Sigismund Ivanowski: Illustrating Teddy Roosevelt

PDF: Farmer, Sigismund Ivanowski

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery is taking a fresh look at Theodore Roosevelt’s complicated legacy. Although Roosevelt is always featured in our permanent America’s Presidents exhibition, where I currently serve as the lead curator, he will make an appearance in three of the museum’s temporary 2024 exhibitions. Forces of Nature: Voices of the Environmental Movement, on view until September, explores his place in environmental discourse, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, opening in October, will consider how he is remembered and memorialized. The exhibition 1898: U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions, which closed in February, reflected on his role in building a US empire.1 We borrowed John Singer Sargent’s renowned painting of Roosevelt for the latter, which required lending out the portrait by Adrian Lamb featured in America’s Presidents in exchange. The combined demands of these important shows led our team to dig deep into our holdings for a suitable portrait for America’s Presidents.

Our search yielded a distinctive and mysterious oil painting of Roosevelt by the little-known artist Sigismund de Ivanowski (1874–1944) (fig. 1) that had not previously been on public view at the National Portrait Gallery. In the murky, ominous scene, Roosevelt is dressed in formal attire, calmly walking while surrounded by a cannon, vultures, snakes, and other shadowy monsters, many with piercing red and white eyes. These unusual symbols raised many questions that we wanted to answer for ourselves and our visitors. Examining the painter, the period, and the politics of the time sheds light on the imagery embedded in Ivanowski’s enigmatic portrait, now featured in America’s Presidents. When these aspects of the work are analyzed together, they help illustrate mass media’s role in cultivating caricatures and nontraditional forms of symbolism, which, in this case, shaped presidential portraiture. Furthermore, the relationship between Ivanowski and Roosevelt sheds light on the president’s complicated and contradictory views on immigration and race.

Our curatorial files provided some crucial details about Ivanowski’s painting. For example, previous curators had narrowed down the likely date of the painting to between 1908 and 1910. After an intense study, an official from the Theodore Roosevelt Association suggested that Roosevelt’s outfit dates to his time in the White House, since he “rarely wore formal dress after he left the presidency.”2 Additional research determined that since there is no mention of Ivanowski in any of Roosevelt’s extensive writing or official documents, the likeness was most probably taken from photographs. The Roosevelt Association suggested the painting may have been based on photos of Roosevelt’s visit to the Panama Canal. Another researcher suggested instead that the painting most resembles pictures taken during his inauguration.3 In any case, Ivanowski must have taken some liberties in his depiction, and no exact match has been found thus far.

Little is known about Ivanowski; tracking down more about his career and biography in our records proved vital to understanding possible interpretations of his work. When the National Portrait Gallery first considered acquiring the painting in the early 1970s, the artist was misidentified as Ivan G. Olinsky (1878–1962), a Russian painter also known for his portraits.4 It took several letters before Olinsky’s daughter clarified that her father never mentioned painting Roosevelt.5 There are some other important clues about the portrait’s symbolism hidden in the written correspondence seeking to identify the true artist. For example, appraiser Victor D. Spark helpfully noted that Roosevelt appears “as a ‘Trust Buster.’”6 However, by far the most insightful letter came from Ivanowski’s grandson David S. Perry. His family files confirm that the painter was indeed his grandfather.7 The National Portrait Gallery’s inquiry spurred Perry to dig further into his family history. On November 10, 1977, he wrote to researcher Frances M. Wilson to learn more about his grandfather’s link to Roosevelt. Wilson replied with a report that the correspondents hoped would “become the definitive source at the Gallery.”8

According to Wilson and confirmed by other sources, Sigismund de Ivanowski (sometimes spelled Zygmunt Iwanowski and later without the particle de) was born to a Polish family in 1874 in Odessa, a city that was then part of Russia and is now in Ukraine. At the time of his birth, the land that would become the nation of Poland was divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria-Hungary. As Wilson wrote, “The family was passionately political despite the non-existence of a Polish state and the intense Russification to which all Polish persons under Russian domination were subjected.”9 Despite these challenges, Ivanowski’s talent was apparent from a young age. While a student at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts, he won a coveted gold medal. The recognition caught the attention of Czar Nicholas II. Ivanowski left Russia to study in Paris, then the international heart of the European art world, before arriving in the United States in 1902.10

Just five years later, Ivanowski explained to a New York Times reporter, “It is the energy and strength in America that I find so wonderful. If some of the people who are expending it in all other lines of work would put into art, there would come in America a Renaissance art boiling with energy.” He added, “I cannot paint snippy things; I feel the bigness and the intensity of the American spirit.”11 As the high-profile interview suggests, in just a few short years, he had successfully established himself as an influential illustrator. He worked for several of the largest magazines of the era, including Century, Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s, and Ladies’ Home Journal. He also painted portraits of popular US actors, like Maude Adams, Ethel Barrymore, Billie Burke, and Geraldine Farrar.12 Given his profession, background, and interest in popular culture and politics, Ivanowski almost certainly would have been familiar with the political cartoons of his era. And by far the most popular political cartoons were published in Puck magazine.

Puck was the United States’ first successful humor magazine. Founded by cartoonist Joseph Keppler in 1876 as a German-language magazine, it grew so popular so quickly that an English-language edition followed the next year. It was physically bigger than most magazines of its era, and it was vivid, both in its sharp tone and inclusion of color cartoons, in contrast to the strictly black-and-white illustrations found in other sources.13 As Kristine Somerville writes, “Puck quickly distinguished itself as America’s cleverest, most irreverent magazine, particularly in its approach to presidential politics and political leadership.”14 Its circulation peaked at 125,000 in 1884, and in a display of its influence, in 1909, Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, wrote to the editors to help dispel rumors that they had requested political favors in return for positive coverage.15 Upon Cleveland’s passing, the editors wrote, “Mr. Cleveland had no supporter more loyal than Puck, and it is in grateful remembrance for the work he did and the ideals he stood by that Puck here adds his tribute to the many already paid.”16

It is little surprise, then, that a leading Republican like Theodore Roosevelt was Puck’s most frequent target.17 Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1901, following the assassination of William McKinley by Leon F. Czolgosz. In a savvy political move, Roosevelt promptly announced that he would “continue absolutely unbroken the policy of President McKinley for the peace, the prosperity, and the honor of our beloved country.”18 However, he would soon find his own political voice as he rose to meet new challenges. Domestically, this frequently meant addressing the excesses of the Gilded Age, a period when corporations and politics operated with little oversight. As citizens literally and figuratively learned how the sausage was made—a saying made famous by Upton Sinclair’s shocking 1906 exposé of the meatpacking industry—there were cross-party-line calls for reforms to business, an end to corruption, and protections for workers. Roosevelt joined the Progressive movement and even unsuccessfully ran for a third term on the Progressive Party ticket, a move Puck opposed.19 His administration regulated aggressive business practices, endeavored to negotiate a “square deal” for labor, signed the Food and Drug Act to monitor food safety, and famously took monopolies to court.

Roosevelt’s views on race and ethnicity were complicated, contradictory, and far from what we consider progressive today. In his monograph Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race, Thomas G. Dyer traces Roosevelt’s ideologies back to the nascent racial theories and scientific Darwinism that he encountered during his privileged upbringing and elite education. He demonstrates how Roosevelt’s ardent belief in the ostensible superiority of the “white race” and the interconnected idea of the “survival of the fittest” helped fuel his imperialist ambitions.20 This was evident in Roosevelt’s own book about his wartime experience in Cuba, The Rough Riders: An Autobiography. To bide the time on his train ride from Texas to Tampa, he read Edward Demolins’s treatise bluntly translated from French as The Superiority of the Anglo-Saxons: To What It Is Due.21 These same nationalistic philosophies caused Roosevelt to worry that “old-stock Americans” faced extinction if they did not increase the rate at which they had children.22 Despite these concerns, Roosevelt knew that immigrants were key to a thriving US society. Historian Edmund Morris observes that Roosevelt supported immigrants who embraced his sense of US ideals if they did not take away resources from natural citizens. As Morris succinctly states, “[He] welcomed the clash of alien cultures so long as it did not result in a mass collision.”23

Roosevelt was also uniquely sympathetic to Poland and Polish nationalism. This was, perhaps unintentionally, evident shortly after McKinley’s assassination at the hands of a Polish American. Rather than focus solely on Czolgosz’s ethnicity, Roosevelt and the press zeroed in on his ties to anarchy, somewhat shielding Polish Americans from retaliation and attacks. As Roosevelt explained in his first annual message to Congress, “President McKinley was killed by an utterly depraved criminal belonging to that body of criminals who object to all governments.”24 More deliberate, in March 1902, Roosevelt hosted Polish patriot, pianist, and future prime minister Ignacy Jan Paderewski for a performance at the White House.25 Paderewski later wrote in his memoirs, “Certain opinions about my country expressed by President Roosevelt were extremely encouraging to me. . . . He was a knight. I had great admiration for him.”26

That fall, while recovering from a leg injury, the president asked Herbert Putnam, the Librarian of Congress, to provide him a book on the history of Poland.27 A few days later, he complained that the work he received was “too short” and expressed a desire to learn more from the “Polish standpoint.”28 According to scholar and diplomat Boguslaw W. Winid, at least some Polish readers were similarly interested in Roosevelt’s biography and historical writings. Several of Roosevelt’s books were translated into Polish, including The Ranch Life and Hunting Trail, in which the publisher notes that after experiencing the US frontier firsthand, “[Roosevelt] then becomes a fierce spokesman against the organization of trusts, and always defends the just and toilsome work of farmers and pioneers as opposed to the unworthy work of capitalists.”29 This mutual respect culminated with Roosevelt suggesting in 1914 that the “Polish Nation in America,” should “organize strongly.” Further, he explained, “I believed in the independence of Ireland, which is [now] an accomplished fact, in the same way I believe in the independence of Poland.”30

Ivanowski followed Paderewski’s musical career, and it is possible that he was aware of his countryman’s view of Roosevelt. In addition, Ivanowski represented exactly the type of immigrant Roosevelt hoped to attract. He was financially successful and, as was clear in his interview with the New York Times, admired US “energy” and potential. The Roosevelt in the foreground of Ivanowski’s painting appears determined and calm in the face of imminent danger, much like the image of a “knight” Paderewski evoked. This depiction of Roosevelt as heroic and stoic was typical of portraits created for a US audience during Roosevelt’s lifetime and shortly thereafter. In the public eye for much of his life, Roosevelt was highly adept at shaping his image. He helped design the “Rough Rider” uniforms he wore in Cuba, which feature prominently in several notable works, including the drawing by Charles Dana Gibson that accompanied his wartime memoirs.31 Like Ivanowski, sculptor Frederick MacMonnies portrayed Roosevelt in movement, even though the president would complain that when it came to jumping horses, his Rough Rider uniform was too stiff for the job.32 In 1903, a frustrated Sargent famously immortalized Roosevelt leaning on a staircase impatiently waiting to get back to work as the painter tested his patience for sittings.33 Though Sargent’s work would become his favorite, Roosevelt also appreciated the portrait by Philip de László, likely because he found the artistic process much more entertaining. László’s wife played the violin, and the president was able to chat with his guests while he was modeling.34 Still steely-eyed, Roosevelt appears more relaxed rendered in László’s brushstrokes than in other depictions.35 However, the now-infamous Theodore Roosevelt Equestrian Statue, created in 1939 by James Earle Fraser, illustrates the modern challenges with these early hagiographic “white knight” portraits. Soaring above the stereotypical figures of Indigenous and Black men flanking it on either side, the sculpture of Roosevelt was removed from its prominent position at the entrance of the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 2022, following years of protest that it was racially insensitive and celebrated Roosevelt’s antiquated colonial ideas.36

While Ivanowski’s depiction of Roosevelt is familiar, the surrounding symbolism sets it apart from other works of presidential portraiture from the period. The art movement called Symbolism, which art historian Hans H. Hofstätter defines as “a moral attitude manifested in literature and visual arts which had recourse to motifs and depictions that were unreal,” emerged in France, Germany, and other parts of Europe in the late nineteenth century. At the turn of the twentieth century, it was not yet widespread in America.37 Ivanowski, who trained in Paris, may have been influenced by the ways his European colleagues combined real and imagined elements to elicit emotion from viewers.38 However, unlike many Symbolist painters, Ivanowski does not appear to have drawn inspiration from religion or mythology.

For some time, I tried to connect Ivanowski’s images to fairy tales or proverbs. After all, he had illustrated works of fantasy, including The Land of the Blue Flower by Frances Hodgson Burnett.39 It was, however, the art appraiser Spark’s suggestion that Ivanowski depicted Roosevelt as a “trust buster” that prompted me to search images that linked snakes with monopolies. After this nudge, I found that it was a common trope across various artistic media to represent John D. Rockefeller Sr. and the Standard Oil Company as serpents. Americans living during the Roosevelt administration would have recognized and understood this symbolism, though today it requires a bit of explanation.

Depending on your perspective, Rockefeller was either a titan of industry whose Standard Oil Company was the most profitable venture in US history or a corrupt robber baron who consolidated power and snuffed out competition with little regard for the law or workers’ rights.40 The measures of Standard Oil’s success are still staggering today. Founded in 1870, Standard Oil controlled 90 percent of US oil refineries by the early 1900s. At the peak of his wealth in 1912, Rockefeller was worth nearly $900 million.41 By some estimates, this would amount to over $28 billion today. With his vast wealth and unconstrained tactics, Rockefeller was a frequent target of Progressive-Era reformers, journalists, and satirists. For those who viewed him as a conniving capitalist with immense financial resources and political influence, the snake was a fitting caricature.

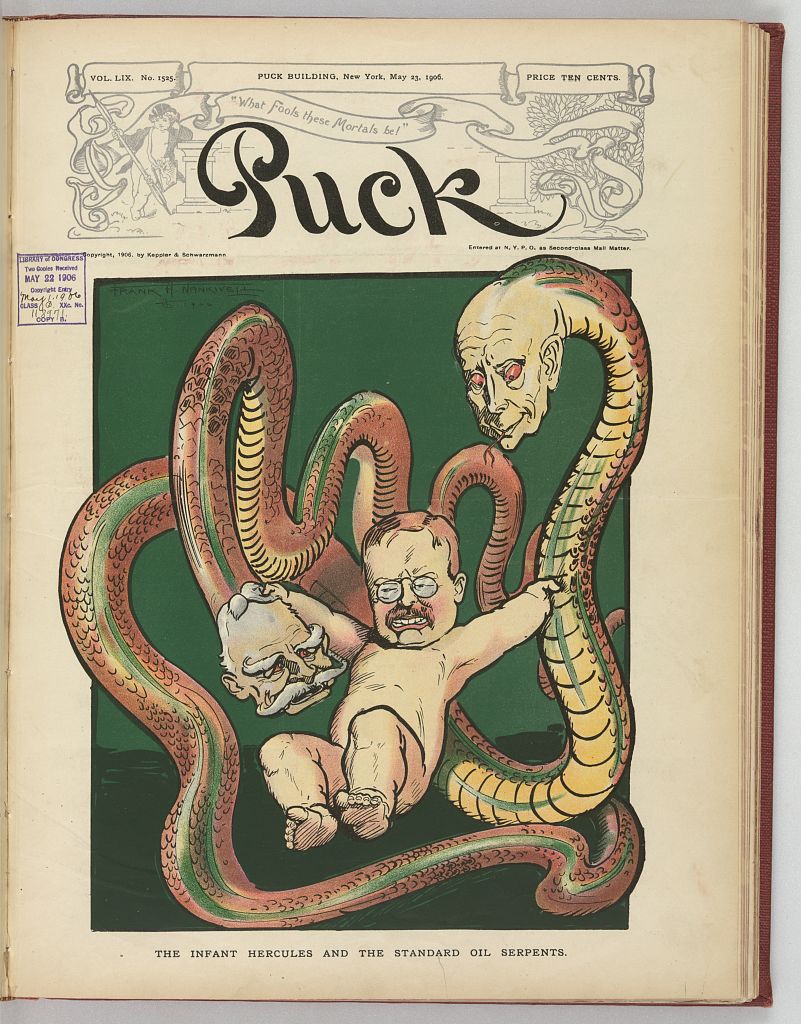

One of the most famous examples of Rockefeller parodied as a serpent adorned the May 23, 1906, cover of Puck. Titled The Infant Hercules and the Standard Oil Serpents by Frank A. Nankivell (fig. 2), it shows Roosevelt as a baby battling snakes representing Rockefeller and political powerbroker Republican Senator Nelson W. Aldrich. This is a direct reference to the Roman myth of the baby Hercules defeating two serpents sent by Juno to kill him as he slept, which implies that even when Roosevelt appeared weak, he was stronger and braver than wealthy businesspeople and established politicians.42

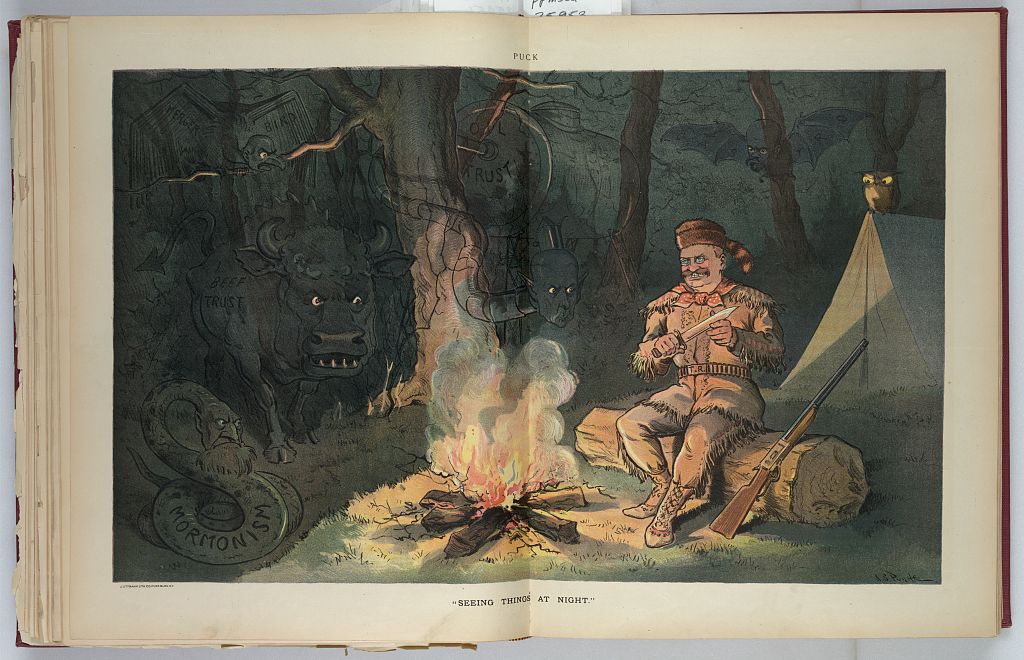

With this revelation, I started to look further into drawings featured in Puck. I found other links, both in style and content, to Ivanowski’s portrait. For example, the gloomy, foreboding tone and composition resemble the May 3, 1905, illustration Seeing Things at Night by John S. Pughe (fig. 3). This cartoon plays on Roosevelt’s often professed and frequently pictured love of hunting. Dressed in buckskin and a raccoon hat, he sits on a log, casually sharpening his knife, bathed in firelight, and unbothered by the monsters that lurk in the forest nearby. Once again, Rockefeller appears as a snake. The other monsters are labeled and include a beef trust bull, a merger bird, an oil trust train, the Castro bat, and another snake representing Mormonism.

These issues reflect the nature of political cartoons—they document the political winds of a particular moment and can be challenging to understand in historical hindsight.43 They also reflect the prejudices of their time, and Puck clearly catered to a white, politically socially progressive male audience.44 While the references to mergers and trusts illustrate Roosevelt’s very public battle to end monopolies of all kinds, Castro and the references to Mormonism represent less well-known political challenges. “Castro” addresses Roosevelt’s dispute with President Cipriano Castro of Venezuela. This conflict would, in part, inspire Roosevelt to issue the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which asserted that the United States, not European powers, had the right and responsibility to intervene in Latin America.45 The snake labeled as “Mormonism” symbolizes the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints’s growing influence on culture and politics and the short-lived fear at the time of the changes that might follow.46

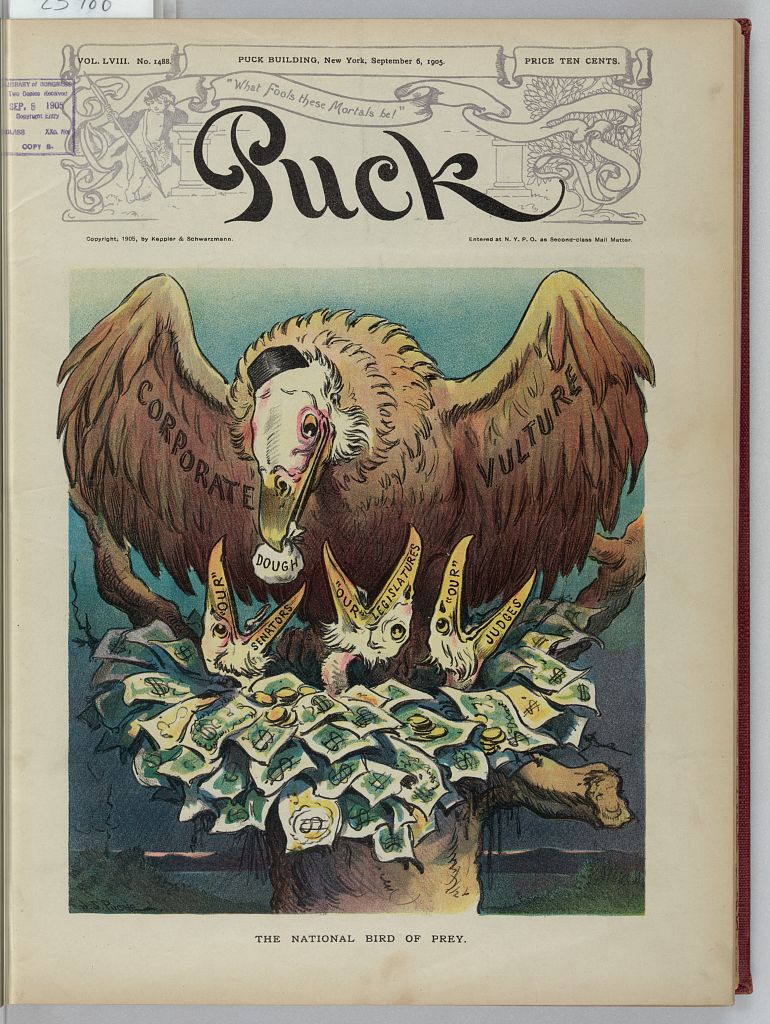

Another cartoon proved equally illuminating in understanding both Ivanowski and Roosevelt. In The National Bird of Prey, also by Pughe, a “corporate” vulture is standing in its nest of money, feeding a bag of dough to baby birds labeled “our senators,” “our legislatures,” and “our judges” (fig. 4). Although it is from August 6, 1905, it addresses a topic still relevant today—the power of extreme wealth to shape the US political system, especially at the national level. It is interesting that Roosevelt and the presidency are not part of Pughe’s criticism. Ivanowski, too, thought that Roosevelt was above the corporate vultures and the undue influence of money. In his painting, there is a sinister-looking vulture with a glaring red eye lurking in the shadows directly above Roosevelt. Even less clear is a similar vulture-like creature that stands nearby facing the viewer, with the outline of its long beak just visible in the dark. Its profile is nearly identical to the bird of prey in the Puck cartoon. Neither corporate vulture catches the president’s attention or causes him to break his stride.

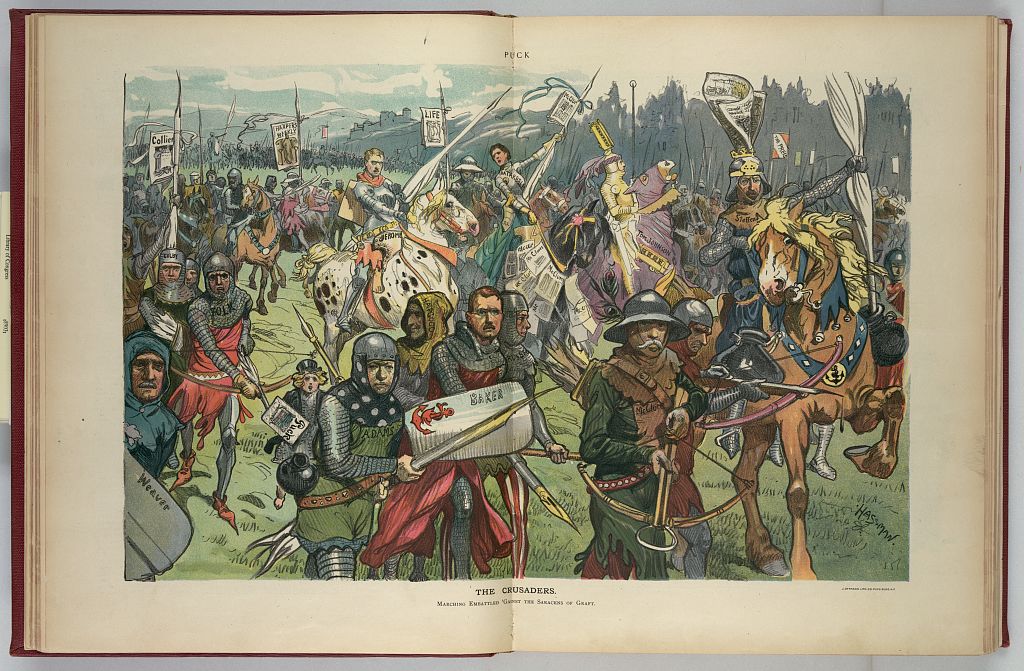

Given the power of Puck and similar publications, it is little wonder Ivanowski includes a fountain pen in the upper right corner. The Progressive Era corresponds with the “golden age” of print media. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s pivotal work The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism provides an illuminating look at the role reporters played in presidential politics. She writes, “Collectively, this generation of gifted writers ushered in a new mode of investigative reporting that provided the necessary conditions to make a genuine bully pulpit of the American presidency.”47 The proverbial pen was at the height of its power, as evidenced by the provoking Puck print The Crusaders by Carl Hassmann (fig. 5).48 This illustration depicts journalists and media sources as knights battling against enemies of “graft,” wielding their pens in place of traditional weapons. The named warriors include Ida Tarbell, who famously exposed Standard Oil; Upton Sinclair; Puck itself; and several of Ivanowski’s employers, including Harper’s Weekly and Life. As an illustrator, Ivanowski may have considered himself among these soldiers battling capitalistic corruption and greed. Indeed, the cannon he included in the middle ground of Roosevelt’s portrait likely had many meanings. It could reference literal fighting, including Roosevelt’s well-known service in the Spanish-American War or his effective arbitration in the Russo-Japanese War, for which he was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. It might refer to his efforts to strengthen the US Navy, which culminated in 1907 with the international tour of the Great White Fleet.49 It could also denote his figurative war against unregulated capitalism. Taken in concert with the pen, it could even symbolize the power of the press.

With these possible references to popular political cartoons, Ivanowski may have been challenging the traditional separation between fine art and popular culture. Yet there is an added layer of interpretation and complexity to this painting that is absent from his commissioned portrait paintings of actors for magazines. The shadowy figures emphasize the incongruent juxtaposition of a calm president with monsters and shadows. The surrounding figures are alive and menacing, perhaps representing the myriad threats to the United States and to the democratic ideals that both Roosevelt and Ivanowski valued. Though these monsters are intended to be frightening, Roosevelt appears unafraid. The symbolism, however, was not obscure, and popular humor magazines provide clues to the meanings behind the snakes, vultures, and pens. At the time, Puck and other chromolithographic cartoon weeklies were highly accessible and relatively inexpensive sources of political discourse and iconography.50 Ivanowski’s portrait is both rich and simple, clever and clear, at the same time.

Both Roosevelt and Ivanowski would go on to fight other foes after the completion of this portrait. Roosevelt lost his 1912 third-party presidential run. In splitting the Republican vote between himself and his successor, William Howard Taft, Roosevelt helped Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson easily win the election. As Wilson navigated the United States’ role in the First World War, Ivanowski joined Paderewski in fighting for Poland’s independence. In 1917, Ivanowski enlisted in the Blue Army, a battalion of volunteers, including many Polish Americans, who fought in France.51 He reached the rank of major while serving as Paderewski’s military attaché. In 1919, Paderewski signed the Treaty of Versailles during his brief stint as Polish prime minister.52 Given their closeness and shared national goals, it is unsurprising that Ivanowski would paint Paderewski’s portrait. “It is difficult to give any unified impression of him with words of pigment,” Ivanowski wrote of his friend and compatriot, continuing, “His confidence is absolute. . . . I was his intimate associate for five years. I never saw that confidence misplaced.”53 There are certainly similarities between the resolute expression and strength apparent in Ivanowski’s two portraits of vastly different world leaders.

Ivanowski eventually returned to the United States and to painting professionally. He settled in Westfield, New Jersey, where he opened a small studio. In 1944, he passed away in New Hampshire under his daughter’s care.54 Roosevelt had died many years earlier, on January 6, 1919, at the relatively early age of sixty. Ivanowski and Roosevelt likely never met, but they come together as artist and subject at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. As historians and curators continually reassess Roosevelt and his presidency, Ivanowski’s work reminds us of the president’s evolving legacy and complex history. Further, the artist’s lived experience and the monster-filled background he created forces us, as curators, to examine sides of the Roosevelt administration that might have otherwise not been part of our interpretation. While our mindfully short label text explains that “the snakes represent the Standard Oil monopoly,” we leave other elements of the canvas unexplained. Perhaps in the future we can pair Ivanowski’s piece with a more traditional presidential portrait to inspire even more historical inquisitiveness. Meanwhile, our work to better understand the enigmatic background in this portrait of Roosevelt underscores the value of looking across media to open new interpretive possibilities. In the case of this presidential portrait, caricatures and the artist’s own cultural experience proved key to understanding the complexity of this rich portrait.

Cite this article: Mindy Farmer, “Sigismund Ivanowski: Illustrating Teddy Roosevelt,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18941.

Notes

- As the exhibition’s curators previously shared in Panorama, “Our goal is to examine the debates around US imperialism, alongside the experiences of peoples living in the Caribbean and the Pacific and the realities of their loss of self-determination”; see Taína Caragol and Kate Clarke Lemay, “Imperial Visions and Revisions,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020): https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10096; and the catalogue, Taína Caragol and Kate Clarke Lemay, 1898: Visual Culture and U.S. Imperialism in the Caribbean and the Pacific (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023). ↵

- Ellen Miles to Marvin Sadik, memo, July 24, 1972, Ivanowski Curatorial File (hereafter Ivanowski File), National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. ↵

- Frances M. Wilson, “Sigismund de Ivanowski, 1874–1944,” Perspectives: A Polish American Educational and Cultural Bi-Monthly 10, no. 2 (September–October 1979): 516. ↵

- “Ivan Olinsky, 84, Portraitist, Dies: National Academy Member Taught Here till December,” New York Times, February 12, 1962. ↵

- Mrs. Leonore O. Miller to Ellen G. Milles, April 1, 1972, Ivanowski File. ↵

- Victor D. Spark to L. LeMoyne Billings, New York City, April 20, 1972, Ivanowski File. ↵

- David S. Perry to Robert G. Stewart, Philadelphia, January 3, 1976, Ivanowski File. ↵

- Frances M. Wilson to David A. Perry, January 12, 1978, box 5, Zygmunt Iwanowski papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford, CA. ↵

- Wilson to Perry, January 12, 1978. ↵

- See the 1930 census record at Enumeration District 0102, FHL microfilm 2341123, p. 8B, Census Place: Mountainside, Union, NJ. ↵

- Otis Notman, “Men Who Make Pictures for Books,” New York Times, February 9, 1907. ↵

- See, for example, “S. Ivanowski, Polish Portrait Painter, Dies: Russian Court Artist,” New York Herald Tribune, April 13, 1944. ↵

- See Stephen Hess and Milton Kaplan, The Ungentlemanly Art: A History of American Political Cartoons (New York: Macmillan, 1975), 104–5. ↵

- Kristine Somerville, “Visual Burlesque: Ralph Barton and Puck Magazine,” Missouri Review 42, no. 2 (Summer 2019): 93–106. ↵

- For the circulation statistic, see Somerville, “Visual Burlesque.” For a discussion of Cleveland, see Hess and Kaplan, The Ungentlemanly Art, 46–47. Cleveland’s letter to Puck quoted in W. A. Croffect, “Puck and the President: Interesting Correspondence between Mr. Cleveland and Joseph Keppler,” Daily American, January 3, 1909. ↵

- “‘What Fools These Mortals Be!’” Puck 63, no. 1635 (July 1, 1908): 2. ↵

- Michael Alexander Kahn and Richard Samuel West, What Fools These Mortals Be: The Story of Puck (San Diego: Library of American Comics, 2014), 43. ↵

- See Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 14–15. ↵

- For discussion of Roosevelt’s progressivism and his Progressive Party candidacy, see Aida D. Donald, Lion in the White House: A Life of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Basic, 2007), 251–57. For discussion of Puck’s position on Roosevelt’s third-party run, see Kahn and West, What Fools These Mortals Be, 43. ↵

- Thomas G. Dyer, Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980). ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt, The Rough Riders (New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1899), 47–48. ↵

- Roosevelt, Rough Riders, 143–45. ↵

- Morris, Theodore Rex, 37. ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt, “First Annual Message,” December 3, 1901, The American Presidency Project, accessed January 27, 2023, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/206187. ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt to Jacob H. Schiff, March 27, 1902, Theodore Roosevelt Papers, Library of Congress Manuscript Division (hereafter Roosevelt Papers), Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library, Dickinson State University (hereafter Roosevelt Digital Library), https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o181852. ↵

