Turning a Corner: Reexamining Joe Jones’s Anthony, Kansas, Mural through Pandemic Eyes

My book project did not begin during the pandemic; its first stage concluded with my dissertation defense in April 2020, still early in the experience of COVID-19 in the United States. For years leading up to my (now virtual) defense, I had been researching and writing about post office murals made under the New Deal’s Section of Fine Arts (the “Section”) and extractive land use in the Great Plains. Toward the end of the dissertation process, the concept of disaster became more important for my project. Today, however, my book project is explicitly framed around the intersection of Section murals and the Dust Bowl; I ask how government-funded public art functioned to shore up (or, occasionally, subvert) both settler colonialism (the root cause of the Dust Bowl) and extractive land use during a period of defined environmental crisis in the 1930s. Across the Plains, muralists turned to history scenes valorizing settlement, idyllic memories of past bountiful harvests, and future-oriented celebrations of the burgeoning oil industry, ostensibly ignoring the dire conditions outside the post office doors.

For me personally, it is difficult to disentangle my work’s shift toward a disaster framing from the pandemic that subsumed life during this time. The seeds of reorganizing the project around the Dust Bowl were sown before the lockdown of March 2020, but the pandemic has changed my perspective on what a community might want from their public art during a disaster: solace and reassurance, for example.1 Through this lens, it was less surprising to me that artists paid through the Section typically did not depict (or even hint at) contemporary disasters in their murals for post offices and courthouses. One exception, the planned eight-mural cycle for Salina, Kansas, by New York artists Harold Black and Isabel Bate, was met with such derision by the locals that the panels were never mounted and eventually disappeared.2 Considering this, I came to wonder, is Section art necessarily a binary, either avoiding disaster entirely or (very rarely) addressing it directly?3 Following this question, my book argues that environmental disaster appears in the seams of Plains post office murals. The development of this argument is rooted in my changed perspective on Missouri artist Joe Jones’s vibrant wheat mural—Turning a Corner, made for Anthony, Kansas—a shift that occurred during the pandemic.

Jones’s mural is something of an anomaly in that it is neither a history scene nor an image of settler-ancestor valorization. Instead, he painted a contemporary wheat harvest with anonymous workers operating modern machinery. On the horizon, however, a dark and confusing cloud form looms (fig. 1). After years of looking, researching, and writing, I began to wonder if this dark cloud contained a more overt reference to disaster. Reviewing the mural and its archive through pandemic eyes, I came to believe that Jones—an artist who cared deeply for the region and its agricultural workers—embedded an intentionally obfuscated citation to a dust cloud in the rain clouds of his mural for the rural Kansas town. In contrast to Black and Bate’s rejected Salina murals, however, Jones’s work succeeded in negotiating the space between avoidance and acknowledgment. While gesturing toward disaster history, the Anthony mural also navigates the local demands for authenticity (a frequent challenge for Section artists) with an orientation toward future prosperity—thereby shoring up a future for the area’s settler agriculture.4

When Jones received the invitation to design a mural for Anthony’s New Deal post office in April of 1939, the southern Kansas town was nearing the end of the so-called Dust Bowl, yet storms and drought persisted in the region, including a particularly brutal storm a month prior.5 Clouds loomed large in the minds of Dust Bowl Americans. Dreams of heavy rain clouds on the horizon kept persistent and hopeful farmers on the Great Plains, while the appearance of dark and rolling dust clouds on the same skyline promised more hours or days of unrelenting, pummeling, airborne dirt. The latter scenario is familiar to art historians through images taken by government photographers like Arthur Rothstein. In a photograph from March 1936 (one of the worst periods of the Dust Bowl), Rothstein captured a looming wall of dirt that seemingly engulfed the entire Texas Panhandle sky, while a lone car appears on the horizon driving toward the camera (fig. 2). The scars of this difficult decade remained. While the Federal Writers’ Project Guide for Kansas (published in 1939, when Jones’s mural was installed) describes the area around Anthony as “a country devoted entirely to grazing and the cultivation of wheat,” it also mentions the frequency of “huge eroded gullies” appearing along the highway.6

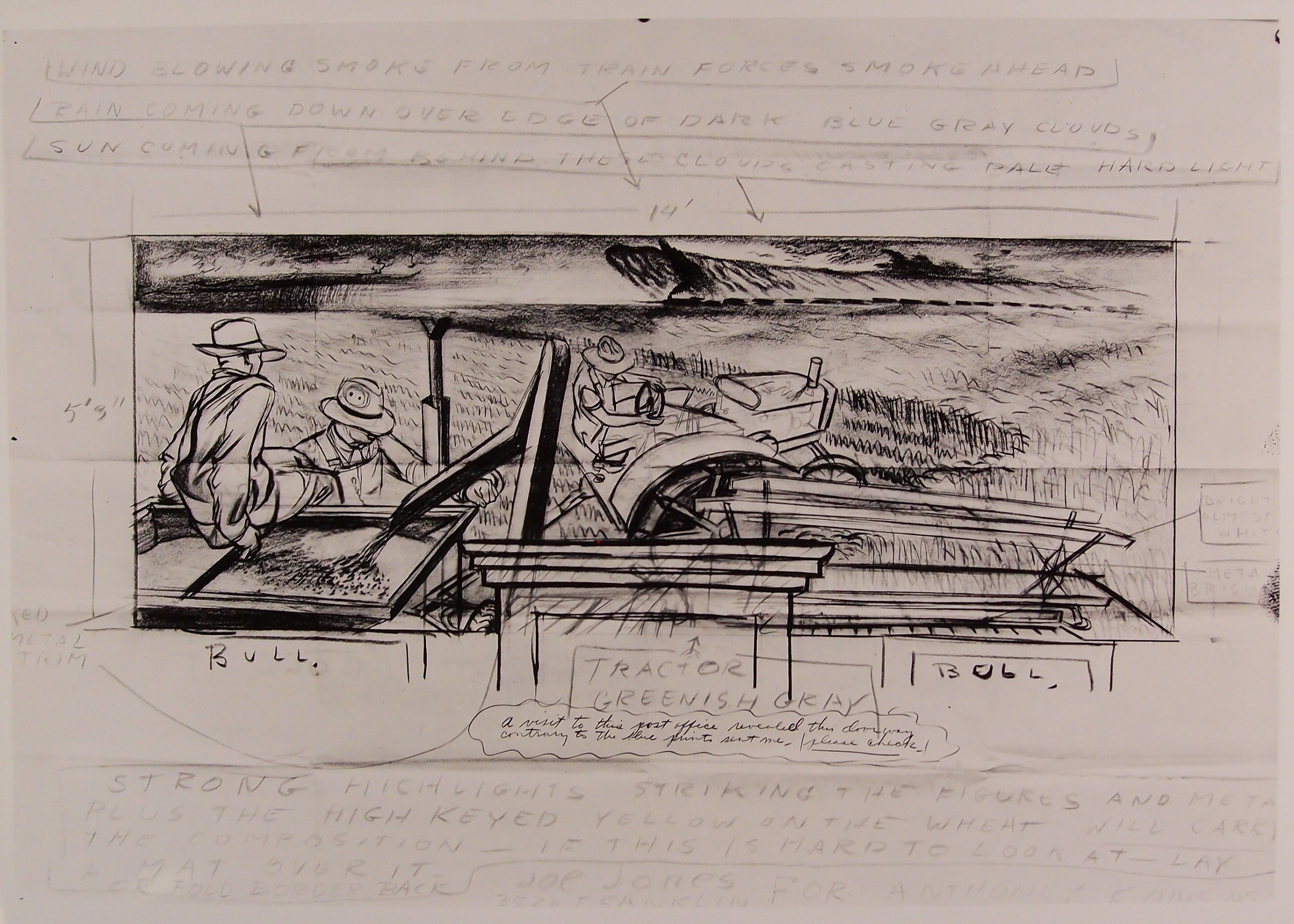

Gullies, however, are absent from the vast wheat fields rendered in Jones’s fourteen-foot mural in Anthony. Instead, rows of recently and soon-to-be harvested soft golden wheat stretch toward the horizon line (and the ominous clouds in question), with a group of three men operating a combine in the immediate foreground. Just above the postmaster’s doorframe, a denim-clad farmer, his face obscured by a white wide-brimmed hat, drives a green tractor pulling the combine, his arms bent and extended in a way that reveals the machinery’s turn toward the uncut wheat in the lower-right corner. An annotated sketch that Jones sent to Section administrator Edward Rowan reveals the care that the artist took in deciding the colors of the green tractor and the red grain tank, as well as the metallic shine of the “almost white” blades; the circle around the two eyelets in the men’s hats demonstrates Jones’s attention to detail (fig. 3).

Jones collected his material in Anthony during the harvest of 1939. An article in the St. Louis Post Dispatch explains that he “lived with the wheat farmers, and climbed up and down their threshing machines with a miniature camera.”7 On-site research was important to Jones, who wrote to Rowan upon receiving the commission to explain that he would delay his trip until July (during harvest season) because “combines are used there and I don’t have enough material on this type of harvesting.”8 This work was evidently successful because, after the mural’s installation in the late summer of 1939, the Anthony postmaster wrote that it was well received and highly regarded by the locals, who could now enjoy a vibrant rendition of the recovered success of their recently beleaguered industry.9 While a wheat mural in rural Kansas might seem like a guaranteed crowd-pleaser, many artists struggled with the local demands of verisimilitude—including Jones. Shortly after completing the Anthony mural, Jones was offered a commission for the northeast Kansas town of Seneca based on another wheat mural that he submitted to a nationwide competition.10 The differences between the two murals and their receptions may demonstrate why the Anthony scene resonated so well with locals.

The Seneca mural study can be read as a different view of the same scene featured in Anthony (fig. 4). Here, the viewer gazes directly at two men dressed similarly to those in the Anthony mural and operating a (possibly identical) tractor and combine. In fact, this vantage more clearly reveals the work of the man turning the wheel on the combine. Once again, these men are engaged in harvesting a vast wheat field, while the unharvested portion rustles in the wind. On the horizon, a farmhouse is just visible beneath a sky heavy with rain clouds. (Notably, these rain clouds are less confusing than the Anthony clouds.) Another combine appears in the middle distance, moving toward the viewer. Ironically, it was likely the technical details that Jones acquired while researching Anthony that doomed the Seneca mural to a controversial start.

After Jones’s planned design was printed in the Seneca newspaper, the town’s postmaster wrote to the artist with concerns brought to him by local residents, who objected to the inclusion of the Massey-Harris brand name on the combine, the apparent age of the machinery, and the erroneous portrayal of their fields as being only full of wheat.11 Though he eventually acquiesced on a few points of criticism by removing the brand name, adding an adjacent cornfield, and removing the machine in the middle ground, Jones resisted altering the age of the machinery. Instead, he argued that the depicted machinery more accurately reflected contemporary Kansas; Jones’s confidence was a direct result of his time spent collecting data and living among farmers in Anthony (research that was validated by the positive reception there).12 On the surface, the Seneca mural faltered with its public because it lacked specific local detail, but Jones also failed to imbue the Seneca painting with the complexity and movement he invested in Turning a Corner.

One of the most important differences between the two murals is where Jones places the viewer in relation to the scene’s action. The Seneca mural positions viewers as distant observers, looking up at a place that they might only partially recognize. In Anthony, however, viewers are situated just behind the machinery amid a familiar wheat field. Standing in the lobby of the Anthony post office, we can look up at the scene and are drawn into the work of harvest, into the moment of the tractor navigating a tricky turn. Each of the three men pictured, with their faces obscured and their bodies pivoted, can serve as a proxy for our viewpoint. Like the depicted men, we can look out to the clouds and the train on the horizon, observe the operating machinery, or glance down toward the unharvested wheat; we have joined them. Contemporary farmworkers would have understood the scene and these actions viscerally. While the Anthony mural is an action scene, the Seneca mural is still, despite likewise depicting a harvest. It holds its viewers at arm’s length. The Anthony mural’s kinetic energy, meanwhile, is further underlined by its title, Turning a Corner. While the title’s verb is vividly rendered by Jones, the phrase is also meant idiomatically to evoke moving beyond a difficult period.13 Jones stresses this meaning further through the intentionally ambiguous cloud scene on the horizon line.

I argue that the ambiguity of Jones’s clouds was born of his 1930s political convictions. By the end of 1933, Jones was a known communist who aimed to use his art as a tool for social change, both through depictions of injustice and community work.14 In St. Louis, he led an interracial group of unemployed students in creating a thirty-seven-foot mural titled Social Unrest in Old St. Louis for the city’s Old Courthouse. Though the class was quickly shuttered due to suspected communist activity, Jones continued to use the mural medium as a means for illuminating oppression and injustice. In 1935, he completed a forty-foot mural for Commonwealth College in Mena, Arkansas, depicting scenes of sharecroppers, environmental disasters (including a dust storm), lynchings, and a miner’s strike.15 Because of Jones’s early convictions, Karal Ann Marling argues that the artist’s post office murals, with their crowd-pleasing scenes of wheat harvests, represent a distancing from his communist politics.16 Jones’s work changes across the decade, but there is no reason to believe that he viewed all Section mural commissions as mere paychecks. As Andrew Hemingway asserts, Jones’s Section work was not devoid of his politics.17 For example, Jones received the Anthony commission as a result of an unsuccessful entry of railroad workers he submitted to a mural competition for the post office in Wellston, Missouri. Responding to Rowan, who questioned the wisdom in Jones’s proletarian subject matter, Jones defended his choice: “I know it’s a better one artistically, socially, and intellectually.”18 Yet, in the same letter, Jones is also enthusiastic about the possibilities for his next commission in Anthony and the program as a whole. This exchange demonstrates that Jones remained optimistic about the social potential (and responsibility) of the mural medium—an important insight into his mindset as he began work on Turning a Corner in Anthony.

The perception that Jones’s two Section murals in Kansas were a rupture from his earlier work results, in part, from the unrelenting bleakness of his Dust Bowl material, which differs from the optimism of his other Section commissions.19 One of his most famous early paintings, American Farm (1936; Whitney Museum of American Art) depicts a lonely cluster of farm structures marooned on a dramatically eroded bluff; sharp gullies radiate from the plateau and stretch across the landscape while the horizon is illuminated by soft light diffused by gray clouds. American Farm was completed after Jones toured areas of drought in the Midwest on special assignment for the Resettlement Administration.20 For six weeks in the summer of 1936, Jones sketched and photographed the ravages of extreme drought. In a note to Elizabeth Green, his friend and benefactor, dated July 23, 1936, Jones explains that the drought drew him further west than originally intended, “the drouth [sic],” he writes, “is a classical development. Nothing has impressed me so much before.”21 Jones illustrated his journey for a St. Louis magazine with images of withering corn, hungry cattle, and a lonely windmill backed by clouds.22

Jones’s Dust Bowl experiences clearly stayed with him, so much so that he successfully applied for a Guggenheim fellowship to document the disaster in 1937. With more financial support and a newly purchased car, Jones was able to immerse himself in the lived experience of Dust Bowl families. Jones’s itinerary is unclear in the archival material, but a note written to Green allows us to imagine at least one of his trips: “Everything going well—I got some good shots today and I have stopped over night on this side of the dust bowl for a rest and a shower. I’m planning tomorrow to go into Colorado and then South into the Panhandle.”23 If we read “this side” to mean the east, as he drove from Missouri, then it is most likely that Jones wrote from Kansas. While it is impossible to trace his exact route, Jones likely traveled through central Kansas (possibly even near Anthony) to the far west of the state and into southeastern Colorado, some of the worst-hit areas of the Dust Bowl, before crossing into the drought-stricken Oklahoma Panhandle.

The work that Jones produced from this period includes reference photographs of dusty roads and paintings of downtrodden farmers in sepia tones. I am most compelled by a 1937 ink drawing titled Dust Storm.24 Dust Storm combines Jones’s forte, wheat threshing, with a menacing dust storm rolling over the horizon. Unlike in the Anthony mural, the farmer in this drawing is alone, harvesting the wheat with a thresher rather than a combine. The evidence of his hard work is visible in the lines of cut wheat and the crop gathered in shocks, but that labor is under immediate threat from the rolling wall of soil. Jones makes great use of his medium, allowing the tendrils of ink to escape the outline of the dirt cloud, giving the storm texture and a vibrant tactility. Dust Storm is a distressing vision of the devastation that Plains farmers lived with throughout the 1930s. So how did Jones go from this piece to a government-sponsored buoyant wheat mural? I argue that, rather than representing a break from socially engaged art, the Anthony mural demonstrates continuity with Jones’s Dust Bowl experience.

The visual evidence for my argument rests with the paired clouds on the horizons of Dust Storm and Turning a Corner in Anthony.25 On a formal level, the storms depicted in the mural and the drawing have a few things in common: their placement on the right side of the horizon, the diagonal slats within the clouds, and the way the farmers are caught midharvest, looking warily at the approaching weather. However, there are certainly differences. The dust storm in the ink drawing is well-defined both in its rendering and through the work’s title, while the storm in the mural is visually confusing. In Anthony, a leaning wall of gray runs alongside red train cars; at points it seems to blend with smoke from the train and the nearly black rain clouds hanging low in the sky (fig. 6). And yet, this form is also distinct from the sky around it and made more prominent by the pointed gaze of the worker seated in the foreground. After receiving a photograph of Jones’s completed mural in August 1939, Rowan wrote to him about the perplexing “dark elements immediately in back of the long train . . . particularly the diagonal projections in the center of the composition.”26 In typical fashion, Jones was dismissive of the critique, but his evasive response and refusal to alter the design demonstrate intentionality behind the storm’s ambiguity.

[It] is smoke from the train driven ahead of the train by a wind travelling at a higher speed. Unusual scenes like this are of course typical only where a lot of sky can be seen at one time—inhabitants of Kansas will understand what’s going on as much as though it were a tornado or any other kind of unusual sky formation. Above the diagonal forms are cloud formations with the sun behind them, color helps here in giving it conviction.27

While Rowan was satisfied by the explanation, Jones’s description leaves lingering questions. The smoke driven ahead of the train explains only the very dark line issuing from the engine (barely visible in reproductions). In the annotated sketch that Jones sent to the Section, a note confirms that the line of dark smoke belongs to the train, but of the “diagonal forms” Jones only notes, “Sun coming from behind these clouds, casting pale hard light.” This vague description of “clouds” contrasts with the more descriptive text annotating the clouds on the left: “Rain coming down over edge of dark blue grey clouds.” The absence of the word “rain” in connection with the “diagonal forms” on the right implies that they may not be rain clouds. Jones echoes this vague terminology in his letter to Rowan, calling them “cloud formations.”

I do not mean to imply that the confusing cloudlike forms on Jones’s horizon secretly represent a dust storm.28 However, I do believe that, in their ambiguity, Jones gives space in the mural for the contemplation of recent disasters. Notably, in his own description of the “unusual” scene, Jones invoked another scourge of Kansas life—tornados. But unlike the Salina muralists, who depicted both tornados and dust storms to local outrage, Jones left room for interpretation of both the clouds on the horizon and their relationship to the figures in the foreground.

For his 1939 audience slowly recovering from the Dust Bowl and the Depression, the cloud formation could represent longed-for rain; it could be a trick of the Plains light amid a distant storm; or it could be a memory of the perilous dust storm.29 Yet even in the worse and final interpretation, Jones includes a message of hope, not only in the opposing rain clouds on the left but in the physical action of the figures and the mural’s title: turning a corner. This reading is bolstered by the inclusion of the train, a symbol of commerce, and the mural’s placement in a post office—the sheer existence of which historically signified permanence for settler communities on the Great Plains. Crucially, if Jones’s clouds do reference a dust storm, the mural does not imply settler responsibility for the disaster (unlike, for example, Alexandre Hogue’s works about the Dust Bowl).30

What does it mean to look for disaster in art? In the early months of COVID-19, Michael Lobel examined the difficulty of seeing the 1918 influenza pandemic in the art of the early twentieth century. He argues that the devastation’s overlap with World War I and the lack of central motifs and monuments made the virus hard to depict and even harder for art historians to apprehend. Lobel suggests finding the 1918 pandemic’s presence in the art world “by looking not for direct references but rather to analogies, transpositions, and displacements.”31 Ultimately, Lobel finds the pandemic best expressed in John Singer Sargent’s Gassed, a work also intended for a public building. While the Dust Bowl does not suffer from the same lack of visibility as a virus, I similarly wonder if the lingering traumas of the Dust Bowl may be best captured in Jones’s enigmatic clouds. I write this piece during our third year of COVID, and, for me, it remains difficult not to see the pandemic everywhere. Spring 2020 fundamentally transformed my research. My project, partially spurred by rethinking Turning a Corner, is now an effort deeply shaped by a pandemic—a transformation that raises as many methodological questions as it answers. From this shifted vantage point, I posit that the success of Turning a Corner lies in its vagueness, in pairing visions of a more bountiful future with dark clouds on the horizon, allowing viewers to acknowledge that those clouds recently held dangerous dirt, not healing rain. At the same time, the rain clouds on the left portend a different future, a turning away from that traumatic past.

Cite this article: Michaela Rife, “Turning a Corner: Reexamining Joe Jones’s Anthony, Kansas, Mural through Pandemic Eyes,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15079.

Notes

- Before COVID, for example, I largely dismissed Birger Sandzen’s Section murals in Kansas as little more than pleasant landscapes. Amid the early months of the pandemic, letters sent to the Section to request Sandzen’s work, like a 1939 letter from Kansan Clara May Hawes, now read differently to me: “Dr. Sandzen is very popular in this part of the State for he manages to see beauty in our scenery—and to be able to make us see it too.” Clara May Hawes to Edward Rowan, September 18, 1939, box 34 (Case Files Concerning Embellishments of Public Buildings, 1934–1943), entry 133, Records of the Public Buildings Service, record group 121, National Archives II, College Park, Maryland. ↵

- For more on the Salina controversy, see Karal Ann Marling, Wall-to-Wall America: Post Office Murals in the Great Depression (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982), 232–49. ↵

- In Wall-to-Wall America, Marling writes that “the missing center of New Deal cultural history—the calamitous present—is not portrayed on the post-office wall” (Wall-to-Wall America, 21). Andrew Hemingway also details the lengths that Section leadership went to in order to keep murals benign and pleasant. But, much as I argue for environmental disaster, Hemingway suggests that leftist artists (including Jones) used their Section murals to subtly communicate their labor politics; see Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002), 153–56. ↵

- Alyosha Goldstein argues that settler colonialism, as a condition, is “remade at particular moments of conflict”; see his “Where the Nation Takes Place: Proprietary Regimes, Antistatism, and U.S. Settler Colonialism,” South Atlantic Quarterly 107, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 835. I contend that the Dust Bowl, precipitated by irresponsible settler farming that destroyed crucial native grasses, was such a moment. Amid the apparent demise of the American agrarian fantasy, government-sponsored artworks (like Jones’s mural) functioned to shore up settler faith in an enduring industrial agriculture. ↵

- Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 34. ↵

- Kansas: A Guide to the Sunflower State, Federal Writers’ Project of the WPA (New York: Viking, 1939), 430. The following page also offers a description of the area akin to Jones’s mural: “West of Harper fields of wheat, from 500 to 4,000 acres in extent, flank the highway. In the smaller fields binders cut and bind the wheat. The bundles are fed to a huge threshing machine which pours the grain into sacks while the straw is blown out like smoke. In the larger fields combines cut and thresh the grain in a single operation.” ↵

- “Joe Jones Completes His Seventh Mural,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, undated clipping, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- Jones to Rowan, May 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. Jones also sent Rowan photographs of combines at work from his visit to Anthony; Jones to Rowan, June 23, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- Anthony Postmaster to Rowan, September 15, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- The Section’s “48 States Competition” in 1939 allowed artists to submit a mural design for a small post office in one of the (then) forty-eight states. Jones expressed his enthusiasm about submitting in a letter to Rowan that accompanied his Anthony sketch—further connecting the two murals. Jones to Rowan, July 3, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- W. L. Kauffman to Jones, November 18, 1939, box 34, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- Jones to Rowan, December 4, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. Despite the rocky start, Senecans ultimately praised Jones’s revised mural—in no small part because of the changes and the interventions of their postmaster, as a local newspaper article stated: “It may be said that the painting is in part the work of Senecans”; see “Postal Mural Here; It’s Nice,” undated newspaper clipping, box 34, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- In early examinations of the mural, I suspected that Jones incorporated the doorframe into his painting, making it the obstacle that the farmers were navigating around. However, both his sketch and letters to Rowan demonstrate that he was unprepared for the interjecting doorframe and that he simply cut out part of the planned machinery. ↵

- For example, Jones found early success on the East Coast with his haunting antilynching painting American Justice (1933), now at the Columbus Museum of Art. ↵

- For more on Jones’s political convictions and explicitly social justice–themed work, including the Old Courthouse and Mena murals, see M. Melissa Wolfe, “Joe Jones, Worker-Artist,” in Joe Jones: Radical Painter of the American Scene, ed. Andrew Walker (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2010), 33–53. For a larger discussion of American artists and communism, see Hemingway, Artists on the Left, chap. 1–2, including discussion of the Section of Fine Arts. ↵

- Karal Ann Marling, “Joe Jones: Regionalist, Communist, Capitalist,” Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 4 (Spring 1987): 54. While Wolfe also discusses an apparent shift in Jones’s style, she attributes the change to his increased connection with other “socially aware artists,” his brief employment by the Resettlement Administration, and his more permanent relocation to New York. Wolfe, “Joe Jones, Worker-Artist,” 48–49. ↵

- Hemingway, Artists on the Left, 153–56. ↵

- The committee for the St. Louis–area competition selected an allegorical design with robed figures and a dove. The Section, however, insisted on a historical scene of a stagecoach on the St. Louis waterfront by Lumen Winter. Jones was blunt with Rowan, writing “between you and me, I ask you what is more obtuse—trite and generally unrelated to the lives of people living in St. Louis (which is Wellston) than a covered wagon and smug southern gentleman.” Jones to Rowan, April 17, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- Jones completed five murals for the Section of Fine Arts, all of which were harvest scenes; see Andew Walker and Janeen Turk, “Joe Treasury Department Murals,” in Joe Jones: Radical Painter of the American Scene, ed. Andrew Walker (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2010), 117–21. ↵

- As Andrew Walker points out, Jones’s painting bears a resemblance to Walker Evans’s 1936 photograph Erosion near Jackson, Mississippi; see Andrew Walker, “Joe Jones and the Dust Bowl: A Search for Social Significance,” in Joe Jones: Radical Painter of the American Scene, ed. Andrew Walker (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2010), 67. ↵

- Based on a telegram to Green, Jones made it at least as far west as Mitchell, South Dakota. Joe Jones to Elizabeth Green, telegram, July 22, 1936, Dr. John Green Collection, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis (hereinafter Green Papers). His quote about the drought comes from a letter the following day: Jones to Green, July 23, 1936, Green Papers. ↵

- “The Drouth as Seen by Joe Jones,” East St. Louis Journal (Illinois Magazine), September 6, 1936. ↵

- Jones to Green, undated postcard, c. April 1937, Green Papers. Walker also notes that Jones’s itinerary is unclear. For a more extensive look at Jones’s relationship to the Dust Bowl, see Walker, “Joe Jones and the Dust Bowl,” 55–79. ↵

- Dust Storm is currently in a private collection but a reproduction can be found on page 168 of the Saint Louis Art Museum’s 2010 exhibition catalogue, Joe Jones: Radical Painter of the American Scene, ed. Andrew Walker (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2010), 168. ↵

- It is important to underline that Jones’s interest in the Dust Bowl clearly extended beyond his trip. In December 1937, he applied (unsuccessfully) for an extension of his Guggenheim fellowship to continue work in the region. ↵

- Rowan to Jones, August 8, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- Jones to Rowan, August 12, 1939, box 32, 121/133, National Archives II. ↵

- I am not alone in reading a deeper meaning into Jones’s wheat paintings. Writing of Threshing No. 1 in 1935, poet Archibald MacLeish asked viewers to “examine more thoughtfully the face of the farmer with his left fist in yours {a probably deliberate paraphrase of the communist salute} which brings the whole landscape into line” (Archibald MacLeish, “U.S. Art: 1935,” Fortune, December 1935, 69). ↵

- Dust Bowl–era media analogized dust storms to forms of weather. For example, a Life magazine feature on the Dust Bowl compared the encroaching dirt to both fog and “low thunderheads” (“March of Time Cameramen Catch a Dust Storm Rolling over Texas Panhandle from Oklahoma,” Life, June 21, 1937, 63). ↵

- On Hogue, see Mark Andrew White, “Alexandre Hogue’s Passion: Ecology and Agribusiness in The Crucified Land,” in A Keener Perception: Ecocritical Studies in American Art History, ed. Alan C. Braddock and Christoph Irmscher (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2009), 168–88. ↵

- Michael Lobel, “Close Contact,” Artforum, April 21, 2020, https://www.artforum.com/slant/michael-lobel-on-art-and-the-1918-flu-pandemic-82772. ↵

About the Author(s): Michaela Rife is an assistant professor and postdoctoral scholar at the University of Michigan.