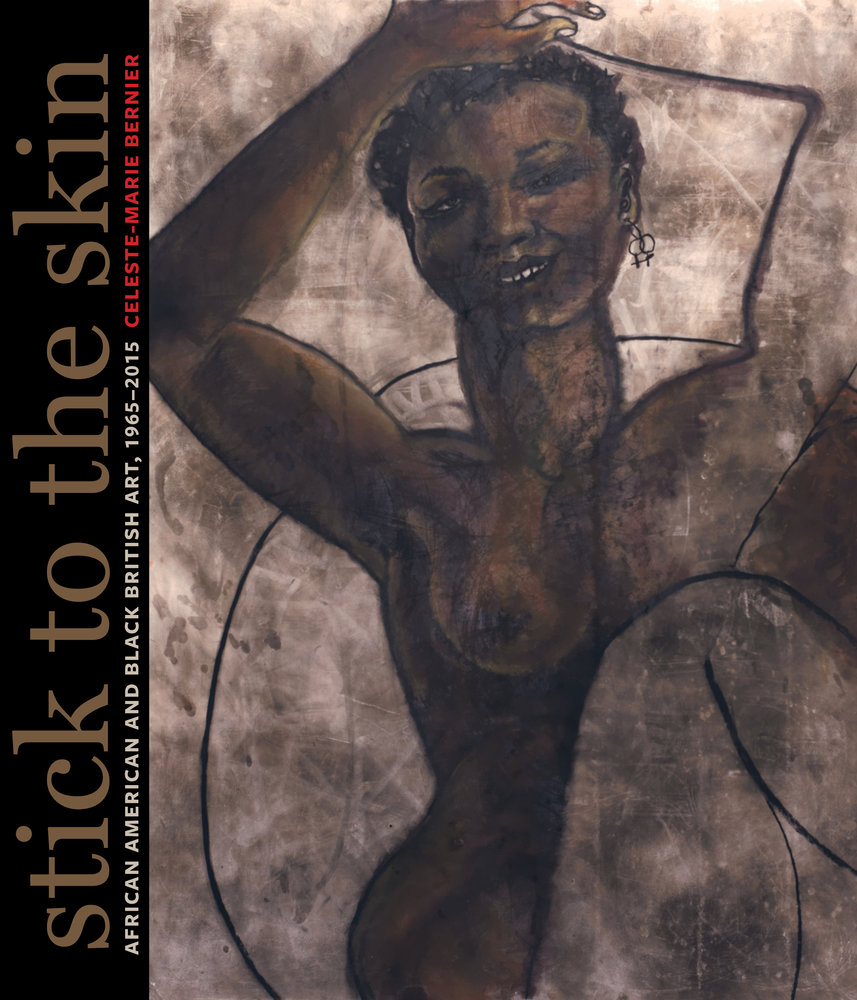

Stick to the Skin: African American and Black British Art, 1965–2015

by Celeste-Marie Bernier

by Celeste-Marie Bernier

Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. 344 pp.; 99 color illus. Hardcover: $85.00 (ISBN: 9780520286535)

In this hefty volume, Celeste-Marie Bernier presents fifty short essays on contemporary African American and Black British artists in pursuit of an “alternative critical language and a new scholarly framework” (2); however, the book is also “a warning that we are not there yet” (xii). She argues that the fifty artists included seek out what Black British painter Donald Rodney describes as a “Black lexicon of liberation,” or a method of resisting the subjugating forces that exclude and silence the voices of Black artists across the diaspora (xi). The phrase “Black lexicon of liberation” undergirds the author’s close readings of artwork, in pursuit of an “alternative visual framework,” that register iconographies of slavery and resistance, from martyrdom and tragedy to overthrow and activism, as well as subversive tricksterism (xii). Examining works from 1965 to 2015, Bernier mines the personal accounts and archival records of African American and Black British artists—a challenging task, as systematic neglect has made for incomplete and lost archives—and she directly critiques the biases of art institutions and scholars alike who often equate an artist’s lack of exhibition history or art-historical mention with low quality or cultural insignificance. Despite the “interpretive quicksand” represented by the respective shapes of Black British and African American art histories, Bernier identifies within both “a commitment to debating issues related to Black bodies, memories, histories, and narratives” (5). She adapts the phrase “Black absent presences and present absences” (addressed in chapter eight) to describe these lacunae in the art-historical record, the recognition of which animates this book’s radical intervention in art history and visual culture.

Relying on the binary framework of presence and absence, however, can eclipse important matters of discursive engagement. It is true that Black artists, due to systematic exclusion and discrimination, have been left out, and from the sidelines have therefore developed experimental and radical practices. But they are also active agents within the public sphere, who sustain conversations with other artists, whether Black or non-Black, whether directly or through influence. Bernier’s repeated assertion that artists are victims of “invisibilizing and marginalizing forces” casts them more often as victims than as agents. The volume is organized into twelve chapters whose titles, each quotations from an artist, project direct or indirect suffering, whether experienced through “invisibilizing exclusion” or direct physical trauma, as the shared foundation that links Black artists in the United Kingdom and the United States.1 These two qualities—a reliance on binary frameworks that assume the reader’s understanding of what white racism means, and an overt association of Black art with trauma and victimization—complicate the goals of this effort.2

This project is less a definitive survey than an unfixed and admittedly incomplete scholarly resource intended to inspire future research in the arts of the African Diaspora, but it prioritizes “analysis, investigation, excavation, and theorization” over definitive canonization (5). The author’s admission of the project’s inherent shortcomings and its pragmatic limitations of scope and content is refreshing, although some conventional gestures would be clarifying, such as what the author means by the term Black, and why the book spans the particular period of 1965 to 2015. What Bernier’s ambitious book acknowledges and performs is that ambitions are by definition difficult to achieve. For example, the author’s aversion to canon-building yields close readings that overwhelmingly center motifs of slavery, trauma, and resistance at the expense of acknowledging the world in which the artwork exists, and the broader cross-cultural web of its entanglement. And although this text excavates and investigates, its promise of theorization remains only partially fulfilled: theory is often directly bracketed out of analyses (a relief to some readers), and at other times is needed (making some essays feel thin and repetitive). Prioritizing excavation and investigation, this text is suitable for readers who seek a point of departure for additional research, or examples of a close reading, but it does not offer an innovative art-historical method or illuminate for readers how the “hidden histories” exposed in each artist’s work relate to each artist’s present ambitions and broader achievements.3

Bernier opens the preface with a discussion of Claudette Johnson’s Woman with Earring (1982; Collection of Lubaina Himid) Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Cargo of Middle Passage (1989; Estate of Rotimi Fani Kayode), and Renee Cox’s Do or Die (1992)—one of the book’s most successful comparative studies, I would argue, because the artists’ practices are kept in consistent dialogue over some pages. Combining a close reading of a single work of art with selected quotations from artist interviews and secondary essays, Bernier reads Fani-Kayode’s Cargo4, a self-portrait, as “a surrogate memorial to missing bodies, histories, and narratives that have been whitewashed out of existence by the Middle Passage” (xv). Bernier interprets what the artist has described as his work’s “imaginative investigation of Blackness, maleness, and sexuality” in terms of a “radically revisionist visualizing back to the Middle Passage as a site of unmemorialized lives and deaths” (xvi). Indeed, this is supported by the artist’s quotations. But the image of the artist’s body, filtered by dark red hues and seated in a fetal position with his hands over his eyes against a dark background, is also in obvious dialogue with Robert Mapplethorpe, whose photographs of black male nudes the artist has described as a major influence. Despite the resonance between Cargo and Mapplethorpe’s Ajitto series, made earlier in the 1980s, the latter is not mentioned here. It is an odd omission, especially since Mapplethorpe clearly trafficked in some of the representational tropes that Fani-Kayode critiques, and the example provides a compelling context for Bernier’s reading. Here, as in the other essays, she writes with an emphatically artist-centric viewpoint, wholly focused on the individuals whose practices are grounded in “radical resistance and arts of imaginative remembering,” even when comparative examples would strengthen her claims (xvii).

For the transatlantic comparative study this claims to be, historical context is instructive terrain on which to build one’s house: what is it about the late 1980s, for example, that led Fani-Kayode, Cox, and Johnson to envision the Black body in the ways that they did? What global systems link the concerns and constraints of these disparate artists?5 Stick to the Skin illuminates only the latter of two realities: that the mainstream art world is structured by legacies of Eurocentric racism, and that Black British and African American artists make work in resistance to those forces. To assume that readers understand the cultural machinations of white supremacist agendas enough to contextualize Bernier’s pursuit of a “Black lexicon of liberation” requires a significant leap of faith. The terms and phrases “white supremacy,” “white-inflicted atrocities and abuses,” and “commodified white racist fantasies of ‘Blackness’” are not broken down or explained (xii; xv); this oversimplification risks alienating some confused readers and, worse, reinforces a flattening, binary understanding of racism as existing solely between Black and white people, rather than in its intra-racial, complex, and nuanced realities. Moreover, the author’s emphatic focus on Black artists’ engagement with trauma, racial violence, and the brutal history of slavery—at the expense of a more fulsome reading of their practices—also suggests that Black artists do not create work for purposes of joy or humor, for their own sake.

In 2013, this book project had a different working title: Imaging Slavery: The Body, Memory and Representation in Fifty Years of African American and Black British Visual Arts 1960–2010—and indeed, it is in focusing on slavery and its representation where the author excels. Her essay “The Slave Ship Imprint” expertly analyses the motif of the slave ship across a range of African American and Black British artists’ practices.6 Here, though, the enigmatic title of “stick to the skin” suggests broader discourse on the body, epistemology, or even theory, which would include but also extend beyond racial violence. Disappointingly, it adheres solely to the traumatic aftermaths of slavery, and other aspects about the book’s framing remain either unaddressed or consciously dodged by the author, who regularly reminds the reader of the book’s inherent limitations. At the outset, she writes: “any attempt to establish a canon of artists only succeeds in colluding with oppressive systems that excluded African diasporic art-making traditions by spuriously trading in politically, ideologically, and racially loaded terminology surrounding illusory constructions of ‘quality’ and ‘importance’” (2). And yet, the publication of such a book, and its tireless advocacy for the importance of these artists’ bodies of work, does develop the beginning of a new canon, one whose dynamically lateral structure knits together Black British and African American art practices through a frequently referenced “Black lexicon of liberation.”

Ultimately, the author’s confrontational posturing in relation to white supremacy reveals more dead ends than pathways through it. In a belated disclosure of positionality, deep into the first chapter, that might explain this, Bernier identifies herself as a “’reluctant’ representative of a ‘firmly Anglo’ culture” who is committed to resisting Eurocentric theory in her book (32). But some theorization, even a theoretically informed space-clearing gesture, might help—take as an example Aruna D’Souza’s book Whitewalling: Art, Race, & Protest in 3 Acts, in which she clearly defines what she means by the expansive neologism “whitewalling”: “the literal site of contention, i.e., the white walls of the gallery; the idea of ‘blackballing’ or excluding someone; the notion of ‘whitewashing,’ or covering over that which we prefer to ignore or suppress; the idea of putting a wall around whiteness, of fencing it off, of defending it against incursion.”7 I admire Bernier’s willingness to retreat from the position of absolute authority that authorship so frequently assumes, and to decentralize within art history the conventional notions of value whose determination is rooted in inequality. Avowing to resist colluding with the oppressive systems that have done harm to African diasporic traditions, she forcefully places the voices of artists in the foreground, and it is theirs that rise over hers. Without a history to tell, however, or a defined rationale for the book’s periodization, and with little acknowledgment of the contemporary context of the artists and objects, Bernier’s text reads as a collection of short essays, some of which verge on extended artists’ statements in their proportion of quoted content. This is unfortunate, since it not only decontextualizes artists’ voices but also comes at the expense of the author’s own thoughts, interpretations, and voice, resulting in somewhat awkward prose. So many other voices are quoted that the author fades into the role of narrator and guide. This retreat, combined with what feels like redundancy in thematic interpretations, leaves the reader feeling inundated by content. The author overextends numerous phrases whose repetition throughout the book dulls their edge: frequent mention of “naming and shaming,” “bearing witness,” “visualizing black to” and “doing justice to” hidden histories, for example, serve to emphasize key frameworks, but they also veer away from the specific into vague platitudes.

In discussing the work of Noah Purifoy, Bernier writes: “Purifoy’s scrap metal pieces are potent signifiers for missing histories, stories, and bodies, taking to task the exclusionary practices of a white art world” (67). Despite its critical tone, this statement still places at the center the “white art world” as a racist boogeyman (how do these sculptures take these exclusionary practices to task, precisely?). Moreover, the essay fails to acknowledge significant information about the artist: Purifoy’s training as a designer, his success in this predominantly white industry in Los Angeles, and his decisive turn away from that industry (this point was incisively made in the exhibition Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada, held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2016). The sculptures Sir Watts (fig. 1) and Sir Watts II (1996; Oakland Museum of California), Bernier argues, “eulogize Black masculinity,” yet at the same time “Purifoy resisted any hagiographic exultation of an archetypal Black heroism, and simultaneously refused to reduce Black bodies to emblems of martyrdom” (68). Several quotes by the artist appear in these paragraphs, but none support the author’s interpretive claims (Purifoy discusses the assemblage as a pun, and how intuitive juxtapositions of material informed his abstract representation of the human figure). Nowhere in Purifoy’s direct words is it clear that “the piece questions white supremacist language surrounding honor, chivalry, and manhood as the domain of whites only, and interrogates a racist imaginary that undergirds and justifies ritualized killings of Black subjects, by radically reconfiguring medieval symbolism to eulogize Black masculinity” (68). By contrast, in her discussion of the same works, art historian Kellie Jones acknowledges Watts’s knight as a symbol for people in battle that “would have growing resonance with the wounded body of the Vietnam War veteran and activism against that conflict” and situates the work within the specific environment of 1960s Black Los Angeles.8

As it stands, the book may have been better served by its earlier title, which more accurately describes its contents.9 Bernier all too consistently states that the artists are addressing the brutalities of transatlantic slavery in different and experimental ways—but experimental how and in relation to what standard? There are no comparative illustrations of what images the artists are resisting, leaving uninformed readers to speculate about (or worse, never recognize) what “atomized, spectacularized, and commodified white racist fantasies of ‘Blackness’” look like (xv). Ideally, readers should know what Bernier means by this, but she unwisely assumes that her audience is on the same page about such highly contested and debated issues as whitewashing, white racism, and the white mainstream.

As a scholar of Black studies and English literature, Bernier focuses on the “writings, thoughts, and imaginaries of women, children and men living and dying in the African Atlantic world,” working on “ideas of artistry, activism, and authorship, and what that means in terms of suffering, sacrifice, and survival.”10 In Stick to the Skin, she focuses on how “Black artists have staged multiple resistances by any and every means necessary to do justice to the imaginative inner lives of Black women, men, and children. They visualize black to body-and-soul-destroying traumas and tragedies by telling the untold—and unimagined, because previously unimaged” (xi). For all of Bernier’s close readings of objects, we learn surprisingly little about historical moments that give rise to these objects, which might build a better scaffolding for a comparative framework, and there is no direct engagement (beyond a brief literature review in the introduction) with how the creative theorizations of Black studies have shaped the field of art history. If historical context matters little in the creative practices represented in Bernier’s study, some theoretical justification is needed to understand what about them eludes the historically specific (radical reimaginings of time and space abound in recent works by Black studies scholars).11 Bernier’s strength in these short essays is in her understanding of the iconography of slavery, racial violence, and resistance to antiblackness—though, curiously, the term “antiblack” does not feature in the text at all. Instead, the “racist white art world” persists as an undefined straw man throughout the text to the extent that it feels almost performative. For the book’s proclaimed audience—students who want to learn about artists of the African diaspora between the United States and Britain, and for researchers who might identify exciting new projects—this unspecified enemy of Black artists’ work should be more clearly and carefully defined if future scholars are to partake in resisting it.

This text is of utmost importance for its thoughtful compilation of artists’ voices, many of which are introduced to broad audiences for the first time through large-format illustrations, although the balance of illustrations is uneven and a few smaller, more comparative illustrations would serve the book well. It also touts its originality as the first comparative study of African American and Black British artists, answering calls by art historians of both fields for art-historical analysis that connects artists across the diaspora more meaningfully. Oddly, the author does not articulate her comparative method, suggesting that the combinatory structure of the book, whose chapters examine the works of three or four African American and Black British artists, is the method. Each chapter begins with a brief introductory section discussing the thematic, technical, or material connections among a group of artists ranging in number from three to nine, followed by a separate short essay on an individual artist. But these groupings, neither grounded by a clearly stated comparative methodology nor a theoretical framework, read as linked primarily by how their artwork illustrates the chapter title. Additional historic, sociopolitical, or exhibition-related links might lend more cohesion to the book. Essential to any reader are the book’s three initial essays, which lay out a broad constellation of forces that have shaped the space that this book has been summoned to fill. In lieu of a bibliography, which would be too large to accommodate, Bernier refers readers to a nearly thirty-page bibliography published in Kalfou, which contains useful archival information.12

In conclusion, Stick to the Skin establishes important thematic connections between artists, and it surfaces many artistic practices across the diaspora that have been long underexplored. Artistic communities, networks, and collectives are not discussed in much detail, but Bernier succeeds in making unfamiliar practices familiar to a broad audience, and offers up the fruits of her extensive research for future scholarship.

Cite this article: Ellen Tani, review of Stick to the Skin: African American and Black British Art, 1965–2015, by Celeste-Marie Bernier Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10828.

PDF: Tani, review of Stick to the Skin

Notes

- “The white supremacist stranglehold exerted by oppressive power structures born of slavery, colonialism, and empire has created social, political, historical, and cultural contexts of Black art production that have ensured that common threads emerge.” See Celeste-Marie Bernier, Stick to the Skin: African American and Black British Art, 1965–2015 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019), 33. ↵

- Bernier’s most lengthy literature review, and methodological model, is Lucy Lippard’s Mixed Blessings: New Art in a Multicultural America (New York: The New Press, 1990), 31–33. ↵

- For art histories that weave extended discussions of individual artists into a cohesive cultural-historical framework, see Lisa Farrington, African American Art: A Visual and Cultural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) and Richard Powell, Black Art: A Cultural History (World of Art), 2nd ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002). ↵

- Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Cargo of Middle Passage, 1989. Gum bichromate print, 12 x 8 in. Photograph © Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst, https://www.revuenoire.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/RFKayode_Nigeria_021-1500×0.jpg. ↵

- See Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain, ed. David A. Bailey, Sonia Boyce, and Ian Baucom (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005). ↵

- Bernier, Celeste-Marie. “THE SLAVE SHIP IMPRINT”: Representing the Body, Memory, and History in Contemporary African American and Black British Painting, Photography, and Installation Art.” Callaloo 37, no. 4 (Fall 2014): 990–1022. ↵

- Aruna d’Souza, Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts (New York: Badlands Unlimited, 2018), 9. ↵

- Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 82. ↵

- The change perhaps acknowledges competing volumes that explicitly focus on the iconographic domain of the slave trade, such as the publication from a year prior: Cheryl Finley, Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018). ↵

- “CSREA Spotlights: Dr. Celeste-Marie Bernir,” The Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America, Brown University, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-v23gV1Qtvw. ↵

- For examples, see Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019); and Michelle Wright, Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). ↵

- See “A UK–US ‘Black Lexicon of Liberation’: A Bibliography of African American and Black British Artists, Artworks, and Art-Making Traditions” in Kalfou: A Journal of Comparative and Relational Ethnic Studies 5, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 172–210, https://doi.org/10.15367/kf.v5i1.207. Many of the bibliographic references are in URL form (websites for artists and their galleries) that may prove challenging to locate over time. ↵

About the Author(s): Ellen Tani is A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Washington, DC