The Love in Labor: Reconsidering Amateurism in Sister Gertrude Morgan’s Performances and Paintings

Sister Gertrude Morgan (1900–1980) entered a buzzing, celebrity-filled orbit when she appeared in the September 1973 issue of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. This entrance on the surface appears incongruous and unlikely: Morgan was an African American southern woman from the outskirts of New Orleans who was steeped in Holiness-Pentecostal religious traditions, while Warhol, by then the best-known American Pop artist, established his career in the pulsating cityscape of Manhattan, producing likenesses of Elizabeth Taylor and Elvis in iconic silkscreen paintings. The pages of the September issue heighten this contrast as well, inserting Rosemary Kent’s story about her visit to Morgan’s “tiny mission” between photos of glamorous models and interviews with movie stars and porn actors.1

Interview was shifting its focus from the New York underground film scene to popular entertainment under Kent’s editorship; still, her portrayal of Morgan’s rough-hewn novelty and authenticity suited its trendsetting readership.2 Morgan was seventy-three years old at the time of Kent’s visit, and she was a missionary who could typically be found evangelizing on the streets of New Orleans or in services she hosted in her Lower Ninth Ward home. What interested the editor, however, was Morgan’s amateur, nonacademically trained status as a painter and musician; especially noted are her lack of interest in professional growth (“success as an artist is really and truly the last thing on her mind”); her seeming immunity to commercial markets (as “Louisiana’s super-best tourist attractions that will never get over-commercialized”); and her tendency to use cheap materials (“dimestore paints, crayons, and occasionally a ballpoint pen”).3 Like her irregular handwriting reproduced for Kent’s title, these details frame Morgan’s modest ambition and unschooled practice into a discovery of an unlikely artist from an unlikely place. One could say Morgan fascinated precisely because she was a “nonartist artist,” reinforcing the kinds of paradoxes that ran through Warhol’s art and the quixotic artistic identity he fashioned for himself. 4

This essay does not position Morgan as an underrecognized Pop artist; it instead explores some of the implications that follow from art practices that are more informed by vernacular culture than by academic or high modernist discourse—objects taking on fine art forms but emerging outside schooled traditions and the collective activity of established art worlds.5 Indeed, recent scholarship has shown how these characteristics of amateurism and fine/vanguard/modernist art are discursively co-constitutive, one inextricably—if not also problematically—tied to one another. Marci Kwon and Kim Grant have demonstrated how mid-twentieth-century gatekeepers of modernism in the United States, such as the Museum of Modern Art and ARTnews, historically resisted the incursion of amateurs into their ranks, despite an egalitarian ethos of individual originality that both institutions valued and briefly championed.6 John Ott further demonstrates the reductive, biased effects of amateurism when intersected with race. In his probing analysis of Palmer Hayden’s career, Ott defines amateurism not only as a sociological fact for many African American artists who had limited opportunities for consistent training and exhibition—necessitating that they find occupations other than fine artist—but also a discourse heightened by white philanthropic organizations to reinforce the marginality of black artists and obscure their professional achievements.7 Kent’s interest in Morgan hinges on the discovery of artistic life at the margins. But unlike Palmer Hayden, whose painting The Janitor Who Paints (c. 1930; Smithsonian American Art Museum) satirizes the politics of amateurism when defined in terms of technical deficiency (and condescending patronage that follows), Sister Gertrude Morgan’s different positionality urges us to consider other dimensions of this malleable discourse. Her artistic practice is situated farther away from the gravitational center of professionalism, which highlights ways that amateurism can be understood in positive and more nuanced terms.

The 2018 exhibition organized by Lynne Cooke, Outliers and American Vanguard Art, aids such a prospect. It reorients the high/low and insider/outsider binary that reverberates in the discourse on amateurism by recasting marginality in terms of variance that invites inquiry, rather than difference that triggers categorization. As Cooke writes, in thinking in terms of “outliers,” this paradigm reframes difference as “a position of strength: a place negotiated or sought out rather than predetermined and fixed.”8 If the history of amateurism has been weighted toward the derogatory and dismissive, in our present moment approaches to amateurism can illuminate other motivations, imbricated practices, and intersecting histories that inform artmaking.

From this perspective, Gertrude Morgan was not simply the amateur of Kent’s schematic portrayal but an artist possessing creative fluency in traditions of black Holiness-Pentecostal religious performance. This charismatic environment—emerging from a network of churches colloquially described as “sanctified” by adherents—nurtured Morgan’s abilities as a preacher, singer, and evangelical teacher. This essay explores the expressive complexities of her sanctified performances, in which religious devotion precipitated a series of aesthetic translations between sonic, vocal, embodied, and visual realms. By recovering the motivation of love that set aloft the freedom in Morgan to determine her artistic path—that which she voiced in terms of the pleasures of intimacy with God—we witness how amateurism operates as a critical position committed to other allegiances and defined by other competencies, even as it interacts and interweaves with the formal codes, networks, and sociocultural norms of professionalism.

Morgan’s Sanctified Performances

In Leigh Eric Schmidt’s evocative phrasing, “the conversational intimacies of orality” were central to the modern evangelical Protestant experience, and especially to the black sanctified faith that flourished within early twentieth-century rural and urban working-class communities.9 Consider, first, the event with which Morgan introduces her autobiography in A POEM OF MY CALLING (fig. 1): “My Heavenly Father called me in 1934 . . . the strong powerful words he said was so touching to me . . . Go ye into yonders [sic] world and sing with a loud voice for you are a chosen vessel to call men women girls and boys.” Not only does God speak in ways that affect one deeply and personally, but in Morgan’s specific calling, he also gives the mandate to perform the same kind of speech. This mandate to “call” others, however, comes with an important difference: as a “vessel,” she was the messenger of words belonging to someone else. Therefore, defining the sacred idea of calling is the privileged, private, and mysterious nature of divine discourse and devotional labor in service to another.10 So when Morgan declares in writing that “My new name [is] Anna” at the end of her poem, it can be understood as a transformation premised on deepening intimacy with God. As the elderly prophetess who foretold the birth of Christ in St. Luke’s gospel, Anna was authorized to deliver God’s revelations just as Morgan was centuries later. Dedicated service to and trust in this calling establish the interpersonal grounds of love and desire for the sacred “other” that deepen as the poem continues.

As the second half of the poem discloses, Morgan received another revelation: she was “the wife of my redeemer,” Christ. A metaphor for the gift of full sanctification following religious conversion, the Bride of Christ signified the perfected union between a believer with God. As the bride, the believer’s will was subsumed by God’s power through the Holy Spirit that now inhabited his or her body—a tenet implying possession of heavenly power to enact divine will on earth. 11 While offering the possibility of Christian perfection and an avenue for claiming religious authority, sanctification was understood by Holiness-Pentecostal believers as a continual process requiring active maintenance, moral obedience, and the daily work of keeping oneself “unstained” by worldly desires.12 Therefore, Morgan’s sanctification pivoted on the embrace of God’s commission to spread the Christian gospel by “sing[ing] with a loud voice.” By her own account, Morgan accepted this calling by leaving her home in Columbus, Georgia, in 1938, and settling in New Orleans on February 26, 1939, where she cared for young orphans for eighteen years and taught “holiness and righteousness” as a missionary. That Morgan composed her story as a poem and donned all-white clothing to display her bridal identity (as she portrays herself on the page’s upper left corner) affirms the imperative of sanctified devotion to testify publicly.

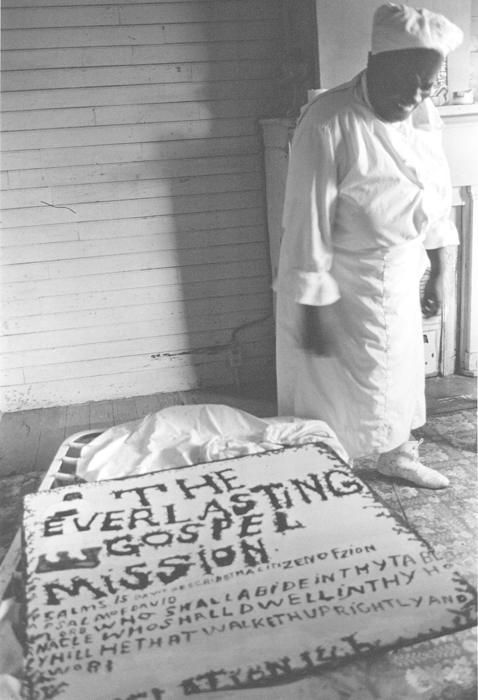

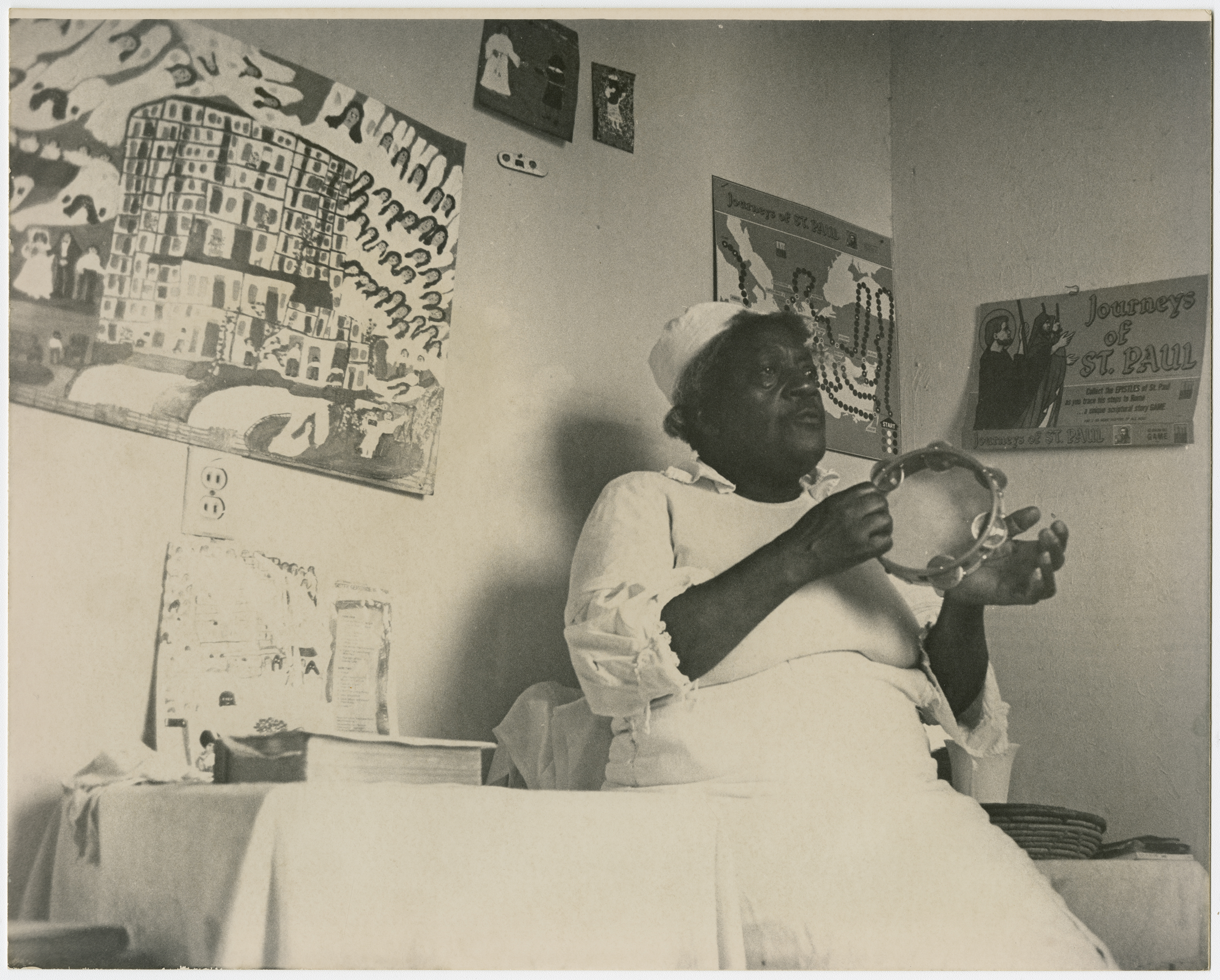

Lest these doctrinal points seem too dry and transactional, listening to recordings made between the spring of 1959 and 1971 offers a sense of the rapturous emotion and forms that shaped Morgan’s sanctified dialogues. These were recorded by Larry Borenstein, owner of the Associated Artists Gallery in the French Quarter, during sessions that sometimes included tourists, passersby, or aficionados of New Orleans–style jazz eager to catch echoes of its origins (figs. 2, 3).13 In one exceptional instance, Morgan’s session resulted in a 1971 commercial recording entitled Let’s Make A Record. 14 Consistent with American evangelicalism’s historical embrace of sound technologies and production of African American religious records, Morgan used these opportunities to sing and spread the gospel message.15 These exist today in at least twenty extant tracks.16

The opening prayer from a recording dated April 26, 1959, is both an intimate address to God and a performance of intimacy for those in the session (audio 1). On the one hand, she thanks him for the privilege of “broadcasting your word and lifting up your name” as the means by which people would come to faith; she also sweetly offers more thanks for the “beautiful sunshiny day” and her health toward the end of her prayer. Carried by the lilting strum of the guitar, these sections reflect the accord Morgan bears with her divine addressee from the position as bride and missionary for his cause. On the other hand, imperatives punctuating the middle of her prayer obliquely implicate her presumably unconverted audience: first in her petition for God to “bless this place, bless the manager, bless everyone that’s under the sound of my voice” and then in her appeal that he “wake up the careless and unconcerned.” Amid this three-way call-and-response passage, Morgan intones a rhetorical question (“help them to ask themself [sic] a question, ‘What time is it?’”) and supplies the answer as it surges through her vocal cords: “Time for me to wake up to my sense of duty and get about my father’s business.” Here, Morgan effectively provides “the careless and unconcerned” with a consciousness-raising script as a conversion strategy, directing listeners into oral modes of confession, prayer, and testimony which, in the sanctified church especially, are the seeds of belief and Christian devotion.17

Audio 1. Sister Gertrude Morgan, prayer, April 26, 1959. Recorded by Larry Borenstein. Courtesy of the Borenstein Family, https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/AUDIO-1-Gertrude-Morgan-Prayer-April-26-1959.mp3

This prayer demonstrates Morgan’s ability to “enter simultaneously into familial, or testimonial, and public, or competitive, discourse,” traits that anchor Mae G. Henderson’s theory of “speaking in tongues.”18 Adapted from the Holiness practice of glossolalia, or ecstatic speech, “speaking in tongues” for Henderson marks “the plural aspects of self that constitute the matrix of black female subjectivity.”19 She discusses this plurality along two kinds of address: the first kind speaks from a desire for solidarity and identification within experiences of alienation, while the second mode of address asserts difference from a position of otherness. This latter engagement draws upon a Bakhtinian model of language that negotiates a range of hegemonic and non-hegemonic discourses. The appeal of Morgan’s prayer to both listening audiences and God embody these multiple levels of discourse that seeks to communicate interpersonally from a spiritual site of privileged exchange that the other cannot necessarily see or understand. The point is to enrich—through challenge and affirmation—both parties’ understandings of self and other through these characteristics of black women’s speech.20

“Let Us Make a Record” from the album released as Let’s Make a Record, helps us understand how Morgan marshalled musicality to intensify the interlocutory characteristics of “speaking in tongues” (audio 2). Following the opening tambourine clap, her opening words—“Ah, let us make a record / for my Lord”—is a brilliant act of signifying that describes the LP she is presently creating that will also function as an enduring testament to her religious labor. Listen to how subtle shifts in her chanted words further expand the temporal scale of “making a record” and define its scope. Beginning with the plural imperative “let us,” the next lines substitute “prophet Isaiah” and “Ezekiel” as ancient precedents for her work, implying that the “record” Morgan has in mind is the writing of prophecy. In the final iterations of the song, the lyrics snap back to address the listener in the present as her declarations of desire (“I wanna make a record…”), coupled with appeals (“don’t you wanna make a record…?) seek to rally us around her religious cause.

Audio 2. Sister Gertrude Morgan, “Let Us Make A Record,” 1970. True Believer Records, https://youtu.be/3WZjl1v9igA

Tuning into the percussion and vocal aspirations of the track also accentuates these positional shifts. About midway through the song, following ecstatic shouts, the rhythm breaks as Morgan speaks from her position of sanctified difference: “Come on let’s make a record / give up the world / give up Lucifer.” From minute 2:00 and after, the frequency of her shouts (“Hallelujah,” “Glory,” and “Hosanna”) accelerate and grow higher in pitch, such that Morgan seems to have ascended temporarily from the earthly space of the performance to another realm where she is subsumed by the Holy Spirit, and God becomes her primary audience. The hand-slaps and rattles of her tambourine assist in effecting this spiritual elevation. But as the track ends and calls for praise replace the verses, we are left with only the sonic insistence of this tambourine bass/baseline and the memory of Morgan’s vocals—as if registering the brief yet intense passage of the Holy Spirit.

Recorded under Borenstein’s auspices and in the musical environment of postwar New Orleans, Let’s Make a Record was commercially produced to capture Morgan’s sound in as high fidelity as possible. Consequently it generates a sense of nearness we may feel as listeners, close enough to perceive every throaty melisma and crescendo of her voice as it burrows into the vowels of “record” and “lord” and her lower vocal register (this effect is helped by the baps on the tambourine that are akin to forceful, short exhalations). This sensation of proximity is part of the pleasure of listening, which is a crafted effect rather than an unmediated sound.21 As Jerma A. Jackson explains, sanctified music came of age amid the rapid growth of the sanctified church in urban and rural areas throughout the 1930s and 1940s; a burgeoning recording industry replete with booking agents, promoters, and publishers (especially marketing “race” records beginning in the 1920s); and growing consumerism of black gospel music that peaked in the 1950s.22 Engineered to create the dense textures of Morgan’s voice, these 1971 recordings capture an experience that is simultaneously immediate in the perception of its grain yet spectral in its disembodiment.23 We can accept these recordings as capitalist appropriations of an “authentic” black voice, to be sure, but what if we centered our reading from Morgan’s perspective and the creative agency such performances afforded her?24 What insights arise if we consider Morgan’s embrace of and performances for sound technologies as a decision intentionally made for how it could complement, rather than exploit, her mission and religious practice?

These questions help recalibrate the object of our listening from signs of religious authenticity to think about how sanctified performance functioned for the artist, and what it afforded her, in a field of practice.25 An earlier performance of “Let Us Make a Record” from August 19, 1961, can disabuse us of any belief we might have in sound recording as an unmediated process or in Morgan’s consistency as a performer (audio 3). It is no doubt a raw recording, but no amount of editing could tighten or polish the instrumental accompaniment to Morgan’s guitar in this instance. On the tape, her chant comes across as a holler attempting to dominate the improvised undercurrent of George Lewis’s clarinet and “Kid” Thomas Valentine’s trumpet. Adding to the disparate musical lines are strums from Morgan’s untuned guitar that resonate with fulsome, if not also uncontrolled, sound. The repeating melody of the song mercifully adds some degree of harmony in the moments when the instruments unite in a three-note response, “for my Lord,” to Morgan’s musical call; however, the overall performance struggles to cohere.

Audio 3. Sister Gertrude Morgan, George Lewis, and “Kid” Thomas Valentine, excerpt of “Let’s Make A Record,” August 19, 1961. Courtesy of the Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/AUDIO-3-Gertrude-Morgan-Thomas-Lewis-Lets-Make-a-Record-August-19-1961.mp3

This recording evinces an important aspect of Morgan’s performance and ministry that more polished audio recordings do not obviously register. Remember the terms of her calling: “go ye into yonders world and sing with a loud voice.” Whether the outcome was harmonious or not, what ultimately mattered was the going and the doing: Morgan’s spiritual labor was performative, prompting a sanctified body towards fulfillment of its calling. Or as The Gospel Keys instruct listeners with this bouncing sanctified song: “When the Lord gets ready / you’ve got to move.”26 If spontaneity and improvisation were signs of a believer moved by the spirit to witness, then Morgan’s willing embrace of sound recording technologies amplified, in more ways than one, the evangelistic mission to which she was already committed.27 It affirmed her sanctified identity as one that accepted opportunities as they came, including ones that led her into professional contexts. Indeed, creating Let’s Make A Record seems to have been somewhat unplanned: Borenstein was working with a film crew on a separate project when he took advantage of their equipment to set up a recording session.28 Yet by design, Morgan’s willingness to record constitutes having listeners in the present as witnesses to her acts of devotion.

Audio 4. Elder Utah Smith and Congregation, “Two Wings,” 1947. Courtesy CaseQuarter Records https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/AUDIO-4-Utah-Smith-I-Got-Two-Wings.mp3,/span.

Morgan did not seek nor attain the sensational popularity of other sanctified musicians, a fact partially explained by different configurations of talent, opportunity, and choice that defined her expressive practice. Elder Utah Smith, for example, hosted tent revival meetings in the 1940s before moving into a converted warehouse in New Orleans named “A Two-Winged Temple in the Sky,” which could hold more than 1,200 people. Smith led his audiences in call-and-response musical worship services until his death in 1965, and he often did so spectacularly, donning a pair of seraphim wings as he played his electric guitar (audio 4, fig. 4).29 It is easy to imagine the jolting effect of the guitar on a crowd when activated by Smith’s rumbling riffs and skipping guitar licks. Though Morgan and Smith were sanctified contemporaries in the same city, Smith’s talent and position as a church leader afforded him prominence within a larger regional network of sanctified churches and on the radio that Morgan never achieved through her music alone.30 When Let’s Make a Record was issued, Borenstein reproduced Morgan’s painting on the album cover (several of which she brightened with colored paints) suggesting that music was a vehicle for promoting her singular, visionary art as opposed to art boosting her musical talents (fig. 5).

Comparing the rougher, less sophisticated, and improvisational musicality of the missionary to Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s professionalized talents further underscores the way skill can alter the terrain for realizing one’s artistic possibilities. A sanctified contemporary of Morgan’s, Tharpe was a guitar virtuoso, immensely skilled at fingerpicking, and had a vocal style that attracted recording producers and catapulted her international popularity. One hears these qualities in “Rock Me,” a song that cloaks an appeal for divine comfort in the bluesy tones of a romantic love ballad (audio 5).31 Buoyed by a big-band orchestra, “Rock Me” goes down smoothly with its swinging beat. By contrast, “Let Us Make a Record” forces listeners to contend with its gravelly, haunting insistence. Indeed, Tharpe’s music had become so popular through her recordings and concerts that her crossover career aggravated controversies over the proper place of gospel music in a consumer culture.32 If Tharpe’s performances before secular audiences cast her religious commitments in doubt, then Morgan’s brief foray into commercial recording comes into focus as a relatively safe venture in which the artist did not risk compromising her spiritual motives. After all, she was making records for her Lord and ostensibly not for herself.

Audio 5. Sister Rosetta Tharpe with the Lucky Millinder and His Orchestra, “Rock Me,” 1941. Re-released on Sister Rosetta Tharpe: The Gospel of the Blues, compact disc, MCA Records, 2003, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rZPLTnohyjA

The aesthetic differences exemplified by Morgan’s and Tharpe’s performances held similar currency in popular culture as well. For by the time Morgan stepped into Borenstein’s gallery in the 1960s, her style was out of step with the popular gospel sounds of the day. Her rough-hewn sounds seemed obsolete and were cherished as such; captured as relics of traditional folk or roots music, they belonged to a picturesque imaginary visualized by the artists who depicted jazz musicians and romantic cityscapes to sell at Associated Artists Gallery.33 Yet when considering how Morgan translated sanctification’s polyvocality, sensations, and performative dimensions into the realm of the visual—that is, how she acted—Morgan’s “old-time religion” crackles beneath the patina of age and vibrates with new energy.

Morgan’s Visual Vocality: Pleasures of Another Kind

Morgan’s visual practice exemplifies the way sanctified faith could spur a believer into exciting and new aesthetic and cultural territory. As the story goes, Morgan was already creating pictures as didactic illustrations for her Bible lessons at an orphanage she ran with two others. Once that operation disbanded in the mid-1950s, however, she pursued her calling alone as the Bride of Christ. It was at this juncture that she met Borenstein, began performing at the gallery, and was encouraged to sell her artwork. Some of her paintings appear most like visual translations of vocal performance. In Calling the Dry Bones, a full-length figure of the Bride of Christ stands before a simple tabletop with accessories for her services (fig. 6). She addresses viewers directly through the cascades of handwritten speech: on the left she condemns those who indulge “worldly lusts,” while on the right she delivers lines from the popular spiritual “Dry Bones.”34 The visual and graphemic register of the drawing, however, offer a different insight in the absence of an audible voice. Not only is her writing an index of the sanctified vessel responsible for the drawing’s script, but her delicately outlined figure testifies to the very power cited in the song to recompose and regenerate dead bones into a spirit-filled being.

Morgan discovered in painting further pleasures that veer towards the mystical. The Lord’s Wife, #1 is a rare instance of the artist-missionary engaging painting thematically in context with her spiritual life (fig. 7). The scene shows the artist sitting upright in her colorfully appointed bed, with legs extended, surrounded by spotted white rectangles. Other details indicate the fixtures of a standard bedroom—a draped window, a single lightbulb dangling from a string, a chest of drawers, some fringed area rugs, and whitewashed furniture—that accord with the few extant photographs of her spare interior (fig. 8). Yet, the commodious bed in the painting attracts the eye with its bright, dappled colors; such are the transformational possibilities of art to reimagine the material world.

Words written in the upper right contemplate this idea. Starting to the immediate right of the green bowl, Morgan informs viewers, “[T]his is a mystery work God told me to go get up in the middle of that bed and rest. And now I’ll do so much and so much of my work at a time and when I get tired [I] just lean on back and rest.” Squeezed between these lines is a citation of 1 Corinthians 15:51 that supplies the scriptural insight into her report: “Behold, I show you a mystery: we shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed.” The crucial difference between Morgan’s testimony and scripture pivots on three different meanings of sleep as a biological need, a state of metaphysical death, or a period of restfulness that is also spiritual wakefulness. The “mystery work” to which she refers gets at these seeming paradoxes, in which Morgan frames resting as responsive action to God’s call that precedes spiritual transformation, while sleep describes a state of spiritual death.35 Therefore, in Morgan’s usage, rest and sleep describe two divergent paths that either ascend out of earthly constraints or remain bound to them. The alertness of her self-portrait—arresting eyes comprised of merely six touches of paint—signals the path of transformation that she has chosen.

Through this oblique testimony, we learn that God called Morgan to rest, and that she evidently integrated painting as a part of this response. Tellingly, the eight spotted fields signify a delight in marking a surface with paint. We know that Morgan sometimes recreated her own paintings in her art.36 Yet these hot orange spots lack any pictorial specificity. Instead, and like the cacophonous version of “Let’s Make a Record,” they stand in as evidence of the maker’s enraptured, spirit-led touch. In this sense, Morgan’s signatures—“the two lord’s wife Prophetess Gertrude Morgan” at top and “Missionary” at the bottom—seem like precautions. Lest pleasures of art overindulge the corporeal limits circumscribed by sanctification, these titles reframe and license her painterly marks as traces of the Holy Spirit’s spontaneity.37 Painting could also be a mystery work.

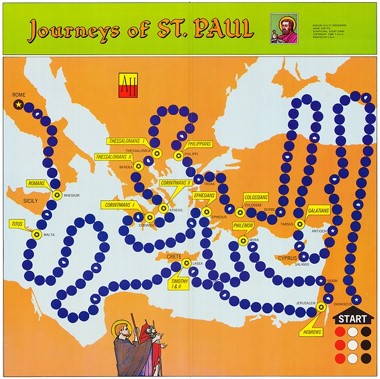

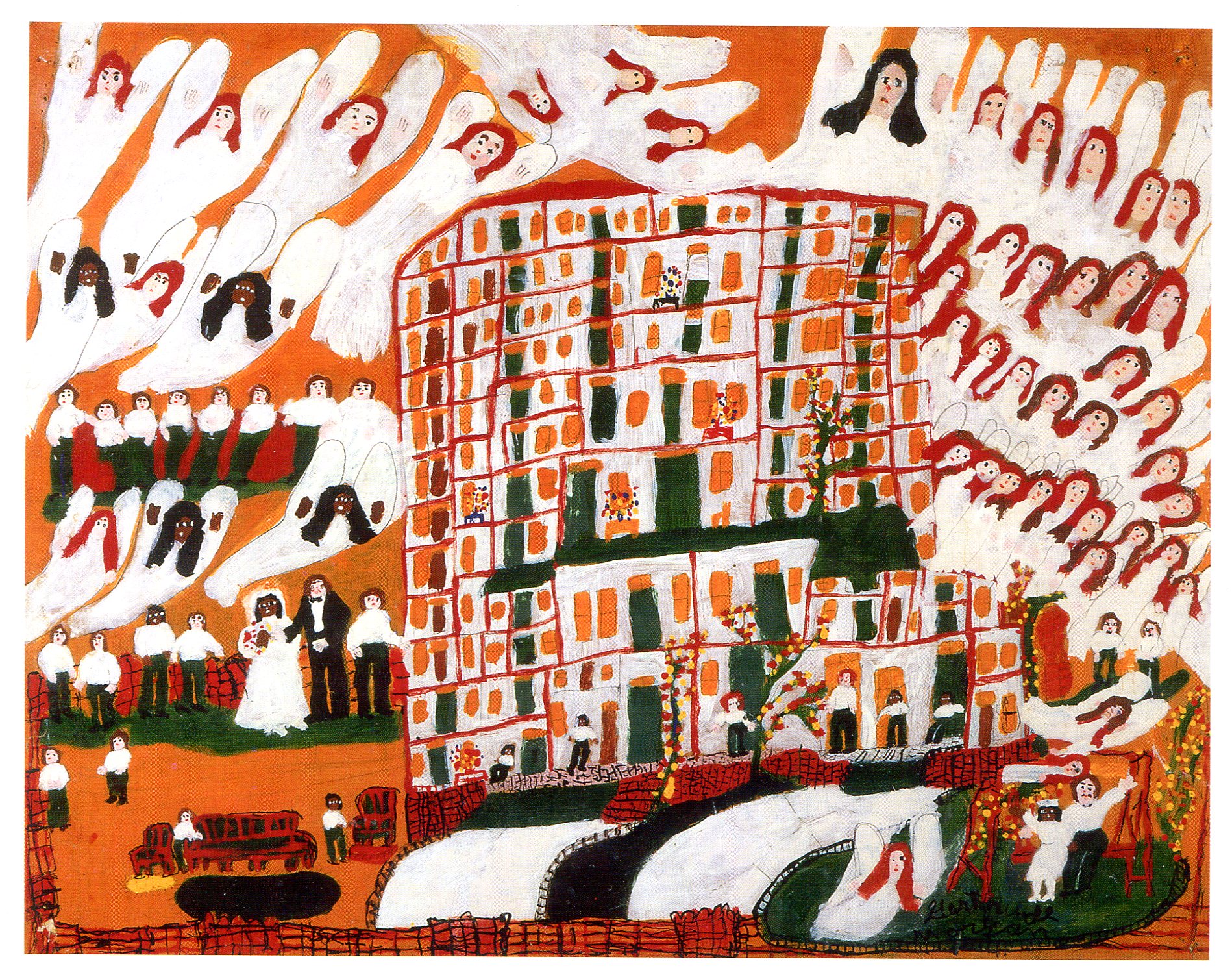

The expressive relationship between dots and the Holy Spirit’s motility may have come intuitively to Morgan, though archives suggest that popular sources may have also informed her visual aesthetic. In a photograph by Jules Cahn, we see two pictures posted on the wall of the rearmost room, a gameboard for the Journeys of St. Paul of 1968, and its box cover (figs. 9, 10). The gameboard delineates St. Paul’s first-century missionary voyages from Damascus to Rome. The path players traverse consists of a meandering line, akin to a strand of blue beads, laid upon a ground of bright orange and white and capped by an equally bright band of green. Hanging on Morgan’s whitewashed walls, such high-key colors could rivet one’s vision to this object—as could the New Jerusalem painting that hangs like its pendant (fig. 11). In a painting she inscribed Paradise: I no we can Reign here [sic], Morgan elaborates on the optical intensity of the gameboard while disrupting the meandering line of dots (fig. 12). The dabs of orange from The Lord’s Wife, #1 explode in formations of red and green, while Morgan adds black and white specks to outline the plantlike forms. On the verso of the work, there are four references to love and the life hereafter that guide the sense of what Morgan intended for the viewer to see: the same visions of heaven that John the apostle wrote about in Revelation—a “flash of the spirit,” in Christianized terms, that suspends ordinary time.38

Morgan’s ecstatic visuality of color and dots in Paradise recalls the throbbing, insistent stylings of her sanctified performances. In terms of visual culture, they also resonate with Ernst Gombrich’s concept of amor infiniti, an expressive desire that “transmute[s] redundancy into plenitude and ambiguity into mystery.”39 Complementing Gombrich’s psychological profile of decorative patterning is Zora Neale Hurston’s idea of “the will to adorn,” which she observed among everyday black communities; it illuminates the dignifying, affective register behind Morgan’s visual practice that “does not attempt to meet conventional standards, but satisfies the soul of its creator.”40 Poignantly, Morgan reveals what lies at her soul’s center: the small vignette of the bride and her groom that is the visual respite of the painting and also the compositional key. Christ depicted as divine love incarnated is nothing new, but to personalize that image with a self-portrait is Morgan’s bold disclosure.41 Through this motif, Morgan displays love’s intimate reach as she knew it.

Love in Artistic Labor

When Julia Bryan-Wilson and Byron Kim expound upon the etymological root of amateurism in the Latin verb amare, meaning “to love,” it is to remind us of amateurism’s priority of pleasure over (but not necessarily exclusive to) other motivations.42 Whether mobilizing the politics of domesticity, gender, and class associated with craft or embracing the unhurried, meditative nature of completing one painting every Sunday, both Bryan-Wilson and Kim underline how amateurs’ investment in making emphasizes less the cultivation of skill than it relishes the artist’s openness and her alertness to the materials at hand in reaching different creative ends.43

Yet how one comprehends these ends makes all the difference in grasping the stakes of the latent politics of amateurism, especially considering how limited cultural and economic opportunity can put any number of pressures on art’s capacity to garner currency—financial, social, or spiritual. Lacking deeper cultural context, we can end up preoccupied with claims of authenticity while obscuring alternative forms of agency and expression at work at the margins. Or, we find that amateurism is not exclusively ruled by a zero-sum game of cultural value (though the term still tempts binary valuations). Rather, amateurism’s rootedness in pleasure ties us back to process and to the agency of the maker, a fact that can take artistic production in numerous, sprawling directions that break down any sense of social and aesthetic hierarchies. Recordings can be both ethnographic and artful; paintings can serve everyday, religious purposes while taking the form of autonomous artworks.

The tension apparent in Gertrude Morgan’s amateurism derives from a sanctified piety that required her to be both in the world but not of it. In practical terms, it meant negotiating Holiness-Pentecostal doctrine in which spiritual labor was enacted within a market for music and art that someone like Borenstein opened up to her. As a missionary who never held a wage-paying job after the age of thirty-nine, when she left Georgia for New Orleans, she was not a member of the working or middle class for whom the rhythms of paid labor and leisure structured the week. Spiritual work and art were never neatly separated in Morgan’s practice, and heeding sanctified imperatives meant that her amateur status was defined as much by structural and social marginality as it was by a self-conscious choice to take up art as another extension of her beliefs. The center of gravity in her art remained at the edges of the mainstream economies of art (at least during her lifetime), because sanctification necessitated abstention from worldly pursuits. Therefore, inasmuch as Morgan’s practice resembled that of a Sunday painter, she was perhaps more accurately “Sunday’s painter,” so to speak: she cast visual art as one medium among others for channeling her holy devotion into professions of individual faith. These ventures carried simultaneously the risks between compromising one’s spiritual purity or shirking one’s sanctified obligations; Morgan negotiated these risks as she pursued the dignifying pleasures that came with affirming sanctified truths and her privileged relationship with the divine.

From this vantage, amateurism is not a self-evident status or label that describes skill alone. It is usefully recovered as a heuristic position that connects complex social and artistic practices to classifications of cultural activities captured by convenient, if not also blunt, terms like folk, popular, fine, and avant-garde art. With the sonic, textual, and visual records that Morgan left behind (many more than could be discussed here), we are left with the challenge of discerning the agency she exercised and imperatives guiding her in the social and cultural terrain defined by Jim Crow segregation and later reshaped by the Civil Rights Movement. This attention to black expressive practice is one kind of positive recovery that the discourse around amateurism has for art history that is both inclusive and emergent, arising against the conventions of the mainstream with the integrity of other traditions, values, and creative ethics.

July 3, 2019: An earlier version of this article cited a different work by Jason Berry in note 14.

Cite this article: Elaine Y. Yau, “The Love in Labor: Reconsidering Amateurism in Sister Gertrude Morgan’s Performances and Paintings,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1684.

Notes

I wish to thank Justin Wolff and Jessica Routhier for their guidance in bringing this essay in all its aspects to Panorama’s online platform. Special thanks also go to Caroline M. Riley and Imani Uzuri for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts.

- Rosemary Kent, “Sister Gertrude Morgan,” Interview 3, no. 9 (September 1973): 40. ↵

- Lucy Mulroney, Andy Warhol, Publisher (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 103–4. ↵

- Kent, “Sister Gertrude Morgan,” 40–41. Remaining quotations in the paragraph also derive from these pages. ↵

- I borrow this phrase from John Roberts, “The Amateur’s Retort,” Amateurs (San Francisco: CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, 2008), 22. ↵

- For more on institutional conventions and cooperative networks for artistic production, see Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1984. ↵

- Marci Kwon demonstrates that MoMA as a young institution could not sustain its embrace of folk and amateur art in the 1930s without threatening its commitment to modern art and emerging role as a bastion of sacralized culture. Through an analysis of the ARTnews decade-long column, “Amateur Notes,” that ran from May 1949 to March 1961, Kim Grant tracks a similar discursive shift from affirming amateurs as proto-modernists to denigrating amateur practice as hopelessly imitative. She also importantly highlights the gender biases against female artists within the periodical’s discourse of amateurism. Tellingly, as Lauren Kroiz shows in her work on John Steuart Curry, institutional affirmations of amateur artists in the years before World War II were more common in Regionalist contexts conscious of their difference relative to their non-agricultural, urban counterparts. See Marci Kwon, “Folk Surrealism,” in Sandra Zalman and Austin Porter, eds., MoMA: The First Twenty Years (forthcoming); Kim Grant, “‘Paint and Be Happy’: The Modern Artist and the Amateur Painter—A Question of Distinction,” The Journal of American Culture 34, no. 3 (2011): 289–303; and Lauren Kroiz, Cultivating Citizens: The Regional Work of Art in the New Deal Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), especially chapters 9–12. ↵

- John Ott, “Labored Stereotypes: Palmer Hayden’s The Janitor Who Paints,” American Art 22, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 102–15. ↵

- Lynne Cooke, “Boundary Trouble,” in Outliers and American Vanguard Art (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art in association with the University of Chicago Press), 4. ↵

- Leigh Eric Schmidt, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and American Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 7. While Schmidt’s study covers seventeenth- through early twentieth-centuries examples of religious audition, his analyses of Protestant formulations of hearing and use of sound technologies are relevant to later twentieth-century practices, including Morgan’s sanctified belief system. ↵

- Calling is but one aspect of sanctified practice. For more on Sanctified Church history, doctrine, and practice, see Cheryl Sanders, Saints in Exile: The Holiness-Pentecostal Experience in African American Religion and Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996); Anthea Butler, Women in the Church of God in Christ: Making a Sanctified World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); and Jerma A. Jackson, Singing In My Soul: Black Gospel Music in a Secular Age (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 8–26. For additional elaboration on calling in contemporary African American sanctified churches, see Glenn Hinson, Fire in My Bones: Transcendence and the Holy Spirit in African American Gospel (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 77–79, 212–18. ↵

- Though the bride has a long history within Christian traditions dating back to medieval European practice, Morgan’s adoption of white clothing as a manifestation of her state of grace was common among other African American Holiness-Pentecostal women in the twentieth century, especially during Sunday worship. As is common within vernacular religious practice, interpretations of doctrine can exist in as many variations as there are believers. I discuss the specifics of Morgan’s interracial imagery of her marriage to Christ in my current book project, which I understand as one model of gendering the Holy Spirit within sanctified practice. For other examples, see Wallace Best, “‘The Spirit of the Holy Ghost is a Male Spirit’: African American Preaching Women and the Paradoxes of Gender,” in R. Marie Griffith and Barbara Dianne Savage, eds., Women and Religion in the African Diaspora, Lived Religions series (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006): 101–27. ↵

- Jackson, Singing in My Soul, 17. Throughout this essay, I use Holiness, sanctified, and Pentecostal somewhat interchangeably to refer to the charismatic tradition informing Morgan’s art, though in discussions of doctrine and denominational history, these terms require further contextualization. ↵

- New Orleans-style jazz refers to the “hot” style associated with Bunk Johnson, Jelly Roll Morton, and Sidney Bechet that was central to midtwentieth-century debates about authenticity and preservation of jazz vis-à-vis the development of modern styles such as bebop. For overviews of these debates and the politics of jazz history, see Bruce Boyd Raeburn, New Orleans Style and the Writing of American Jazz History (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009) and Bernard Gendron, Steven B. Elworth, and Eric Lott’s essays in Krin Gabbard, ed., Jazz Among the Discourses (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995). ↵

- Jason Berry, City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 242–254. ↵

- According to R. Laurence Moore, “The very effort to create a demand for religion committed revivalism to a market logic and ultimately to market strategies.” Enfolded in such strategies were modern evangelical Christianity’s capacity to accommodate capitalist consumerism. R. Laurence Moore, Selling God: American Religion In the Marketplace of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 64. For examples of Christianity’s intersection with mass media in American culture, see Matthew Avery Sutton, Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), and Jonathan L. Walton, “The Preachers’ Blues: Religious Race Records and Claims of Authority on Wax,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 20, no. 2 (July 1, 2010): 205–32. ↵

- In addition to those residing in the Tulane University Hogan Jazz Archive, Morgan’s performances can be found on Let’s Make A Record (True Believer Records, LP, 1971; rereleased by Preservation Hall Recordings, compact disc, 2004); New Orleans Jazz and Gospel: The Larry Borenstein Collection (504 Records, 504CD45); and Made In New Orleans: Preservation Hall (Preservation Hall Recordings, 2007). ↵

- All three expressions define the way Morgan describes her conversion in “Some History of Life,” undated and unsigned manuscript, Sacha Borenstein Clay Collection. ↵

- Mae G. Henderson, Speaking in Tongues and Dancing Diaspora: Black Women Writing and Performing, Race and American Culture series (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014): 59–75. Emphasis original, 62. ↵

- Henderson, Speaking in Tongues, 60. ↵

- Henderson, Speaking in Tongues, 74. In leaning on Henderson’s adaptation of a “spiritual rite and cultural practice as a critical praxis and theoretical trope,” I do not wish to overlook the likelihood that Morgan experienced glossolalia and negotiated similar positions of identity and difference. Whereas glossolalia is viewed as a spiritual gift in sanctified belief—and has been used to distinguish different levels of spiritual election and emphasizes unknowable aspects of divine prerogatives—my essay analyzes Morgan’s musical performance as a black woman’s social and expressive practice. It is informed by Henderson and Daphne A. Brooks’s approach to black feminist noise as discussed in “Afro-Sonic Feminist Praxis: Nina Simone and Adrienne Kennedy in High Fidelity,” in Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita Gonzalez, eds., Black Performance Theory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014): 204–22. ↵

- Alexander G. Weheliye restates that this seemingly untainted sonic experience is not unmediated but “represents . . . an originary fabrication of the source itself.” Alexander G. Weheliye, Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 119. ↵

- The largest sanctified denomination was the Church of God in Christ, organized in 1907, which already rivaled more established, mainline denominations by the 1940s. See Jackson, Singing in My Soul, 16–18, 34–35. ↵

- As Roland Barthes has famously proposed, “the grain” is that which conjoins music to the materiality body that generates it: “the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs.” The concept reframes music as an experience inclusive of the embodied individuality of the performer. Barthes, “The Grain of the Voice,” in Image, Music Text, trans. Stephen Heath (London: Fontana Press, 1977), 188. ↵

- For discussions of authenticity and folk cultures, see Regina Bendix, In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997). ↵

- As E. Patrick Johnson argues, performance has the potential to oppose essentialist constructions of black culture by understanding “the relationship between the body and discourse as a complex, dynamic, intricate web of signification and meanings that are simultaneously experienced as real and imaginatively produced.” See E. Patrick Johnson, Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 207. ↵

- The Gospel Keys, “You’ve Got to Move,” The Asch Recordings, 1939 to 1947—Volume 1: Blues Gospel and Jazz (Smithsonian Folkways Records, FW00AA1, 1966). ↵

- The term “broadcast” derived its meaning from its agricultural concept of “broadcast seeding” that construed sonic reproduction as a dispersal of sound over space and time, rather than through space alone. Broadcasting did not imply sound as an attenuated phenomenon but of localized generativity that occurred in moments of hearing. This model of sonic transmission accords closely with Morgan’s evangelistic approach that wielded song, preaching, and testimony within a sonic battleground for the unsaved against incursion of the devil (Lucifer) and the lies he presumably told. Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 205–6. ↵

- See William A. Fagaly, Tools of Her Ministry: The Art of Sister Gertrude Morgan (New York: American Folk Art Museum and Rizzoli International Publications, 2004), 73n62. ↵

- Lynn Abbott, I Got Two Wings: Incidents and Anecdotes of the Two-Winged Preacher and Electric Guitar Evangelist Elder Utah Smith (Montgomery, AL: CaseQuarter, 2008), 10–11. ↵

- Further analysis is required to assess the degree to which gender played a role in Smith’s local prominence, for despite the Holy Spirit’s power to call and anoint men and women alike as church leaders, some sanctified denominations absorbed mainstream gender proscriptions against women serving as preachers. ↵

- Jackson, Singing in My Soul, 92–93. ↵

- As Jackson argues, Tharpe’s career tells the story of black talent increasingly brought under control of a secular entertainment industry and illustrates the risks that confronted gospel singers who sought to balance sacred values in a commercial realm. See Jackson, Singing in My Soul, 77–142. ↵

- To my knowledge, there is no comprehensive study of Borenstein’s dealings with visual artists. Judging from historical photographs and examples of work by artists sold by Associated Artists Gallery, the dominant types of art available at the gallery were portraits or landscapes. For example, see the portfolio of drawings by Andrew Lang, Jamming at Wit’s End (undated); Xavier de Callatay’s Sourires du Vieux Carre: 10 Dessins a la Plume (1956?); and Noel Rockmore’s Preservation Hall Portraits (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1968). ↵

- Drawn from Ezekiel 37, this story describes the exiled prophet’s vision of God’s spirit commanding him to prophesy over bones and restore them to life. The text was popularized as a spiritual that the Fisk Jubilee Singers, among other groups, performed under the title “Dry Bones.” It also appears as part of the repertoire for African American preachers, which were recorded and marketed specifically to black audiences beginning in the 1920s. These “race records” signal, to varying degrees, the popularity that both record companies and audiences accorded them. Examples mentioned here can be heard on Fisk Jubilee Singers Volume 3 (1924–1940) (Document Records, 1997) and Rev. J.M. Gates Volume 4 (1926) (Document Records, 1996). For more on “race” records, see Paul Oliver, Songsters and Saints: Vocal Traditions on Race Records (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1984) and Walton, “The Preachers’ Blues,” 205–32. ↵

- Matthew 11:28–30, a passage Morgan cited in at least four different artworks, secures this re-signification of rest as a spiritually active process. It conveys Christ’s teaching that Christian devotion is the antidote for world-weariness: “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn of me . . . and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” Morgan invokes this passage in REV. 8 Woe Woe Woe (undated; location unknown), Let Us All Run to Jesus He’s the One (undated; Gitter-Yelen Collection), The Righteous and the Wicked Prov. 15.28 (undated; New Orleans Museum of Art), and Ephesians 1:1.2.3.4.5.6{…} (undated; New Orleans Museum of Art). ↵

- For example, see Sister Gertrude in Her Prayer Room (undated; New Orleans Museum of Art). ↵

- As Glenn Hinson documents, spontaneity is a key characteristic for discerning the true movement of the Holy Spirit in African American Gospel communities. See Glenn Hinson, Fire in My Bones, 256. ↵

- References to passages in Revelation are inscribed on the artwork’s verso. For a full transcription of the remaining verses, see Fagaly, Tools of Her Ministry, 21. “Flash of the spirit” is Robert Farris Thompson’s influential formulation of diasporic black aesthetic expression. See Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983). ↵

- Ernst Gombrich, The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art, The Wrightsman Lectures delivered under the auspices of the New York University Institute of Fine Arts (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979), 82 and 116. ↵

- Zora Neale Hurston, “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” in Nancy Cunard, ed., Negro: An Anthology (New York: Negro Universities Press, 1934) and reprinted in Zora Neale Hurston, “Sweat,” edited by Cheryl A. Wall (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 56. ↵

- For Morgan, picturing a marriage to a racially white Christ braided religious, visual, and affective threads together. I discuss these aspects in “Sister Gertrude Morgan and the Materials of Visionary Art,” James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill, eds., Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017): 113–24. ↵

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art + Textile Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 5–6, 33, and Byron Kim, as quoted in “Artists on Diaries: Notes from a Sunday Painter,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution website (blog), March 27, 2015, https://www.aaa.si.edu/blog/2015/03/artists-on-diaries-notes-from-sunday-painter. ↵

- Bryan-Wilson, Fray, 33. ↵

About the Author(s): Elaine Y. Yau is the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, Berkeley