The Critical Deployment of Amateurism in 1910s New York

At critical moments during the 1910s, the avant-garde in New York carefully employed amateur aesthetics to broaden the contours of art production and challenge traditional values of process and product. Not confined to a single group or school, the foundational advancements of American modernism were heavily predicated on and interlaced with a deliberately cultivated strain of amateurism. Far more nuanced than a simple rejection of high art or a retreat from modernism and theoretical expertise, amateurism was a path forward for American artists. Its fluid and boundless definition allowed artists to interpret the term at will and draw upon diverse sources from outside the canon while still engaging with avant-garde ideals of authenticity and intuition. The introduction of amateur art reframed contemporary theory with a Yankee sensibility and analytical straightforwardness that connected modernism with a local culture. Amateurism spoke to a homegrown, uncontaminated tradition that could be part of a usable past that was as distinctly American as it was aesthetically radical.

Demonstrating the range of amateurism as a tool of resistance and critique, this essay considers its advantages in three instances. We begin with the 1911–12 season at Alfred Stieglitz’s “291” gallery that featured the work of Gelett Burgess and art by local children. The gallery, while celebrating the untrained mark of amateur artists and distancing itself from its recent Symbolist past, realigned its exhibition program with Stieglitz’s journal Camera Work, which was then entering an era of radical iconoclasm. The influence of the visual components of amateur design, particularly the geometry of Shaker furniture and buildings, on Charles Sheeler and the burgeoning machine aesthetic within Walter and Louise Arensberg’s salon will also be considered. Florine Stettheimer’s deliberate rejection of the practices and expectations of fine art practices will also be explored as another instance of modernist amateurism. During the 1910s, amateur art was inflected with aesthetic and political radicalism and yet was also deeply American; at the same time, it challenged the genteel tradition of the nineteenth century and redefined a national spirit in the arts while remaining on the cutting edge of modern philosophy and an international avant-garde. By 1917, amateur art and amateur attitudes were considered culturally valuable and worthy of deliberate cultivation by the Society of Independent Artists, who not only encouraged amateurs to participate by eliminating a jury but specifically sought to include nontraditional media in their inaugural exhibition.1

The embrace of amateurism was part of a larger drive to develop a national aesthetic. The impoverished state of American art was a frequent lament in the early twentieth century, and cultural critics increasingly insisted that to foster growth, it was necessary to broaden the definitions and expectations of fine art. The 1909 essay by Van Wyck Brooks, “Wine of the Puritans,” argued that even if the current generation was not ready to produce an American art, it was vital to first recover some local tradition as a starting point. Setting the tone for the coming decade, he proclaimed: “Teach our pulses to beat with American ideas and ideals, absorb American life, until we are able to see that in all its vulgarities and distractions and boastings there lie the elements of a gigantic art.”2 The nature of this American spirit, its translation into the visual arts, and the navigation of cultural independence from Europe would dominate artistic discourse through the 1930s. The straightforward and homegrown qualities of vernacular culture, embodied in both the commercial/industrial aesthetic and amateurism, were local currents that could be celebrated as uniquely American. While superficially paradoxical, these two strains of production were united in their resistance to traditional high art—and both were central to the satirical work of Gelett Burgess (1866–1951), whose work was exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291 in November 1911.

Stieglitz’s Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (known as 291) hosted the first wave of modernism in New York. In his roles as gallerist and publisher of the journal Camera Work, Stieglitz (1864–1946) entertained multiple and often conflicting allegiances during this decade, but while the Symbolist tendencies of his circle have been established, scholarship has dismissed the inclusion of amateur art among his activities.3 In 1910, Stieglitz shifted his emphasis to the promotion of American modern art beyond photography and a new level of iconoclastic critique emerged among his circle.4 Differentiating Stieglitz’s circle of artists from both European and American academic traditions, amateurism was a potent force; its intrinsic rejection of academicism and high art was coupled with an attention to process and a privileging of intuition that could still incorporate contemporary modernist theories (specifically the writings of Henri Bergson and Wassily Kandinsky) while connecting to a native source of inspiration.5

Stieglitz often set the stage for the exhibitions at 291 within the pages of Camera Work; the writings of Bergson were given special prominence in the months around his first exhibitions of amateur art, supporting and legitimizing the shifting hierarchies. Published in the October 1911 issue of Camera Work, “An Extract from Bergson” (taken from Creative Evolution), specifically championed intuition over intellect, upending academic expectations and traditional elitism. Bergson argued that intellect dealt with only a view of reality while intuition entered into the very nature of life. To access the élan vital, the “intention of life, the simple movement that ruins through the lines, that binds them together and gives them significance,” it was necessary to look beyond rationality to empathetically reach the subject’s essence.6 While Bergson’s theories found a sympathetic home in the Stieglitz circle, prepared by Symbolist notions of equivalence and suggestion, the fuller implications of his iconoclasm and prioritization of intuition over intellect would ultimately displace the erudite and elitist decadence of the movement.

In January 1912, Stieglitz excerpted a passage from Bergson’s 1900 essay “Laughter,” which argues that the deepest understanding of nature would be achieved by experiencing the world with a “natural detachment, one innate in the structure of sense or consciousness, which at once reveals itself by a virginal manner.” This intuitive, not learned, knowledge would empower the artist to access the “native purity” of his subject. Bergson then directed such artists with a unique objective, writing, “art, whether it be painting or sculpture, poetry or music, has no other object than to brush aside accepted generality, in short, everything that veils reality from us, in order to bring us face to face with reality itself.”7 Furthermore, humor was an essential element of this progressive revolution, especially capable of overthrowing tired conventions. This same issue of Camera Work featured Burgess and his recent show at 291.

Indeed, it was in this intellectual atmosphere that Stieglitz exhibited the deliberately unskilled watercolors of Burgess in November 1911. His exhibition, Essays in Subjective Symbolism, was comprised of twenty-five paintings that lampooned the moody pretentions of nineteenth-century decadents.8 Burgess subverted the ineffable Symbolist subject with cartoonish simplicity and grandiose but absurd language, using titles such as Memory: An Attempt to Overtake a Part That Moves Heroic in Our Mind, Which Can Never Again Be Real (fig. 1). In both subject and style, his satirical series created new distance between Stieglitz and the ideals of Symbolist painting and photography.

The exhibition brochure, reprinted in Camera Work and extensively quoted in the New York Times (fig. 2), explained that “Mural painters, innumerable sculptors, stamp and seal designers and advertising men would seem to have squeezed all the juice out of graphic symbolism.”9 Burgess ironically announces his intention to return Symbolism to a more suggestive state; the work directly caricatures Symbolist painting, its hyperbolic tropes laid bare with unforgiving simplicity. His description completely deflates the type:

You are all well acquainted with Grandmother of Symbolism, good old Mrs. Industry, in her nightie and Greek helmet, surrounded by scrolls and globes, surveying the distant railroad train lighted by a setting sun. You know her good-looking nephew, Mr. Henry W. Workingman, in a neatly folded paper cap and clean overalls, holding his cog wheel in one hand and his hammer in the other, gazing proudly at a blue print.10

In the place of these clichés, Burgess creates a proxy of a cartoon icon, or a literal symbol, which he called a “liverbone.” The liverbone was not new in Burgess’s oeuvre, but was instead a subset of the “goop” characters that had previously appeared in his popular comics.11 Deliberate simplifications of human forms (fig. 3), goops acted on their worst impulses (although frequently in the context of teaching children about more proper behavior). They were central to Burgess’s commercial career as a humorist, appearing in popular magazines such as St. Nicholas and Harper’s Bazaar as well as a series of books.12 By incorporating his liverbone into this series of watercolors, Burgess teeters between the unskilled amateur painter and the highly successful commercial illustrator, two poles that each skirt the typical boundaries of the fine artist we associate with the Stieglitz Circle.

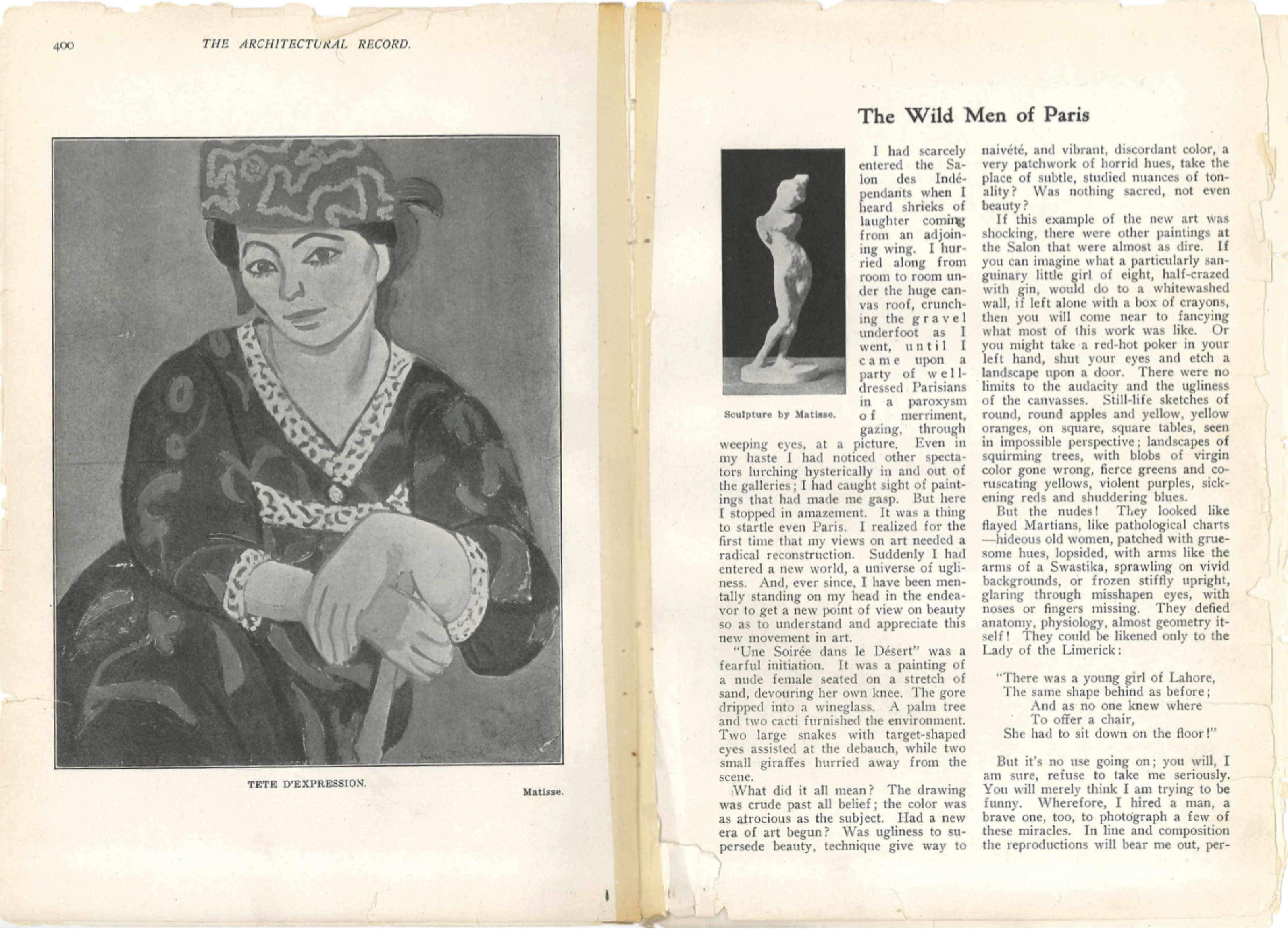

Burgess’s self-proclaimed artistic deficiency was central to his attitude; he clearly explained, “I do not think I can paint. I know I cannot.”13 Yet Burgess was no art world naïf. In addition to his work as a publisher of little magazines, his “The Wild Men of Paris: Matisse, Picasso, and Les Fauves” (fig. 4), was the first American review of the 1908 Salon des Indépendants. It provides an informed (if not entirely convinced) account of the European avant-garde.14 While humorous in parts, his essay dealt seriously with the formal and philosophical dimensions of modernism and featured interviews with Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, André Dérain, Pablo Picasso, and Jean Metzinger, as well as illustrations of their recent work.

Despite his uncertainties about the painterly innovations of the avant-garde, in the end of that review, Burgess defended the disruptions of Fauvism and Cubism as justifying

Nietzsche’s definition of an ascendant or renascent art. For it is the product of an overplus of life and energy, not the degeneracy of stagnant emotions. It is an attempt at expression, rather than satisfaction; it is alive and kicking, not a dead thing, frozen into convention. And, as such, it challenges the academicians to show a similar fervor, an equal vitality. It sets one thinking; and anything that does that surely has its place in civilization.15

Burgess presented his own series along these same philosophical lines, admitting to the New York Times, “They will of course be misinterpreted; they will be taken too seriously and too frivolously . . . but if the paintings stimulate anyone’s imagination they will have done their work.”16 Taken alongside his statements, the images undermine the authority of both academic standards and an older generation of the avant-garde, setting them up as ossified relics when compared to the fresh vitality and irreverence of Burgess’s gleeful amateurism.

The cartoonish nature of his paintings was key to the success of this balance. He positioned his work along the border between amateur and commercial art, explaining, “like the mediaeval artists who painted tavern signboards with real lions or black horses or Turks’ heads, for the benefit of those who could not read the lettered name, so I put the philosophy of aesthetics in familiar, natural graphic guise.”17 While he maintained his sincerity in the press, Burgess had previously published several volumes of humorous essays, several of which strike the pseudo-intellectual tone of his “Subjective Symbolism,” offering assurance that his intent is hardly serious.18

Compensating for his professed lack of skill, Burgess relied on conventions common to both commercial and amateur art. Not unlike the creation of a brand logo, he adopted the liverbone as an expedient means of expression and employed a cartoon style that avoided the techniques of academic execution. The result thoroughly confounded elements of the highbrow and lowbrow, caricaturing the elitist Symbolist movement. His iconoclasm suggests the intrinsically nonsensical nature of traditional painting while offering no viable path forward. During their exhibition at 291, Burgess’s goops took on an even higher level of potency, particularly when seen in the context of the dialogue between the gallery and Camera Work. This was a moment of growing iconoclasm, and Burgess’s liverbone distanced the Stieglitz Circle from its origins, opening a path for greater experimentation. The commonsense, seemingly straightforward approach of the amateur deflates the hyperbole of high art. Indeed, Burgess’s series of drawings was perhaps the first precedent within the Stieglitz Circle of a deliberate contamination of high art with lowbrow elements, one that has been overlooked in the scholarship in favor of the 1913 abstract caricatures of Marius de Zayas or the machine images of Francis Picabia.19

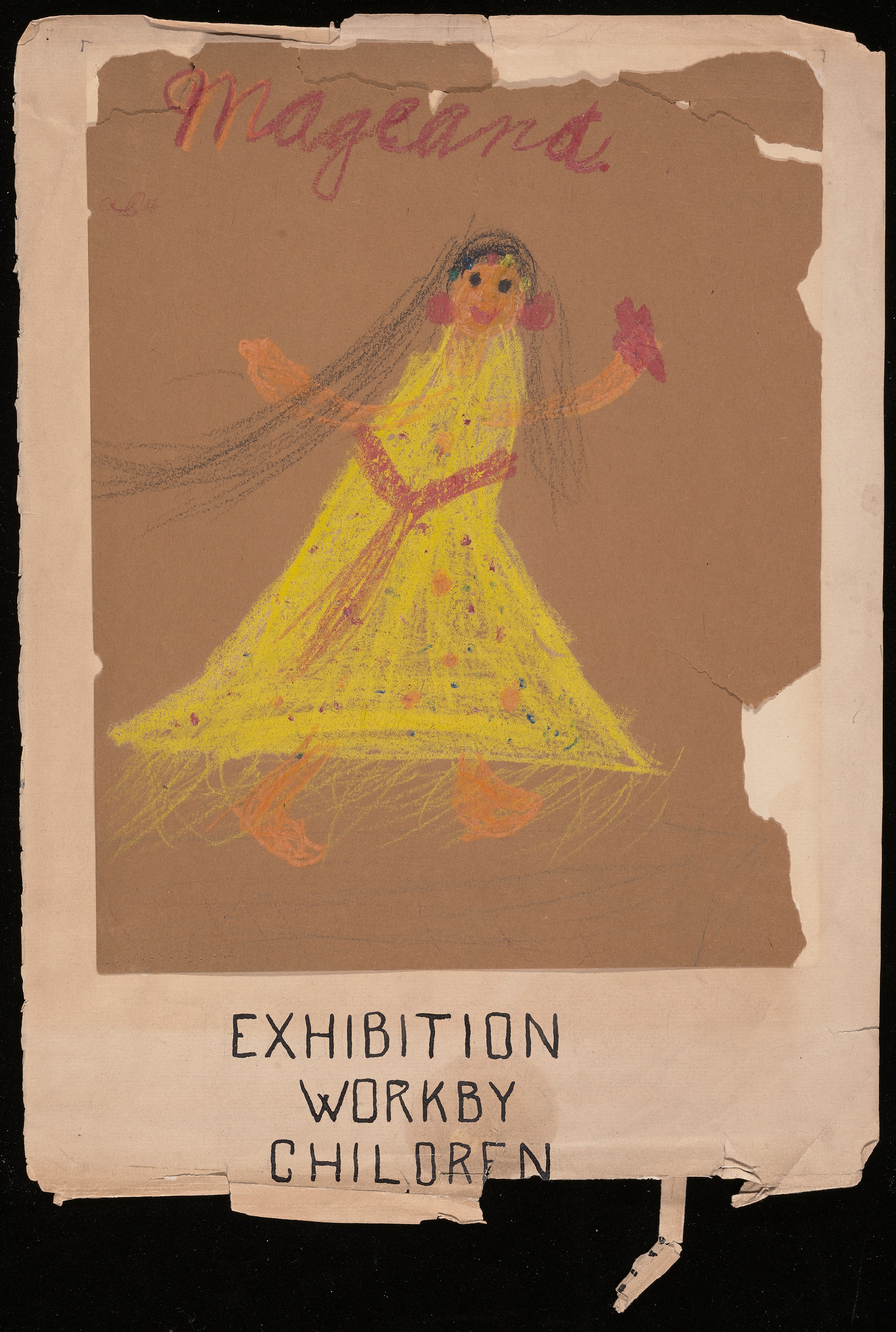

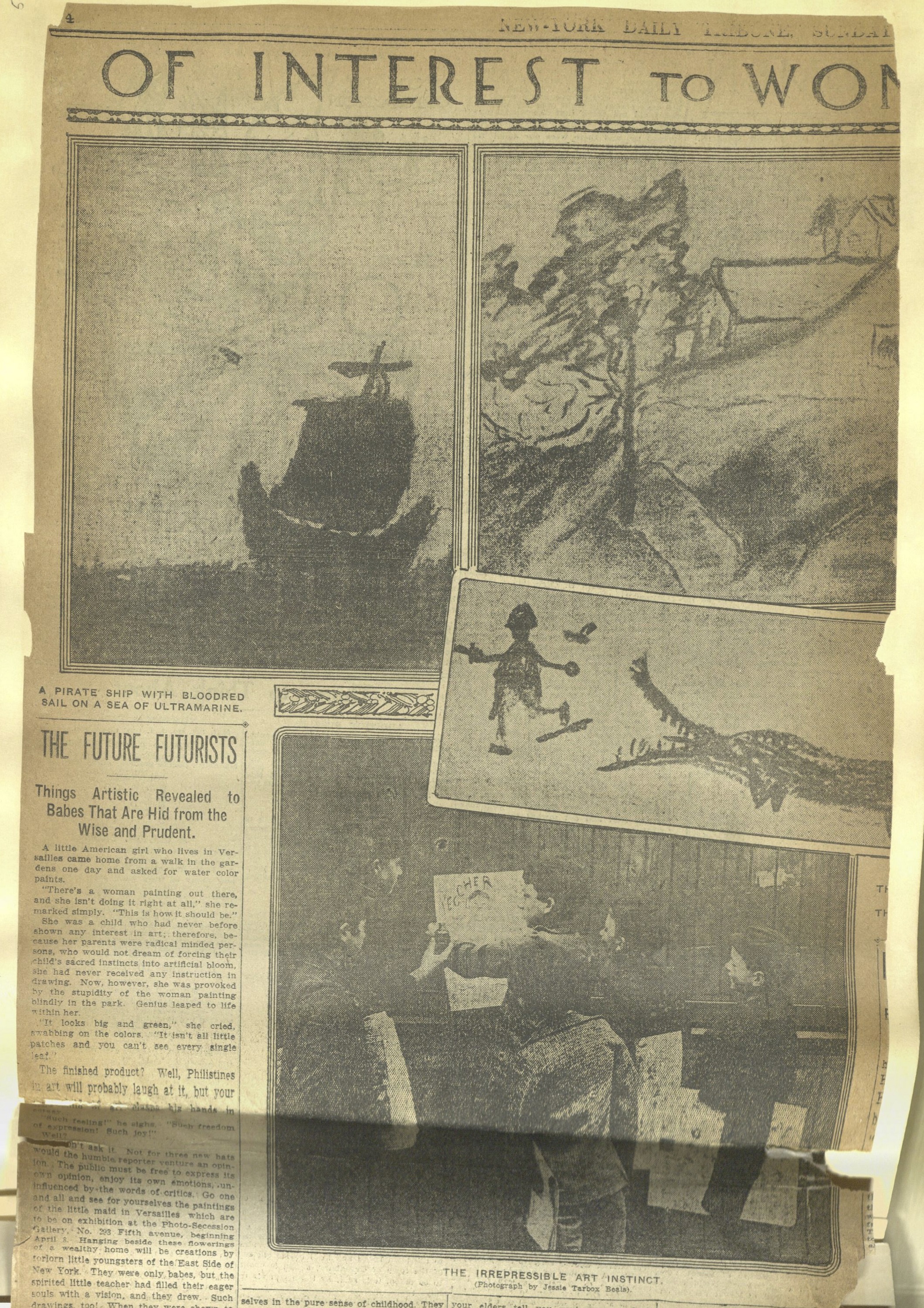

With children’s art, Stieglitz engaged directly with language and ideology that valued free and unfettered expression rather than academically trained conformity. In a rare interview, he advocated: “Give a child a brush and a paint box and leave him alone. Don’t bother him with theories, don’t attempt to confine his genius within established limits.” This sentiment closely echoed anarchist educational philosophies similar to those of the New York Ferrer Center and Modern School.23 The press quickly acknowledged this radicalism: the Sunday New York Daily Tribune declared them “The Future Futurists” (fig. 7), and Stieglitz’s interview with the New York Evening Sun characterized the show as “a reflection of the social unrest of the whole country.”24

The artistic implications were similarly revolutionary, challenging the supremacy of mature technical expertise and cultivated style. The first children’s exhibition was thoroughly documented in the July 1912 issue of Camera Work, forming a theme that connected several essays in that volume, including excerpts from Kandinsky’s newly published Über das Geistige in der Kunst (On the Spiritual in Art) and Marius de Zayas’s essay, “The Sun Has Set.”25 Among the artists of the Stieglitz Circle, the children’s amateur work reinforced the new hierarchies suggested by Bergsonian intuition and Kandinsky’s “inner necessity.”26 Although de Zayas did not categorize work by children as art, he explained that the children did express a innovative and spontaneous nature: “From this, we conclude that those who consciously imitate the work of children, produce childish work, but not the work of children. This confirms, too, the principle that ‘unconsciousness is the sign of creation, while consciousness at best that of manufacture.’”27

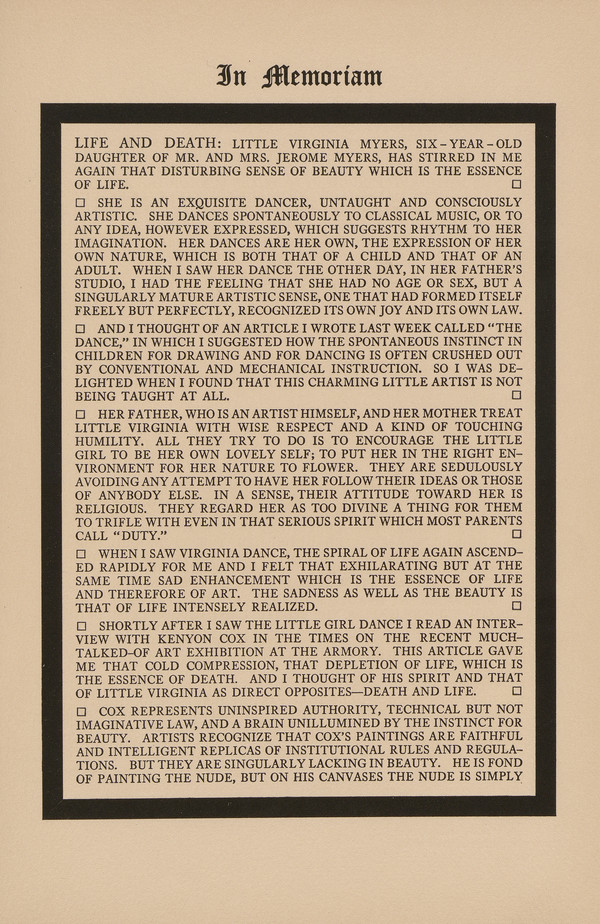

Also published in this issue was “In Memoriam” (fig. 8) by the anarchist Hutchins Hapgood, which offered a funereal notice for academicism. Printed with a thick black border typical of mourning cards, Hapgood described a young girl’s dancing as a “singularly mature artistic sense, one that had formed itself freely but perfectly, recognized its own joy and its own law,” a freedom cultivated by her parents, who “are sedulously avoiding any attempt to have her follow their ideas or those of anybody else.” 28This example is then contrasted with the work of Kenyon Cox, the acclaimed academic painter: “I thought of his spirit and that of little Virginia as direct opposites—death and life. Cox represents uninspired authority, technical but not imaginative law.”29 The amateur work of children became an exemplar of free expression, intuition, and iconoclasm, attributes central to the modernist reinvention of painting. Stieglitz hosted three additional exhibitions of children’s art before closing 291 in 1917, marking its continued importance to the development of American modern art.

Folk art represented another iteration of the amateur aesthetic that was celebrated in the 1910s; it provided an important precedent for an American vernacular style that could be folded into the conceptual and experimental salon of Walter and Louise Arensberg, embodying a native past and new Cubist aesthetics. Folk art allowed for an appreciation of inventive forms that ranged from Shaker asceticism to the whimsical and imaginative, but did not lead to a particular style. It countered the growing professionalism of the art world while simultaneously supporting Bergsonian upheaval and anti-academicism.

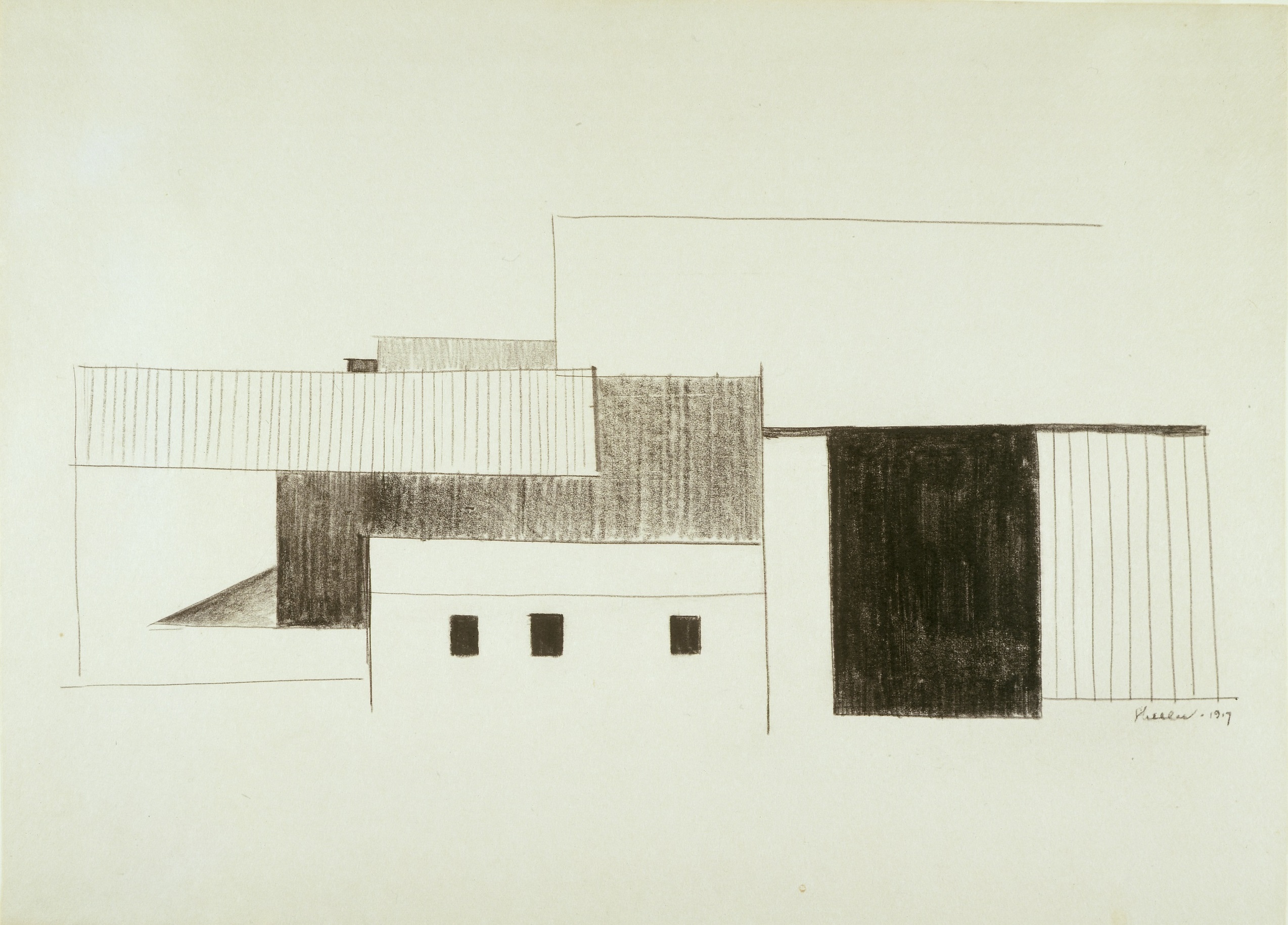

Guided by local needs and materials, Shaker design operated outside of highbrow traditions of design and was intrinsically American. Although these objects reflected a high level of skill, the broader public still viewed them as amateur crafts in the 1910s. Their later acclaim grew from a small circle of admirers that included Walter and Louise Arensberg, who collected and exhibited modern art along with “primitive” and vernacular objects (including Shaker furniture) that they believed to have aesthetic qualities that confirmed the authenticity of contemporary experimental art. Charles Sheeler (1883–1965) was among the artists who shared the couple’s appreciation for these pieces; their example was critical to his development of a machine imagery that was vernacular, had clean lines, and was supposedly authentically “American.” Demonstrating this mutual interest, the Arensbergs purchased Sheeler’s Barn Abstraction (fig. 9) and displayed it in their living room (fig. 10).

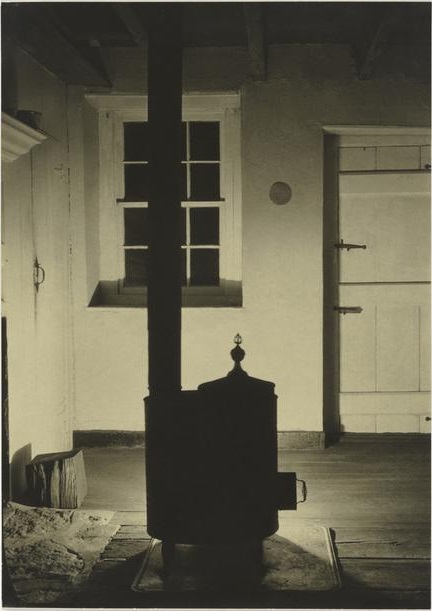

During the 1910s, Sheeler rented a cottage in Doylestown, located in rural Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Friends with the American material culture specialist and collector Henry Mercer, Sheeler was inspired to collect Shaker works, which he integrated into his photographs and paintings to create images grounded in both traditional structures and modern abstraction.30 This was an important turning point for his work. His Doylestown photographs (fig. 11)—and related works, including Barn Abstraction—featured “seemingly mundane features of the house, such as doors, windows, staircases, a cast-iron stove, and an empty mirror.”31 This signaled a change from his earlier landscapes, which had been painted to “communicate his sensations of some particular manifestation of cosmic order,” to a more grounded approach that foreshadowed elements of his machine aesthetic.32

The preindustrial forms of amateur craftsmen and builders provided a connection to an American past while offering visual forms contiguous to modernist aesthetics. The nature of these Shaker objects as functional objects would have further connected them to the machine forms then garnering appreciation among the Arensberg circle (perhaps most notably in the work of Sheeler’s close friend, Morton Schamberg). Sheeler’s attitude suggests that he was motivated largely by the straightforward use of materials and shape, explaining that he “sought neither the quaint [n]or the historical.” 33In the notes for his autobiography, he elaborated on this point, explaining:

Forms created for the best realization of their practical use may in turn claim attention of the artist who considers an efficient working of the parts toward the consummation of the whole of primary importance in the building of a picture. Evidence of this accomplishment aroused my interest in the early barns . . . in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Their shapes were determined by their practical use and by the combination of materials, wood, stone, plaster . . .34

While the contrasting facets of the barn can be understood in relation to Cubist collage and construction, they also emphasize the evident pragmatism of the structure. The coalescence of the object along both lines simultaneously reveals the appeal of skilled and intuitive forms for a modernist like Sheeler. Indeed, in 1938 Constance Rourke referred to these buildings as “urformen,” or “source forms,” which “were basic in American creative experience.”35

These subjects were not chosen innocently, but bridged Cubist abstraction and American material culture, producing work that could answer the call for a native aesthetic. While his paintings might appear straightforwardly realist, as a contemporary reviewer wrote, “we soon discover . . . that the realism is of a highly selected order, that choice, elimination, selection are the dominating factors in the design.”36 The pared-down aesthetics of the vernacular object converged with the aesthetics of modern art, particularly in the rejection of linear perspective in favor of multiple viewpoints and scalar irregularities. As Karen Lucic has noted, Sheeler’s barns were in opposition to Gilded Age architecture in their emphasis on “the nonacademic aspects of the structures—the rough handcrafted timbers, the irregular woodwork, the earthy material, the disregard for symmetry.”37 Barn Abstraction, with its sparse treatment of the lines and surfaces of the rural structure, transformed a traditional, thoroughly vernacular object into a modernist composition.

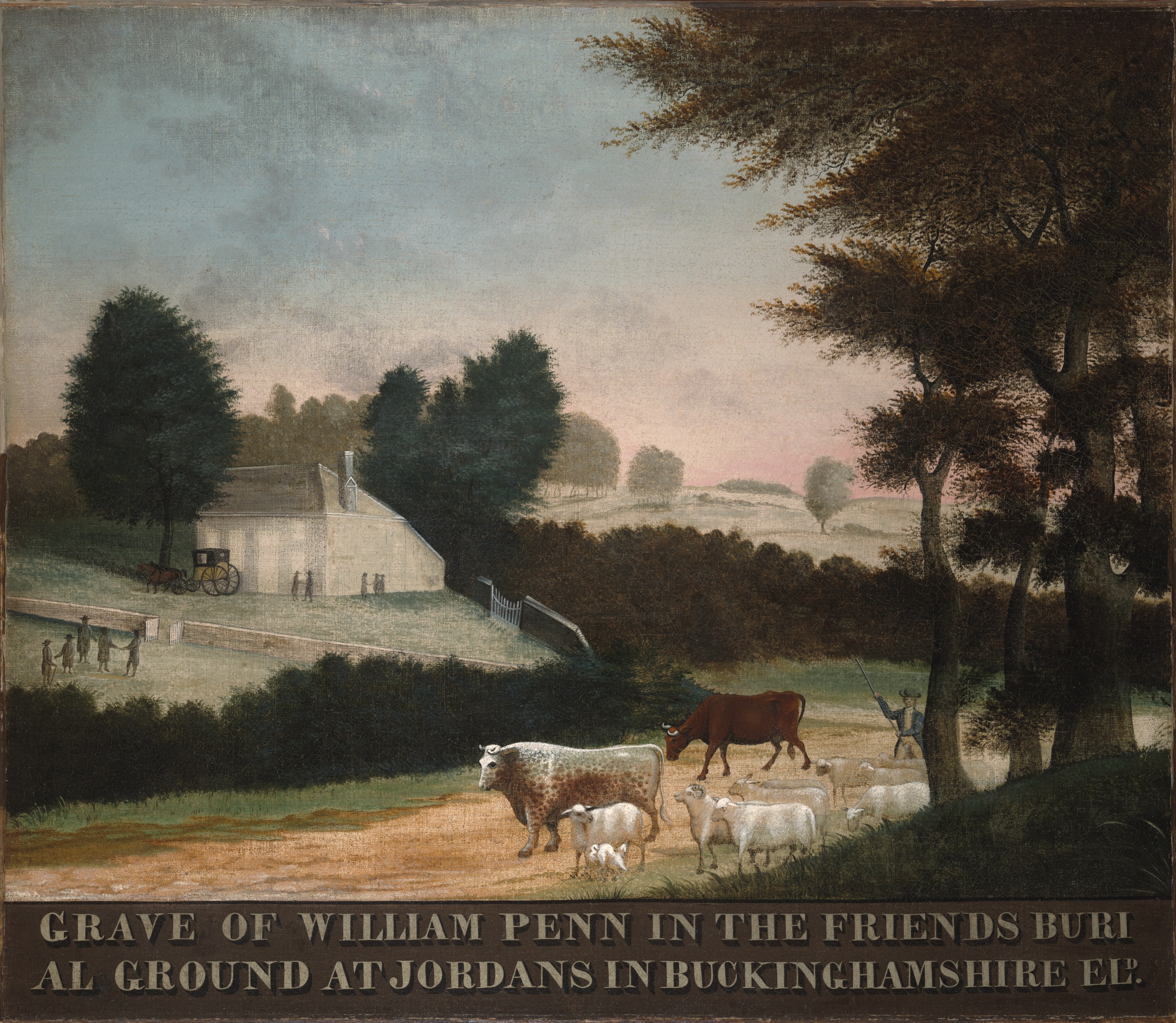

While some critics pointed to the influence of Cubism and modern abstraction on Sheeler’s images of barns, others have noted that these works bear strong resemblance to the paintings of folk artists such as Edward Hicks (fig. 12).38 Mercer collected Hicks’s paintings along with other examples of Bucks County folk art, and it is possible that he introduced Sheeler to the paintings.39

Certainly folk art was an important influence for Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944), contributing both to her idiosyncratic aesthetic and her carefully cultivated artistic persona. Although the result was stylistically opposite to that of Sheeler, they were similar in drawing from the example of amateur art as a way of processing and propagating modernist theory. Her use of seemingly naive techniques, such as continuous narrative (what Marcel Duchamp referred to as Stettheimer’s “multiplication virtuelle”), can be understood in connection to folk art but are simultaneously informed by Bergson’s writings on la durée.40 It was a deliberate strategy, undertaken with sophistication: hosting a popular salon with her sisters, Carrie and Ettie, Florine Stettheimer brought together a wide range of avant-garde artists, writers, and performers.41

Stettheimer’s Portrait of Andre Brook, Front View (fig. 13) and Portrait of Andre Brook, Back View (fig. 14) reveal her familiarity with folk art, particularly the tradition of painting pendant portraits of an estate. These two views of the family’s rented summer house in Tarrytown, New York, have much in common with amateur landscapes. The architectural details of the home are simplified into a softened geometry that repeats the patterned black windows and white façade without conforming to a grid. The structure itself is flattened into a façade, with no suggestion of depth. The impressionistic landscape also presents a shortened perspective, with little regard for scale. This is particularly evident in the front view of the house, which includes Florine, her mother, and her sisters clustered in the foreground. The bottom center of each canvas features an illusionistically painted label, reading “19-André-Brook-15,” an inclusion that amplifies the simple artificiality of the work.

Like Sheeler, Stettheimer adopted elements of the amateur to further her modernist inquiries, particularly her mingling of highbrow and lowbrow conventions.42 While her style appeared naive or untrained, Stettheimer had studied art in both America and Europe. Enrolled for a time at the Art Students League in New York, she worked with Kenyon Cox, who emphasized the old masters and believed that modern artists needed to extend, not eviscerate, these traditions.43 Stettheimer chose to place her work in opposition to this academy. During the mid-1910s, Stettheimer rejected the academic training of her youth for a loosely drawn, more idiosyncratic style that recognized the anti-academic to possess a certain artistic authenticity. She reported that while she had “lots and lots” of art training, she was “rather glad it didn’t” take.44 In general, she held an iconoclastic attitude toward high culture, writing:

Oh horrors!

I hate Beethoven

And I was brought up

To revere him

Adore him

Oh horrors

I hate Beethoven45

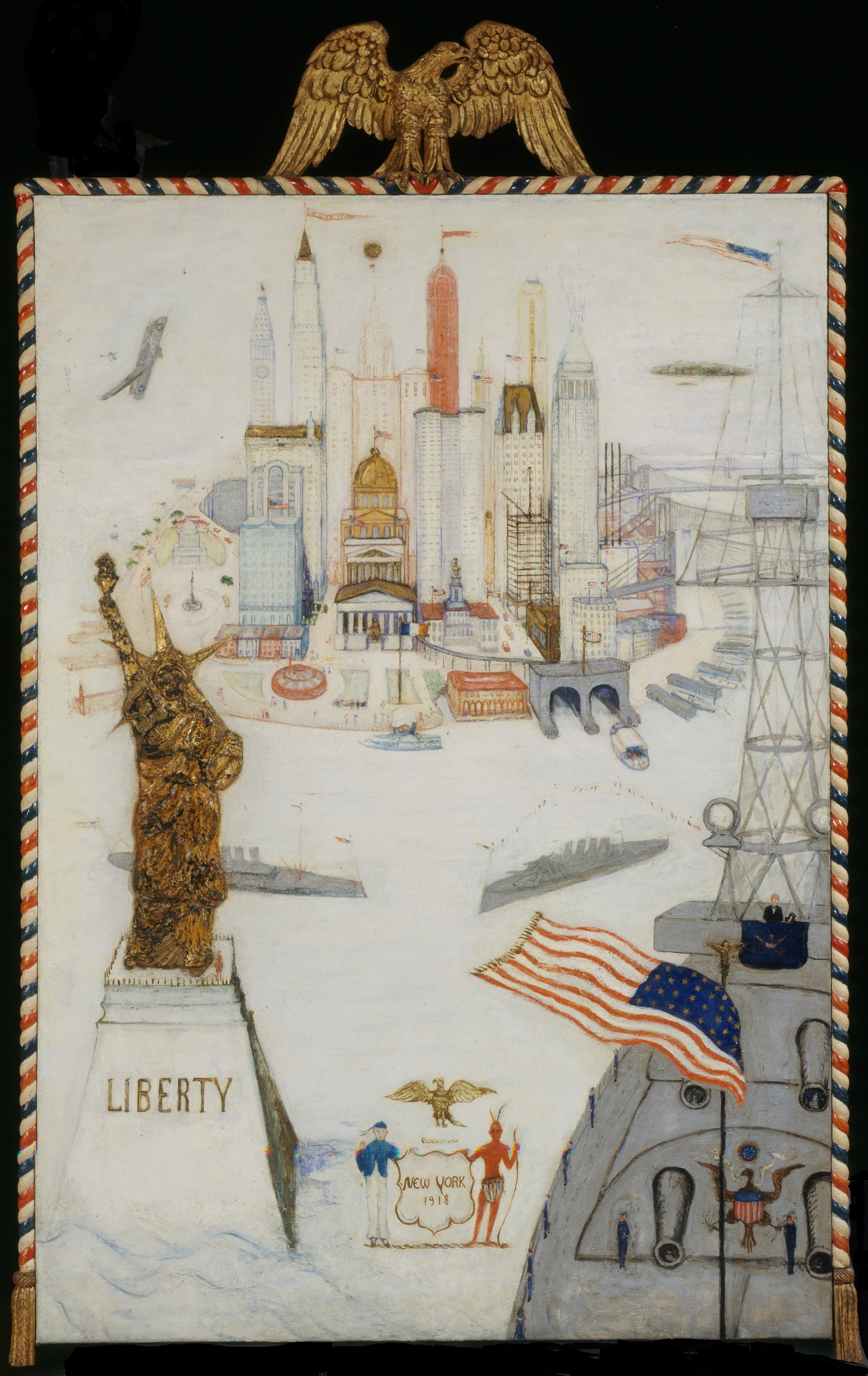

While her choices of subject were conventional, including portraits and flower paintings, Stettheimer’s deceptively autodidactic “cartoon” style subverted those conventions.46 This aesthetic was the result of deliberate, informed evolution and a sophisticated scrambling of codes that coexisted in high and low culture. In paintings such as New York (fig. 15), folk art simplicity, juxtapositions, and narrative detail are inflected with Bergson’s ideas about multiplicity and subjectivity. Merging her experience of sailing into New York harbor with the contemporaneous arrival of Woodrow Wilson (pictured at a lectern), Stettheimer created an image that was both highly specific and dream-like. Her city includes the modern Woolworth Building, the nineteenth-century US Customs House, and Grant’s Tomb, mixing architectural styles found throughout New York.47 The result compresses the actualities of time and space instead of accurately reproducing the city skyline. The work is not confined to a two-dimensional plane; it extends into space by means of the elaborate painted frame and gilded eagle, along with the three-dimensional relief of the Statue of Liberty in the foreground. This raised technique may have been another element inspired by folk art. It resembles a three-dimensional figurative technique used by Joseph Pickett (fig. 16), a contemporary Bucks County artist.48

Stettheimer’s work reveals how amateurism came to represent a new aesthetic attitude coded as genuinely American. Having rejected her more academic training to adopt an unskilled, idiosyncratic style, her faux-naive paintings demonstrate knowledge of folk art forms, an incorporation of Bergsonian theory, and a quiet but insistent professionalism. The model of the untrained artist provided an alternative professional identity for Stettheimer: an independent who identified as an artist without conforming to the dichotomy of academicism or modernism. Folk art offered a third option but also grounded her practice in a long-standing American tradition. Stettheimer’s style tested the conventions of highbrow art, especially academic form and finish, yet she did not label herself an amateur (although her amateur conceits were instrumental to her circumvention of developing modernist dogma). As Henry McBride observed, “Although she took all the license of a primitif she was by no means one herself.”49

Stettheimer’s adoption of folk art components demonstrate how amateur art was an unconventional but highly serviceable practice; it was relevant to modernist theories and had roots stretching back into America’s usable past. Holger Cahill would later describe folk art in terms that underscore its sympathies with modern art and Bergsonian intuition:

There is no doubt that these works have many technical deficiencies from the academic and naturalistic point of view, but with the artists who made them realism was a passion and not merely a technique. Surface realism meant nothing to them. It might be contended that this results from a lack of technical proficiency. The actual reason appears to be that folk artists tried to set down not so much what they saw as what they knew and what they felt. Their art mirrors the sense and the sentiment of a community, and is an authentic expression of American experience.50

In the coming decades, the influence of folk art on American modernism would continue to grow.51 By 1930, Marsden Hartley acknowledged the iconoclastic potential of folk art, recommending it to “anyone who is weary of the hocus-pocus of intellectualism in art, who seeks relief from the everlasting interrogation of the subject, who tires most of all of the greatest bore among the phrases of well-worn speech, namely, ‘What is Art?’”52

Cite this article: Sarah Archino, “The Critical Deployment of Amateurism in 1910s New York,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1686.

PDF: Archino, Critical Deployment

Notes

- The legal Certificate of Incorporation for the society began by stating that they intended to show “contemporary art, including paintings, sculpture, architecture, engravings, drawings, cartoons, water colors, pastels, miniatures, stained glass, enamel, porcelain, and faience.” Quoted in Clark S. Marlor, The Society of Independent Artists: The Exhibition Record, 1917–1944, (Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Press, 1984), 53. ↵

- Van Wyck Brooks, The Wine of the Puritans: A Study of Present-Day America (New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1909), 136. This essay prefigured Brooks’s larger condemnation of American culture found in his book America’s Coming-of-Age (New York: B. W. Huebsch, 1915); its traces can also be found in Robert Henri’s teaching philosophies; Robert Coady’s journal, The Soil (1916–1917); and a host of sympathetic cultural critics. ↵

- Those who have discussed Symbolist tendencies in the Stieglitz Circle include Sarah Greenough, Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2000); Kathleen Pyne, Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); and Kristina Wilson, “The Intimate Gallery and the ‘Equivalents’: Spirituality in the 1920s Work of Stieglitz,” Art Bulletin 85, no. 4 (December 2003): 746–68, among others. ↵

- William C. Agee named 1910 as a starting point of New York Dada for this reason in his “New York Dada, 1910–1930,” Art News Annual 34 (1968): 105–13. ↵

- Stieglitz published “An Extract from Bergson” in Camera Work 36 (October 1911): 20–21, and Bergson’s “What is the Object of Art?” in Camera Work 37 (January 1912): 22–25; Kandinsky appeared in “Extracts from The Spiritual in Art,” Camera Work 39 (July 1912): 34. ↵

- {Henri Bergson}, “An Extract from Bergson,” 20. ↵

- The excerpt included in Camera Work as “What is the Object of Art?” was taken from Bergson’s 1900 essay “Laughter,” originally published in Revue de Paris. The authorized English translation was issued in November 1911 as the book Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (New York: Macmillan Company, 1911). ↵

- A selection of Burgess’s writing has been collected in Alfred Jan, ed., The Gelett Burgess Sampler: Ethics and Aesthetics (Vancleave, MS: Surinam Turtle Press, 2012). ↵

- Gelett Burgess, “Essays in Subjective Symbolism,” reprinted in Camera Work 37 (January 1912): 46; and “Gelett Burgess Invents a New School of Art,” New York Times (November 26, 1911). ↵

- Burgess, “Essays in Subjective Symbolism,” 46. ↵

- See Gelett Burgess, “War-Song of the Liverbone Goops,” Harper’s Magazine 112 (April 1906): 810. ↵

- Burgess might be most famous today for his humorous quatrain, “Purple Cow”: “I never saw a Purple Cow, / I never hope to see one; / But I can tell you, anyhow, / I’d rather see than be one.” First published in his little magazine The Lark 1, no. 1 (May 1895), it was reprinted in A Nonsense Anthology, ed. Carolyn Wells (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915). ↵

- “Gelett Burgess Invents a New School of Art.” ↵

- Gelett Burgess, “The Wild Men of Paris: Matisse, Picasso, and Les Fauves,” Architectural Record 27, no. 5 (May 1910): 400–14. ↵

- Gelett Burgess, “The Wild Men of Paris,” 414. ↵

- “Gelett Burgess Invents a New School of Art.” ↵

- “Gelett Burgess Invents a New School of Art.” ↵

- Johanna Drucker sets an earlier precedent for this understanding of Burgess’s work in her examination of his 1896 project, Le Petit Journal des Refusées, which she argues was “a parody of the ways literary elitism is produced and received in print culture . . . {but} meant to be enjoyed by the very scene and circles whose activities and attitudes it exposes.” See Johanna Drucker, “Le Petit Journal des Refusées: A Graphical Reading,” Victorian Poetry 48, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 138. ↵

- For more on these exhibitions, see Greenough, Modern Art and America; Douglas Hyland, Marius de Zayas: Conjuror of Souls (Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1981); Willard Bohn, “The Abstract Vision of Marius de Zayas,” Art Bulletin 62, no. 3 (September 1980): 434–52; and Willard Bohn, “Picabia’s ‘Mechanical Expression’ and the Demise of the Object,” Art Bulletin 67 (December 1985): 673–77. ↵

