Sargent Claude Johnson

PDF: Garnier, review of Sargent Claude Johnson

Curated by: Dennis Carr, Huntington Library; Jacqueline Francis, California College of the Arts; and John P. Bowles, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Exhibition Schedule: Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA, February 17–May 20, 2024

Exhibition Catalogue: Dennis Carr, Jacqueline Francis, and John P. Bowles, eds., Sargent Claude Johnson, exh. cat., with a contribution from Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2024. 132 pp.; 95 illus. Hardcover: $40.00 (ISBN: 978-0300271997)

Five copper masks on a curved wall greeted visitors to the exhibition Sargent Claude Johnson at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens outside of Los Angeles. Johnson (1888–1967) based these sculptures on wooden African masks at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia that were reproduced in critic and theorist Alain Locke’s influential anthology, The New Negro (1925). The smooth surface of the copper masks mimics the high polish of wooden African carvings. This material shift, from wood to metal, signals the artist’s critical response to dominant discourses in modern art. Unlike European painters, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, whose engagement with African masks as objects of a “primitive” past informed their Fauvist and Cubist styles, Johnson insisted that his metallic masks amalgamated modern, dignified faces he encountered daily across northern California, where he lived and worked. Sculptures like Mask (Negro Mother) (1935, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art [SFMoMA]), formed from lustrous metal and accented with paint, celebrate the Black experience of the here and now.

Supported by Locke, Johnson was a key figure of the Black Renaissance: an era of intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic resurgence within African American arts across several US cities, often with a focus on Harlem in New York City.1 Johnson “participated in more exhibitions and received more prizes, awards, and commissions than did Aaron Douglas, Archibald Motley, Jr., or a number of artists who are today better known and more widely exhibited,” as articulated by art historian Gwendolyn DuBois, suggesting a critical misalignment in the field.2 As the first exhibition to focus on Johnson in more than twenty-five years, Sargent Claude Johnson operates as a corrective by reconsidering a critical voice in twentieth-century modernism through a diverse array of media.

Moving from intimate sculpted portraits to monumental figural reliefs, visitors encountered a persona deeply invested in material experimentation across extremes in scale over a single career. Curators Dennis Carr, Jacqueline Francis, and John P. Bowles challenged the spatial expectations of museum display by underscoring the artist’s engagement with the built environment through reconstruction or projection. The exhibition catalogue delves into Johnson’s family history, his approach to modernism, and his artwork both within and beyond the gallery walls. Between the exhibition and catalogue texts, the sculptor’s work is revealed to comprise a spectrum of subjects, styles, and materials key to the multiracial diversity of the Bay Area while also prompting a Pacific-centered vision of American modern art. This approach broadens the geographical scope of African American art scholarship, which often centers cities like New York and Chicago, as well as the Atlantic.

The first gallery demonstrated Johnson’s aesthetic commitment to images of Black humanity and dignity through a range of media and styles: figural chalk drawings, Cubist-inspired lithographs, terracotta portraits of Black women, and copper masks. Two of his most famous sculptures, Forever Free (1933, SFMoMA) and Negro Women (c. 1935, SFMoMA), were positioned at the center of the gallery, tying together smaller works along the gallery’s walls that exhibited a range of approaches to the female figure, including Cubist abstraction. Both sculptures had interpretive texts placed at their fronts and backs to encourage engagement in the round. The front-facing labels focused on Johnson’s commitment to crafting dignified portrayals of Black Americans. The rear label for Forever Free raised questions around representations of Black motherhood, a topic Shaw explores through a detailed examination of Johnson’s childhood in the catalogue. For Negro Woman, the rear text revealed Johnson’s innovative sculptural process: he first created a core out of redwood, which he covered with fine linen and plaster and then modeled and painted. Johnson’s work was introduced as prismatic in terms of the material and style used to represent the human form.

Themes of material experimentation continued in a side gallery titled “Portraits of Children.” This series of five small ceramic busts was influenced by friends that Johnson’s daughter, Pearl, made while living in a multiracial yet segregated neighborhood in Berkeley (fig. 1). Navy blue walls and warm spotlights amplified these jewel-like works that would have been overwhelmed in a larger gallery. Head of a Boy (c. 1928, Huntington Library) and Elizabeth Lee (1927, SFMoMA) showcase Johnson’s adeptness at glazes and the critical influence of the ancient artistic traditions of Egypt, West Asia, and China on the sculptor’s oeuvre. This exploration of materials, techniques, and style positioned Johnson within emerging networks of global modernism beyond Europe and the northeastern United States. A chapter in the catalogue by the curators expands on these discussions of style and inspiration within the show, tracing the artist’s influences from three directions—“looking east to Africa, south to Latin America, and west through the Golden Gate and across the Pacific to Asia”—to propose another direction for the study of American modernism.3

Another successful curatorial intervention was found in a simple, double-sided vitrine of seven small sculptures (fig. 2). One side held materials from across the Americas: redwood, cast stone, terracotta, Oaxaca clay, copper, and enamel. Visitors were encouraged to touch samples, sparking connections to the sculptural display through tombstone information. Such an exercise fortified slow looking within the galleries while activating haptic knowledge essential to the study of sculpture. Viewers were rewarded for their close looking on the opposite side of the vitrine. Extended labels connect the style, materials, and motifs of each sculpture to Johnson’s travels throughout Mexico. This is an excellent strategy to encourage audiences to look again—a call to return to a series of works multiple times from different perspectives.

Departing from the intimate works of the first two galleries, the exhibition shifted in scale to showcase Johnson’s site-specific works for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression. He was one of only three Black supervisors for the Federal Art Project under the WPA nationwide. From conception to physical placement, the exhibition centered Johnson’s project for the California School for the Blind in Berkeley. It was commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project in 1933 as a series of jungle scenes made from carved, painted, and gilded redwood for the school’s auditorium: a proscenium relief above the stage installed opposite an organ screen for the choir loft, connected by carved lunettes. When the school moved to a new building, the commission was broken up across four institutions. The Huntington Library acquired the organ screen from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2011. The trunk of a tree is central to the composition, with two children looking up toward a pair of birds, mouths open in song. Branches radiate out in parallel lines to evoke radio waves. The crisp articulation of outlines and flat profiles of animals suggests the influence of Egyptian and Assyrian low-relief carvings. Johnson mobilized the grain of the redwood to reimagine the natural textures of his subjects, including rabbit fur, bird feathers, and palm fronds. Hints of red paint and gilding animate these low-relief screens. Canvas backs this scene, which allowed sound to permeate the work and fill the auditorium.

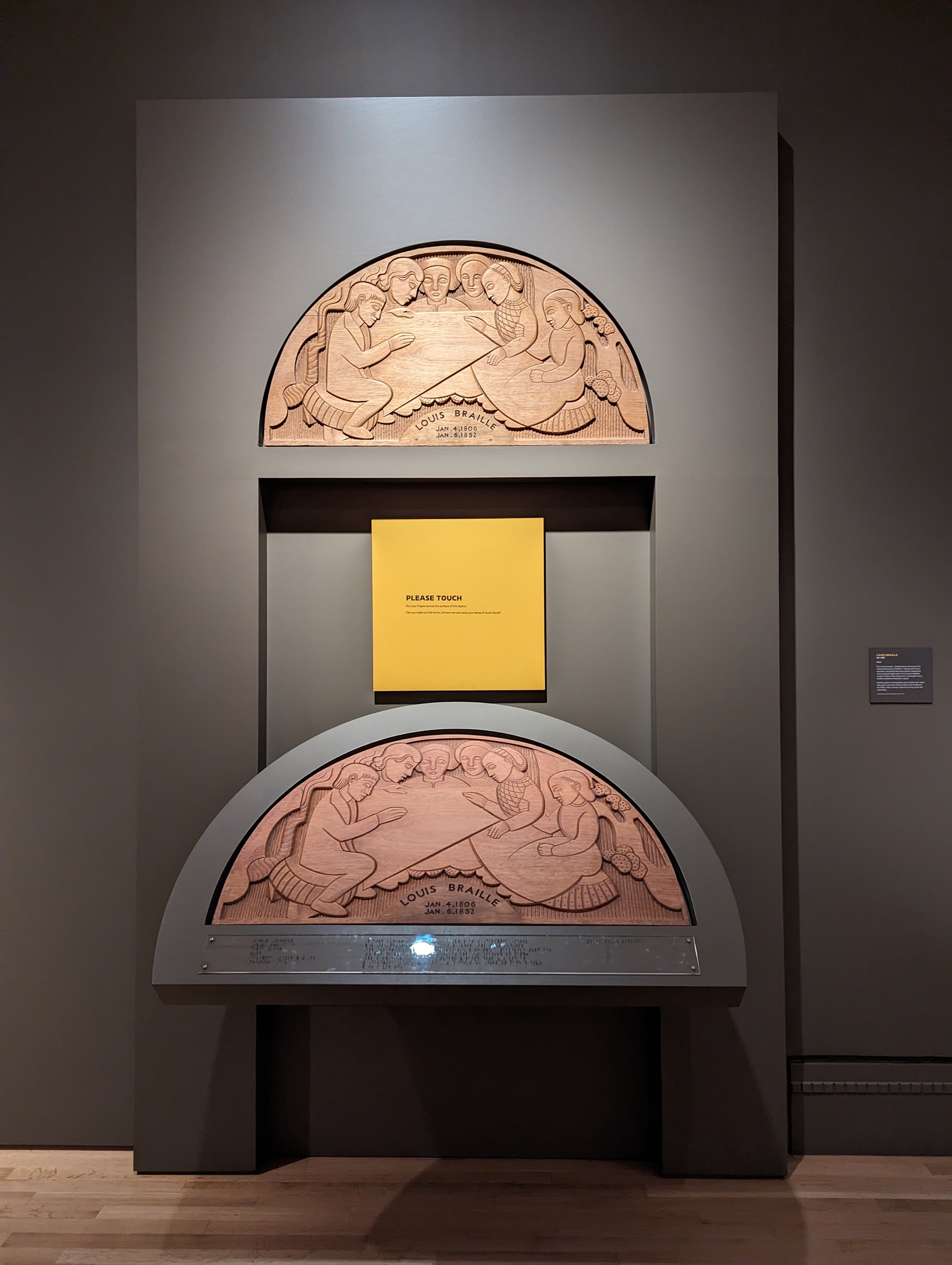

Reuniting this commission for the first time in decades, the curatorial team at the Huntington attempted to reanimate these screens in several ways (fig. 3). As a part of the original installation, Johnson carved a lunette featuring French educator Louis Braille teaching students to read his system of writing with raised dots. Exhibition visitors were invited to touch a replica of the lunette—to feel the relationship between woodgrain, texture, and depth in Johnson’s reliefs—and encouraged to reflect on the role of braille in communication and learning. Braille is included alongside the lunette’s label, and braille books containing all text related to the exhibition were available for tour groups. Wall texts for the other carvings included historical photographs of the proscenium in process at Johnson’s home as well as installation images at the California School for the Blind. An organ composition by the blind British composer Alfred Hollins plays in the background—just as it did within the auditorium in the 1930s. These multisensory embellishments of touch and sound allowed for Johnson’s work to connect to modernist discourses beyond the visual and to fully engage a variety of audiences, both past and present.

The exhibition progressed into the 1940s and focused on another monumental work: Athletics, a 185-foot stone-cast mural installed along the football field of the George Washington High School in San Francisco. Shifting from wood to cast concrete, Johnson’s overlapping figures of men and women competing in various sports allude to the style and grandeur of Egyptian and Assyrian bas-reliefs. Many of Johnson’s surviving works from his later career are site-specific, expanding considerations of material to the built environment. Ironically, dematerialization as projection provided a path forward for curators. Framed by an architectural drawing and cast model, a six-minute video projected onto a gallery wall cycles between a full-scale pan of the frieze and wide-angle views of the site. In the catalogue, Carr and Bowles extend discussions of Johnson’s site-specific murals in their essays on Athletics and Sea Forms (1939), designed for the Aquatic Park Bathhouse and now the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

The exhibition concluded by examining Johnson’s experimentation with industrial enamel in two- and three-dimensional works from the late 1940s until his death in 1967, coinciding with the Civil Rights Movement. Labels drew attention to technical details, including the seemingly automatic scratch drawing of Johnson’s sgraffito work and the science of enamel firing. Additionally, didactic texts returned to major concepts introduced in the first gallery on the Black Renaissance but now explored within the context of the Civil Rights era, including the splintering of racial stereotypes and W. E. B. Du Bois’s notion of double consciousness. An untitled self-portrait (1966, San Francisco African American Historical and Cultural Society) made of enamel on steel closed the show. Based on a photograph from earlier in the artist’s career, the sculpture encapsulated the exhibition’s core themes: multiracial identity, tensions between figuration and abstraction, and material experimentation.

Sargent Claude Johnson was a strictly monographic exhibition, which was both its strength and weakness. By maintaining a tight focus on the work of Johnson, the viewer walked away with a clear picture of an artist who embraced material dynamism and experimentation. Including comparative works by his contemporaries, however, would have strengthened viewers’ understanding of the extent of his innovations, as well as why more attention to and study of the Black Renaissance on the West Coast is needed. Furthermore, his imprint on the art world was not addressed, including an indication of those influenced by his work—most notably Faith Ringgold, whose quilted references are discussed in the catalogue’s introduction.

The monographic nature of the exhibition may have been an intellectual and practical choice. Many works on view were loaned from major art museums in California, university museums in Utah and Arizona, or private collections, attesting to the importance of collections physically located in the American West. Sargent Claude Johnson opened only days before The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (February 25–July 28, 2024). The Met’s show oriented the New Negro movement toward and across the Atlantic Ocean and only included one work—a print—by Johnson. A small but mighty counterweight, Sargent Claude Johnson is a powerful call to include Californian artists in narratives of the Black Renaissance. Johnson’s surprising range of materials and techniques, thoughtfully displayed in this exhibition, call us to look beyond the canon in terms not just of who but of what, how, and where.

Cite this article: Christine Garnier, review of Sargent Claude Johnson, Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19318.

Notes

- Curators chose the term “Black Renaissance” throughout the exhibition and catalogue to signal the broader discussion of ideas central to the Harlem Renaissance. For further definition, see John P. Bowles, Jacqueline Francis, and Dennis Carr, introduction to Sargent Claude Johnson, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 11. While more accessible to the public, this term is not of the period and remains a point of contention across scholarship. See Joshua Cohen, The “Black Art” Renaissance: African Sculpture and Modernism Across Continents (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), 18–21. ↵

- Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw makes this critical observation in The Art of Remembering: Essays on African American Art and History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024), 113, see also 131. ↵

- John P. Bowles, Jacqueline Francis, and Dennis Carr, “Sargent Johnson’s Globalism,” in Sargent Claude Johnson, 50. ↵

About the Author(s): Christine Garnier is assistant professor in history of art and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara.