Confederate Monuments: Southern Heritage or Southern Art?

The future of Confederate monuments in the American memorial landscape is uncertain. Since the Charleston church shooting in June 2015, there have been increasing calls to remove all symbols of Confederate memory from American public spaces. Confederate monuments have been bodily hauled to the ground in acts of iconoclasm, tagged with graffiti connecting them with the Black Lives Matter movement, removed or relocated through legal channels, and recontextualized with text linking them with the history of racial injustice in America. At the same time, Confederate heritage organizations have defended the monuments as key symbols of Southern history and have lobbied to protect them from alteration through legal means. Many state legislatures have passed laws protecting the monuments from alteration, but these laws are also facing legal challenges on constitutional grounds. Public debate has centered on what to do with the monuments: whether to keep them up or take them down, and whether amending them with additional text or art might mitigate their power. But this essay will center on a different set of questions: what role do these monuments play in the field of Southern art? How do they contribute to a regional artistic identity, and how should their position as Southern artworks affect their future fate? In seeking an answer, this essay will explore the conditions under which the monuments were manufactured, their claims of Southern heritage, and their relationship with other forms of Southern public art. Ultimately, it is clear that these works do not represent the lived experience of all Southerners, and that there may be other types of work by Southern artists that would better represent the region.

In order to understand the status of Confederate monuments within Southern art, it is necessary to consider their origins. In the wake of the American Civil War, which cost the lives of an estimated 750,000 soldiers, including both Union and Confederate fatalities, and caused untold damage to civilian lives and property, communities across the nation began to erect monuments to the conflict. In the North, this process began almost immediately, with monuments honoring both the rank and file soldiers and the war’s military and political leaders. But in the South, memorialization proceeded more slowly. The region had been decimated by war, and communities put their scant resources toward rebuilding lost infrastructure rather than erecting expensive monuments. And in the first years after the end of the war, honoring the Confederacy with triumphal monuments was politically risky as former rebels looked to regain their public status within a reunified nation. With political concerns in mind, most memorializing efforts were carried out by Ladies’ Memorial Associations, groups of elite women who organized the reburial of the Confederate dead in special cemeteries and commissioned modest monuments in their honor. But with the end of Reconstruction, as white Northerners gave up on reinforcing respect for the Union and civil rights for all, Confederate monuments grew more numerous and more elaborate. The majority of these monuments were erected between about 1890 and 1920, one of the darkest periods for race relations in the South.1

Most Confederate monuments were not manufactured by Southern artists. Due to the lack of an established public sculpture tradition or the necessary industrial infrastructure to produce fine art statuary, Southern monument committees had to look outside the region for sources of sculpture. Many soldier statues were manufactured by Italian carvers who churned out Confederate statues in white marble. Others were the products of large Northern firms, such as the Monumental Bronze Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut, that sold their replicated soldiers in trade catalogues. In many cases, statues sourced outside the region were placed on bases carved out of local stone and marketed by local firms: the Muldoon Monument Company of Lexington, Kentucky, and the McNeel Marble Works of Marietta, Georgia, were both successful with this model (fig. 1). In iconography, Confederate statues also borrowed from their Northern counterparts: like Union monuments, most Confederate statues feature soldiers standing at some form of parade rest. And in costume, they tended either to be indistinguishable from their Union counterparts—wearing a long overcoat and a kepi—or conforming to the type popularized by the Monumental Bronze Company, with a short shell jacket and slouch hat (fig. 2). In form and manufacture, these statues reflect both the national and international nature of the postbellum memorial landscape.2

One of the few Confederate soldier monuments to be carved entirely in the South in the nineteenth century met with a humiliating end. The Elbert County Confederate Monument, the work of German-American carver Peter Arthur Beiter, was unveiled in 1898 in Elberton, Georgia, to immediate and intense criticism. Born in Ohio to German immigrant parents in 1867, Beiter traveled southward sometime in the 1890s and was involved in carving the base for another Confederate statue in Cuthbert, Georgia, before receiving what was likely his first commission for a full-length statue in Elberton.3 But the resulting monument was a disaster: locals hated its ponderous form, Yankee overcoat, and unsettling, startled expression, and they gave it the nickname “Dutchy” as a nod to its German ancestry. On August 13, 1900, a mob attacked the statue in the middle of the night and brought it to the ground, breaking it into several pieces. The next day, the townspeople buried it where it lay, facedown as a traitor to the Confederacy. In the 1980s, the statue was exhumed, and it now lies on its back on a gurney at the Elberton Granite Museum, enshrined as one of the first products of the town’s successful granite industry (fig. 3). It has been replaced in the town square by one of the mass-produced statues of the Monumental Bronze Company—an embarrassment of local manufacture exchanged for a sleek Yankee interloper.4

Many of the South’s most iconic monuments to military and political leaders of the Confederacy were also manufactured outside the region. A major equestrian monument was an expensive investment, and the first examples did not appear until well after the end of Reconstruction. Two of the most discussed monuments to Robert E. Lee, located in Richmond and Charlottesville, Virginia, are both at the center of highly contested public debates on whether they should remain in the public eye. Richmond’s monument was sculpted by Antonin Mercié after an intense artistic competition, and was cast in Paris under his direction (fig. 4). The committee chosen to judge the competition consisted of architect Edward Clark and sculptors John Quincy Adams Ward and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, all Northerners and highly respected professionals. The Richmond Lee Monument was the first to be placed on the storied Monument Avenue, which became one of the key Southern examples of the City Beautiful Movement.5 Also linked with that movement is the Robert E. Lee Monument in Charlottesville, Virginia, the planned removal of which was the catalyst for the deadly Unite the Right rally in August 2017 (fig. 5). Charlottesville’s statue was begun by New York City–born sculptor Henry Shrady, who is best known for the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial in front of the United States Capitol. The statue was completed by Italian immigrant Leo Lentelli after Shrady’s death.6

Not all Confederate monuments were sculpted by artists from outside the South, however. Edward Valentine and Moses Ezekiel were both Richmond-born sculptors and prominent in the field of Confederate memory. Ezekiel served in the Confederate army, while Valentine spent the war years studying sculpture in Europe. Returning to Virginia in 1865, Valentine distinguished himself as a sculptor of Confederate subjects, including the gisant covering Lee’s tomb in Lexington, Virginia, a statue of Lee that is now in the United States Capitol Statuary Hall, and the monuments to Jefferson Davis and Matthew Fontaine Maury on Monument Avenue (fig. 6).7 As for Ezekiel, after his stint in the Confederate army, he left America, first for Berlin, and then for Rome, where he lived for the rest of his life. Over the course of his career, he was knighted in Italy and Germany and received many prestigious honors for his art. His most famous Confederate monument is the colossal bronze memorial in Arlington National Cemetery, commissioned after the establishment of a special section of the cemetery for the Confederate dead in the wake of the Spanish-American War.8 Both Valentine and Ezekiel lived cosmopolitan lives, taking advantage of the best artistic training and facilities for producing sculpture across the United States and in Europe. Like the soldier monuments ordered from international manufacturers, their work reflects the global scope of sculptural knowledge and materials brought to bear on post-Civil War commemorative activities.

With this history in mind, let us turn to an assessment of Confederate monuments within the field of Southern art. Confederate monuments are cosmopolitan works, made by sculptors and artisans from within and outside the region. Their visual language comes from Greek and Roman sources filtered through the Neoclassicism of European and American sculptors in the nineteenth century. And yet, they have been claimed today as key markers of white Southern heritage and culture. The women of the Ladies’ Memorial Associations and, later, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, took ownership of the monuments as one facet of their highly successful campaign to replace the truth of the Civil War with the myth of the Lost Cause. Like the elite woman reading the funeral rite for William Latané in the A. G. Campbell engraving of William D. Washington’s popular painting, they centered their histories of the monuments on their own agency in commissioning them.9 When looking into the archive to learn about the origin of a particular Confederate soldier monument, information about the artist or manufacturer can sometimes be difficult to find. Often an account will include the names of the women involved in fundraising for the monument, the methods they used to raise the money and the amounts they procured, and the ceremonies they enacted in order to dedicate it. As for the monument itself, accounts might specify merely “an Italian sculptor,” or in the case of Northern monument firms such as the Monumental Bronze Company, no information at all.10 For Southern women’s organizations, then, the act of commissioning and dedicating a monument was significantly more important than the facts of its creation. It should therefore not be surprising to see the monuments folded into the neo-Confederate mythmaking that has resulted from the spread of Lost Cause ideology, which recasts the Civil War from a conflict fought to preserve slavery into a battle for states’ rights fought by an agrarian South against Northern industrial power.11

But it is also important to remember that Confederate monuments do not represent the history or heritage of all Southerners or all Americans. As recent protests have emphasized, Confederate monuments are clearly implicated in the history of slavery leading up to the Civil War and the violence and terrorism of Reconstruction, both of which fuel continued racial persecution against black Americans today. Most of these monuments were built between the 1890s and the 1920s, when race relations in the South were at their worst and violence directed toward black Americans was at its highest point. And the siting of Confederate monuments in front of the county courthouse makes this connection explicit: these spaces were implicated in the violence of lynching, a terroristic act perpetrated to suppress all who opposed white supremacist rule. That profound injustice is clearly linked to continued injustices that disproportionately affect black Americans today, including mass incarceration and the police violence that is central to the Black Lives Matter movement. Confederate soldier monuments have long been associated with political and racial power structures that perpetuate violence against black bodies, and the recent debate over their future makes this association clear.12

Just as the ideology of the Confederate monument does not represent all Southerners, its form fails to reflect the folk visual tradition that is one of the region’s great strengths. Confederate monuments are variations on a fairly narrow theme: the exalted human figure on a pedestal. Whether equestrian statues of military leaders, standing portraits of politicians, or soldiers at parade rest, they follow a conventional formula handed down from ancient classical tradition. They communicate power and take up most of the central spaces in the public landscape. But during the same time period in which Confederate monuments have come to dominate civic spaces, African American Southern artists have developed an extraordinary artistic tradition using the materials and spaces available to them. From the yard shows of artists such as Joe Minter and Lonnie Holley to the quilts of Gee’s Bend, these artists have forged a vital visual language that rivals any modern art movement within the mainstream art world. Denied access to public space and prestigious art training, they have used found objects and privately owned land to build worlds for their art. Joe Minter’s African Village in America in Birmingham, Alabama, is one of the few extant examples of the yard show, a tradition that flourished in the Deep South in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement.13 Minter continues to add to his environment, which includes many monuments to the darker moments in American history, from slavery and lynching to recent tragedies such as 9/11 and the Sandy Hook Massacre.14 Yard shows are dying out due to the aging of the generation that produced them, instances of aggressive zoning, the incursions of the art market, and other factors. But these spaces offer an alternative to the sterile Confederate monument. Unlike the traditional monument, which presents as an unchanging and unchangeable edifice, vernacular installations are constantly in flux. Their creators add and remove material, and individual elements break down with exposure to weather and time. Meaning is unstable, and there is always room to add new context or ideas. If the Confederate monument is intended to communicate an inflexible interpretation of history, the yard show allows for nuance, improvisation, and chance.

Some of that improvisational spirit has already made itself evident in spaces where Confederate monuments have been removed. In places such as Durham (North Carolina), Baltimore, and New Orleans, the empty plinths have become charged spaces for a different form of remembrance. These unoccupied pedestals tug at the mind in a way that a whole monument might not, calling attention to the existence of an interpretation of history that the community has decided to retire. In Durham, the granite base of the statue pulled down just days after the Charlottesville riot remains in limbo. North Carolina state law prohibits any alteration to monuments on public property, even those that have been partially destroyed due to acts of iconoclasm. And so the pedestal sits, asking for intervention. On at least two separate occasions, artists have installed guerrilla monuments on the base in place of the Confederate statue in the dead of night: a heart shape last August, and a thicket of defiantly raised fists in November.15 Empty plinths in other cities have also become targets for graffiti and other extralegal installations. Perhaps there is a way forward in which these unsettling objects could become a counter-monument, a celebration of the resistance against Confederate ideology.

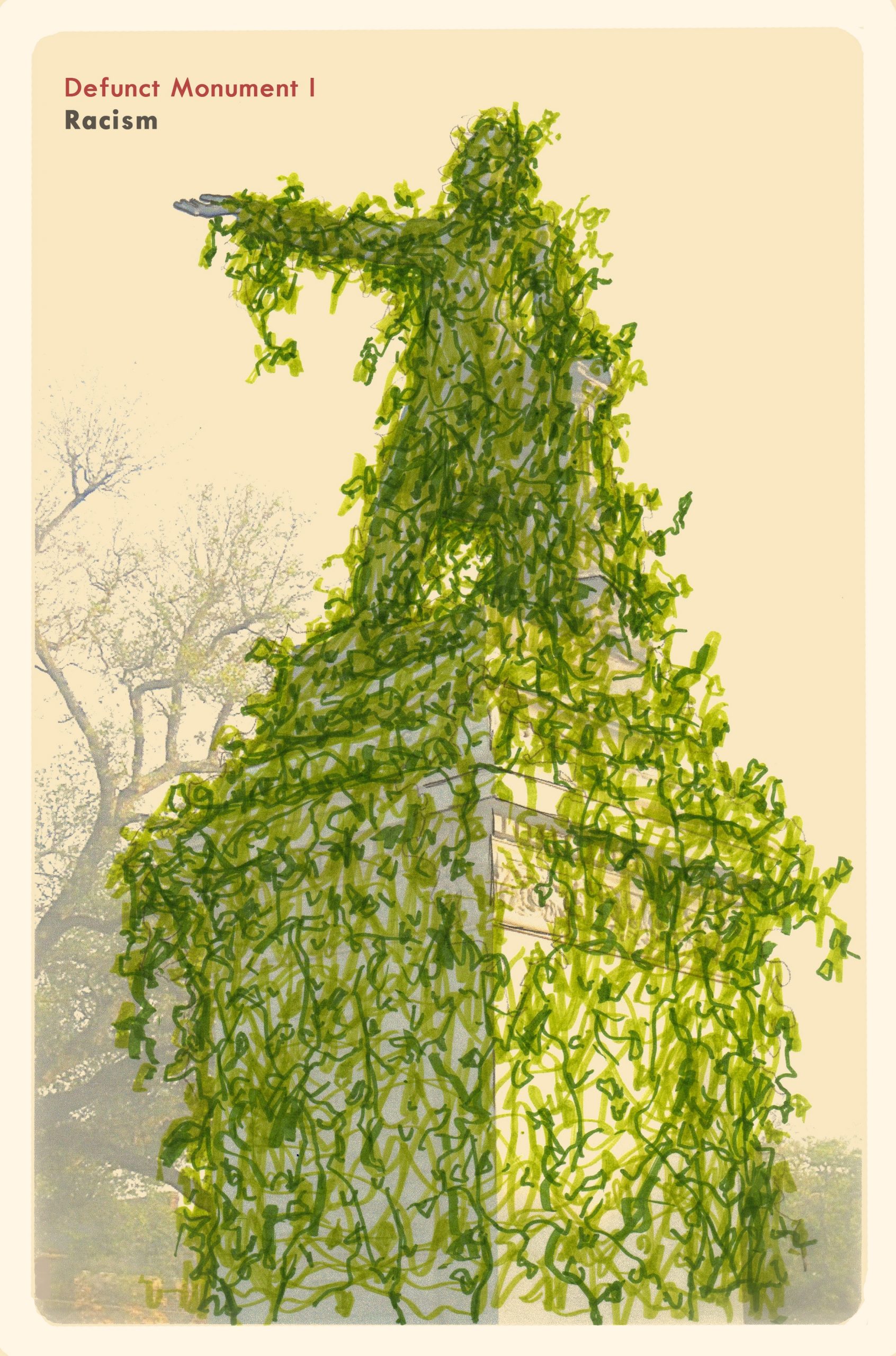

Several artists have also imagined one other powerful force that could overtake the Confederate monument: kudzu. This invasive vine, native to Asia, was introduced to the American Southeast in 1883 and has gained a reputation as “the vine that ate the South.” Fast-growing and difficult to eradicate, kudzu exists simultaneously as a nightmare and a source of regional pride. In 2017, Dave Loewenstein, a muralist and printmaker based in Lawrence, Kansas, made a series of postcards for “defunct monuments,” in which he imagined the vine consuming monuments associated with racism, materialism, and militarism (fig. 7).16 Loewenstein’s postcard shows the now-removed monument to Jefferson Davis in New Orleans completely obscured by kudzu vines, rendering all but the statue’s silhouette virtually unrecognizable. Shortly after he published the illustration, a group of anonymous artists based in Charlottesville, Virginia, used it as a model for their Kudzu Project. For the project, more than thirty knitters knitted hundreds of kudzu leaves, arranged them in loops and vines, and tossed them over the top of local Confederate monuments, taking photos of their work for posterity in each instance before the vines could be removed by authorities (fig. 8).17 Kudzu also factors into Aaron McIntosh’s Invasive Queer Kudzu project, in which he uses the weed as a metaphor for how queer people are viewed in American society (fig. 9). Hailing from Kingsport, Tennessee, and currently based in Richmond, Virginia, McIntosh holds workshops in which attendees make leaves telling aspects of their own stories, and he advertises for the workshops with images of the vine overtaking local monuments.18 In the spring of 2019, McIntosh reimagined the project with a life-scale installation of the kudzu vine taking over a toppled Confederate monument at Richmond’s 1708 Gallery.19

These artists may have hit on a fitting metaphor for the Confederate monument, imagining an alternate future in which these monuments are reclaimed by the land on which they stand. Like kudzu, the Confederate monument is an invasive species. Born out of a classical visual tradition and imported by travelers to foreign shores, the monument form took root in soil ideally suited for its cultivation. In the 150 years since the Civil War, approximately 1500 separate memorials to the Confederacy have appeared across the United States, spreading the Lost Cause myth and perpetuating the injustices begun under slavery and the rifts that have kept the nation from moving forward. In the manifesto on their website, the artists of the Kudzu Project liken the romanticized architectural ruin covered in kudzu vines to the ideology of the Lost Cause, which cloaks slavery and racism in the pretty language of gentility and honor. For both invasive plants and invasive ideas, the way forward to a healthier landscape is to fight to eradicate the invader and to uproot it from the soil that protects it. But as that fight continues, it is comforting to imagine one invasive species covering and overwhelming the other.

Cite this article: Sarah Beetham, “Confederate Monuments: Southern Heritage or Southern Art?” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9844.

PDF: Beetham, Confederate Monuments

Notes

- See Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997); Gaines Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865 to 1913 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987); Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson, eds., Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2003); Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008); and Thomas J. Brown, Civil War Canon: Sites of Confederate Memory in South Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015). ↵

- For zinc and white bronze statues, see Carol Grissom, Zinc Sculpture in America, 1850–1950 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2009). On the production of Civil War soldier monuments in the North and South, see Lewis Waldron Williams, “Commercially Produced Forms of American Civil War Monuments” (MA thesis, University of Illinois, 1948); Michael W. Panhorst, Lest We Forget: Monuments and Memorial Sculpture in National Military Parks on Civil War Battlefields, 1861–1917 (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 1988); Sarah Beetham, “Sculpting the Citizen Soldier: Reproduction and National Memory, 1865–1917” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2014). ↵

- John Brainard Mansfield, The History of Tuscarawas County, Ohio (Chicago: Warner, Beers, 1884), 740; Frank M. McKenney, The Standing Army: History of Georgia’s County Confederate Monuments (Alpharetta, GA: W. H. Wolfe Associates, 1993), 97–99. ↵

- McKenney, The Standing Army, 56–58; “‘Dutchy’ Comes off his Perch,” Elberton Star, August 16, 1900; Grissom, Zinc Sculpture in America, 529; “The Fall and Rise of ‘Dutchy,’ Elberton’s First Granite Monument,” (Elberton, GA: Elberton Granite Association, 1982), 2–6. ↵

- Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves, 129–161; Maurie McInnis, “‘To Strike Terror’: Equestrian Monuments and Southern Power,” in The Civil War in Art and Memory, Kirk Savage, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 125–46. ↵

- Jacey Fortin, “The Statue at the Center of Charlottesville’s Storm,” New York Times, August 13, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/13/us/charlottesville-rally-protest-statue.html; Paul Duggan, “Charlottesville’s Confederate Statues Still Stand—and Still Symbolize a Racist Legacy,” August 10, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/08/10/charlottesvilles-confederate-statues-still-stand-still-symbolize-racist-past. ↵

- Lorado Taft, The History of American Sculpture (1903; reprint, New York: Macmillan, 1930), 522; Pamela H. Simpson, “The Great Lee Chapel Controversy and the ‘Little Group of Willful Women’ Who Saved the Shrine of the South,” in Mills and Simpson, Monuments to the Lost Cause, 85–99. ↵

- Wayne Craven, Sculpture in America (1968; reprint, Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1984), 337–38; Karen L. Cox, “The Confederate Monument at Arlington: A Token of Reconciliation,” in Mills and Simpson, Monuments to the Lost Cause, 149–62; Taft, The History of American Sculpture, 262–63. ↵

- Mark E. Neely Jr., Harold Holzer, and Gabor S. Boritt, The Confederate Image: Prints of the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), ix–x; Drew Gilpin Faust, “Race, Gender, and Confederate Nationalism: William D. Washington’s Burial of Latané,” in Southern Stories: Slaveholders in Peace and War (Columbia: University of Missouri Press: 1992), 158; Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past, 52–58. See also Rachel Stephens, “‘Whatever is un-Virginian is Wrong!’: The Loyal Slave Trope in Civil War Richmond and the Origins of the Lost Cause,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://journalpanorama.org/article/whatever-is-un-virginian-is-wrong. ↵

- For a period source that uses this strategy extensively, see Mrs. B. A. C. Emerson, Historic Southern Monuments: Representative Memorials of the Heroic Dead of the Southern Confederacy (New York: Neale Publishing, 1911). ↵

- William A. Blair, Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South, 1865–1914 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 2. For other perspectives on the Lost Cause, see Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy, 3–10; Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865–1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980), 1–17; and David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 37–38. ↵

- Sherrilyn Ifill, On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-First Century (Boston: Beacon Press, 2007), 8–9; W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993); and Philip Dray, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America (New York: Random House, 2002); and Sarah Beetham, “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter,’” Public Art Dialogue 6, no. 1 (2016): 9–33. ↵

- See Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Magic City Modern: A Short History of the Birmingham-Bessemer School,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://journalpanorama.org/article/magic-city-modern. ↵

- Michael Tortorello, “Scrap-Iron Elegy,” New York Times, April 24, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/garden/joe-minters-african-village-in-america.html; Paul Arnett, “Joe Minter’s African Village in America,” soulsgrowndeep.org, accessed March 27, 2020, https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/artist/joe-minter. ↵

- “Heart Sculpture Installed on Durham Pedestal Where Confederate Statue Stood,” WRAL.com, August 24, 2017, https://www.wral.com/a-heart-now-rests-on-the-pedestal-where-durham-confederate-statue-stood/16901550; “Durham Removes Heart Placed Atop Confederate Monument,” ABC11.com, August 24, 2017, https://abc11.com/politics/durham-removes-heart-placed-atop-confederate-monument/2337089; Virginia Bridges and Mike Williams, “New Sculpture Placed Where Confederate Soldier Once Stood in Downtown Durham,” Herald-Sun, November 17, 2017, https://www.heraldsun.com/news/local/counties/durham-county/article185164618.html. ↵

- Dave Loewenstein, “Defunct Monuments,” davelowenstein.com, accessed March 27, 2020, https://www.daveloewenstein.com/studio-projects#/defunct-monuments. ↵

- “The Kudzu Project,” accessed March 27, 2020, https://www.thekudzuproject.org. ↵

- Marilyn Drew Necci, “Invading the Narrative: Aaron McIntosh’s Invasive Queer Kudzu Project,” RVAmag.com, August 20, 2018, https://rvamag.com/art/invading-the-narrative-aaron-mcintoshs-invasive-queer-kudzu-project.html; Aaron McIntosh, “Invasive: Amassing Southern LGBTQ Stories,” accessed March 27, 2020, https://invasivequeerkudzu.com. ↵

- 1708 Gallery, “Invasive Queer Kudzu: Richmond,” 1708gallery.org, accessed May 8, 2020, https://www.1708gallery.org/exhibitions/exhibition-detail.php?id=100. ↵

About the Author(s): Sarah Beetham is Assistant Professor and Chair of Liberal Arts at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts