The Girl Behind the Counter: Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones and the Modern Shop Girl

For Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones (1885–1968), the first decade of the twentieth century brought recognition and praise for her depictions of working women. While a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1902–1909), studying under the noted artists William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) and Thomas Anshutz (1851–1912), she was lauded by critics, earned several commissions, and received numerous awards. Major American museums acquired her paintings, and in 1908, one critic called her “the find of the year.”1 Like her fellow Philadelphian Ashcan realists did, Sparhawk-Jones strove to render the authenticity of modern urban life with loose brushwork in journalistic fashion. Her quick, broad, almost abstract brushwork—seen in a work such as The Shoe Shop (1911; fig. 1)—distinguished her from her peers and was repeatedly noted in reviews of her work. The painterly canvas portrays shop girls assisting two fashionable women in the shoe section of a modern department store. Contemporary reviewers praised her paintings as “full of action, so broadly and freely painted” and noted that such qualities “are surprising for the work of a woman.”2 While Sparhawk-Jones captivated critics with her novel brushwork, they largely ignored her equally modern and surprising subject matter. More recent scholarship, such as the biographical account by Barbara Lehman Smith, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones: The Artist Who Lived Twice, brings some attention to the artist and her career, but a careful analysis and contextualization of her paintings is still notably absent from art-historical scholarship.3

Through her portrayal of the shop girl, Sparhawk-Jones carefully created an image that slides between originality and acceptability. By the early twentieth century, the shop girl had become a symbol of modernity, representing mass consumption and new public roles for women. She had also become a central topic of anxiety for the growing middle class. Journalists, reformers, and novelists alike tried to make sense of this figure that represented a new economic structure and changing class divisions and gender roles. Social progressives used her to show the danger of poor working conditions while also portraying her as sexually available and morally vulnerable. The shop girl was a common figure in popular dime-store novels, short stories in women’s magazines, and popular films and plays; she rarely appeared in the so-called higher arts—literature and painting.4 This lack of representation makes Sparhawk-Jones’s interpretations especially fruitful for study. A focused examination of the artist’s portrayals of the shop girl, alongside an understanding of what that role represented in the early twentieth century, offers a more complicated picture of the working woman and the association of middle-class consumers with her. Sparhawk-Jones’s characteristically unstructured and fractured brushwork celebrates material pleasure through paint and intentionally blurs space, class, and the viewers’ relationship to the shop girl, thereby rejecting a simple categorization of the figure as overworked or morally dangerous. These depictions also raise questions about Sparhawk-Jones’s own position as an elite professional woman artist in the early twentieth century by asking the viewer, then and now, to consider class distinctions among women and their own social mobility.

The daughter of an eminent Presbyterian minister, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in the fall of 1902 at the age of seventeen. She took courses in cast and life drawing and sketching with fellow classmates and close friends who included Alice Kent Stoddard, Emily Bishop, Morton Schamberg, and Charles Sheeler. While focusing on “day life” courses, she concluded her studies in 1909 with one “night life” drawing course.5 Her most influential instructors were Anshutz and Chase, both of whom encouraged their students to be independent and paint from life. Although she praised Anshutz for giving his students “complete freedom,” she described herself in a later interview as a “student of Chase.”6 Letters exchanged between the two show a close mentoring relationship, and his influence is easily seen in her attention to light and broad brushwork.7

Sparhawk-Jones entered the art world at a time when women artists struggled for recognition and exhibition opportunities, making her quick rise to fame a notable exception. In a photograph taken in 1905, Sparhawk-Jones confidently poses in her studio, holding a large palette before one of her nursemaid paintings (fig. 2). The artist’s accomplishments are meticulously documented in a scrapbook she kept from 1903 to 1913.8 Between newspaper clippings, letters, short congratulatory notes, bills of sale, reproductions of her artworks, and invitations, she copied verses of poetry by Walt Whitman and excerpts from Leo Tolstoy’s philosophy of art. We learn that the academy commissioned Sparhawk-Jones to paint a large canvas to be hung in the school’s “girl’s lunch room” in 1905. The Market (fig. 3) is a panorama with three scenes of women shopping and bartering in an open-air market, and even at this early date it reveals distinctive fluency in the brushwork. A synthesis of influences, as in the market scenes of Flemish painter Joachim Beuckalaer combined with the painterly technique of Frans Hals, the work offers a nostalgic view of a European food market, with women selling cabbages, pumpkins, and onions. The celebratory scene of commercial exchange foreshadows her later scenes of shopping in the modern department store.

A few pages later, the scrapbook includes a review from the New York Times that highlighted Sparhawk-Jones’s The Porch (current whereabouts unknown), exhibited in the Pennsylvania Academy 1907 annual exhibition. The reviewer praised the work, which depicts four women relaxing on a veranda, as “the most unforgettable canvas in the show” and claimed she had surpassed her teacher, Chase, who also rendered light en plein air but whose painting “falls quite flat and looks tame and stilted by comparison with the jubilant performance of Miss Jones.”9 Such an assessment must have been thrilling for the young artist. A year later, her painting Roller Skates (current whereabouts unknown) was awarded the Mary Smith Prize, an annual prize intended to acknowledge the work by women exhibiting at the Pennsylvania Academy. In 1909, she was the only American to receive an honorable mention at the annual Carnegie International in Pittsburgh for her painting In Rittenhouse Square, which depicts a nursemaid engrossed in the task of caring for two infants while a woman wrapped in fur strolls by (fig. 4).10 She continued to exhibit with the academy annually even after she graduated in 1909, receiving the Mary Smith Prize for the second time in 1912 for her painting depicting a department store sale counter, In the Spring (fig. 5). Between 1909 and 1912, she made herself known throughout the country with depictions of Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square and Wanamaker’s department store. She priced her paintings competitively, between $350 and $500 each, and even Chase acquired one for his personal collection.11 She navigated the male-dominated spaces of the academy and exhibition venues by portraying subjects that were acceptable for a woman to paint.

Picturing the Department Store

A careful analysis of four paintings, all representing the shop girl, serve as the basis for this discussion. The white marble columns in the background of these paintings identify the locale as Wanamaker’s, the newly relocated and remodeled department store, one of the largest at the time. These paintings portray four different sections of the store. The Veil Counter (fig. 6) shows a salesgirl in action—mouth open in explanation and with netting carefully displayed in her hand. She attempts to negotiate a sale with a visibly distracted customer seated at the counter. Another woman stands with her back to the viewer at right, immersed in examining the netted fabric. The Shoe Shop (fig. 1) captures the energy and chaos of the busy sales floor, with open boxes strewn about with rejected shoes. Sparhawk-Jones visualizes the exhausted, yet patient, young shop girls as they assist middle-class women in trying on various styles of readymade shoes. Shop Girls (fig. 7) pictures three working women behind a department store counter covered with bolts of fabric. Folding, measuring, and cutting the material, they appear to be contently engaged in their common work. Sparhawk-Jones fills the foreground of In the Spring (fig. 5) with artificial flowers for corsages and hat decor, creating a still life out of the merchandise. One pink hat balances on a brass stand, and a wooden chair peeks through piles of discarded artificial flowers from Wanamaker’s annual spring sale. Three shop girls huddle behind the counter while a customer carefully inspects a flower.

Examining these four paintings together, several observations can be made about the way Sparhawk-Jones visualizes and understands the relationship between the consumer and the working shop girl. In all of these scenes, Sparhawk-Jones paints only women, almost always in groups, completely engaged in their work or shopping, unaware of or indifferent to the painter’s eye.12 These are neither panoramic views nor personal portraits. She recreates the abundance and dynamism of these new bustling department stores instead of documenting the goods for sale—shoes, hats, veils, and fabric. The shopping experience is expressed as disordered rather than controlled, and the shop girls seem to have as much agency as the middle-class consumers. The viewer is immersed in these intimate scenes of commodity exchange, unable to focus exclusively upon either the shop girl or the customer. Sparhawk-Jones depicts the shop girl and shopper equally and challenges the middle class to identify not only with the consumer but also the shop girl.

Sparhawk-Jones’s portrayals of the store differ from those made famous by French painters James Tissot (1836–1902) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) in the late nineteenth century. These depictions either objectify the shop girl as though she is on display for the male voyeur or depersonalize her in relation to the consumer. The central woman in Tissot’s Shop Girl (fig. 8), for example, stands inside a ribbon shop holding the door for the viewer, who assumes the position of a customer leaving the shop. Unlike the women depicted by Sparhawk-Jones, she meets the viewer’s gaze. A man with a top hat peers in from the street, eyeing another woman working behind the counter. Our view of him is obstructed by a corseted dress form, which mirrors the form of the shop girl inviting him into the store, thereby intermingling the object for sale with the shop girl herself.

Degas’s At the Milliner’s (fig. 9) portrays the salesgirl as subordinate to the middle-class consumer. The full-length mirror partially obscures the shop girl while it frames the woman trying on the hat, thereby rendering the salesgirl anonymous and emphasizing her inferior position. In her analysis of Impressionist depictions of consumerism, Ruth Iskin convincingly argues that Degas’s modiste series has been misunderstood as sexualizing the milliner and shop girl.13 If not sexualizing her, Degas still objectifies and detaches her from the scene. Sparhawk-Jones portrays both the shop girl and the consumer as anonymous, bringing them together in an intimate space. She focuses on the transactions between the consumer and shop girl in the large department store, celebrating modern commercial exchange. Tissot and Degas, in contrast, never painted the department store and instead portrayed small boutiques that deemphasize the economics of buying and selling.14

Sparhawk-Jones was a participant in a broad cultural conversation about gender, class, and commercial display in urban centers in the United States. As Rebecca Zurier argues in her analysis of Ashcan painting, public urban culture created an environment where city dwellers were not only constantly seeing but also reading one another.15 Her work was certainly influenced by the work of Robert Henri, John Sloan, and William Glackens—all alumni of the Pennsylvania Academy—although Sparhawk-Jones was never formally associated with the all-male group that debuted in 1908 as The Eight at an exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in New York. Many of the Ashcan circle gained their reportorial outlook from their experience as newspaper illustrators, yet women were not afforded such an opportunity. As art historian Betsy Fahlman reminds us, “so much of what is central to The Eight—the establishment of private clubs to study the nude model, late nights in the studio accompanied by drinking, the easy camaraderie, and general high jinks—were areas of art student life in which women’s participation was sharply circumscribed because of societal strictures regarding respectable behavior.”16 While women were not given membership to the “Ashcan club,” exclusion did not prevent them from contributing to this imagery.17 A younger group of female artists produced scenes of women’s leisure, most notably Theresa Bernstein, known for urban scenes of theaters and parades, and Ethel Myers, who made small sculptures—caricatures of New York society women and urban types.18 These artists, along with Sparhawk-Jones, had to carefully choose their modern subjects, since urban vision was associated with a masculine gaze.19 Sparhawk-Jones became adept at traversing the male-dominated art world, one where scenes of urban life became synonymous with modernity, by choosing scenes that were considered appropriate.

Sparhawk-Jones painted public spaces she knew well: Wanamaker’s department store and the park at Rittenhouse Square. She lived with her parents on Pine Street, a block or two from the park, and passed near the department store on Market and Thirteenth Streets daily on her walk to and from the Pennsylvania Academy. In a letter written by the artist’s sister shortly after Sparhawk-Jones died in 1968, Margaret recounts Elizabeth’s “remarkable visual memory.” “She never worked from models outside of the classes at the academy, but I can see her now sitting on a bench beside me in Rittenhouse Square, looking so closely at everybody that passed by.”20 Sparhawk-Jones scrutinized her subjects from the sanctioned spaces of the public bench or the shoe department. While both spaces offered a view of America’s growing urbanism, it was the department store in particular that came to represent modern American capitalism and the new role of women as worker and consumer. The department store was frequently portrayed in advertisements and popular literature as a space of desire and aspiration. For both the middle-class consumer and the working-class shop girl, the space of the store and the material goods inside provided the illusion of upward mobility. The department store, along with mass magazines and dime novels, were sites of identity formation for American women of various classes.21

Sparhawk-Jones paints the department store as a distinctly feminine space, demonstrating familiarity and comfort with it. Her frequent use of pastel hues and the incorporation of floral bouquets into fashion and store decor amplify the association with femininity. The department store was very much part of the urban metropolis designed for commodity consumption and public display, but unlike the sidewalk or the park, it was organized to appear as a domestic space by appropriating the atmosphere of a middle-class home with lounges, tearooms, art galleries, and libraries.25 A journalist writing in 1910 exaggerated this point: “Buying and selling, serving and being served—women. On every floor, in every aisle, at every counter, women. . . . Simply a moving, seeking, hurrying mass of femininity, in the midst of which the occasional man shopper, man clerk, and man supervisor, looks lost and out of place.”26 The store blurred what were once clear-cut boundaries between domestic and public space. With the department store pictured and coded as feminine,27 Sparhawk-Jones could safely participate in a larger dialogue around growing urbanism and capitalism. She was free to see and read modern life within the store setting.

Many scholars have argued that this new consumerist space had important liberating qualities, providing middle-class women with a unique public space for participation in modern life. In her analysis of the department store, architectural historian Louisa Iarocci claims that authors writing at the turn of the century understood the space as a feminine domain, “an organizing structure by which everyday problems in ‘domestic comfort and economy’ can be resolved,”28 while men became lost in the maze of mirrors and consumer goods. Mica Nava explains that the space “opened up for women a range of new opportunities and pleasures—for independence, fantasy, unsupervised social encounters, even transgression. . . . And in addition, it provided a spectacular environment in which to stroll aimlessly, to be a flâneuse, to observe people, to admire and parade new fashions.”29

Sparhawk-Jones renders the department store as a comfortable locale for modern female workers and their clientele, yet the gazes of the consumer and the shop girl are not fixed for observation, nor is the space rendered as an organizing structure. Her canvases deny the viewer the controlled gaze of the flâneuse as theorized by Iarocci and Nava. Tissot and Degas viewed the shop girl in either a sexualized or detached way, but Sparhawk-Jones is both observer and participant in these scenes of commercial exchange. Her figures are absorbed in the labor of selling and consumption, and they never look directly at the viewer. Sparhawk-Jones’s figures are pictured like the flâneuse theorized by Anne Friedberg, who suggests that the female consumer does not have the same physical mobility in the store as her male counterpart does on the street. Friedberg instead argues that the store enabled what she calls a mobilized and virtual gaze, as the consumer is distracted by the multiple views leading them to browse from one display to the next.30 Like the many views in the store, Sparhawk-Jones’s lavish, loose brushwork makes it difficult to isolate the subject matter, to scrutinize or study it. Everything is in motion.

Viewing these paintings is not so unlike the experience of shopping. Like the electric lights shimmering on plate-glass windows and the colorful displays on the countertops, Sparhawk-Jones seduces us with her art. As the viewer stands before The Shoe Shop, for example, she witnesses a complex interplay between layers of paint and repetition of color. It is easy to overlook the shoe shopping and instead focus on the orange that highlights the hair of the shop girl at right, or the sumptuous pink that adds rouge to her nose and lips, and creates shadow on her white blouse (fig. 11). Her painterly canvases transmit light and color that flicker in and out of focus, leading from one figure to the next. The artist does not call attention to the material objects themselves—the various styles of shoes. The facture of the painting calls attention to the materiality of the paint and canvas itself. It is difficult to isolate the objects in this painting. Is that floral hat behind the column on a display hook, or is another customer wearing it? The fluid lines draw the viewer closely into the works: lingering and getting lost in the brushwork and the sensuous color. Sparhawk-Jones does not just report information but also recreates the pure pleasure of looking, a pleasure that is both thrilling and tiring. Ultimately, these canvases are not just engaging with the modernity of mass-produced goods in the department store but also the excitement and fatigue of shopping, from both sides of the counter. She suppresses the details to recreate the lively and exhausting space. She pictures work: the work of the shop girl, the work of the consumer, and even the work of the painter. Just as Linda Nochlin read into and suggested the laboring of the artist in Berthe Morisot’s rendering of the wet nurse who cared for her daughter, the labored brushwork reminds the viewer that the painting was manufactured by Sparhawk-Jones herself.31

The Shop Girl in Context

Sparhawk-Jones’s attention to the shop girl engaged in a larger dialogue around the figure at the turn-of-the-twentieth-century. As historian Susan Benson explains, the term “shop girl” was originally a British one used early in the nineteenth century and “conjured up visions of an inferior class position, poor taste in dress and speech, and possibly a low moral state.” 32By the 1890s, the shop girl had also come to represent upward mobility, urbanism, and opportunity. She was both ubiquitous and a modern novelty, growing in number in the United States from approximately eight thousand in 1880 to fifty-eight thousand a mere ten years later.33 The selling staff of the typical American department store was overwhelmingly young, female, single, uneducated, and from the working class.34 The staff was hired to match the ethnicity of their clientele, yet they were likely immigrants, or daughters of immigrants, living on meager wages. Immigrants from Scandinavia, the British Isles, Germany, and Russia were most represented. Jews were frequently employed, while African Americans almost never were.35 These young ladies worked mostly on their feet, behind counters, at cash registers, assisting customers and tidying merchandise, earning between five and seven dollars for what was often a sixty-hour workweek.36 Younger women sold less expensive goods—shoes, veils, hats, fabrics—such as those pictured by Sparhawk-Jones.37 Overworked and underpaid, they found it difficult to please either their customers or their employers. Shop girls were asked to be both subservient and assertive. They were expected to understand the language and manners of the middle class while still knowing their own, more lowborn position.

The shop girl was a type that embodied the liminal position of the independent modern woman and servant to the middle and upper classes. Their uncertain standing, between the factory worker and the department store customer, might best be expressed in the fictional reaction to the shop girl in Theodore Dreiser’s novel Sister Carrie, from 1900. Carrie, who works in a shoe factory, understands her own social position in comparison to the shop girl—“wherever she encountered the eye of one it was only to recognize in it a keen analysis of her own position. . . . A flame of envy lighted in her heart.” 38 The scholarship dedicated to the historical and social condition of the shop girl emphasizes her in-between position. As Benson explains, “Department-store selling had a thoroughly ambiguous status. On the one hand it involved behaving as a servant to the customer, being exposed to the public in a way most distressing to those who believed that a woman’s place was in the home, and being tarred with the brush of immorality. On the other, it offered upward mobility, glamour, and white-collar respectability.”39 Catherine Driscoll makes a similar case in her analysis of the shop girl. Like Benson, Driscoll dwells on her transitional position, calling her both worker and consumer, domestic and not.40 In her examination of the department store shop girl, Lise Shapiro Sanders claims that the shop girl personified the fantasy of consumer mobility at the turn of the century, with the shop girl effectively positioned “between classes.”41 She is working class, unable to afford the latest fashions she sells, and yet she must know those styles thoroughly and speak the language of the middle class. With a seemingly unlimited supply of fashion and trinkets, the department store worked to both emphasize and blur these class distinctions between patrons and workers. The shop girl was reminded on a daily basis of what she could have while never gaining the means to have it. She represented the instability of class relations and the fluidity of public and private realms. She was active and passive—both facilitator and object of consumption.

Bringing further attention to the liminal position of the shop girl, Sparhawk-Jones also makes a point of blurring the distinction between the shop girl and her patron. The salesgirls and their customers all appear of similar age and ethnicity, with similar facial features and hairstyles. The postures and manners of the figures fail to signal class difference, and the customers are often awkwardly positioned. The woman in The Shoe Shop hikes up her skirt as she is fitted for a shoe, and the lone customer in In the Spring slumps improperly over the glass counter. By 1900, most department store shop girls were required to wear black and white to set themselves apart from the customers.42 This dress code is portrayed in all four of the canvases, yet frequently the patron is also wearing white, which makes it difficult to distinguish class differences. For example, the edge of the shop girl’s white blouse in The Shoe Shop bleeds into the white dress of the customer being waited on by another worker to her right. Hats and gloves became the most easily recognizable signs of respectability, as shop girls were never permitted to wear either in the store.43 Yet the standing customer on the left is noticeably without gloves, leaving only the decorated hat to differentiate the two types. As with her brushwork, Sparhawk-Jones used physiognomy, clothing, and pose to blur and resist popular cultural stereotypes that distinguished the shop girl from the shopper.

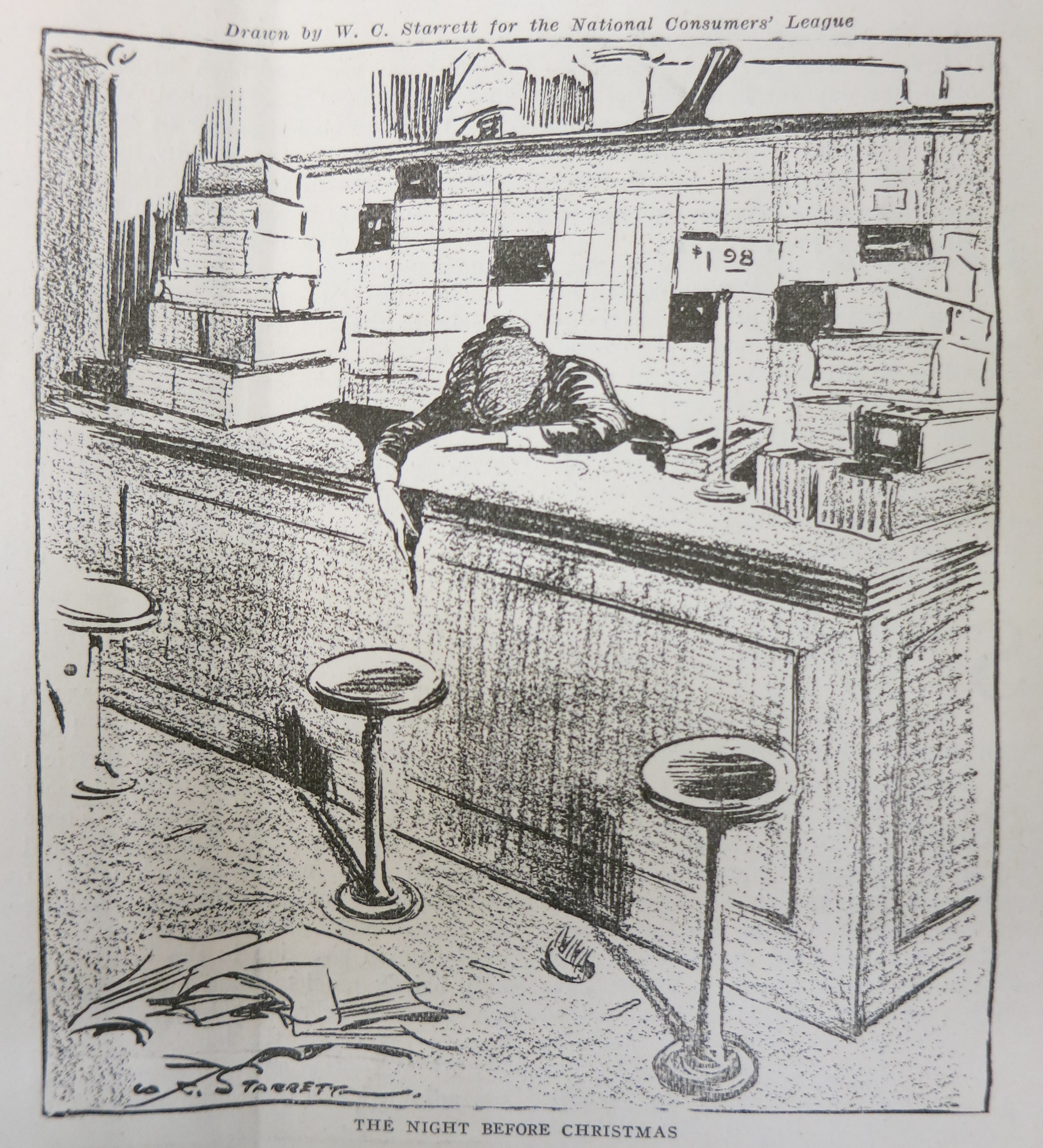

The shop girl was understood to be a particularly exploited type at the turn of the century.44 Progressive, upper-class social reformers, journalists, and suffragists worked to expose unfair working conditions in essays, exposés, and letters.45 Many of these publications suggest that the position of the shop girl was hopeless. For example, Mary Maule’s “What is a Shop-Girl’s Life,” published in World’s Work, records an endless cycle of worry and weariness in her description of the routine: “Standing behind a counter all day waiting on bargain-hunting women, they come home at night, nervous and tired, to be confronted by the problems of food, of clothes, of rent, of board.”46 Anne O’Hagan’s “The Shop Girl and Her Wages,” published in Munsey’s Magazine, follows the daily life of two teenagers working in a New York department store, Nellie and Yetta, and provides a detailed account of their workday and living conditions. These girls, she concludes, represent the class of those “who go down in ruin, physical or moral—those whose conditions succumb to the strain of work.”47 Rheta Childe Dorr went undercover as a shop girl in the handkerchief department for a week, reporting in Everybody’s Magazine about fifteen hour workdays that paid a mere six dollars in weekly compensation.48 Dorr recalls the frustration of folding and tidying the merchandise, only for her neat stack to be disrupted minutes later. She also explains the complex power dynamics involved in persuading a purchase, the delicate balance between manners and determination. The fragile mental state of the shop girl was also portrayed through illustrations in popular journals and newspapers. In one image, “The Night Before Christmas,” published in The Survey (fig. 12), a young woman has succumbed to the pandemonium of the Christmas rush and collapsed with her head on the counter, boxes piled high and papers stacked on the floor. In the short story The Great Wrongs of the Shop Girls, Beatrice is so overworked that she is eventually committed to an insane asylum.49

The shop girl was also seen to be especially vulnerable to sexual exploitation and prostitution. Mary Cranston’s report for World Today, “The Girl Behind the Counter,” warns that with temptations of unlimited merchandise and male clientele, she was constantly tested. She claims that “the moral question is the gravest one which comes to the department store girl.”50 Louise Bowen’s The Department Store Girl, a book based on interviews with two hundred shop girls, laments the many different expectations of the shop girl profession. The department store girl, she says, “is much more subject to temptation” than the girl who works in the factory. She goes on to claim that the shop girl encounters two kinds of dangers: women and young men who will lure and recruit her to a “disreputable home” (brothel) and managerial men who make advances that the salesgirl cannot refuse, lest she lose her job.51

Sexual vulnerability was sometimes sensationalized in fictional accounts. The prototype was established in Émile Zola’s 1883 French novel Au Bonheur des Dames and reinforced through American and British popular plays, musicals, films, and dime-store novels that tell a similar story. The wholesome shop girl with polite and refined manners moves socially upward through marriage, following the trajectory of Denise in Zola’s story, or she falls into debt after falling prey to the daily seduction of fashionable trinkets, inevitably leading her to prostitution and ruin. This is the overarching lesson in many popular stories of the time, such as O. Henry’s short story “The Trimmed Lamp” (1906).52 O. Henry tells of Nancy, a shop girl, who learns the grace and manners of the upper class in the department store and quickly seeks out a millionaire husband. In the end, however, she finds true love with an honest working-class man, revealing the superficiality of commodity goods. In her analysis of the turn-of-the-century shop girl, cultural historian Erica Rappaport explains that popular plays and musicals often portrayed the salesgirl as capitalizing on her good looks and sexuality for social mobility. Looking at “Shop Girl” (1894), “Only a Shop Girl” (1904), and “Girl Behind the Counter” (1906), Rappaport writes, “the shop girl never remains a worker. . . . At some point in the play, she usually changes places with an upper-class shopper,” most often through marriage.53 Lois Weber’s film Shoes (1916) presents a more cautionary tale. Eva, an underpaid shop girl, is forced to prostitute herself to afford a new pair of shoes, which she needs to keep her job behind the counter. Viewers of Sparhawk-Jones’s paintings would certainly recall these sensationalized stories published in popular journals and portrayed on stages and screens. Yet her depictions do not reinforce these caricatures.

Sparhawk-Jones counters popular perceptions of the shop girl as both capitalist victim and morally vulnerable waif with depictions of young women busily occupied in the daily routines of the sales floor. Her canvases, which often feature pairs or trios of working women, show a particular sympathy for their working conditions. She emphasizes the mundane labor of folding fabric, organizing boxes, and attending to shoppers. The girls’ faces exhibit intense concentration. She also highlights the fatigue of a shop girl’s work by including chairs, a reminder that the customer was invited to rest during a day of shopping, while shop girls were reprimanded for such a break. With subjects absorbed in work, Sparhawk-Jones resists a simple objectification of the shop girl as capitalist victim, thereby shifting the conversation toward the complicated class relations existing in a female-dominated space.

The complexity of the shop girl’s position of subservience and authority was likewise discussed and debated in period journals and popular stories. A 1910 publication, Types from City Streets, characterizes the shop girl as pretentious: “One of the essentials of success is to appear successful. Insincerity is a necessary element of material progress.”54 Artificiality was emphasized and portrayed in fictional accounts of the shop girl as yet another moral obstacle to overcome. Shop girls were also commonly portrayed as uneducated, rude, and overly aggressive. In Rupert Hughes’s novel Miss 318 the assertive salesgirl, Miss Mooney, is fired by her male supervisor and replaced with a more naive, beautiful, and polite version of herself. Hughes emphasizes Miss Mooney’s lower-class class origins by writing her dialogue in dialect, with exaggerated slang. One article geared toward store managers noted that overly familiar forms of address were insulting: “The salespeople have become so forward as to call customers ‘Dearie.’”55 Yet the Ladies Home Journal, in an essay, “She Is Paid for It,” asks shoppers to consider the stressful position of the shop girl, suggesting that they can learn “self-control, courtesy, forbearance, and poise” from the best of them.56

Sparhawk-Jones’s portrayal of the working woman focuses on the interpersonal social relations between the two classes, offering a glimpse of the shop girl’s complicated relationship with her middle-class female clientele. From the other side of the counter, the shop girl facilitated the consumer’s desire for goods on display. The customer relies on the shop girl’s knowledge of the goods for sale, the latest fashions, inventory, and sizes. Shop girls must know their patrons intimately, measuring their bodies and reassuring them with compliments, ones that might be taken as insincere. Yet they are strangers. The Shoe Shop best captures these intimate and often uncomfortable moments. One shopper, the wealthy woman at left wearing a purplish suit, elaborate hat, and stylish jet bead tassel pendant, looks down to inspect a new shoe, directing our gaze to the salesgirl, who also looks down at the shoe. Kneeling in a subservient position, the shop girl is careful not to look directly at her customer. The scene on the right shows a similarly intimate exchange as the shop girl appraises the sizing of the customer’s shoe; again, their eyes meet only at the shoe. The Veil Counter emphasizes similar class barriers. Despite the shop girl’s earnest attempt to sell a veiled hat, the customer looks away, completely distracted by another scene in the store or immersed in her thoughts. In the Spring shows a fashionable customer wearing white gloves seated along a glass vitrine and carefully inspecting an artificial flower. Separated by the glass counter, three shop girls huddle together to gossip or strategize a sale, excluding the customer from their conversation.

The complexity of class difference in the department store is reinforced through Sparhawk-Jones’s compositions, which separate the shop girl from the viewer. The lushness of these canvases asks the viewer to intimately engage with and immerse oneself into the paintings. Yet, the artist simultaneously isolates the viewer from her working-class subjects with the repeated use of visual barriers, spatial devices such as counters, columns, and benches. Iarocci calls department store counters the “physical manifestation of class and gender that separate the rich from the poor.” 57 Likewise, Sparhawk-Jones uses counters in The Veil Counter and In the Spring to separate the shop girl from her clientele. The shallow composition in Shop Girls drops the viewer into the scene of measuring and folding fabric, but the counter keeps the viewer on the other side, prohibiting her from interacting with the busy workers or even seeing their facial expressions.

Sparhawk-Jones blurred the differences between the shop girl and the shopper that are found in popular portrayals, thereby denying the viewer an obvious point of identification, whereas other artists—such as Alice Barber Stephens (1858–1932) and William Glackens (1870–1938)—clearly differentiated them. Appearing on the cover of Ladies’ Home Journal in September of 1897, Stephens’s The Women in Business, one of a series of works with this title, painted in grisaille for mass printing, likewise depicts Philadelphia’s Wanamaker’s department store (fig. 13).58 However, here the women are starkly separated in terms of class, a separation sanctioned by the moralizing addition of a stained glass window in the distance. The canvas is divided by the sales counter, which accentuates an exchange between a fashionably attired seated woman, who appears relaxed, and a shop girl standing rigidly behind the counter. The woman, accompanied by a well-groomed black dog, carefully inspects the displayed linens with her elegantly gloved hand. The salesclerk drops her gaze, ensuring no direct eye contact. Stephens adds two children positioned along a diagonal. A well-dressed child with a bonnet stands alongside her mother in the left distance, while a young shop assistant of similar age, with tired eyes, walks toward the viewer in the lower right foreground. As Rena Tobey suggests, “Stephens’s emphasis on the poor child forces the viewer to consider the economic system that creates such disparity, while the affluent child almost blends into the background, minimizing her importance.”59

Sparhawk-Jones similarly separates the working and middle classes with a counter but declines to direct the viewer’s identification toward one or the other. The artist emphasizes the lighthearted camaraderie enjoyed by the workers in In the Spring, what Benson calls a “clerking sisterhood,” an alliance made by salesgirls to increase sales and maintain their sanity.60 Looking at the The Veil Counter, one might sympathize instead with the exhaustion of the seated customer, who seems overwhelmed by the fabric selection, rather than with the aggressive young shop girl who hopes to make a sale. Created for a woman’s journal, Stephens’s portrayal of commercial exchange between the working and middle classes is a much more straightforward rendering, which like the essays written at this time by progressive social reformers asks the viewer to sympathize with the shop girl and work toward improvement in her lot.

Glackens’s Shoppers provides yet another view of the Wanamaker’s store (fig. 14). It was included in the famous 1908 Macbeth Gallery exhibition. The canvas is organized for the male viewer, displaying women as commodities. Situated in the lingerie department of Wanamaker’s New York branch, middle-class customers pose wearing fashionable fur coats and plumed hats. Unlike Sparhawk-Jones’s anonymous figures, Glackens includes his wife Edith, the daughter of a wealthy textile manufacturer, in the central portion of the canvas, inspecting some lace fabric without acknowledging the girl behind the counter. Everett Shinn’s wife, Florence, looks directly at the viewer, to invite him into the commercial exchange. Positioned on the far left side of the composition, stooped over and poorly illuminated, Glackens’s shop girl is deferential to her customers. As the title indicates, this portrayal of the department store celebrates the shoppers and the material goods, in contrast to Sparhawk-Jones’s representation of the shop girl’s labor. The Women of Business and Shoppers focus upon and ask the viewer to identify with either the worker, in the case of Stephens, or the consumer, in the case of Glackens. In contrast, Sparhawk-Jones positions the viewer among material goods (shoes, artificial flowers, and fabric) without a clear point of identification with either the shoppers or the shop girls. This mobile gaze offers a more complicated image of social, gender, and economic differences in the growing American city.

Painting Freely

Sparhawk-Jones blurred class difference in her canvases, yet gender differences were clearly coded within the language used to interpret and praise her paintings. Close analysis of this critical rhetoric reveals an active attempt by critics to interpret her style, specifically her free brushwork, as masculine, despite her clearly feminine subjects. Norma Broude argues that gender played a considerable role in how Impressionist paintings were interpreted in critical discourse and carefully exposes a phallocentric reading and dissemination of the style by critics.61 The insistent gendering of brushwork, Broude maintains, reveals a larger cultural anxiety and fear of women painters in the early twentieth century. Kristin Swinth convincingly demonstrates that this gendering was a direct response to the growing number of women in art academies and exhibitions at the turn of the century.62 “Rejecting refinement as too ‘feminine’ and technique as too mechanical, critics called for greater individuality and virility in American art. They praised art that seemed to display ‘masculine strength,’ which they defined in terms of a striking, individual vision and a virile ‘virtuoso’ style.”63 The paintings most highly praised in the early twentieth century were those, as Swinth argues, that “drew attention to the act of painting itself.”64 Sparhawk-Jones’s expressive, painterly style was marketed as modern, decoupling her shop girl subjects from the more popular sentimental stories published in women’s journals.

Sparhawk-Jones’s brushwork was seen as a novelty that distinguished her from other female artists and was repeatedly noted in contemporary reviews of her work. As Sarah Burns has argued in relation to Cecilia Beaux, the language used to interpret Sparhawk-Jones for a larger audience manufactured gender difference. Unlike Beaux, whose style was read by critics as sensitive, Sparhawk-Jones’s brush was interpreted as virile and aggressive, which is “surprising for the work of a woman.”65 Reviews of her paintings described her approach as “free,” “breezy,” and “spontaneous,” words that were directly associated with an independent and energetic masculinity. For example, the New York Times described Shop Girls as “painted with spontaneous gusto.” 66 Referencing The Shoe Shop, one critic wrote, “The paint is tossed about so freely to make a puzzle of the canvas surface.”67 A review of Roller Skates admired its “unaffected, spontaneous gayety” in the “refreshingly breezy canvas.”68 Another critic described her subjects as presented in a “broad, forthright manner.”69 These reviews imply that Sparhawk-Jones’s brushwork is simply instinctive, which was understood to be individual and masculine.

Critics similarly interpreted Sparhawk-Jones’s use of color as bold, intense, and bright, despite her frequent use of soft, lush shades of pink and lavender to portray the fabrics and floral hats in the department store. The discrepancy between the actual appearance of her canvases and contemporaneous descriptions is striking. For example, one critic wrote, “Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones is not at all tonal. Here we find our complete contrast, as she cannot find pigments too bright for her purpose.”70 Another, referring to In The Spring, wrote, “black and white cannot do justice to the radiant prodigality of color values in Miss Sparhawk-Jones’ canvas.”71 Yet another critic wrote that her canvases produce “a shining fanfare of color, a pattern out of which one gradually becomes conscious of the forms.”72 These descriptions of blinding bright colors align with the bold and expressive brushwork, further coding her brush as masculine.

A gendered dichotomy was reinforced by calling her work virile rather than sentimental. Virility was seen as the highest honor in early twentieth-century art criticism and was repeatedly emphasized in reviews of Sparhawk-Jones’s work.73 For example, The Veil Counter was described as “exceedingly virile in treatment.”74 An exhibition review published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer described her work as “realism done with vigor in a modern but truly sane fashion.”75 A critic reviewing In Rittenhouse Square wrote that Sparhawk-Jones had an “individual and vigorous way of seeing her subject.” 76 Critics frequently imagined Sparhawk-Jones’s brushwork almost as a weapon. One critic wrote, “Miss Jones has seized the situation. Her vigorously modeled figures are in motion.”77 In the Spring was painted with “impressionistic strokes as bold as the sword of Jeanne d’Arc.”78 The artist’s brush is equated with the sword that fought for French liberation, carefully coupling her bold brushwork with a feminine icon to soften this masculine rhetoric. At times, critics directly acknowledged the constructed binary between sentimentality and virility and clearly place Sparhawk-Jones on the masculine side. One wrote that she is “against sentimentality in paint,”79 and another critic applauded her detached approach: “she is [an] illustrator” who displays “sentiment without sentimentality.”80 By rejecting emotion, critics signaled that Sparhawk-Jones was a serious painter.

Her brushwork and palette were understood to be individualistic and bold, yet few critics took notice of the modern subject matter Sparhawk-Jones employed. One described the “lavish array of millinery to delight the feminine fancy and deplete the masculine pocketbook.”81 This reviewer takes active consumption away from the woman in the picture and replaces it with her husband’s wallet. It is curious that critics would emphasize a female painter’s virility at a time when aggressive energy was so closely associated with masculinity. Yet by expressing surprise at her virile brushwork, critics downplayed her focus on working women, a subject laden with connotations of class difference in a feminine space. After all, her audience was more likely the middle-class consumer or the department store owner than the shop girl. Like the shop girl, who persuaded her customers to buy, Sparhawk-Jones, with the help of her critics, negotiated sales with her audience.

Even with accolades for her unique, uninhibited brushwork, which brought her commissions, prizes, and inclusion in the collection of major museums, Sparhawk-Jones’s mobility was made difficult. Her subject matter was restricted to feminine spaces, and, most significantly, she was unable to study abroad. She was awarded the Cresson Traveling Scholarship in 1906, which would have allowed her to study in Paris for one year, although she declined the scholarship.82 In a letter from Eleanor Wilson McAdoo to Jessie Wilson Sayre, both acquaintances of the artist, McAdoo informed her friend that Sparhawk-Jones had given up the $2,000 award from the Pennsylvania Academy for study abroad. “True she had to give it up for it was to be used in foreign study and she was debarred from that field, but at least she knew the glory of the victory.”83 Sparhawk-Jones’s biographer suggests that she was forced to decline the Cresson because of parental disapproval of Morton Schamberg, a romantic interest of hers who would be in Paris at the same time.84 Her father died in 1910, and in 1913, her sister Margaret married, leaving Elizabeth as the sole caretaker of her mother, who the artist later described as demanding and controlling.85 Letters in the artist’s scrapbook reveal that she repeatedly turned down opportunities to exhibit her paintings and judge exhibitions during these years, due to family obligations.

Sparhawk-Jones abruptly withdrew from the art scene in 1913, amid repeated requests for travel and exhibitions. She declined an invitation from Robert Henri to exhibit in the now infamous Armory Show exhibition and was hospitalized shortly after.86 In an interview conducted at the end of her life, she recounted, “I broke down because I was overtired, I had done too much in too short a time.”87 Following a decade or so of hospitalization and recovery, Sparhawk-Jones returned to the art scene in the 1930s. Leaving contemporary life behind, she turned inward to paint such universal and poetic subjects as The Dreamer (fig. 15). Although the canvas does not depict working women, The Dreamer still asks the viewer to engage with its subject by creating a lavishly worked surface without a clear narrative. A nude woman lies prone and covers her face to avoid seeing the disturbing visions that surround her. Several winged men in business suits carry nude women above, while at the foot of the dreamer’s bed, another suited man holds a billowing blanket, ready to cover or perhaps smother her. She too, presumably, will be swept into the murky background. Painted with bristle brushes on fine linen in a mixture of watercolor and oil, the canvas appears blurry, as though it were painted under water. Her late canvases no longer depict the gusto of modern, urban life, yet her subjects are no more stable.88 The ambiguity of the scene is heightened by the gestural quality of the brushwork, which creates a striking fluidity between the figure and ground of the painting. In contrast to her early work, the critics interpreted her later paintings as “decidedly feminine,” “emotional,” and “sentimental.”89 These works received favorable critical attention throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and her close friend and fellow artist Marsden Hartley called her a “peculiar mental force” and an “original,”90 yet she has not been written into art history. “Strange that she is not recognized far and wide as among the ablest, most distinguished women painters in the United States,” wrote the critic for American Artist in 1944.91

It is unclear whether Sparhawk-Jones would find her obscurity so strange, because her story is not unique. She was one of many professional women artists at the turn of the century, although few have become part of the historical canon. Sparhawk-Jones gave voice to another forgotten professional woman—the shop girl. Her canvases construct a nuanced depiction of the relationship between female workers and female consumers, where labor, consumption, exhaustion, material pleasure, camaraderie, and subservience mingle and blend together. By depicting the shop girl, Sparhawk-Jones engaged in a topic that interrogated class and gender difference. Through her beautifully seductive, yet socially conscious paintings, she gave both herself and her subjects an agency that they have been thus far denied by history.

Cite this article: Elizabeth Carlson, “The Girl Behind the Counter: Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones and the Modern Shop Girl,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1683.

PDF: Carlson, Girl Behind the Counter

Notes

The author would like to thank and acknowledge Tiffany Johnson Bidler, Sarah Kelly Oehler, Erika Doss, and Sarah Burns who offered helpful feedback at the Newberry Library’s American Art and Visual Culture Seminar. I am also extremely grateful to the anonymous reviewers for Panorama. Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Southeastern College Art Conference and the Midwest College Art Conference.

- Cited in Barbara Lehman Smith, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones: The Artist Who Lived Twice (Parker, CO: Outskirts Press, 2010), 68–69. This article was reproduced in Sparhawk-Jones’s scrapbook, but the bibliographic information is not included. ↵

- James Townsend, “Pennsylvania Academy Exhibition,” American Art News 6 (January 25, 1908): 7. ↵

- Smith began her work after accidentally finding the scrapbook in the attic of a property where she worked. ↵

- While artists associated with the Ashcan group portrayed consumerism, there are still relatively few examples depicting the shop girl. In addition to William Glackens, discussed later in this essay, the American scene painter Raphael Soyer completed a series of paintings depicting shop girls in the 1930s. See Ellen Wiley Todd’s excellent chapter on his imagery in The New Woman Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993). ↵

- Student registration card for Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, Student records, RG.03.03.02, archives of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. ↵

- Ruth Gurin {Bowman}, Oral History Interview with Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, April 26, 1964, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↵

- See scrapbook of Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, Collection of Barbara Lehman Smith. ↵

- Scrapbook, Sparhawk-Jones. ↵

- “Younger Painters to the Fore,” New York Times, November 11, 1907, 5. ↵

- “An American Salon,” The Craftsman 16 (April/September, 1909): 390. ↵

- Bills of sale can be found in Sparhawk-Jones’s scrapbook. Chase purchased the The Veil Counter in 1910 for $350.00. ↵

- Newspapers make mention of more examples picturing shop girls and nursemaids, but these images were likely destroyed. Smith, Sparhawk-Jones’s biographer, tells us that she burned all paintings in her possession around 1916. Smith, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, 100. ↵

- Ruth Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 60–92. ↵

- Aruna D’Souza argues that commercial exchange is rarely depicted by the Impressionists, even though they painted cafés, boulevards, and dance halls. She suggests that those works that did represent the store highlighted anxiety around the growing commercialization of art in the late nineteenth century, as distinctions between the art salon, art gallery, and department store became increasingly blurred. See “Why the Impressionists Never Painted the Department Store” in The Invisible Flâneuse? Gender, Public Space and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris, ed. Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008). ↵

- See Rebecca Zurier, Picturing the City: Urban Vision and the Ashcan School (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 49. ↵

- Betsy Fahlman, “The Art Spirit in the Classroom: Educating the Modern Woman Artist,” in American Woman Modernists: The Legacy of Robert Henri, Marian Wardle, ed. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 102–3. ↵

- For an examination of the modern way of seeing of the Ashcan group, see Zurier, Picturing the City. ↵

- Paula Calvin makes this argument in “New Women as Urban Realist Artists” (MA Thesis, Arizona State University, 2002). See especially Elsie Heung’s essay “The Ashcan School? Theresa Bernstein and Her Vision of New York,” in Theresa Bernstein: A Century in Art, Gail Levin, ed. (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 2013). Bernstein’s positive portrayals of women’s suffrage meetings and parades were exceptions to the kinds of subjects more commonly produced by women associated with the Ashcan movement. ↵

- Griselda Pollock argues that the modern subject and the spatial strategies associated with Impressionism also excluded the female artist, as only the exclusively male flâneur could experience these viewpoints. See Griselda Pollock’s “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity,” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988), 54. ↵

- Margaret Turnbull to Dorothy Spencer, January 18, 1975, Archives of the Des Moines Art Center. Spencer was the curator of twentieth-century art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. ↵

- Katherine Mullin makes this argument in Working Girls: Fiction, Sexuality and Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016). See especially chapter three, “The Ubiquitous Shop-girl: The Thrills and Perils of Selling,” 97–128. ↵

- Using Wanamaker’s as a case study, Richard Leach has examined how American merchants catered to consumers through décor and design. See his Land of Desire: Merchants, Power and the Rise of a New American Culture (New York: Vintage, 1994); see also Jan Whitaker, World of Department Stores (New York: Vendome Press, 2011) and Bill Lancaster, The Department Store: A Social History (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 2000). ↵

- John Wanamaker, Golden Book of the Wanamaker Stores (Philadelphia: Wanamaker Stores, 1911), 277. ↵

- Leach, Land of Desire, 75. ↵

- Sparhawk-Jones might also have frequented the store to visit its seventh-floor “free gallery.” The gallery opened in the 1880s, and by 1911 it had acquired more than 600 works of art, mostly academic in nature, coming directly from Parisian salons. In fact, her teacher, William Merritt Chase was a regular juror when the store hosted art competitions for local grade-school competitions. See Wanamaker, Golden Book of the Wanamaker Stores, 256. ↵

- Rita Childe Dorr, What Eight Million Women Want (Boston: Small, Maynard, 1910), 115–16. ↵

- See especially Lisa Tiersten, Marianne in the Market: Envisioning Consumer Society in Fin-de-Siècle France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Erika Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Iskin, Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting. ↵

- Louisa Iarocci, The Urban Department Store in America, 1850–1930 (New York: Routledge, 2014), 158. ↵

- Louisa Iarocci, The Urban Department Store in America, 1850–1930 (New York: Routledge, 2014), 158. ↵

- Anne Friedberg, Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 32–44. ↵

- In her essay on Morisot’s Wet Nurse, Linda Nochlin argues that Morisot exposes woman’s work through the subject matter itself and the labor of Morisot’s open and worked application of paint. See Nochlin, “Morisot’s Wet Nurse: The Construction of Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting,” in Linda Nochlin, Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper and Row, 1988): 37–56. ↵

- Susan Benson, Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890–1940 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 24. Although published almost thirty years ago, this book is still the most comprehensive historical account of American shop girls. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 23. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 128. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 210. ↵

- Lise Shapiro Sanders, Consuming Fantasies: Labor, Leisure, and the London Shopgirl (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2006), 33. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 242. ↵

- Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie (1900; New York: Bantam Books, 1992), 18. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 210. ↵

- Catherine Driscoll, “The Life of a Shopgirl” in Modernist Cultural Studies (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2010), 90–112, esp. 91–92. ↵

- Sanders, Consuming Fantasies, 3. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 236–38. These dress codes were established in the majority of major departments, including Wanamaker’s. ↵

- Nan Enstad, Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 77. ↵

- Though Sparhawk-Jones does not depict the misery and hardship in the factories that produced the garments and shoes displayed in the store, the scenes of labor might also remind a viewer of strikes and tragedies such as the New York Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. For example, the New York garment industry experienced a five-month strike of 20,000 workers between 1909 and 1910, and the fire, which killed 146 mostly female garment workers, made headlines in March, 1911. See H. Barbara Weinberg, ed., American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765–1915 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 171. ↵

- See, for example, Alice Calvin, “The Shop Girl,” Outlook 88 (February 15, 1908): 383–84; Mary Alden Hopkins, “The Girls Behind the Counter,” Collier’s 38 (March 16, 1912); Mary Van Kleek, “Working Conditions in New York Department Stores,” Survey 31 (October 11, 1913): 50–51. ↵

- Mary Maule, “What is a Shopgirl’s Life,” World’s Work 14 (September 1907): 9315. ↵

- Anne O’Hagan, “The Shop-Girl and Her Wages,” Munsey’s Magazine 50 (November 1913): 259. ↵

- Rheta Childe Dorr, “The Woman’s Invasion,” Everybody’s Magazine 20 (January 1909): 372–85. ↵

- The Great Wrongs of the Shopgirls: The Life and Persecutions of Miss Beatrice Claflin (Philadelphia: Barclay, 1885), 23. ↵

- Mary Cranston, “The Girl Behind the Counter,” World Today 10 (March 1906): 271. ↵

- Louise Bowen, The Department Store Girl (Chicago: Juvenile Protection Agency of Chicago, 1911), 4–5. ↵

- See Rupert Hughes, Miss 318 (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1911) and O. Henry, “The Trimmed Lamp,” in The Trimmed Lamp and Other Stories of the Four Million (New York: Doubleday Press, 1907). ↵

- Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure, 198. ↵

- Hutchins Hapgood, Types from the City Street (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1910), 126. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures, 130. ↵

- Margaretta Tuttle, “She is Paid for It,” Ladies’ Home Journal 10 (October 1914): 21. ↵

- Iarocci, The Urban Department Store in America, 167. ↵

- The Women in Business was one of six paintings in the American Woman series produced by Stephens. The others were The Woman in Society, The Woman in Religion, The Woman in the Home, The American Girl in Summer, and The Beauty of Motherhood. ↵

- Rena Tobey, “Alice Barber Stephens: Emerging Ways of Living and Working,” Art Times (Winter 2014), https://arttimesjournal.com/art/Art_Essays/winter_14_rena_robey/alice_barber_stephens.html. ↵

- Benson, Counter Cultures. See especially, “The Clerking Sisterhood: Saleswoman’s Work Culture,” 227–82. ↵

- Norma Broude, Impressionism: A Feminist Reading (London: Rizzoli, 1991), 8–16. ↵

- Kristin Swinth, Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 3. ↵

- Swinth, Painting Professionals, 132. ↵

- Swinth, Painting Professionals, 153. ↵

- Sarah Burns similarly shows how language constructed Cecilia Beaux as feminine compared to her contemporary, John Singer Sargent. See Sarah Burns, “The ‘Earnest, Untiring Worker’ and the Magician of the Brush: Gender Politics in the Criticism of Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent,” Oxford Art Journal 15, no. 1 (1992): 36–53. ↵

- “Philadelphia Exhibition,” New York Times, February 4, 1912, 12. ↵

- James William Pattison, “The Annual Exhibition of American Art,” Fine Arts Journal 26 (January 1912): 38. ↵

- “Art at Home and Abroad,” New York Times, January 26, 1908, 8. ↵

- “Oh Stop!” Washington Post, February 17, 1911, 6. ↵

- Pattison, “The Annual Exhibition of American Art,” 38. ↵

- Fullerton L. Waldo, “The Pennsylvania Academy,” Arts and Decoration 2 (March 1912): 180. ↵

- “Palette and Brush,” Town Topics: The Journal of Society 61 (May 6, 1909): 16. ↵

- Fahlman, “The Art Spirit in the Classroom: Educating the Modern Woman Artist,” 103. ↵

- “An American Salon at Pittsburgh,” American Art News 7 (May 8, 1909): 2. ↵

- K.K. Kitchen, “New York—Its Babylon, Work Shop, Playground—According to Viewpoint,” {Cleveland} Plain Dealer, February 18, 1912, 6. ↵

- “Palette and Brush,” 16. ↵

- “Pennsylvania Academy,” The Sun, February 12, 1908, 6. ↵

- Scrapbook of Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones. ↵

- “Philadelphia Exhibition,” New York Times, February 4, 1912, 12. ↵

- Jane Dundas, “Chatter of the Studio,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, May 21, 1911, 41. ↵

- “Art in Philadelphia,” The Nation 94 (February, 22, 1912): 196. ↵

- Scrapbook of Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones. ↵

- Eleanor Wilson McAdoo to Jessie Wilson Sayre, July16, 1906. Jessie Wilson Sayre Papers, MC216, Box 1. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. ↵

- Smith, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, 59–60. ↵

- Gurin {Bowman}, “Oral History Interview with Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones.” ↵

- Smith, Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, 97. ↵

- Gurin {Bowman}, “Oral History Interview with Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones.” ↵

- A careful analysis of Sparhawk-Jones’s later works made in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s is necessary for a fuller understanding of the artist’s production and the significance of her work within art-historical scholarship. ↵

- See “Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones,” ARTnews 45 (March 1947): 25; and Leslie Katz, “Three Exemplary Painters,” Arts Magazine 38 (April 1964): 44–47. ↵

- Hartley quoted in Clifford Wright, “Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones: Painter of Romantic Incident,” a short essay written for Rehn Galleries. Frank K.M. Rehn Galleries records, Box 12, Reel 5865, Archives of American Art. ↵

- “She Paints on her Pulse,” American Artist 8 (September 1944): 10. The critic was responding to Sparhawk-Jones’s inclusion in Romantic Painting in America, an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. ↵

About the Author(s): Elizabeth Carlson is Associate Professor of Art History at Lawrence University