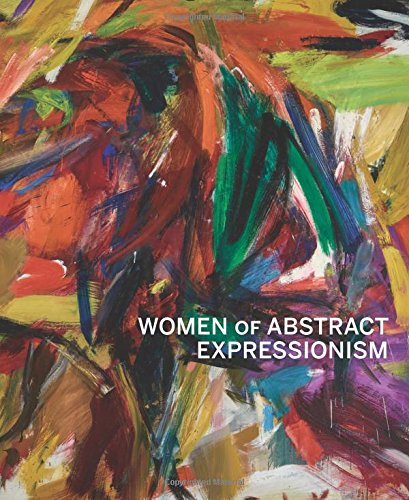

Women of Abstract Expressionism

Edited by Joan Marter

Introduction by Gwen F. Chanzit; essays by Robert Hobbs, Ellen G. Landau, Susan Landauer, and Joan Marter; and an interview with Irving Sandler

New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Denver Art Museum, 2016; 216 pp.; 138 color and 50 b/w illus.; ISBN: 9780300208429; $65.00

Exhibition schedule: Denver Art Museum, Colorado, June 12–September 25, 2016; Mint Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina, October 22, 2016–January 22, 2017; Palm Springs Art Museum, California, February 18–May 28, 2017

Studying historical women artists requires an understanding of both the blatant sexism that kept women from fully participating in the art world and the way the existing scholarship of an era diminishes or ignores the achievements women artists managed to accomplish. Women of Abstract Expressionism, the lavishly illustrated compendium accompanying the 2016 Denver Art Museum exhibition of the same name, deftly balances these two priorities. The book, edited by Joan Marter, includes an introduction by exhibition curator Gwen F. Chanzit as well as essays by Marter and other noted Abstract Expressionism scholars, Ellen G. Landau, Susan Landauer, Robert Hobbs. An interview with Irving Sandler by Marter, a chronology of women’s participation in the movement by Jesse Laird Ortega, and biographies of forty-two artists by Aliza Edelman complete the volume. Although it builds upon key resources, such as Ann Eden Gibson’s Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics and Marter’s 1997 Women and Abstract Expressionism exhibition at the Sidney Mishkin Gallery at Baruch College, Women of Abstract Expressionism is the first exhibition at a major museum with the singular purpose of exploring the contributions women artists made to Abstract Expressionism in America. In her introduction to the catalogue, Chanzit explains the specific goals for this project: to broaden the history of Abstract Expressionism so that it includes women artists as key progenitors of the style and to expand the definition so that it incorporates those creative practices in which women artists specialized. The works illustrated here are “painterly expressions brought on through direct or remembered experience.” (14) They are creative responses to nature, place, personal history, social history, politics, literature, music, dance, and religion. They are varied, vivid, and “liberating” at a time when, as Chanzit notes, “a canvas might be the sole platform for a woman’s autonomy.” (10)

Studying historical women artists requires an understanding of both the blatant sexism that kept women from fully participating in the art world and the way the existing scholarship of an era diminishes or ignores the achievements women artists managed to accomplish. Women of Abstract Expressionism, the lavishly illustrated compendium accompanying the 2016 Denver Art Museum exhibition of the same name, deftly balances these two priorities. The book, edited by Joan Marter, includes an introduction by exhibition curator Gwen F. Chanzit as well as essays by Marter and other noted Abstract Expressionism scholars, Ellen G. Landau, Susan Landauer, Robert Hobbs. An interview with Irving Sandler by Marter, a chronology of women’s participation in the movement by Jesse Laird Ortega, and biographies of forty-two artists by Aliza Edelman complete the volume. Although it builds upon key resources, such as Ann Eden Gibson’s Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics and Marter’s 1997 Women and Abstract Expressionism exhibition at the Sidney Mishkin Gallery at Baruch College, Women of Abstract Expressionism is the first exhibition at a major museum with the singular purpose of exploring the contributions women artists made to Abstract Expressionism in America. In her introduction to the catalogue, Chanzit explains the specific goals for this project: to broaden the history of Abstract Expressionism so that it includes women artists as key progenitors of the style and to expand the definition so that it incorporates those creative practices in which women artists specialized. The works illustrated here are “painterly expressions brought on through direct or remembered experience.” (14) They are creative responses to nature, place, personal history, social history, politics, literature, music, dance, and religion. They are varied, vivid, and “liberating” at a time when, as Chanzit notes, “a canvas might be the sole platform for a woman’s autonomy.” (10)

Twelve artists were represented in the galleries of the Denver Art Museum. However, more than forty are discussed in the catalogue, ranging from relatively familiar names, such as Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning who worked in and around New York City, to lesser-known painters, such as Bernice Bing and Claire Falkenstein who worked in the San Francisco Bay Area. Narrowing the representation in the museum exhibition to the primary twelve must have been difficult, and no clear criteria are outlined regarding how those artists were selected, other than that they represent two distinct geographical loci of Abstract Expressionism and that they “stand in for the many who worked within the late 1940s and 1950s art world.” (11) Presumably, an equally compelling show of another twelve painters could be mounted elsewhere in the future, and the research contained in this catalogue would provide a helpful starting point to the curator who picks up the baton and carries on. Chanzit mentions that in the course of the preparation of this project over one hundred artists were considered, and while “most were not consistent participants in the movement” and do not belong in this particular study, the very existence of such a long roster of potential candidates indicates that this generation of women artists is ripe for reconsideration. (11)

Joan Marter’s essay, “Missing in Action: Abstract Expressionist Women,” is an excellent starting point as it enumerates some of the many obstacles faced by women in this movement. From sexism among the male artists drinking at the Cedar Bar to the insulting nature of Clement Greenberg’s assessment of art by women as decorative and overly polished, women were embattled by literal and rhetorical boys’ clubs. Women artists were rarely represented by dealers, galleries, or solo shows as their careers were developing, and even when they were, those contributions were overlooked by early historians of Abstract Expressionism. Marter also charts the few exhibition opportunities that were open to women abstractionists in the 1950s including the Ninth Street Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture in 1951 and the annual exhibitions at the Stable Gallery from 1953 to 1957. These early displays featured work by men and women—paintings by Grace Hartigan and Helen Frankenthaler hung alongside those by Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, and others—and the selection committee included Perle Fine, Joan Mitchell, and Elaine de Kooning. These shows offered exposure and leadership opportunities for women artists. They provide evidence of women’s participation as makers and curators in the Abstract Expressionist movement from an early moment, which makes the neglect that such women have suffered ever since all the more egregious.

The case studies of Fine, Anne Ryan, and Michael (Corinne) West that Marter includes in her essay reinforce the frustrations that women, who were as ambitious and as creative as their male counterparts, faced as they tried to gain recognition. Early on, in 1947, critic Jean Franklin praised Fine’s work, writing of her paintings’ “emotional and ideological impact” and that “the meaning of her pictures cannot even be approximated in words.” (22) But in 1978, when Fine wrote to the Whitney Museum twice to demand that she be counted among the pioneers in their Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years exhibition, not only was she not included, but her correspondence went unanswered. Unfortunately, this anecdote is not unique to Fine. Such disrespect seems to be the rule rather than the exception, but Marter concludes her chapter with the reminder that “the canon of Abstract Expressionism can be reconstituted to include these women.” (28) What might it be like to teach a survey of art history and, instead of rehearsing the traditional examples of Pollock as a gestural painter and Mark Rothko as a Color Field artist, use Krasner and Fine as the primary examples of the style?

In “‘Biographies and Bodies’: Self and Other in Portraits by Elaine and Bill de Kooning,” Ellen Landau considers the disparate contributions to figuration by this wife and husband. Beginning with a prescient analysis of a Hans Namuth photograph of the de Koonings and one of Krasner and Pollock in which the women are passive witnesses to the men’s creativity, Landau examines the unique partnership that the de Koonings maintained during the 1940s and 1950s as they used themselves and each other as models. Landau counters the thesis of the Namuth photograph by offering examples of Elaine’s ability to depict her powerful self and to sketch her husband as the eroticized subject of her gaze. Landau also analyzes the narrative and stylistic tensions in Bill’s images of women and couples, which may reflect his feelings about the fraught nature of his marriage to Elaine. It seems that, for better or worse, the relationship between Elaine and Bill played out in the studies, sketches, and paintings they made of themselves and each other. Paradoxically, although both artists are known for figurative work, Elaine is remembered as a portraitist, and Bill is not. Bill always saw the practice of depicting another person as an act of self-expression, while Elaine “always strove to put herself in their shoes.” (37) Elaine’s portraits were empathic, Landau argues, and that trait has not been typically associated with Abstract Expressionism.

Susan Landauer’s “The Advantages of Obscurity: Women Abstract Expressionists in San Francisco” is remarkable for its assertion that in the Bay Area, women artists did not suffer from significant gender-based discrimination and that they, like their male counterparts, ironically benefited from the relative paucity of galleries and patronage for contemporary art on the West Coast. That benefit came in the form of artistic freedom: painters like Jay DeFeo, Ruth Armer, and Claire Falkenstein labored according to their own creative impulses, unhindered by the pressures of or competition for commercial success. The California School of Fine Arts (now known as the San Francisco Art Institute) acted as an experimental laboratory where students and teachers, women and men, developed a unique Post-Surrealist, postwar, anti-decorative mode of art-making that is reflected in diverse work by such artists as Lilly Fenichel, Emiko Nakano, and Berenice Bing. Landauer masterfully analyzes the formal strengths of paintings by these artists and her essay destabilizes the sexism at the core of this project and the geographical bias against artists working outside of New York and its environs.

In his essay, Robert Hobbs applies the notion of metonymy to the work of Krasner, Mitchell, and Frankenthaler. His goal is to demonstrate how these artists infused their paintings with poetic meaning that diverges from, but is no less sophisticated than, the metaphoric paintings of male Abstract Expressionists. Whereas Pollock and others spoke of their work as nature, energy, and performance, Hobbs argues that Krasner, Mitchell, and Frankenthaler’s paintings intuitively represent the tensions between self, nature, and creativity. One example of this is Krasner’s Listen (1957; Private Collection), which incorporates her signature as a prime compositional element that visually relates to forms that resemble breasts and leaves. Hobbs cites this as an example of the loose alliance of symbols that suggest Krasner’s evolving emotions, which, despite the vibrant colors of the painting, she remembered as sorrowful as she embarked on a career after Pollock’s death and explored her own autonomous creative voice. In Mitchell’s case, metonymy involves an empathetic response to nature that led her to use memories of taking her dog to a swimming hole as the impetus for the nonrepresentational, but allusive and expressionistic George Went Swimming at Barnes Hole, but It Got Too Cold (1957; Albright-Knox Art Gallery). Hobbs does not analyze a specific work by Frankenthaler, but examines the way paintings she made after Mountains and Sea (1952; National Gallery of Art) mobilize lyricism to evoke places or sensations that can be both fleeting and universal. Hobbs’s conclusion, that these artists’ paintings should be understood “as contingent views of each of these women’s own nature, which is partially and indistinctly witnessed through its connections with the physical world as it is being poetically invoked through the process of painting,” is precisely the kind of redefinition of Abstract Expressionism that Chanzit promised in her introduction. (65)

Joan Marter’s 2013 interview with Irving Sandler corroborates some of the information presented elsewhere in this book. He remembers Frankenthaler, Hartigan, and Mitchell as “really strong painters,” but stubbornly upholds the supremacy of Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Rothko and the separation between first- and second-generation painters, which has pushed so many women to the margins. This interview illustrates the difficulty of reorienting the entrenched, biased histories of the movement. But it is followed by fifty-one color plates of paintings of such vibrancy and expressive force, by artists such as Mary Abbott, Sonia Gechtoff, Deborah Remington, and Ethel Schwabacher, that the necessity of doing so is inescapable. The chronology and biography sections offer further evidence of the achievements of women, and the photographs of women artists at work are particularly resonant. Seeing Ruth Abrams leaning over a cluttered table of supplies; Janice Biala and Alma Thomas putting brush to canvas; Buffie Johnson with her gargantuan Astor Theatre mural; and Mercedes Matter teaching a class at the New York Studio School (which she founded) enlivens the stories of their artistic trajectories told here.

The words overdue, egregious, and biased pepper Women of Abstract Expressionism, and this review, because they so aptly describe the inexcusable obliteration of women’s histories heretofore. With few exceptions, since the 1950s, scholars and critics have rooted American Abstract Expressionism in the signature styles and macho personas of artists such as Pollock and Willem de Kooning and the intense, iconic spiritual concerns of Barnett Newman and Rothko. Discussions of women artists have often felt like side notes if they are present at all. Women of Abstract Expressionism is a necessary chronicle of the biographies, styles, and reception of significant artists whose careers deserve greater attention. It is, like the exhibition that inspired it, a motivational resource for researchers, educators, and enthusiasts of mid-twentieth century American art. It should inspire any reader to look askance at the traditional narratives of this era and encourage art historians to incorporate the women artists chronicled here in their scholarship and teaching.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1593

PDF: Kuykendall – Women of Abstract Expressionism

About the Author(s): Lara Kuykendall is Assistant Professor of Art History at Ball State University.