Commercial Design and Midcentury Asian American Art: The Greeting Cards of Tyrus Wong

The term “Asian American art” was propagated in the late 1960s by activists engaged with the contemporary racial justice movement and may therefore imply a politicized and oppositional aesthetics. The label can be misleading for ethnic Asian artists practicing before the late 1960s, whose biography and aesthetic concerns differ.1 For example, celebrated watercolor painter Dong Kingman (1911–2000) is known for an expressive watercolor style in which “lively impressions of America” are “handle[d by] brush in an adept Oriental fashion.”2 Dong’s syncretic style reflects his biography as a native-born US citizen who started formal art education in China, studying with a teacher trained in both European and Chinese painting techniques. Far from the confrontational positioning of the generation that succeeded him, Dong found ready support within the US cultural establishment. In the 1930s, Dong was one of many young artists supported through the Depression by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and, in the mid-1950s, he traveled throughout Asia on behalf of the US State Department as part of a goodwill tour promoting transpacific relations.

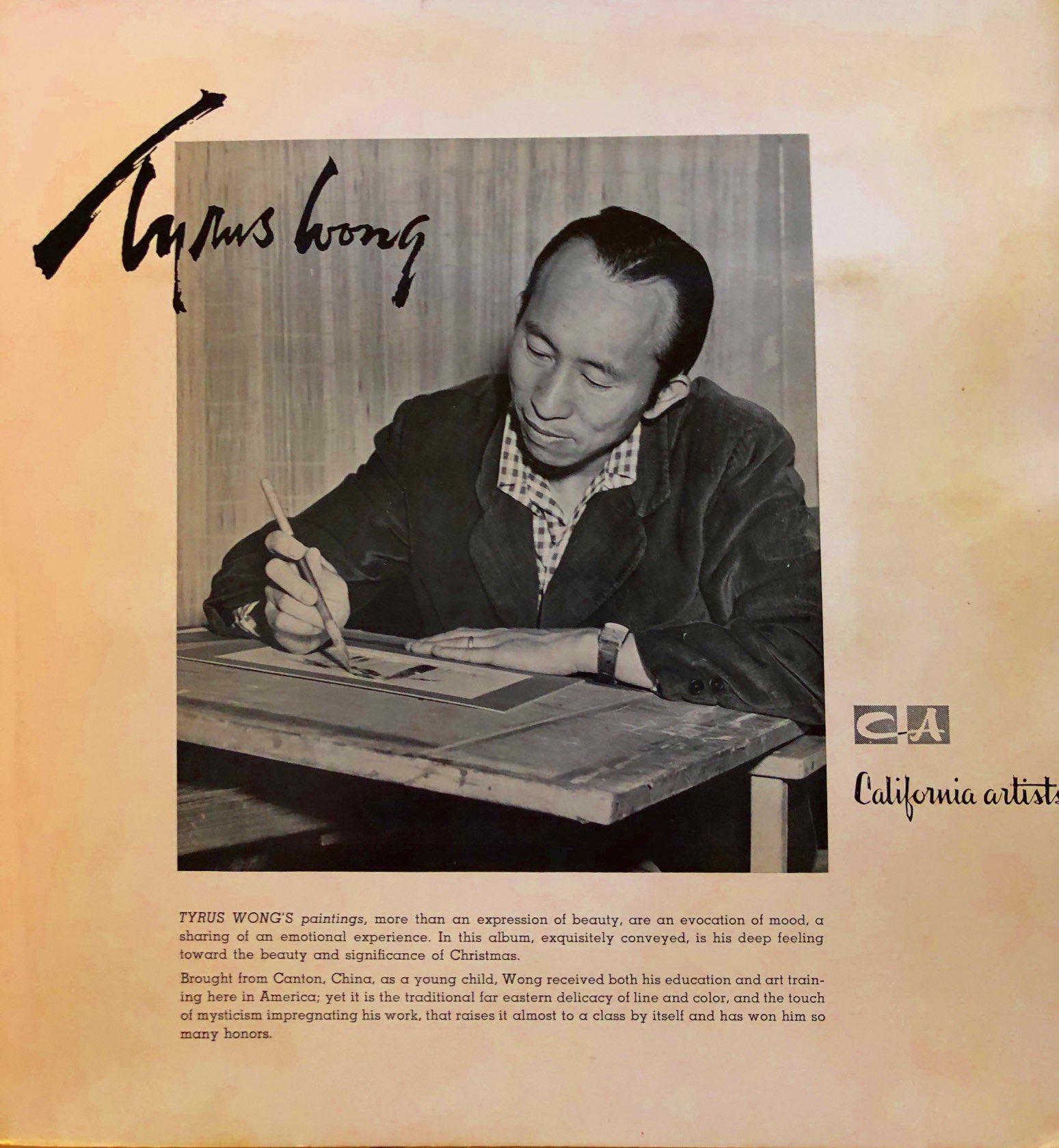

Another example is the Hollywood production illustrator and greeting card artist Tyrus Wong (1910–2016). Best known for his instrumental role in the 1942 Disney film, Bambi, Wong was an eclectic artist whose work spanned the domains of commercial and fine art, and who was influenced by both eastern and western art traditions.3 Prior to his work at Disney, Wong was an artist with the Federal Art Project, and during nearly three decades at Warner Bros. as a studio sketch artist, he also moonlighted doing decoration and illustration commissions in a variety of media. Most notably, from the early 1950s through the mid-1970s, Wong was one of the nation’s leading greeting card artists. His holiday cards were published by Hallmark—then (as now) the nation’s leading greeting card publisher—and in many years his designs were bestsellers.4 In 1954, Wong’s atmospheric image of a miniscule shepherd posed under hot pink tree boughs and gazing up at a star in the sky, which the artist painted for the Los Angeles–based greeting card publisher California Artists, sold more than one million copies (fig. 1).

This essay explores Wong’s holiday cards as one example of precursors to Asian American art in the period prior to the 1970s. Although greeting cards were just one chapter in Wong’s unusually long and diverse artistic practice, little attention has yet been paid to how this ubiquitous art form relates to the artist’s other personal and professional interests.5 This oversight is partly due to the still developing understanding of commercial and nonwhite artists such as Wong, as well as a general dearth of critical study into greeting cards more generally.6 Yet, despite the many fascinating episodes in Wong’s life and career, in his later years the Disney legend still cited greeting cards as the work of which he was most proud.7 The household prominence that Wong gained through greeting cards, as well as their format and style, present an important case study of Asian American art at midcentury. In addition to documenting the vast but little-understood greeting card industry, Wong’s cards and their extraordinary reach illustrate the opportunities that minority and marginalized artists might have found in commercial art.

Wong’s “Blend of Oriental and Occidental Cultures”

“I think, all of us, when we were young, saw [Wong’s] Christmas card designs,” notes art historian Mark Johnson, whose role in the pioneering 1995 exhibition at the Fine Arts Gallery of San Francisco State University, With New Eyes, helped direct attention to Asian American art history.8 In a vivid personal anecdote that illustrates the popularity of Wong’s cards, historian Suellen Cheng shares how, newly arrived from Taiwan to begin graduate study at UCLA in the mid-1970s, her white roommate’s mother extolled “Tyrus Wong, the Chinese artist” behind her “favorite Christmas cards.”9 The woman’s impromptu outburst shows how extensively Wong’s holiday cards penetrated US households and how effective they were in publicizing his name.

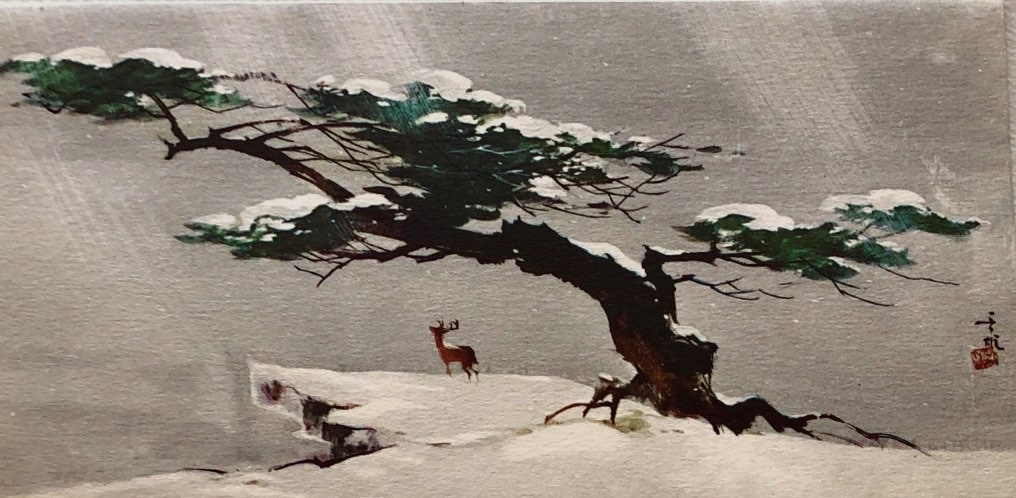

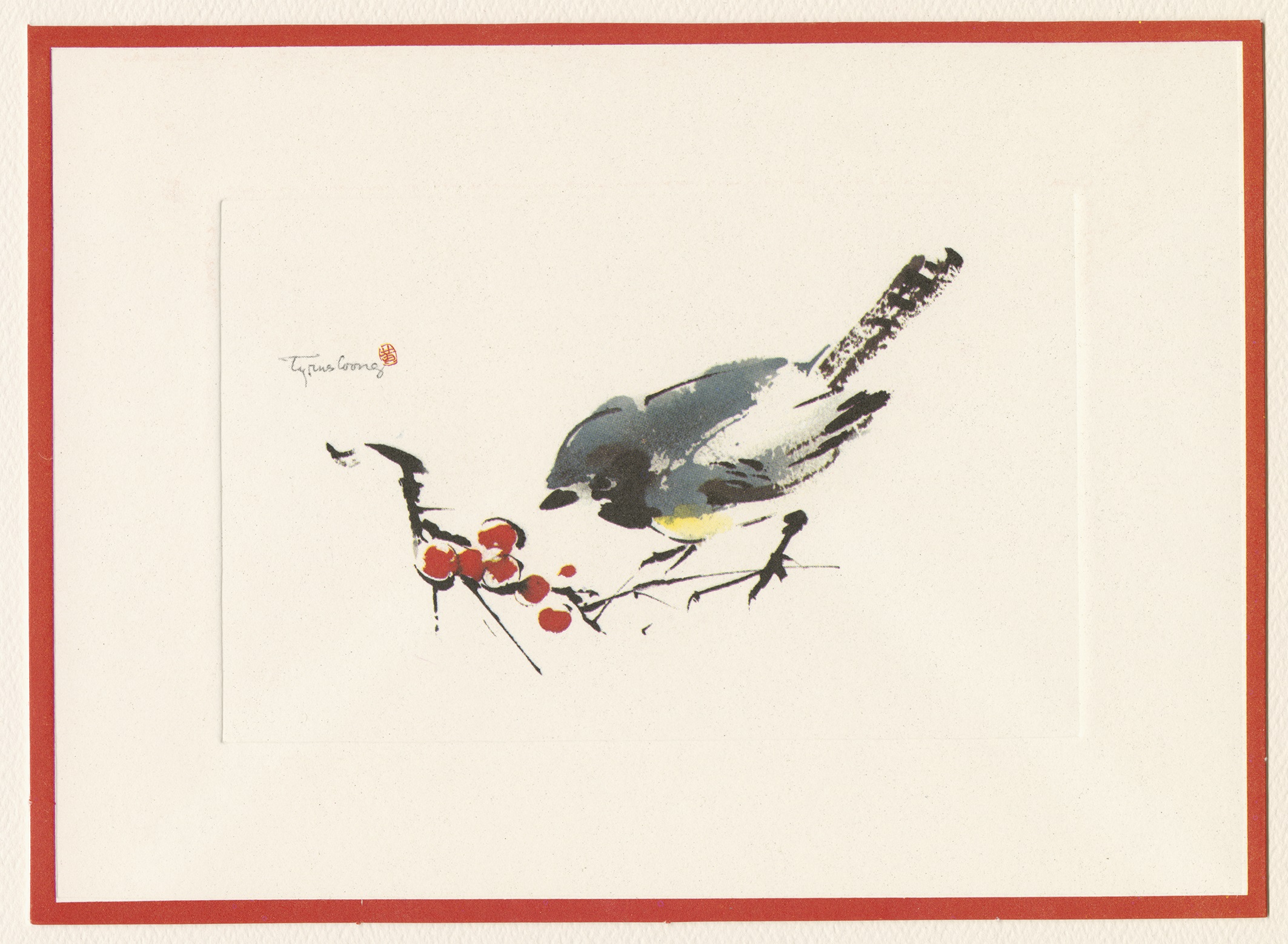

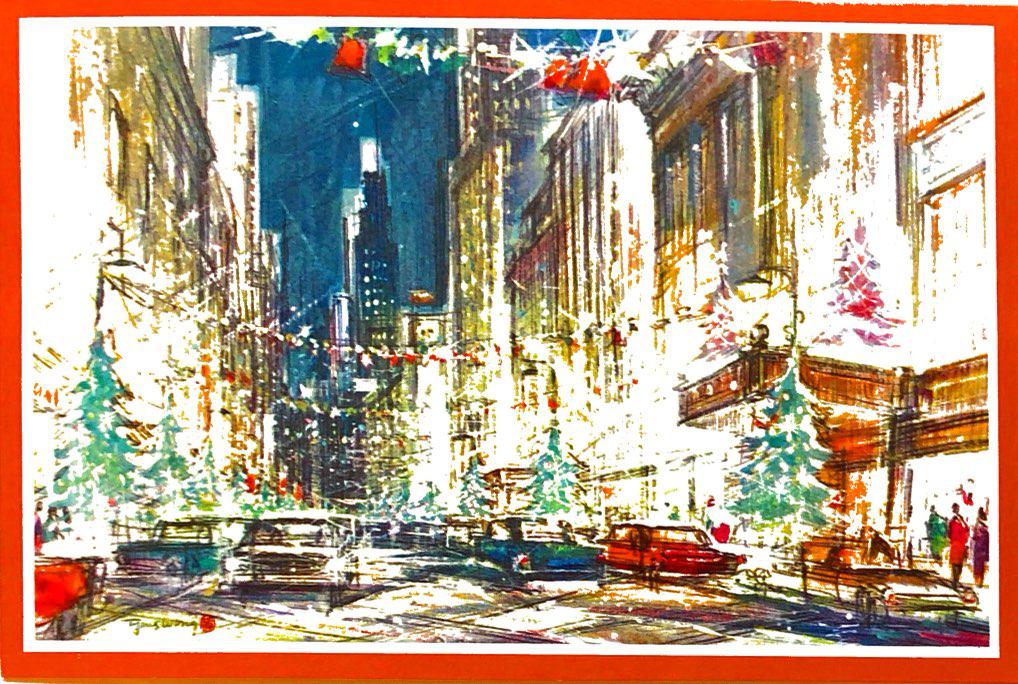

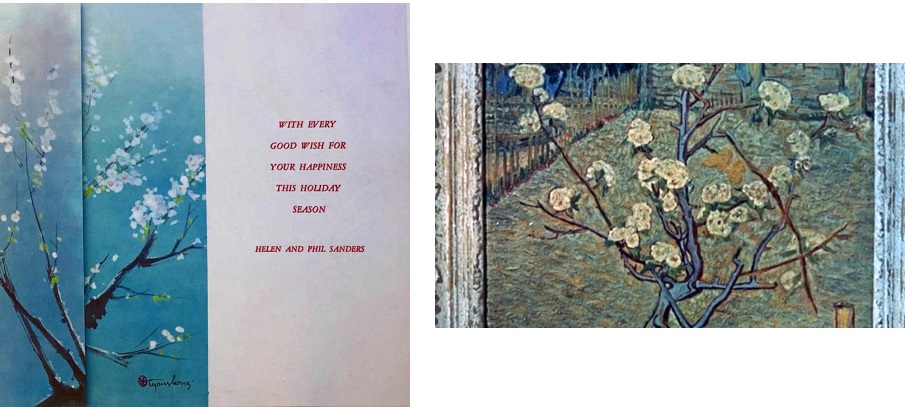

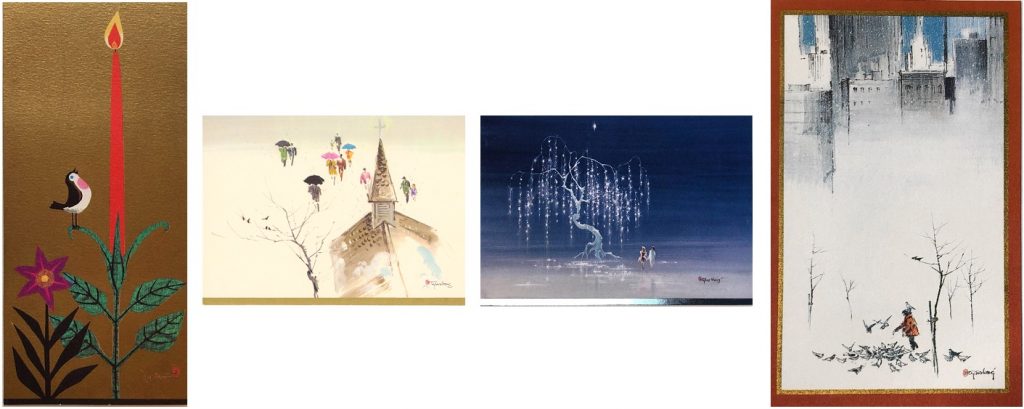

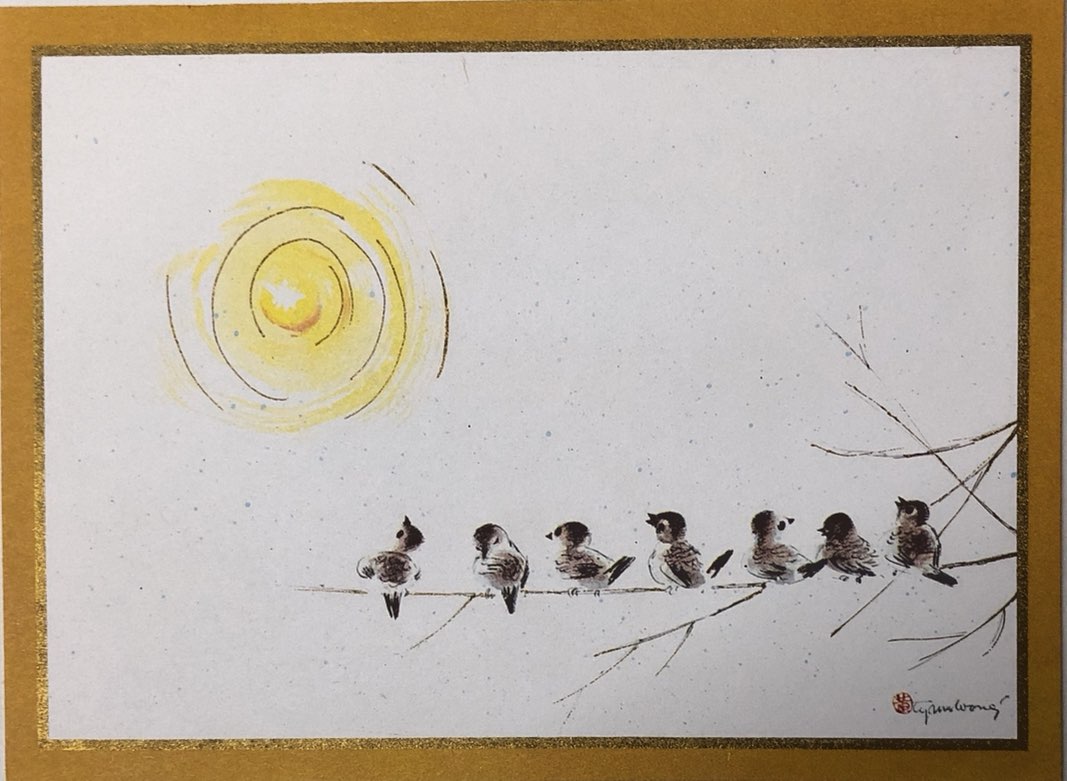

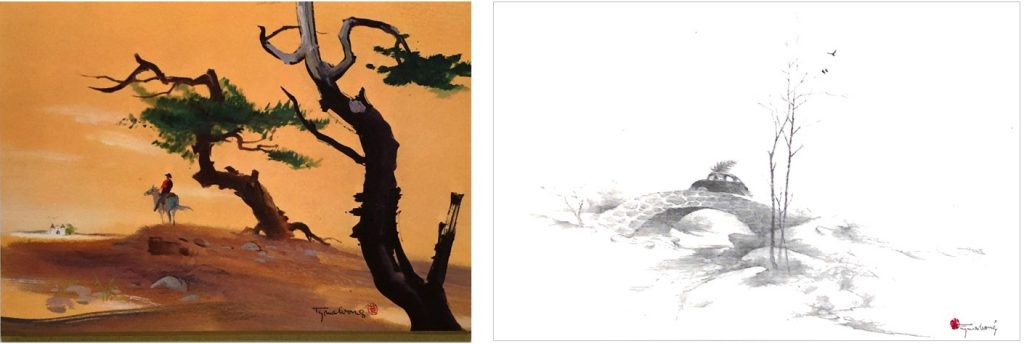

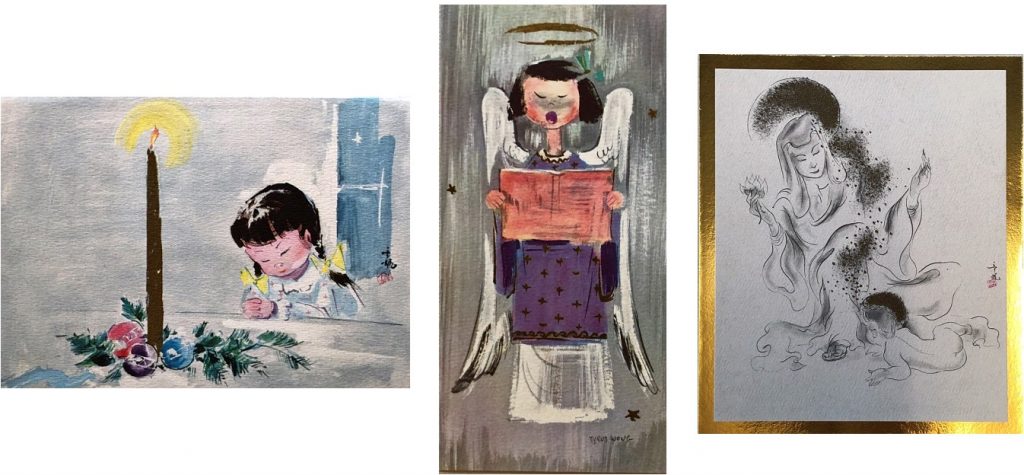

The popularity of Wong’s holiday cards may be surprising, given the stylistic and thematic incongruity of a Chinese designer of Christmas cards. Most of his card designs—including all of Wong’s bestsellers—resemble traditional Chinese painting through their gestural brushwork devoid of linear perspective (fig. 2). Whether applied to traditional Christmas imagery—such as wreaths, angels, elves, wrapped gifts, the Nativity and Three Wise Men, or secular seasonal imagery such as snowscapes, deer, birds, or holiday décor—his striking application of eastern aesthetics to a western, Christian holiday might be described as proto-“Asian fusion.”10 Asian attributes are sometimes overt, such as “bird-and-branch” paintings that evoke Chinese scrolls (fig. 2d).11 Just as often, the orientalism is more subtle, such as monochrome images that recall sumi-e ink painting (fig. 2e) or a mysterious landscape with sharply angled distant rooftops that suggest a pagoda but, upon closer inspection, are a church steeple (fig. 2f).

Fig. 2. Greeting cards by Tyrus Wong

This syncretic, culturally multivalent style was featured and embodied by Wong himself. Like many successful greeting card artists who did not simply create images for imprints but whose signature style was key to sales, Wong almost always signed his greeting cards.12 His doubled mark included elements in both English and Chinese. Sometimes he signed his name in English script, accompanied by a traditional red seal or chop mark with the Wong surname in Chinese. Other times he wrote his Chinese name, Tai Yow, in Chinese calligraphy, accompanied by an orientalist seal in which his English name is painted in red and enclosed within a chop mark in a round or square shape.13 As in traditional Chinese and Japanese painting, these artist marks are an important compositional element, instrumental in establishing the oriental sensibility. Yet, because the double signature simultaneously invokes Wong’s Chinese ethnicity and westernized identity and audience, the marks also literalize his Asian American identity.

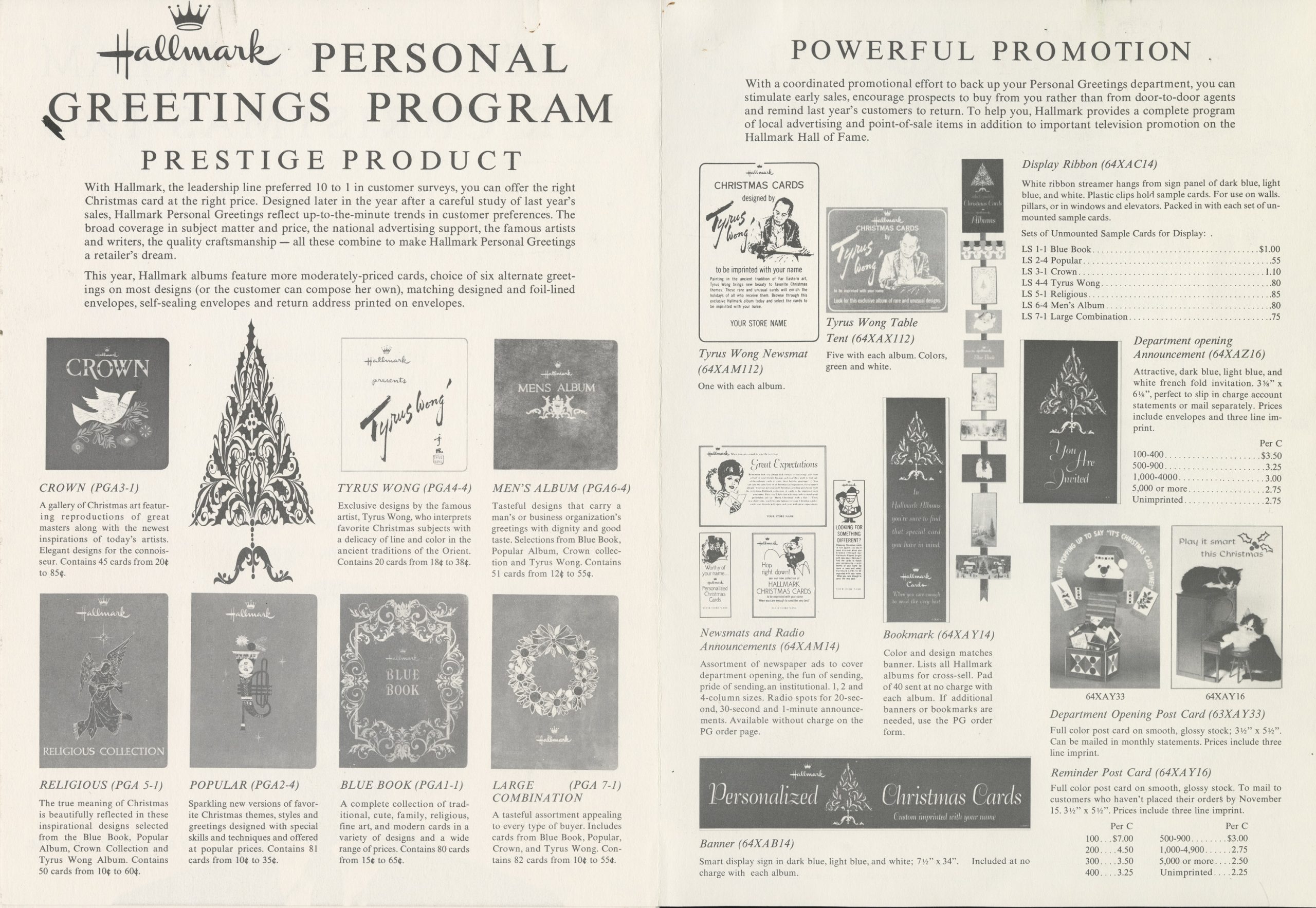

The greeting card companies were consistent in making Wong and his bicultural identity key to the branding of his cards. Contracts specify that the publisher is “obligated to use [his] name” on designs and marketing, and by 1974, Wong’s Looart contract noted that if his designs were reissued, cropping or modification would “not disturb or remove the signature of the Artist.”14 Hallmark even considered asking him to make public appearances in Los Angeles.15 Although Wong declined to cooperate, Hallmark’s formidable publicity and marketing team developed substantial promotional materials, creating table tents, foldout posters, and other exhibition ballyhoo. In 1964, Wong was the only individual artist the company granted such a promotional campaign (fig. 3).

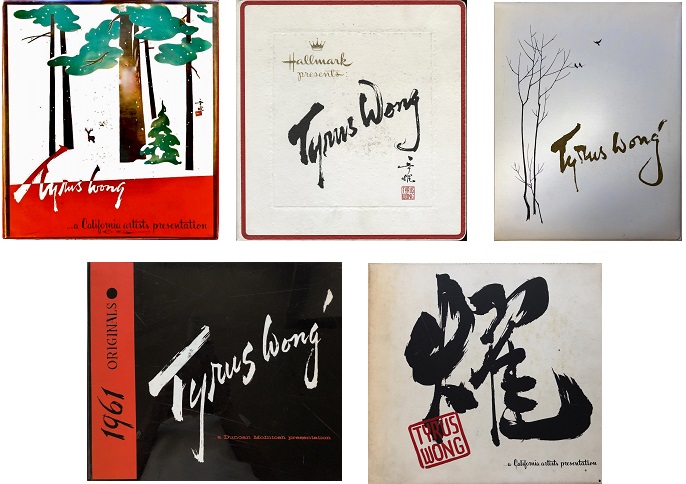

To further link Wong’s designs with his identity, greeting card publishers showcased his work in exclusive series that highlighted his biography and unusual style. In the annual display albums created by greeting card publishers for retailers and customers, Wong’s designs merited their own volume, with his signature as the cover decoration (fig. 4; individual cards were also included in assorted collections). Inside the albums, designs were prefaced by a short biography page with a photograph of Wong and a description of his Chinese birthplace and US art school training (fig. 5). In a typical account, one biography highlights how Wong’s “blend of Oriental and Occidental cultures” conveys the “tradition of the great Chinese painters translated into Western seeing.”16

“All Things to All People”

Wong’s distinct blend of cultural stylistics was not unprecedented, nor were greeting cards the first medium in which his work coincided with a general taste for Asian aesthetics. Wong’s father taught him traditional Chinese calligraphy when he was still a child, and he supplemented his formal education in western art history at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles by browsing books about classical Chinese painting. Wong particularly admired the Song dynasty (960–1279 ad), an era known for idealized, atmospheric landscapes in which diminutive figures convey the vastness of nature. By graduation, Wong was already known for an evocative blend of artistic traditions, such as copperplate etchings of Chinatown vignettes or nudes with a suggestive calligraphic line. In the 1930s, Wong painted a full-length portrait of Jesus with slanted eyes, floating in clouds. His prolific capacity for orientalized ephemera was also foreshadowed in dozens of menu covers he painted for the Dragon’s Den, a bohemian Los Angeles Chinatown restaurant. In the menus, Wong’s Chinese-style still lifes and calligraphy are accompanied by his distinct double artist mark.

From Wong’s arrival in the United States as a young child in 1920, his life and career were impacted by the practices of the Chinese Exclusion Act, still in effect for the first quarter-century of Wong’s life in the US. It first confronted him at the immigration center at Angel Island, when he was separated from his parent and spent a month detained there. As a student, an ill-planned sketching trip to Tijuana in 1931 temporarily prevented him from reentry to the United States, and his WPA appointment ended abruptly when administrators discovered his lack of citizenship—a condition that by law he could not help. Such race-based complications are evident in the ambiguous critical discourse on his nationality. In an international exhibition of etching and engraving held at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1932, Wong is listed only by his first name—as if to obscure his race—while a later exhibition lists him as part of the “China” contingent.17 He was a founding member of the California-based Oriental Artists Group, which exhibited both US-born and immigrant artists, and although his work was included in the “American group” sent by the US government to represent the Federal Art Project at the 1937 Paris Exhibition, coverage describes Wong as a “brilliant young local Chinese.”18 The Los Angeles Times, despite being a frequent and vocal supporter of Wong, similarly was vague about Wong’s nationality, praising his work for “some of the most beautiful figure drawings ever done,” while elliptically describing him as a “Los Angeles–based Chinese artist.”19

For various reasons, Wong shifted to commercial work by World War II, and the postwar period brought changes that dramatically affected his artistic production and reception. Most important, Wong became a citizen in 1946, only a few years after the United States ended Exclusion; the end of the Alien Land Laws also enabled his family to purchase a house. Both were facilitated by steady employment at film studios. Moreover, as one of the first professional Chinese families to move to the Los Angeles suburbs, Wong and his family became exemplars of the new Asian American middle class. In 1957, the Wong family was the subject of a five-column, above-the-fold article in the Christian Science Monitor describing how the family “preserves festive oriental customs” while being “welcomed in [the] U.S. community.”20 In the accompanying photograph, the family is posed near their house, with Wong and his daughters in Western dress and his attractive wife Ruth in the tight fitting, cheongsam dress then fashionable through Hollywood movies—a picture-perfect Chinese American family embodying assimilation and the national benefits of multiculturalism.

More specific to Wong’s artistic career, midcentury’s new entente between the United States and Asia rejuvenated a long-running interest in Asian culture and aesthetics. This trend was partly due to wartime familiarity with the Asia-Pacific region, and even with China’s turn to communism the US government continued to foster public support for its interests in the region by funding Asian arts and culture. As Christina Klein has shown, the trend is also evident in high-profile Hollywood musicals and films such as South Pacific, Flower Drum Song, The Sand Pebbles, The World of Suzie Wong, and Love is a Many-Splendored Thing.21

Despite launching his career amid the Post-Impressionist taste for Japonisme, Wong benefited most from the midcentury’s enthusiasm for Asian art and aesthetics. In 1944, he illustrated a short story about the Japanese invasion of China for the monthly magazine Western Family.22 In 1949, Wong did pen-and-ink illustrations for Footprints of the Dragon, a novel about how Chinese labor built the Transcontinental Railroad, part of a series to promote US interests in Asia.23 Throughout the 1940s, Wong decorated special-order, high-end ceramic dinnerware available for sale in better department stores.24 His film studio assignments also sometimes drew directly on his Asian identity and style. For the 1952 Korean War film Retreat, Hell!, Wong did Chinese lettering for the set, and in the lavish 1961 Delmer Daves melodrama Susan Slade, featuring a chic midcentury modern house with sliding glass doors resembling Japanese shoji panels, Wong created a painting of twisted cypresses shown in close up.

Given the contemporary interest in Asian aesthetics, it is not surprising that Wong’s fusion-style greeting cards attained such success. When friend and fellow Disney and Otis colleague Dick Kelsey, then art director at local greeting card publisher California Artists, suggested that Wong try designing Christmas cards, Wong initially demurred, but soon submitted three images: a young girl playing with a tinsel ball, a bird inside a mailbox, and a landscape with deer. He was pleasantly surprised as all three “zoomed up” the sales charts, “really selling like hotcakes!”25 In 1952, Wong’s success helped California Artists sales achieve over five times that of the previous year.26

Moonlighting in greeting cards was a common sideline for commercial artists. Postwar prosperity, cheaper printing technologies, and a rapidly growing and increasingly mobile population propelled the industry to new heights, providing ample opportunity for artists to supplement their income. Among Wong and Kelsey’s Disney contemporaries alone, animators Joe Grant, Stan Spohn, Eyvind Earle, John Hench, Tee Hee, and Mary Blair earned extra income by creating card designs.27 In 1955, just a few years after starting, Wong was named California Artists’ “Artist of the Year,” offering a series of twenty-five designs. By 1958, the company claimed “perhaps the reason Tyrus Wong has so rapidly become a favorite Christmas artist is that his paintings are all things to all people.”28 “Surpass[ing] his own work year after year,” as a 1961 album from publisher Duncan McIntosh described, by 1967 Wong was dubbed “America’s favorite Christmas card designer.”29

Process and Sales

To fulfill this high-profile sideline, Wong blocked time around his regular employment at Warner Bros. Greeting card manufacturing timelines usually required that holiday season designs be submitted by early fall of the preceding year, meaning Wong was dreaming up winter scenes in the mild southern California summer.30 To get in the mood, Wong listened to Harry Belafonte Christmas albums. His American-born wife, Ruth Kim Wong, was a key collaborator, as Wong himself did not celebrate Christmas until his marriage. Ruth, a former Sunday school teacher whose parents were Christian converts and who herself had studied literature at UCLA, suggested titles and imagery and provided text for printed messages and marketing (often drawing on scripture and literature). Card work was omnipresent in the family’s home life; although Wong created his designs in a studio steps away from their house, he kept a small sketchbook by the bed to jot down ideas (fig. 6), and Ruth typed business memoranda at the kitchen table. Once Wong completed the requisite two dozen sample designs, the original art would be shipped to the publisher for selection and styling.31 In Wong’s case, designs were mostly executed in gouache and opaque watercolor on board. Greeting card imprints would photograph these, assemble the complete design, and print the cards.

Wong’s cards by regional brands, such as Duncan McIntosh and California Artists, were sold to Los Angeles– and California-based consumers in the stationery sections of local department stores such as Bullock’s, The Broadway, Coulter’s, and Robinson’s, or gift shops and pharmacies such as Paul J. Howard Floral and the Owl Drug chain. Warner Bros. colleagues were reminded in the company newsletter that they could find them in the studio gift shop.32 For national distribution, Duncan McIntosh sold designs to New York–based stationery brand, E. Errett Smith, which resold designs to Sears, Roebuck; Hallmark, of course, had national distribution.33 At twenty-five to thirty-five cents per card, Wong’s designs were on the higher end of contemporary prices. His cards often came with foil details, rice paper sleeves, and other embellishments that justified their higher cost. Many series also included one or more trifold cards, whose large size positioned them as luxury purchases (see fig. 10, left). The cards were sold as loose, individual cards or in boxed sets. One purpose of the display albums was to promote customized orders; premium buyers could choose envelope designs and have their address and personalized message preprinted on envelopes and the card interior.34

To keep his brand consistent, Wong reproduced favorite motifs from year to year. He usually balanced between the religious and secular, with vignettes and tableaux recurring annually, such as the aforementioned birds-on-branches or deer in the woods, nativities, shepherd scenes with the North Star, and Joseph and Mary’s journey to Bethlehem (fig. 7, top left).35 Other designs did not recur quite so frequently but were striking enough to constitute an ongoing theme. Each annual series, for example, usually included one elf or pixie, often fancifully drawn and dwarfed by outsized holiday ornaments or seasonal paraphernalia (fig. 7, top right). Other favorite themes included a solitary boat (fig. 7, bottom left) that appeared once a year from 1961 to 1975; bringing home the Christmas tree, done frequently from 1956 to 1975; seasonal scenes set inside or outside a church or on city streets; rainy scenes of crowds carrying umbrellas; and views in the country or western landscapes. Oversized yucca nod to Wong’s California location while effecting a Christmas tree-like motif through their elongated triangular shape (fig. 7, bottom right). The brilliant pink boughs of the 1954 million-selling “Shepherd” card inspired a series of hot pink trees, appearing in two different images in 1955 and 1959, as well as new individual versions in 1956, 1957, and 1958.

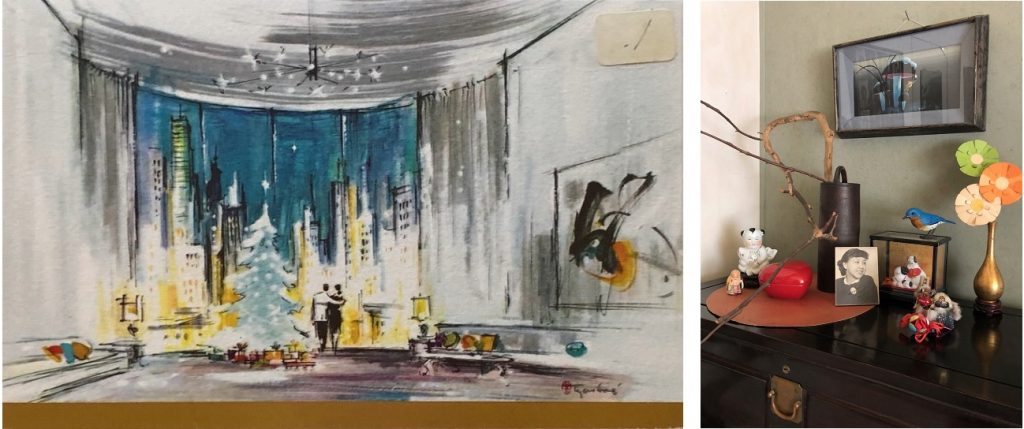

As his career continued, card designs also reflected Wong’s cinematic work. His Disney experience is particularly obvious in kitschy subject matter such as rosy-cheeked cherubs and small animals at play (fig. 8), and his facility with deer, Wong joked, was “maybe a hangover from Disney?”36 But the transmedia influences of Wong’s film studio work extend beyond such obvious content to more general cinematic references. Western and country settings reflect the film genre’s popularity (Wong also enjoyed Westerns), and urbane scenes of busy streets and stylish interiors resemble his studio sketches. The grand, sweeping staircase in “Holiday Elegance” and the urban streets decked with holiday decor of “Festive City” (fig. 9; both Duncan McIntosh cards from 1963) recall scenes from the 1958 Warner Bros. comedy Auntie Mame, a film on which Wong worked.37 Similarly, his 1967 “Blissful Bird” card of white tree blossoms against a cerulean sky is unmistakably Van Gogh–like, probably inspired by Wong’s work the previous year on Any Wednesday, which includes a close-up of a similar faux Van Gogh, a prop Wong may have painted (fig 10).

Cinematic influences are also felt in the card composition. For example, not all of Wong’s card designs are in his signature brushy style. Some have the graphic, cut-out shapes of Pop Art, possibly influenced by contemporary animation (fig. 11, far left). The high-angle aerial perspective in “Steeple in the Rain” (fig. 11, second from left) and “Over the Hills” (1968; Duncan McIntosh) recalls a crane shot, conventionally used in film to introduce a location or as a concluding image. Other romance- and fashion-centered cards have the artificial setting and absence of depth seen in contemporary musicals (fig. 11, third from left), and the elon-gated “Cityscape” (1974) resembles a movie poster with its foreshortened layering of a child feeding pigeons in the foreground against a loosely sketched urban skyline (fig. 11, far right).

Given the imperative to provide constant new content consistent with his brand, Wong and his publishers were not averse to recycling his most successful designs (fig. 12) or combining favorite motifs for new, compound designs. His bestselling card for Hallmark, an elegant red-bordered image of a bird pecking berries (see fig. 2, bottom left), was reissued in the two following years after selling nearly one hundred forty thousand copies in 1964.38 When “The Offering,” a sentimental image of the Christ child slumbering in a manger, became Duncan McIntosh’s top-selling card for 1962, it was reissued twice—once immediately afterward and then by Metropolitan in 1973, reformatted with a generous double border trimmed with foil and a printed motto.39 Among his mixed motifs, a mounted cowboy rests beneath Wong’s signature brushy pines while gazing at a remote church steeple (fig. 13, left), and an explicitly contemporary vignette of an automobile bearing a cut Christmas tree is given a timeless and placeless sensibility through a soft, monochrome landscape reminiscent of Chinese ink painting (fig. 13, right).

In terms of earnings, the financial dividends were considerable. Wong’s exclusive designs—bound by an annual noncompete clause prohibiting him from designing cards for other imprints—were compensated by 10 percent royalties on sales.40 Royalties were sometimes partially paid in advance, and greeting card companies issued regular reports tabulating sales for individual designs.41 “Something I can remember us doing as a family,” recalls Wong’s oldest daughter, Kay Fong, was to look at “how his Christmas cards were doing, . . . where the cards were ranked, . . . and which cards were doing better than others.”42 Such precise sales data was a tangible indicator of professional success, very different from the relatively anonymous work of a studio preproduction illustrator. Contracts continued past his late 1960s retirement from film studios: in the mid-1970s, Colorado-based greeting card publisher Looart promised Wong $14,500 annually.43

The material and immaterial benefits of Wong’s greeting cards also extended beyond royalties to include complimentary boxes of designs, private sales of original art, and personal connections with buyers and collectors, which sustained his renown and occasionally resulted in additional sales. While greeting card publishers retained original art for display and promotional purposes and reserved first right of purchasing refusal, once the season concluded, unpurchased samples reverted to the artist.44 Wong used his original art and guaranteed free boxes of cards as fungible capital. He and Ruth gifted complimentary boxes to family and friends, saving on household expenses and currying favor with the recipients.45 As the inventory of returned paintings mounted, Wong sold originals through private transactions or donated them, augmenting his public visibility and capitalizing on this additional source of income.46

The marketing alignment of his cards with Wong himself remained important in these intimate, private interactions. In the mid-1950s, after meeting a couple at a local art fair, Wong invited them to his home studio, where he sold them several greeting card originals.47 As evidence of his national reach, in 1964, a New Jersey woman wrote to Wong asking about his inspiration for a previous Duncan McIntosh card. His reply (probably composed by Ruth) thanks the writer and subtly reminds her of current products by asking her opinion of “my album of cards designed for . . . this year.”48

Wong’s ability to enrich the appeal of his cards by his very presence was increasingly important as imitations proliferated. Today, many of the vintage cards available on eBay as an “authentic Tyrus Wong Christmas card” are not his but are instead contemporary imitations of his style. His family recalls often finding orientalist holiday cards that resembled his, and the Hallmark Archives have several unpublished items made to copy Wong’s style. Imitation, as they say, is a form of flattery.

Greeting Cards, Commercial Art, and Minority and Marginalized Artists

“But a Hallmark card?!?,” spluttered one of my colleagues in disbelief when hearing about this part of Wong’s career. This reaction is typical of the ambiguous status that greeting cards hold in critical study. As mass-produced ephemera bearing canned sentiment and imagery, greeting cards are often disregarded as cultural artifacts with little aesthetic or intellectual value. The Hallmark card, as my colleague’s comment reminds us, may be a universally familiar cultural object, but its ubiquity is also why traditional art history often overlooks the genre, and few serious writers want to be associated with it.49

Yet at its height in the middle of the twentieth century, the greeting card industry sought high-profile, high-art collaborations—Saul Steinberg, Andrew Wyeth, Andy Warhol, Robert Indiana, and Salvador Dalí are just some of the internationally acclaimed artists who produced Christmas card designs when Wong worked in the genre.50 For some, greeting cards were not seen as crassly debased moneymaking opportunities but as unrivaled platforms to bring their art to a general public. After all, greeting cards are one of the most immediate, extensive, and intimate venues by which people experience fine art and design. The accessibility and affective value of cards encouraged beloved poet and cultural icon Maya Angelou to start a lucrative Hallmark collaboration in 2002, staunchly ignoring high cultural disdain in favor of mass cultural connection.51

While it is not clear how much Wong himself knew about the industrial history of greeting cards, it is worth noting how that history underscores larger issues of nationality and cultural belonging that resonate with Wong’s career. Despite their origins in nineteenth-century German printing innovations and British bourgeois customs, by the middle of the twentieth century, greeting cards were a distinctly American phenomenon. Americans exchange more greeting cards than any other nation in the world, and Wong’s collaboration with Hallmark took place when the company was one of the most influential in the United States, notable for growing a previously nonexistent consumer sector into a media, retail, and real estate powerhouse. Within this context, it is intriguing that national brands, such as Hallmark, and smaller regional operations, such as California Artists, sought Wong’s exoticized imagery.52 That greeting card companies staked their vitality on a nonwhite immigrant and former “alien excluded from citizenship” is a striking indicator of changing US relationships to ethnic Asians at midcentury.

Wong’s career presents several implications for Asian American art history. First, the unusual visibility he enjoyed at midcentury reflects the postwar climate, when the end of Exclusion changed former stereotypes of Chinese as perpetual foreigners toward assimilation and multiculturalism. Shaped more by contemporary immigration and foreign policy than by cultural activism and birthright assertions of US identity, Wong shares transnational and assimilationist attributes notable among other contemporaries, like Dong Kingman, whose careers precede the Asian American label.

Second, the particular conditions of pre-1960s Asian American artists invites us to rethink longstanding suspicions of orientalism. Since Edward Said and the anti-orientalist work of Asian American artists and cultural critics such as Martin Wong and Frank Chin, scholars are justly suspicious of exoticizing and essentializing modes of representation. We should, however, also consider the obstacles and possibilities shaping earlier figures. Wong, for example, was friendly with Hollywood screen siren Anna May Wong and witnessed how little such a hugely visible figure was able to combat contemporary stereotypes. If Asian American art and art history are legacies of post-1960s postcolonial critique, we must also acknowledge different artists and practices that precede that era, when some ethnic Asian artists in the United States employed strategic and intentional exoticization as a means of advancing personal, professional, and aesthetic capital.

Third, beyond the obvious material rewards of greeting cards, it is also worth considering the intangible personal meanings this phase of his career might have exerted for Wong. Like many artists, Wong embellished personal correspondence with doodles and decorations. One of his great joys was an ongoing joke correspondence of cartoons and other silly imagery with longtime friend Gilbert Leong, a noted Los Angeles architect, and his daughters joke about how quickly Wong struck from the list anyone who failed to reciprocate an annual holiday card. Not surprisingly, as a pragmatic and unpretentious person without embarrassment about working across fine and commercial art, Wong had a playful relationship with the greeting card genre. One 1962 design for Duncan McIntosh includes a well-appointed interior with a large abstract expressionist painting reminiscent of Wong’s fine art (fig. 14, left). And the original painting of “Christmas Elf,” a Disneyesque vignette of an elf capturing a dewdrop from a mushroom from early in Wong’s greeting card career, hung for decades in his bedroom, suggesting untold personal and career memories (fig. 14, right).

Wong’s retrospective description of the genre as the phase of his career of which he is most proud raises questions about how greeting cards facilitated his artistic ambitions. In later years, Wong occasionally invested cards with cultural and aesthetic gravitas, situating them within his career by invoking the august tradition of Chinese painting. “Because I study Chinese landscape,” he reflected in 2015, just a year before his death, his images often have a “tiny little figure,” to show “man against nature; man is nothing compared to nature.”53 Ruth made similar points while writing marketing materials. Perhaps reviving her language was a way of honoring her memory and engaging the growing number of scholars inquiring about his life and career. It also offers his perspective on the syncretic and transmedial practices of his early fine art career and through the different media and venues in which worked.

Yet such inflated rhetoric, while consistent with intentional orientalism, seems belated, particularly in contrast to the evident symbolism with which the cards materialized his family’s cultural embrace. By synthesizing Chinese-style brush painting with Christian or American scenes, Wong’s cards show how domestication and naturalization drive the transnational and bicultural quality of Asian American art in this era. This is apparent in cards such as his 1956 “Christmas Prayer” card, showing his youngest daughter Kim as a child at devotion (fig. 15, left), or another of a caroling brunette angel that could be middle daughter Tai-ling (fig. 15, center), or a simple monochrome cartoon of an orientalized Madonna and Child, whose wimple recalls Ruth in a forties victory roll hairstyle (fig. 15, right). These card designs are less suggestive of Wong’s Chinese heritage than symbolic of assimilation and biculturality.

Finally, Wong’s remarkable history as “America’s Favorite Card Designer” should be a reminder of the particular opportunities that commercial art held for minority and other marginalized artists, and a clarion call for greeting card scholarship. Both lacunae reflect art history’s focus on a unique, attributable work and overlook how commercial venues offered opportunities to artists whose personal and professional aspirations were complicated by race, gender, class, or—as for Wong—legal prohibitions. As curator Sonia Mak recalls, Los Angeles artist Bill Jong was frank about how “at a time when it was difficult to be in any type of creative field—during the Exclusion Act—it wasn’t such a bad deal to make a living doing a type of creative work and have people appreciate what you do.”54 Moreover, Wong’s exclusive designs place his authorship in the foreground. Unlike film studio work, the holiday cards were created according “to my own brain, my own thinking,” publicizing his name as it went straight from him to the individual buyer and recipient.55

One intriguing aspect of Wong’s prolific holiday card designs is that—despite numerous elves and evident willingness to orientalize Western holiday imagery—over twenty years designing Christmas cards, he painted very few Santas.56 Santa’s absence is an intriguing hint of how Wong’s cards enacted and embodied public renown and unprecedented acceptance. At the height of his greeting card career, Wong’s name was recognized by countless US consumers. By rarely complicating his holiday images with a persona as distinct as Santa, Wong ensured that his name and unique art was remembered and cherished. They may have been “just Hallmark cards,” but they also were calling cards—valentines to a country with which Wong had a complicated history and triumphant assertions of his artistic-professional success.

Cite this article: Karen Fang, “Commercial Design and Midcentury Asian American Art: The Greeting Cards of Tyrus Wong,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11548.

PDF: Fang, The Greeting Cards of Tyrus Wong

Notes

Author’s note: This research draws primarily on the twenty-one display albums of Tyrus Wong greeting cards showing his exclusive series from 1955 through 1976 (with the exception of 1960, which is missing), as well as business correspondence and personal notes in the Wong family papers. The Hallmark Archives also generously shared records of Wong collaborations. The author is grateful to the Wong family for access to their vast archive and to Hallmark archivist Samantha Bradbeer for her knowledge of the company archive and history. Earlier versions of this research were presented at the 2020 Rockwell Conference for Illustration Studies, Hunter College and the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, and the Visual Studies Institute of the University of Southern California. The author thanks Jennifer Greenhill, Michael Lobel, Stephanie Plunkett, and Vanessa Schwartz for their interest; Beatrice Chan, Suellen Cheng, Sonia Mak, Ted Scheinman, and Pamela Tom for their insights and questions; and Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, Marci Kwon, Christopher Lukasik, Jessica Skwire Routhier, and Naomi Slipp for comments on this manuscript.

- Gordon H. Chang, Mark Dean Johnson, and Paul J. Karlstrom, Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008). ↵

- “Dong Kingman’s U.S.A.,” Life, May 14, 1951, 100–2. Although the artist followed Chinese tradition in putting his family name, Dong, first, references to him and his work often mistakenly use Kingman as his surname. This historical artifact is itself typical of Asian American experience, but given this issue’s focus on Asian American artists, I have chosen to reference the artist’s correct surname. ↵

- See, for example, the award-winning PBS documentary Tyrus, directed by Pamela Tom (New Moon Pictures, 2015). Tyrus Wong and Michael Labrie, Water to Paper, Paint to Sky (Richmond, CA: Weldon Owen, 2013), the catalogue for a retrospective mounted by the Disney Family Museum in 2013; and “Memories: Tyrus Tells His Story,“ a chapter written in Wong’s voice in the bestselling book by novelist Lisa See, On Gold Mountain (New York: St. Martin’s Press 1995). See’s grandfather was Wong’s close friend. ↵

- Some of Wong’s top-selling cards include “Enchanted Forest” (1955), “Holy Miracle” (1956), “Wintry Vista” (1957), 45-6804-R7 (1958), 609 (1959), all from California Artists, and “The Nativity” (1961), “The Offering” (1962), and “The Guiding Star” (1963) from Duncan McIntosh. ↵

- Wong’s unusually long life and career encompass multiple venues and documentary sources. Although he was the subject of a retrospective study as early as the mid-1960s, when he was interviewed in 1965 as part of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art (SAAA) oral history project with surviving veterans of Roosevelt’s Federal Art Project, cultural and scholarly interest in Wong himself did not begin until the 1990s, when he appeared in See’s On Gold Mountain and in Disney animators Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas’s book, Walt Disney’s Bambi: The Story and the Film (New York: Tabori, Stuart and Chang, 1990). The latter book emphasizes Wong’s role in the movie, Around this same time, Disney and animation historians such as Michael Barrie, John Canemaker, and Charles Solomon reached out to Wong, leading a rediscovery that led to the film documentary, several museum retrospectives, an award-winning children’s book–Julie Leung with Chris Sasaki, Paper Son: The Inspiring Story of Tyrus Wong, Art and Immigrant (New York: Schwartz and Wade, 2019)–and even a Google Doodle. Yet while these contexts emphasize Wong’s Disney and Exclusion history, the artist included nine copies of his greeting cards in the collection of images accompanying his SAAA oral history. Tyrus Wong, oral history interview with Betty Hoag, January 30, 1965, SAAA. ↵

- Beyond literary scholar Barry Shank’s critical history of greeting cards, A Token of My Affection (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), one of the few recent book-length studies of greeting cards is Patrick Regan‘s commissioned Hallmark history, A Century of Caring (Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2009). ↵

- Tyrus Wong interview with Eddie Wong, February 22, 2010, Angel Island Resource Center; and Tyrus Wong interview with Gilbert Leong, January 8, 1992, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. Wong was inducted as a Disney Legend in 2001. ↵

- Mark Johnson interview with Pamela Tom, on about October 25, 2008, typescript courtesy Pamela Tom; and the exhibition, With New Eyes: Toward an Asian American Art History in the West, Fine Arts Gallery, San Francisco State University Gallery, September 24–October 26, 1995, curated by Johnson, Irene Poon Anderson, Dawn Nakanishi, and Diane Tani. ↵

- Suellen Cheng to the author, December 7, 2018. ↵

- Although the term Asian fusion is most commonly used for cuisine, many scholars, collectors, and curators use fusion to describe Wong’s blend of cultural-aesthetic references. ↵

- Birds are probably Wong’s single-most recurring subject. Each year, his new series included at least one or two images in which a perched bird executed in Wong’s signature brushwork with negative space is the primary compositional subject. By the mid-1960s, their number in each series increased to three or four. Including other bird designs done in different styles, birds represent 10 percent of his designs. ↵

- Of the 457 cards in surviving display albums, 393 cards (86 percent) are signed. ↵

- Wong’s visual play in rendering his signature also reflects the multiple, conflicting identities imposed by Exclusion as well as how Chinese Americans reinvented themselves in light of those conditions. The name “Tyrus Wong” is a compound of the artist’s real family name, Wong, and a Latinized version of the paper name Tai Yow, with which Wong entered the United States. (Wong’s actual Chinese name was Wong Gen Yeo, and his paper name was Look Tai Yow.) Similarly, Dong Kingman was born Dong Moy Shu, but adopted “Kingman” as his given name after being given that name by his Paris-trained, Hong Kong–based instructor, Szeto Wai. ↵

- Tyrus Wong contract with Looart Press on November 1, 1974, Wong family papers. ↵

- Tyrus Wong to Eugene C. Hall, Hallmark, June 24, 1964, Hallmark Archives. ↵

- Duncan McIntosh album, 1961, and California Artists album, 1958, Wong family estate. ↵

- First International Exhibition of Etching and Engraving, exh. cat (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, March 24–May 15, 1932; International Exhibition of Contemporary Prints: A Century of Progress, exh. cat. (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, June 1-November 1, 1934. ↵

- Arthur Millier, “Brushstrokes,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1937; and “Young, Older Artists Aided by Federals,” Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1937. ↵

- “Occidental Training Modifies Chinese Skill,” Los Angeles Times, July 30, 1939. Probably authored by Arthur Millier. ↵

- Elizabeth Fuller Jones, “Chinese Family Welcomed in U.S. Community,” Christian Science Monitor, November 26, 1957. ↵

- Christina Klein, Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). In a further parallel between Wong and Dong Kingman, Dong too benefitted from Hollywood’s postwar Sinophilia, doing special artwork and titles for The Sand Pebbles, Flower Drum Song, and 55 Days at Peking. ↵

- Frances Rockwell, “Come Bomb My Kailing,” Western Family, January 6, 1944, 4–5ff. ↵

- Vanya Oakes, Footprints of the Dragon (Philadelphia, PA: John C. Winston Company, 1949). ↵

- Bill Stern, Mid-Century Mandarin: The Clay Canvases of Tyrus Wong, exh cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of California Design, 2004). ↵

- Tyrus Wong interview with Pamela Tom, April 26, 2001, transcript courtesy Pamela Tom. ↵

- Duncan R. McIntosh, California Artists director, to artists of California Artists, August 4, 1952, Wong family papers. ↵

- Amid Amidi, “The Beautifully Designed Christmas Card Art of Animation Legend T. Hee,” Cartoon Brew, December 25, 2017, https://www.cartoonbrew.com/illustration/beautifully-designed-christmas-card-art-animation-legend-t-hee-155515.html. ↵

- California Artists album, 1958, 1, Wong family estate. ↵

- Duncan McIntosh album, 1961, 1; and Duncan McIntosh album, 1967, 1, Wong family estate. ↵

- California Artists, for example, required submissions by October 1 of the preceding year, Hallmark by November 1, and Duncan McIntosh by December 1. Duncan McIntosh, California Artists director, to its artists, August 4, 1952, and Artist Guidelines, 1955, Wong family papers; Tyrus Wong contract with Hallmark June 11, 1963, Hallmark Archives; Tyrus Wong contract with Duncan McIntosh, Feburary 8, 1960, Wong family papers. Wong said he did most of his designs in June and July (Wong interview with Tom, April 26, 2001). At the very end of Wong’s greeting card career, the Colorado publisher Looart—with whom Wong worked in 1975 and 1976—did not require new designs until February of the year the cards would appear, but printing processes were much faster and Wong had a considerable body of past designs for reissue. See Looart contract, Wong family papers. ↵

- Duncan McIntosh required twenty-four designs (see contract February 8, 1960, Wong family papers), out of which the corporation promised to publish at least twenty. During Wong’s Hallmark collaboration (1964–66), he was contracted to create twenty-five card designs, from which the brand selected a minimum of twenty to publish. Looart only requested twenty. See Hallmark contract, Hallmark Archives, and Looart contract, Wong family papers. ↵

- Warner Club News, December 1957, 2; January 1958, 1; December 1958, 10; and February 1960, 4. ↵

- Hallmark archivist Samantha Bradbeer to the author, July 9, 2018. ↵

- In 1952, prices for personalized cards ranged from $6.75 to $10.75 per twenty-five cards (unpersonalized boxes ranged from $3.75 to $6.25). Bullock’s advertisement, Los Angeles Times, November 7, 1952. ↵

- Wong’s most common religious subject is the flight of the Holy Family, which he portrayed over nearly forty discrete images. ↵

- Wong interview with Tom, April 26, 2001. ↵

- For the 1952 musical She’s Working Her Way through College, Wong studied photo references for an Egyptian number in the film’s finale. Not much of the motif survives in the film’s final cut, but Wong possibly drew on that experience when painting “Sheltering Sphinx,” a 1964 Hallmark card that is notable for its referential specificity. Research department request, Tyrus Wong, November 8, 1951, production file for She’s Working Her Way through College, Warner Bros. Archives. ↵

- Hallmark archivist Samantha Bradbeer to the author, July 9, 2018. ↵

- Other repeat images include “A Snug Nest” (Duncan McIntosh, 1968, repeated Metropolitan 1973); “Winter Landscape” (Metropolitan, 1970, repeated 1975); and “Woodland Fantasy,” “Soaring Trees,” and “Bird at Peace” (all Metropolitan, 1972, repeated 1975). In addition to “Winter Guest,” in 1965, Hallmark also repeated Wong’s 1964 monochrome “The Chapel.” ↵

- Unsigned designs and other images marketed as part of an imprint’s general collection customarily paid a 5 percent royalty. Samantha Bradbeer to author, July 9, 2018. ↵

- At Hallmark, Wong had a $250 advance, “charged against sales,” and a “high royalty rate of ten percent,” which was among the higher end for artists. Tyrus Wong Hallmark contract, June 11, 1963, Wong family papers; Hallmark to Louis G. Frye, February 24, 1966, Hallmark Archives. Among Hallmark’s other artist contracts at that time, a royalty rate of 5 percent was more common. Hallmark archivist Samantha Bradbeer to the author, July 9, 2018. ↵

- Kay Fong interview with Pamela Tom, April 16, 2015, transcript courtesy Pamela Tom. ↵

- The $14,500 was promised regardless of his actual royalties. ↵

- One hundred dollars was the typical price publishers paid to purchase the original artwork. ↵

- With California Artists, Wong was “entitled to receive 50 free cards of each of your published designs.” Don Woolf (Art Director, California Artists) to Tyrus Wong, August 24, 1966, Wong family papers. Looart gave one hundred copies of each of the artist’s selected own designs; see Looart contract, Wong family papers. ↵

- Original art for the greeting cards Wong sold or donated include “Christmas Bird” (California Artists, 1956), exhibited in 1959 and donated to Pacoima Lutheran Hospital in 1962, and “The Offering” (Duncan McIntosh’s bestselling card for 1962), sold in 1966 to a “Mr. Holzman of the National Cash Reg. Co.” Ruth and Tyrus kept careful notes regarding the original art and complimentary editions. Within the display albums Ruth would note on each page when the original art was returned from the printer and any subsequent exhibition or sale of the work; within the Wong family papers are lists by Ruth and Tyrus noting the styles they requested and to whom they gifted complimentary cards. ↵

- Ken Barmore to Tyrus and Kim Wong, March 18, 2014, Wong family papers; Ann DiCiano to Kim Wong, April 29, 2020, Wong family papers. Wong and the Barmores exchanged holiday greetings for decades, and today that couple’s children and grandchildren still cherish the Wong paintings. ↵

- Mrs. Sherman L. Black to Tyrus Wong, December 9, 1964, Wong family papers; and Wong to Black, December 14, 1964, Wong family papers. ↵

- In fact, greeting cards—and illustration more generally—are still so overlooked by traditional disciplinary standards that neither term is among the existing “Areas of Specialization” identified by the Association of Historians of American Art for its membership profiles. Similarly, neither term was included among the tags on Panorama’s website before publication of this article; “illustration” and “commercial art” have since been added. ↵

- Robert Indiana’s famous LOVE composition began as a holiday card for the Museum of Modern Art in 1965; see excerpt from an essay by Judith Hecker, in Deborah Wye, Artists and Prints: Masterworks from The Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 166, on the museum’s website, accessed May 27, 2021, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/68726. Norman Rockwell and Grandma Moses also had highly successful greeting card lines, but because their styles had more obvious overlap with the sentimental imagery and style of illustration commonly associated with greeting cards their industry collaboration may seem less striking. Katherine Jentleson and Jane Kallir, “From Gallery to Greeting Card: Copyrighting Grandma Moses,” Art Journal 76, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 90–94. ↵

- Ayesha K. Hardison, “Why Maya Angelou Partnered with Hallmark,” Humanities 42, no. 1 (Winter 2021): 10. ↵

- Longtime Hallmark art director Jacqueline Lee was known for actively seeking artists all over the world, and Wong’s Hallmark collaboration in the mid-1960s coincided with a time when the company was particularly internationalist. See Regan, A Century of Caring, 148–49, 166. ↵

- Tyrus Wong, American Visual History interview with Michael Mallory, August 11, 2015, Academy Visual History Collection, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. ↵

- Sonia Mak to the author, December 7, 2018. ↵

- Wong interview with William Gow, October 6, 2007, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. ↵

- The exceptions are two designs from early in Wong’s career: “Candy Cane Forest” and “Ornaments,” both for California Artists in 1955, which feature a miniature Santa. ↵

About the Author(s): Karen Fang is Professor in the Department of English, University of Houston