Beyond Land Acknowledgments

Founded in 1870, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, stands on the historic homelands of the Massachusett people, a site which has long served as a place of meeting and exchange among different nations. As a museum, we acknowledge the long history of the land we occupy today and seek ways to make Indigenous narratives more prominent in our galleries and programming.

—Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, land acknowledgment

How do museum professionals begin to indigenize an art museum shaped by European colonial legacies? As Indigenous and Latinx colleagues at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, we created a working group to think through this question. The title of this essay, “Beyond Land Acknowledgments,” demonstrates our commitment to exploring ways that Euro-American museums can center Indigenous people and their values.1 We are concerned with making land acknowledgments actionable, a starting point for building sustainable relationships. What does it mean to have a Native North American Art gallery, and what impact can such a space have (fig. 1)? What do we do with famous works of art by white artists that erase or stereotype Indigenous peoples? How can we amplify the voices of living Native artists throughout the museum and across our communities?

In order to think “beyond” land acknowledgments, we should first understand what constitutes a land acknowledgment and where it comes from. Many Indigenous communities begin ceremonies by thanking and acknowledging their ancestors and lands, beings and places that are deeply connected and often share a mutual moment of origin. In current practice, a land acknowledgment is a short oral statement given at the start of an event or meeting or a text posted at the entryway to an institution, which recognizes the connection of the place to its original people. However, without further efforts to create relationships between non-Native institutions and Indigenous communities, a land acknowledgment can ring hollow or even simply be a painful reminder of stolen land. Indigenous peoples have always called for the return of land and resources, but activists, especially since the Standing Rock Water Protection movement of 2016–17, have brought renewed urgency to these reclamations. While we have seen a dramatic rise in the number of institutional leaders implementing land acknowledgments, others remain fearful of making such statements, perhaps understanding that this step can and should lead to more radical actions. When we say “beyond land acknowledgments,” we understand both their necessity and their limitations, and through our roles as museum workers, we strive to confront the colonial legacies of institutions and make space for our local Indigenous communities and Native peoples more broadly so that they may feel seen and be concretely acknowledged.

From 2020 to 2021, we worked with colleagues across the MFA to improve how we care for, collect, display, and steward Indigenous art. Reinstallations in our permanent-collection galleries; temporary exhibitions, including Garden for Boston; collaborative interpretation initiatives, like Translating American Stories; and COVID-era digital projects represent different strategies for moving beyond land acknowledgments. By sharing these experiences, we continue to think about ways to better foster the study of Indigenous art at our institution, across time and space.

Layla Bermeo, Kristin & Roger Servison Curator of Paintings

While curating Collecting Stories: Native American Art (2018), a small exhibition that asked how works of Indigenous art came to the MFA, Dennis Carr, then the Carolyn and Peter Lunch Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture, and I attempted to write the museum’s first land acknowledgment.2 This project, which was supported by a Henry Luce Foundation grant, focused on understudied permanent collections and created opportunities to develop models for presenting works by Native artists that departed from the ethnographic style of our Native North American Art gallery. As we considered incorporating multiple labels and videos, displaying objects without vitrines, and engaging Indigenous knowledge keepers, we were haunted by the disconnect between the works in our collection and the location of our museum. Although the MFA has collected Native art since the 1870s, works by local Indigenous artists, such as those from the Massachusett, Wampanoag, and Nipmuc communities, are among the least visible in our galleries. Writing a land acknowledgment offered a way to raise awareness, as well as questions, about the definitions of who and what is “local”—questions that were immediately contested by our different Native consultants (which is one of the reasons why our official statement remains under construction). Now, as we continue to confront institutional erasures and collaborate with Indigenous experts to better care for the Native art in our collection, we still regularly feel dissatisfaction with imperfect solutions and the stinging frustration of disappointing the people we hope to welcome to the MFA. Museums, particularly “encyclopedic” institutions, have long colonial histories and entrenched identities that a single person or initiative cannot undo; the undoing, or remaking, of how museums function is a process of trying, failing, responding, and growing.

The single-gallery show Collecting Stories made space for many different voices, including a public comment wall. Visitors used it to tell us how much they hated the exhibition and how it was pathetically small, filled with stolen objects, and recentered white collectors. I carry this feedback with me, knowing that, although Collecting Stories was far from perfect, it was an experiment. In 2018, there were no Native people on the MFA’s curatorial staff. Consulting artists and scholars provided meaningful contributions. Contemporary artists D. Y. Begay (Diné) and Maria Hupfield (Anishinaabek of Wasauksing First Nation) contributed interpretations and new works of art. We also organized a panel to review exhibition texts, including those focused on stereotypical representations of Native people by white artists. While editing the document, art historian Jami Powell (Osage) added a Track Changes comment about our tabletop version of Cyrus Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit (1908) that was so powerful, we made it into a label:

Like the works of many other European and American artists of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Dallin’s sculpture narrates a specific story about the decline, loss, and extinction of American Indian peoples. Although I can appreciate the aesthetic beauty of Dallin’s work, I cannot reconcile it with the inaccurate message that it continues to convey to broader publics, particularly as the most visible representation of American Indians at the MFA.

Powell’s insights offered a critical reading of Appeal to the Great Spirit, the sculpture of a lone Native figure on horseback with a feathered headdress and outstretched arms. The iconic full-size version has been installed outside the MFA’s main entrance since 1912. Some among the museum’s staff worried that Powell’s statement would confuse the public; in response to this concern, we included the heading “Another Perspective” on the label. Four years later, in 2022, we would not preface an expert’s words with such an anxious disclaimer.

Today, our galleries still include historical Zuni Pueblo ceramics, Wyandotte moccasins, and other works of Native art of the type featured in Collecting Stories. Even as we write new labels, place these works in conversation with different objects, display some more prominently, and remove others from view, I sit with the questions that Collecting Stories raised about how best to honor historical works of Indigenous art when there are questions (that do not apply to contemporary Native art) about whether these objects should be in a museum at all. The goals of visibility—of securing the place of Indigenous artists within American art history—often conflict with the ethics of collecting, even when objects were not explicitly stolen or coerced from their makers. The great majority of the historical Native art in our collection has not been given to us by Native people or purchased from Native people; instead, most of these objects have passed from the hands of one white collector to the next. In order to create truly Indigenous spaces within museums, I think we must center consent, rather than just consultation, with Native people for the collecting, display, and interpretation of their art.

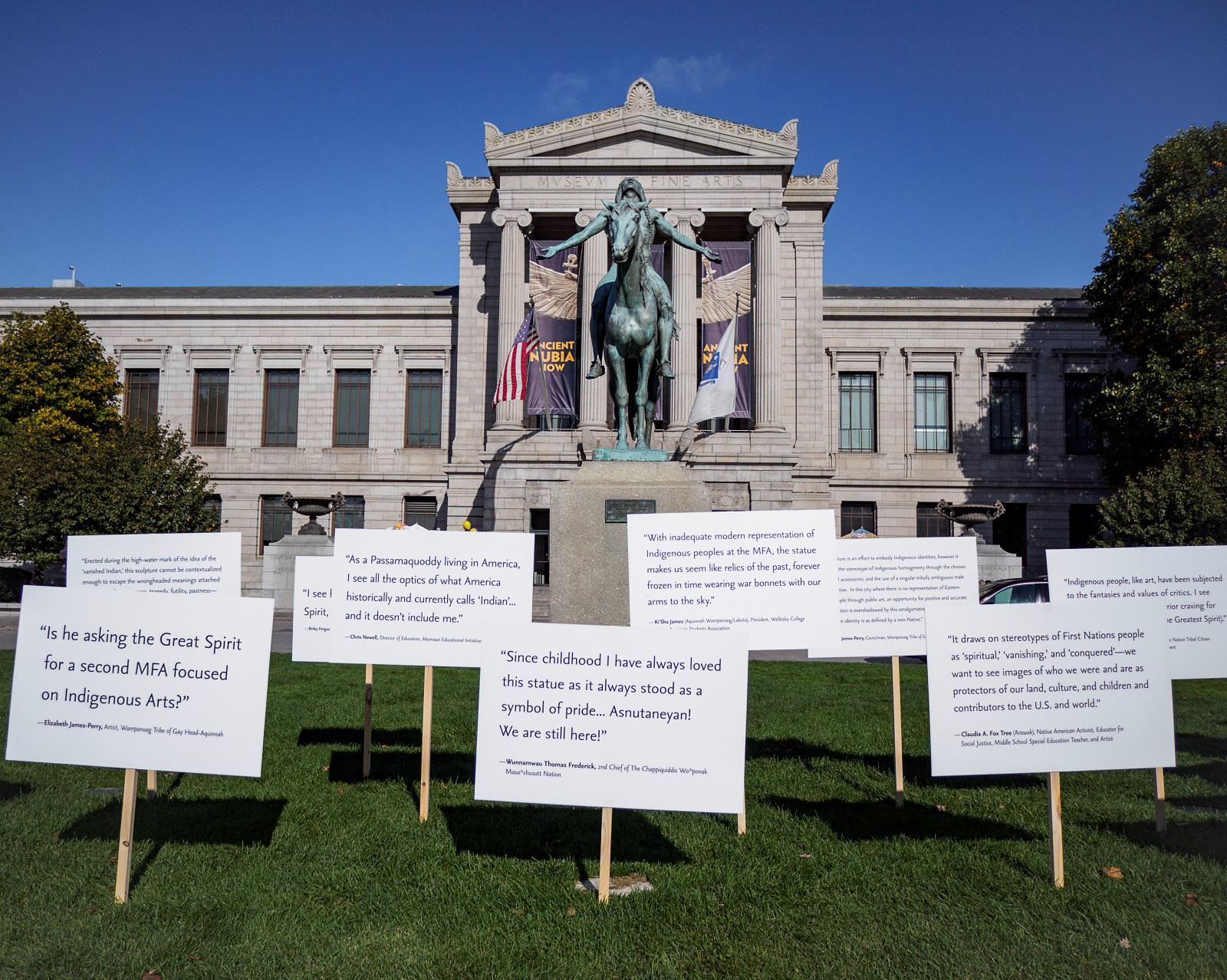

When we planned the MFA’s first celebration of Indigenous Peoples’ Day in 2019, members of local Native organizations would not partner with us unless we agreed to address the Appeal to the Great Spirit sculpture at the museum’s entrance. Although it is beloved by some, the sculpture presents a painful stereotype from which a white artist profited, an embodiment of the vanishing-race myth that situates Indigenous peoples as defeated by, rather than part of, modern life. Debates about monuments animated our internal discussions about how we interpret Appeal to the Great Spirit, which is both just another object in the Art of the Americas collection and a giant public sculpture that people see whether or not they choose to enter our building. We invited about twenty-five Indigenous artists, scholars, and activists, as well as some non-Native experts on Dallin, to answer the question, “What do you see when you look at this sculpture?” Their responses were printed on signs and posted around the sculpture on Indigenous Peoples’ Day (fig. 2). Visitors could also respond to the question. One person told us, “I see a proud and defiant man ready to fight for his people and his culture”; another wrote, “It tells me that the museum isn’t for Native people like me, but for white people and their false impressions of reality.” Appeal to the Great Spirit has always elicited mixed responses among Native and non-Native people alike. But critical readings, such as the powerful words of Joseph Zordan (Anishinaabe), who later wrote an essay on the topic,3 have taught us something that all museum workers should know: if we truly believe in the power of art, we also have to believe that it has the power to hurt people.

When discussing problematic works of historical art, I often hear museum professionals and visitors explain away discomfort by insisting that “we” now see works like Appeal to the Great Spirit differently from how “they” viewed them in the past. As with so many stereotypical images, this object likely hurt people who were never asked how they felt about it, then as well as now. We found that almost everyone had something to say about the sculpture, as they probably did around 1910 when it was made. These responses shaped our new label for Appeal to the Great Spirit—the first in over one hundred years of display—and formed the core of our online resources dedicated to the work.4 I still wonder, though: does anyone actually believe that any measure of “interpretation” can compete with the overwhelming visual power of a monument or sculpture of this size? The great potential of the Garden for Boston project, which is discussed later in this essay, is that it moves beyond “context” and transforms physical space.

Like the Indigenous Peoples’ Day intervention, Translating American Stories also focused on interpretation and collaboration. The first initiative to bring multilingual labels into our permanent collection galleries, it was born early in the COVID-19 pandemic, when many began to work from home. How could we make changes to our galleries and welcome new audiences if we could not physically move objects? We hoped that labels in different languages might help tell new stories about old things and confront some erasures in early American art history. The Sons of Liberty Bowl, for example, is deeply tied to the patriotic history of the United States, made in Boston by Paul Revere himself around 1768, but where did the silver come from to make it (fig. 3)? It was probably mined in Mexico, meaning that this object carries a Latin American history, and Indigenous hands touched the raw materials before Revere modeled it into the shape of a Chinese vessel.

And what if, instead of focusing our label on Isaac Winslow, the subject of a 1748 Robert Feke portrait, we asked Wabanaki people to consider the landscape of Maine to which Winslow points (fig. 4)? From the beginning, we knew we wanted to represent languages commonly spoken in Boston after English—Spanish, Haitian Creole, Brazilian Portuguese, and Mandarin Chinese—to revive the international journeys objects took on their way to us. We also knew we wanted to include an Indigenous language to acknowledge the long histories of this region, and we were honored to work with elder and language teacher Roger Paul (Passamaquoddy/ Wolastoqey) to reorient Feke’s landscape in relation to Wabanaki homelands. Paul and other contributors, who included bilingual MFA staff members and no professional translators, did not simply translate the curators’ words but actively collaborated on the creation of new content. Their skills and vision enabled us to open works of art to new narratives that might resonate with people who have never seen themselves in our galleries, even though our museum is on their land.

Tess Lukey, Former Curatorial Research Associate

I have lived in New England my whole life. I come from this land; my ancestors came from this land. I am a citizen of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah. Since I was in elementary school, I knew that I belonged to a Native community. It took my family more than a decade to collect documents, apply to become members, and receive tribal citizenship. All the while, I was learning and shaping my identity as a Native woman. I remember attending my first youth group retreat on Noepe (Martha’s Vineyard) and being greeted by our former tribal chairman, Tobias Vanderhoop. I told him it was my first time on the island, and he said, “Welcome home!” When I think about his words, they still bring tears to my eyes. I have come a long way from that day and can now proudly say in my language, Nuwtômâs Aquanahunut! I am Aquinnah Wampanoag.

Growing up and living several hours from Aquinnah, I have always looked for places that I could call a home away from home. I found solace in the MFA. I am an artist, and art is inherently tied to my identity, as is being Native. I remember when I first visited the newly opened Art of the Americas wing in 2010. I had heard that the Native American gallery was on the ground level, in what felt like the building’s basement. Although this placement was disappointing, I still was excited to enter a space with works made by artists who, in some ways, looked and thought like me. I wondered if there was Native American art elsewhere at the MFA. Sadly, there was not.

In January 2020, I joined the MFA’s Art of the Americas department as a Curatorial Research Associate. Though this position is not dedicated to Native American art, I was the only one in the department with expertise in this area, and so I offered help whenever I could. I led numerous changes throughout the wing in an effort to bring Native art out of the basement and to integrate Indigenous works and voices into different narratives and time periods. One of the first events in which I participated was our celebration of the museum’s 150th anniversary. Staff members and employees had the opportunity to give short talks about works in the collection. I spoke about a pair of moccasins in the Native North American gallery from a now-unknown Woodlands community. It was important to me to speak about a Native work of art and bring people down to this space, a space often forgotten, to learn about an object that was from my own territory. I proudly told stories of creation, tradition, and trade, all the while wearing my own, newly made moccasins and leggings. This event kickstarted my efforts to make local eastern Woodlands communities more present in the MFA galleries, physically and digitally.

After this presentation, Layla suggested that I create a digital project for the MFA’s website about works from Woodlands communities that were on display at the time. I knew that our collection did not include any works by Wampanoag or other people native to Massachusetts, but our slideshow “Of This Land: Native American Woodlands Art” was the start of better representing communities often left out of the histories of New England.5 This increased visibility led to other opportunities at the museum, such as the invitation to lead a workshop for Boston-area schoolteachers. Titled “What is American?: Native American Art,” this workshop offered a range of contexts for talking to students about these works and emphasized the importance of including Native American communities and cultures from New England in our local educational systems.6

But my colleagues and I wanted more than just a digital presence for these materials. We developed a series of what I call “interventions” in galleries throughout the Art of the Americas wing. In gallery 133, a space that has prominently featured early nineteenth-century portraits of George Washington, visitors now encounter a case of objects that seeks to bring New England Native communities into this story about images of leadership and diplomatic power (fig. 5). The text panel “Symbols of Power, Objects of Exchange” explains how artists within Native American communities, like their European counterparts, created objects that represent status. A decorated war club and the presentation sword, for example, were both intended to proclaim the authority of their owners. Such comparisons can begin to shift narratives about early northeastern America, too often characterized as an empty wilderness before Europeans arrived. Works of art from the Anishinaabe, Lenape, and other Indigenous nations tell very different stories about these lands that their descendants still call home. Certain objects carried meaning in both Native and non-Native cultures. Wampum belts and commemorative medals, for instance, were exchanged as diplomatic gifts and tokens of friendship and respect between the constellation of nations—both Indigenous and settler.

A wampum belt by Elizabeth James-Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag, b. 1973) makes this installation especially important, because it is the MFA’s first acquisition of a work by a living artist from a local Native community in Massachusetts. The Weatchamin belt is also the first wampum work by a woman Wampanoag artist in the collection (fig. 6). Weatchamin, or corn, is an important crop tied to the origin stories of northeastern Native communities. Wampum belts, made from Quahog clam shells and plant fibers, were used to commemorate important events or to signify treaty agreements between Native communities and European colonists. James-Perry created this wampum belt to commemorate her installation Raven Reshapes Boston, held at the MFA in 2021. For this project, James-Perry planted a field of corn at the museum entrance to acknowledge and honor Boston’s Indigenous history.

The entrance to the Art of the Americas wing also has a new text panel greeting visitors, created collaboratively with colleagues in the department. In it we ask, “What do we mean by ‘Art of the Americas’? And who do we describe as an American artist?” The text expresses our commitment to presenting creative voices from across the Americas, including those historically underrepresented in our galleries, among them women, Indigenous artists, Black artists, artists of color, and self-taught or folk artists. Alongside this statement hang two paintings by the late T. C. Cannon (Kiowa and Caddo, 1945–1978) (fig. 7). As a painter, poet, and musician of the Kiowa tribe with Caddo descent, Cannon overturned deeply rooted cultural conventions to center his Native American subjects, literally and figuratively. He drew on a range of sources—historic photographs of tribal leaders, eighteenth-century British and American portraits, the bold and unexpected color combinations of Pop artists like Andy Warhol—and his art challenged the erasure of Indigenous people from national histories and landscapes. Although much of our collection remains dedicated to white male artists, the Cannon paintings at the front door represent our aspirations to create a multifaceted approach to presenting the arts of the Americas.

Most recently, we collaborated on a project that moves beyond the museum’s walls. Garden for Boston brings together two projects by local artists Ekua Holmes (African American, b. 1955) and James-Perry.7 Together, they transformed the MFA’s front lawn into blooming fields of sunflowers and corn, plants long associated with resilience and connections between people and the natural world (figs. 8–10). Holmes and James-Perry designed the gardens and planted them with the help of volunteers and community gardeners from across Boston. Their installations are radical departures from the museum’s imposing architecture and Dallin’s monumental Appeal to the Great Spirit. Welcoming visitors, the gardens invite new focus on the history of the land the museum occupies. The project included two iterations of artist-designed billboards near the gardens.8

Raven Reshapes Boston is a reference to the eastern Native story about the traditional knowledge keeper Raven. Raven brought corn to this region for Native women to grow and sustain their families. In the spirit of this being, the garden is meant to welcome, inspire, and provoke discussion. It serves as a lively northeastern Native counterpoint to the controversial Appeal to the Great Spirit sculpture. The plants grew high throughout the season and matured as we collectively enjoyed the space and anticipated the harvest and distribution. The durable and uniquely colored pale-yellow dried corn husks, grasses, and corn leaves continue to sustain us even after the garden returns to the earth. As James-Perry says, corn is tall, fluid, and feminine. The slightly mounded shape of the garden and its variety of natural colors and textures soften the squared edges of the museum’s lawn: broad-leafed corn, shorter fine sedge grasses, and cranberry-bean plants. Outlined in the shape of a horseshoe crab and bordered with a white crushed-oyster-shell border, this planting is connected to Wampanoag coastal identities. It recalls rich sea harvests and coastal feasts—reminders of the shell middens once ubiquitous in what is now a concrete cityscape. The garden is a reclamation of Boston as Indigenous land.

Raven Reshapes Boston is in conversation with Holmes’s Radiant Community, an experimental installation of sunflowers. For Holmes, creator of the Roxbury Sunflower Project, sunflowers represent resilience, self-determination, and the ability for a community to evolve and emerge while staying grounded in history and traditions.9 This combined project is the most visible reclamation of the land of Boston for the communities it represents and shelters. Like the other gallery changes, it is our way of welcoming visitors to come and stay for a while.

Marina Tyquiengco, Ellyn McColgan Assistant Curator of Native American Art

Håfa Adai todos! Na’an hu si Marina Tyquiengco. Greetings, my name is Marina Tyquiengco. I am very happy to introduce myself in CHamoru. I am an Indigenous person from Guåhan (known as Guam), one who is in the process of learning my heritage language.10 My mother’s family is from northern Europe by way of northern California so, like many, I come from settlers and Indigenous people. I first studied CHamoru as a child on Guåhan. But later, growing up mostly in northern Virginia without my CHamoru family nearby, I had no one to teach me more about the language. Today, I am able to learn it virtually, many thousands of miles from Guåhan, thanks to generations of CHamoru scholars and elders who preserved the language throughout multiple colonial regimes.

Since September 2021, I have worked at the MFA as the inaugural curator of Native American art, a role that I am immensely honored to hold. The gallery of Native North American art has changed little since it opened in 2010. Yet the MFA remains distinct among many museums by designating a gallery to Native American art and housing it within the American art department. The Native North American art collection contains around one thousand objects, ranging in date from the ancient to the contemporary periods. Historically, the MFA has not collected the work of Native American artists from the New England region. Moving forward, I seek to emphasize the living nature of many of these traditions and incorporate the voices of living artists into all forms of interpretation. A major priority is to highlight the art of New England and northeastern communities and approach the belongings in our care through perspectives from these communities.

Before becoming curator of Native American art, I was a curatorial assistant in the museum’s Department of Contemporary Art for over a year. The department focuses on art created after 1955. Since its charge is informed by temporality, not by place or type of object, its curators collaborate and intersect with many MFA departments that collect art made after 1955, such as Prints and Drawings and Textile and Fashion Arts. Layla quickly brought me into conversation with Tess. These women have made my work infinitely better. Opportunities to commune and collaborate with like-minded people are, unfortunately, something to which many professionals who identify as Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) do not have access, particularly in museum spaces. Our shared interest in Native American and Indigenous art did much to sustain me as I initially worked on unrelated projects.

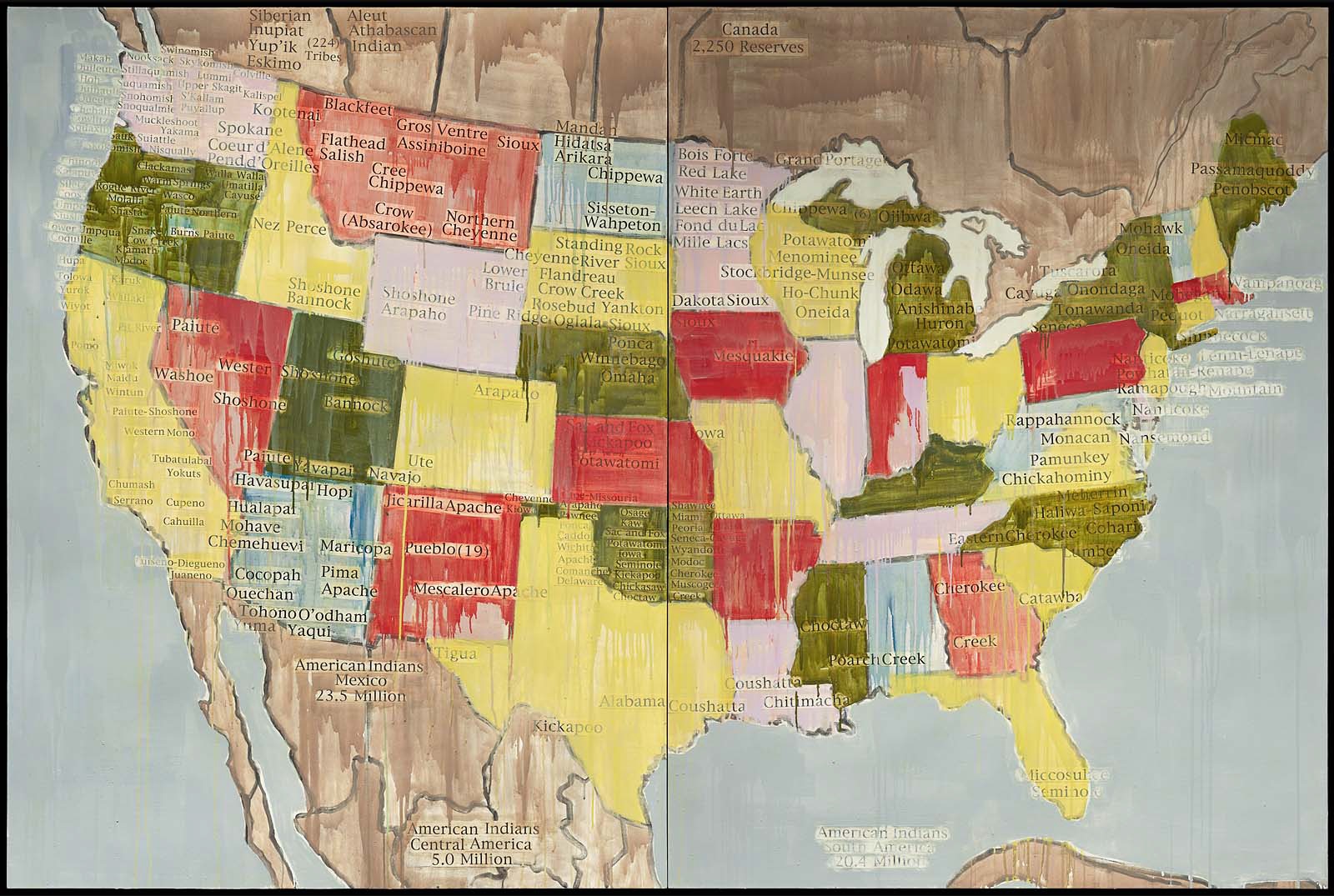

Our first collaboration was a blog post in September 2020, part of Art for This Moment, a new online initiative driven by the limitations of COVID-19. The post explored how the esteemed Confederated Salish and Kootenai artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s painting from 2000, Tribal Map, could speak to the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on Native communities (fig. 11).11 Acquired before I came to the museum, Tribal Map is a massive multicolored diptych painting and collage of a map of the contiguous United States. In it, state names have been replaced or overwhelmed by names of Native nations and tribes with more than three hundred members. In 2018, Layla had worked on the acquisition of this work, the first painting by Smith to enter the collection. Tess brought knowledge of the artist and added the perspective of her own community’s response to the coronavirus. We collaborated, building on my initial idea to connect this painting from the year 2000 with the present COVID-19 pandemic, occurring decades later.12 Maps were a familiar infographic in attempts to chart the spread of the coronavirus in newspapers, magazines, and on social media, and the spread of the virus underscored the country’s interconnection. It has also been interesting to note, more recently, that once COVID-19 vaccinations became available, some of the states with the best vaccination rates owe that statistic to their Native communities, whose health departments worked tirelessly to spread correct information and vaccinate people.

Epidemics and pandemics have long plagued Native communities. In exploring the response to the extremely adverse effects of COVID-19 on Native communities, we found that the creative problem–solving skills of these communities were very apparent. In our 2020 post, we referenced a youth program from Smith’s own community that spread COVID awareness through song.13 We concluded our blog post with two questions: “Has your perception of maps and other infographics changed in the time of COVID-19? As we imagine this country as a collective whole, rather than individual states, how might we map out a more equitable future with respect to racial, ethnic, and resource disparities?”

While these questions remain unanswered, we continued to think about them and the theme of humanizing nearly unimaginable things, like the vast number of people who succumbed to the virus and its variants. Further, Layla, Tess, and I realize that our ambitions to change the field of art history and develop exhibitions that attract new audiences to the museum involve reworking relationships inside the museum, building trust with potential visitors, and considering the wide-ranging effects of human dominance on the nonhuman world.

I kept these concerns in mind while I worked on New Light: Encounters and Connections, which opened on July 3, 2021, and I continued thinking about Smith’s important painting. The exhibition was organized as an interdepartmental collaboration that took place largely over Zoom.14 The central concept was that single objects can change the stories that we tell, writ large. Complex, untold, or insufficiently shared stories are revealed through pairings of new acquisitions from the Department of Contemporary Art with works from other MFA collections, such as the Arts of Asia.

A highlight is the pairing of Smith’s Tribal Map with John Willis’s photos documenting protest efforts to stop the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Reservation (fig. 12). Karen Haas, the Lane Senior Curator of Photography, proposed this juxtaposition, and I worked with her to create the interpretative materials. The Water Protection Effort at Standing Rock was the largest collective Indigenous protest in US history, including Native people from many tribes and nations as well as allies.15 Willis is a non-Native photographer with long connections to the Rosebud Indian Reservation. He published a book of his images of the protests he participated in and his trips to and from Standing Rock, which spans both North and South Dakota.16 All six works from Willis’s series are in the MFA’s permanent collection and are presented in New Light: Encounters and Connections. The photograph Indigenous women leading frontline action to location where the Dakota Access Pipeline is being buried in the ground speaks to Tribal Map because it reflects the importance of women as leading the water-protection efforts by capturing a line of mostly women standing together with protest signs behind a row of empty cups and two jars of water.17 The photograph’s even longer full title is a story about when Indigenous women deescalated a tense situation and invited the police to share in their protest and pray with them: a beautiful and hopeful moment. This representation relates to Tribal Map, which just as beautifully insists upon the continued presence and land stewardship of Indigenous peoples in the Americas.

The curatorial team for the exhibition solicited artist quotes for the interpretive materials. Smith wrote a statement on her piece that is particularly powerful. With her permission, I share it below because it allows viewers to understand the work from the artist’s perspective:

This is a living map of tribes that exist today. There are no extinct tribes on this map. There are 562 Federally Recognized tribes on this map and 63 State Recognized tribes. There are several hundred tribes with applications waiting for either congressional members of a state or the congress of the United States to recognize them, meaning to authenticate them, allowing them to become real Indians. If you think about it, this means that a congress of elderly white men have the power to vote on whether a Native person can call themselves a Native American. Whereas the congressional members are allowed to identify themselves as German, Irish or another European origin. The reasons are clear. Congress does not want to add more Natives to the rolls because Indians could then apply for IHS, the Indian Health Service, as well as other Native American services through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Often the services at IHS or the BIA are very poor and not as helpful as social services in the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare that serves all other people. They are chopping down trees, killing bears and other wildlife, this doesn’t bode well for Native Americans. Native Americans still live under a colonial system.18

Writing here twenty years after the piece’s creation, Smith argues for the continuing need to recognize the presence of Native people in the enduring situation of colonialism. The resilience of communities and the coloniality of the system in which they live can both be true. Smith brings up an important point: many of the things promised to Native people by the government, including health care and other forms of community support, have not been fulfilled. In my role, I seek to emphasize Indigenous knowledge and worldviews through collaborations with Native thought leaders from this region.

This discussion lays out some of the museum’s ongoing efforts to move beyond acknowledgment toward practical collaboration. Layla’s work with community-based translation and interpretation demonstrates a new approach to recognizing the historical and contemporary diversity of Boston and beyond. Tess’s strong call to highlight Native New England and think about the lived experiences of Native American visitors demonstrates how the museum can address the Native land itself that it occupies. New collaborations and lasting change take time. Our work is just getting started. To our collaborators who share our efforts, I say: Muchas gracias! Kutâputush! Si Yu’us ma’åse’! Thank you!

Cite this article: Marina Tyquiengco, Layla Bermeo, and Tess Lukey, “Beyond Land Acknowledgments,” in “Art History and the Local,” In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13208.

PDF: Tyquiengco, Bermeo, and Lukey, Beyond Land Acknowledgments

Notes

- An earlier version of this roundtable conversation was presented and recorded in June 2021 for the virtual annual meeting of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA). ↵

- Museum of Fine Arts Boston, “Collecting Stories: Native American Art,” accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.mfa.org/exhibitions/collecting-stories-native-american-art. ↵

- Joseph Zordan, “Appeal to the Great Spirit,” Art for This Moment, July 6, 2020, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, https://www.mfa.org/article/2020/appeal-to-the-great-spirit. ↵

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “Cyrus Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit,” accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.mfa.org/collections/art-americas/appeal-to-the-great-spirit. ↵

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “Of This Land: Native American Woodlands Art,” accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.mfa.org/collections/art-americas/of-this-land. ↵

- Tess Lukey, “What is American?: Native American Art,” June 10, 2021, Educator Workshop, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, video, 89:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQpW2vvW-R0. ↵

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “Garden for Boston,” accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.mfa.org/exhibition/garden-for-boston. ↵

- For more on these billboards, see Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “Garden for Boston.” ↵

- See Now + There, “Roxbury Sunflower Project,” accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.nowandthere.org/roxburysunflower. ↵

- Chamorros living in the Commonwealth of Northern Marianas Islands prefer the spelling “Chamorro.” The spelling of Chamorro as “CHamoru” is specifically tied to Guam, based on a 2018 declaration by the governor. See “Commission: CHamoru, not Chamorro; Guam’s female governor is maga’håga,” Guam Pacific Daily News, November 30, 2018, https://www.postguam.com/news/local/commission-chamoru-not-chamorro-guam-s-female-governor-is-maga/article_045523dc-f3b9-11e8-9b53-5ba21e8bb30a.html. ↵

- Marina Tyquiengco, Tess Lukey, and Layla Bermeo, “Tribal Map,” Art for This Moment, September 8, 2020, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, https://www.mfa.org/article/2020/tribal-map. ↵

- Smith also provided an emailed statement about the piece for the exhibition New Light: Encounters and Connections in January 2020. ↵

- Although it is no longer active on their website, information about this program was included on the Tribal Health website of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes: https://cskthealth.org. ↵

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “New Light: Encounters and Connections,” accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.mfa.org/exhibition/new-light-encounters-and-connections. ↵

- See Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future : Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (London: Verso, 2019). ↵

- John Willis, Mni Wiconi: Water is Life; Honoring the Water Protectors at Standing Rock and Everywhere in the Ongoing Struggle for Indigenous Sovereignty (Stauton: George F. Thompson Publishing, 2019). ↵

- John Willis, Indigenous women leading frontline action to location where the Dakota Access Pipeline is being buried in the ground. When the police asked them to turn around and leave with their approximately 200 supporters, they agreed to do so only if the police would join them in a prayer for the water. Once the police agreed, prayed with the group, and drank some sacred water, the Water Protectors peacefully returned to camp, 2016, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020.360, accessed May 24, 2022, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/675863/indigenous-women-leading-frontline-action-to-location-where. ↵

- Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, email statement to the curators, December 15, 2020. ↵

About the Author(s): Marina Tyquiengco (CHamoru) is the Ellyn McColgan Assistant Curator of Native American Art; Layla Bermeo is the Kristin and Roger Servison Curator of Paintings; and Tess Lukey (Aquinnah Wampanoag) is the former Henry R. Luce Curatorial Research Fellow, all at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.