- Ignace Jan Paderewski and Mary Lawton, The Paderewski Memoirs (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1938), 368. ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt to Herbert Putnam, October 6, 1902, Roosevelt Papers, Roosevelt Digital Library, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o183200. ↵

- Theodore Roosevelt to Herbert Putnam, October 8, 1902, Roosevelt Papers, Roosevelt Digital Library, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o183200. ↵

- Boguslaw W. Winid, “Theodore Roosevelt in Polish Historiography,” Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal 18 (Fall/Winter 1992): 7. ↵

- Quoted in M. B. Biskupski, “‘I Believe in the Independence of Poland’: Theodore Roosevelt’s Prediction of Polish Independence, 1914,” Polish American Studies 45, no. 1 (1988): 84. ↵

- 1898: U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions, curated by Taína Caragol, Kate Clarke Lemay, and Carolina Maestro, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, April 28, 2022–February 25, 2024. ↵

- James G. Barber, Theodore Roosevelt: Icon of the American Century (Washington, DC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 40. This statue is currently in the collection of the Sagamore Hill National Historic Site at Oyster Bay, NY. ↵

- Barber, Theodore Roosevelt, 49–50. ↵

- Owen Rutter, Portrait of a Painter: The Authorized Life of Philip de László (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1939), 252. ↵

- Barber, Theodore Roosevelt, 7. ↵

- See, for example, Laura Zornosa, “Unanimous Vote Is Final Step Toward Removing Roosevelt Statue,” New York Times, June, 22, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/22/arts/design/theodore-roosevelt-statue-museum-natural-history-removal.html. ↵

- Hans H. Hofstätter, “Faith and Damnation: Religious Depictions in Symbolism,” in Kingdom of the Soul: Symbolist Art in Germany, 1870–1920, ed. Ingrid Erhardt and Simon Reynolds (Munich: Prestel, 2000), 131. ↵

- For another description of symbolism, see Nicole Myers, “Symbolism,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2007, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/symb/hd_symb.htm. ↵

- Frances Hodgson Burnett, The Land of the Blue Flower (New York: Moffat, Yard, 1909). ↵

- For an excellent biography of Rockefeller, see Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (New York: Vintage, 1998). ↵

- Kat Eschner, “John D. Rockefeller Was the Richest Person to Ever Live. Period,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 10, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/john-d-rockefeller-richest-person-ever-live-period-180961705. ↵

- For another visual interpretation of this ancient myth, see Léonard Limosin, Medallion with Hercules Strangling Serpents, 1570, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/27645/medallion-with-hercules-strangling-serpents. ↵

- For a discussion of this cartoon, see “Seeing Things at Night,” Roosevelt Papers, Roosevelt Digital Library, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o278099. ↵

- J. David Valaik includes a discussion of Puck’s audience in Theodore Roosevelt: An American Hero in Caricature (Buffalo, NY: Canisius College Press, 1993), 7–9. ↵

- See, for example, Serge Richard, “The Roosevelt Corollary,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2006): 17–26. ↵

- Around the time of this cartoon, Roosevelt was defending Senator Reed Smoot, an apostle in the LDS church, from various criticisms. For more on this matter, see M. R. Merrill, “Theodore Roosevelt and Reed Smoot,” Western Political Quarterly 4, no. 3 (1951): 440–53, https://doi.org/10.2307/442849. ↵

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013), xii–xiii. ↵

- Carl Hassmann, The Crusaders, February 21, 1906, Roosevelt Papers, Roosevelt Digital Library, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o278490. ↵

- For a solid discussion of the many intentions behind the tour of the Great White Fleet, see Morris, Theodore Rex, 493–96. ↵

- Richard West, “An Explosion of Color: The Age of the Chromolithographic Weekly,” Cartoon America: Comic Art in the Library of Congress, ed. Harry Katz (New York: Abrams, 2006), 120. ↵

- See “S. Ivanowski, Polish Portrait Painter, Dies,” and “Papers of Painter Zygmunt Iwanowski, Friend of Paderewski, Acquired by Hoover Archives,” Stanford University, Hoover Institution, October 14, 2015, https://www.hoover.org/news/papers-painter-zygmunt-iwanowski-friend-paderewski-acquired-hoover-archives. ↵

- For Paderewski’s speech on the treaty, see Bronislas A. Jezierski, “Paderewski and the Treaty of Versailles,” Polish American Studies 11, nos. 1–2 (1954): 42–48. For an assessment of Paderewski’s short role as prime minister, see M. B. Biskupski, “Paderewski, Polish Politics, and the Battle of Warsaw, 1920,” Slavic Review 46, nos. 3–4 (1987): 503–12, https://doi.org/10.2307/2498100. ↵

- Sigismund Ivanowski, “Paderewski the Lion-Hearted,” Ladies’ Home Journal 11 (November 1924), 106. ↵

- See Frances M. Wilson to David A. Perry, Ivanowski File. ↵

About the Author(s): Mindy Farmer is a historian at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.