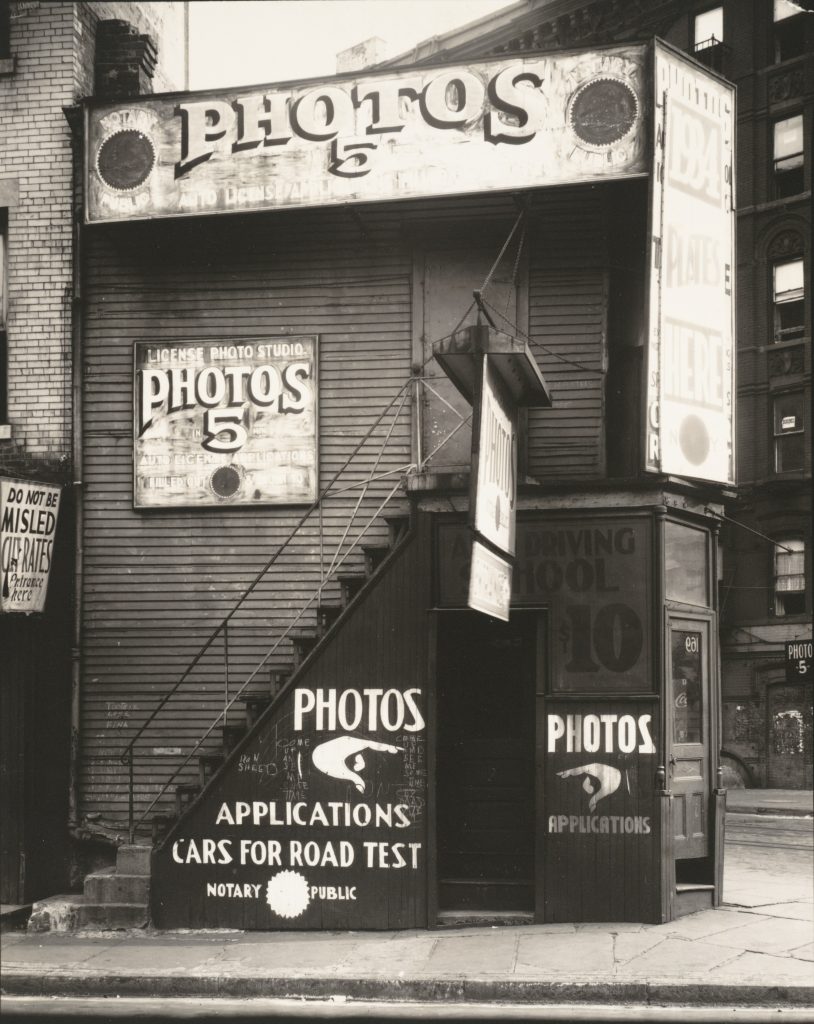

Trachtenberg’s book culminated in a discussion of Evans’s famed 1938 photobook American Photographs, the field’s most memorable invocation of the phrase. Through careful sequencing, the photographs conjure a nation in the process of becoming and, crucially, contribute to a percolating cultural nationalism then in formation. According to Evans’s construction, American photographs were imbued with a sensibility such as his: what was then called straight photography, perceived to correspond with the value of plain-speaking truthfulness associated with US identity. Despite this circumscribed conception, and the fact that a good number of the published photographs resulted from his government work with the Farm Security Administration in the South, three photographs Evans made in Havana, Cuba, found their way into American Photographs as well. Still, American photography has stubbornly tended to refer to photographs created in the United States, with an emphasis on key moments mythologized in the nation-building project, like those explored in Trachtenberg’s book. Its canon is primarily straight—photographs by Brady and Timothy O’Sullivan (1840–1882), and even vernacular images, have been ushered in as precedents to Evans’s work and that of other modernists. This discourse resonates with Lincoln Kirstein’s description of Evans’s photographs in his essay for the volume: “elevating the casual, the everyday and the literal into specific, permanent symbols.”5 Evans’s 1934 photograph of a license photo studio, in the style of Walt Whitman’s flowing poetic celebration of the everyday, elevates a prosaic structure used for one of photography’s most unsung vernacular forms—the identity picture—through a fine art photograph (fig. 1). In so doing, Evans knowingly comments on the proximity of the studio’s practice to his own. The result is a metadiscursive reflection on photography in America, the first in Evans’s thoughtful sequence in American Photographs, and the image chosen by Trachtenberg for the cover of Reading American Photographs.

Several scholars have expanded upon the ways in which American histories of photography were formalized, including Anthony W. Lee, who characterizes those written in the nineteenth century as mishmashes of “aesthetic, scientific, technical, and commercial interests,” that often failed to cohere, sometimes combining with heroic biography.6 François Brunet credits two men, Beaumont Newhall and Robert Taft, with introducing distinct new approaches to the writing of photographic history in the 1930s, contemporaneous with Evans’s photobook.7 The Museum of Modern Art exhibition and catalogue Photography, 1839–1937, by curator Newhall, privileges modernist aesthetics even as it interweaves technical developments in its teleology. Newhall’s 1937 volume—revised and renamed through various editions—remains a standard textbook today, contrasting with the nearly forgotten but then-popular Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839–1889, published in 1938 by his contemporary, Taft.8 A professor of chemistry at the University of Kansas, Taft labeled his book a social history for its emphasis on photographs that either recorded or intervened in historical events. However, as Doug Nickel indicates, the book functioned primarily through a mechanism of technological determinism, in a manner quite distinct from the social history of photography as it materialized in the 1970s.9 These divergent models of historiography—one aesthetic, emerging from the context of the art museum; the other avowedly social, arising from an academic—broadened the history of photography’s disciplinary purview, while also continuing to actively shape canonized moments of American photography.

By the 1970s, coinciding with the beginnings of the fine art market for photography, the medium’s history definitively emerged as an academic pursuit across many different disciplines: in art history, certainly, just as the field was engaging with its own identity crisis, as well as in American studies, English, and history—and many more today, including other area studies, film and media studies, and history of science. Trachtenberg’s text emerged in the wake of these developments, groundbreaking within interdisciplinary American studies for its emphasis on photographs not merely as illustrations but as indispensable agents in the creation of nation. Indeed, so complete was the US intervention in photographic history that by the late 1980s, it was possible to claim that “even though Americans did not invent photography they should have.”10 Photographic history had, apparently, become a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Today, no one discipline or nation owns the history of photography, let alone that of American photography. Our aim here is to highlight a critical shift over the last several decades regarding histories and theories of photography, merging them with the scholarly turns that have transformed the field of American art.

Networks/Materials/Meanings

Informed by the transnational turn in the history of American art and visual culture over at least the last two decades, as well as interdisciplinary photographic studies during the same period, we read American photographs beyond issues of representation and constructs of national teleology alone. Taking a longer view, this approach locates photographic practices within the histories of contact, movement, and encounter out of which the cultures of the Americas continually emerge. Our interests build on the work of many other Americanists—such as Jennifer Roberts, Jennifer Van Horn, Jessica Horton, and ShiPu Wang, to name a few—also charting networks instead of monolithic state formation in their crafting of art and material culture histories. These approaches at once exceed and puncture imaginations of nation.11

Photographic history and theory across disciplines has similarly moved toward analysis of links and webs of connection, which has proven a particularly rich framework given the reproducibility and portability that characterize a majority of the medium’s objects of study.12 Tanya Sheehan’s edited volume Photography and Migration (2018) and Lee’s bold single-photograph study A Shoemaker’s Story (2008) are both especially germane here in their focus on diasporic migration, circulation, and identity.13 Other recent edited volumes squarely address some of the questions we are likewise pursuing, including Bettina Gockel’s anthology of global histories of American photography, and Justin Carville and Sigrid Lien’s forthcoming collection focused on migration and cultural encounters in America.14 This In the Round draws upon these intellectual currents to specifically examine how we classify and interpret American photographs in recognition of the shifting (and constructed) borders—both geographic and political—and changing parameters of inclusion in the Americas.

Central to our intervention is an interrogation of photography’s entanglement in the ongoing and unfinished project of colonialism that defines the Americas by way of a settler colonial framework. Locating the medium’s place in these contact histories facilitates multi-vocal readings that eclipse visual interpretation of these objects solely as pictures implicated in the pursuit of various nation-building efforts. Indeed, many of the case studies that the authors cite did in fact once function in such a way. However, as Jennifer Bajorek notes, photographic theories “centered on its European and North American histories have long sought to explain the singularity of the photographic image in connection with the problem of representation . . . on ‘fixing’ an image of the world.”15 Examining these photographic objects while attuned to settler colonial histories opens analysis to other facets, iterations, lives. A settler colonial framework incorporates and centers Indigenous presences, experiences, and meanings in ongoing interaction with European and, later, Anglo-American colonizers since contact.16 While scholars of photography in area studies such as Native American/Indigenous studies and Latin American studies often utilize this methodology as a matter of course, the discipline of art history has been slow to adopt it. Part of this belatedness undoubtedly stems from the central place of settler institutions and discourses, such as the museum, collection, archive, and connoisseurship, to our discipline. In contrast, photographic history and theory from the context of Black and African American studies—by scholars such as Deborah Willis, Shawn Michelle Smith, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Tina Campt, and Sheehan—has more fully confronted histories of diaspora, violence, and shared experience beyond place.17 This rich vein of scholarship foregrounds the historic role of global encounter and asymmetries of power that likewise characterize each intimate, interpersonal photographic event, albeit in miniature and often with a lesser degree of conflict.

Similarly, while internationalization and global contexts for US art history have emerged as among the most significant trends in the discipline, academic institutions and museums have only recently established positions, departments, and concentrations dedicated to art of the Americas beyond the ancient context. Concurrently, American art specialists are extending course offerings, publications, and galleries to include more expansive ideas of the field. Considerations of colonial legacies and thematic concerns unique to the hemispheric, modern-era Americas remain rare, with notable exceptions such as the edited volume The Social and the Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere of 2006; the opening of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Art of the Americas Wing in 2010; the Terra Foundation’s traveling exhibition Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic of 2015–16; the inaugural Getty-led initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA of 2017–18; and recent books by scholars primarily of Latin America, including Claire Fox, Edward Sullivan, and Niko Vicario.18 Few scholars approach both the hemispheric context and the history of photography, making this a particularly fruitful avenue for further scholarly investigations of American photography.19

While we probe photographs as embodiments of an often intercultural coming together, their fabrication also incarnates a material merging from disparate worlds, as recent essays by Laura Turner Igoe and Robin Kelsey for the 2018 exhibition catalogue Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment explore.20 As multiple “Re-Reading American Photographs” contributors delineate, the production of photographs has historically relied on the convergence of tactile components from across the globe—silver from Bolivia, papers from France, and lenses from Germany, to name a few examples featured here. This comingling then comprises the matrix for representation of an “American” subject, or creation by an “American” maker, complicating our disciplinary modes of assigning national authorship. Along with the union of these diverse national products, photographs make manifest the interaction between the maker and the places, spaces, and forces—sometimes outside of their control—that impinge on and, as contributor Elizabeth Hutchinson argues, even delimit the resultant outcomes and possibilities of production. This amalgam of sources and currents that merge in the photograph then extends to another condition of materiality: the material circulation and appropriation of the work in new contexts as it travels in space and time. An established body of scholarship examines this aspect of photographic materiality, investigating how the tangible, physical aspects of a photograph perform the image itself in specific, relational contexts.21

US western survey photography of the post-Civil War period serves as an instructive case study for epistemological readings of American photographs. Trachtenberg’s chapter treating this material, focused primarily on O’Sullivan’s work for the King Survey, weaves analysis based on the intertwined politics of naming, viewing, and possessing in processes of imperialist expansion. As he writes, “The name lays claim to the view. By the same token, a photographic view attaches a possessable image to a place name. A named view is one that has been seen, known, and thereby already possessed.”22 His interpretation deftly explores the work of these photographs—as representations across domestic contexts—in the nation-building project. But what were the other names and meanings of these spaces in lived experiences outside the Euro-American settler framework?23 Situating the works in the local and contact histories that long predate this moment of encounter centers relationships to both place and object that exceed state formations. As contributors Shannon Vittoria and Wendy Red Star demonstrate, Indigenous communities bring their own readings, memories, and understandings of sovereignty to colonial survey photographs; such interpretations are an equal part of their multifaceted meanings.

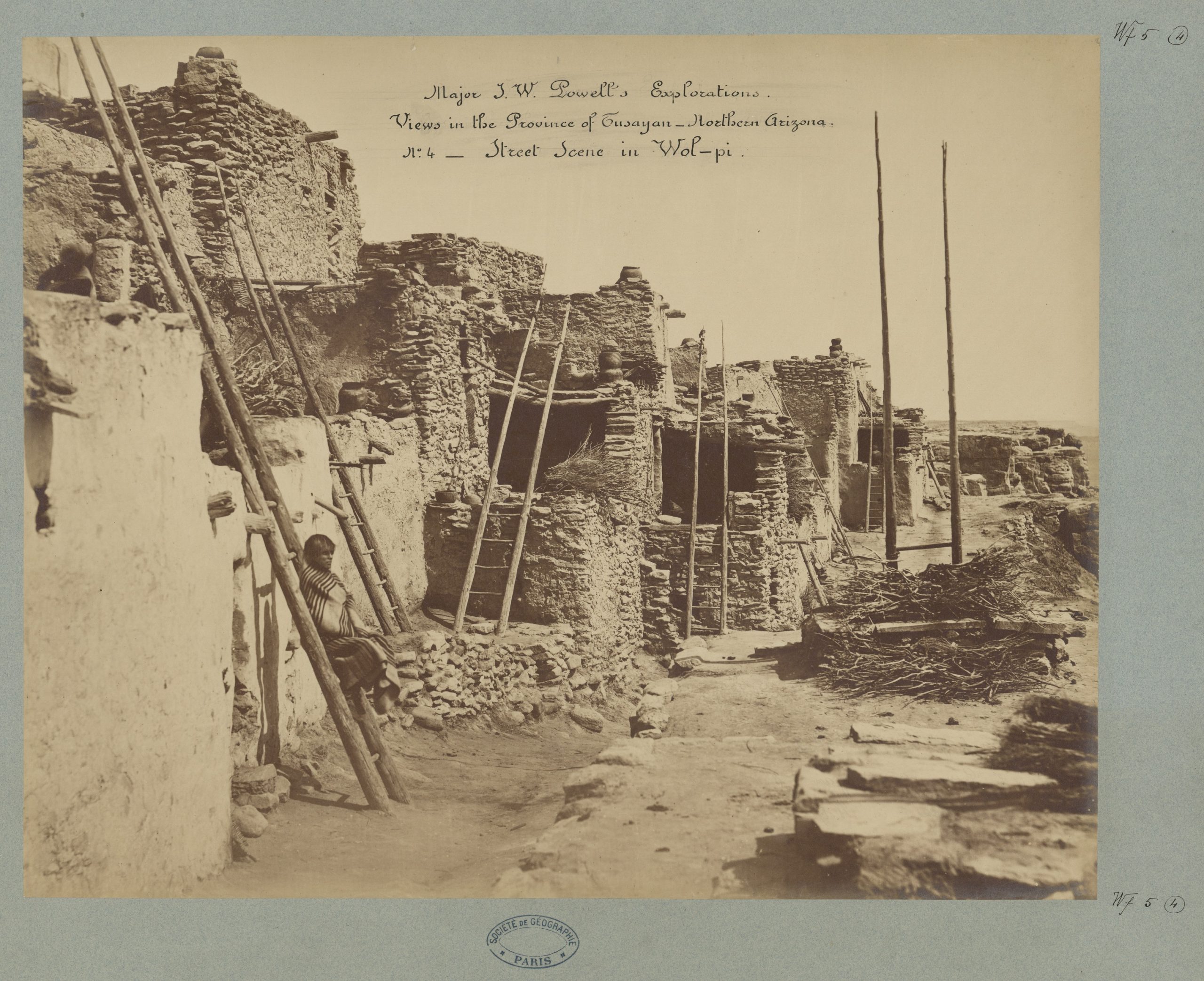

Furthermore, western survey photography not only functioned in a national arena to fuel expansion but circulated on a global scale, where it entered into entirely new political and social formations. John Wesley Powell and Ferdinand V. Hayden, the two survey leaders working under the Interior Department, disseminated the work of their respective photographers, John K. Hillers (1843–1925) and William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), on a vast international scale. Powell, for example, included a group of nine exhibition prints by Hillers of First and Second Mesa Hopi Villages at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876 that were then gifted to the Société de Géographie in Paris the following year (fig. 2).24 Institutions in locations as far ranging as New South Wales and Bermuda requested similar sets of photographs after viewing them at the Centennial.25 What were the meanings of these objects, we might ask, as they performed in new national contexts during a period of aggressive and expansive imperialism? Notably, many of the western survey photographers—including Hillers and O’Sullivan—now celebrated for their work on nation-building projects during a period of unification, were likewise asked to perform as immigrants to the United States. They were likely always treated with recognition of such difference and forced to navigate shifting identifications in a period marked by the aggressive mapping and engineering of the United States’ diverse social body, a practice that Erin Pauwels’s contribution deftly explores.

Re: Reading American Photographs, and Developing Lines of Inquiry

Reading American Photographs is a touchstone for this special section of In the Round. We—as editors and contributors—test our ideas against Trachtenberg’s, venturing into the spaces opened up by our intellectual predecessors. In this sense, we are not simply reading Reading American Photographs again, as valuable as that exercise proves. Rather, we continue to grapple with the sociopolitical realities and consequences of state formation as we conceptualize “American photographs” anew, through the multifaceted, fluid, and now often contested conception of national identity itself. In so doing, our project is informed by more recent developments in American art and the history of photography, as well as the urgent concerns of our time. Collectively, the following essays model a path forward for American photography that is geographically wider and temporally longer, taking into account the pre-1839 social relations, cultures, and exchanges in which the medium intervenes.

While building toward an ambitious new scope, many of the essays are relatively modest in their aspirations. As opposed to defining moments, they tend to look at the interstices between grand historical events. With few exceptions, the names of the photographers are not well known, the bodies of work rarely celebrated. These articles represent a marriage of the history of photography’s macro pretensions, usually aimed at canon formation and efforts to define photography’s ontology, with the kind of micro investigation necessary to study our objects. The path to a new understanding of American photography, it turns out, is through close reading of American photographs.

The contributors represent a range of backgrounds, from creative practice to conservation and museums to academia, and are at various stages of their careers. Inevitably, certain paper titles will pique the reader’s interest, and there is no prescribed navigation through the articles. While each paper is unique, several sub-themes emerge.

Transnationalism is one of the most apparent threads. Two essays address migration in the hemispheric context, focusing especially on borders as a tool of state partitioning. Erin Pauwels explores José María Mora’s contributions to nineteenth-century American portrait photography in light of his exile from Cuba (a status overlooked in Taft’s Photography and the American Scene) and what she terms a “migrant surround.” Jumping ahead a century later, Sarah Bassnett’s essay on Susan Meiselas’s Crossings series from the late 1980s investigates the status of the US-Mexico border through Jacques Derrida’s framework of the “structuring enemy.” Josie Johnson reconsiders documentary photographer Margaret Bourke-White’s early 1930s Soviet images, which display both US and Russian photographic influences, and engendered a confused response to match. These papers put pressure on the geographic limits of what was heretofore considered American photography.

Several essays deal with questions of sovereignty and settler colonialism within the present-day United States, two of them via portraiture and a third through landscape. Emily Burns compares three sets of photographs made over the course of twelve years depicting Siŋté Máza (Iron Tail), a Lakȟóta Wild West performer. In so doing, she probes the gap between portrait and type, identity and persona, across racial lines. Wendy Red Star and Shannon Vittoria’s collaborative essay reads Charles Milton Bell’s 1880 photographs of a delegation of six Apsáalooke leaders against received interpretations of such images as ethnographic stereotypes. Their analysis draws on Red Star’s contemporary photographic practice, local Apsáalooke knowledge and memory, and the pair’s recent exhibition, Artistic Encounters with Indigenous America, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Finally, Lauren (Ally) Johnson’s article revises understandings of Ansel Adams’s My Camera in the National Parks (1950) as a straightforward conservation text. Instead, informed by Indigenous critiques, Johnson reveals the project’s imbrication with expansionist politics in its inclusion of Hawaiian subjects, just as the United States pushed for the islands’ statehood.

An emphasis on photographic materiality—as it affected labor practices and the circulation of objects—unites four of the papers. Bridging themes of sovereignty—now within a hemispheric context—with an emphasis on physical materials, Siobhan Angus demonstrates how the logic of extraction characterized transnational entanglements between labor, capital, and metals, through a close reading of anthropologist Frank Speck’s early twentieth-century album of a Temagami community in northern Ontario. Elizabeth Hutchinson explores the localized material conditions—air, water, light, as well as varying access to substrates and chemicals—that set a physical limit to survey photography. Drawing on robust technical guidance from nineteenth-century European and US publications that advised photographers on responding to distinctive environmental conditions, Hutchinson considers the technical aspects of American photography, and not solely their representations. Two papers focus on photographic circulation and exchange: Katherine Mintie uses examples from The Philadelphia Photographer that highlight US-based makers but also materials manufactured abroad. Such materials seemingly exceed the idea of an American photograph, when in actuality they speak to a robust transatlantic trade in the early photographic industry. Michelle Smiley brings attention to a network of racial scientists centered on Louis Agassiz, who used the US postal service—another timely reference—to mail each other daguerreotypes as a means of sharing ethnographic “evidence” for their claims. Smiley’s essay focuses on a cased image of Miss Pwan-Ye-Koo, exhibited as part of P. T. Barnum’s Chinese Museum; the circulation of her physical body was extended to that of her photographed visage.

These exceptional examples of recent scholarship on American photographs represent a simultaneously broader but more nuanced and multifaceted understanding of the phrase for our context today. It is our hope that they will be read and re-read alongside canonical texts in the field, and that they stand together as a tribute to Trachtenberg’s legacy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Douglas Nickel and Anthony W. Lee for their insightful, generous comments on a previous draft of this essay, to Paula Kupfer for her suggestions regarding recent hemispheric scholarship, and to Panorama’s editorial team for their enthusiasm for the project and expert guidance through to its final form.

Cite this article: Monica Bravo and Emily Voelker, “Re-Reading American Photographs,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10844.

PDF: Bravo and Voelker, Re-Reading American Photographs

Notes

- Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), 6. ↵

- Doug Nickel, “History of Photography: The State of Research,” Art Bulletin 83, no. 3 (September 2001): 548–49. ↵

- Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs, xv. ↵

- Thank you to Doug Nickel for pushing us to think more carefully about Trachtenberg’s use of the term “reading” in relationship to his training and photographic theory—especially as informed by semiotics. ↵

- Lincoln Kirstein, “Photographs of America: Walker Evans,” in Walker Evans: American Photographs, 75th anniv. ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 197. ↵

- Anthony W. Lee, “American Histories of Photography,” Commentaries, American Art 21, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 2–9. ↵

- François Brunet, “’An American Sun Shines Brighter,’ or, Photography Was (Not) Invented in the United States,” in Photography and its Origins, ed. Tanya Sheehan and Andrés Mario Zervigón (New York; London: Routledge, 2015), 131–44; François Brunet, “Robert Taft: Historian of Photography as a Mass Medium,” American Art 27, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 25–32; François Brunet, “Robert Taft’s Photographic History of America (Photography and the American Scene, 1938),” E-rea 8, no. 3 (2011), https://doi.org/10.4000/erea.1777. ↵

- Robert Taft, Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839–1889 (New York: Macmillan, 1938). And, Newhall’s own sanctioning of the project, according to François Brunet in “Robert Taft in Beaumont Newhall’s Shadow,” Etudes photographique, no. 30 (2012), https://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3481. ↵

- Douglas Nickel, “The Social History of Photography,” in The Handbook of Photography Studies, ed. Gil Pasternak (London: Routledge, 2020), 48. ↵

- François Brunet references this quote, credited to Régis Duran and based on a statement by Lewis Baltz, in Brunet, “’An American Sun Shines Brighter,’” 135. ↵

- See Jennifer Roberts, Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Jennifer Van Horn, The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Jessica Horton, Art for an Undivided Earth: The American Indian Movement Generation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); ShiPu Wang, The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); and Amelia Goerlitz, ed., “Mapping a Transnational American Art History,” American Art 31, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 62–64. ↵

- Nadya Bair, The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020). The College Art Association (CAA) affiliated society Photography Network will sponsor a panel at the 2021 conference titled “Photographic Networks,” co-chaired by Catherine Zuromskis and Kate Palmer Albers. Formalized, if amateur, networks such as camera clubs in Brazil, California, and Japan have also emerged as sites of academic and museological interest. ↵

- Tanya Sheehan, ed., Photography and Migration (New York: Routledge, 2018); and Anthony W. Lee, A Shoemaker’s Story: Being Chiefly about French Canadian Immigrants, Enterprising Photographers, Rascal Yankees, and Chinese Cobblers in a Nineteenth-Century Factory Town (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008). Both scholars have led the expansion of histories of American photography, and Lee’s text relates to his larger foundational work on immigrant communities and launching of the series Defining Moments in American Photography with University of California Press. ↵

- Bettina Gockel, ed., American Photography: Local and Global Contexts (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2012). Justin Carville and Sigrid Lien co-organized a 2018 workshop on Photography, Migration and Cultural Encounters in America in Dún Laoghaire, Ireland, that formed the basis for Justin Carville and Sigrid Lien, eds., Contact Zones: Photography, Migration and Cultural Encounters in the U.S. (Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press, 2020). ↵

- Jennifer Bajorek, Unfixed: Photography and Decolonial Imagination in West Africa (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 18. ↵

- See Frederick E. Hoxie, “Retrieving the Red Continent: Settler Colonialism and the History of American Indians in the U.S.,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31, no. 6 (2008): 1153–67. ↵

- See Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002); Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002); Shawn Michelle Smith, Photography on the Color Line: W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, ed., “Vision & Justice,” special issue, Aperture 223 (Spring 2016); Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); and Tanya Sheehan, Study in Black and White: Photography, Race, Humor (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018). ↵

- See Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg, eds., The Social and the Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006); regarding the MFA, Boston, see “Art of the Americas,” on the museum website, accessed September 19, 2020, https://www.mfa.org/collections/art-americas; Peter John Brownlee, Valéria Piccoli, and Georgiana Uhlyarik, eds, Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015); regarding Pacific Standard Time, see the initiative’s website, accessed September 19, 2020, http://www.pacificstandardtime.org/lala/index.html; Claire F. Fox, Making Art Panamerican: Cultural Policy and the Cold War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013); Edward J. Sullivan, Making the Americas Modern: Hemispheric Art 1910–1960 (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2018); and Niko Vicario, Hemispheric Integration: Materiality, Mobility, and the Making of Latin American Art (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020). ↵

- Exceptions include Natalia Brizuela and Jodi Roberts, The Matter of Photography in the Americas (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018); and Monica Bravo, Greater American Camera: Making Modernism in Mexico (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021). ↵

- Laura Turner Igoe, “Creative Matter: Tracing the Environmental Context of Materials in American Art,” in Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment, eds. Karl Kusserow and Alan C. Braddock (Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 2018), 140–69; Robin Kelsey, “Photography and the Ecological Imagination,” in Kusserow and Braddock, Nature’s Nation, 394–405. ↵

- On this trend, see especially the work of Elizabeth Edwards, including Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, eds., Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images (London: Routledge, 2004). ↵

- Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs, 125. ↵

- See Martin A. Berger, “Overexposed: Whiteness and the Landscape Photography of Carleton Watkins,” Art Journal 26, no. 1 (2003): 3–23. ↵

- For announcement of the arrival of these works to the society, see Bulletin de la Société de géographie, Vie série 13 (January 17, 1877): 213. François Brunet traces the transnational photographic gift culture of the western American surveys, particularly, to French institutions, in Bronwyn Griffith and François Brunet, eds., Images of the West: Survey Photography in French Collections, 1860–1880 (Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2007). ↵

- NARA Microfilm 156, Letters Received, nos. 185 and 190. ↵

About the Author(s): Monica Bravo is Assistant Professor in the History of Art and Visual Culture at California College of the Arts. Emily Voelker is Assistant Professor of Art History at the College of Visual and Performing Arts, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro