“American” Photographs Abroad: Traveling with Lewis Hine

PDF: Zelt, American Photographs Abroad

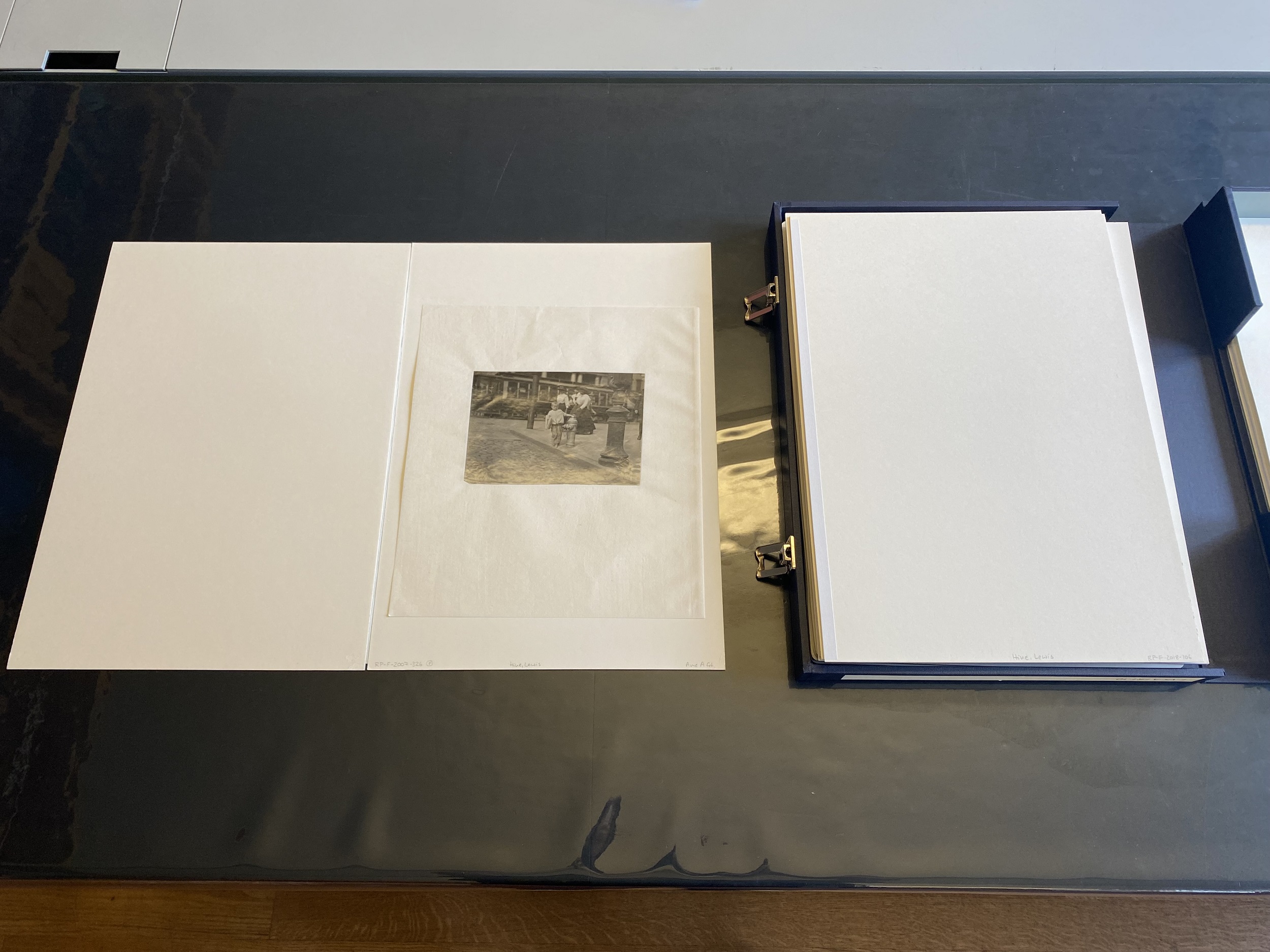

Steps away from an Amsterdam canal, a photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine (1874–1940) rests between layers of thick matboard in a secure box (fig. 1). Hine made the picture in a Richmond, Virginia, street in June 1911, partially angled toward an intersection. A small, pale boy stands in the center of the frame, leaning toward the street (fig. 2). The boy’s face is scrunched up against the raking light. One of his hands grips a fire hydrant while the other clutches a newspaper. His bare feet balance, one in front of the other, on the curb. This photograph also includes partial views of a streetcar and various passersby: a group of three Black women in hats, shirtsleeves, and dark skirts, pictured mid-stride and mid-conversation, and two white men in suits moving past. The boy is the only figure standing still in a photograph that has itself moved continents: from the Richmond summer heat to the permanent collection of Rijksmuseum, where its meaning was transformed via an error of cataloguing. This photograph has been reproduced as Newspaper Vendor, New York, 1909 throughout its life in the Dutch museum. The discovery of this commonplace cataloging error helped me contextualize Hine’s photographs of child labor in the history of photography and theorizations of race in the United States and the Netherlands, allowing me to explore how race shaped Hine’s goals and the reception of the photograph. The situation raises questions about the enduring impact of racial hierarchy in Hine’s child labor photographs, as well as the role of whiteness in the formation of “American” photography more broadly.

As an historian of art of the United States, I arrived in Amsterdam in January 2021, mid-lockdown, for a research fellowship to study what counts as “American photography” in the collections and minds of curators working in Europe and the United Kingdom. My goal was to consider the shift in perspective that occurs when a national identification and a medium are seen transnationally by tracing the ways cultural constructions, specifically race, permeate and inform versions of “American” identity housed in international art museums.1 Like Hine’s photograph, these issues involve an active intersection of people, places, objects, histories, and intentions.

Hine’s photograph arrived at the Rijksmuseum from what was then Bonni Benrubi Gallery in 2007. Two years prior, the museum’s curators of photography decided to focus on collecting “American photographs.”2 This work was the first by Hine selected for purchase by the museum.3 It was acquired with funds from the multinational law firm Baker McKenzie, which remains a steadfast supporter of the Rijksmuseum’s efforts to collect photographs of the United States.4

The Rijksmuseum was established in 1798 as a national museum. Today the museum brands itself as the “home of the Dutch masters,” aiming to offer “a representative overview of Dutch art and history from the Middle Ages onward, and major aspects of European and Asian art.”5 Yet, as evident in the 2021 exhibition Slavernij (Slavery), the museum’s first show devoted to the Dutch institution of slavery in the Republic of Suriname on the northeastern coast of South America and in the Caribbean island of Curaçao, the museum, its curators, and its collections present an expansive vision of an imperial history that includes the Americas as well. Hine’s photograph is part of this vision. The production of Slavernij was announced in February 2017 amid a groundswell of support for the Black Lives Matter movement globally and increased local attention to the enduring role of racial hierarchies, especially in relationship to the colonial past and “white innocence” in Dutch culture.

Building upon decades of scholarship on race in Dutch culture, social and cultural anthropologist Gloria Wekker evokes “white innocence” as a strong paradox at the heart of the nation. She defines this term as a “dominant way in which the Dutch think of themselves, as being a small, but just, ethical nation; color-blind, thus free of racism,” where “using the r-word . . . is like entering a minefield.”6 Wekker’s book—first published in English in 2016 and in Dutch the following year—sparked sustained and heated national debate.7 The Netherlands—Amsterdam, specifically—fostered modern economic and social liberalism, describing themselves as “diverse on every level.”8 Thus, the opening of Slavernij in 2021 made “race”—a term that is still often considered pejorative in the Netherlands—a preoccupation of the staff working across the national museum.9 Throughout the ensuing conversations about race that arose at the time, the curators of photography continued to look to the United States for ways photographs harbor evidence of national identity.

Innocence and Hine’s Child Labor Photographs

I began to research the Hine photograph, among hundreds of photographs in the collection classified as “American,” because it pictures figures of different races, genders, classes, and ages in a single frame. This is a combination that is unusual for Hine’s work for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC).10 The photographs Hine made of children for the NCLC were critical to Progressive reformers’ efforts in securing legal protections for child laborers through the enactment and enforcement of new and existing legislation placing limits on the age of workers. Hine’s photographs and the public support they aroused catalyzed the creation of the Children’s Bureau in 1912 and helped urge the US Congress to pass the 1916 Keating-Owen Act, which involved limited legislative actions meant to deter employers from exploiting child labor. Despite this agenda, Hine’s powerful photographs rarely depict subjects of different races in the same frame.

Hine began as a staff photographer for the NCLC in August 1908, and his early projects took place across the rapidly industrializing southern United States. He traveled more than fifty thousand miles over three years, shifting focus from mill and factory workers to child street laborers. Oenone Kubie notes that Hine’s transition to street laborers occurred in 1911—the same year he made the Richmond photograph. For Hine and his employers, children working on the street were at moral risk: children’s use of public space beyond the control of adult supervision left them vulnerable to corruption because of their proximity to immorality.11 One of Hine’s most circulated exhibitions on children’s labor conditions featured images of children working on the street with text stressing “moral dangers” because of the young workers’ familiarity with saloons and gambling, for example.12 By appealing to child labor’s threat to morality and childhood innocence, not just physical harm, Hine and the Progressive reformers he worked for provided a language through which to communicate the stakes of their mission.

Looking at the Rijksmuseum photograph, I note that the centrality of the white child emphasizes the juxtapositions of class, gender, and race taking place in the frame, leading me to question the presumed identity of this “child” for whom Hine advocates. Given the racialized context of the United States at the turn of the century, did Hine’s photographs uphold different meanings of childhood for white and Black children? At the time when Hine worked for the NCLC, Black children were excluded from the notions of innocence and childhood that undergirded the kinds of moral and physical risks his work sought to highlight. By the end of the nineteenth century, as historian Robin Bernstein shows, childhood innocence in the United States was raced as white and enforced by claims of racial obliviousness. White childhood innocence helped to secure the unmarked, normative status of whiteness. Bernstein contextualizes cultural projects to reveal distinct racial trajectories within representations of children, with white children constructed as tender angels and Black children “libeled as unfeeling, noninnocent nonchildren.”13 Political projects utilized such constructions of childhood to claim racial innocence and “appear innocuous, natural, and therefore justified.”14 When I saw the Rijksmuseum photograph amid the context of the discussion of “white innocence” and race in the Netherlands, it occurred to me that Hine as an image maker might have similarly used the conventions of racial hierarchy and childhood to communicate urgency in his message to his contemporary audience.

Visual Communication, Race, and the NCLC

As an artist, Hine was gifted at using context and composition to point to the unmarked mechanisms of power dynamics in everyday life. Early scholarship on Hine’s labor photographs notes his ability to grasp and use the social structures surrounding him as communicative tools. In the 1949 edition of The History of Photography, Beaumont Newhall stresses that Hine can “comprehend instantly and without effort the background and its social implications; unbothered by unnecessary details, his sympathies concentrate on the individual before him.”15 Alan Trachtenberg notes the ways Hine utilized such visual social cues to communicate with his imagined and predominantly white audience. Trachtenberg argues that Hine’s photographs and his means of distributing them trafficked in a “macro-structure of social meaning,” that “each image belonged to a larger picture and, understood that way, by way of its social identification, could thus evoke the whole for which it stood.”16 In his scholarship on Hine’s photographs of child laborers in the New South, John R. Kemp explains that Hine’s images of working children “were meant to shock and anger their viewers, to rouse the public against a system Hine abhorred.”17 Across the literature, Hine is acknowledged for his skill at making photographs that offer indisputable evidence while simultaneously utilizing social context to provoke sentiments and action from his audience.

Further, Hine would undoubtedly have been aware of the stakes and rhetoric of racial superiority and childhood while he worked in Richmond. Prior to stepping foot in the former capital of the Confederacy, Hine’s child labor photographs had already been framed in the context of the racial hierarchy of the South in a 1909 article in Charities and the Commons.18 In her introduction to the article and to Hine’s photographs of children, the secretary of the National Consumers League, Florence Kelley, a dedicated anti–child labor reformer, specifically stressed that Hine’s advocacy was to benefit white children: “The ingenuity of a young photographer [provides] for current knowledge of the sad lot of the most unfortunate of our little fellow citizens—the white, English speaking, native children of the southern cotton states.”19 Hine’s boss, Alexander J. McKelway, helped found the NCLC and served as the secretary for the Southern states. A leader in the anti–child labor movement, McKelway wrote the text that accompanied Hine’s photographs in the same publication. Hine scholars have noted that McKelway advocated for reform using the New South’s existing structures of racial superiority as justification, warning that the “very strength and vigor of our pure Anglo-Saxon stock is being sapped by this system of working the little children.”20 According to Peter Sexias, “McKelway typified Southern Progressive reformers who fought for limited and specific humanitarian changes while being careful not to upset the basic social, racial and economic arrangements which ruled Southern society.”21 These are just a couple of examples of Hine’s contemporaries exploiting notions of racial hierarchy to advocate for progressive causes that are discursively coded as white.

Interpreting New York Lives Abroad

Keeping this role of whiteness and innocence in mind, I looked at the ways Hine’s Richmond photograph has been interpreted at the Rijksmuseum. As mentioned above, until 2021, the museum had exhibited and published the photograph under the title Newspaper Vendor, New York, 1909. Every mention of the photo stressed Hine’s intent and advocacy for child labor reform, as well as his own importance as a central figure in the history of photography of the United States. Each published interpretation by the Rijksmuseum either ignored the group of women in the frame or relegated them to background context. The acquisition essay published in the museum’s public journal, the Rijksmuseum Bulletin, for example, describes the photograph as “almost like the genre of street sellers or street types we know from prints like ‘Cris de Paris.’ In Hine’s ‘Cries of New York’, however, we get the setting as well: the dark women in the background and the tram. He gives the photograph a vitality and a magnetic quality that had seldom been seen before.”22 This interpretation raises several questions: In what ways is the “magnetic quality” the author describes charged by race? Is the typology of the child laborer achieved through the juxtaposition of a stationary white child amid the group of moving, talking, well-dressed Black women behind him? Under what conditions do people transform into setting?

When I originally believed the context of the photograph to be New York, I was struck by how the women walking past the boy and the Rijksmuseum interpretation hark directly to the role of positionality and recognition that Saidiya Hartman outlines in New York–reform photographs: “The outsiders and the uplifters fail to capture it, to get it right . . . They fail to discern the beauty and they only see disorder, missing all the ways black folks create life.”23 In the museum’s interpretation, the other figures in the image are a stage for the boy’s struggle and Hine’s project, but the race of the child goes unremarked. Instead, the museum stresses Hine’s art-historical legacy, his commitment to his mission as a reformer, and the context of New York. In an effort to lift up Hine-the-uplifter as an exemplar of “American” photography, the museum perpetuated the imperception Hartman observes and eschewed the ways the photograph harbors evidence of Black life in the period and the ways the image gestures toward contemporary racial dynamics.

As I began to consider the resonances with Hartman’s argument, I found that the Rijksmuseum’s failure to discern Black life or the role of racial hierarchy in Hine’s time was not unique but, rather, pervasive in the broader treatment of Hine’s work on child labor. Each of the two texts the museum lists as references for its acquisitions essay, both of which were published in the United States, includes images of Black figures but avoids all discussion of race or the lives of Black Americans at the turn of the century. The 1977 Aperture monograph by Alan Trachtenberg with Walter and Naomi Rosenblum, titled America & Lewis Hine, presents an “America” that is primarily white. The single photograph picturing Black subjects includes a man and a woman walking together along a muddy street, the woman looking over her shoulder toward Hine. It is titled Red-light district at noon, Chicago, 1911.24 Similarly, Vicki Goldberg’s 1999 publication, Lewis Hine: Children at Work, mentions that Hine photographed children “amid fears that impoverished children would become damaged citizens” but does not address the racialized context of those fears.25 Additionally, as Joseph McCartin notes, no images of Black children appear in the article “Child Labor in America, 1908–1912: Photographs of Lewis Hine,” in the readily accessible online resource, The History Place.26 Thus, the Rijksmuseum interpretation of the photograph aligns with conventional framings of Hine’s work wherein his images and advocacy for children go unmarked as white.

Keeping in mind Hartman’s emphasis on the exclusion of the richness of Black life in New York and the Rijksmuseum’s emphasis on the New York setting for Hine’s photo, I dug through the (blessedly) digitized archive of the National Committee for Child Labor collection at the Library of Congress.27 Navigating the keywords and image searches, I found that no image named Newspaper Vendor, New York, 1909 existed. Instead, I found that the photograph was one of four images that Hine made in downtown Richmond, Virginia, in June of 1911 (fig. 3).28 In addition to naming the child—Willie—this exciting repositioning of the image in space and time strengthened my understanding of the photograph as evidence of Hine grappling with tropes of racial hierarchy and innocence in his work.

It was impossible to track down how and why Hine’s Richmond photograph was catalogued with the wrong title, location, and date in the Netherlands.29 Still, this slippage and the subsequent interpretation serves as a useful reminder of the ways canonical historical narratives can twist back and reinforce themselves. For example, during its life in the Netherlands, this Hine photograph was paired in publications with his most famous photograph of child labor, Sadie Pfeiffer, Spinner in a Cotton Mill, 1908, which the Rijksmuseum purchased in 2011.30 The didactic text for the photograph of Pfeiffer does not specify that it was made in the southern United States (South Carolina) but does state that Hine’s “photographs literally helped bring an end to child labour.”31 This pairing of a lesser-known photograph alongside what is well known about Hine’s reformist efforts again underscores his role as a laudable reformer.

Additionally, the initial mislocation of the photograph’s setting to New York in 1909 centers the photograph in a story of European immigration, as does the didactic text from the museum: “Hine portrayed the European immigrants who came to America at the beginning of the 20th century. Life was hard in a big city where hundreds of thousands of people were looking for ways to make a living. Italian women were employed in ‘sweatshops,’ sewing workshops, where they were grievously exploited. Even children, like this barefoot newspaper boy, were sent out to earn money.”32 This orientation of Hine’s work privileges a well-packaged story of the United States as “a nation of immigrants.” It relocates the artwork from the geographic periphery of the South to the hotspot of photography at the time, New York, the city that was making itself out to be the epicenter of modern Western art. The initial mislocation of New York fits a better known and marketed story of the history of the United States, wherein New York City stands for the nation. It also fits the ways Hine has been positioned in that history, most notably by the work of Trachtenberg, as a productive foil to Alfred Stieglitz’s modernist formalism.33 It is understandable, then, that this photograph was pulled into the orbit of metanarratives casting Hine as a triumphant reformer and key figure in “American” photography.

Moving this photograph back to Richmond, Virginia, in 1911, makes the racialized context of Hine—a white man with a big camera—an undeniable element of the image. For example, the streetcar in the background and the Black women walking on the sidewalk evoke the facts that Richmond was both the first city to launch an electric streetcar system in the United States and the first to legally segregate those streetcars based on race. To walk while Black rather than ride the streetcar was an organized form of protest until just a few years prior to when Hine made this picture.34 While Hine may not have been aware of the Richmond streetcar boycotts, it would certainly have been within memory for the women pictured and likely influenced the very paths they walked.

This photograph caused me to question how Hine positioned Black subjects in other photographs he made in Virginia in the summer of 1911. Photographs from different locations in Virginia, including the Old Dominion Glass Company in Alexandria, picture Black child workers, but when white children are present, the young Black laborers are cropped at the edge of the frame (fig. 4). Additionally, Hine’s usually detailed captions lack precision when accounting for the presence of Black children. For example, one of his captions reads, “I counted 7 white boys and several colored boys that seemed to be under 14 years old.”35

The experience of researching and reconnecting this photograph to Richmond while in the Netherlands raised several larger questions that carried me forward in my study of Hine and of the making of histories of photography of the United States more generally. Historians have established the role of white racial formation in the ways newly arrived European immigrants, working-class men, and men of the growing professional classes developed a sense of “American” identity during the turn of the twentieth century, not to mention white nativist fears of “race suicide.”36 With an influx of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and Asia, along with the increased wealth and mobility of African Americans, cases of poverty and low birth rates of white Americans caused major figures at the turn of the century, including Theodore Roosevelt, to take up the eugenicist concern that the “higher races” risked “race suicide.”37 Like the “great replacement theory” espoused by present-day politicians and right-wing commentators in the United States, “race suicide” was a white supremacist response drawing on racial hierarchy to provoke a broader racist response to American identity moving away from whiteness.38

Looking closely at Hine’s Richmond photograph, I considered how the context of racial hierarchy in 1911 might have been a tool Hine wielded in support of his mission to eradicate child labor. However compassionate and noble Hine’s efforts to reform systemic injustice were, we must conceive of a history that does not keep pulling toward an unmarked image of childhood in the United States as inherently white. Considering the context of past and present, we must write more nuanced art histories that account for the worthiness of Hine’s intentions and the depth of his talent, as well as the ways he benefited from and bolstered contemporary ideas of racial hierarchy.39

Ultimately, seeing this photograph in the Netherlands led me to pay closer attention to methods behind progressive movements for systemic change in the study of photography of the United States. In what ways does the whiteness of the established canon travel with objects into new contexts where whiteness is already at work in complicated ways? In what ways do “American” projects continue to manifest unmarked as white?40 As discussions about the enduring impact of racial hierarchies and systemic racism in the United States permeate discourses within cultural institutions abroad and international calls for racial justice, will the methods of approaching museums, collections, exhibitions, and art history transform as well? Or will the workings of racial hierarchies be limited to stories set within the geographic boundaries of the United States, in the study of art history and beyond?

At some point in its history, this photograph was transported in space and time. Now it returns to its point of origin, back to the intersection of roads, ideas, and histories in Richmond, Virginia. Unearthing this new and old information offers an opportunity to begin to think about how Hine, a reformer committed to systemic change, still trafficked in a visual language of racial hierarchy to communicate the stakes of his message and to begin to unpack the ways that the formative impact of race gets tangled even further when “American” photographs travel abroad.

Cite this article: Natalie Zelt, “’American’ Photographs Abroad: Traveling with Lewis Hine,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15068.

Notes

Thanks are due to the editors for their careful and insightful comments and for the critical help and guidance of Naoko Adachi, Stephanie Archangel, Laura Bieger, Mattie Boom, Jackson Brown, Maria Beatriz Carrión, Rebecca Giordano, Trineke Kamerling, Suzie Hermán, Namrata Kanchan, Rob Kroes, Jana LaBrasca, Tracy Liu, Damiet Scheeneisz, Janna Schoenberger, Rachel Smith, Barbara Tedder, Hans Rooseboom, Merel van Tilburg, and the small army of people in the United States and the Netherlands who helped care for my child amid COVID closures. Research for this article was supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

- The term “American” is rooted in notions of imperialism that are invested in policing which stories and whose stories belong to the designation. The use of the term “American” in the context of the Netherlands rather than “of the United States” is common, perhaps for reasons of linguistic ease; “Amerika” is more efficient to pronounce than “Verenigde Staten.” Still, the use of “Amerika” or “amerikaan” to address people and cultural products from the United States is widespread in Dutch parlance and often results in misunderstandings resonant with the term’s imperial legacy. Rob Kroes to the author, May 17, 2022. ↵

- “Terra Foundation Fellowship,” Rijksmuseum, accessed August 11, 2021, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/education/university-education/fellowship/terra-foundation-fellowship; Mattie Boom, Steven F. Joseph, and Hans Rooseboom, “Acquisitions: Photography,” Rijksmuseum Bulletin 57, no. 2 (2009): 180. The photography collection at the Rijksmuseum is structured as an Rautonomous department, called Rijksprentenkabinet (State Print Room), in the Collections sector of the museum. Other autonomous departments in the Collections sector that have curators include Geschiedenis (History) and Beeldende Kunst (Visual Arts). See Rijksmuseum 2020 Jaar Verslag (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2020), 228. The Rijksprentenkabinet at the Rijksmuseum acquires objects with relative speed and autonomy compared with collecting departments in museums in the United States, which often must seek approval and funding from various selections and acquisitions committees prior to accessioning an object. The photography curators at the Rijksmuseum operate with a budget that they may spend nimbly and freely based on their own discretionary intentions. See Brad Feuerhelm, “Hans Rooseboom,” The Nearest Truth, episode 150, January 29, 2021, https://nearesttruth.com/episodes/ep-150-rijksmuseum-curator-of-photography-hans-rooseboom, esp. 25:31–32:28. Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom are the curators of the Rijksprentenkabinet and have worked together since the collection’s founding in 1994. ↵

- Three photographs attributed to Hine had been part of the collection since the Rijksprentenkabinet’s founding in 1994. They were transferred to the museum with collections from across the Netherlands that formed the foundation for the Rijksprentenkabinet. RP-F-2007-326 is the first Hine photograph purchased outright. See entries for RP-F-F17651, RP-F-F17784, and RP-F-F03804 in Rijksstudio, accessed June 10, 2022, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio; Peter Scatborn and Ronald de Leeus, “Voorwoord/Preface,” in Een Nieuwe Kunst Fotografie in de 19de Eeuw: De Nationale Fotocollectie in het Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam / A New Art Photography in the 19th Century: The Photocollection of the Rijksmuseum, ed. Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1996), 7–9. ↵

- “Baker McKenzie Extends Partnership with Rijksmuseum by Five Years,” Rijksmuseum Press Release, June 14, 2021, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/press/press-releases/baker-mckenzie-extends-partnership-with-rijksmuseum-by-five-years. A note on curatorial agency and institutional identity: this paragraph refers to the actions of both curators and museums as independent agents. As mentioned in the notes above, the curators of photography at the Rijksmuseum pursue projects and acquire objects with relative autonomy compared to curators working in museums structured around various layers of committee and board approval. In the case of RP-F-2007-326 and across the museum more generally, in terms of public authorship, the curators’ actions become the museum’s. For example, specific authors are not listed for the acquisition essay in Boom, Joseph, and Roseboom, “Acquisitions,” nor is authorship attributed to the didactic texts that accompany the online catalogue on Rijksstudio. The actions of the curators and the institution are tangled in ways that are beyond the scope of this article to articulate. What is significant for my observations is that the actions and interpretation of individuals working internally assume the outward authority of the museum. As Erina Duganne states, museums have and continue to play a “critical role” for photography “in defining and controlling photography’s meaning and value . . . how and what they collect, organize, and display form the basis of particular narratives and interests, which become, as art historian Salah Hassan notes in his introduction to the Third African Photography Festival in Bamako, Mali, ‘the very basis for the history of art.’” See “Museums,” in Global Photography: A Critical History, ed. Erina Duganne, Heather Diack, and Terri Weissman (London: Routledge, 2020), 209. ↵

- “Vision and Mission,” Rijksmuseum, accessed August 11, 2021, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/about-us/what-we-do/vision-and-mission; see also “History,” Rijksmuseum, accessed May 10, 2022, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/about-us/what-we-do/history.“Home of the Dutch masters” is the tagline for the Rijskmuseum that appears on Google search results as of October 18, 2022. ↵

- Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016): 2, 18. See also Alison Blakely, Blacks in the Dutch World (Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 1993); Philomena Essed and Sandra Trienekens, “‘Who Wants to Feel White?’ Race, Dutch Culture and Contested Identities,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31, no.1 (2008): 52–72; Philomena Essed and Isabel Hoving, “Innocence, Smug Ignorance, Resentment: An Introduction to Dutch Racism,” Thamyris/ Intersecting 27 (2014): 9–30. ↵

- Commentary and editorials appeared for months in the national newspapers Trouw and De Telegraaf and were especially prevalent in De Volksrant, particularly after a cover story of the Vrij Nederland included an interview with Gloria Wekker outlining “white innocence” in Dutch society. See Ger Groot, “Nederland is veel diverser dan Gloria Wekker denkt,” Trouw, October 21, 2016; Rob Hoogland, “Wandeling,” De Telegraaf, October 20, 2016; Elma Drayer, “Witte superioriteit,” de Volkskrant, June 10, 2016,; Greta Riemersma, “Emeritus hoogleraar Gloria Wekker: ‘Witte onschuld bestaat niet,’” Vrij Nederland, June 6, 2022, https://www.vn.nl/gloria-wekker-witte-onschuld-bestaat-niet. ↵

- “Diversity in Amsterdam,” I Am Amsterdam, accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.iamsterdam.com/en/living/about-amsterdam/people-culture/diversity; see also Russell Shorto, Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City (New York: Doubleday, 2013). ↵

- The cultural construction of race alone is not necessarily pejorative; rather it is the hierarchies of value attached to racialized bodies and practices and the fact that race was constructed to reinforce that hierarchy that is derogatory. For more in the context of the United States, see Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2015). ↵

- See Verna Curtis and Stanley Mallach, Photography and Reform: Lewis Hine and the National Child Labor Committee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1984); Vicki Goldberg, Lewis H. Hine: Children at Work (Munich: Prestel, 1999); John R. Kemp, Lewis Hine: Photographs of Child Labor in the New South (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1986); Oenone Kubie, “Reading Lewis Hine’s Photography of Child Street Labor, 1906–1918,” Journal of American Studies 50, no. 4 (2016): 873–97. ↵

- Kubie, “Reading Lewis Hine’s Photography of Child Street Labor,” 881–82. ↵

- Kubie, “Reading Lewis Hine’s Photography of Child Street Labor,” 874–76. See the “exhibit panel” at the Library of Congress, LOT 7483, v. 2, no. 3753 {P&P} LC-H5- 3753, https://www.loc.gov/resource/nclc.04934. ↵

- Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: New York University Press, 2011), 8. ↵

- Bernstein, Racial Innocence, 33. ↵

- Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography (New York: MoMA, 1949), 171. ↵

- Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986), 200. ↵

- Kemp, Lewis Hine, 12. ↵

- Alexander J. McKelway, “Child Labor in the Carolinas,” Charities and the Commons 21 (January 1909): 743–57. ↵

- Florence Kelley,” Introductory Remarks,” Charities and the Commons 21 (January 1909): 742. ↵

- Alexander J. McKelway quoted in Kemp, Lewis Hine, 9. ↵

- Peter Sexias, “Lewis Hine: From ‘Social’ to ‘Interpretive’ Photographer,” American Quarterly 39, no. 3 (1987): 393. ↵

- Boom, Joseph, and Rooseboom, “Acquisitions,” 181. ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), Kindle, location 150. ↵

- Alan Trachtenberg, America & Lewis Hine: Photographs, 1904–1940 (New York: Aperture, 1977), 49. ↵

- Goldberg, Lewis H. Hine, 15. ↵

- Joseph McCartin, “Review Child Labor in America, 1908–1912: Photographs of Lewis W. Hine,” Journal of American History 101, no. 4 (2015): 1360–61; “Child Labor in America, 1908–1912: Photographs of Lewis W. Hine,” The History Place, accessed May 18, 2022, https://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/childlabor. ↵

- “National Child Labor Committee Collection,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc. ↵

- Members of the Richmond Railroad Museum community believe Hine’s photograph may have been made on the north side of Broad Street, in the vicinity of Richmond’s burgeoning Black commercial district of Jackson Ward. Charles McIntyre to the author, September 16, 2021. I have not been able to verify this location yet. Black figures are present in the four frames from the Library of Congress collection: this group of middle-class women, a store proprietor, and manual laborers. ↵

- Bonni Benrubi Gallery sold the Hine photograph to the Rijksmuseum in 2007 with the title “Willie, Richmond, Virginia, 1911.” According to what is accessible in present-day records of the Benrubi Gallery, the Hine photograph likely belonged to a private collector and was sold by the gallery. Further detail seems to be buried in the transition from analog to digital record keeping. Rachel Smith to the author, April 26, 2022, May 20, 2022, and June 14, 2022. While the details of acquisition and provenance of museum collection objects is commonly considered public information in the United States, the 2021 Rijksmuseum “Agreement for Services—Fellowship Agreement” requires “the strictest confidentiality” in a way that limits the citation of internal museum archives, databases, and operations. ↵

- Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom, Modern Times: Photography in the 20th Century (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2014), plates 211 and 212. ↵

- “Sadie Pfeiffer, Spinner in a Cotton Mill, Lewis Wickes Hine, 1908,” Rijksstudio, accessed May 24, 2022, http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.507077. ↵

- “Newspaper Vendor, Lewis Wickes Hine, 1909,” Rijksstudio, screenshot April 7, 2021. ↵

- Alan Trachtenberg, “Camera Work/Social Work,” in Reading American Photographs, 164–231. ↵

- Blair Murphy Kelley, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy V. Ferguson (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010): 139, 141; August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, “The Boycott Movement Against Jim Crow: Streetcars in the South, 1900–1906,” Journal of American History 55, no. 4 (1969): 756–75. ↵

- Hine’s caption for National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress, LOT 7478, no. 2265 {P&P}, accessed May 26, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018676575. ↵

- For more on constructions of whiteness and the formation of US national identity during this period, see Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998); Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 1995); David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991); Gail Bederman, Manliness & Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995); Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992). ↵

- Thomas D. Dyer, Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana University Press, 1992),143. ↵

- David Smith, “‘Replacement theory’ still Republican orthodoxy despite Buffalo shooting,” Guardian, May 22, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/may/22/great-replacement-theory-republicans; Nicholas Conessore and Karen Yourish, “A Fringe Conspiracy Theory, Fostered Online, Is Refashioned by the G.O.P.,” New York Times, May 15, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/15/us/replacement-theory-shooting-tucker-carlson.html. ↵

- Examples of scholarship on Hine in this direction are Leslie Ureña, “Portraying Race beyond Ellis Island: The Case of Lewis Hine,” International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity 8, no.1 (2020): 13–37; Jennifer Way, “Healing WW1 Soldiers with Craft Therapy and Its Photographic Narratives of Masculine Ableism and White Privilege,” Material Culture, The Journal of the International Society for Landscape, Place, & Material Culture 53, no. 2 (2021): 34–54. ↵

- For more, see Martin A. Berger, Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005); Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis, Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self (New York: International Center for Photography, 2003); Morrison, Playing in the Dark. ↵

About the Author(s): Natalie Zelt was the 2021 Terra Foundation for American Art Photography Fellow Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.