Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery

Curated by: Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Stephanie Cannizzo, and Ryan Serpa

Exhibition schedule: UC-Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA); July 27–October 23, 2016

The University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) presented Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery, from July 27 to October 23, 2016. The exhibition included eighty-four works, including a number of nineteenth-century cartes de visite that depict Sojourner Truth, a former slave and noted abolitionist whose portraits served as the conceptual premise of the exhibition; these images were complemented by other photographs, negatives, tintypes, dollar bills, and tax stamps addressing aspects of abolition, early American capitalism, and African American portraiture.

The recent gift of cartes de visite to BAMPFA by Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Distinguished Professor in the Arts and Humanities at University of California, Berkeley served as the foundation of the exhibition. Cartes de visite are two-and-one-half by four inch calling cards that include albumen photographs and sometimes text, signature, or stamp. They were cheaply produced, bought, traded, given, and mailed; they were extensively shared and highly accessible. Perhaps what was most important for the thesis of the exhibition was that the cartes de visite “could aggrandize the formerly enslaved,” as stated in the exhibition brochure. Curators did this by showing the breadth and diversity of cartes de visite production and establishing photography, in general, and black portraiture, specifically, as a critical tool of abolition and in the case of Sojourner Truth, as an example of self-actualization.

Sojourner Truth was born a slave, who “could neither read nor write,” yet she wrote an autobiography that was self-published multiple times. An effective orator, abolitionist, proto-feminist, she campaigned for “the right of emancipated slaves to education and property [ . . .] and the elimination of capital punishment,” as asserted in the exhibition brochure. Truth is known for her speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” and for the caption on her cartes de visite, “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” The phrase was both poetic and calculating; Truth asserts herself as author and owner (immeasurably pregnant with meaning at the time) while also describing the utility and metaphoric function of her shadowy photographic image.

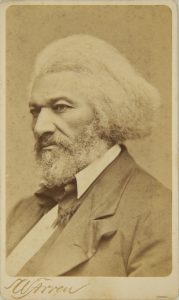

Many of the cartes de visite in the exhibitions were portraits, and several pictured Truth, and while she was an abolitionist, they functioned as a tool for forms of propaganda, communication, and jest. The exhibition also included the work of satirist Thomas Nast and portraits of notable political figures, including President Abraham Lincoln in hand-tinted blackface and Confederate President Jefferson Davis in femme-drag. One carte de visite reproduced a popular portrait of well-known fellow abolitionist Frederick Douglass. In the three-quarter pose, Douglass appeared still and clear-eyed with his signature white coiffure. Also in the exhibition were cartes de visite of Wilson Chinn and other former slaves that were circulated by abolitionists to illustrate the conditions of slavery in the American South.

The location of the exhibition within the building made the exhibition literally difficult to find. While it was of course included on the institutional map, it occupied a transitory space, the Community Gallery, which was not clearly identified, and was between the hands-on Fisher Family Art Lab, elevators, and a research space. Whether intentional or not, the walkway-cum-gallery served the thesis of the exhibition with its necessarily plain and as a result clear display strategy.

Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery was understated and restrained in its presentation. Much of the over eighty objects hung on the east facing wall of what can be described as a thoroughfare. At each end were interpretive exhibition brochures that were also available online at the exhibition website. On the north side was the exhibition title and description, the only wall text; on the south-side was a copy of Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadow and Substance, published in 2015, the book by exhibition curator Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby from which the exhibition brochure content was adapted.

Most works were displayed as two-dimensional objects in-line or grouped along the wall. This presentation felt at once like and unlike a book laid open. The cartes de visite were set on blank, white mats, sparingly framed, in a way that evoked the pages of an album. Others were in small vitrines mounted perpendicular to the wall, giving the cartes de visite a tactile sense of their being objects, something not just to be looked at, but held and in the case of much of the exhibition content, purchased and traded. These differing presentation strategies complemented rather than competed, reminding viewers that cartes de visite circulated in albums, through the mail, and in hand.

Across from this, butted against a glass pony wall and railing, were table vitrines. In one was the exploration of African American portraiture by the curators, Truth’s autobiography with a leather cover embossed with her likeness, along with her collection of autographs.

With almost no wall text, the exhibition brochure served as a critical tool in deciphering the coded context of cartes de visite. Through this text, the exhibition was divided under nine core themes: Civil War; Sojourner Truth’s Uncaptioned Cartes de visite; Sojourner Truth’s Captioned and Copyrighted Cartes de visite; Civil War Debates about Money; Photography as Shadow, Photography as Chemistry; Cartes de visite as Political Weapon; Cartes de visite as Union and Abolitionist Fundraisers; African American Portraiture; Autographs, Paper, and Civil War. One can assume the average guest was not a historian; while many visitors may be more than familiar with the broader strokes of abolition, Civil War history, and even the biography of Truth, her exercise of authorship, her radical self-realization, and the complex relationship between her cartes de visite and commerce were convincingly highlighted and connected throughout the text. These ideas were also immeasurably important to the viewer experience. Guests might move down the walkway, look at a carte de visite, step away to read about the object in the brochure, then return to the image. What could have been heavy-handed detraction from one of the primary functions of the exhibition—looking—instead illuminated much of the social context around Truth’s substance.

The brochure imitates the fading cartes de visite with its minimal color and soft blue type. Three objects, two of Truth’s cartes de visite and a black-and-white photograph, Knowledge Is Power (c. 1870s; black-and-white photograph, Courtesy of Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby), bookend the exhibition and brochure both ideologically and physically. Depending on one’s path, Knowledge Is Power was either one of the first or the last works encountered. In the photograph are rows of nattily dressed black children and young adults. They stand and sit in front of a building, its two widows, and a chalkboard. A woman holds chalk to board under cursive script, “Knowledge is power. Miss E. E. Elliott, Teacher.” It is one of the few large group images included in the exhibition. It is not symmetrical; the black-coated boys make an “L” through their crisp, bright shirted peers. They look directly into the camera. Some faces are stern, some somber, some with closed-mouth smiles. Taken just five years after the Civil War, the brochure describes this image as illustrating a shift from education as a source of ideological wealth to more concrete power. It also embodies Truth’s project for progress for black people and women.

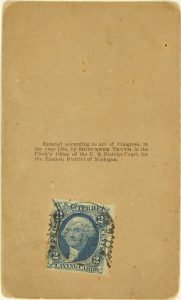

The curatorial narrative was incredibly bold. Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery moved beyond the honorific and the exhibition instead made transparent connections between Truth’s choices, visibility, bondage, and freedom. Of Truth, the curators stated in the exhibition brochure that she “invented her own kind of paper money and for the same reasons as the government: in order to produce wealth dependent on a consensus that representation produces material results, to make money where there was none, and to do so partly in order to abolish slavery.” Organizers presented this thesis through their image selection and description; for example they displayed both the front and back of several cartes de visite. The yellowed cardboard surfaces held handwritten notes, a two-cent stamp, and even Truth’s copyright in its formal bureaucratic language, “Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1864, by Sojourner Truth.” During this time, postage stamps served as an example for the United States governmental transition from coin to paper currency. Truth consistently embedded these critical elements—the implied value of photographs and the accepted value of postage stamps—in this body of work; she printed a commodity that was traded and circulated to further her cause—abolition.

These were objects not just of or about Truth, but authored by Truth. As the curators go on to explain, she was unique and perhaps even forward-thinking in filing a copyright in her own name as sitter, not photographer. This is in contrast to the Frederick Douglass portrait described above that prominently featured “Warren,” the name of the photographer, in embossed script, as the exhibition brochure noted.

Through objects, Grigsby and the curatorial team established a tight history of currency in America and its connection with slavery. The curators never let their audience forget that chattel slavery is a core source of American wealth and that as the country was establishing new boundaries, deciding the limits of states’ rights, and even fighting for emancipation of the enslaved, there was a human cost. Their breadth and boldness were only magnified in a time when the lie of black inferiority was accepted as scientific fact.

There are present-day examples of authorship found in the ubiquity of digital photography; one need only consider our complicated present relationship to selfies, social media, and monetization. If autograph books have become outmoded, the public desire to see and thereby consume society’s celebrities has not. From curated birth announcements (see Beyoncé’s Instagram post of February 1, 2017) to entire books of selfies (see Kim Kardashian’s 2015 Rizzoli published tome Selfish) people, particularly women of color, continue to invent photographic currency. Kardashian, in particular, with her vague skill but very clear success, has made a career, sometimes facilitated through others, sometimes self-authored, of taking images not to sell products, but to sell her image directly to her audience. In contrast to Truth, does she sell both shadow and substance?

These conditions—that of authorship, the politics of black portraiture, capital, and its reach into the ever-refreshing feeds of the present—make Truth’s cartes de visite, and by extension the exhibition, radical.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1598

PDF: Clay – Sojourner Truth, Photography, and the Fight Against Slavery

About the Author(s): Jackie Clay is Director of the Coleman Center for the Arts, York, Alabama.