Traversing Two Cultures: A Portrait of William McIntosh, Southern Slave Owner and Lower Creek Chief

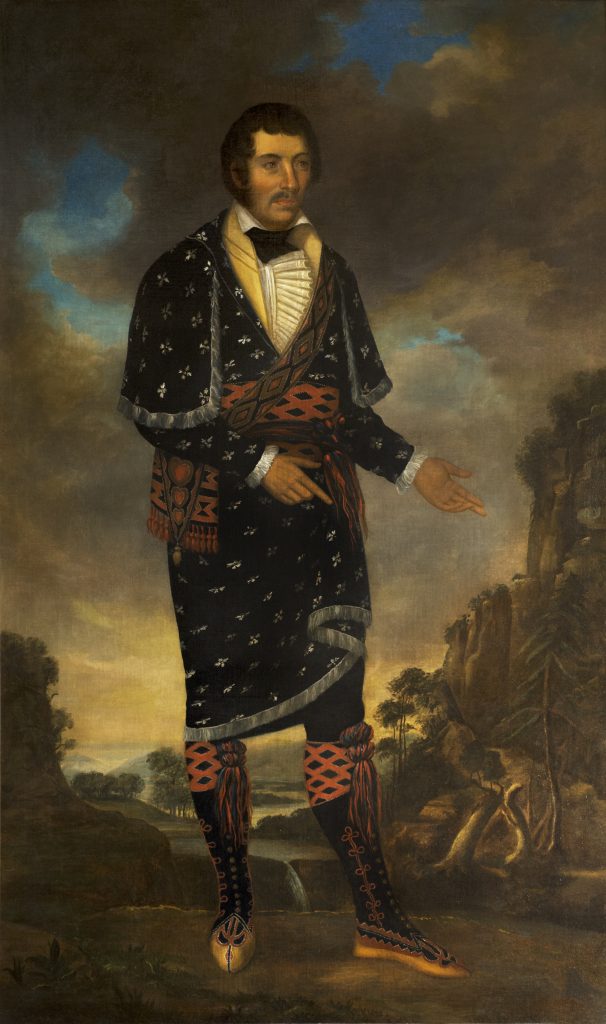

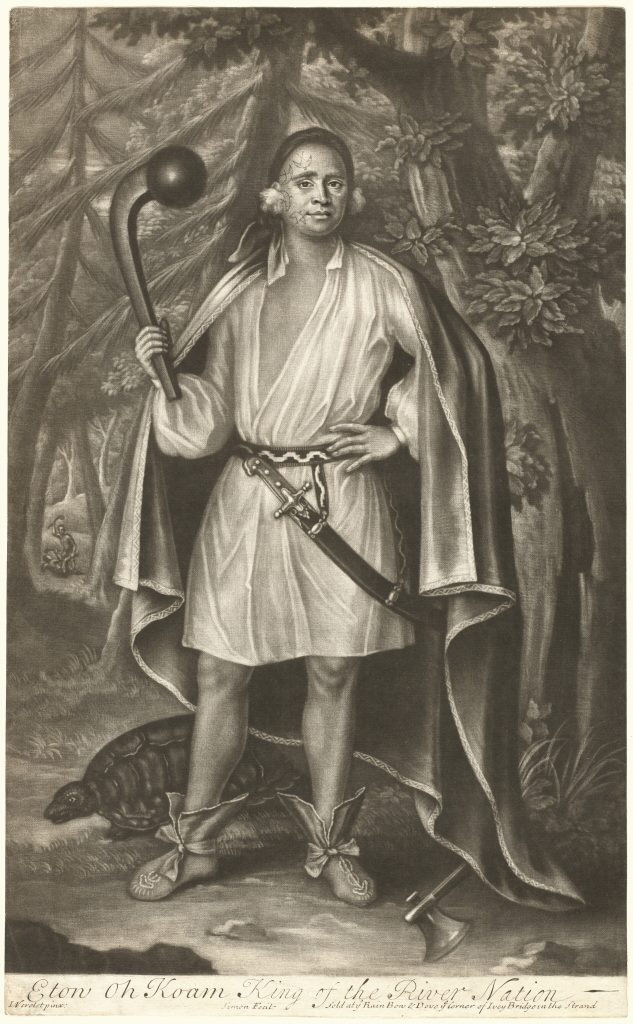

An unusual painting hangs in the densely packed, low-lit galleries of the Alabama Voices exhibition at the Alabama Department of Archives and History in Montgomery. Beyond a dugout canoe, diorama village, and video on Mvskoke-Creek life is the nine-foot-tall portrait of William McIntosh/Tustunnuggee Hutkee (fig. 1) depicting a man in Mvskoke-Creek regalia and American-style dress. The painting is flanked by trade goods—glass beads, bottles, and pipes—and reproductions of Creek portraits by John Faber Jr., Philip Georg Friedrich von Reck, Henry Inman, and Lukas Vischer. Creek activist Josiah Francis/Hillis Hadjo’s 1815 self-portrait (fig. 2)—a reproduction of which also hangs nearby—subtly counters the many portraits of Creek individuals by Euro/American artists for Euro/American audiences. The selection of artworks and objects in the gallery raise questions about Native self-fashioning, representation, portraiture, and sitter agency.

On visits to the museum, I have been drawn to the 1821 portrait of McIntosh. As a private commission, the work is neither exclusively a portrait of a Creek sitter for a non-Native audience or a self-portrait, although McIntosh used it as a vehicle of self-fashioning. In this way, it seems to reflect the complex experiences of an Indigenous individual living in early nineteenth-century Alabama and painted just two years after statehood. While the portrait appears in biographies of the sitter and Creek histories as an illustration, I was surprised to find little scholarly mention of the work.1 Intrigued, I set out to learn more.

In this brief object study, I consider how this portrait positions McIntosh as traversing between and acting as an agent for two increasingly hostile factions, the Creek Confederacy and the US government. McIntosh’s portrait operates as an important pictorial indicator of the complexities of biracial identity in the early nineteenth-century southern territories and the lengths to which one individual went in order to successfully straddle both cultures. I also became interested in how its meaning shifted as it changed ownership, signaling familial legacies, racist stereotypes, or romanticized Southern history. How could one portrait—and the individual depicted—be so flexible and subject to such varied and seemingly contradictory meanings? McIntosh and his portrait were variously coopted over their two-hundred-year history. Ultimately, this research note reflects on the ways in which portraits function as complex indicators of racial, cultural, and regional identities and histories. It argues that the flexibility of meaning for such paintings lies not only with the artist and the sitter, but is equally shaped by audiences and historians.

William McIntosh (c. 1778–1825), whose Creek name was Tustunnuggee Hutkee (White Warrior), was the son of Captain William McIntosh, a Scottish trader and British soldier with powerful familial connections within the Southeast, and Senoya, a Creek mother and member of the Wind Clan. As the child of a Creek mother and white father, he was uniquely positioned within the social and cultural hierarchies of white, Southern society and Native culture. In 1818, the Niles Weekly Register—a Baltimore-based magazine—praised his ability to be “easy and unconstrained” in “the bosom of the forest, surrounded by a band of wild and ungovernable savages” and in “the drawing room in the civilized walks of life.”2 McIntosh cannily navigated both realms, traversing settler land and Creek territories at the southeastern frontiers of Alabama and western Georgia.

On the one hand, McIntosh became a prominent Lower Creek chief and negotiated treaties with the US government. On the other, he was a Southern plantation owner, who fought and negotiated treaties for the government. McIntosh became a brigadier general in the US Army; owned two plantations, Acorn Town and Indian Springs; operated two ferries, two taverns, an inn, and an 118-mile toll road; grew cotton; and enslaved more than one hundred people.3 His father’s lineage connected him to a Georgia governor, state legislator, and Treasury Department collector. He strategically married three women: Sussanah (Creek), Peggy (Cherokee), and Eliza (Creek-American); sent his children to American schools; and married them to prominent Creek, Cherokee, and American individuals. As intermarriage increasingly became a popular US political solution for Native assimilation, Ebenezer H. Cummins identified McIntosh as an ideal example, writing: “amalgamation will have preserved precious streams of Indian blood, coursing the veins of many generous loyal citizens.”4 Such ties strengthened McIntosh’s position within Creek, Cherokee, and Southern societies, making him a natural go-between.

McIntosh was involved in state and US negotiations with the Creek National Council. Following the 1805 Louisiana Purchase, President Thomas Jefferson invited Lower Creek chiefs, including McIntosh, to Washington, DC. With deerskin trading declining, they signed the First Treaty of Washington, ceding territory in Georgia and allowing for a four-foot-wide postal path across their land.5 Without Creek approval, McIntosh assisted in widening it to a Federal Road in 1811.6 The War of 1812 increased hostilities, and in August 1813, seven hundred Red Sticks—radical, anti-American Creeks—attacked Fort Mims, killing two hundred and fifty Americans. The US response culminated in the March 27, 1814, massacre of almost one thousand Creek people at Horseshoe Bend. McIntosh commanded a Lower Creek faction that fought with the United States at Horseshoe Bend and in the First Seminole War of 1818.

McIntosh’s military exploits made him a popular US treaty envoy. In 1821, he and a group of Lower Creek chiefs negotiated the First Treaty of Indian Springs, ceding land between the Ocmulgee and Flint Rivers to Georgian farmers. McIntosh received $10,000 and one thousand acres around Indian Springs, Georgia.7 Tensions between state interests, federal policy, and Creek sovereignty came to a head with the Second Treaty of Indian Springs. In February 1825, eight of fifty-six Creek towns ceded all Lower Creek land—three million acres in Georgia and Alabama—for $400,000 and an equal tract of land west of the Mississippi River, promising to emigrate there by September 1826. The signatories received half the money, while McIntosh—the only Creek National Council member—retained his land. By negotiating without Council approval, he broke Creek law. Adding insult to injury, Georgia Governor George McIntosh Troup (1823–27) began surveying the land early and relied on his cousin to facilitate. The Creek Confederacy acted quickly. On April 30, 1825, four hundred Law Menders—Creek warriors who dispensed tribal justice—set fire to McIntosh’s house and executed him.8 They also lodged a complaint with the United States government, who voided and renegotiated the Treaty. This rankled state government and settlers, exacerbating Creek-US tensions. These events contributed to the cultural suppression and forced relocation of Creeks to Indian Territory. Between the first voluntary migration of McIntosh supporters (and enslaved persons) in 1827, and the end of official removal policies in 1837, more than twenty-three thousand Creeks moved to present-day Oklahoma.9 Today, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians reside on the only officially recognized Creek land in the state of Alabama, asserting their sovereignty on the land of their ancestors.10

Portrait of William McIntosh, Chief of the Lower Creek Indians in Georgia, is attributed to itinerant portrait painter Nathan Negus (1801–1825) and his brother Joseph. They were born in Petersham, Massachusetts; at fourteen, Nathan went to Boston to study painting.11 In 1819, Nathan traveled through the southeastern United States, where like many itinerant artists he advertised as an instructor and a painter of signs, miniatures, theatrical scenery, and portraits.12 Joseph met him in Savannah, Georgia, in March 1821, and they traveled to Eatonton, Macon, and Monticello.13 On April 23, 1821, Nathan wrote:

We started for the Indian Springs for the purpose of painting Gen’l McIntosh’s portrait. . . . The next day we travelled through the wilderness—at sundown we arrived at the place of destination—Gen’l McIntosh was too full of business to attend to his portrait and of consequence we waited several days without doing anything—here we saw about 12 hundred Indians.14

Negus’s account clarifies the relationship between sitter and portraitist: this was a prearranged commission; Negus held McIntosh in high esteem, referring to him formally; the “wilderness” and Native Americans impressed them; and before painting, they spent days observing McIntosh. The portrait likely benefited from this intimacy and understanding of McIntosh’s business and cultural identity. After completing the portrait, the brothers continued along the Old Federal Road to Cahaba, the first Alabama capital, where Joseph died in 1823; Nathan moved to Mobile, then Massachusetts, and died in 1825.15

A private commission, the nine-foot tall painting of forty-two-year-old General William McIntosh celebrates his biracial identity and simultaneously hints at the challenges he may have faced as white and Creek in the 1820s. McIntosh wears a fancy, ruffled white shirt, elaborate match coat, woven sash, and moccasins. Standing in the center of the composition, he faces slightly to our right, gesturing in that direction with both hands and indicating an ambiguous relationship to the woodlands beyond. While his left foot points right, the other is oriented toward the viewer. This indicates a man of two worlds or, at least, torn in two directions; he is simultaneously with the viewer and heading somewhere else.

McIntosh stands in front of what appears to be a traditional Romantic landscape, with rocky bluffs, blasted trees, and a mountainous backdrop in atmospheric perspective. Between McIntosh’s feet, a meandering waterway terminates in a placid pool and rushing waterfall. While seemingly idealized, this is likely Indian Springs. McIntosh received the land from treaty negotiations five months before this was painted. This detail advertises the sitter’s position via a specific property. Located between Atlanta and Macon, Georgia, the sulfurous natural spring was considered curative. In 1823, McIntosh capitalized on “the Saratoga of the South,” building an elaborate hotel and tavern.16 Furthermore, McIntosh gestures with both hands downward to his left, pointing with his index finger to two twisted trees. It is possible these were intentionally bent into marker trees or trail trees. Utilized by Southeastern Woodlands tribes, this navigation system marked trails and important natural features. McIntosh’s gesture denotes a distinctive signpost shaped, perhaps, by Creek ancestors. His expression, however, is impassive. Is he inviting us to the springs as tavern guests or tribal members? Does he demonstrate his ancestral claim on Native territory or US sanctioned land ownership? As his biography demonstrates, McIntosh’s invitation is likely open-ended.

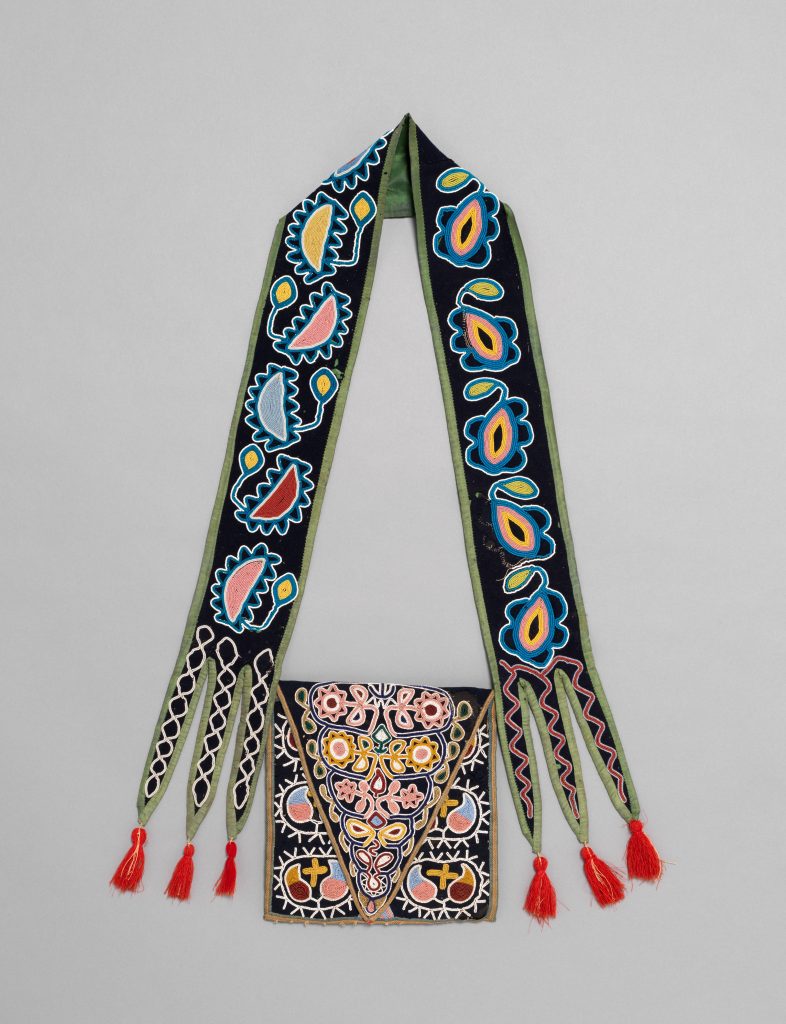

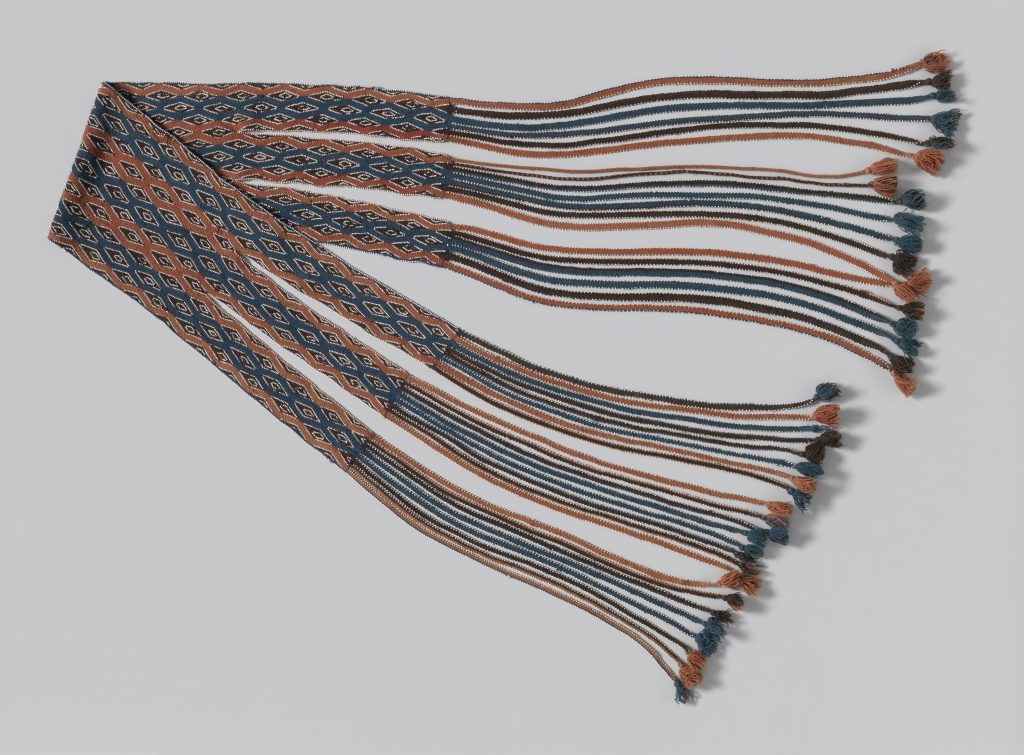

McIntosh’s style of dress signals his transcultural position.17 He wears a yellow waistcoat and white linen shirt with a high collar and a black cravat tucked behind the pleated shirt front. He dons an elaborate woolen matchcoat with fringe and a patterned, finger-woven wool sash. A hand-plaited, beaded bandolier bag hangs cross-body over his torso. Ornate leggings with ties and moccasins finish the look.18 Negus’s decorative training is evident in the flat, patterned style. The black, red, gold, and blue nested diamonds on McIntosh’s sash repeat in his ties and bandolier bag. Negus outlines the shapes with white dots indicating glass or shell beadwork.19

Comparable examples provide insight into the details and materiality of these elements. A Mvskoke-Creek bandolier bag (fig. 3) has a geometric and floral band on a black wool ground, deep triangular flap, decorative beadwork, and red tasseling, and an 1830 embroidered and beaded center-seam deerskin Mvskoke moccasin (fig. 4) displays floral and geometric designs, including a zigzag pattern around the heel. A Lower Mvskoke beaded sash (fig. 5), from about 1810, includes a similar nested diamond pattern picked out with white beading; its provenance indicates it was made for McIntosh by a daughter. Such pieces were worked by women and carried important tribal symbolism. As scholar W. Richard West Jr. (Southern Cheyenne) describes:

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—an era of immense pressure, indeed cultural emasculation that pushed Native communities to abandon tradition, including its arts forms, and assimilate into Euro-American culture—the art of beadwork was a compelling instrument of preservation for cultural traditions and Native identity.20

McIntosh’s attire—which may blend Mvskoke-Creek and Cherokee motifs (he wed Creek and Cherokee women)—acts as a significant visual operator in the conveyance of cultural knowledge during a period when Native culture was increasingly under attack. McIntosh, however, seamlessly interweaves his regalia with contemporary American fashion, signaling his biracial identity and asserting his simultaneous social position as a Southern gentleman.

McIntosh’s contemporaries commented on his dress, careful self-presentation, and racial admixture. United States Superintendent for Indian Affairs Thomas McKenney called McIntosh “the handsome Creek who looked like a swarthy-skinned Scots Highland chief,” while William Gilmore Sims said “the general expression of his countenance, its color, etc. appears to me, less to resemble the Indian, than some of the bright mulattoes whom we hourly encounter in our streets.”21 This mutability was complicated by his manner of dress, which was “a blend of European and Indian styles” and refused to conform to either.22 The portrait masterfully represents McIntosh’s cultural position, as perceived by his peers. His ambivalent pose, the duality of the landscape as Romantic and specific, and his hybrid dress indicate an individual who intentionally and self-consciously traversed Native and American cultures.

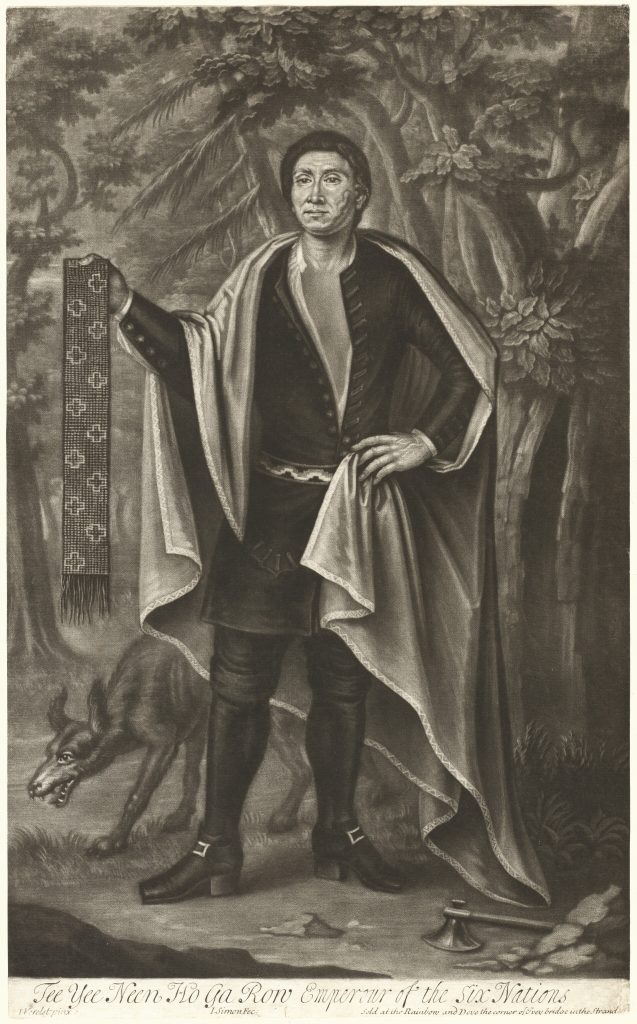

McIntosh’s Native and European-style dress is not unique in portraiture. Approximately a century prior, Dutch artist Jan Verelst (1648–1734), painted four Mohawk chiefs visiting the court of Queen Anne.23 Tee Yee Ho Ga Row of the Wolf Clan wears a black suit and silver buckled shoes and holds a wampum belt—a powerful cultural symbol. His peers wear simple white tunics and moccasins. Unlike McIntosh’s portrait, these portraits and subsequent prints (fig. 6) circulated widely, operating as conveyors of Native identity to a non-Native audience. Such images stimulated the taste for Native American goods, as epitomized by Portrait of Lieutenant John Caldwell (c. 1785; Museum of Liverpool), the British army officer who served in North America, who dons a colorful assemblage of eclectic attire. As a white, British peer, Caldwell could safely adopt Native clothing as an expressive act exactly because his racial and social positions were unquestioned.24 In contrast, Tee Yee Ho Ga Row and William McIntosh utilized dress and the established modes of portraiture to assert their hybrid positions within what historian Richard White dubs “the Middle Ground.”25 Recently, Kristine K. Ronan has developed this concept further, arguing that “an art history of the Middle Ground fluidly moves between multiple possibilities and positionalities.”26

McIntosh also appears in the Indian Gallery, around one hundred fifty portraits of Native American dignitaries mostly created by Charles Bird King (1785–1862). When Thomas McKenney published his three-volume History of the Indian Tribes of North America, he hired Henry Inman to make copies for color lithographs. Elizabeth Hutchinson writes that in reading such images, scholars should identify “the sitters’ strategies of self-fashioning within the context of long-standing cultural exchange in the region.”27 In other words, McIntosh’s portrait (fig. 7) represents him as part agent in the production of a pictorial fantasy. He is shown as a product of two cultures via a turban with egret feathers, beaded sash, checked waistcoat, and sword. While McIntosh may have self-fashioned as American and Creek for this portrait, the Indian Gallery and its publication defined McIntosh by his Indianness for an elite, largely white, American audience.28

In contrast, the Negus portrait presents a highly personal statement intended for a private audience of family, friends, and guests. The portrait celebrates McIntosh’s unique position as a cultural broker, defined by Margaret Connell Szasz as a cultural intermediary. Such individuals actively traverse the liminal zones where cultures meet. As Nancy Hagedorn describes of Andrew Montour, who negotiated Oneida and colonial spaces as a cultural broker in the 1750s:

Montour also mediated complex cultural contacts and exchanges in other, less well documented settings, as interpreter, Indian officer, husband, father, and friend. His knowledge of European and Indian cultures and his skill in translating not only languages but also culturally prescribed world views, ideas, and expectations, made him invaluable during the daily contacts between Europeans and Indians.29

This description could just as easily fit McIntosh, whose self-fashioning maximized the benefits of his biracial identity—via familial, military, governmental, tribal, and business connections—and parlayed them into position.

In researching this portrait, I was struck by the ways in which McIntosh’s legacy is as complicated as his self-fashioning. McIntosh is alternately regarded as a self-interested traitor, greedy American, or skilled opportunist leveraging Creek or US interests. After death, McIntosh was coopted by Southern historians who isolated certain aspects of his biography to reframe him within pro-slavery mythologies or as a martyr to American territorial expansion and early state sovereignty. For example, in 1854, George White outlined how McIntosh “had acquired all the manners, and much of the polish, of a Gentleman.”30 By 1896, Albert Pickett described how McIntosh was “killed for his friendship to the Georgians”; in 1917, he was called “a martyr to his friendship for the whites.”31 Thomas McAdory Owen said in 1921 that he was “a tall, finely formed man, with polished manners . . . the owner of a number of negro slaves, whom he treated kindly,” and in 1982, McIntosh “[was] slain for advocating peace with American settlers.”32 In each, McIntosh represented a mythic figure who supported the Southern, predominantly white viewpoint of the moment: alternately a gentleman, a friend to Georgia, a martyr with polished manners, a kind slave owner, and a peacemaker.

The portrait proved as malleable as McIntosh’s reputation; as it changed hands, its significance shifted. After completion in Indian Springs, Georgia, McIntosh displayed it at Coweta, a major trading town on the Old Federal Road in Alabama. McIntosh was instrumental in orchestrating the road through Coweta, where he was chief. Seen by settlers, post riders, and visitors heading throughout the Southeast, the portrait operated as a stand-in for McIntosh—who often traveled. After his death, it passed to his eldest son Chilly, who sold it in 1832 to James Kivlin, owner of the Sans Souci Tavern in Columbus, Georgia, where it hung behind the cigar counter “near the front window on a side wall . . . in full view of passersby on the sidewalk.”33 McIntosh was typecast as “the Big Indian,” as the portrait conjured popular full-length wooden sculptures of Native Americans used as tobacco shop advertising. Such racist objects evoked Native American stereotypes and facilitated the conflation of smoking with ceremonial activities. In 1922, Kivlin’s grandson sold the painting to the Alabama Department of Archives and History. It was installed near the House of Representatives Speaker’s chair at the Alabama State Capitol Building in Montgomery and took on a markedly different meaning, representing Southern martyrdom. Finally, it moved to the new archives building in 1943. Throughout, the portrait evoked familial legacies, signaled Indigenous stereotypes, heralded a romanticized regional history, authenticated the governing authority of the majority white Alabama legislature, and served as a record of a significant Southern historical figure.

The painting’s links to Southern history and heritage were doubled when ethnologist David Bushnell attributed it to “old artist Washington Allston,” a “native of South Carolina” in 1924; this was “confirmed by the Boston Academy of Fine Arts and also the Metropolitan Museum of New York City.”34 Archive records indicate Allston’s Southern identity was significant to Marie Bankhead Owen, director, and Peter Brannon, curator.35 Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, they corresponded with museum professionals, including Edgar P. Richardson, Detroit Institute of Arts director, who wrote: “I see no resemblance . . . to Allston’s portrait style. It is difficult to fit into the chronology of the artist who left South Carolina as a boy of eight and returned to the South only once.”36 Despite this, a 1959 Antiques magazine article by Agnes Dods reattributing it to Nathan Negus incited increasingly tense correspondence.37 Dods ruffled feathers on two counts; she was female and a Yankee. Brannon described her as a “New Englander [who is] not very well conversant with our geography,” and who “doesn’t know very much about Georgia history.”38 More significant, Allston’s Southern identity was not shared with Massachusetts-born Negus. In 1959 Montgomery, racial tensions were high, the bus boycotts had recently ended (1956), and white Southern identity was perceived as under attack by Northern agitators. Subsequently, the reattribution of McIntosh’s portrait to Northern painters by a Northern scholar threatened to undermine deeply held racist ideologies about Southern identity. The archives accepted Negus’s authorship in 1970; however, it remains only “attributed” to him, despite the evidence presented in his journal.

The Negus portrait played a dynamic role in these reconsiderations of McIntosh’s legacy. In many ways, his portrait and biography imply that biracial men at the antebellum frontier enjoyed a remarkable amount of cultural and social freedom and that, when it came to Indigenous identity, race was a fairly mutable construct. As historian Andrew K. Frank argues:

McIntosh obtained his prominence within Creek society because of his ability to balance carefully two identities—that of a Creek and that of an American—and his ability to translate the advantages provided by his American identity into sources of power in Creek society . . . he strategically asserted the identity that would best suit the circumstances . . . his rise to power . . . signified the opportunities afforded to individuals who could reconcile native and American identities.39

As a cultural broker, McIntosh was skilled at moving between increasingly antagonistic realms. Traversing Native and American societies, he became all things to all people.

This duality is clearly manifested in the 1821 portrait in which McIntosh’s ambivalent gestures toward the landscape can alternately be read through his position as a United States treaty negotiator or as Mvskoke-Creek. He is both a new settler to Indian Springs and tied to the land via generational heritage. His clothing combines an American shirt and tie and Native regalia. He physically presents as racially white and Mvskoke-Creek. Significantly, McIntosh does not make eye contact with the viewer; he looks to his left with a clear gaze—his attention caught by something outside the frame. The position of his feet invites the viewer into the work and directs us toward the landscape. Whoever “we” are, the painting serves as an open invitation to look along with McIntosh and see through his eyes.

Cite this article: Naomi Slipp, “Traversing Two Cultures: A Portrait of William McIntosh, Southern Slave Owner and Lower Creek Chief,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10640.

PDF: Slipp, Traversing Two Cultures

Notes

- There is one short, unsourced article on the painting: Laquita Thomson, “Nathan Negus and the Portrait of William McIntosh,” Alabama Heritage 50 (Fall 1998): 44–46. Historical scholarship on McIntosh includes Warwick Lane Jones, “A Portrait of William McIntosh: Leader of the Creek Nation,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 74 (Spring 1996): 76–95; Benjamin W. Griffith Jr., McIntosh and Weatherford: Creek Indian Leaders (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998); George Chapman, Chief William McIntosh: A Man of Two Worlds (Atlanta: Cherokee Publishing, 1988); and “The Rise and Fall of Chief William McIntosh,” Georgia Public Broadcasting, video, 5:54 min., accessed September 17, 2020, https://www.gpb.org/georgiastories/stories/story_of_chief_william_mcintosh. For a similar study of a portrait of Nahetluc Hopie, see Kathryn Braund, “A Southern Portrait by Another Kind of Artist,” American Nineteenth Century History 17, no. 2 (2016): 235–39. ↵

- Niles Weekly Register, November 7, 1818, 176, as quoted in Michael D. Green, The Politics of Indian Removal: Creek Government and Society in Crisis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982), 55. ↵

- On slavery and Native Americans, see Fay A. Yarbrough, Race and the Cherokee Nation: Sovereignty in the Nineteenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008); Christina Snyder, Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Age of Jackson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); and Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). ↵

- Andrew K. Frank, Creeks and Southerners: Biculturalism on the Early American Frontier (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 104. ↵

- Kathryn H. Braund, Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993). ↵

- On the Federal Road, see Henry deLeon Southerland and Elijah Brown, The Federal Road through Georgia, the Creek Nation and Alabama, 1806–1836 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989); Kathryn H. Braund, Gregory A. Waselkov, and Raven M. Christopher, The Old Federal Road in Alabama: An Illustrated Guide (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2019); and Angela Pulley Hudson, Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). ↵

- Claudio Saunt, “Taking Account of Property: Stratification among the Creek Indians in the Early Nineteenth Century,” William and Mary Quarterly 57, no. 4 (October 2000): 733–60. ↵

- Watson W. Jennison, Cultivating Race: The Expansion of Slavery in Georgia, 1750–1860 (Louisville: University Press of Kentucky, 2012), 197. ↵

- Christopher Haveman, “Creek Indian Removal,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, accessed September 17, 2020, http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2013; and Theda Perdue, “The Legacy of Indian Removal,” Journal of Southern History 78, no. 1 (February 2012): 3–36. ↵

- Website for the Poarch Creek Indians, accessed September 17, 2020, http://pci-nsn.gov/wordpress. ↵

- Mary Ann Stankiewicz, Developing Visual Arts Education in the United States (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016), 16. ↵

- Nathan Negus papers, 1819–1822, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, as quoted in Stankiewicz, Developing Visual Arts Education, 17. ↵

- Nathan wrote to his brother: “I think we could make money very fast in the southern states for a year or two.” Thomson, “Nathan Negus and the Portrait of William McIntosh,” 44. ↵

- Typescript of Negus journal entry, as quoted from Agnes Dodd to Peter Brannon, undated letter, Alabama Department of History and Archives, director’s files. ↵

- Only nine paintings are attributed to Nathan Negus in the Smithsonian Institution Research Information Systems (SIRIS) database; three entries appear to reference an 1820 self-portrait at the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA. Smithsonian American Art Museum Arts Inventories Catalog, SIRIS, accessed September 17, 2020, https://siris.si.edu. ↵

- Martha F. Norwood, The Indian Springs Hotel as a Nineteenth-Century Watering Place (Atlanta: Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 1978); and Sherry L. Boatright, The McIntosh Inn and Its Place in Creek Indian History (Atlanta: Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 1976). ↵

- Timothy Shannon, “Dressing for Success on the Mohawk Frontier,” William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 1 (January 1996): 13–42. ↵

- On Southeastern Woodlands dress, see Gaylord Torrance, Ned Blackhawk, and Sylvia Yount, Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018); and Lois Sherr Dubin, “The Visual Language of Beadwork,” Cowboys & Indians (July 2016), accessed September 17, 2020, https://www.cowboysindians.com/2016/07/the-visual-language-of-beadwork. Contemporary Native artists continue the tradition of Southeastern Woodlands beadwork, including Choctaw artist Jerry Ingram and Martha Berry of the Cherokee Nation. America Meredith, “Stitches in Time: The Rebirth of Southeastern Woodlands Beadwork,” First American Art Magazine (March 2015), accessed September 17, 2020, https://firstamericanartmagazine.com/southeast-beadwork. ↵

- This feature is also seen on a red bandolier bag from North Carolina in the collection of the Denver Art Museum (1971.406), illustrated in Susan G. Power, Art of the Cherokee: Prehistory to the Present (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007), 102. ↵

- W. Richard West Jr., “Preface,” in Lois Sherr Dubin, Floral Journey: Native North American Beadwork, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: The Autry Museum of the American West in association with University of Washington Press, 2014), n.p. ↵

- Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall, “McIntosh: A Creek Chief,” in History of the Indian Tribes of North America (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1836), 1:129–33; William Gilmore Simms to the City Gazette, March 31, 1831, as quoted in Andrew K. Frank, “The Rise and Fall of William McIntosh: Authority and Identity on the Early American Frontier,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 86, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 33. ↵

- Frank, “Rise and Fall of William McIntosh,” 33. ↵

- Kevin Muller, “From Palace to Longhouse: Portraits of the Four Indian Kings in a Transatlantic Context,” American Art 22, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 26–49. ↵

- “From all evidence . . . this brilliant outfit was deployed for show rather than regularly worn. . . . {Such individuals} did not innovate hybrid dress regimes; nor, except superficially, {did} they accept apparel that would assimilate their sartorial appearance to that of the ‘savage’ or the enslaved.” Robert S. DuPlessis, The Material Atlantic: Clothing, Commerce, and Colonization in the Atlantic World, 1650–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 229. See also Ruth B. Phillips, “Reading and Writing between the Lines: Soldiers, Curiosities, and Indigenous Art Histories,” Winterthur Portfolio 45, nos. 2/3, Summer/Autumn 2011): 107–24; Beth Fowkes Tobin, “Wampum Belts and Tomahawks on an Irish Estate: Constructing an Imperial Identity in the Late Eighteenth Century,” Biography 33 no. 4 (2010): 680–713. ↵

- The middle ground is described by Elizabeth Hutchinson as “a site of intercultural contact and exchange which, while not without conflict, required participants to become familiar enough with the values and reasoning of their interlocutors to use them to achieve their own ends.” See Hutchinson, “From Pantheon to Indian Gallery,” Journal of American Studies 47, no. 2 (May 2013): 318. See also Stephanie Pratt, American Indians in British Art (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005); and Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). ↵

- Kristine K. Ronan, with Allan McLeod, “Káma-Kapúska! Making Marks in Indian Country, 1833–34,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2019.18.2.23. ↵

- Hutchinson, “From Pantheon to Indian Gallery,” 313. ↵

- This may have been made on a diplomatic mission to Washington, DC. Karl Bodner and George Catlin are also known for their portraits of Native Americans. See Norman K. Denzin, Indians on Display: Global Commodification of Native America in Performance, Art, and Museums (London: Routledge, 2016); Herman J. Viola, Diplomats in Buckskins: A History of Indian Delegations in Washington City (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995); and Andrew J. Cosentino, The Paintings of Charles Bird King (1785–1862) (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977). ↵

- Nancy Hagedorn, “‘Faithful, Knowing, and Prudent’: Andrew Montour as Interpreter and Cultural Broker, 1740–1772,” in Between Indian and White Worlds: The Cultural Broker, ed. Margaret Connell Szasz (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 44. See also James H. Merrell, “The Cast of His Countenance: Reading Andrew Montour,” in Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America, ed. Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel, and Fredrika J. Teute (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 13–39; and Timothy Shannon, “Dressing for Success on the Mohawk Frontier,” William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 1 (January 1996): 13–42. ↵

- Jennison, Cultivating Race, 278–79. ↵

- Albert James Pickett, History of Alabama and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period (Sheffield, AL: Robert C. Randolph, 1896), 479; and Lucian Lamar Knight, A Standard History of Georgia (Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1917), 3:1379. ↵

- Thomas McAdory Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing, Company, 1921), 2:751; and Henry S. Marks, Alabama Past Leaders (Huntsville, AL: Strode Publishers, 1982), 192. ↵

- Peter Brannon, typed unpublished manuscript for “Historical Quarterly,” Alabama Department of History and Archives, director’s files (hereafter director’s files). ↵

- David I. Bushnell Jr. to Marie Bankhead Owen and Peter Brannon, correspondence, September 11, 1924; Marie Bankhead Owen to unidentified, request for photography, correspondence, August 26, 1946, director’s files. ↵

- The archives have recently turned a critical eye on their institutional history and begun to reappraise the legacy of Marie Bankhead Owen, who was director from 1920 to 1955. Jay Reeves, “Alabama Archives faces its legacy as Confederate ‘attic,’” AP News, September 21, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/montgomery-race-and-ethnicity-alabama-racial-injustice-archive-06fba79572a8e3a9faf53f2789da3a0a. ↵

- Edgar P. Richardson, director, Detroit Institute of Arts, to Brannon, correspondence, July 16, 1956, director’s files. ↵

- Agnes Dods, “Joseph and Nathan Negus, Itinerant Painters,” Antiques 76 (November 1959): 434–37. ↵

- Brannon to Mrs. Smith, correspondence, February 29, 1960, director’s files. Brannon also wrote to Antiques discrediting the new attribution. ↵

- Frank, “Rise and Fall of William McIntosh,” 24, 48. ↵

About the Author(s): Naomi Slipp is Associate Professor of Art History at Auburn University at Montgomery