The Wandering Gaze of Carrie Mae Weems’s The Louisiana Project

In 2003, the Newcomb Art Gallery at Tulane University commissioned Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953) to create a work in response to the impending bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase.1 Consisting of more than seventy separate photographs and screen prints, a video, and a live performance by the artist at its debut, The Louisiana Project examines both the distant past of slaveholding, antebellum Louisiana, and the state’s recent present, characterized by economic crisis and racial segregation. The Louisiana Project takes as its starting point the ubiquitous New Orleans festival Mardi Gras and the parades and balls associated with the all-white Krewes of Comus, Momus, and Rex—the oldest of the thirty-odd groups who parade through the streets during the annual celebration of Carnival that precedes the Lenten season. The Louisiana Project juxtaposes the secrecy that surrounds the Rex Ball, an exclusive event attended by members of New Orleans’s white upper class, and the not-so-secret sexual liaisons had by the male scions of these elite families with African American women from the adjacent community of the gens du coleur throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

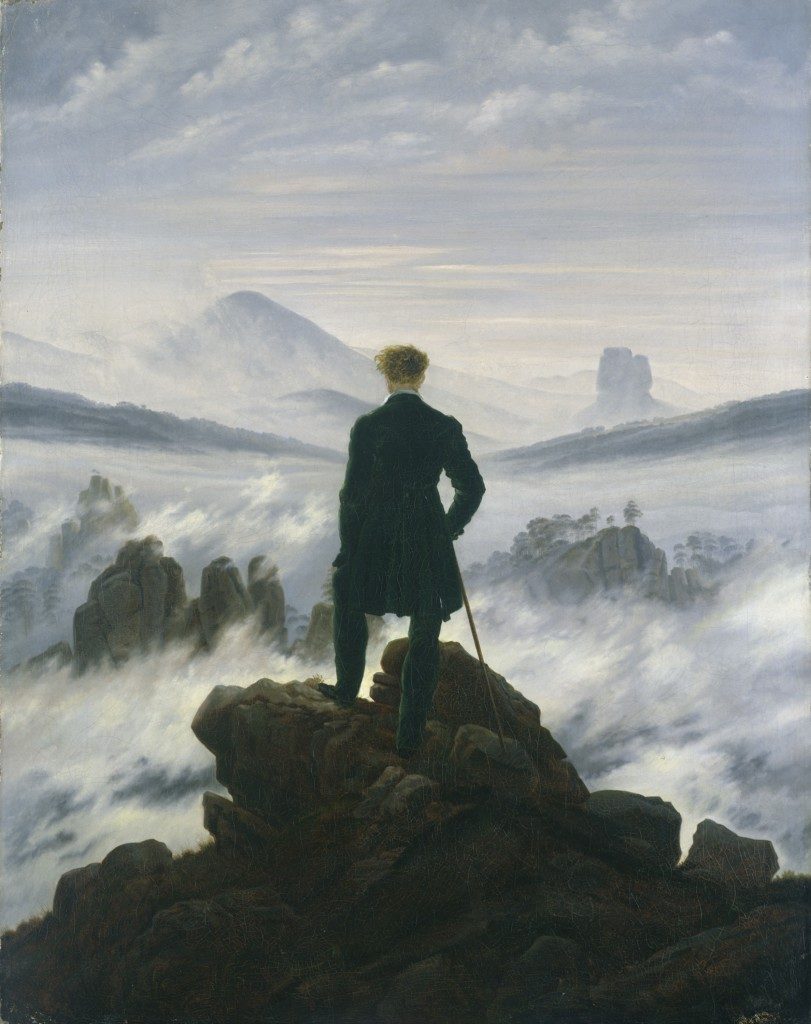

In The Louisiana Project, Weems continues an artistic practice of reinterpreting the facts of history by placing her own body within its extant detritus. In many of the photographs that comprise the project, the artist stands with her back to the camera in front of an architectural edifice, amid a rural landscape, or within a domestic interior (fig. 1). She wears period clothing: a plain, long-sleeved dress that falls to the floor, evoking the daily wear of working-class women in the nineteenth century. In other photographs, in which her body faces the camera, she wears masks and men’s tuxedos (fig. 2). Susan Cahan observes in the catalogue for the project that, “Weems’s focus on masking and facades underscores the notion that social hierarchies result from a differential in relations of power, not birthright.”2 The masks, costumes, and choice to turn away from the camera prompt a reconsideration of the physical presence of history. This paper will argue that by turning her back to the viewer, Weems also engages a long history of visual obfuscation associated with the sublime, a history that may be most powerfully seen in the Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) painting, Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog (c. 1817; fig. 3).

Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog pictures the figure of a romantic wanderer at the top of a craggy peak somewhere in Saxony or Bohemia, looking out over a landscape that is shrouded in mist. With his back turned to the viewer, not only is his identity concealed, but his expression is as well. Is he delighted with the vista or horrified and aghast? His confident pose, with his left foot planted firmly on the penultimate step of the peak and his right side braced with a walking stick, makes him appear unaffected by the strong wind that briskly blows his blond hair to one side. There is little indication of a vertiginous instability, only a sense of mastery despite the seeming insignificance of the lone walker himself.

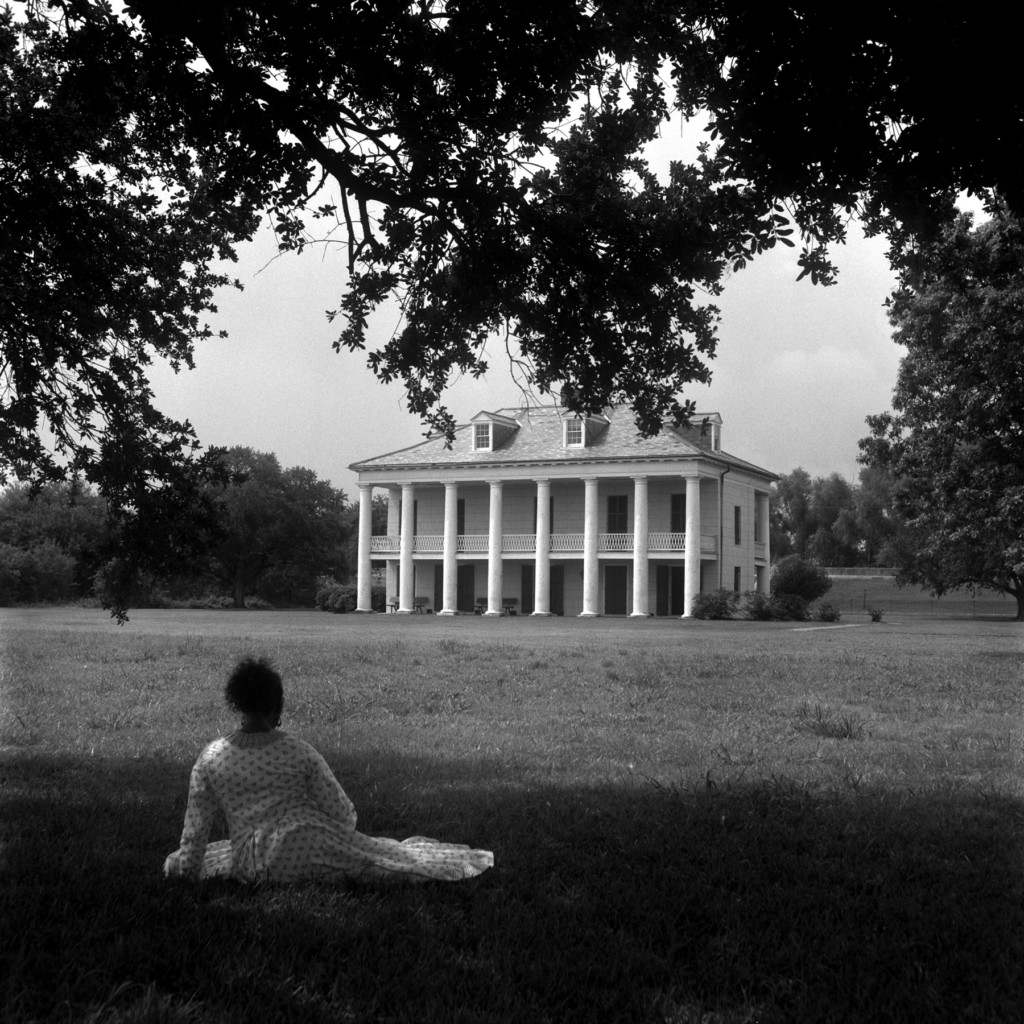

Like Friedrich’s wanderer, we do not have to see through Weems to know what she is seeing. Instead we can see through Weems. Weems prompts us to reconsider our understanding of domestic spaces and architecture as we gaze upon a photograph of her sitting on the grass before a Greek Revival–style plantation home (fig. 4). “Who lived here?” “Who looked out of these windows?” “Who walked these halls?” “Who died here?” “Whom did they love?” “What fate befell them?” This process of what I term a “re-membering” of history through Weems’s body and gaze indicts the landscape and the buildings that populate as key players in multiple histories.3 By seeing through Weems as she moves through space, time, and place, we are privy to visions both real and ethereal. And in these pictures, we see a place that is on the edge of expiration and yet struggles valiantly to hold its own decay at bay.

In his 2004 book The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past, John Gaddis ruminates on Friedrich’s Wanderer in a Sea of Fog, using the painting and its sole figure as a metaphor for the way that we as historians can only represent the past by portraying it as a near or distant landscape. “We can perceive shapes through the fog and mist, we can speculate as to their significance, and sometimes we can even agree amongst ourselves as to what these are,” argues Gaddis. “We pride ourselves on not trying to predict the future, as our colleagues in economics, sociology, and political science attempt to do. We resist letting contemporary concerns influence us—the term ‘presentism,’ among historians, is no compliment. We advance bravely into the future with our eyes fixed firmly on the past: the image we present to the world is, to put it bluntly, that of a rear end.”4 In The Louisiana Project, Weems shows us her backside in order to emphasize her own privilege as the primary holder of vision.

Here, Weems is the revenant among the exteriors and interiors of Greek Revival plantation homes; the disremembered specter standing on a stretch of deserted railroad or traversing above ground tombs; standing still akin to the figure in the Friedrich painting Wanderer in a Sea of Fog, she is always poised on the brink, having come to a sublime vista just a bit too late to find it at its peak. She makes us a witness to the landscape around her. Here, Louisiana has become the object of her gaze; a gaze that reads different visions than those seen by others, apocryphal visions. Through her wandering gaze we encounter a landscape that is oddly predictive, one that in its mix of pasts juxtaposes the slowly evanescing Greek Revival architecture of the 1840s with the decrepit expanse of a mid-twentieth-century public housing project (a sort of postbellum slave quarters). In its poignant repetition of condition, the landscape of The Louisiana Project is profoundly prescient in nature.

A key component of the installation is a video that intercuts television footage from 2003 of Rex, the King of Mardi Gras, dancing with his queen at the Rex Ball, with a shadow drama of characters dressed in eighteenth-century clothes engaging each other in a silhouetted tableau of domesticity, masquerade, and sexual domination. Mardi Gras marks the annual outing of rituals that are both creative and destructive, defining and mystifying, a world in which things are turned on their head on purpose; a world in which transgression is constantly rewarded so long as it follows tradition. By providing the viewer with an “other” way to see Mardi Gras, and the parades of Rex, Endymion, Orpheus, Zulu, and Bacchus, Weems remembers a new Carnival through the age-old tradition of topsy-turvy. Mikhail Bahktin describes this tradition as practiced in pre-Enlightenment Europe as a social institution through which the “temporary suspension of all hierarchic distinctions and barriers among men . . . and of the prohibitions of usual life” was the rule.5 For Bakhtin, “carnivalesque,” the term used to describe the kind of behavior displayed during these periods, is both the description of a historical phenomenon, the activities that took place during the great medieval carnivals of Europe, and the designation for specific literary tendencies, as well as a relation to our understanding of the physically grotesque. Bakhtin viewed such raucous festivities as regulated moments in time when the social authority of the secular and religious authorities was suspended at least momentarily for the ascendance of licensed transgression. Such communally sanctioned, and essentially participatory, festivals of the grotesque and fantastic allow participants to move beyond a regular membership within a crowd to become part of a whole. In this way, to participate in Carnival, and in the case of New Orleans to attend the parades of Mardi Gras, is to become a part of a collective; a collective in transgression. Within Carnival, asserts Bakhtin, “[A]ll were considered equal. . . . Here, in the town square, a special form of free and familiar contact reigned among people who were usually divided by the barriers of caste, property, profession, and age.”6 Carnival, and its progeny, the Mardi Gras of New Orleans, both construct and deconstruct the social rules that govern transgression and trauma.

The visual drama of Weems’s video is accompanied by an audio track of the artist’s voice slowly reciting a detailed poem of remembrance. The combination of audio and video work to conjure up a world of faded majesty remembered beneath a veneer of deceit that evokes Louisiana’s complicated and uneasy mythic legacy of race and gender. Weems has inserted herself as a real and figurative witness to the romantic tales that we tell ourselves about slavery and interracial sexuality in the Creole South: tales about the voodoo priestess Marie Laveau and Labelle’s “Creole Lady Marmalade,” tales that veil the legacy of enslavement and the conflicting truths about interracial sexual liaisons in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.7

Of all the myriad elements of The Louisiana Project, it is Weems’s solitary Friedrichian wanderer and the physical constancy of the landscape in which she moves—a landscape that is as much a constructed character as the ones that Weems creates and embodies—that hold the pain of the past and the possibility of a future. I argue strongly for the project’s prescience, for its ability to help us envision the future through visions of the past, and for its oracular gift to see the reflexive nature of the present in relation to history. The Louisiana Project transforms Weems’s body into a vehicle through which we are made to see, and at other times a body that we are made to see through. This task of specular transcendence is accomplished through images that posit the artist’s physical presence in the picture plane as a momentary and yet ever-present imprint upon time and space, so that representations of many pasts and recent futures can be seen from multiple perspectives. In this way, her body and the landscape in which she moves are made to hold the past and the pain of our individual and collective trauma of enslavement, as well as the historical blindness that has affected our understanding of the past, present, and possible futures of Louisiana, and especially New Orleans, just two years later, following the traumatic experience of Hurricane Katrina.

To experience The Louisiana Project, in which Weems constantly positions herself as a witness to both past and future histories, is to be confronted by one’s own position as a viewer and to acknowledge the ever-present power of the gaze and the perpetual struggle by women artists, in their work and in their persons, to control it. Much of Weems’s work during the past three decades has been about controlling the gaze, from The Kitchen Table Series of 1990 (fig. 5)—in which we are asked to virtually join the artist and her models at one end of a table as silent witnesses to dramatic domestic events that unfold over a series of photographs—to The Jefferson Suite from 2001, where our spectatorial presence is elided and rechanneled as we consider the ramifications of genetic research in relation to race, ethics, and morality as well as the American judicial system.

In order to control both the narrative and the gaze, Weems enters her own work through a process of self-objectification. In The Jefferson Suite, we see the artist in several guises, but most strikingly in the role of Sally Hemings, the enslaved consort of our third president, Thomas Jefferson. In The Jefferson Suite, Weems served as her own model, a role that she has frequently inhabited in her work. Alternately dressed as Hemings and also undressed as an example of a genetic topos, Weems functions as focalizer for a visual tale of sexual attraction, political intrigue, and social deception that leads the viewer from the eighteenth century through to the 1998 revelation of the Jefferson DNA study that scientifically demonstrated the connections between the black Hemings and the white Jefferson families. Weems collapses time and space in The Jefferson Suite and rechannels the authority of voice into the body of one whose enslavement had imposed a loud silence in history. By juxtaposing this staged photograph with a more natural one of our forty-second president, William Jefferson Clinton, and his much younger mistress, White House intern Monica Lewinsky, Weems encourages our gaze to wander across a historical legacy of unequal power relations and sexual attraction that span more than two hundred years of American history. In The Louisiana Project, Weems continues the practice of inserting herself into a truly apocryphal version of history. In this way, Weems mobilizes what I call a “wandering gaze.”

As an art-historical theory of spectatorship, the gaze has its origins in film theory and the work of Laura Mulvey. Mulvey’s 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and the Narrative Cinema” introduced the gaze as a theory of gendered, spectatorial differences in popular twentieth-century film that help to explain the ways that men and women view the world and each other on screen.8 Mulvey asks that we imagine a darkened movie theater in which every member of the audience has their eyes locked on the screen. All vision follows the cone of light that travels from one side of the theater to the other, from the projection booth to the screen. In this scenario, Mulvey places an active male viewer seated in the theater and a female image on the screen. It is a kind of perennial geometry through which male vision consumes the female image. In the past thirty-plus years, much has been written to dispute Mulvey’s argument that cinematic vision is posited as male and heterosexual. Feminist film scholars including B. Ruby Rich, Teresa de Lauretis, and Linda Williams have since argued that the relationship of female viewers to the screen image is less patriarchal and more dialectical.9 They argue that the female viewer retains more agency through a selective filtering process. Williams encourages a questioning of “the orthodoxies of a classical spectatorship without abandoning the fundamental [importance of] the spectators who gaze at [film], glance at it, or avert their eyes from it.”10 Rich pushes back a bit more firmly against the dominance of gaze-based Lacanian psychoanalytic feminist film criticism, charging it with an unblinking ahistoricity that fails to account for “the key determinants of context, audience, or even aesthetic fashion.”11 Similarly, de Lauretis argues the importance of “engaging all of the codes of cinema . . . to articulate the conditions and forms of vision for another social subject” as a way to broaden the possibilities for the “production and counterproduction of social vision.”12 The idea that the only person who could be interpolated into the subject of the gaze, the primary person who could be called forth to be the “gazer,” if you will, would be a man whose sexualized vision would contain the female object on the screen in an unequal power relation, is simply not tenable when you begin to think about the multiplicity of points of vision that are possible in a contemporary, expanded viewing environment. Simply put, there are multiple points of view. Weems’s wandering gaze allows multiple individuals to occupy the position of power as the holder of the gaze, regardless of gender identity, sexual orientation, or race.

With the wandering gaze, we can allow ourselves the freedom to move into an expanded field of vision. If we begin to conceive of visual art as unbound narrative, we can read images as connecting not only to a past, but also a present, and a future as well. In this way, we begin to see how a multifold increase in the diversity of vision would inform the interpretation of the moment of viewing in more complicated ways than those provided for by the simple assumption of a uniform, heterogeneous, white world; a world in which the ability of class, ethnicity, and education to separate whites from one another is ignored and sublimated beneath a brittle veneer of pink-skinned sameness.

The wandering gaze allows us to step inside the skin of Friedrich’s omniscient white viewer, who, above the mists, commands the landscape below him. We are aware of our own significance, standing astride the peaks of history, and our utter insignificance as one of many who has risen to consciousness only to fall. We not only dominate our field of vision, but we also falter in its sublimity, which proves to diminish our standing. What is offered by an expansion into the wandering gaze is an ever-more inclusive theory of vision in which myriad spectators, regardless of race, gender identity, or sexual orientation, can be the empowered agents of their own pleasure and (I would argue) their own pain, experiencing vision as an ever-widening field of subjective choice and experience. In this way, multiple identifications are possible.

Increasingly, we are better able to grasp the association of power with various raced and gendered positions in society and see how a multifold increase in the diversity of vision would inform the interpretation of the moment of viewing in more complicated ways and allow for multiple identifications.

And it is this type of viewing, that of gazing back at the past from the perspective of the present, that The Louisiana Project opens for its audience. Weems’s photographs push us to recognize that you can see through me and you can see through me, regardless of my original position or yours. After all, all forms of knowledge are channeled through our experience as individuals within specific cultural moments; as the artist allows his or her work to move out into the world, it is constantly (re)interpreted through each individual act of viewing.

The photographs of The Louisiana Project, rather than being the result of a single visualization, present multiple visualities. In this expanded visual and temporal field we begin to see that in The Louisiana Project, vision is embodied in the wandering gaze as an intervention into the meta-narrative, creating a number of differing histories beyond the present and into the past and into the ever-present, yet ever-changing, landscape. However, such an approach requires that the viewer not be lured into the notion that Weems the narrator is the same person as Weems the model, for these images and those she has created previously in The Kitchen Table Series or The Jefferson Suite are not unbidden snapshots or autobiographical records, but instead are staged images in which the artist has assumed a role that is of her own conception and creation. It is not Carrie Mae Weems the narrator who stands in the doorway of a Greek Revival plantation house with her back to the camera. That Weems stands outside the photograph, in the role of what Mieke Bal would call the visual focalizer, initiating and directing vision into the distance.13 We are view-pointed by her, to her, and through her, and we see the land beyond the building. She is the intercessor through whom we come to know the landscape of the past in a new and different way.

Through the wandering gaze of The Louisiana Project, we are able to see the relation of trauma to the visualization of memory, and the act of forgetting or refusing to see in relation to our irrevocable separation from the Lacanian notion of the real.14 To view The Louisiana Project is to see the (un)dead New Orleans of the past, a world that is no more and yet resists erasure through the reassurance of ritual. The Louisiana Project creates a space for the dramatization of individual and collective memory, a space in which personal and communal trauma is shared. Through these multiple points of focalization that Weems’s wandering gaze marshals, viewers become open to the multiple narratives that are possible within the spaces of her address. Domestic architecture is no longer home so much as it is place, a place in which reanimated bodies move though a landscape and architecture that is eternal and ever changing, enacting relationships that are predicated on social structures at once remote and yet wholly familiar. It is the scene of the crime, and Weems’s presence in it is as much accusation as it is reflection. As our wandering gaze is focalized through that of Weems, we see New Orleans as a matrix of communities afloat in the wake of an antebellum history of enslavement, a postbellum product of segregation, and, in the contemporary moment, a city still marked by post-Katrina displacement, creative resurrection, and creeping gentrification. To view and re-view The Louisiana Project is to see the future through visions of the past, and through this oracular gift, to see the ever-reflexive nature of the present in relation to the past.

The act of prescient reconstruction and stitching back together of the past, affected by Weems’s wandering gaze, brings into focus terrestrial revenants to cloud our vision like the mists before Friedrich’s wanderer. In the absences, in the vacated landscapes that endure both before and beyond, we may reflect on the roles we ourselves have played in the past, in the present, and in the future.

Cite this article: Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “The Wandering Gaze of Carrie Mae Weems’s The Louisiana Project,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1629.

- Carrie M. Weems, Susan Cahan, and Pamela R. Metzger, The Louisiana Project (New Orleans: Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University, 2004). ↵

- Susan Cahan, “Carrie Mae Weems Reflecting Louisiana,” in Weems, Cahan, and Metzger, The Louisiana Project, 7–16. ↵

- I have argued elsewhere, most extensively in Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), for a type of transgressive, creative artistic practice that repositions and “remembers” the authoritative voice of history. In this way, artists such as Walker and Weems remove the dominant narrative from its position of mastery by “remembering” it via a privileging of alternative facts and experiences taken from a subaltern position and location. In this practice of reinterpretation, memories are formed and reformed, revealing purposefully or actively “disremembered” histories. My use of the terms “remember” and “disremember” are taken from Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), in which the protagonist uses them to describe strategies for psychological survival following the traumas of enslavement. ↵

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 2–3. ↵

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1984),15. ↵

- Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 10. ↵

- For more on the woman known as Marie Laveau, see Martha Ward, Voodoo Queen: The Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004). The song “Lady Marmalade,” about a Creole prostitute, was written by Bob Crewe and Kenny Nolan in 1974 for the group Eleventh Hour. It was later popularized by the group Labelle, featuring Patti Labelle. ↵

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (Autumn 1975): 6–18. ↵

- See B. Ruby Rich, Chick Flicks: Theories and Memories of the Feminist Film Movement (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998); Teresa de Lauretis, Figures of Resistance: Essays in Feminist Theory, ed. Patricia White (University of Illinois Press, 2007); and Linda Williams, Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995). ↵

- Williams, Viewing Positions, 4. ↵

- Rich, Chick Flicks, 292. ↵

- De Lauretis, Figures of Resistance, 34. ↵

- W. Bronzwaer, “Mieke Bal’s Concept of Focalization: A Critical Note,” Poetics Today 2, no. 2 (1981): 193–201, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1772197 (accessed March 16, 2018). ↵

- For Lacan, our relationship to a natural state, a state of the real, is lost once we enter into the practice of language. For more, see Tom Eyers, Lacan and the Concept of the Real (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012). ↵

About the Author(s): Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw is Associate Professor of History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania.