Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto’s Queer Futurity

Tina Takemoto’s experimental films are infused with a historical consciousness that invokes the queer gaps within the state-sanctioned record of Asian American history. This essay examines Takemoto’s semi-narrative experimental film, Looking for Jiro (fig. 1), which offers complex encounters of queer futurity, remaking historical gaps into interstitial spaces that invite and establish queer existence through both imaginative and direct traces of representation. Its primary subject, Jiro Onuma (1904–1990), is a gay, Japanese-born, American man who was imprisoned at Topaz War Relocation Center in Millard County, Utah, during the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans by the United States government during World War II.1 Takemoto’s title, Looking for Jiro, alludes to Isaac Julien’s lyrical black-and-white 1989 film, Looking for Langston, which is a pioneering postmodern vision of queer futurity, reenvisioning the sophisticated, homosocial world of the Harlem Renaissance and its sexual and creative possibilities for writers such as poet Langston Hughes (1902–1967).

Over a five-year period, Takemoto developed a speculative series of responses to Onuma’s archive that account for a varied set of interventions: the film itself, a group of sculptures based upon those found in the archive, and, lastly, a journal article about the process, in which they reflect:

While Japanese American history and LGBT American history are two cultural and political legacies that most significantly shaped my own identity formation as a queer person of color, the struggles against the racial injustice of wartime incarceration remained separate in my mind from the challenges facing LGBT Americans during the pre-Stonewall era of the 1940s and 1950s. Common sense tells us that among 110,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans, some of them were LGBT individuals. Nevertheless, seeing Onuma’s photographs from Topaz startled me. . . . They opened my eyes to the presence of LGBT individuals in the American concentration camps and connected me to this history of wartime imprisonment in a whole new manner.2

Takemoto was introduced to Onuma’s life story at San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, where his archive resides, which become the basis for Looking for Jiro and later instantiations of artwork. Reduced to a single, slender box, Onuma’s personal effects contain a homoerotic collection of muscle and fitness photographs and postcards, including a training course with Earle Liederman, a New York bodybuilder who wrote books about weightlifting and ran a proto-personal training business during the 1920s and 1930s, which entailed sending exercises to students, including Onuma, via United States mail. Takemoto undertook ongoing artistic research using Onuma’s papers. The resulting output reflects upon, memorializes, and honors his history and presence as a gay man imprisoned at Topaz, a man whose assigned camp role was in food service as a mess hall worker.

The film is a musical theatrical soliloquy in which Takemoto performs as Onuma; its scenes all take place after hours in a darkened mess hall as Onuma cleans the floor. Looking for Jiro debuted at MIX New York City: 24th New York Queer Experimental Film Festival in 2012 and was subsequently continuously screened on the queer film circuit.3 In their films, Takemoto creates fictive spaces fused with archival footage and cultural specificity as a means of reexamining prewar Japanese American communities, the communal trauma during their World War II–era incarceration, and its legacy and aftermath at the dawn of overlapping 1960s ethnic, racial, and sexual liberation movements, largely centered in California.

Takemoto lives and works in California: they are a greater Bay Area native; a longtime San Francisco artist, scholar, and activist; and dean of humanities and sciences at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, where they have taught since 2003. The primary interlocutor for their own practice, Takemoto received an MFA at Rutgers University, studying there with Martha Rosler, a PhD at the University of Rochester in visual and culture studies under Douglas Crimp, and they publish and lecture widely on their artistic research. Takemoto is also a fourth-generation Japanese American whose own family experienced wartime incarceration.

The official timeline of Chinese, Japanese, and Pacific Islander immigration is chronicled through the social apparatus of nineteenth- and twentieth-century recordkeeping: birth and death certificates, marriage licenses, and applications for and denials of citizenship. This is followed by the specificity and precarity of second-, third-, and fourth-generation experiences deeper into the twentieth century, by next-wave immigrants: displaced Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian refugees. Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, initiated a sordid chapter in American history in which Japanese American citizens were subject to racist maltreatment at the hands of the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Between 1942 and 1945, one hundred and twenty thousand Japanese American citizens were classified as enemy aliens, forced from their homes and communities, and incarcerated in remote detention camps with squalid living conditions for the remainder of the war.

In addition to anti-Asian racism, the midcentury era was also rife with antigay legislative actions, including the enforcement of sodomy laws and trumped-up obscenity charges leveled at suspected homosexuals, then known as the homophile community. As historian Whitney Strub reminds us, the 1940s and 1950s were perpetually unsafe spaces for anyone homosexual, or who was so represented. The 1944 G.I. Bill formally excluded gays and lesbians; the proliferation of sodomy laws in cities nationwide criminalized gay men and characterized them as perverts under the guise of safety for women and children; and Executive Order 10450, signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953, officially classified homosexuals as security risks, immediately terminating their federal employment and job security and curtailing their presence and visibility for decades thereafter.4 Sandwiched between the passage of Executive Order 9066 in 1942 and Executive Order 10450, Onuma’s life story is circumscribed and limited by the tyranny of the nation-state.

Time Goes By, So Slowly

One of the conditions for self-transformation and fantasy in musical theater is when a character experiences solitude that leads to self-discovery; versions of this are plentiful in mainstream Broadway musicals: “At the Ballet” in A Chorus Line (1975), or “I’m Changing” in Dreamgirls (1981). In Takemoto’s film, Onuma finds himself alone at the end of a long work shift. His evening is repurposed, seized by queer epiphany: the broom becomes a microphone and the dining hall becomes a stage. In his quest for agency and sexual self-expression, he performs a mash-up of the campy ABBA disco hit, “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” (1979) and Madonna’s “Hung Up” (2005). Hung Up’s bassline samples ABBA’s instrumental introduction from “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme!,” so the historiography is already present in the musical combination. “Time goes by, so slowly” is a continuous refrain in “Hung Up” and is used to great effect in Takemoto’s soundtrack, repeated incessantly over and over. It becomes a formal trope that also underscores collective resignation and signals the dull repetition of camp life, its rigid and impersonal regimentation, and forced labor assignments. But the lyric has a longer history, too: it is a key line in the Righteous Brothers’ Unchained Melody (1965), originally written for a prison film a decade prior, in 1955.

The collapse of song and Onuma’s lip sync is interspersed twofold: with cuts of incarceration-era footage of dining hall service and the general malaise of camp life and wartime-era beefcakes; that is, semipornographic images of male bodybuilders and models. Takemoto’s performance is the ultimate mash-up: a joyful embrace of high camp as a strategy to mitigate the oppressions of camp life, resulting in a literal eroticism of historiography.

As literary theorist Elizabeth Freeman has demonstrated, the construction of time is a bureaucratic framing that cannot possibly contain or speak to the tenuous social contracts or formations of queer time that she theorizes, what she calls “erotohistoriography,” in which queer desire can be rethought as a time-based endeavor that injects new, previously uncharted narrative possibilities into relatively static and accepted cultural histories, or, for Takemoto’s purposes, Asian American social histories. For Freeman, the locus of queer survival is predicated upon brief windows of opportunity to create an erotics of pleasurable time, and, with it, an accounting of relations and relationships—unreported, unacknowledged—that reinvent or reorient received heterosexist histories. Erotohistoriography is a means of working against the now-accepted trope of queer melancholia in its many historical and cultural guises: social rejection, loss of family of origin, loss of lovers, illness (AIDS and breast cancer—neither unique to queer communities, but strong markers of the LGBTQ experience), mourning, grief, or as literary scholar Carolyn Allen has neatly ascribed, “disappointed maturity.”5

“Disappointed maturity” is a phrase oriented toward the past: painful memories, feelings, and early personal events and histories. As Freeman points out, such an orientation sits in direct opposition to the revisionist and affirmational possibilities of futurity. Even at the risk of sounding teleological, she advocates for a kind of forward momentum, one that offers the ability to foment agency in the present moment. Performance studies scholar José Esteban Muñoz makes a similar, albeit slightly later argument, that queerness itself is spatial, temporal, achingly hopeful, and “attuned to comprehending the not-yet-here.”6 Heavily influenced by Freeman in his pioneering book, Cruising Utopia, he advocates for a turn away from what he calls “the romance of negativity.”7

Freeman asks “how might queer practices of pleasure, specifically, the bodily enjoyments that travel under the sign of queer sex, be thought of as temporal practices, even as portals to historical thinking?”8 In thinking about Takemoto’s film, these portals are a direct reference not to the sci-fi futurism of wormholes and time travel but rather to the parallel universe of the past as situated in Takemoto’s artistic practice. Most specifically, their use of filmic space as a site of locational memory, layering historical footage with narrative performance, in which the audience is acutely aware that the past is being represented, but without any expectation of realism: Takemoto breathing life into a set of circumstances through erotohistoriography, a means through which Jiro’s own sexual persona is reclaimed and—most crucially—affirmed as a robust lived experience, rather than a flat historical fact: there were indeed queer people held in confinement during Japanese American incarceration, and they had sex lives.

Trans

Takemoto’s film is not a reenactment: its soundtrack alone is set many decades into the future, a snapshot of queer club culture, which becomes an important marker of liberatory release. The gay bar or nightclub is also the proper setting for Takemoto’s own drag king performance, and therefore underscores a framework of transgressive futurisms that the film undertakes. First, “transhistoricism”: layering queer signifiers (ABBA, Madonna, musclemen) while maintaining historical specificity (Onuma at Topaz) to collapse the decades by creating a nonlinear portal that crosses the threshold of queer experience. Second, “transgendering” the body: Takemoto’s performance as Onuma is a form of gender-crossing, a nonbinary body inhabiting a gay male psyche once confined to the same—but differently divisive—set of circumstances through which their own grandparents lived. In essence, the artist destabilizes the categories of subjectivity and witnessing, underscoring the existence of memory—less as a quest for a static and unchanging past and more as a life-giving architecture of pleasurable renewal—and building up layers of possibility. And, finally, the “transitory” nature of Takemoto’s experimentalism, in that world-making is fleeting: they offer an affirmation of the transgressive nature of queer resilience through the layers of self-transformation—Takemoto-as-Onuma and Onuma’s muscled, musical fantasia.

While singing, Onuma begins kneading bread (fig. 2)—a most American, institutional food—signaling preparation, perhaps for the following day’s service. Time lapses, and Onuma retrieves the fully baked loaves with their oiled, contoured surfaces. There is, however, a surprising twist: Onuma has produced bread “muscles,” hollow loaves that he slips over each of his own thin arms, lubricated with Crisco. This act of inserting his balled fists and full arms into the bread’s opening becomes a veiled reference to the queer sexual practice of anal fisting.9

Fig. 2. Tina Takemoto, Looking for Jiro, 2011. Moving image clip, from single-channel digital video with sound, 0:28 min.

In his muscle-drag, Onuma poses evocatively and dances proudly, fully self-actualized among a chorus of other dancers. He has transformed himself into the kind of muscle man he desires and for whom he pines, surrounded by the promise of future community. Takemoto describes finding a medallion in Onuma’s personal effects that signaled his completion of Liederman’s twelve-week course. Instead of signaling mere self-improvement, Takemoto enacts a campy snapshot that is both celebratory but also deadly serious, in which the body itself is both the site and literal embodiment of emancipation.

Onuma’s sexual agency is circumscribed by a fully heteronormative camp environment, surrounded largely by family units. The legacy focus of Japanese American incarceration has been perpetually tilted toward upholding a history of heteropatriarchy: narratives of union formation, large extended families, and the binary social roles neatly ascribed to men and women—men as protectors, even under duress; women in charge of the children and the home, however makeshift.

There is an assumption of longing for whiteness or heterosexuality, but instead Onuma’s desires become a form of what Muñoz has theorized as “disidentification,” a simultaneous strategy of resistance and survival for queers of color through the transformation of mainstream heterosexuality, whiteness, and muscularity, all in service of the midcentury ideology of white masculinity.10 Nonwhite, nonmuscular, and nonheterosexual, racially and physically distinct from his own articulated (and perhaps subconscious) desires, Onuma’s experiences of difference reflect what critical race psychologists David Eng and Shinhee Han call the “social violence and psychic pain” regarding the historical conditions and experiences of Asian minorities in the United States.11

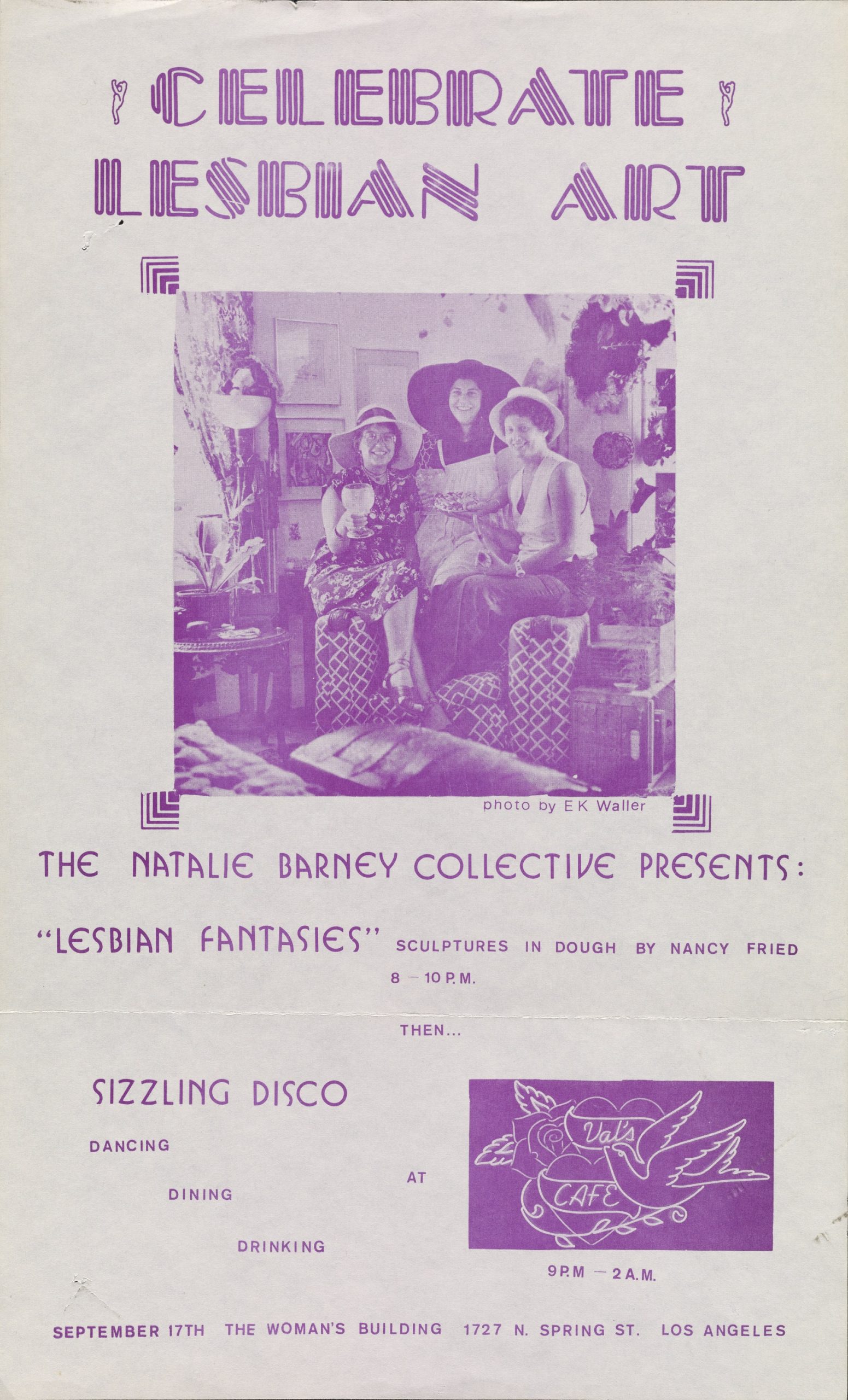

Queer futurity has always depended upon the excavation of past precedents as a means of rewriting systemic exclusion from dominant histories. In 1977, over a decade before Julien’s Looking for Langston, the pioneering feminist art historian Arlene Raven and her students at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles established the Natalie Barney Collective, a lesbian group that sought to elucidate lesbian creativity through educational initiatives, as well as to “be elegant and outrageous lesbian creators.”12 Modeled after 1920s Left Bank bohemianism (fig. 3), specifically writer Natalie Barney’s Paris salon, the group met privately at each other’s apartments. They dressed up as thrift store flappers and in masculine suits, modeling themselves on the butch-femme relationships portrayed in Barney’s famed circle, which consisted of artistic luminaries such as Djuna Barnes, Romaine Brooks, Radclyffe Hall, Mina Loy, and Una Troubridge. The Natalie Barney Collective poster featured an exhibition by sculptor Nancy Fried, a lesbian artist who, pertinent to Takemoto’s work, worked exclusively for a time with bread dough.

Unlike these avant-garde antecedents, Onuma as a gay Japanese American man more than likely did not have a queer circle to help bolster the darkness of his incarceration. Using a mixture of levity and pathos (fig. 4), Takemoto firmly asserts the likely isolation of his experience and the requisite secrecy surrounding his own desires. In keeping with the Buddhist practice of honoring the dead through shrines, Takemoto’s film can be repurposed as a form of ancestor worship, setting forth the possibility of a dynamic lineage of queer Asian American ancestry, a way of restoring faith—not in blood relations, but in the queer standby: “love makes a family.” Erotohistoriography, then, offers an access point beyond familial histories and instead is a portal to queer historical thinking, honoring the queer Asian American histories that have gone missing.13

Fig. 4. Tina Takemoto, Looking for Jiro, 2011. Moving image clip, single-channel digital video with sound, 0:27 min.

Visualizing Detainment: Bird Pins

The second part of Takemoto’s exploration of Onuma’s archive is sculptural, semi-fictive and craft-based: the remaking and queering of his personal possessions, in particular, those that signaled camp life, such as hand-carved bird pins that were frequently worn and traded as prized keepsakes. Takemoto’s bird pins (fig. 5) are remade as carved wooden bird cufflinks, a necktie clip, and a wallet and cigarette holder made of tar paper, a ubiquitous camp material used for weatherproofing within the drafty, uninsulated barracks. These objects enact a form of embellishment and are linked to gender performance.

In Takemoto’s vision, Onuma’s carved objects become “gentlemen’s accessories” and are sexually specific—pegged to the refinement of dandyism, an excessive delight in dressing up or dressing for a special occasion, a lover, or a specific kind of exhibitionism that is coded as queer. Within Onuma’s archive itself, Takemoto also recovered prewar photographs, including a commissioned portrait taken at a Japanese American portrait studio in Japantown, San Francisco, showing Onuma with friends dressed in crisp suits and wearing cufflinks.14

Takemoto’s remaking of accessories that conjure the historical archival photographs recuperate context, heritage, and the few personal keepsakes that lasted the duration of camp life’s intensive privation. Takemoto’s objects are copies but not readymades. In copying, their status as private mementos become a form of transference, another kind of threshold exploration in the psychoanalytic sense: Takemoto’s remake is a form of transferring affection or pathos for their long-dead subject, Onuma. As they speculate, “Is it possible to form personal and affective attachments to queer individuals and absent memories through the objects and materials they leave behind?”15

In practice, Onuma’s bird pins are among the most common craft objects that remain in the afterlife of Japanese American confinement. They are part of a large group of camp-based arts and crafts (fig. 6) made from a combination of natural materials and scavenged objects, including artificial flowers made of paper, wearable pins made of shell and bits of bone, wooden game boards, hand-carved signs and letterboxes made from scrap wood, embroidered table coverings, and many other inventive and functional objects created for enrichment, need, and cultural pride.16

Collectively, these historic objects are known as gaman, a Japanese term that translates to “enduring the unbearable” or “perseverance.” While culturally specific, the idea of perseverance is aligned with queer resilience. For Onuma, it became two sides of the same coin: objects of futurity, such as the bird pins, that signaled the ability to look forward to another place and time, a pathway to escape or the freedom of flight itself. Takemoto’s bird pins are trace memorials to Onuma’s sexuality, reworking the neutrality of the symbolism into something queerer and more specifically related to the dandyism of Onuma’s pre-camp life in San Francisco. The anonymity of the objects themselves—crafted in camp, under duress—elides with the lack of freedom in which Takemoto’s erotohistoriography within Looking for Jiro itself unfolds. On offer is a history of private sensation, created during less-than-advantageous conditions, persevering regardless.

In 1992, the late curator Karin M. Higa organized The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942–1945, the largest exhibition on the subject that focused on the art production (largely painting and drawing) facilitated by the camp art schools set up by Chiura Obata and George Matsuaburo Hibi. Most recently, art historian ShiPu Wang curated the first comprehensive retrospective on Obata.17 These exhibitions, however, did not include the material cultural production of these craft objects, which have largely been collected and catalogued through historical societies and museums rather than visual arts institutions. This has reinforced the so-called amateurism historically associated with craft, in which gaman is treated as an anthropological or folkloric class of objects, instead of offered the stewardship and visual analysis of art history.

Allen Eaton’s Beauty Behind Barbed Wire (1952)

In 1945, the politician-turned-craft advocate Allen H. Eaton toured five war-era Japanese American incarceration camps as a representative of the Russell Sage Foundation, a social services agency funded in part by the philanthropy of the Rockefeller family. What came of Eaton’s enthusiastic witnessing was the book Beauty Behind Barbed Wire (1952), which is the only primary source focused on the hobbyist elements of craft within the camps, documenting gaman as it was made and circulated.

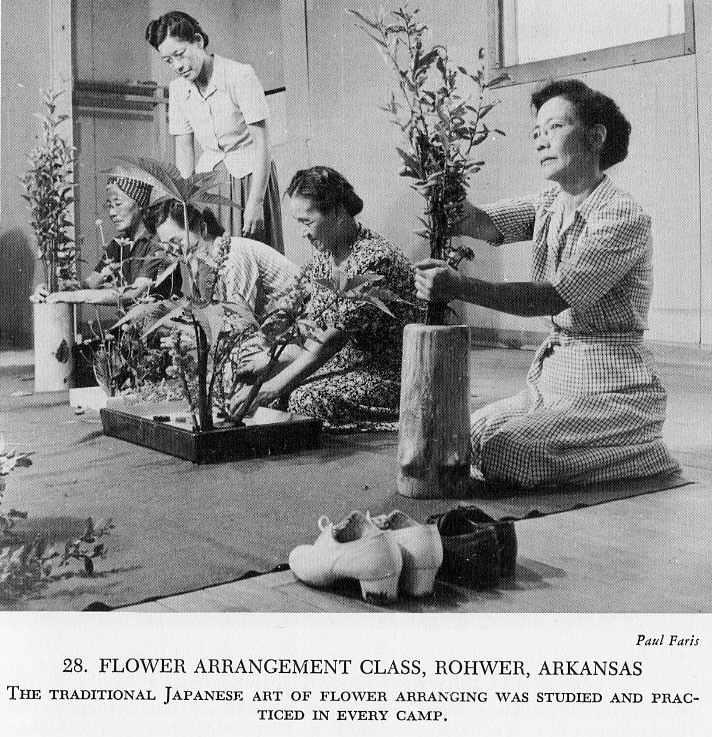

The book takes pains to emphasize the beautifying program upon which Japanese Americans embarked: planting gardens, building and carving furniture, making artificial crepe paper flowers, and teaching each other skills such as ikebana (flower arranging), calligraphy, and embroidery. Eaton conveyed the joy in handmade labor as an escape from the difficulty and monotony of camp life:

It was at these camps that most of these arts were created . . . to help them face the uncertain, disheartening, and confusing life before them . . . The Japanese are renowned for their ability to create order and beauty out of what is at hand, and that is exactly what thousands of evacuees began doing right away.18

In Eaton’s narrative, Japanese American craftspeople derived great satisfaction and pride from their reclamation and scavenging. From his hearty descriptions, it is almost easy to believe that detainees preferred artificial flowers made of scrap paper to real ones (fig. 7) or enjoyed organizing tea ceremonies amid drafty barracks. Certainly, thrift and ingenuity are commendable attributes, but throughout his text, Eaton takes this further by essentializing these as purported traits of Japan-ness, including a quasi-spiritual connection to the land:

The stone carver at the right is at work at Manzanar, California. He brought from his native Japan a knowledge of, and an interest in, the slate and stone of the western mountains that could not have come in any other way, for he saw in the ledge of rock the ancient inkstones of the East, as other Japanese did.19

In choosing to portray the desert and mountainous camp landscapes as benign, spiritual forces (when in fact they were quite the opposite) that connected Japanese Americans to their ancestral homeland, Eaton’s book fosters a fated quality to incarceration, as though their oppression held broad spiritual significance that was appropriately channeled into exceptional material production.

As a celebration of the amateur, Eaton paints a portrait of craft as a cultural legacy belonging to all detainees, rather than individual artisans. His strategy was to select the best example of a particular art form, often shaped by the environs of the camp location itself, and publish the representative photograph with an extended caption. For example, Minidoka (Idaho) was a center where gardening and the shaping of desert sagebrush prevailed, while Tule Lake (California) and Topaz (Utah) were both located near ancient lakebeds replete with shells that residents collected and used decoratively in sculptural compositions and on wooden relief panels. At Heart Mountain (Wyoming), Eaton highlighted women’s embroidery.

Unconsciously racist, Eaton’s well-meaning book becomes something else: an apologist text with a foreword by Eleanor Roosevelt. Aided by a misinterpretation of so-called Japanese spiritual values, Eaton renders handmade objects more significant than their human makers. Such false images of achievement over adversity unwittingly promoted the commodity fetishism of oppression: products were transformed by the complex interactions between a hostile government and its captive producers, resulting in the handicraft as an icon of triumph, upholding a gleaming American success narrative. Queer futurity undermines this vision, offering the possibility of private pleasures as derived from the lack of productivity itself. In such a narrative, queer people do not produce (either children or gaman), and their artistic production is tied up in the creation of the self. That is, their creative energy is spent in forming and re-forming the self, creating a persona that must simultaneously pass (as straight, meek, nonconfrontational), while harboring a shadow self, which Takemoto alludes to through their nighttime performance in Looking for Jiro.

In the immediate postwar period, Japanese Americans faced enormous discrimination during resettlement, in the form of enforced segregation through racially restrictive housing covenants that prevented them from living in whites-only neighborhoods. Compounding this was the insecurity of their civil status: it was not until 1952 that the Japanese American Citizens League successfully advocated for passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (McCarran-Walter Act), which eliminated the racial barrier to immigration and allowed the Issei (Japanese American immigrants born overseas) to gain American citizenship.20 For a white commentator such as Eaton, who observed Japanese Americans as persecuted and stateless, race became an inescapable fact of the Japanese American existence. Additionally, Japanese American art production is permanently linked to ancestry, no matter how many generations removed.

This outmoded and essentialist ideology becomes an interesting palimpsest that shadows Takemoto’s original premise: Onuma’s legacy cannot be uncoupled from incarceration, any more than the queer present can become uncoupled from its closeted past. Takemoto’s restoration of the queer experience to the collective consciousness of Japanese American detainment is an erotohistoriography that honors Onuma’s spiritedness. Moreover, it is a generative meditation on what Trinh T. Minh-ha calls “the third term,” or the phase of struggle that reinforces a form of in-betweenness: rejecting the binary in favor of linking across the transhistorical space of queer survival and the speculative construction of belonging(s).21

Cite this article: Jenni Sorkin, “Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto’s Queer Futurity,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11411.

PDF: Sorkin, Time Goes By, So Slowly

Notes

- While Topaz War Relocation Center was the official name of the camp, Japanese American activists and scholars have since reclassified Topaz as a detention center. For historical specificity, I have left it as part of the full name here. See Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps (New York: Morrow, 1976). Weglyn was the first to change “internment camps” to the implied violence and confinement of the more historically specific term “concentration camps.” Weglyn’s scholarship and activism led to the reparations movement. See also Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, “Words Can Lie or Clarify: Terminology of the World War II Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” National Park Service, 2009, accessed April 27, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/tule/learn/education/upload/words_can_lie_or_clarify.pdf. ↵

- Tina Takemoto, “Looking for Jiro Onuma: A Queer Mediation on the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during the War,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 20, no. 2 (2014): 244. ↵

- Looking for Jiro is a single-channel video with found footage. It has been shown at the following selected spaces and museums: SOMArts San Francisco (2012), Vargas Museum, The Philippines (2012), and the Oakland Museum of California (2019). The film has been screened widely in the following selected festivals: Homoscope International Queer Experimental Film, Video and Arts, Austin (2011); The Austin Gay and Lesbian International Film Festival (2012); Green Papaya Art Projects, Quezon City, Philippines (2012); Japan Foundation, Mami Art Center, Hanoi (2012); MIX Milan: Lesbian and Gay Film Festival (2012); Frameline 36: San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival (2012); CMG Short Film Festival (2012); 28th Boston LGBT Film Festival (2012); 8th Queer Women of Color Film Festival (2012); 30th Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival (2012); Hamburg International Queer Film Festival (2013); TranScreen Film Festival, Amsterdam (2013); Centre for Contemporary Arts, Digital Desperados, Glasgow (2012); Rio Gay Film Festival, Rio de Janeiro (2013); Queer Week Film Festival, Paris (2013); and numerous others. ↵

- Whitney Strub, “The Clearly Obscene and the Queerly Obscene: Heteronormativity and Obscenity in Cold War Los Angeles,” American Quarterly 60, no. 2 (June 2008): 374. ↵

- This phrase is in direct relationship to Djuna Barnes and her expatriate circle, in a particularly close reading of Djuna Barnes, The Book of Repulsive Women (New York: Bruno, 1915). While Barnes repudiated the book, I am appropriating Allen’s phrase here as a form of direct opposition to the futurity implied in Freeman’s term. See Carolyn Allen, “Djuna Barnes: Looking Like a Lesbian/Poet,” in The Modern Woman Revisited: Paris between the Wars, ed. Whitney Chadwick and Tirza True Latimer (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003), 148. ↵

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 12. In his book, Muñoz acknowledges the debt to Freeman’s formative work. ↵

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 12. ↵

- Elizabeth Freeman, “Time Binds, or Erotohistoriography,” Social Text 84–85 23, nos. 3/4 (Fall/Winter 2005), 59. ↵

- For a global response to the particularly queer subtexts and sexual practices of Looking for Jiro (2011), see Alpesh Kantilal Patel, “Artistic Responses to LGBTQI Gaps in Archives: From World War II Asian America to Postwar Soviet Estonia,” in Globalizing Eastern European Art Histories: Past and Present, ed. Beáta Hock and Anu Allas (London: Routledge, 2018), 202–15. For an activist framework, see also Tina Takemoto with Jennifer Gonzalez, “Triple Threat: Queer Feminist of Color Performance Art,” in Otherwise: Imagining Queer Feminist Art Histories, ed. Amelia Jones and Erin Silver (Manchester, UK : Manchester University Press, 2016), 294–303. ↵

- José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). ↵

- David Eng and Shinhee Han, “Introduction,” in Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation: On the Social and Psychic Lives of Asian Americans (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 8. ↵

- Terry Wolverton, “The Lesbian Art Project,” Heresies 7 (Women Working Together) 2, no. 3 (Spring 1979): 15. ↵

- Most recently, religious studies scholar Duncan Ryüken Williams has argued through the use of declassified documents that Japanese Americans were singled out for incarceration during World War II due to their majority-Buddhist faith. See Duncan Ryüken Williams, American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019). ↵

- Takemoto performs their own extended analysis of Onuma’s photographs. See Takemoto, “Looking for Jiro Onuma,” 249–54. Japanese American camera clubs along the west coast were the predecessors to the thriving small business of ethnically owned photography studios and camera shops. See Rachel Sailor, “‘You Must Become Dreamy’: Complicating Japanese-American Pictorialism and the Early Twentieth-Century Regional West,” European Journal of American Studies 9, no. 3 (2014): 1–18; and Dennis Reed, ed., Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940 (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2016). ↵

- Takemoto, “Looking for Jiro Onuma,” 243. ↵

- In 2012, critic Delphine Hirasuna, whose own Nisei (American born, second-generation) parents were detainees, organized a critically acclaimed, nationally touring show of arts and craft objects made during the period of incarceration. The impetus for doing so was her initial discovery of a single bird pin buried among her parents’ possessions. See Delphine Hirasuna, The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942–1946 (Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2005), 6–7, and Delphine Hirasuna, “The Art of Gaman,” National Parks (Fall 2011), 45. Anthropologist Jane Dusselier has also argued for the political efficacy and collective expression of loss sublimated in camp-made material production. See Jane Dusselier, Artifacts of Loss: Crafting Survival in Japanese American Concentration Camps (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008). ↵

- ShiPu Wang, ed., Chiura Obata: An American Modern, exh. cat. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018). ↵

- Allen H. Eaton, Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952), 175, 184. ↵

- Eaton, Beauty Behind Barbed Wire, 69. ↵

- See the Japanese American Citizen’s League website for a timeline of advocacy and legislation: www.jacl.org (accessed April 27, 2021). ↵

- Ute Meta Bauer in conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha, “The story never really begins nor ends,” presentation at the California College of the Arts, Wattis Institute, San Francisco, October 17, 2019, https://vimeo.com/367136621. ↵

About the Author(s): Jenni Sorkin is Associate Professor in the department of History of Art and Architecture, University of California, Santa Barbara