Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene

Diana L. Linden

Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2015; 184 pp.; 61 illus.; ISBN: 9780814339831; Hardcover: $44.99

In 1906, when Ben Shahn and his family arrived at Ellis Island, the United States was still a nation welcoming masses of immigrants to its shores. Shahn was eight years old at the time, and embraced his identity as an American. He soon discovered, however, that this was by no means a straightforward task. As Shahn reached adulthood, the United States stopped being so welcoming. Nativist politicians clamped down on immigration with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, anti-Semitic fascists rose to power in Europe, and Jews in America became more visible, political, and vulnerable. Immigrant artists such as Shahn made careful choices about how to define and represent their communities, identities, and ideologies while creating public art during the New Deal era.

In 1906, when Ben Shahn and his family arrived at Ellis Island, the United States was still a nation welcoming masses of immigrants to its shores. Shahn was eight years old at the time, and embraced his identity as an American. He soon discovered, however, that this was by no means a straightforward task. As Shahn reached adulthood, the United States stopped being so welcoming. Nativist politicians clamped down on immigration with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, anti-Semitic fascists rose to power in Europe, and Jews in America became more visible, political, and vulnerable. Immigrant artists such as Shahn made careful choices about how to define and represent their communities, identities, and ideologies while creating public art during the New Deal era.

In Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene, Diana Linden analyzes four mural projects in which Shahn articulated the strands of American and Jewish experience and intellectual life that he chose to celebrate and critique. Aided by extensive archival documentation, Linden’s work sheds new light not only on Shahn’s particular self-definition, but also on the external forces that shaped his options. In some cases, Shahn made accommodations for the sake of politics, while in other cases, he refused. By focusing on the artist’s agency in moments of negotiation, Linden helps us see him on his own terms, and the American scene in its full mix of glory and horror. Numerous glossy color illustrations—including historic and modern views of Shahn’s mural projects, details, photographs, archival sources, preparatory studies, and comparative works—beautifully enrich the telling of these stories by Linden. Wayne State University Press should be commended for producing such a beautiful book.

In a 1998 essay published on Shahn’s murals and Jewish identity, Linden surveyed earlier scholarly debates about the artist and announced that in contrast to other academics, she was not going to debate “’how Jewish’ Shahn was” but instead “demonstrate how his murals speak about secular Jewish immigrant experiences in America during the early twentieth century.”1 Nearly twenty years later, Linden’s approach has evolved. She now situates Shahn’s experiences within the larger lens of American racism, through which waves of newcomers were viewed and evaluated against enduring and evolving prejudices and power structures. Within this schema, Linden views immigrant American Jews in Shahn’s era as peripheral “in-between peoples.” (5) Clearly, she has been reading up on critical race theory, to the benefit of her project. Her achievement in balancing Shahn’s idiosyncratic particulars within the framework of this larger structure offers a model for all of us who write monographic studies.

Linden begins her account of Shahn with an overview of the persistent, terrifying, and violent anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe that caused Jews to flee to America. After their arrival from Lithuania, the Shahn family settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which must have felt somewhat like home given its high percentage of Jewish residents; Shahn’s identification with this community was unshakeable.

As a young artist, Shahn quickly fell in with activists within the American Scene movement, joining organizations such as the Artists Union, and working for New Deal arts programs including the Resettlement Administration/Farm Security Administration (RA/FSA) photography program. Although Linden does a fine job providing an early biography of Shahn, the bulk of her book is focused on the years between 1933 and 1943. In the first chapter, “Ben Shahn’s New York and the Great Depression,” she provides a brief but effective introduction to a “Multiracial City” in the throes of economic distress. Accounts of Fiorella LaGuardia, the Jewish Daily Forward, anti- and pro-Nazi demonstrations, Shahn’s first wife Tillie Goldstein, Diego Rivera, and a variety of left-leaning artists’ organizations concisely set the stage for the mural projects Linden describes in following chapters.

Shahn’s relationship with Diego Rivera is particularly important. The famed Mexican muralist introduced his young apprentice to “authentic fresco painting,” as well as his future (second) wife, Bernarda Bryson. Equally consequential was Nelson Rockefeller’s decision to destroy Rivera’s mural commissioned for his new Rockefeller Center, Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future in 1934. The incident proved to be a formative experience for Shahn in protesting against art censorship. As Linden summarizes, the two artists were united in “their shared commitment to creating political art in order to stir the masses into revolutionary action.” (28–31) This aim did not always please the government administrators and corporate capitalists who paid the bills.

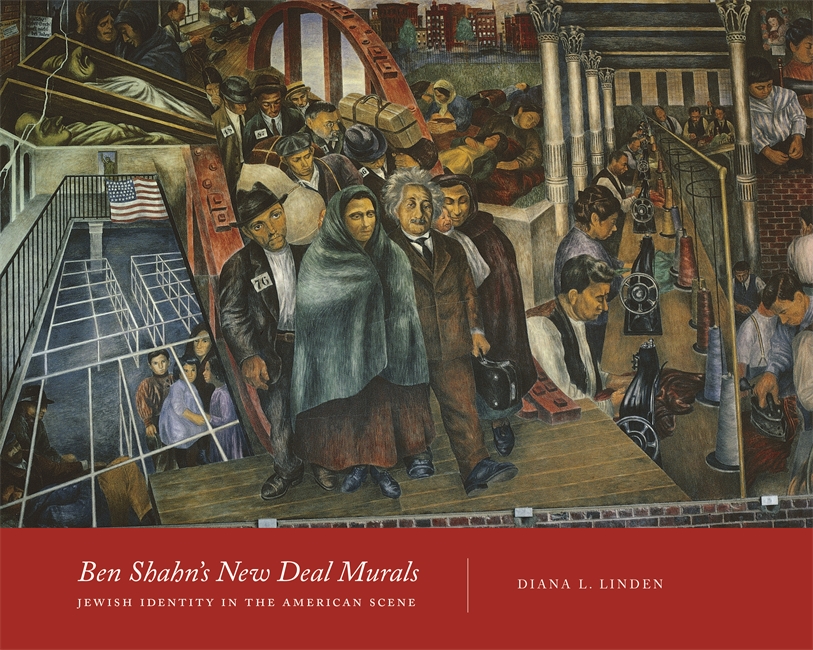

In the second chapter, “Zion in the Garden State: Ben Shahn’s Mural for Jersey Homesteads,” Linden discusses Shahn’s artistic contribution, from 1936 to 1938, to a newly-built “Jewish agro-industrial community” in which farming and garment production were undertaken communally. (36) The business side of things failed both miserably and rapidly, but the homes survived, and Shahn and his new wife Bernarda Bryson moved in. The couple spent their lives in the good company of one of Shahn’s most cohesive and uplifting works.

As Linden details with particular attention to both subject and form, Shahn painted a three-part story at the Jersey Homesteads: Jewish immigrants arriving in America, organizing garment worker labor unions, and then planning their utopian Jersey community. Authors including Frances Pohl have analyzed the labor union politics in the mural profitably, and here Linden adds to our understanding of the work by turning instead to the history of Jewish farmers in the United States and their connections with Soviet Marxists.2 She also provides an in depth account of the politics behind the construction of the Homesteads, with its rich mix of labor organizers, families seeking to escape unhealthy living conditions in the city, and New Deal administrators eager to support collective (and segregated) efforts.

The portrait Linden paints of the Jersey Homesteads, and Shahn’s mural there, illustrates Jewish Left intellectual life in the 1930s as both aspirational, and desperately anxious. Although the mural overall conveys pride and an optimistic outlook on the future, dark figures loom as well. In the upper left corner, Shahn painted the dead bodies of the Italian immigrants Sacco and Vanzetti, who were tried and condemned to death via a sham trial tainted by nationalist xenophobia. A Nazi soldier stands behind their coffins, sporting a sign that declares (in German): “Germans! Defend Yourselves! Don’t shop from Jews!” (54) Shahn and his circle were activists as much as artists, and they were keenly attentive to an exploding landscape of both national and international threats.

In Linden’s next chapter, “Whitman, Workers, and Censorship: Ben Shahn’s Murals for the Bronx Central Post Office,” we get to see what happened when Shahn faced the cultural headwinds of his time. It was one thing to extol the labor movement and immigration in a mural for a socialist utopia populated almost completely by Jews. It was quite another thing to paint from that perspective in a federal post office, under the direction of Washington bureaucrats.

Linden begins her discussion of Shahn’s Bronx murals, painted from 1938 to 1939, by carefully relating them to her theme. Although the subject matter in the Bronx was not overtly Jewish, Shahn’s ethnic identity was important in shaping his ensuing struggles. As World War II loomed, the contradictions within the city were brutally evident. From Shahn’s studio in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, he could watch parades of German Americans dressed in Nazi military regalia. Uptown in the Bronx, where his new commission was located, American Jews had moved en masse into newly-built cooperative housing, once again expressing their communal affiliation and leftist political bent.

In his enormous, thirteen-panel mural series for their neighborhood post office, Shahn depicted Resources of America—views of (mostly male) factory and agricultural laborers. Linden points out that Shahn did not attempt to include Jews in the downtown garment industry, or African American domestic workers who waited for employment in the so-called “Bronx Slave Market” in his panels. (71) More could be said here about this exclusion. Shahn’s declared intention to introduce Bronx residents to workers outside the city is not wholly convincing. Is it possible that he did not conceptualize these New York laborers as fully American rather than alien “resources,” based on his own feelings of alienation? Did New York itself seem somehow less than fully American? Or, was Shahn unwilling to risk those conversations with administrators?

Another small point here is that Linden could take better advantage of some excellent scholarship on Shahn’s photography. During the years he was painting the murals Linden so beautifully analyzes, Shahn also took thousands of photographs for the Historical Section of the RA/FSA. Laura Katzman has surveyed Shahn’s extensive files of source materials, including pictures cut from newspapers and magazines, as well as his own photographs, as evidence of an artist for whom photography and politics were “inextricably linked.”3

What really animates and distinguishes Linden’s take on Resources of America is her patient untangling of the battle Shahn fought and lost regarding censorship. Although his mammoth workers were not at all controversial, Shahn included a portrait of Walt Whitman accompanied by his poem “I Hear America Singing,” which included the lines: “Brain of the New World, what a task is thine, / To formulate the Modern—out of the peerless grandeur of the modern, / Out of thyself, comprising science, to recast poems, churches, art.” (86–87) In the imagination of conservative Catholics, Whitman was the intellectual father of godless Communists, and this quote was a patent example of the poet’s virulent agnosticism. Linden carefully relates the public controversy and administrative pressure directed at Shahn that followed. Once again, what emerges is a full display of the toxic mix of competing and conflating prejudices and radical ideologies in public debate during these years. In the end, Shahn caved, and chose a less controversial Whitman poem to include. As Linden summarizes, the artist’s “desire to secure and advance the project was greater than his desire to do battle for the verboten.” (91) In moments such as this, character is tested, under force. But character is not made in a day, and Shahn determined more than ever to make the First Amendment his cause in the future.

In the last mural projects Linden describes in chapter four, “Painting for Freedom and the Freedom to Paint,” Shahn’s stiffened resolve to defend First Amendment rights is entirely evident. Linden first discusses Shahn’s proposed mural designs drafted for the main branch of the St. Louis post office in Missouri in 1939. The rejection of Shahn’s proposal is little surprise. The guidelines called for an historical account of “the transportation of the mails in the area of St. Louis,” but Shahn proposed panels including “Freedom of Religion,” “Freedom of Speech,” “Freedom of the Press,” and two views of “Immigration” expressing “his outrage at the mounting refugee crisis.” (108) Once again in this chapter, Linden masterfully frames close readings of Shahn’s subject matter and formal choices within rich context, including here the Jewish Labor Committee, the 1938 pogrom Nazis euphemistically called Kristallnacht, the shameful refusal of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to welcome Jewish refugees, the polemics of Father Charles Coughlin, the rise of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and the tragedy of the MS St. Louis. Shahn’s subsequent commission for the Woodhaven branch post office in Queens, New York, in contrast, went smoothly, and he completed a glorious celebration of The First Amendment there in 1941, with the Statue of Liberty at center. In St. Louis, as well as in Queens, he did not give any ground. In the heightened terrors of 1939 to 1941, it must have felt like compromise no longer was an ethical option.

Linden concludes her book with a return to ruminations on the meaning of the term “Jewish artist.” She relates Shahn grappling with this label, and in comparison, the scholarly “packaging” of Mark Rothko. Serving as moderator, Linden introduces a scholarly dialogue across generations, including Harold Rosenberg, Samantha Baskind, Larry Silver, Sander Gilman, and Susan Glenn. Her greatest contribution here is her consideration of Shahn on the larger American stage. Ultimately, what made Shahn’s experience so deeply American was his enduring identity as an immigrant. His view from the periphery brought a heightened awareness of the political opportunities and liberties afforded here as compared with Europe. As an immigrant American and a New Yorker, he idolized the possibilities of this nation, whose welcoming embrace was written into the First Amendment and visualized by a glorious evocation of Liberty at the nation’s metaphorical front door.

In her analysis of Shahn’s New Deal murals, Linden shows us just how important this voice from the periphery is, with its heightened capacity to critique and call out the contradictions between our rhetoric and reality. It is sad to think how clearly Ben Shahn would recognize the forces at play in our present moment. If it is any consolation, his example certainly is a guide to what many will do in the face of longstanding and persistent tyrannies: organize, protest, and make art with energy and passion that loudly calls on this nation to once again be welcoming and free.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1597

PDF: Werbel Review of Diana L. Linden, Ben Shahan’s New Deal Murals

- Diana L. Linden, “Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene,” in Susan Chevlowe, ed. Common Man, Mythic Vision: The Paintings of Ben Shahn, exh. cat. (New York: The Jewish Museum in association with Princeton University Press, 1998): 37. Susan Noyes Platt also has written about the Jersey Homestead murals, summarizing in 1995 that they represent a “conflation of personal memory, personal experience, and received history,” stylistically influenced by Diego Rivera, Thomas Hart Benton, as well as his own photography. Platt briefly mentions the shift in Shahn’s plan for the murals, following WPA insistence, from an emphasis on distinctive Jewish characteristics among settled Americans, to a scene that showed Jews “blending into the American scene.” See Susan Noyes Platt, “The Jersey Homestead Murals: Ben Shahn, Bernarda Bryson, and History Painting of the 1930s” in Patricia M. Burnham and Lucretia Hoover Giese, eds., Redefining American History Painting (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995): 302–3. ↵

- Frances K. Pohl, Ben Shahn: New Deal Artist in a Cold War Climate (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989). ↵

- Laura Katzman, “The Politics of Media: Painting and Photography in the Art of Ben Shahn,” in Deborah Martin Kao, Laura Katzman, and Jenna Webster, Ben Shahn’s New York: The Photography of Modern Times, ex. cat. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000): 106. See also Laura Katzman, “Source Matters: Ben Shahn and the Archive” Archives of American Art Journal 54, no. 2 (Fall, 2015): 4-33. In future projects, Linden may also wish to consider some broader commentary on aesthetic strategies evident in other Jewish muralists painting in the 1930s, such as Philip Evergood and Joseph Hirsch. In a new book published in 2015, Matthew Baigell briefly discusses, for example, Philip Evergood’s The Story of Richmond Hill, 1936–37, painted for the Richmond Hill Branch Library in Queens, and Joseph Hirsch’s murals for the Philadelphia Joint Board of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America installed in the Sidney Hillman Apartments in Philadelphia in 1936. Matthew Baigell, Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art, 1880–1940 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2015): 173–80. ↵

About the Author(s): Amy Werbel is Associate Professor of the History of Art at the Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York.