The Republic of the Spirit: Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life in Two Novels by Edith Wharton

PDF: Routhier, Republic of the Spirit

Early in Edith Wharton’s breakout novel, The House of Mirth (1905), a younger version of the protagonist Lily Bart muses critically about poor relations who, among other defects, “inhabited dingy houses with engravings from Cole’s Voyage of Life on the drawing-room walls” (29).1 Scholars of both Edith Wharton (1862–1937) and the painter Thomas Cole (1801–1848) have noted this allusion and generally assessed it as a foil for Lily’s—and, by extension, Wharton’s—more modern and upscale tastes in turn-of-the-century New York.2 But thus far no one who has discussed this tantalizing nugget of ekphrasis has dealt significantly with the artwork itself: Cole’s The Voyage of Life, a series of four allegorical paintings completed in 1840, and the engravings made after it, which were published in the 1850s (figs. 1, 2). Nor have scholars noted that Wharton makes a similar reference to “large dark steel-engravings of Cole’s ‘Voyage of Life’” in another work of fiction: The Old Maid, one of four novellas published together as Old New York in 1924 (24).3 Delving more deeply into the complex history of Cole’s work allows for a richer understanding of how Wharton, her protagonists, and her readers would have understood it within the context of the New York society they inhabited and its power to nurture, tempt, and ultimately thwart the dreams of youth.

The Voyage of Life: Beginnings

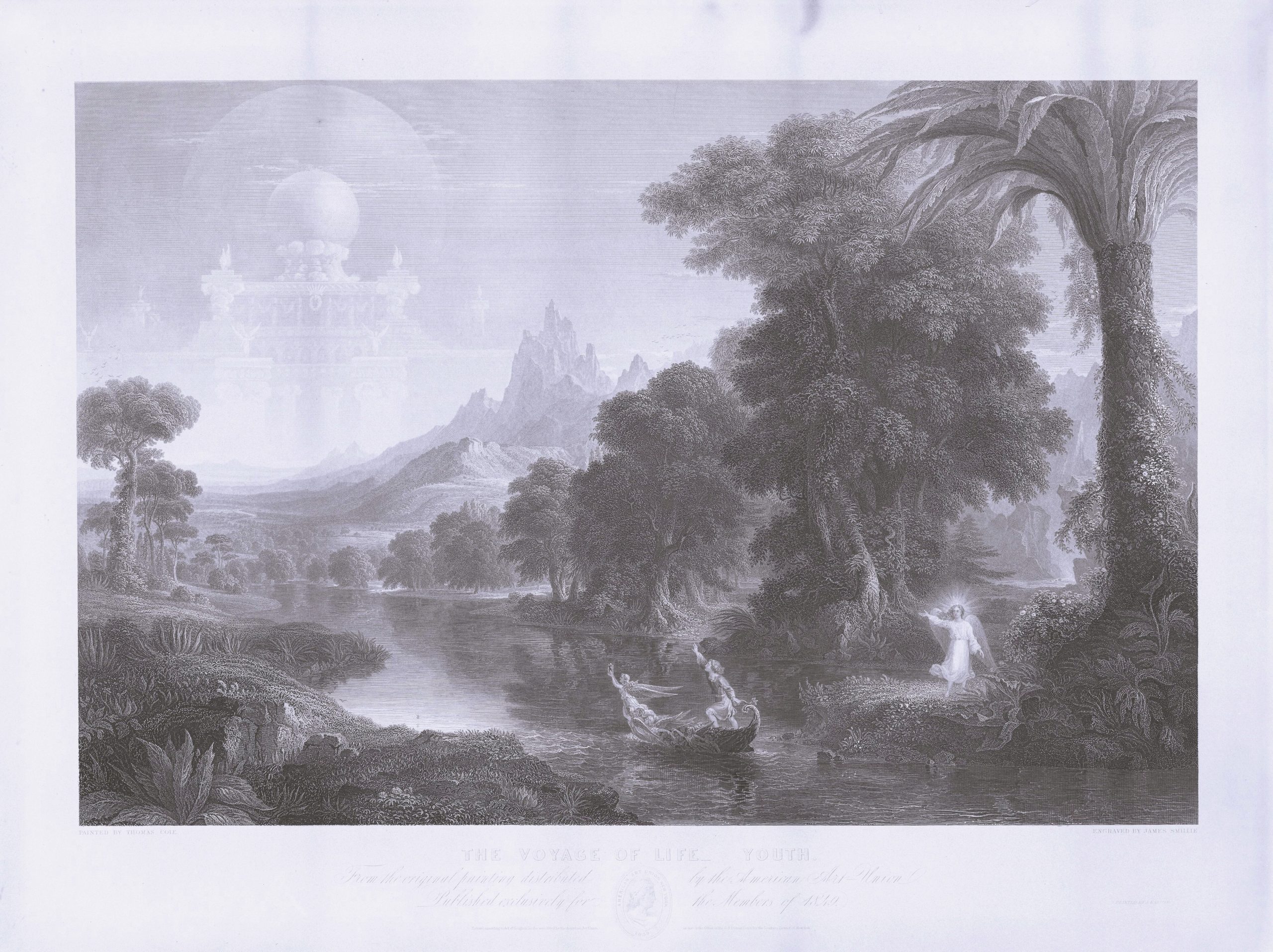

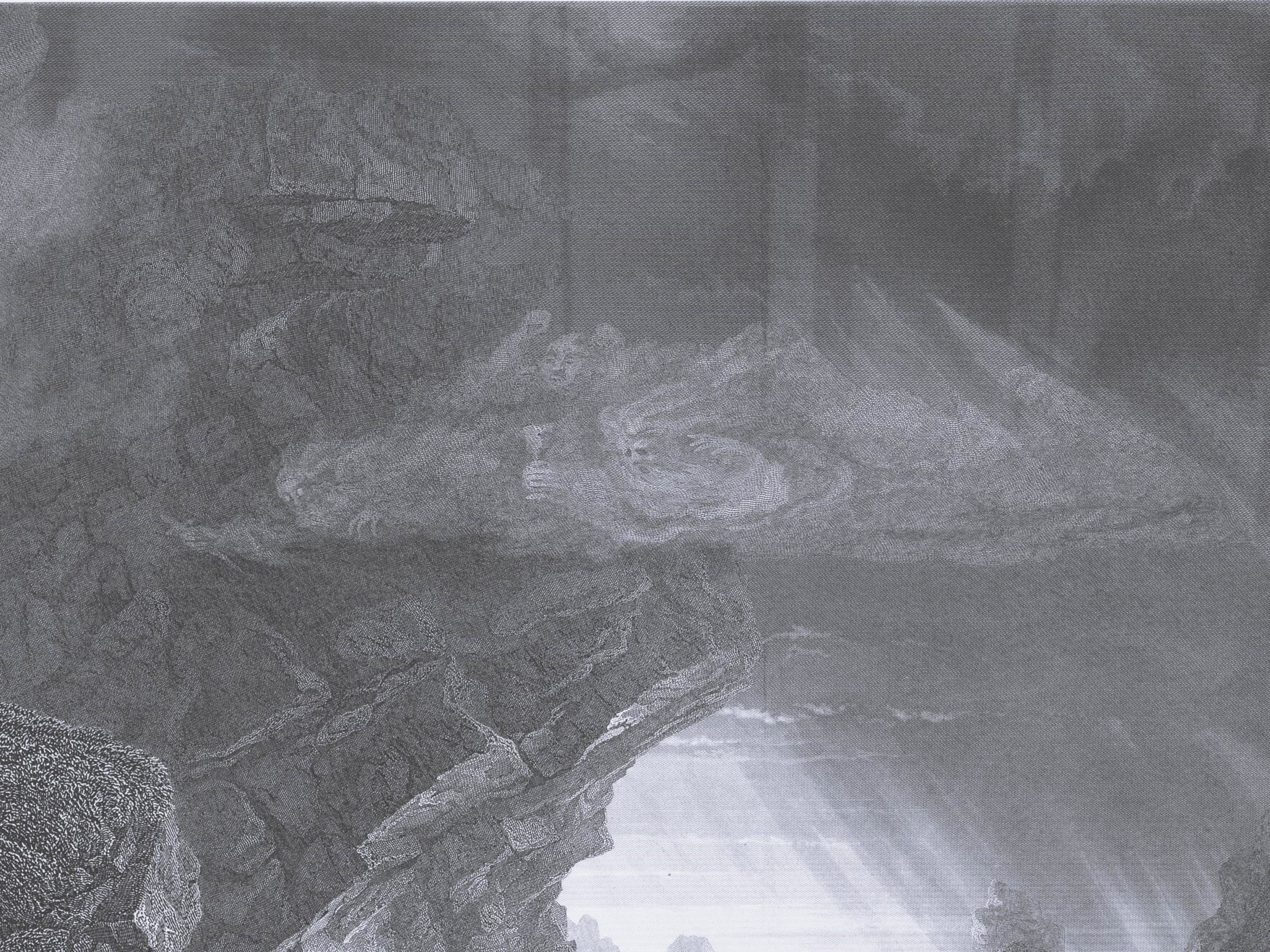

Envisioned and developed by Cole over a period of years, The Voyage of Life was completed as a commission for New York banker Samuel Ward in 1840. The four massive paintings—each some fifty-two inches high by seventy-eight inches wide—titled Childhood, Youth, Manhood, and Old Age, show a single traveler journeying on a golden riverboat through a landscape that changes from meadow to mountain, spring to winter, dawn to dark, all as the voyager grows older. In Childhood, the boat and its passenger, guided by an angel, emerge from a dark, womb-like cave into a sunlit landscape filled with flowers, with a velvety green meadow, fantastic crystalline mountains, and a blue sky beyond. In Youth, the traveler has reached that magical meadow and steers the boat toward a vision of a domed castle in the sky as the angel bids him farewell from the riverbank. In Manhood, the scene is suddenly different and terrifying: the once-lofty trees are now blasted and twisted stumps, and looming crags of rock predominate as the traveler’s boat, now rudderless, bears him along the rapids. In Old Age, the angel, once again at the traveler’s side, points from the still dark waters where the boat is becalmed toward an opening in the clouds, suffused in white light. This last scene is almost stripped of color, anticipating the series’ later manifestation as a set of black-and-white prints.

The Voyage of Life has various precedents in Western art and literature, going back to Ovid’s and Hesius’s concepts of the “Ages of Man,” which describe the development and decline of civilization.4 In the Renaissance, artists conflated these ideas with the physical ages of man, from infancy to old age, as seen in Titian’s canvas The Three Ages of Man (c. 1512–14; National Gallery of Scotland) and Giorgio Vasari’s allegory of the Four Ages of Man from the ceiling of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence (1560s).5 The motif of the seasons of the year, also anchored in antiquity, was a related, parallel development in the fine arts, gaining particular currency in courtly settings and then neatly adapting to the more secular and scientific interests fostered by the Enlightenment.6 In nineteenth-century Europe and the United States, the seasons became the frequent subject of numerous four-part series—in a variety of media—that nevertheless retain the anthropomorphic contexts of the ancient poets and Renaissance masters.

Cole drew on these roots for The Voyage of Life but was also inspired, in part, by the specifically Christian message behind The Pilgrim’s Progress. John Bunyan’s allegorical proto-novel of 1678, which was wildly popular in the nineteenth-century United States, details a journey through a fictional landscape from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City. Echoes of Bunyan’s imagery are evident not only in The Voyage of Life but also in Cole’s own writing about the series, discussed further below. These intertwining aesthetic and literary associations must have made Cole’s series an appealing point of reference for Wharton: its central motif of an aging traveler’s journey through a moralized, ever-changing landscape has clear connections to the plots, imagery, and thematic throughlines of her New York novels.

In The House of Mirth, set in late Gilded Age New York, the orphaned Lily Bart struggles to stay afloat in the treacherous waters of the elite society into which she was born. She has no money of her own, so her beauty and charm are her key assets, yet she constantly shrinks from trading on them in a way that will ensure her security. In the end, she becomes a social outcast, poverty-stricken and addicted to the sleeping drug that causes her death. In The Old Maid, which takes place some fifty years earlier, Delia Ralston is, by contrast, an advantageously married mother, secure in her station in one of the “best” families of old New York. But when her cousin Charlotte (the “old maid” of the title) confesses that in her youth she succumbed to passion and bore a child out of wedlock, Delia begins to feel oppressed by her own static situation. Out of envy and frustration, she steadily usurps Charlotte’s relationship with her daughter, Tina, ultimately adopting the child and burying the secret of her parentage forever. Both stories have in common the idea of promising young lives blown off course by risky ventures gone awry, an idea that Wharton’s references to The Voyage of Life introduce within the first chapters of each novel.

A Dazzling Debut7

As art historian Alan Wallach points out, Cole intended The Voyage of Life to be a work of popular art—just as Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress was—with universalizing themes that would be understandable and readily familiar to the broad public.8 In this endeavor, the series succeeded spectacularly, despite some early hiccups. The patron, Samuel Ward, died before the paintings were completed, and at one point his family asked to be released from the agreement with Cole.9 They then wanted to prevent Cole from exhibiting the series before he turned it over to them, which would have been a significant hardship since he planned to monetize its early display through admission fees.10 Cole circumvented this restriction initially by allowing the public to visit his studio rooms at the National Academy of Design’s new building on the corner of Leonard Street and Broadway, free of charge, to see the paintings as he was still applying their finishing touches. Ward’s son eventually allowed Cole to charge admission.11

Although the series’ time on public view was relatively brief, it was memorable, aided by the initially free open admission, positive reviews, and Cole’s own expressive yet lucid description of the works’ symbolism, which he made available to visitors in printed form.12 While the series was physically the property of a single wealthy family, Cole’s leaflet speaks to his ambition that it should, in some moral sense, belong to the public as well. Contrast this to the rarefied and bespoke way in which Wharton’s characters experience art in her New York novels—at, for instance, the famous tableaux vivants scene in The House of Mirth, where Lily and other society women in elaborate costumes reenact famous paintings for an elite audience. It follows that, in Wharton’s fictional world, those whose appreciation of art hinged on such exclusivity should look askance at Cole’s popular and accessible series.

The history of most major nineteenth-century American paintings might normally end or at least pause here, with their disappearance into a robber baron’s home before being acquired by a public art institution decades later. But The Voyage of Life led several lives, including a complex history of reproduction that includes the prints Wharton mentions. First, however, Cole himself reproduced the series, in oil, at full scale, during a sojourn in Rome in 1841–42. Although he did not manage to sell these copies in Rome, and the critical response once he brought them back stateside was mixed—some critics thought them hastily done13—they traveled broadly, and profitably, throughout the Eastern seaboard for several years before Cole sold them to a Cincinnati collector in 1846.

Cole had not yet reached old age in his own voyage of life, so no one anticipated that the beloved and respected artist—widely revered in his own time as the founder of the first truly American school of painting—would be dead in a little over a year, in February 1848. Immediately upon the news of his passing, plans developed to memorialize him in a major exhibition to be hosted at the “Free Gallery” of the American Art-Union (AAU) on lower Broadway at Broome Street in New York.14 The Voyage of Life comprised four of the eighty-three Cole paintings on view there, once again presented free of charge to a broad public—some five hundred thousand visitors, by one estimate.15 That an audience larger than the entire population of New York City at the time had unfettered access to nearly the entirety of his artistic output underscored Cole’s role as an artist for the people and not just for the elite.16

On the Rocks: The American Art-Union

Like Cole, the AAU was committed to bringing art to the masses in a literal and material way. Founded in 1839 and directly in competition with the National Academy of Design (NAD), it held an annual exhibition at which the works on view were available for members of the public to acquire. But whereas the NAD brokered traditional consignment sales, like an art gallery, the AAU purchased the artworks for its exhibition outright and then used a membership lottery system for distribution: each annual membership fee purchased a single chance to win a work of art from the show. Probably buoyed by the success of Cole’s memorial exhibition, the AAU made the calculated risk to purchase, directly from the Wards, Cole’s original The Voyage of Life for its December 1848 annual show and lottery. As scholars have observed, AAU membership swelled exponentially in the months leading up to the 1848 lottery as new members bought their five-dollar chances to win Cole’s famed and valuable series. In the end, it went to one of those new members, the owner of a small newspaper in Binghamton, New York, who within a few months turned around and sold it to one Rev. Gorham D. Abbott of the Spingler Institute, a school for young women in Union Square, for an astounding return on his modest investment.17

The AAU lottery had worked exactly the way that it was designed to, and yet the Voyage of Life transaction is emblematic of criticisms levied at the institution that were reaching a head as the 1840s drew to a close.18 It was all very well and good to make art ownership accessible to the masses, critics complained, but did it serve the AAU’s lofty mission if the masses were more interested in financial gamesmanship than the art? Further, the AAU was also criticized for lowballing the artists it patronized and, Cole’s series notwithstanding, for depressing the art market by primarily acquiring and distributing smaller-scale, more anodyne work—landscapes and genre scenes rather than complicated historical or allegorical compositions—of the type that would fit comfortably into middle-class parlors; these works were more likely to stimulate ticket sales. The AAU was also criticized for its unsustainable financial model: the strength of the show and lottery depended on the strength of ticket sales, and vice versa, resulting in what scholar Joy Sperling terms a kind of “financial game of chicken,” in which both potential members and AAU officers waited to see who would take the risk first.19 While this worked out in the AAU’s favor brilliantly in 1848, they were unable to sustain the peak membership that The Voyage of Life brought in, and membership decreased dramatically thereafter. In the end, the acquisition and distribution of Cole’s series sounded the first tones of a death knell for the AAU, which struggled along until, in 1852, the New York Supreme Court ruled that it was an illegal lottery and forced it to cease operations and dissolve its assets.

The financial risk-taking of the AAU, coupled with its painful denouement and its ultimate fate, have parallels to Lily Bart’s story: over the course of two years, she is undone, in part, by a financial scheme in which she is led to believe she is risking her own money but is actually accepting gifts from a married man, Gus Trenor, who expects repayment of another kind. The novel’s themes of economics and art—Wharton’s overriding metaphor of Lily as a work of art is deeply connected to ideas of markets, commodities, investments, and depreciation20—are undergirded in its earliest pages by this allusion to a well-known story of art, risk, and loss. In the final pages of the book, as Lily’s own voyage of life comes to an end, one of her last acts is to dissolve her own assets, taking a sudden windfall that could have saved her from abject poverty and using it instead to pay back her intolerable debt to Gus.

Afterlife: The Engravings

It is significant that Wharton’s point of reference is neither of the painted versions of The Voyage of Life but rather the set of engravings. Before Cole’s monumental series was raffled off, the AAU sent it to the home of artist James Smillie on 12th Street to be copied for the purposes of producing a suite of engravings.21 Another membership benefit of the AAU and part of its mission to bring art to the masses was the annual production and distribution to its members of a high-quality engraving of a single work of art; in 1849, that work was the Youth canvas of The Voyage of Life, widely regarded as its most pleasing scene. Smillie’s handsome engraving of Youth lacks the color of the original canvas, of course, but was otherwise an impressively faithful and detailed reproduction (fig. 3). The delicacy of the atmosphere, delineated in parallel lines with machine ruling in a way only possible with steel engraving, was a particular mark of quality.22 The print was popular and helped to keep the AAU’s membership afloat for another year, but the planned prints of the other three works in the series did not come until later. When the AAU liquidated its properties in 1852, the same Rev. Abbott of the Spingler Institute purchased the Youth engraving plate and promptly hired Smillie to engrave the other three works as well, commissioning a four-engraving set that he sold broadly to benefit his institute (see fig. 2). Although there were other more modest efforts to reproduce The Voyage of Life in print form, these were surely the prints that belonged to Lily’s relations in The House of Mirth and the “steel-engravings” that hung on the walls of Delia’s drawing room in The Old Maid.

Critical reception of the Smillie prints was divided. This was the second time New York critics had seen a retread of the series—the first time being Cole’s own oil copies ten years before—and some saw the theme as dated, the allegory pat and contrived, and the semifantastical landscape forms not true enough to nature.23 The rhyming aphorisms that Spingler chose to include underneath the images probably did not enhance their reception among the intelligentsia.24 But the New York Times praised the way the prints brought the beauty of Cole’s work “within reach of all men of culture and taste,”25 and Wharton’s use of them as part of her mise-en-scènes seems to confirm that they found their way into the homes of mid-nineteenth-century New York society.

When, in The Old Maid, Delia—just five years a bride—gazes contentedly around her well-appointed Gramercy Park drawing room, the prints are relatively fresh acquisitions, perhaps wedding gifts, meant to represent the unimpeachable taste of the old New York family into which she has been fortunate enough to marry (24).26 But as time wears on, Delia’s décor remains drearily unchanged. Although the engravings after Cole are not mentioned again, another print series, Léopold Robert’s The Four Seasons, which Delia had once admired, begins to haunt her. Looking at the colored lithographs on her bedroom walls in a moment of crisis, “she understood that she was looking at the walls of her own grave” (51). Robert’s series is very different from Cole’s, but scholar Tillman Seebass notes that it, too, moves from a youthful and felicitous springtime to a bleak and desolate winter (fig. 4).27 At stake is not only how perceptions of artwork can change with fashion and with age but also how the aesthetic and literary theme of the seasons of life—including its inevitable conclusion, death—interweaves with the plots of Wharton’s novels and her protagonists’ psyches.

Cole similarly fell out of fashion by the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and the oil versions of his once-beloved series also largely disappeared from public view before entering museum collections in the second half of the twentieth century.28 But the twenty thousand AAU engravings of Youth, along with the unnumbered Spingler edition, lived on in drawing-rooms across the United States.29 As Paul Schweizer details in his monograph on the series, Voyage of Life imagery took on a life of its own, appearing on lantern slides and cartes de visite, inspiring religious tracts and political cartoons, and even serving as advertising for patent medicines.30 If, as Wallach suggests, Cole’s ambition was for the series to be popular, then it succeeded perhaps more fully than he intended. It is little wonder that a nineteen-year-old Lily Bart, ten years before the main action of The House of Mirth begins, would have scorned it as the province of “dingy” people.

Cankering Cares

Still, it is a mistake to assess Lily’s opinion about The Voyage of Life, expressed in the form of a memory in the novel’s first pages, as a static one rather than a callous, youthful perception that may or may not still be in place. It is also a mistake, as nearly all commentators have done, to assign Lily’s stated opinion (or Delia’s, for that matter) seamlessly to Wharton herself. It is reasonable to judge that Wharton’s personal aesthetic tastes did not particularly lean to Cole or his ilk—her 1897 book on design, The Decoration of Houses, favors European art and décor—but what is relevant here is not how Wharton herself felt about The Voyage of Life and the engravings after it but what she imagined her protagonists to feel about them. What would they have symbolized to these upper-class women occupying different eras, different situations, and different New Yorks?

To begin with, there is Cole’s and Wharton’s shared theme of the loss of innocence. As each novel begins, the main characters are past childhood and just beginning to lose their belief in the guileless dreams of youth: Lily’s that she might marry “an Italian prince with a castle in the Apennines” (33); Delia’s that all respectable women will be rewarded with an existence as comfortable as her own. In Cole’s Youth canvas—the best known of the four, thanks to the AAU’s print—the voyager reaches ambitiously toward a glowing castle in the sky, not unlike the castle of Lily’s imaginings, unaware of the perilous ravine his boat must navigate as he continues on his path. This is the path that awaits Lily, as she realizes the terrible moral and financial mistake she has made, as well as Delia’s cousin Charlotte, who must break her engagement rather than risk discovery of her child born out of wedlock. As The Old Maid progresses, that child, Tina, in turn navigates the same treacherous moral landscape that lies between youthful desire and worldly success; the central conflicts of both novels’ plots thus align most closely with the stormy skies, threatening rapids, and looming rock forms of Cole’s Manhood. As Cole writes in his texts accompanying the 1840 exhibition of the series:

Trouble is characteristic of the period of Manhood. In Childhood there is no cankering care; in Youth no despairing thought. It is only when experience has taught us the realities of the world, that we lift from our eyes the golded veil of early life; that we feel deep and abiding sorrow.31

Mentally replacing “manhood” with “adulthood,” we can see how the journey of Cole’s voyager parallels those of Charlotte and Lily, even possibly to the point of explaining the error in Lily’s youthful dismissiveness of The Voyage of Life and its moral message.32

Cole’s use of the word “cankering” is interesting, not least because Louis Legrand Noble elected to change this term to “carking” when he reprinted the Voyage of Life exhibition texts otherwise near-verbatim in his 1856 biography of Cole.33 Either of these similar words makes sense contextually, but their meanings are distinct. While “carking” means worrying or troublesome, “cankering” suggests infection or rot; Webster’s defines the verb “canker” as “to corrupt the spirit of.”34 Cole’s purposeful use of the term, despite Noble’s later editing, is confirmed in the former’s 1844 heroic poem inspired by The Voyage of Life: “Children are buds of Heav’n ‘tis earthly air / that breeds the cankers, guilt and deadening despair.”35 In the Manhood canvas, those cankers are visible in a literal way, in the form of three sinister faces hovering in the air above the struggling voyager’s head (fig. 5). These “demon forms” are, Cole explains, “Suicide, Intemperance, and Murder, which are the temptations that beset men in their direst trouble.” This, too, maps to the novels under examination here: Lily, intentionally or not, dies by her own hand, and Charlotte suffers the consequences of sexual intemperance. Delia, meanwhile, effectively murders the mother-daughter relationship between Charlotte and Tina, and indeed, her private thoughts make this metaphor explicit: “She had once learned that one can do almost anything (perhaps even murder) if one does not attempt to explain it. . . . She had never explained the taking over of the foundling baby; nor was she now going to explain its adoption” (64). But she also seems somehow to be herself a victim of murder as she sees her own grave in the prints on her bedroom walls.36 Lily’s, Charlotte’s, Tina’s, and Delia’s perilous paths through adulthood, the risk of corruption to their spirits, and their literal and metaphorical deaths are all set out in the earliest pages of each book with the allusion to The Voyage of Life.

The Republic of the Spirit

A key theme of The House of Mirth is the struggle between worldly success and the preservation of the spirit. In a pivotal conversation Lily has with Lawrence Selden, her problematic love interest, early in the novel, he articulates his idea of a “republic of the spirit” as a metaphorical place that is free of all material cares, and he describes it both as “my idea of success” and as the object of a journey.

He sat up with sudden energy, resting his elbows on his knees and staring out upon the mellow fields. “My idea of success,” he said, “is personal freedom.”

“Freedom? Freedom from worries?”

“From everything—from money, from poverty, from ease and anxiety, from all the material accidents. To keep a kind of republic of the spirit—that’s what I call success.”

She leaned forward with a responsive flash. “I know—I know—it’s strange; but that’s just what I’ve been feeling today.”

He met her eyes with the latent sweetness of his. “Is the feeling so rare with you?” he said.

She blushed a little under his gaze. “You think me horribly sordid, don’t you? But perhaps it’s rather that I never had any choice. There was no one, I mean, to tell me about the republic of the spirit.”

“There never is—it’s a country one has to find the way to one’s self.”

“But I should never have found my way there if you hadn’t told me.”

“Ah, there are sign-posts—but one has to know how to read them.” (61)

The moralizing tone of this Socratic-style exchange and its embedded landscape/ journey metaphor allude to both the ancient philosophers and The Pilgrim’s Progress—but perhaps Selden is not so reliable a narrator as Plato or Bunyan.37 Whenever Lily makes decisions in deference to Selden’s evanescent ideal, she seems to venture further from the remote republic of the spirit, heading down ever more precipitous paths. We have already discussed the tinge of financial risk and loss that attaches to both The Voyage of Life and The House of Mirth; this is present, too, in The Old Maid, where Charlotte’s reduced circumstances keep her and Tina dependent on Delia, who eventually fully subsumes and erases their mother-child relationship. Like Lily and Charlotte, Cole’s voyager never reaches his castle in the sky, which is, after all, only a mirage. Meanwhile, although Delia is successful by any measure a woman of mid-nineteenth-century New York could reasonably expect, she feels that her existence is a living death—and Lily constantly evades various opportunities for social success partly because she fears that her own fate may be a similar one. There is also a whiff of failure about The Voyage of Life, embedded not only in its own narrative but also in its history as a kind of swan song for both the AAU and Cole—so it only follows that both Delia and Lily would look on it with ambivalence in the prelude to their own futures. And yet it is possible that the failure it seems to convey—with peace if not victory at the end—may be preferable to some kinds of success.

Indeed, all of these stories end in death: The Voyage of Life and The House of Mirth literally so, and The Old Maid with Delia’s psychic death and the death of Charlotte’s motherhood—a secret that, as the novella ends, we understand will never be revealed. Death is part of the history of The Voyage of Life itself, as well, with the deaths of both patron and painter preceding the series’ moment of greatest visibility. As Cole’s reputation languished in the latter years of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, the paintings, too, experienced a kind of living death in their many years of obscurity—unlit and uncared for on the walls of two different hospitals, where the cycle of birth, life, and death repeated ceaselessly all around them.38

Death is, of course, the only possible ending for the voyage that is human life, so my intention here is not to demonstrate that either Cole or Wharton was working in a particularly maudlin or retributive mode. Additionally, it would be too much to tie the narratives of any of Wharton’s characters too single-mindedly to The Voyage of Life. To do so would put unreasonable weight on Cole’s series as a symbol when Wharton’s writing, particularly in The House of Mirth, is replete with so many other aesthetic and literary allusions.39 My argument is that the opening references to prints after The Voyage of Life in both The House of Mirth and The Old Maid are no mere throwaway lines; they allude meaningfully to very specific works of art that Wharton’s readers would have known and understood, if only subconsciously, as intersecting with her novels’ themes of innocence lost, ruin, and death. Even as both Lily and Delia begin their stories by conveying ambivalence about The Voyage of Life, it provides a historical, narrative, and moral framework that their paths will follow.

Cite this article: Jessica Skwire Routhier, “The Republic of the Spirit: Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life in Two Novels by Edith Wharton,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18881.

Notes

Many thanks to my colleagues at Panorama, especially Emily Burns and Vanessa Schulman, for encouraging and improving this article. Thanks as well to copy editor Annika Fisher for having my back in this and all things Panorama.

- Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth, ed. Elizabeth Ammons, 2nd Norton Critical Edition (1905; New York: W. W. Norton, 2018). All subsequent quotations from the book are from this edition. ↵

- This is true of Cole/American landscape scholars Paul D. Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life (Utica, NY: Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, 2014), 62; and Dean Flower, “The Hallucination of Landscape,” review of Landscape and Written Expression in Revolutionary America, by Robert Lawson-Peebles, Hudson Review 41, no. 4 (Winter 1989): 745; as well as Wharton scholars Janet Beer, Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth” (London: Routledge, 2007), 23; and Helen Killoran, Edith Wharton: Art and Allusion (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1996), 23 (who misidentifies the series title as The Journey of Life). The Voyage of Life is surprisingly overlooked by scholars working at the intersection of Wharton and the visual arts. Emily Orlando does not mention it at all in Edith Wharton and the Visual Arts (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007). Wendy Steiner addresses it only to exclude it from her larger exploration of ekphrasis in Wharton’s oeuvre: “These four images, of infancy, youth, maturity, and old age, are icons of contingency, narrative in progression and deterministic in presentation of life. The four-part sequence is exactly the opposite of the stopped-action tableau essential to ekphrasis”; in “The Causes of Effect: Edith Wharton and the Economics of Ekphrasis,” Poetics Today 10, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 288. ↵

- Edith Wharton, The Old Maid (1924; Mineola, NY: Dover Thrift, 2019). All subsequent quotations from the book are from this edition. ↵

- Cole signaled his interest in these themes in his list of “Subjects for Pictures,” noting, “The Golden Age—The Age of Iron &c from Hesiod & Ovid.” Cole’s list quoted in Angela Miller, The Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825–1875 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993), 53n72. For more on Cole’s precedents and sources, see Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 64n21. ↵

- On Vasari, see Maia Wellington Gahtan, “Giorgio Vasari and the Image of the Hour,” in “The Inspiration of Astronomical Phenomena VI” (proceedings of a conference held October 18–23, 2009, Venice, Italy), ed. Enrico Maria Corsini, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series 441 (2011): 169–79. Gahtan connects Vasari’s cycle to his explorations of times of the day, including a quadripartite concept of “Dawn, Day, Dusk, and Night” that also maps to the four Voyage of Life compositions (172). ↵

- See Michael Kammen, A Time to Every Purpose: The Four Seasons in American Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 46–71, and for the motif’s evolution into American visual culture, see esp. 74–107. Kammen notes that The Voyage of Life “has a very strong seasonal aspect” (90). My thanks to Arlene Palmer for providing this source. ↵

- The phrase is Wharton’s; just two paragraphs after the younger Lily mentally scoffs at The Voyage of Life, she recalls how “the previous year she had made a dazzling début fringed by a heavy thunder-cloud of bills” (29). Wharton continues, “The light of the début still lingered on the horizon, but the cloud had thickened; and suddenly it broke,” using landscape metaphors that hew closely to the visual progression of the just-mentioned series. ↵

- See Alan Wallach, “The Voyage of Life as Popular Art,” Art Bulletin 59, no. 2 (June 1977): 234–38. Wallach also notes that Cole saw the series as something of an answer to his earlier series The Course of Empire, which he feared was too esoteric for the public. ↵

- Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 38n38. Subsequent details about the history of The Voyage of Life are gleaned from this source as well as from Schweizer’s thorough chronology of the series, published online as Paul D. Schweizer, “The Voyage of Life: A Chronology,” Traditional Fine Arts Organization, accessed September 4, 2023, https://www.tfaoi.org/aa/2aa/2aa612.htm (hereafter Schweizer, “Chronology”). The website notes that the chronology “is reprinted from the 1985 exhibition catalogue titled Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, published by The Museum of Art, Munson-William-Procter Institute, Utica, New York.” ↵

- Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 40–41. ↵

- See Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 41. ↵

- Thomas Cole, “Cole’s Pictures of The Voyage of Life Now Exhibiting at the New Building” (New York: William Osgood, 1840), courtesy New York Public Library. My thanks to Anne Monahan for securing a scan of this for me, through a request to the Consortium of Art and Architectural Historians listserv managed by Princeton University. All subsequent quotes from this source are from that scan. ↵

- Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 49. ↵

- Kimberly Orcutt identifies this address for the Free Gallery in “Power Failure: The American Art-Union Experiment,” in Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons: Collecting American Art in the Long Nineteenth Century, ed. Linda S. Ferber and Margaret R. Laster (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2024), 57. Most subsequent details of the organization’s history appear in Orcutt’s chapter and in Rachel Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City: The Rise and Fall of the American Art-Union,” Journal of American History 81, no. 4 (March 1995): 1534–61; Rachel Klein, Art Wars: The Politics of Taste in Nineteenth-Century New York (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), esp. chaps. 1 and 2; Kimberly Orcutt, “The American Art-Union and the Rise of a National Landscape School,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.1.14; Joy Sperling, “‘Art, Cheap and Good’: The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002), https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring02/196–qart-cheap-and-goodq-the-art-union-in-england-and-the-united-states-184060. See also Orcutt’s forthcoming The American Art-Union: Utopia and Skepticism in the Antebellum Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 2024); Patricia Hills, “The American Art-Union as Patron for Expansionist Ideology in the 1840s,” in Art in Bourgeois Society, 1790–1850, ed. Andrew Hemingway and Will Vaughn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 314–49, esp. 322–24; and Patricia Hills, Peter J. Brownlee, Randy Ramer, and Amanda Lett, Perfectly American: The Art Union and Its Artists (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011). ↵

- Linda S. Ferber, introduction to Tastemakers, Collectors, and Patrons, 6–7; for the estimate of five hundred thousand visitors, see Sperling, “Art, Cheap and Good.” ↵

- According to the US Census for 1840, which gives the city’s population at 312,710. See “1840 United States Census,” Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1840_United_States_census. ↵

- Schweizer notes: “In an issue of The Literary World published on this date, {J. Taylor} Brodt was described as ‘one of a club of five who purchased a single ticket,’ with the pictures subsequently becoming his property alone ‘by lot in an arrangement among the partners’”; in “Chronology,” entry for January 6, 1849. Thus Brodt had invested just one dollar in his successful bid to win a work of art originally commissioned for five thousand dollars; Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 16. For Abbott’s purchase of the work, see Schweizer, “Chronology,” entry for July 5, 1849. ↵

- For these criticisms, and the mechanisms that brought about the demise of the AAU, see Orcutt, “Power Failure”; and Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City.” ↵

- Sperling, “Art, Cheap and Good.” ↵

- See Steiner, “Causes of Effect.” ↵

- See Andrew Raftery, “James Smillie Engraves a Voyage of Life,” Art in Print 7, no. 2 (July–August 2017): 15; and Schweizer, “Chronology,” entry for July 27, 1848. ↵

- Raftery, “James Smillie Engraves a Voyage of Life,” 13. ↵

- {William J. Stillman?}, “Allegory in Art,” Crayon 3 (April 1856), 115. ↵

- On these inscriptions, see Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life, 55. ↵

- “Cole’s Voyage of Life,” New York Times, May 3, 1856, cited in Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 57. ↵

- It is worth noting that Wharton has her timing slightly wrong here. Having previously noted that Delia was married, at age twenty, in 1840, this moment in which she is five years into her marriage must be 1845, well before any engravings of The Voyage of Life were produced. Klein notes that Wharton similarly has Newland Archer and the Countess Olenska of The Age of Innocence (1920) touring the Central Park galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art before the museum occupied that site; see Art Wars, 236. ↵

- Tilman Seebass, “Léopold Robert and Italian Folk Music,” World of Music 30, no. 3 (1988), 78. Seebass’s analysis relates to the original set of easel paintings that was to be Robert’s magnum opus had he not died without completing the autumn scene in 1835. I could find no evidence of colored lithograph reproductions produced in the mid-nineteenth century; illustrated here is a period engraving of the winter scene. ↵

- The Ward set was acquired by the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in 1955, and the Rome set by the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC) in 1971. See Schweizer, “Chronology,” entries for 1908 and June 28, 1908. ↵

- For the number of impressions for the AAU and Spingler prints, see Raftery, “James Smillie Engraves a Voyage of Life,” 15–16. ↵

- Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 58–61. I have argued elsewhere that the moving panorama of The Pilgrim’s Progress that was produced by artists affiliated with the National Academy of Design in 1850–51 is, in part, an homage to Cole and to The Voyage of Life; see Jessica Skwire Routhier, “A More Perfect View Thereof: Landscape, Religion, and the Artistic Underpinnings of the Panorama,” in Jessica Skwire Routhier, Kevin J. Avery, and Thomas Hardiman Jr., The Painters’ Panorama: Narrative, Art, and Faith in the “Moving Panorama of Pilgrim’s Progress” (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2015), 15. ↵

- Cole, “Cole’s Pictures of The Voyage of Life.” ↵

- The journey may also parallel Wharton’s own, given the eventual dissolution of her unhappy marriage, although such biographical analysis is outside the scope of this paper. ↵

- Louis Legrand Noble, The Life and Works of Thomas Cole (New York: Sheldon, Blakeman and Company, 1856), 287–89. ↵

- Merriam-Webster, s.v. “Carking (adj.),” accessed September 4, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/carking; Merriam-Webster, s.v. “Canker (n.),” accessed September 4, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/canker. ↵

- Thomas Cole, “The Voyage of Life” (poem), in Thomas Cole’s Poetry, ed. Marshall B. Tymn (York, PA: Liberty Cap, 1972), 148. ↵

- Robert’s series of The Four Seasons also carries an allusion to suicide, since the artist left the series incomplete when he died by his own hand in 1835. Seebass, “Léopold Robert and Italian Folk Music,” 59. ↵

- Julia A. Galbus connects Selden’s “republic of the spirit” to Plato’s Republic in “Wharton’s Material Republic: ‘The House of Mirth,’” Edith Wharton Review 20, no. 2 (Fall 2004), 3–7. ↵

- The Ward set, after changing hands a few times, hung at St. Luke’s Hospital in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of New York, while the Rome set was at Scarlet Oaks, the former home of its Cincinnati purchaser, which became a sanitorium by 1910 (Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life, 51) and, by the time of this writing, was operating as an assisted living community; https://scarletoakshc.com/virtual-tour. ↵

- See, for example, Killoran, Edith Wharton: Art and Allusion; Orlando, Edith Wharton and the Visual Arts; Steiner, “Causes of Effect”; and Candace Waid, Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991). I explored Wharton’s allusions to classical and Baroque sculpture in “‘The Mask of a Very Definite Purpose’: Sculpture and Masquerade in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth,” paper presented at the College Art Association Conference, February 17, 2023; an article-length treatment is currently in development. ↵

About the Author(s): Jessica Skwire Routhier is the managing editor of Panorama.