Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation

Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate

Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021

Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713)

It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability. This changed as Basquiat’s star rose and monographic treatments, more suited for hagiography and auction sales, added this young Black artist to the pantheon of modern masters.2 Four years after his death in 1988, Black feminist theorist bell hooks reflected on the limits of such exhibitions. “Basquiat’s work holds no warm welcome for those who approach it with a narrow Eurocentric gaze,” she wrote, “which can only recognize Basquiat if he is in the company of . . . highly visible white figure[s].”3 Efforts to see artists from the margins within their cultural contexts have reinvigorated art history over the last quarter century, and a host of recent exhibitions—including The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2015), We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 (Brooklyn Museum, 2017), Art after Stonewall: 1969–1989 (Columbus Museum of Art, 2020), and Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (MoMA PS1, 2021)—have chronicled art-making outside of traditional art schools, markets, and histories. Like these other efforts, Writing the Future investigates collective practices and aesthetic innovation writ large to better appreciate the power and politics of artistic production in the United States.

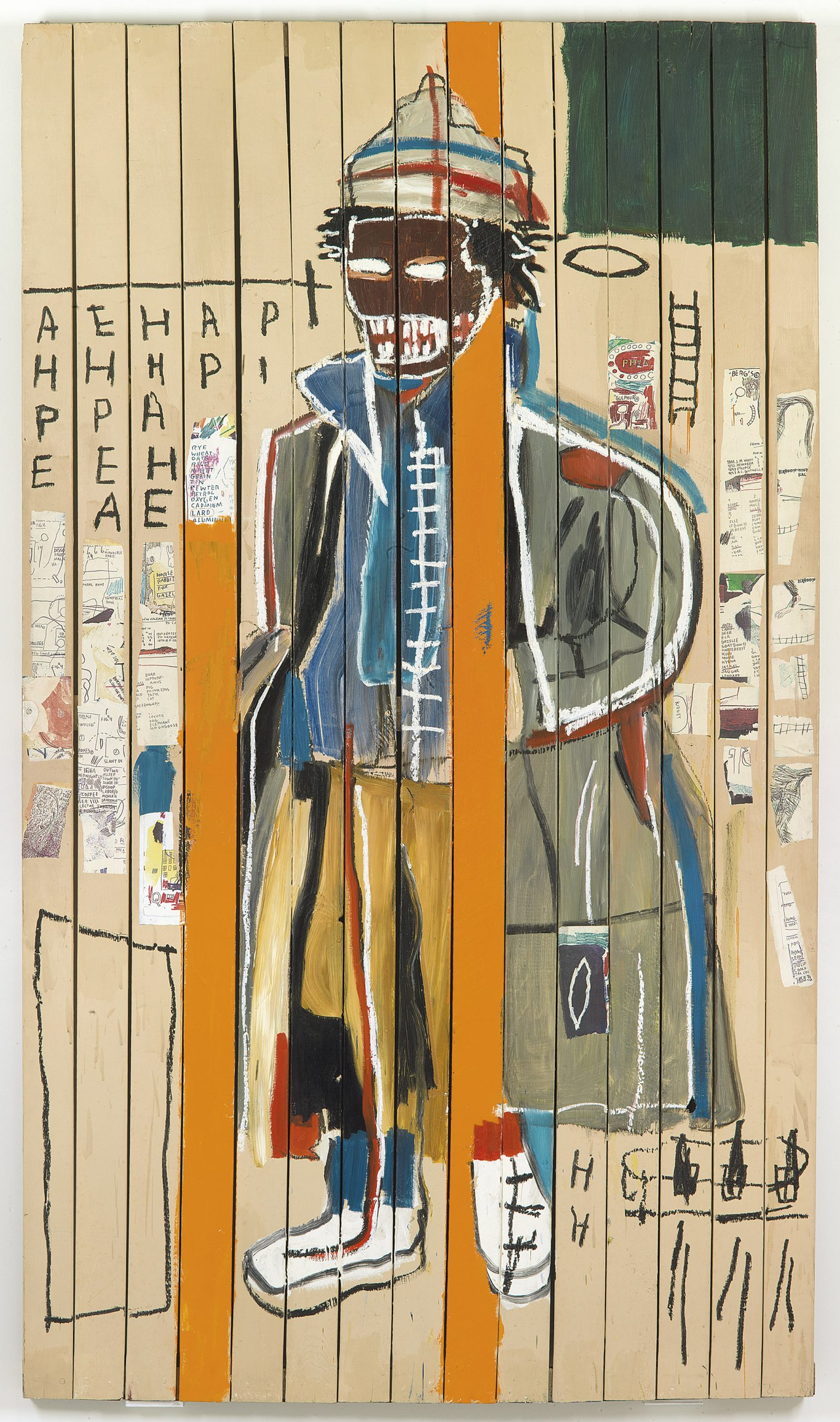

Writing the Future celebrates friendship and loss; dance, art, music, and poetry; and Black life from the ancient world to the future. The tour starts at the refrigerator with Untitled (Fun Fridge) (1982; fig. 1), tagged by nearly every artist in the exhibition, and Lee Quiñones’s Fab 5 (1979; Collection of KAWS), with its title in spray paint on canvas honoring musician, artist, producer, actor, and guiding light of the scene Fred Braithwaite (b. 1959; known as Fab 5 Freddy). A leather jacket tagged by Basquiat and friends hangs in the corner near a refrigerator door painted over by Futura (b. 1955; then called Futura 2000), televised interviews with graffiti notables, and one large Basquiat painting, Untitled (1983; Private collection) with “Soap Box” written across it. It is as if our host is expounding on the topics in the painting: oil, cattle, sugar, labor, and art, while friends come and go. This is the post-graffiti moment when street art created by young Black artists of New York was recognized as capable of transforming visual culture from nightclubs to art museums. Once out of the kitchen, Basquiat takes over the introductions with a room of portraits in his most characteristic style: expressive figuration and roughly covered surfaces punctuated by handwritten text and quickly rendered pictographic signs. Hollywood Africans (1983; Whitney Museum of American Art), featuring Basquiat, Toxic (b. 1965), and Rammellzee (1960–2010) in Los Angeles, accompanies full-length portraits Ero (1984; Private collection) and Anthony Clarke (1985; fig. 2), the subject of which was known as A-One (1964–2001). These images of young artists find an uneasy companion in Six Crimee (1982; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), a six-by-twelve-foot field of blue and white supporting the heads of six Black men, with halos suspended above them and scratched signs of urban architecture below. The only unidentified portraits in the room, these postmortem images insert themes of criminalization, incarceration, and death, threatening the communities of color from which graffiti arose.

The heart of the exhibition celebrates and educates on the four pillars of hip-hop: graffiti, MCing (rapping), DJing, and breaking (dancing), and sometimes also a fifth—fashion. Vitrines with books passed between Lady Pink (b. 1964), Ero (1967–2011), and Zephyr (b. 1961) showed these graffiti artists’ collaborative processes and morphological invention while contrasting with Basquiat’s more private sketchbooks. The project of developing graffiti styles for the art world fell to others, notably Futura, whose tagged signature and atmospheric fields enlist spray-painted, spattered, stenciled, and scraped effects to create complex spatial relationships that dematerialize the canvas, wall, or anything on which they appear. One striking inclusion was a suite of album covers that Futura designed for five acts, including his own, on the New York City Rap Tour, the first European hip-hop concert tour. When aligned, the records create a five-foot spacescape united by Futura’s gestural line and anchored by a bright white “2000.” Blondie’s “Rapture” (1981), the song that marked pop music’s embrace of rap, echoed throughout the room. The video, projected many times larger than the television screens that originally hosted it, includes cameos by Basquiat, Braithwaite (also featured in the lyrics), and Quiñones. Smaller screens played performance footage of Madonna onstage in a leather skirt suit that was painted by Keith Haring (1958–1990) and LA-2 (b. 1967), and another with Rammellzee rapping. The only solo work by Haring, Untitled (Boombox) (1984; Collection of Larry Warsh) appears in the back corner of the gallery.

Since the early 1980s, Haring was the artist most often paired with Basquiat, demonstrating what Braithwaite called the “coming together among races that was really unique in New York, at that time” and presenting this young community as better able to embrace difference than the wider worlds outside it.4 Adjusting the myth of this dynamic duo to the reality of the relationship and to a thesis emphasizing the cultural power of hip-hop and graffiti as outgrowths of the Black American experience is a vital and complex historical project. Haring’s presence in the exhibition, along with occasional references in ephemera and object labels to the range of supporters—artistic, critical, and financial—from outside the Black community hints at the challenge of presenting Black artistic production, as hooks suggests, in relation to the Black histories that nurtured it, while historicizing artists’ encounters with difference. Basquiat was explicitly and perhaps ambivalently concerned with, and uniquely successful at, engaging the white art world that would remain largely indifferent to his Black peers. Rammellzee, by contrast, defied structures of white support, while others landed on different positions. At the exit to the portrait room, a marker-on-plate portrait of Haring with three penises, one in hand and two in flight, raises unaddressed questions of how difference was encountered within the artistic community. Lady Pink appears in this context as significant for her work—from tags, cityscapes, and conceptual collaborations with Jenny Holzer (b. 1950)—but also for being the lone woman of color in the show. As hip-hop has become a site for powerful expressions of gender and sexuality in twenty-first-century global culture, there is tremendous value in examining how its artists encountered difference at its inception. Likewise, the art-historical record as well as our current moment benefits from spotlighting Black cultural production.

Once out of the New York nightclubs, we are thrust in the path of a twenty-four-foot manifesto of Gothic Futurism, with works by Rammellzee, the underground hero of the movement: Hell, the Finance Field Wars, unfinished studies in second dimension, first six panels, merging of Decoyism (Back-up unit) 6-delig (1979) and Evolution of the World (1972/1982). The drawings detail a transportation hub through which graffiti tags confront robots and incoming fire. On a station wall is a list of this world’s protagonists: “Bomber$ Gangster$ Wizzard$ Assassin$GRAFF:DJ:MC: BREAK(ER$(.” An adjacent drawing explains: “You will read the law! You will hear the thunder BUT only a ‘Wizzard’ can ‘read’ ‘read’ the ‘Lightning.’” We are witnessing graffiti aesthetics used to “weaponize, militarize . . . historicize and futurize” language.5 This typographical transformation was not a metaphor. It was resistance by other means: “You think war is always shooting and beating everybody up, but no, we had the letters fight for us.”6

Up to this point, Rammellzee, who died in 2010, had been a minor player in the exhibition. As the mood turned from materialist to futurist, however, his combination of lived experience, quantum physics, world history, aesthetics, and passion became central. Supplementing Hell and Evolution is a typed draft of his “Iconic Treatise Gothic Futurism Assassin Knowledges of the Remanipulated Square Point * One to 720 Rammellzee % Ramm X Ell = Zee ∞” (1979; Collection of Vincent Vasblom), which argues for accelerating the evolution of font design to align the creation and communication of meaning within disempowered communities. Rooted in the development of writing in the Roman and Gothic periods, contemporary re-manipulation can be seen in graffiti styles from Bomberism to Wild Stylism to Rammellzee’s Ikonoklast Panzerism, as each devoted increasing attention to contour and condensation of the abstract and the real. Panzerism was suited for conflict and essential for the “build procedure” that would construct a Gothic Future. “To wipe out a language and make a new one is hard work,” Rammellzee explained.7 This prophesized future can be gleaned from the relics on display: modified watches called Timestoppers, clothing, music, and Panzerist panels by Rammellzee, Kool Koor (b. 1963), and Toxic.

Basquiat is missing from the Gothic Future but returns to reembody the exhibition with stripped-down white-on-black anatomical studies, labeled in handwriting more childlike than weaponized. These studies, based on Henry Gray’s book, Gray’s Anatomy (1858), contrast with three flamboyant spray-painted works by Lady Pink: a nude female torso and two monumental collaborations with Holzer; one is a blooming orchid, while the other features skulls inspired by Susan Meiselas’s photo book Nicaragua.8 Holding together these signs and scenes of flesh and bone is Brain (1985; Collection of Sandra and Gerald S. Fineberg), twenty-seven stacked wooden boxes on which Basquiat collaged and painted notes, photocopies, and sketches of now-familiar themes: record albums, names and events, organs, and body parts. Atop the pile is a bootblack stand that, together with the boxes, references labor that had been largely and/or historically undertaken by Black men in New York City.

While body and mind serve work, medicine, and war in the penultimate room, the exhibition ends in a cloud of black walls, black lights, cosmic reverence, and life beyond death. Overseeing this astronomical and spiritual apotheosis is a seven-foot robotic Panzerist samurai, Gash-O-Lear (1989; fig. 3). Prepared to do battle with guitars, chains, plastic spears, and model rockets, Rammellzee’s warrior assures safe passage to the beyond. During his lifetime, the artist would don this costume and enact its future, envisioned for us here through paintings by Basquiat, Braithwaite, and Futura. Framing the exit are two funerary objects: Untitled (Black Graffiti Vase) (1983; Collection of Larry Warsh) by Haring and LA2, and a mirrored pyramid Rammellzee built to hold his ashes. Basquiat’s Famous Moon King (1984; Private collection) rises to the drama of Gash-O-Lear but resists the spirit of leave-taking captured in the title of this final gallery: Ascension. Like Brain, this painting is pasted over with photocopies of drawings and overlaid with oil stick, emphasizing the materiality of Basquiat’s practice and his imagery. References from the geography of the West Coast to the Middle East; anatomy from the nervous system to the hand; technology from airplanes to spaceships; and history from Ancient Greece to Colonial America cover the work.

Basquiat just will not leave this world, and with the hip-hop scene that supported him, the work he left behind assertively, enthusiastically, and aesthetically creates a culture that is responsive to history, community, and daily life.

Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870.

PDF: Kalb, review of Writing the Future

Notes

- Rene Ricard, “The Radiant Child,” Artforum 20, no. 4 (December 1981): 36. ↵

- See Suzi Gablik, “Report from New York The Graffiti Question, Art in America 70 (October 1982): 33–39; Nicolas A Moufarrege, “The Year After,” Flash Art 118 (Summer 1984): 51–55; Walter Robinson and Carlo McCormick, “Slouching toward Avenue D,” Art in America 72, no. 6 (Summer 1984): 134–61; and Janet Kardon, Carlo McCormick, and Irving Sandler, The East Village Scene, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art and the University of Pennsylvania, 1984. ↵

- bell hooks, “Altars of Sacrifice: Re-membering Basquiat,” Art in America 81, no. 6 (June 1993): 70. ↵

- Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020), 38. ↵

- Munsell and Tate, Writing the Future, 175. ↵

- Munsell and Tate, Writing the Future, 175. ↵

- Dave Tompkins, “Period Piece: Rammellzee and the End,” Paris Review (April 18, 2012), https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2012/04/18/period-piece-rammellzee-and-the-end. ↵

- Susan Meiselas, Nicaragua (New York: Aperture, 1981). ↵

About the Author(s): Peter R. Kalb is the Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art in the Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University