Roadside California: Tressa Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, Theme Parks, and Art Tourism in the Golden State

PDF: Smith, Roadside California

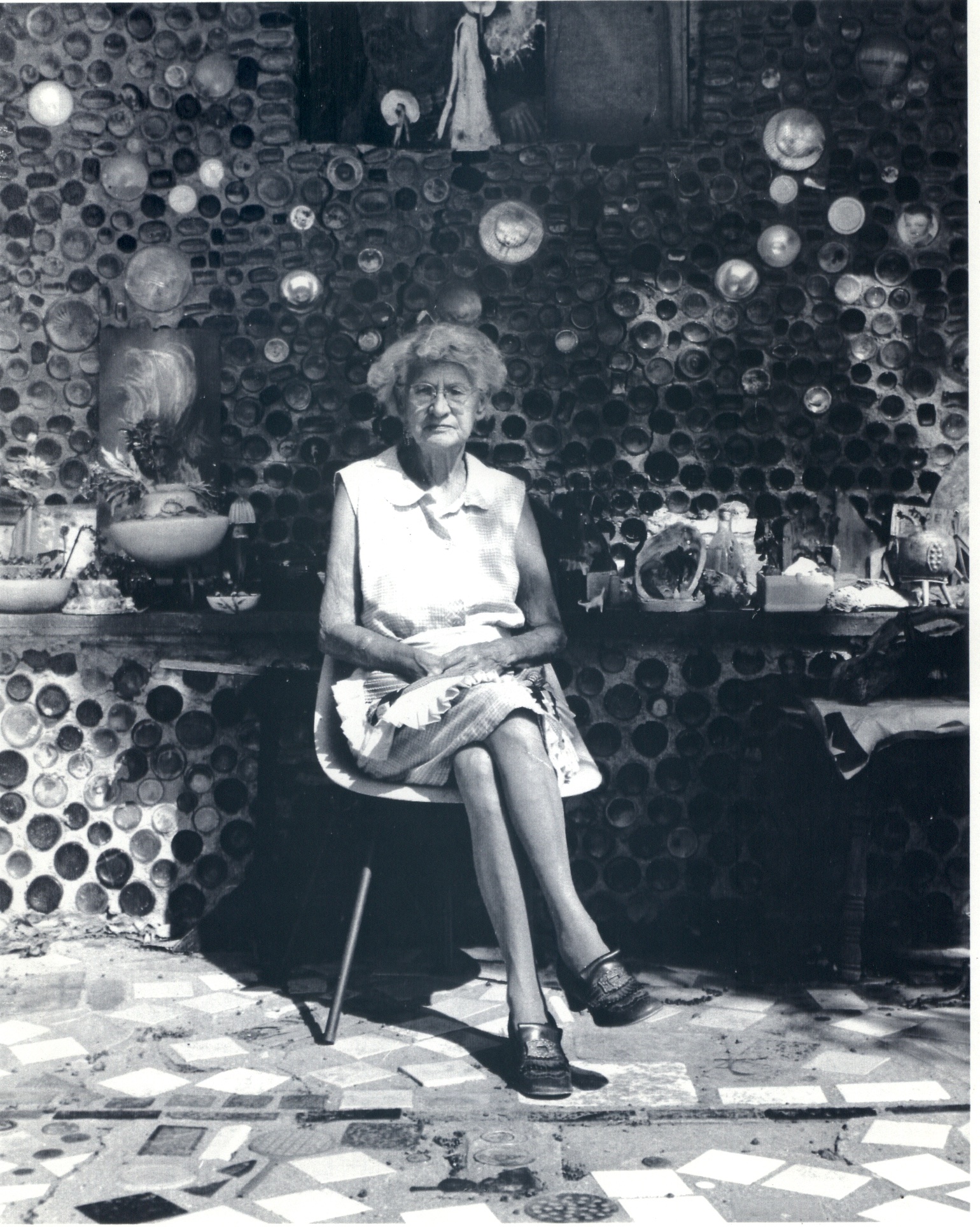

In the mid-1950s, along California State Route 118 in Simi Valley, Tressa “Grandma” Prisbrey began building the Bottle Village—a multistructure complex made of cement mortar and glass bottles that she intended as a parallel to the then-newly established and nearby Disneyland, Marineland, and Knott’s Berry Farm theme parks.1 Donning a large sunhat, she would climb in a dusty Studebaker pickup truck and drive (without a license) to the town dump, where she salvaged bottles, wooden beams, and other structural building elements (fig. 1).2 Prisbrey embellished her site with dolls, car parts, ceramics, furniture, and reclaimed fabric—all found at the dump or gifted by tourists. She used small plastic objects and broken tiles to mosaic both the interior floors and exterior walkways (fig. 2), employing a similar “magic” and delight in discovery that one might experience at Disneyland. In her self-published brochure, which she autographed and distributed to visitors for the price of one dollar, she wrote: “Anyone can do anything with a million dollars—look at Disney. But it takes more than money to make something out of nothing, and look at the fun I have doing it.”3

Fig. 1. Clip from Allie Light and Irving Saraf, Grandma’s Bottle Village: The Art of Tressa Prisbrey, part of the Visions of Paradise film series (San Francisco: Light-Saraf Films, 1982), 28:30. Courtesy of Allie Light. Full video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=inOvmkF1fLA&list=PL7IzWuVD2YXAEx2b3tp_xH5GdIw_ODOPt&index=2&t=389s

In “making something out of nothing”—thirteen standalone structures and numerous sculptures from reclaimed materials—Prisbrey intentionally engaged a newly mobile demographic traversing southern California’s expanding roadways during the mid- to late twentieth century. I employ the word “intentional” to dispel misconceptions that Prisbrey was a passive agent in her rise to roadside notoriety or that the Bottle Village was born out of isolation or visionary occurrence. Much of Prisbrey’s history, as it has circulated through exhibition catalogues, frames the highway as her road to discovery—a one-way street that leaves little room for her own agency and has instead cemented her status as “outsider,” “naïve,” “folk,” or “visionary.”4 Her archival materials reveal that the Bottle Village was practical and purposeful, a home and occasionally a lucrative tourist attraction located along a major regional thoroughfare.

Prisbrey mirrored other regional theme park advertising strategies that similarly capitalized on the transportation infrastructure boom facilitated by the Federal Highway Act of 1956, yet she also suffered its unintended consequences when developers deemed the Bottle Village incompatible with a suburbanizing Simi Valley. This essay examines Prisbrey’s Bottle Village as part of southern California’s roadside culture during the latter half of the twentieth century, arguing that the highway was a nuanced facilitator within the once-agricultural region.

To Grandma’s House We Go: Tressa “Grandma” Prisbrey and the California Roadside

Midcentury women artists who fell under the rubric of self-taught artists were predominantly caretakers, domestic workers, or employees in service industries. In the case of Prisbrey and other women-identified environment builders, such as Mollie Jenson, Nellie Mae Rowe, Mary T. Smith, and Kea Tawana, education came in the form of lived experience, which was (and still is) classed secondary to formal pedagogical models, such as high school and college. Prisbrey wielded her lived-experience-as-education in two ways: first, to physically build Bottle Village and, second, to engage a generation of tourists eager to see a hand-built glass wonderland made by a woman in her sixties.

In 1960, California State Route 118 was the only east-west highway traversing Simi Valley and the main connector between the San Fernando Valley and the city of Los Angeles.5 The Bottle Village, located at 4595 Cochran Street, was conveniently situated a block down and parallel to the increasingly busy highway. Prisbrey chose the location with practicality in mind. After many years of itinerant living in a mobile home, she sought permanent roots in Ventura County’s Simi Valley (adjacent to Los Angeles County). Anchored by her younger sister, Hattie, and son Frank, who lived nearby, as well as a recent marriage to her second husband, Albert, Prisbrey “took the wheels off the trailer and hid them” to prevent any “further meandering about the country” in 1955.6

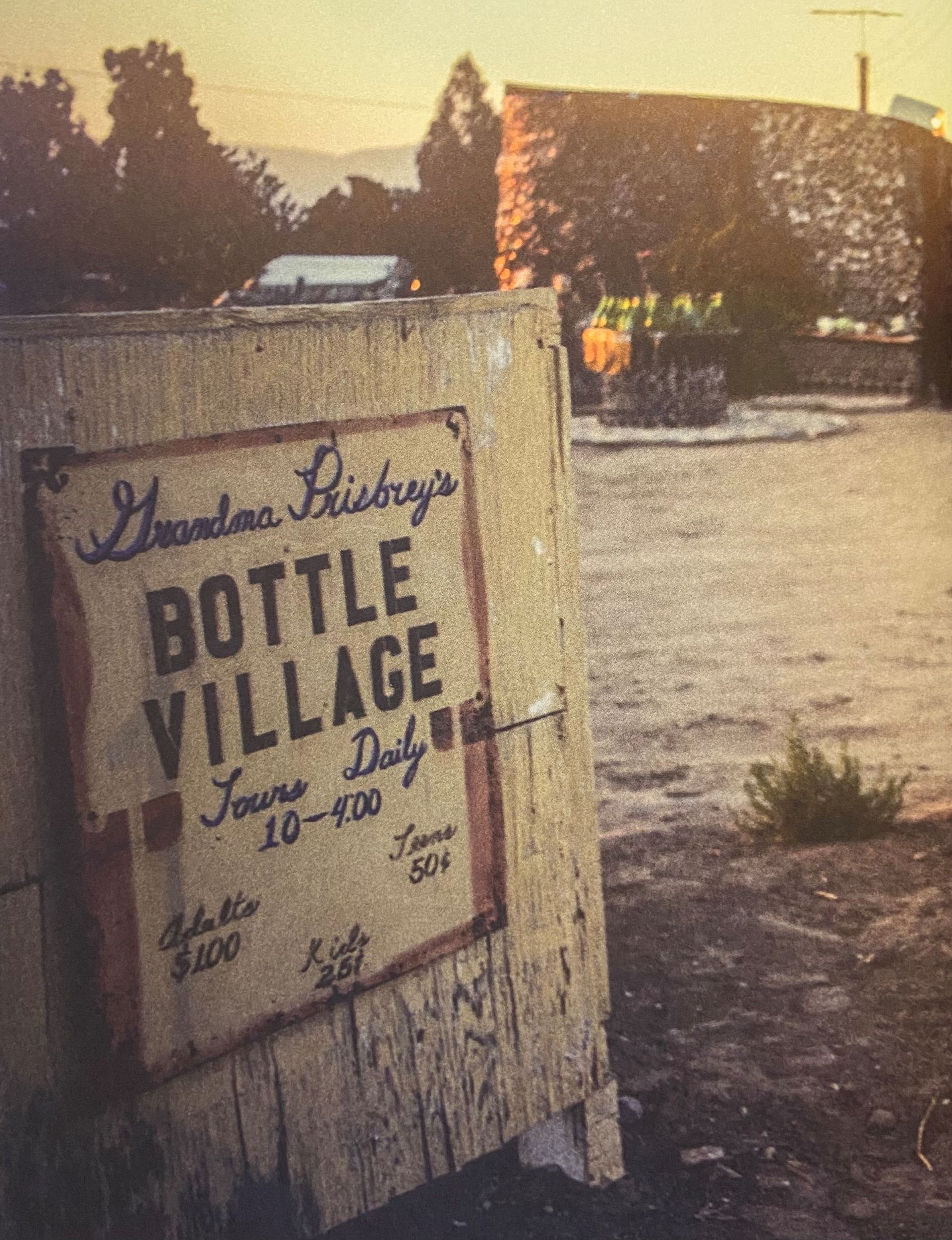

The Bottle Village, however, was not Prisbrey’s first attempt at building. After realizing that the luxurious three- and four-bedroom tract houses in Simi Valley exceeded her meager salary from the Tapo Citrus packing house, she began experimenting with cement block foundations to build a home of her own in the late 1940s. She sold the home shortly after its completion to fund a stomach ulcer surgery, using the remaining profits to purchase the lot on Cochran Street.7 For her next construction project, Prisbrey looked to recyclables: glass bottles and other materials were plentiful at the dump, located right down the street, and she found that cement mortar was priced far cheaper than premade blocks. The discards of daily life, shimmering under the scorching valley sun at the dump, could be repurposed into a site to store her growing collection of pencils and dolls—and perhaps become something lucrative. “I got to thinking about various things I could do to our one-third acre which could make it pay,” she writes.8 Employing skills learned during her time working as an aircraft assembler during World War II, she began building the structures that would comprise her primary residence and roadside attraction. She spent the next few years layering cement and bottles by hand—with some assistance from her son Frank and grandsons for the roofing components—and the public began to take notice: “I liked it, and so did other people who rubbered in to see what I was doing, and stayed around to give me ideas on how to do it.”9 In 1959, she applied for and was granted an outdoor advertising display permit by the county (fig. 3).10 On her newly minted Bottle Village sign, tours were originally advertised as ten cents for children and a quarter for adults, but the cost gradually increased over time.11 She made the executive decision to begin charging admission after numerous bouts of theft—likely a result of the prolific increase in visitors after the site was listed as a must-see by the Automobile Club of Southern California.12

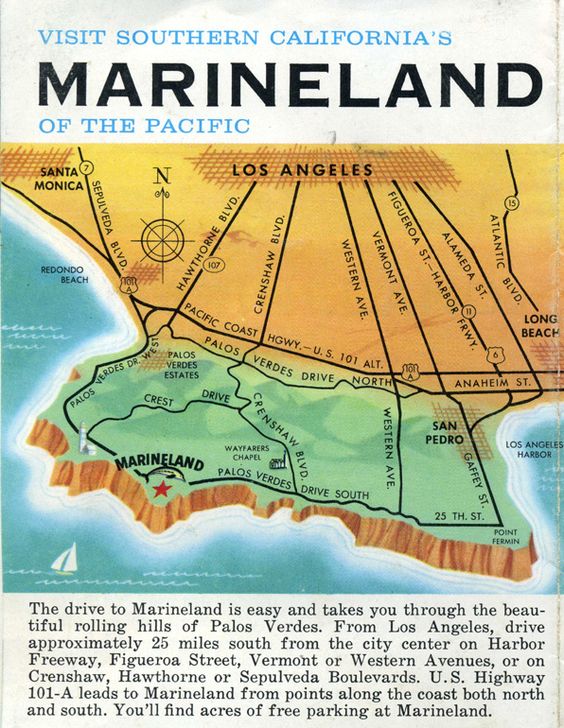

Prisbrey’s self-promotion strategies mirrored those of roadside theme parks like Disneyland, Marineland, and Knott’s Berry Farm, who similarly capitalized on an influx of automobile traffic to Orange and Los Angeles Counties. Both local and national audiences were encouraged by travel brochures to traverse ocean-view drives on their way to Marineland, located on the scenic Palos Verdes peninsula, advertised as an idyllic coastal juncture of Santa Monica, Los Angeles, and Long Beach during the 1950s (fig. 4). Knott’s Berry Farm originated as a roadside fruit stand and restaurant alongside Grand Avenue in Buena Park (Orange County), but when guests’ wait times became prohibitive in the late 1930s, its founders introduced performers, rock gardens, and replicas of historic interiors as distractive entertainment.13 Walt Disney asserted his influence on the Orange County roadway system in myriad ways: Disneyland actively advertised cars—and oil companies—to a consumer public through park displays and programming in a mutually beneficial arrangement. Television episodes, like “Magic Highway, U.S.A.” (1958) of the Magical World of Disney program series (1956–97), lauded the political and economic merits of highway expansion while assuaging the public’s anxieties around traffic congestion and physical displacement.14 Early episodes meticulously covered the park’s construction, highlighting its role in the developing economy of Orange County. In its first episode (which aired October 27, 1954), Walt Disney narrates the park’s organization: four “cardinal realms” comprising Adventureland, Tomorrowland, Fantasyland, and Frontierland.

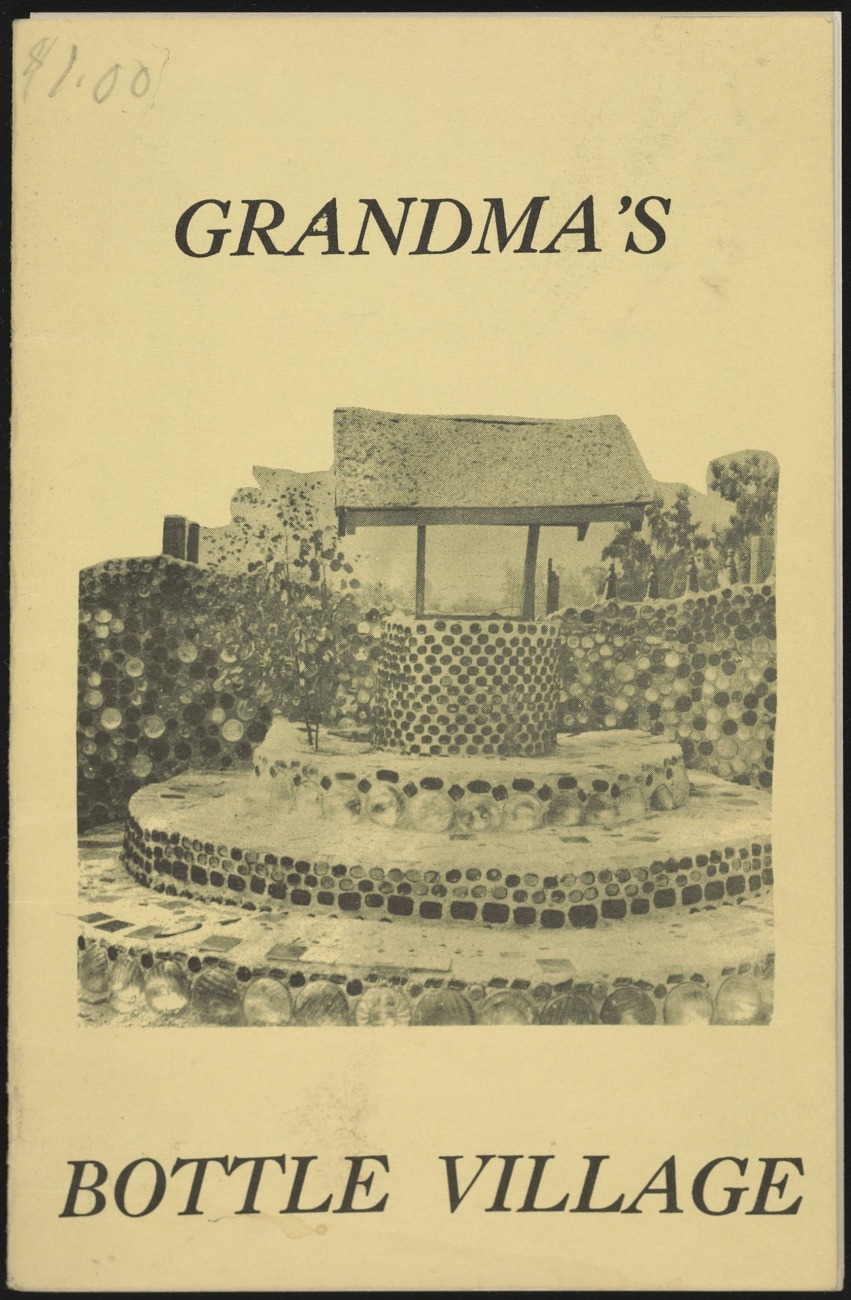

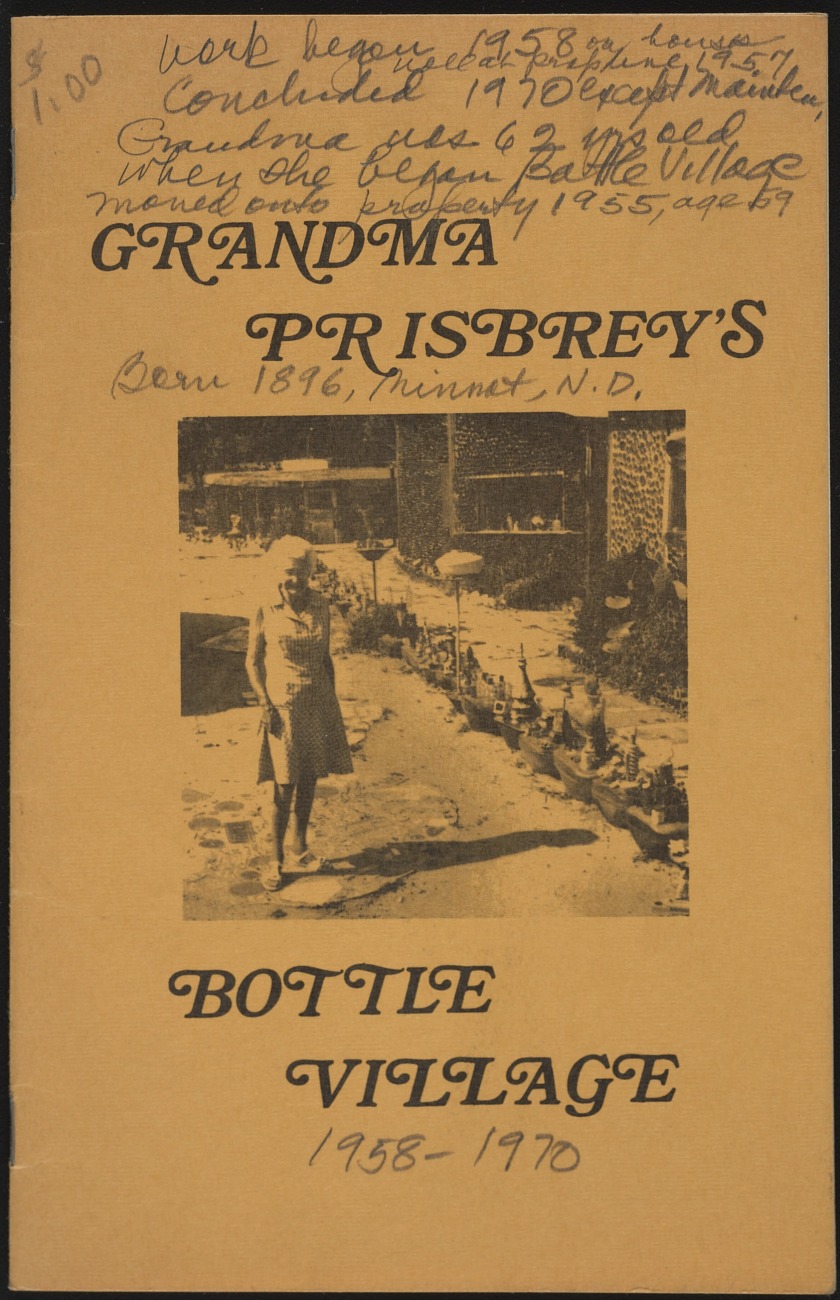

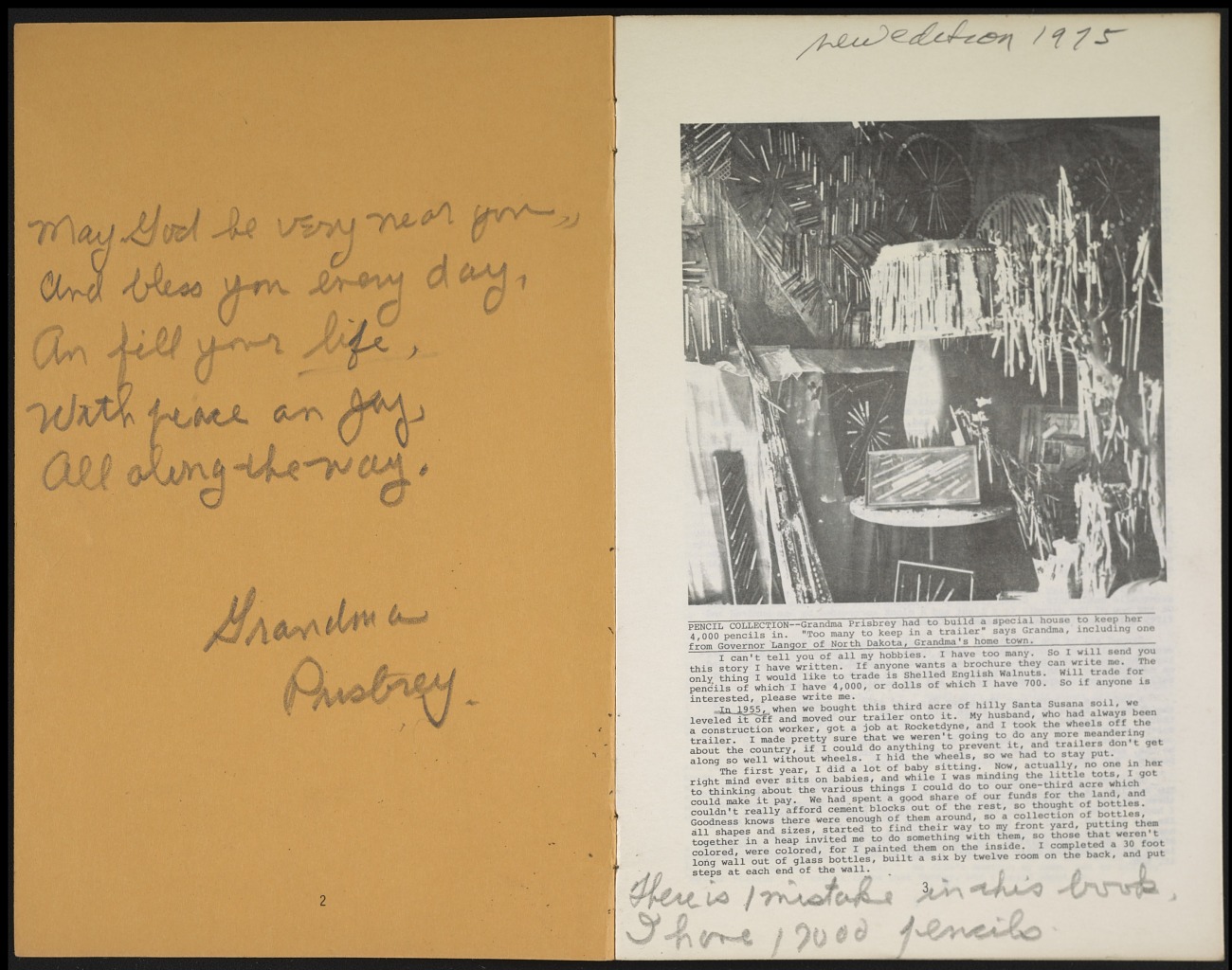

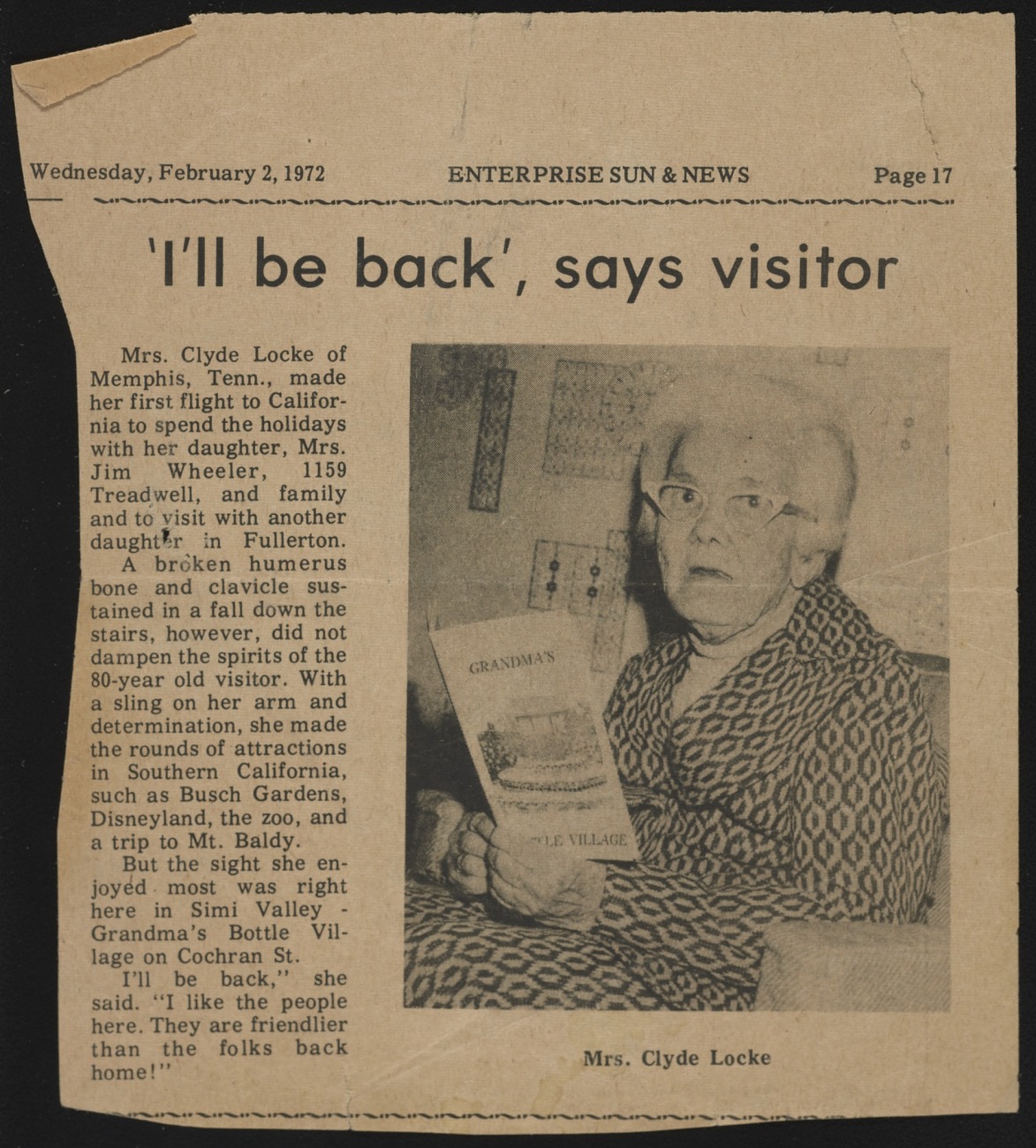

Prisbrey adopted a similar narrative and organizational method in her visitors’ brochure, first printed in 1960. “Grandma’s Bottle Village” was a yellow paper guide that, like Disney’s tour, led visitors through Bottle Village’s layout. Akin to travel brochures of the time, it combined photographs of each Bottle Village structure with the story and purpose of its creation. The brochure was equal parts catalogue and souvenir; Prisbrey often inscribed the interior or the front cover with a quote and her signature, sometimes adding short factual details about the dates of the Bottle Village’s construction. When architectural historian Esther McCoy visited the Bottle Village in July 1974, she left with two copies (figs. 5 and 6): one cover shows Prisbrey’s bottle and car headlight “well,” visible from the entrance on Cochran Street; the other a photograph of Prisbrey smiling, sharply dressed, standing on a mosaic heart.15 The interior cover page is signed “Grandma Prisbrey,” with an accompanying quote and correction, noting that her expansive commemorative pencil collection now totaled seventeen thousand in number, not four thousand (fig. 7). For some California tourists, the brochure functioned akin to theme-park ephemera, such as tickets, maps, trinkets, and apparel, which one purchased to memorialize epic excursions. Mrs. Clyde Locke, a tourist from Memphis, Tennessee, is depicted in Simi Valley’s local newspaper on February 2, 1972, holding Prisbrey’s brochure under the headline “I’ll be Back” (fig. 8). At age eighty and perhaps a grandmother herself, Locke had “made the rounds of attractions in southern California, such as Busch Gardens, Disneyland, the zoo, and a trip to Mt. Baldy,” but she found Bottle Village the most worthwhile.16 While Prisbrey could not match the political and financial capacity of southern California’s theme park trifecta, printing brochures was a relatively inexpensive—and personal—way to communicate her story to a mobile public.

The Bottle Village visitor experience hinged on Prisbrey’s storytelling, which spanned humorous accounts of her early life in North Dakota to tales of the profound loss she experienced throughout her lifetime.17 Prisbrey’s engagement with roadside visitors as “grandma” cultivated a buzz around Bottle Village, much like the way Knott’s Berry Farm and Disneyland relied on a cast of characters to reinforce a welcoming, jovial atmosphere. Her adoption of a familial title as an appellate was intentional: it conveyed her caretaking background to strangers. Tourists overheard her grandchildren using it during visits and began referring to Prisbrey through the moniker. In turn, she titled her brochures and roadside signs “Grandma’s Bottle Village.” In addition to being a biological grandmother, Prisbrey acted out the archetype of midcentury matriarch by serving lemonade and freshly baked cookies to Bottle Village tourists. Numerous photographs show her in a frilled half-apron—a practical garment that protects its wearer’s clothing and, for many in the 1960s, signified the warmth and hospitality of a grandmotherly figure (fig. 9). On tours, visitors heard about the welding and riveting skills Prisbrey learned while working as a parts assembler for Boeing aircraft in Seattle during World War II or about how she entertained politicians at a local diner with her piano and singing talents; she was even briefly engaged in North Dakota politics (the catalyst for her first collecting endeavor, through which she acquired autographed campaign pencils). Over the years, her story encompassed tragedy, too: she raised seven children and witnessed the death of six of them during her lifetime—in addition to two husbands. When two of her children were dying of cancer, she constructed small rooms for them on the property—a sort of self-made hospice—where they would be surrounded by the radiant, colorful light that streamed through the glass-bottle walls at sunset.18 While each of these personal and professional elements of her life might warrant its own venue, they were presented through the “grandma” persona she intentionally cultivated for Bottle Village visitors.

Art Tourism at the Bottle Village

The presence of tourists factors frequently in the Bottle Village’s archive and Prisbrey’s scattered archival material. Prisbrey often involved her audience in her environment’s creation, incorporating their interactions into her tour stories as a way to reinforce the site’s cultural importance. As one visitor is quoted in her brochure: “You know, when my folks were here, from Indiana, I brought them over to your place, and then took them on a tour of the spectacular things such as Knott’s Berry Farm, Marineland, and Disneyland. The only thing my dad talked about was the Bottle Village.”19 Some opted for only a quick self-guided tour, while others brought materials or offered (sometimes unwelcome) artistic direction. For example, brochure readers learn that Prisbrey received an offer to trade her antique chandelier for a new model (she declined), and other visitors encouraged her to exhume a brown plaque depicting Queen Victoria from the Rumpus Room’s floor: “Many people want me to dig it out and sell it to them, but I like it where it is. And I don’t think I am being a bit disrespectful to Her Majesty, either.”20

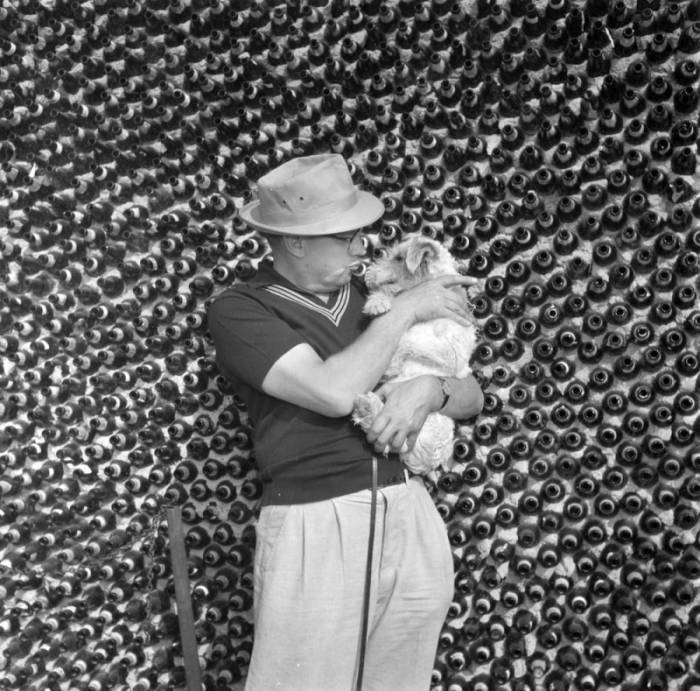

Photographs from the Valley Times photo collection show the extent to which tourists considered Prisbrey’s Bottle Village a major California roadside landmark. In one image, two tourists stage a portrait in front of the Round House’s tall bottle façade (fig. 10). Both are shown in profile looking off to the right; one grasps a wearable camera that indicates photographs were a common souvenir for art-minded tourists. Another staged photograph—with the same bottle background—frames a well-dressed man and his small white dog in a loving cuddle (fig. 11). The same man and canine appear in another photograph, posed atop the Bottle Village’s entryway “well” composed of car headlights and bottles (fig. 12).

The Bottle Village also appealed to a different kind of roadside tourist—namely artists—who interpreted Prisbrey’s site as a progenitor for feminist placemaking strategies of the 1970s or, in the case of Betye and Alison Saar, as materially connected to their own assemblage practices. The Los Angeles Woman’s Building held a Bottle Village exhibition in 1976, during which participants of the building’s Feminist Studio Workshop recreated part of a bottle wall and invited Prisbrey to speak about her life and work.21 For many women artists interrogating the ways gender operated in private and public spaces, Prisbrey’s Bottle Village was a protofeminist predecessor to the performance and installation work they developed through the Feminist Studio Workshop. By the time Betye Saar visited Bottle Village with her Otis Parsons graduate students in 1980, she had already been nurturing an interest in self-taught artists’ work, specifically those using reclaimed objects.22 Her daughter, Alison, made the work Soul Service Station (fig. 13) in homage to both the Bottle Village and Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers (in Los Angeles).23 Soul Service Station comprises four separate mosaic objects: a tall cloud-shaped sign, a figurative sculpture of a Black man sitting contemplatively in a chair, a blue gas pump fabricated from glass bottles and wood, and a small white dog with pronounced teeth. Saar notes that Bottle Village’s roadside location was her impetus to place “art outside the safety of the museum and open to a public who would, by chance, pass it on the road.”24

By Way of a Conclusion: Roadside Repercussions

Prisbrey’s Bottle Village is not exclusively a highway success story. Its extended history reveals the tensions between the notions of the highway as connector or as disruptor. Often, progressivist roadway narratives belie the complex and increasingly contentious relationship between quickly developing highway systems and artist-built environments—specifically those built and sustained by women. As the urban historian Dolores Hayden argues, such histories of the postwar transportation industry center around the housing and travel needs of upper-class men.25 The roadway was a means of self-advertising and public engagement for Prisbrey, but as it was expanded through various government-funded highway initiatives, it also brought new neighbors—many dismayed by what they considered to be an inconvenient and aging eyesore prime for elevated real estate.

News articles document that Prisbrey’s gender and age were used against her, threatening the Bottle Village’s existence. After selling the property to a sympathetic buyer in 1972 and living briefly with an ailing son in Oregon, she returned as a tenant and caretaker in 1974.26 However, when the new owner defaulted on loan payments, the Bottle Village was put up for public auction and acquired by a large development company as the site for a potential condominium in 1981.27 The construction of big multiunit living complexes was a new strategy devised by the city of Simi Valley to increase its tax revenue and attract large industrial and manufacturing companies to the area. Their plan worked: by 1980, a number of sizable corporations made Simi Valley their headquarters. Farmers Insurance Company, for example, erected a five-story office on Cochran Street two miles west of Bottle Village. Demolition of Bottle Village for tax-generating corporations was, according to the development company’s president Ollie Phillips, “a business problem, plain and simple.”28 Phillips is quoted in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner: “I don’t feel sorry for her [Prisbrey]. She wants a free load. Listen, I bought the property—I didn’t buy an 85-year-old lady.”29 While the Bottle Village was saved thanks to numerous preservation efforts, mostly by those of the Preserve Bottle Village Committee (established in 1979), it was severely damaged by the 1994 Northridge Earthquake and remains in precarious condition today, despite being on the National Register of Historic Places.30

In exhibition catalogues, artist-built environments have long been linked to postwar roadside exploration, predominantly through the perspectives of those sitting behind the wheel. Erika Doss’s essay in Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds: Built Environments of Vernacular Artists questions the ways such unconventional structures reinforce a “national imaginary” around the discovery of so-called outsiders in the United States. She writes:

Stifled by the sameness of life in the suburbs, or “mean regular houses” and daily routines of Starbucks and strip malls and office towers, Americans journey to vernacular environments to see and touch and be subsumed by the palpable stuff of the nation’s soul, including its much celebrated ethos of individuality and its romantic preference for rebels.31

In the early twentieth century, the search for an “antimodern” was driven—quite literally—by a similar colonialist impulse for the “rare, the authentic, and ‘primitive,’ the opposite, the Other,” writes Kenneth Ames.32 Collectors from across the United States hit the road in search of “folk art,” a loosely defined category that, according to those doing the collecting, could encompass anything from anonymously produced nineteenth-century furniture to the inscribed vessels made by the enslaved potter in Edgefield, South Carolina known as Dave (later identified as David Drake).

Doss’s line of inquiry stopped short of asking how builders themselves viewed their audiences and the repercussions of urban—and suburban—sprawl engendered by highways. Until recently, little critical inquiry has aimed to counter the discovery narratives woven throughout environment builders’ histories.33 Locating their perspectives can prove challenging: oftentimes archival material is scant; first-person narratives are nonexistent, since family members are long gone; and little documentation of their processes exist in written form. Self-taught women environment builders, like Prisbrey, were consistently othered and ignored even as their sites became popular with a burgeoning mobile demographic. As curator Leslie Umberger argues in her recent essay “Housewives, Witches, Beauty Queens, and Conjure Women: Locating the Practice of Self-Taught Women Artists,” age, gender, lack of formal education, social status, and rural location combined to render them art-world oddities—caught between the gendered stereotypes that made them appealing to mainstream artists and curators and, at the same time, minimized their aesthetic contributions.34

An overlooked component of Prisbrey’s archive demonstrates that in addition to tourists and art-world figures, she also gained a following of women her age with whom she kept in touch through letters. Some fellow grandmothers, like Peggy Sosnoski of New York, befriended her after discovering a shared love of collecting glass.35 Sosnoski had a daughter and grandchildren in the area and visited Prisbrey on occasion during the 1960s. Prisbrey sometimes confided to Sosnoski that playing the role of Bottle Village hostess—and groundskeeper—was becoming impossible due to her deteriorating physical health.36 She suffered broken ribs after a fall and complained frequently of the cold, lonely nights she had to endure during Simi Valley’s winters. Prisbrey was tired of working for free and needed income to pay her property taxes; some letters disclose that she requested payment in exchange for television appearances and casual interviews.37 These “interchanges” between grandmothers provide crucial counternarratives to those retooled for popular exhibition catalogues, which have historically flattened complex, multivalent histories into one-way streets.

By establishing Prisbrey as an innovator of California roadside tourism, I want to emphasize that artist-built environments are central to narratives of mobility and movement in postwar art of the United States. While not all environment builders working during the latter half of the twentieth century were receptive to inquisitive drivers, many, Prisbrey included, purposefully built alongside major highways to attract a network of visitors, which informed their practice and, in turn, influenced others. Their sites—and perspectives—shed light on the ways urbanization and gentrification affected artists working alongside the road.

Cite this article: Elizabeth Driscoll Smith, “Roadside California: Tressa Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, Theme Parks, and Art Tourism in the Golden State,” in “Reconsidering Art and Travel in America” (In the Round), ed. David Smucker, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18226.

Notes

- Before its current name—California State Route 118/ Ronald Reagan Freeway—in 1994, the portion of Route 118 that runs through Simi Valley was called the Simi Valley-San Fernando Valley Freeway. For a detailed investigation of Prisbrey’s materials and processes, see “Historic American Landscapes Survey: Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village,” National Parks Service, US Department of the Interior, HALS CA-42, https://memory.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/ca/ca3600/ca3678/data/ca3678data.pdf. ↵

- Verni Greenfield, Making Do or Making Art: A Study of American Recycling (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1986), 59. Some texts include Prisbrey’s sculptures as structures, bringing the total number of “buildings” to fifteen. ↵

- Tressa Prisbrey, “Grandma’s Bottle Village,” box 8 (Documents: Publicity Info & Materials), Correspondence, Bottle Village Documents, Preserve Bottle Village, California State Channel Islands, Ventura, CA (hereafter Preserve Bottle Village), 7. ↵

- Prisbrey was the only woman environment builder to be included the Walker Art Center’s Naives and Visionaries (1974)—the first major exhibition to showcase the homes and workspaces of self-taught artist-architects. Martin Friedman, the Walker Art Center’s director and curator of Naives and Visionaries, described these spaces as “the scruffy curiosa bordering the American highway . . . reptile gardens, pioneer villages, agate shacks . . . and . . . zoos”; Martin Friedman, introduction to Naives and Visionaries (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1974), 7. In the catalogue, he envisions some structures, such as Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, akin to the roadside fantasy attractions that proliferated during the twentieth century, beckoning tourists with colossal sculptures and brightly colored architecture. Friedman was likely referencing what photographer John Margolies began capturing on film in the late 1960s: larger-than-life ducks, dogs, dinosaurs, and doughnuts; historic hot dog stands; hand-painted signs; castle motels; and putt-putt golf courses; all strategically built to sell goods and services alongside the United States’ new and expanding roadways. ↵

- Patricia Havens, Simi Valley: A Journey Through Time (Simi Valley, CA: Simi Valley Historical Society and Museum, 1997), 372. ↵

- Prisbrey, “Grandma’s Bottle Village,” 2. Often, dating Prisbrey’s activities is challenging due to conflicting information, but archival records show she bought the Corcoran Street property in 1955 and began construction on the Bottle Village in 1956. ↵

- Prisbrey Time Line, October 30, 1999, SPACES Archives, Kohler, WI. ↵

- Prisbrey Time Line, 1. ↵

- Prisbrey, “Grandma’s Bottle Village,” 2. Her sister Hattie said that Prisbrey mixed concrete by hand in a wheelbarrow and applied it directly on the bottles; see Grandma’s Bottle Village: The Art of Tressa Prisbrey, directed by Allie Light and Irving Saraf, part of the Visions of Paradise film series (San Francisco: Light-Saraf Films, 1982), 28:30. ↵

- Roadside Attraction Timeline, box 8, Correspondence, Bottle Village Documents, Preserve Bottle Village. ↵

- Prisbrey, “Grandma’s Bottle Village,” 4. ↵

- “You Haven’t Seen Simi Til . . . ,” Enterprise Sun & News, January 30, 1977. ↵

- Janey Ellis, “The History of Knott’s Berry Farm,” Knotts Berry Farm, accessed August 20, 2023, https://www.knotts.com/blog/2020/april/the-history-of-knotts-berry-farm. ↵

- Malcom Cook, “Magic Highways and Autotopias: Disney and Automobile Advertising,” in Animation and Advertising, ed. Malcom Cook and Kristen Moana Thompson, online edition (London: Palgrave Macmillan and Springer Nature Switzerland, 2019), 96, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27939-4. See also J. Philip Gruen, “Disneyland: Anaheim, California,” in American Tourism: Constructing a National Tradition, ed. J. Mark Souther and Nicholas Dagen Bloom (Chicago: Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, 2012). ↵

- McCoy was an essay contributor to the Naives and Visionaries exhibition catalogue; she wrote on Prisbrey’s Bottle Village and sketched a detailed rendering of the site’s layout. ↵

- “’I’ll Be Back’, Says Visitor,” Enterprise Sun & News, February 2, 1972, 17. ↵

- Prisbrey recounts many of these stories in the film Grandma’s Bottle Village: The Art of Tressa Prisbrey. ↵

- Greenfield, Making Do or Making Art, 69. Much of Greenfield’s research material was collected by speaking with both Prisbrey and her neighbors. ↵

- Prisbrey, “Grandma’s Bottle Village,” 6–7. ↵

- Prisbrey, “Grandma’s Bottle Village,” 11. ↵

- Prisbrey’s age and nonprofessional status intersected with two major aims of the Los Angeles Woman’s Building during the 1970s: one, to recover a lost generation of women artists, architects, and designers; and two, to demonstrate that education and expertise could be developed outside pedagogical institutions, like the studio art and architecture programs founded by and for men. ↵

- See, for example, Elizabeth Shepherd, ed., Secrets, Dialogues, Revelations: The Art of Betye and Alison Saar (Los Angeles: Wight Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1990). ↵

- Shepherd, Secrets, Dialogues, Revelations, 12; Saar, Soul Service Station (Roswell, NM: Roswell Museum & Art Center, 1986), n.p. ↵

- Saar, Soul Service Station, n.p. ↵

- Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820–2000 (New York: Random House, 2003), 5. ↵

- oadside Attraction Timeline & Biographical Information—Tressa Prisbrey, Bottle Village Documents, box 8, Correspondence, Bottle Village Documents, Preserve Bottle Village. ↵

- History of Bottle Village, box 8, Correspondence, Bottle Village Documents, Preserve Bottle Village. The auctioneer bought the property and promised to negotiate with the Preserve Bottle Village Committee for its transfer, but three weeks later sold it to Ernest Phillips Enterprises for $10,000 total profit. See Christopher Knight, “Bottle Village vs. The Bulldozer: Grandma Prisbrey’s Folk Art Treasure May Be Lost to Developers,” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, undated clipping, box 19, folder 34 (Printed Material, 1967–1981), Esther McCoy papers, Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. ↵

- Lennie La Guire, “Developer Planning to Raze Simi Valley’s Famed Bottle Village,” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, April 12, 1981. ↵

- La Guire, “Developer Planning to Raze Simi Valley’s Famed Bottle Village.” ↵

- The Preserve Bottle Village Committee was substantially aided by SPACES (Saving & Preserving Arts & Cultural Environments) and its director, Seymour Rosen. ↵

- Erika Doss, “Wandering the Old, Weird America: Poetic Musings and Pilgrimage Perspectives of Vernacular Art Environments,” in Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds: Built Environments of Vernacular Artists, ed. Leslie Umberger (New York: Princeton Architectural Press and John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 2007), 32. ↵

- Kenneth Ames, “The Term ‘Folk Art’ Once Again,” in Making It Modern: The Folk Art Collection of Elie and Viola Nadelman, ed. Margaret K. Hofer and Roberta J. M. Olson (New York: New York Historical Society Museum & Library, in association with D. Giles, 2015), 79. ↵

- A recent standout example is Emma Silverman’s article “All God’s Materials: The Dickeyville Grotto, Religion, and Roadside Attractions,” ArcGIS StoryMaps, May 3, 2021, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/3df9cfde88b2480b99f55027a05c93d6. ↵

- Leslie Umberger, “Housewives, Witches, Beauty Queens, and Conjure Women: Locating the Practice of Self-Taught Women Artists,” in Boundary Trouble in American Vanguard Art, 1920–2020, ed. Lynne Cooke (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, 2022), 279–307. ↵

- Raeann Koerner, conversation with the author, March 27, 2023. ↵

- Bottle Village Documents, box 2, Correspondence from Grandma Prisbrey, 1968–1972, Preserve Bottle Village. ↵

- Bottle Village Documents, box 2. ↵

About the Author(s): Elizabeth Driscoll Smith is a PhD candidate in the History of Art & Architecture Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara.