“I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building”: Words FDR Never Said

PDF: Cherny, Things FDR Never Said

In 1998, US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor prepared the opinion of the court in the case of National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley. She was joined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices John Paul Stevens, Anthony M. Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a separate concurring opinion, which Justice Clarence Thomas joined. Justice David Souter wrote a dissent. At issue was a 1990 amendment to the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act. That act created the two national endowments, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The 1990 amendment, enacted after complaints about some NEA grants, required the NEA to take into “consideration general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public.”1 In response, the NEA created a review panel to ensure that proposals met those objectives. Karen Finley, whose proposal had been rejected by the review panel, joined by three other artists whose proposals had also been rejected and the National Association of Artists’ Organizations, challenged the review proceedings as being unconstitutionally vague and discriminatory. The complainants prevailed in the initial court decision and in the appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court. However, when the NEA appealed to the Supreme Court, that body upheld the 1990 amendment, thereby confirming that the federal government is allowed to discriminate when allocating funding. Justice O’Connor drafted the opinion.2

In her opinion, Justice O’Connor’s fifth footnote reads:

On proposing the Public Works Art [sic]Project (PWAP), the New Deal program that hired artists to decorate public buildings, President Roosevelt allegedly remarked: ‘I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building.’ Quoted in Mankin, Federal Arts Patronage in the New Deal, in America’s Commitment to Culture: Government and the Arts 77 (K. Mulcahy & M. Wyszomirski eds. 1995). He [i.e., Roosevelt] was buying, and was free to take his choice.

Justice O’Connor’s source for Roosevelt’s statement was Lawrence D. Mankin’s chapter in the anthology America’s Commitment to Culture: Government and the Arts.

Fortunately for Justice O’Connor, her decision did not hinge on this quotation. Like others over the past sixty years, she relied on a secondary source for the Roosevelt quotation rather than confirming it by going to the original source. Other authors have provided a longer version of Roosevelt’s alleged words, citing the quotation as coming from George Biddle’s autobiography: “You talked of Rivera and ‘social ideals’ and ‘the Mexican Revolution.’ You stuck out your neck. I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building. They all think you’re communists.”3 Authors have repeatedly interpreted these words as Roosevelt’s reaction to Biddle’s letter of May 9, 1933, which has long been cited as the origin of the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP, which lasted from mid-December 1933 to late April 1934). The PWAP was the first New Deal art project and the prototype for the three subsequent New Deal arts projects. Most importantly, the authors who present the quotation all interpret it as a warning from Roosevelt to avoid controversial content in federally funded art. However, Roosevelt never said those words, and everyone who has quoted him has apparently misread or misunderstood a comment by Biddle—not Roosevelt.

So where and how did the confusion arise? We may begin with Mankin’s “Federal Arts Patronage in the New Deal,” upon which Justice O’Connor relied, which gives the following citation for the quote:

Steven Dubin, Bureaucratizing the Muse (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), pp. 10–11. Dubin cites the quote from Gerald Monroe, The Artists Union of New York (Ed.D. diss. New York University, 1971).

So we can see that Justice O’Connor (or her law clerk) cited a secondary source, which cited a secondary source, which cited a secondary source. A sampling from other authors who have presented the false quotation yields similar results. Some offer no citation. Others cite a secondary source. A few do cite Biddle’s autobiography but, curiously, fail to understand it. A selection of examples will illustrate the problem; I present them all purposefully without citation, as my intention here is not to embarrass anyone. A first example, from 1966:

Although the President later replied that “I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building” (a jibe at the controversial Diego Rivera portrait of Lenin in the artist’s later-destroyed Rockefeller Center mural), the first Federal art project got under way in December 1933 [given without citation].

A second example, from 1970:

Franklin D. Roosevelt, commenting on the suggestion that the federal government should undertake a relief program for unemployed artists, expressed some misgiving: he didn’t want, he told a friend in 1933, “a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building” [given without citation].

A third example, from 1986:

When the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP, forerunner of the WPA) was being discussed in 1933, President Roosevelt’s response to its major proponent set the mood of caution with which such programs were generally undertaken: “I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building” (quoted in Monroe, 10–11). By referring to the radical political motifs included in the work of popular Mexican muralists, from the beginning national leaders decided that the output of government-supported art projects would have to be monitored [citing Monroe, the same source Mankin gave].

And, finally, a fourth example, from 2017:

“There is a matter which I have long considered and which some day might interest your administration,” Biddle wrote to Roosevelt in May 1933, explaining how the Mexican muralists worked at “plumbers’ wages” to “express on the walls of government buildings the social ideals of the Mexican revolution,” and how he imagined that the young artists of America too could “[express] in living monuments the social ideals that you are struggling to achieve.” Roosevelt was into the idea and supported Biddle, but Biddle’s proposal was initially rejected by the national Fine Arts Commission, who were understandably weary [sic] of setting a bunch of lefty artists loose on government buildings. Roosevelt, in turn, subtly encouraged Biddle to persevere with the effort in one of the more badass presidential memos I’ve ever seen: “You talked of Rivera and ‘social ideals’ and the ‘Mexican Revolution.’ You stuck your neck out. I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building. They all think you’re communists. Remember my position. Please. I wash my hands. But here’s the dirt. Now it’s up to you.” [citing a 1982 dissertation].

It is high time to clear this up once and for all. Biddle’s 1939 autobiography, An American Artist’s Story, provides the full context for understanding the quotation in question. He first gives an account of his May 9, 1933, letter to Roosevelt encouraging federal support for artists and citing the example of the Mexican muralists, a letter often quoted in accounts of the creation of the PWAP. These accounts also indicate that Roosevelt put Biddle in touch with L. W. Robert Jr., in the Treasury Department, who brought in Edward Bruce, also in the Treasury Department, and that those officials took the lead in creating the PWAP late in 1933.4

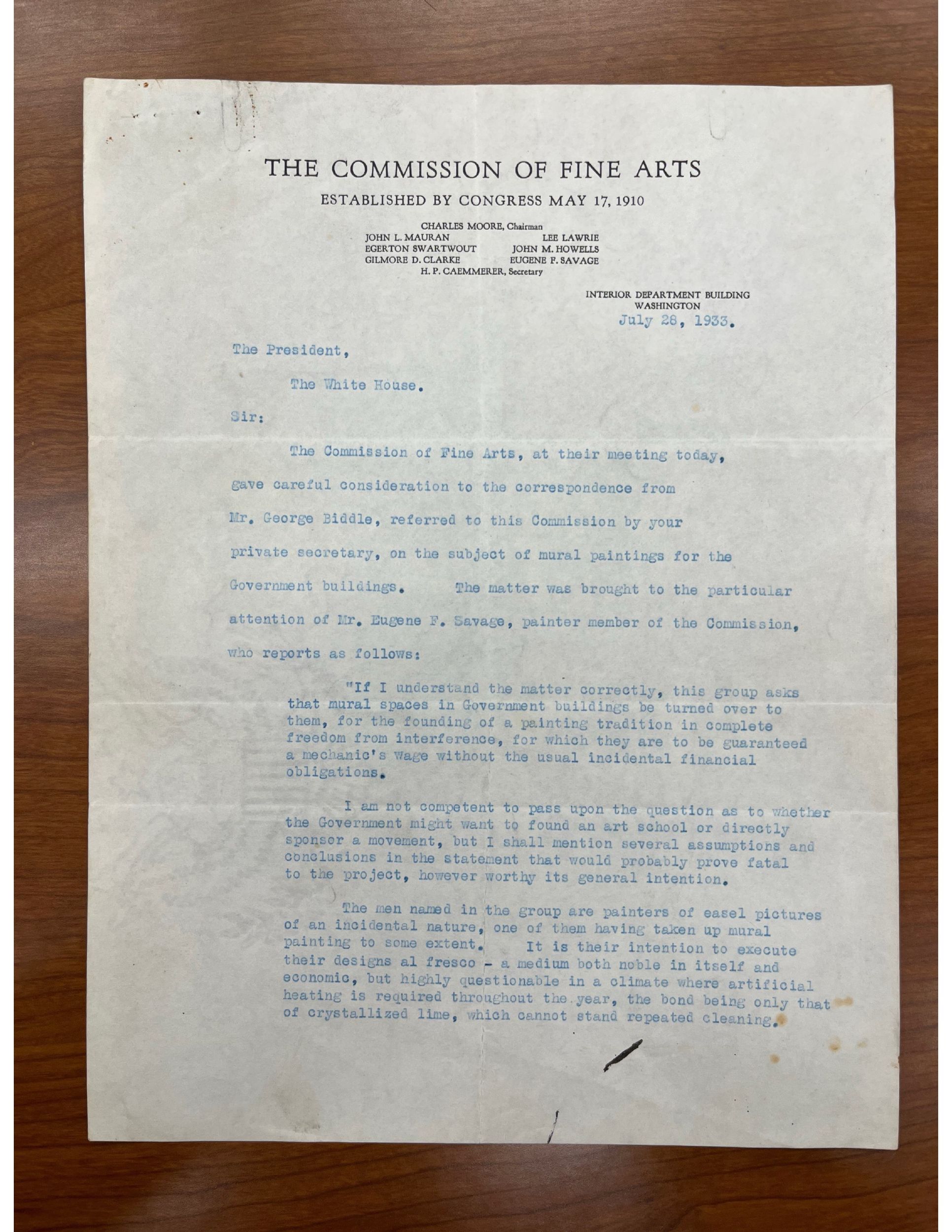

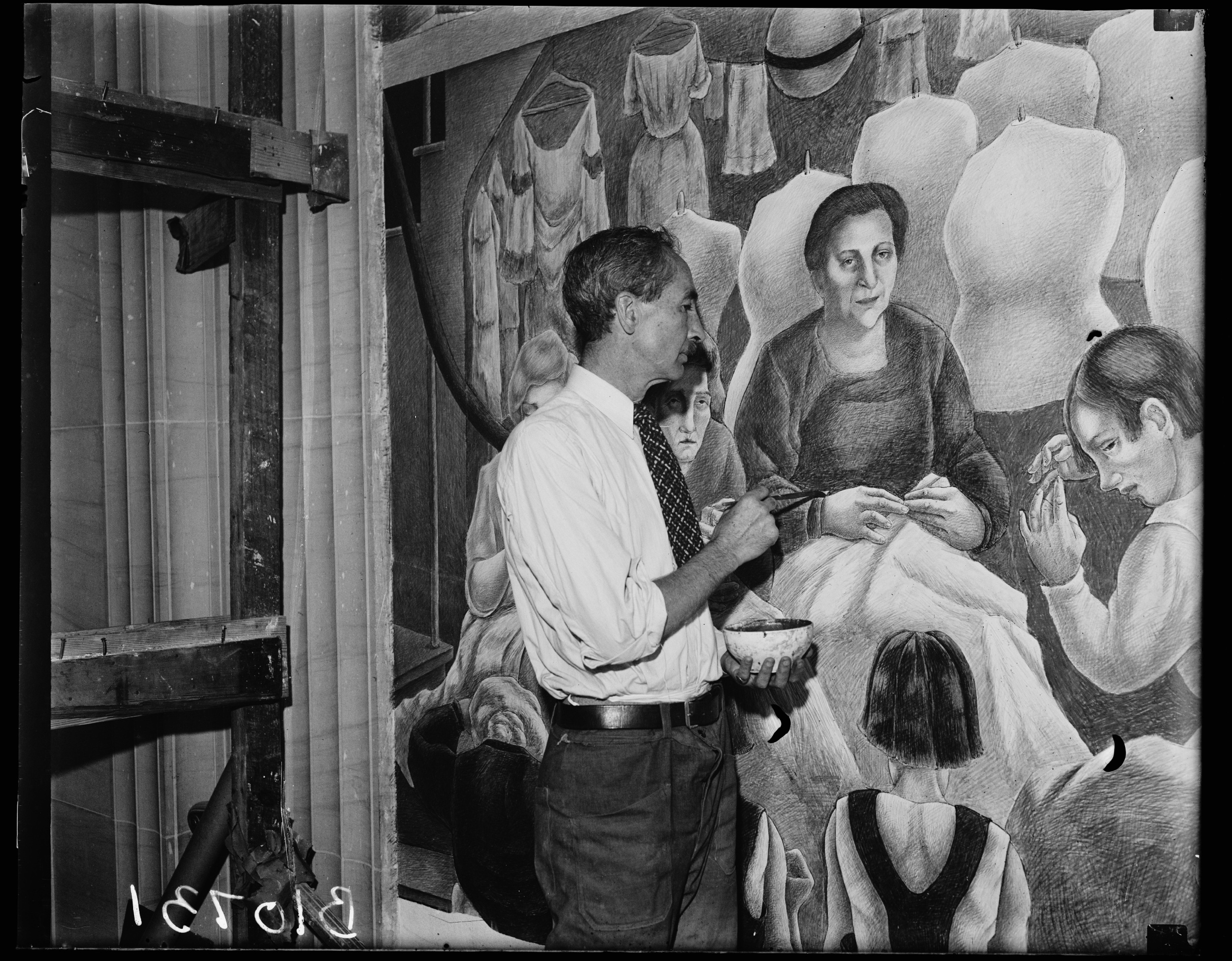

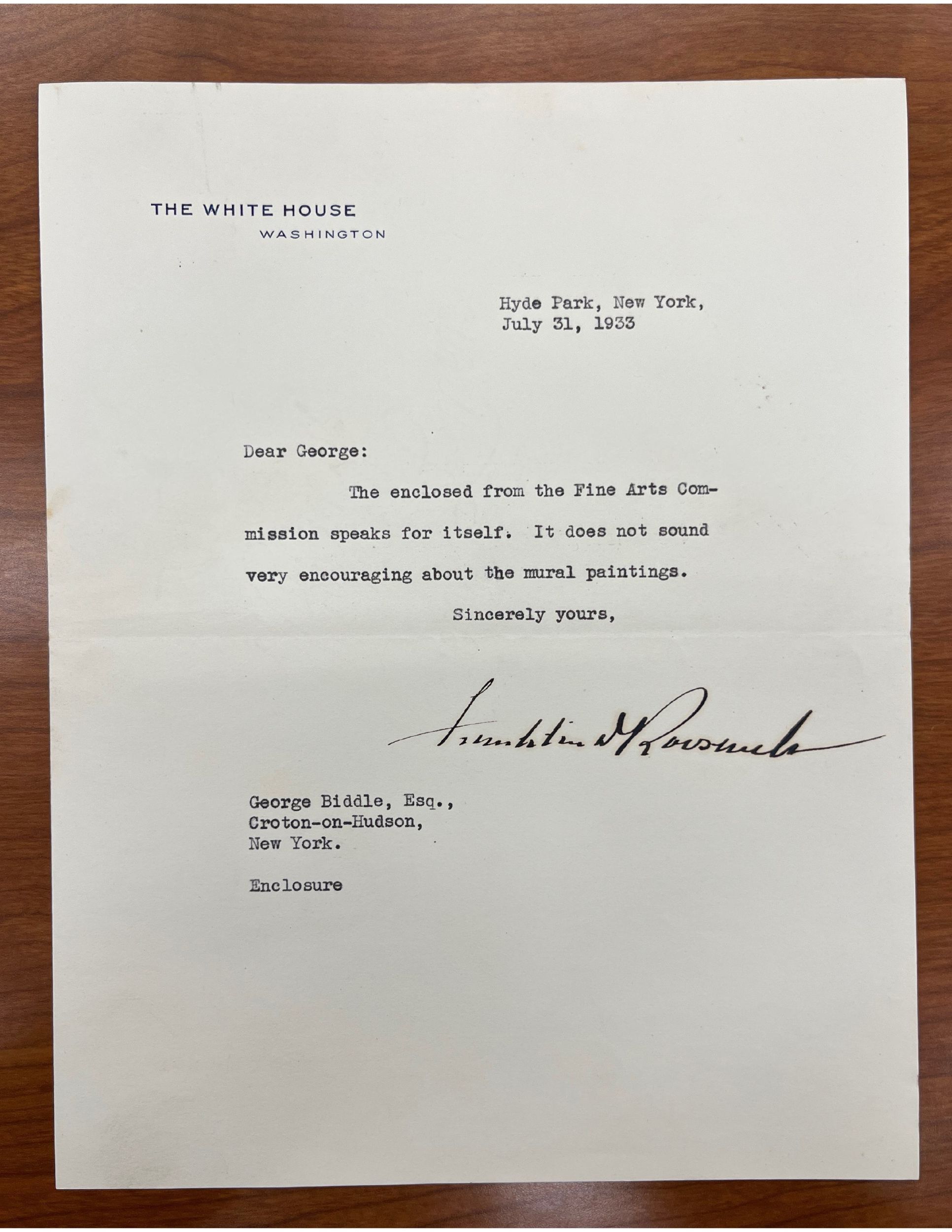

In his autobiography, Biddle then recounts that, in mid-1933, several weeks after that first letter, he sent Roosevelt another letter, proposing a specific mural project, including certain artists, for the Justice Department building. Roosevelt sent this second proposal from Biddle to the federal Fine Arts Commission for review and comment. That agency returned a negative review. According to Biddle’s memoirs, on August 6, 1933, Roosevelt sent the commission’s review to Biddle with a short cover memo that said only: “The enclosed from the Fine Arts Commission speaks for itself. It does not sound very encouraging for the mural painting” (fig. 1a).5

In his memoirs, written some five years after the events occurred, Biddle provides this account of the Fine Arts Commission’s review of his proposal for the Justice Building:

They had arrived upon reflection at “several assumptions and conclusions” that would “probably prove fatal to the project.” Our group were “painters of easel pictures of an incidental nature”; our intention ignored the architect. “The efforts at mural painting by some of the group and others of their persuasion” had “been attended by much controversy and embarrassment,” “condemned by the profession for chaotic composition, inharmonious in style and scale with the building and in subject matter, professing a general faith which the general public does not share. I think the government would be glad to avoid such experiences.” Our group also ignored “the established tradition built up by its pioneers and fostered by the American Academy at Rome—which has brought forth a younger, more liberally minded and murally trained modern talent.”6

Biddle provides the following characterization of Roosevelt’s short cover memo:

What the President might have done was to file the report and so clear his desk of one more routine correspondence. But he had written a letter, which I believed I might thus translate: Dear George: You talked of Rivera and “social ideals” and “the Mexican revolution.” You stuck out your neck. I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building. They all think you’re communists. Remember my position. Please. I wash my hands. But here’s the dirt. Now it’s up to you.7

Biddle’s memoirs make clear that these words are not Roosevelt’s language but his own interpretation (he called it a translation) of Roosevelt’s very brief memo, which was included when he forwarded the Fine Arts Commission’s review of Biddle’s proposal for the Justice Department building. Although the first “translated” sentence seems to point to Biddle’s letter of May 9, 1933, which did refer to Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and the Mexican muralists, the discussion of “Lenin’s head” can only be understood as a reference to the events from mid-1933 through February 1934, when Rivera included a portrait of Lenin in his mural Man at the Crossroads for New York’s Rockefeller Center (fig. 2). News of Rivera’s work in progress appeared in mid-May 1933. Nelson Rockefeller, who was in charge of the project, stopped work on the mural, eventually paid Rivera his commission, and, during the night of February 9, 1934, had his workers destroy the mural. The event received nationwide press coverage.8 Biddle’s mention of “communists” may also refer to the nationwide press coverage of another controversy in July and August 1934, when an artist painted a hammer and sickle as part of a PWAP project at Coit Tower in San Francisco.9

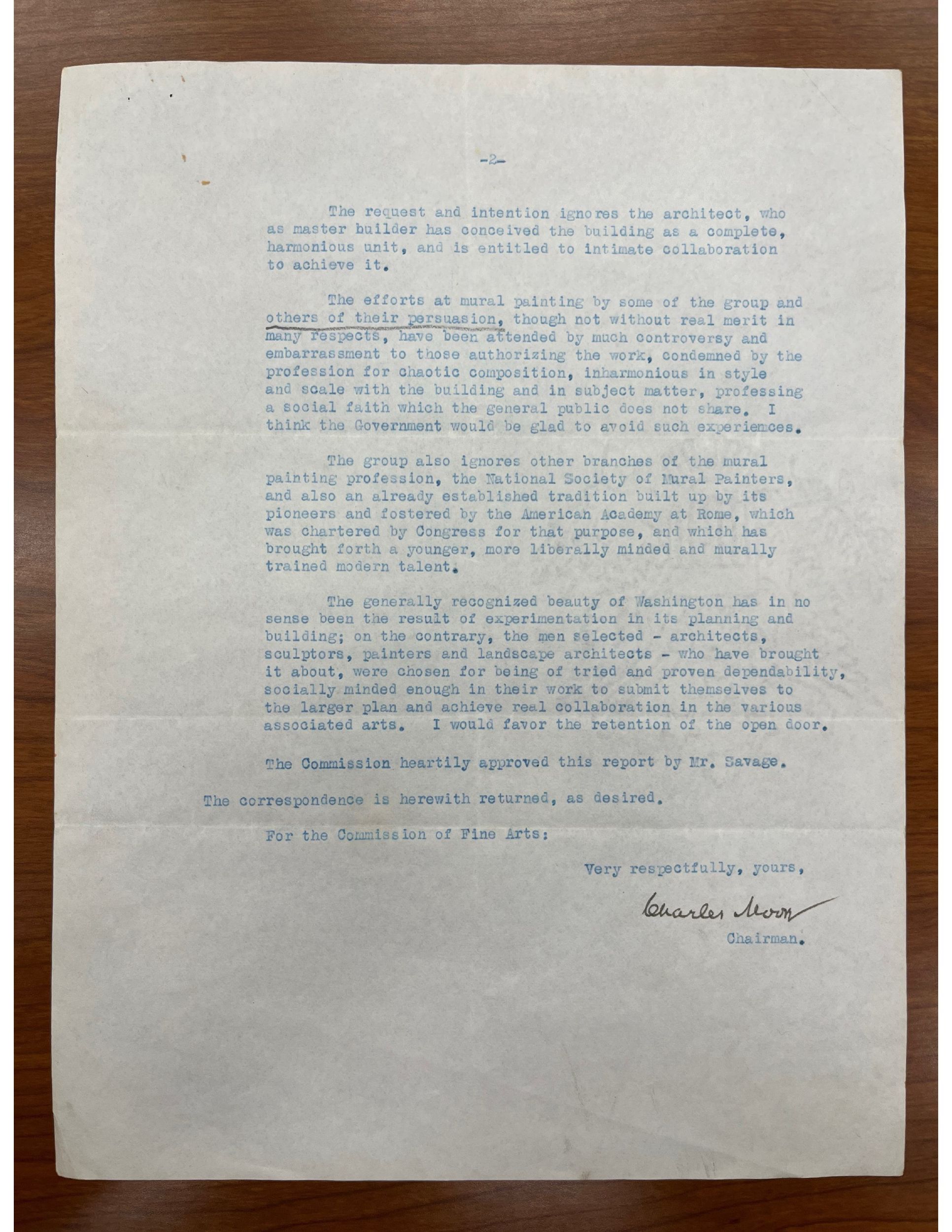

The remainder of this section of Biddle’s autobiography discusses and presents photos of his own work on the Justice Department murals in 1936 (fig. 3).10 It fails to mention PWAP by name or even by implication, and it focuses on Edward Bruce’s administration of the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture (1934–42), renamed the Section of Fine Arts in 1938 and usually called “the Section.” Biddle also stresses the difference between the Section and the Fine Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration.

A review of Biddle’s papers at the Library of Congress provides several corrections to the version he presents in his memoirs. The finding aid to the Biddle papers lists box 30 as the location of communications from Roosevelt in 1933–43. There is only one item in box 30, file 5: “General Corr-FDR,” a letter dated July 31, 1933, and postmarked at Poughkeepsie on August 1, 1933 (see fig. 1a–c). Roosevelt’s very short cover letter consists only of the two sentences quoted by Biddle: “The enclosed from the Fine Arts Commission speaks for itself. It does not sound very encouraging for the mural painting.” The enclosure is a two-page letter from Charles Moore, chairman of the Commission on Fine Arts, dated July 26, 1933. Most of that letter quotes a member of the commission, Eugene F. Savage. Savage’s analysis contains some of the phrases quoted by Biddle in his memoirs but not always in the same context. The phrase “several assumptions and conclusions in the statement that might prove fatal to the project” is clearly a reference to Biddle’s proposal for the Justice Department. Savage raises questions about the suitability of fresco as a medium for buildings requiring artificial heat. Savage also states: “The efforts at mural painting by some of the group and others of their persuasion [Biddle underlined the last four words in pencil], though not without real merit in many respects, have been attended by much controversy and embarrassment to those authorizing the work, condemned by the profession for chaotic composition, inharmonious in style and scale with the building and in subject matter, professing a social faith which the general public does not share.” Savage’s reference to the American Academy in Rome is mostly the same as Biddle reported. As is plain to see, neither Roosevelt’s cover letter nor the detailed analysis provided by the commission contains any reference to Rivera, Lenin’s head, or communists, although “a social faith which the general public does not share” was almost certainly a reference to the Left.

What is clear, both from Biddle’s autobiography and the original documents, is that Roosevelt never said, “You talked of Rivera and ‘social ideals’ and ‘the Mexican Revolution.’ You stuck out your neck. I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building. They all think you’re communists.” These words are Biddle’s “translation” of Roosevelt’s memo. However, they have repeatedly appeared in the work of art historians over the past sixty-plus years, always attributed to Roosevelt, not to Biddle, and usually presented as evidence that the president expected federal art to avoid political content. Those accounts routinely (as seen in the examples I provide) conflate Biddle’s two separate proposals (first, for what later became the PWAP; second, for murals in the Justice Department building) and present Biddle’s “translation” of Roosevelt’s comments about his second proposal as a reference to his first proposal.

For future researchers, the most important message to take away from this investigation is to not trust another author’s quotation but always to go to the primary source for confirmation.

Editors’ Note: Read more about more recent projects that were inspired by the history of the WPA in the Colloquium section of this issue.

Cite this article: Robert W. Cherny, ““I can’t have a lot of young enthusiasts painting Lenin’s head on the Justice Building”: Words FDR Never Said,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 2 (Fall 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.20441.

Notes

- Public Law 101-512, 101st Congress, Sec. 103, (b). ↵

- National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley, 524 U.S. 569 (1998). For the full opinion, see https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/524/569/#. For a discussion of the case, see “National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley,” Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1997/97-371. ↵

- George Biddle, An American Artist’s Story (Little, Brown, 1939), 273. ↵

- See, e.g., Lenore Clark, Forbes Watson: Independent Revolutionary (Kent State University Press, 2001), 104–9; and Richard D. McKinzie, The New Deal for Artists (Princeton University Press, 1973), chaps. 3–11. The creation of the PWAP is also presented in “WPA Art Collection,” US Department of the Treasury, accessed August 23, 2025, https://home.treasury.gov/about/history/collection/paintings/wpa-art-collection. ↵

- Biddle, American Artist’s Story, 269–72. ↵

- Biddle, American Artist’s Story, 273. ↵

- Biddle, American Artist’s Story, 273. ↵

- For the initial press coverage, see New York Times, May 19, 1933, 1. See also Diego Rivera, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (1960; Dover, 1991), 124–29; and John Lear, “Diego Rivera Paints the Proletariat,” in Diego Rivera’s America, ed. James Olos (University of California Press, 1922), 168–69. ↵

- Robert W. Cherny, The Coit Tower Murals: New Deal Art and Political Controversy in San Francisco (University of Illinois Press, 2024), chap. 4. ↵

- Biddle, An American Artist’s Story, 273–83. The available photos of Biddle with his mural at the Department of Justice building seem to be posed for two reasons. First, fresco artists work from the top down (as seen, e.g., in Cherny, The Coit Tower Murals, 15–16, figs. 2.1–.2), and Biddle’s photos show him with paintbrush in hand, posed above the completed mural. Second, mural artists typically do not work in a white shirt and tie while applying pigment to wet plaster. ↵

About the Author(s): Robert W. Cherny is professor emeritus of history at San Francisco State University.