- These exhibitions of children’s art were an important component of Stieglitz’s attack on tradition. It was a sustained volley: from 1912 to 1916, Stieglitz hosted four exhibitions of work by children. He also planned an issue of his journal, Camera Work, dedicated to “Children’s Work, in picture and in words,” but that was never published. {Alfred Stieglitz}, “Numbers of Camera Work in Preparation,” in Camera Work 46 (1914): 52. The children and art number was meant to be a collaboration with Dr. A. A. Brill, the translator of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, among other works. The two men met at one of Mabel Dodge Luhan’s salons, and although the issue was never realized, the plans point to the centrality of this idea to Stieglitz during this period. See Debra Bricker Balken, Debating American Modernism: Stieglitz, Duchamp, and the New York Avant-Garde (New York: American Federation of Arts in association with D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2003), 56. In addition to exhibitions of children’s art, Stieglitz also published a poem by Mary Steichen “age not quite nine” in Camera Work 42/43 (April/May 1913): 14. ↵

- Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, eds., Der Blaue Reiter Almanach (1914; New York: Da Capo, 1974). The almanac was originally published in German in 1912. ↵

- Stieglitz quoted in “Some Remarkable Work by Very Young Artists,” reprinted in Dorothy Norman, Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer (New York: Random House, 1973), 115. ↵

- Stieglitz quoted in “Some Remarkable Work by Very Young Artists.” Stieglitz’s collaborator on these exhibitions, Abraham Walkowitz, was a Ferrer Center regular. ↵

- “The Future Futurists—Things Artistic Revealed to Babies That are Hid from the Wise and Prudent,” in Sunday New York Daily Tribune, undated clipping, Stieglitz scrapbook, Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven; and Stieglitz; “Some Remarkable Work by Very Young Artists.” ↵

- {Wassily} Kandinsky, “Extracts from ‘The Spiritual in Art,’” Camera Work 39 (July 1912): 34. The text was sent to Stieglitz by Marsden Hartley and most likely translated into English by Stieglitz himself, as a published translation did not appear until 1914. Marius de Zayas’s “The Sun Has Set,” Camera Work 39 (July 1912): 17–21, is commonly seen as a proto-Dada statement, opening with the dramatic claim: “Art is Dead.” ↵

- Marsden Hartley would directly link Bergson and Kandinsky in a December 1912 letter to Stieglitz, explaining, “I am convinced of the Bergson argument in philosophy. That the intuition is the only vehicle for art expression and it is in this basis that I am proceeding. My first impulses came from the mere suggestion of Kandinsky’s book.” Marsden Hartley to Alfred Stieglitz, letter received December 20, 1912, O’Keeffe/Stieglitz Archive. As Stieglitz and Hartley were both reading from the original German edition, the term innere would have been more closely aligned with Bergsonian concepts of the élan vital than a merely subjective expressive. This distinction is discussed by Rose-Carol Washton Long in German Expressionism: Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National Socialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 38–39. ↵

- De Zayas, “The Sun Has Set,” 20–21. ↵

- Hutchins Hapgood, “In Memoriam,” Camera Work 39 (July 1912): 51–52. ↵

- Hapgood, “In Memoriam,” 51. ↵

- Karen Davies {Lucic}, “Charles Sheeler and the Image of Rural Architecture,” Arts 59 (March 1985): 135–39. ↵

- Karen Lucic, Charles Sheeler in Doylestown: American Modernism and the Pennsylvania Tradition, exh. cat. (Allentown, PA: Allentown Art Museum, 1997), 20. ↵

- Charles Sheeler in The Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters, exh. cat. (New York: M. Kennerley, 1916), 70, as quoted in Carol Troyen and Erica Hirshler, Charles Sheeler: Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1987), 64. ↵

- Charles Sheeler, quoted in Frederick S. Wight, “Charles Sheeler,” in Charles Sheeler: A Retrospective Tradition, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Art Galleries, University of California, 1954), 27. Davies {Lucic} complicates this influence in “Charles Sheeler and the Image of Rural Architecture,” demonstrating Sheeler’s appreciation of early American craft and its history. ↵

- Charles Sheeler, “Autobiographical Notes,” Charles Sheeler Papers, Archives of American Art. ↵

- Constance Rourke, Charles Sheeler: Artist in the American Tradition (New York: Harcourt, 1938), 69. ↵

- Forbes Watson, “Charles Sheeler,” Arts 3 (May 1923): 335–44. ↵

- Lucic, Charles Sheeler in Doylestown, 65. ↵

- Henry Sayre, “American Vernacular: Objectivism, Precisionism, and the Aesthetic of the Machine,” Twentieth Century Literature 35, no. 3 (Autumn 1989): 310–42, discusses the similarities between Sheeler’s Bucks County Barn and Hicks’s Cornell Farm at length. ↵

- Lucic, Charles Sheeler in Doylestown, 66. ↵

- Marcel Duchamp, letter to the Stettheimer sisters, May 3, 1919, as quoted in Elizabeth Sussman, “Florine Stettheimer: A 1990s Perspective,” in Elisabeth Sussman and Barbara Bloemink, Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1995), 49. Bloemink’s essay in that volume, “Visualizing Sight: Florine Stettheimer and Temporal Modernism,” also addresses Bergson as an important influence on Stettheimer, as many of her paintings concerned memories and nonlinear narration. ↵

- Florine Stettheimer intersected with both the Stieglitz and Arensberg circles; as frequent guests, both Duchamp and Stieglitz were portrait subjects for Stettheimer during the 1920s. For more information on the influential Stettheimer salon, see Emily Braun, “The Salons of Modernism,” in Jewish Women and Their Salons: The Power of Conversation, eds. Emily Braun and Emily Bilski (New York: Jewish Museum, 2005). ↵

- Barbara Bloemink expands on this idea, citing the links between Stettheimer’s famous Cathedrals series and Italian Renaissance painting in “Visualizing Sight” in Sussman and Bloemink, Florine Stettheimer, 89–92. ↵

- Barbara Bloemink, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 16–17. ↵

- Dorothy Dayton, “Before Designing Stage Settings She Painted Composer’s Portrait,” New York Sun (March 24, 1934), as quoted in Bloemink, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer, 243. ↵

- Florine Stettheimer, Crystal Flowers (Pawlett, VT: Banyan Press, 1949), n.p. ↵

- Sussman, “Florine Stettheimer,” 48. ↵

- Barbara Bloemink identifies the buildings depicted in “Visualizing Sight,” 72–73. ↵

- As recounted in Holger Cahill, American Folk Art: Art of the Common Man in America, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1932), 16, 33, Pickett was encouraged by an unnamed artist working at the New Hope colony to submit his work to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts annual exhibition in 1918. Although ultimately not included, his submission received three positive votes from William Lathrop, Robert Henri, and Robert Spencer. ↵

- Henry McBride, Florine Stettheimer, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946), 13. ↵

- Cahill, American Folk Art, 28. ↵

- The Whitney Studio Club held one of the first exhibitions of folk art in 1924. Holger Cahill’s exhibitions American Primitives (1930) and American Folk Sculpture (1931) at the Newark Museum predated his comprehensive 1932 show, American Sources of Modern Art, American Folk Art: Art of the Common Man in America at the Museum of Modern Art. Cahill also established the American Folk Art Gallery with Edith Halpert, who would later heavily promote folk art in relation to American modernism in her Downtown Gallery. ↵

- Marsden Hartley, “American Primitives,” in On Art, ed. Gail R. Scott (New York: Horizon Press, 1982), 186. ↵

About the Author(s): Sarah Archino is Assistant Professor of Art History at Furman University