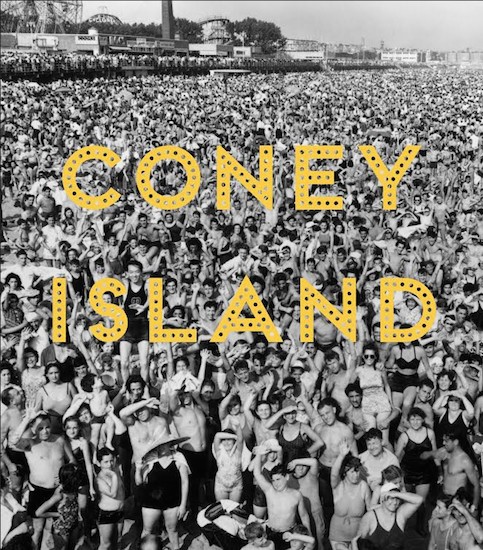

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861-2008

Robin Jaffee Frank, with Charles Denson, Josh Glick, John F. Kasson, and Charles Musser

Exh. cat. Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015; 304 pp., 228 color + 77 b/w illus.; $50.00 (hardcover); ISBN: 9780300189902

Exhibition schedule: San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, California, July 11, 2015 – October 13, 2015; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York, November 20, 2015 – March 13, 2016; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas, May 11, 2016 – September 11, 2016.

Recent American art publications and exhibitions increasingly have engaged multimedia projects that dissolve many previous constraints on mingling painting and sculpture with popular art and visual culture. Coney Island, New York City’s “playground of the people,” serves as the perfect subject for such a study. Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861-2008 addresses the artworks and amusements produced by the proprietors and eager visitors of this well known American site of urban recreation. While the exhibition’s curator Robin Jaffee Frank, and contributing authors, Josh Glick, John F. Kasson, and Charles Musser, divide the book loosely by medium and time period, the reoccurring thread that unites this catalogue is the interaction between class, gender, and ethnicity represented in equally diverse examples of art and culture. Charles Denson contributes a unique voice by reminding readers of the ongoing importance of Coney Island and the ways in which it continues to change dramatically in the seven years since the catalogue’s chronological conclusion (2008). The catalogue succeeds in presenting beloved artworks, such as Reginald Marsh’s large body of Coney Island paintings, while complicating our understanding of them through well-written essays and judiciously selected images that widen the reader’s understanding of the larger context within which they were created. Each of the authors writes broadly about shifts in American society and culture, but remains grounded in precise discussions of specific works of art, thereby providing a worthy model for exhibition catalogues.

Recent American art publications and exhibitions increasingly have engaged multimedia projects that dissolve many previous constraints on mingling painting and sculpture with popular art and visual culture. Coney Island, New York City’s “playground of the people,” serves as the perfect subject for such a study. Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861-2008 addresses the artworks and amusements produced by the proprietors and eager visitors of this well known American site of urban recreation. While the exhibition’s curator Robin Jaffee Frank, and contributing authors, Josh Glick, John F. Kasson, and Charles Musser, divide the book loosely by medium and time period, the reoccurring thread that unites this catalogue is the interaction between class, gender, and ethnicity represented in equally diverse examples of art and culture. Charles Denson contributes a unique voice by reminding readers of the ongoing importance of Coney Island and the ways in which it continues to change dramatically in the seven years since the catalogue’s chronological conclusion (2008). The catalogue succeeds in presenting beloved artworks, such as Reginald Marsh’s large body of Coney Island paintings, while complicating our understanding of them through well-written essays and judiciously selected images that widen the reader’s understanding of the larger context within which they were created. Each of the authors writes broadly about shifts in American society and culture, but remains grounded in precise discussions of specific works of art, thereby providing a worthy model for exhibition catalogues.

Exhibition curator and primary catalogue author Robin Jaffee Frank wastes no time in introducing a central theme of the catalogue, by quoting Reginald Marsh on Coney Island in her Acknowledgments: “The best show is the people themselves.” (xiv) John Kasson adopts this theme in the catalogue’s first essay, “Speculating at Coney Island.” Author of the influential Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century (1978), which still resonates today as an important model for cultural studies, Kasson presents Coney Island as a laboratory for American social and cultural experimentation. Describing the development of Coney Island’s amusement parks at the turn of the century, he finds particular interest in entrepreneurs who reimagined these temples of entertainment as visions of American potential. From its early years, even the rides at Coney Island turned a visitor’s attention to their fellow visitors. At George Tilyou’s Steeplechase Park, one of several private amusement parks that populated Coney Island, visitors exited the park’s main attraction though the “Blowhole Theater,” where concealed air jets blew up women’s skirts and clowns besieged male visitors with an electric cattle prod. After surviving this entertainment, visitors would pause in the Laughing Gallery, where they watched the next wave of victims make their way through the attraction. This is only one of many such attractions that Kasson and the others elucidate as key to understanding the draw of Coney Island. Below the electric lights and extravagant architecture, the main spectacle at Coney Island was the people themselves. As such, social and racial barriers eroded through the transgression of boundaries that may have otherwise separated people. Many artists were keen to explore this, depicting the swirling attractions and crowds that seemed unique to Coney Island.

The following five essays, all written by Robin Jaffee Frank, break down the almost 150-year span of the catalogue into distinct eras. The first traces Coney Island from a site of natural refuge to its rapid development just prior to the turn of the twentieth century. Beginning in 1869, a train provided service between New York City and the beach destination. Paintings by Sanford Robinson Gifford, Francis Augustus Silva, and the enigmatic Samuel S. Carr define this first era of artistic production. While Gifford’s long, tonal beaches strike a familiar chord, one senses the creeping influence of this new amusement destination. Likewise, in Carr’s scenes of fashionably dressed people posing on the beach, Frank rightly notices the casual, almost unremarkable mixing of social classes and ethnicities that took place at Coney Island. Finally Frank examines beachfront photography and its depiction in painting, such as in Carr’s Beach Scene (ca. 1879), which pictures a posed family, photographer, and cadre of onlookers. For Frank, these surreal tableaus indicate the ways in which tourists themselves become a part of the visual spectacle of Coney Island. In addition, these early Coney Island artworks hint at the uncanny lying just beneath the surface. For example, William Merritt Chase’s Landscape, near Coney Island (ca. 1886) bears all the recognizable elements of his later Shinnecock paintings, yet unsettlingly includes a colossal elephant rising above the horizon. The 122-foot-high Elephant Hotel was known for prostitution. Yet as Frank argues, in this period Coney Island remained a locus for restful leisure, a salve for the troubles of the workweek. It would be future generations that came there to highlight and celebrate the grotesque.

Frank’s second essay “The World’s Greatest Playground,” covers the years 1895-1929, an era when the growth of Coney Island accelerated and it became a destination for amusement and dissolution. Introducing the visual and material culture of Coney Island, including postcards, broadsides, carved signs, and other ephemera, for Frank the gleefully broad smile of the Steeplechase Funny Face, an iconic sign that welcomed visitors to Steeplechase Park for decades, personified Coney Island’s air of mischievous libidinousness. Frank quotes one commentator describing Coney Island as, “an orgiastic escape from respectability—that is, from the world of What-we-have-to-do into the world of What-we-would-like-to-do.” (36) Finally, Joseph Stella’s Battle of Lights, Coney Island is placed in conversation with George Bellow’s Beach at Coney Island and Abraham Walkowitz’s Side Show at Coney Island. Buildings and bodies twirl and lurch in these renderings, mimicking the dragons and carved animals found along the boardwalk. This fantastic environment provided an escape from the routine of the work week and the drudge of home life. With the increased inclusion of new immigrants and women into the urban workforce, Coney Island also reflected expanding social values, where men, women, and children of varied races and social classes freely mixed.

In “The Nickel Empire,” Frank examines the lasting effects of the Great Depression on Coney Island throughout the 1930s. A landmark 1938 essay in Fortune magazine coined the phrase, “To Heaven by Subway,” a continuation of the theme of Coney Island as both otherworldly and for the masses, the “Poor Man’s Riviera.” (79) At the center of this chapter is Reginald Marsh’s significant body of paintings and drawings created from direct observation at Coney Island. Frank focuses on Marsh’s interest in the teeming crowds. Ever the observer of the human body, Marsh’s paintings exuded lurid sexuality and depicted both sideshow performers and the different types of people frequenting these visual attractions. Significantly Frank includes Marsh’s own reference photographs taken at Coney Island, as well as extant advertisements meticulously featured in his paintings, to contextualize these artworks. Throughout this essay, paintings and photographs of sideshow ‘freaks’ and beauty contestants are interwoven with artists’ depictions of half-dressed people of all body types on the beach. For example, Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s bird’s-eye views of beach goers capture both sensuality and danger. While Frank’s interest in the human body as subject is limited only to artworks of Coney Island, the aesthetics of the ‘irregular’ body, especially exhibited in popular amusements, extended far beyond Coney Island and has deep roots in American racial and cultural politics.

Frank’s final two chapters, “A Coney Island of the Mind, 1940-1961” and “Requiem for a Dream, 1962-2008,” deal with a Coney Island of memory, where an imagined past glory is upset by a disquieting reality. The photographs of Weegee and the magical realist paintings of George Tooker define the broad contours of Frank’s discussion, in which the uncanny nature of Coney Island is no longer an experiment for an undefined future, but rather has become the memory of an age of possibility. The beach bathers, the spectators, and the families loitering on the boardwalk appear as dislocated figures within the crowd, no longer a part of the great masses mingling in exuberant defiance of social norms. Tooker’s Coney Island (1948) expresses the same interest in figural form and social and racial mixing that Marsh and Paul Cadmus celebrated in the interwar period. Yet Tooker’s signature isolation of figures presents an alien landscape, where the figures hide themselves from the sun beneath the boardwalk. Frank carries her discussion of Coney Island through the end of the twentieth century, as the dreamland of Coney Island continued to unravel into a dystopian landscape, countering the memory of opportunism that once enveloped the park. Yet, artists continue to return to this unique place in American culture. Frank persuasively asserts that over the past 150 years, despite its rise and fall in popularity, Coney Island has been a conduit for the human imagination and a vision for the possibilities of the future, for better or for worse.

The next four essays in the catalogue are dedicated to the concurrent rise of film during the period in question and the medium’s inseparable relationship with Coney Island. One criticism towards the overall organization of the catalogue itself is that, after Kasson’s brief overview and Frank’s more detailed essays, this section provides the third time that the reader has been through the chronological development of Coney Island and its related cultural productions. Frank’s previous essays touched upon many of the key moments in film history that provided unique insight for her discussions of Coney Island. Each of those examples are again repeated in the following essays. Perhaps a more concentrated approach to grouping the essays, even in lieu of co-authored ones, would have provided the reader with greater clarity and an understanding of the many artists working alongside one another at any given point in the project’s vast chronology.

Those criticisms aside however, Josh Glick and Charles Musser’s essays offer compelling introductions to film and photography at Coney Island. For readers who may come from a more rigid art historical background, this is refreshing. Yet, unfortunately they can also feel like case-study addendums in contrast to Frank’s sweeping surveys. Like Frank, Glick and Musser identify an early interest in spectatorship at Coney Island, but situate it within the expanded role of film, which offered a “prosthetic experience” for viewers who did not have to visit Coney Island to experience it. (204) Indeed, one of the most interesting subjects captured on film by Thomas Edison’s company was the gruesome execution by electrocution of the unruly elephant Topsy. While discussions of race pervades this text, the authors do not note the connection between this famous elephant and Topsy from Uncle Tom’s Cabin.1 In spite of this oversight, Glick and Musser revisit Weegee’s photographic works at Coney Island, along with later filmic romanticized views of Coney Island, such as Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) and Sidney Lumet’s The Wiz (1978). Josh Glick brings his discussion up to the present, arguing that Coney Island continues to inspire filmmakers, and that their relationship with the city continues to change as the site itself experiences a cultural resurgence.

In a very refreshing coda, a Coney Island local and director of the Coney Island History Project delivers a brief, personal overview of his relationship with the city, its current condition, and the prospects for the future. Charles Denson addresses many issues that are briefly referred to throughout the essays, particularly current threats to Coney Island spearheaded alternately by Robert Moses and Fred Trump. Despite the fact that the catalogue is very clear about its chronological purview of 1861-2008, it is difficult to read about the development and renewal of Coney Island without thinking about 2012’s Hurricane Sandy or the current threat to Coney Island as the “anti-Disney” “antidote to a sterilized, corporate Times Square.” (260-61) Indeed, after the catalogue’s whirlwind tour through the cultural history of Coney Island, it appears that its ever-changing nature seems to be its one defining constant. Denson himself notes that even in 2014, as its future remained contested, Coney Island will continue to adapt and inspire.

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861-2008 provides a useful model for a multimedia, holistic examination of a single topic that touches upon multiple facets of American social and cultural history. It therefore has value as a thorough and multifaceted examination of this archetypal American city of amusement and dreams. While an examination of Coney Island might have benefited from the inclusion of similar ventures, such as the Palisades Amusement Park or Starlight Park, this catalogue’s treatment of Coney Island alone makes sense as it deals with a singular institution that has become a keyword for a place of imagination, frenzy, and hope, as well as despair. The authors’ skillful examinations of popular culture alongside well-regarded works of fine art should be applauded. Indeed, students of both social history and American art history will be richly rewarded by this book, which is a valuable resource for anyone interested in American visual culture.

The exhibition associated with this catalogue was reviewed in Issue 1.2 by Adam M. Thomas. Click here to read the review.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1553

Notes

- This has been previously examined by other scholars, including Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “Topsy at the Dressing Table: Visual Apocrypha and Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Invited talk at the The Landscape of Slavery Conference, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, March 2008. ↵

About the Author(s): Christopher C. Oliver is Assistant Curator of American Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and a doctoral candidate in the History of Art and Architecture, University of Virginia.