The Decolonization of John Sloan

In recent years, historians have engaged decolonial research methods and pedagogical approaches that aim to dismantle the hegemonic structures of power that dominated the construction of academic knowledge from the beginnings of European conquest in the Americas.1 Early scholarship that asserted American exceptionalism and colonialist hegemony still forms the center around which the canon of American art has expanded since the 1970s. Today, it is critical that we return to primary sources to question the veracity of these foundational texts and the narratives that they provided for the story of American art. If colonial America and Americanist art-historical coloniality are to finally meet their end, we must also engage the challenging and purposefully obfuscated materials in the archive. We must ask ourselves why our scholarly predecessors may have chosen to craft intentionally deceptive accounts and how, in the present moment, we might act purposefully to supplant these accounts with more factual histories.

For example, due to the efforts of colonialist art historians, the illustrator and painter John French Sloan (1871–1951) has long been enshrined as a central figure within American art history. A member of “The Eight,” Sloan’s mature work was part of the so-called Ashcan School, dedicated to picturing working-class and immigrant European communities of New York City between 1900 and World War I. Although scholars have focused on numerous aspects of Sloan’s life and career, they have largely ignored the profound effects that his deeply held and remarkably clear colonialist beliefs of white racial superiority had upon his artistic production and teaching.2

The process of whitewashing Sloan began a little over a decade after his death when his early diaries were published under the title John Sloan’s New York Scene: From the Diaries, Notes, and Correspondence, 1906–1913. The book’s editor, Bruce St. John, then director of the Delaware Art Museum (DAM), purposefully omitted twelve of the thirteen times Sloan used the N-word in his diary.3 In this key text, which has been used countless times by generations of art historians working on Ashcan, the slur only appears once, as the title for the portrait of Eva Green by Robert Henri.4 St. John’s expunging of the term obscured Sloan’s white supremacist beliefs and was an act of colonialist art history that initiated a half-century of art-historical ignorance, radically skewing the history of American art.5

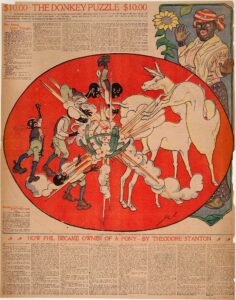

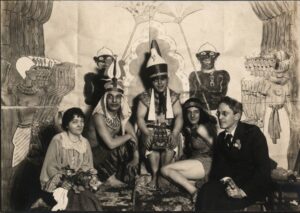

The John Sloan Manuscript Collection at the Delaware Art Museum, which was acquired by St. John from Sloan’s widow, Helen Farr Sloan, includes more than three hundred boxes of photographs, illustrations, and letters that provide considerable evidence of the artist’s racism.6 In the 1906 to 1913 diaries, Sloan exults in his own perceived white supremacy, making frequent use of the N-word to describe both strangers and African Americans whom he personally knew, including artist Henry Ossawa Tanner.7 Numerous illustrations in the collection, such as a puzzle of a mammy figure watching a group of Black children being kicked by a donkey from August 5, 1900, published in the Philadelphia Press (fig. 1), demonstrate Sloan’s use of vile racist stereotypes in his early visual art. The archive also contains photographs of the artist; his first wife, Dolly Sloan; colleague Everett Shinn; his classmates at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA); and his associates at the Art Students League in New York City engaging in numerous acts of derisive racial masquerade (figs. 2–4). A good party for these American modernists meant donning blackface, staging Orientalist masquerades, and painting grotesquely subjugated Black bodies onto theatrical backdrops. When considered in concert, these materials clearly show that Sloan would not only have been considered a racist by today’s standards but by those of his own era as well.

To continue to ignore the colonialist world view that saturated Sloan’s early career—to ascribe his repellent attitudes and behavior as typical of “a man of his time”—fails to account for the ways that racism impacted Sloan’s painting, which included almost no representations of Black subjects despite his living and working in neighborhoods with sizeable Black populations. Further, his attitudes helped to institutionalize racism in two of the most prominent American art schools in the early-1900s, affecting both his colleagues—including Shinn and Henri—and impacting younger artists who studied with him at PAFA and the Art Students League.8 Due to the intervention by St. John and choices made by subsequent scholars for whom issues of race have not been “a part of the project,” historical scholarship on Sloan was long silent on this issue. Thankfully, Alexis L. Boylan, Margarita Karasoulas, Lee Ann Custer, and other formidable scholars of the current century are beginning to elucidate Sloan’s racism and his relationship to whiteness by considering problematic representations of the non–Anglo Saxon populations that he both pictured and purposefully ignored in his art.9

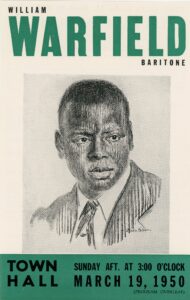

Interestingly, diary entries from the last seven years of Sloan’s life reveal that by middle age the artist had developed a different attitude entirely.10 When he resumed keeping diaries after a forty-year hiatus from the practice, Sloan wrote with reverence about the accolades garnered by Paul Robeson, the power of Richard Wright’s prose, and joy on finding himself seated next to W. E. B. Du Bois at a dinner held at the famed Knickerbocker Club.11 He also journaled about his antiracist conversations with white bigots.12 His art changed as well. Two years before his death in 1952, Sloan made a sketch of the African American baritone William Warfield for the opera singer’s debut at New York’s Town Hall (fig. 5). In the portrait, Warfield wears a suit coat and tie, his gaze intently focused on the future, his personhood fully visualized. Stylistically, it communicates more of an Eakins-like interiority than an Ashcan urbanism. It is also fifty years and a million miles removed from the racist caricatures of the donkey puzzle. Sloan got “woke” before he died.

It was the enlightened Sloan that St. John sought to preserve with his act of art-historical editing a decade later in the mid-1960s. St. John’s motivation to whitewash Sloan’s past may have been propelled by the impact of the Civil Rights Movement and efforts to desegregate downtown Wilmington, just a few miles from DAM.13 Three years after the publication of John Sloan’s New York Scene, uprisings that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., led the governor to call the National Guard to Wilmington, where they remained for nine months, the longest occupation of a US city since the end of the Civil War. As the director of a key cultural institution, St. John may have been rightly concerned about promoting an artist with profoundly racist beginnings to a community that was mired in racial inequality. His predicament and the choices that he made about how to deal with it should give us all pause to consider how our own research and writing choices may either prolong or help to bring about an end to colonial America.

Cite this article: Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “The Decolonization of John Sloan,” in “When and Where Does Colonial America End?” Colloquim, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12714.

PDF: Shaw, The Decolonization of John Sloan

Notes

- For a discussion of the ongoing nature of the colonial project, see Aníbal Quijano and Michael Ennis, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America,” Nepantla: Views from South 1, no. 3 (2000): 533–80, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/23906. ↵

- I want to thank Jordana Moore Saggese, Margarita Karasoulas, Lee Ann Custer, and Heather Campbell Coyle, who took time to discuss the problem of John Sloan’s racism and read versions of this essay. ↵

- John Sloan, John Sloan’s New York Scene: From the Diaries, Notes, and Correspondence, 1906–1913, ed. Bruce St. John (New York: Harper and Row, 1965). For the complete diaries, see the transcription “John Sloan Diaries, 1906 through 1913,” John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum, accessed May 25, 2021, https://delart.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/John-Sloan-Diaries-1906-to-1913.pdf. Examples of Sloan’s use of the slur appear in the entry for November 27, 1906, describing the streets near his home in Manhattan: “In the afternoon out, walked down 7th Avenue. Saw a poor, young drunken woman who was evidently the property of a n****r. He was shoving and dragging her along, speaking fiercely to her. {A} n****r neighborhood, saloons of the lowest sort” (125). Other diary entries reveal Sloan’s voyeuristic othering of Blackness, as he projects his own abjection onto his African American neighbors. On March 28, 1908, peeping out of the window of his apartment in the Tenderloin, a neighborhood with a large Black population, Sloan observed “a “n****r dressing in a little dirty, dingy hall room across back of us. The dingy white of the clothing and bed, etc. and the n****r invisible in the gloom, mixing in color with the dark” (332–33). The following year he made notes about his visit to the annual PAFA exhibition, on March 2, 1909, and he used the slur to denigrate artist and fellow academy alum Henry Ossawa Tanner, calling him “the n****r artist {who} has a big greasy looking canvas about the size of a large barn door {in an exhibition}” (493). And, the day after prize fight on July 4, 1910, in which Black boxer Jack Johnson soundly defeated Jim Jeffries, whom novelist Jack London had dubbed the “Great White Hope,” Sloan fell back on racism to recruit a fellow white man whom he met on the street in New York to his political beliefs: “Met a stranger on the street near Madison Square. Talked from prize fight n****r hatred to Socialism and he gave me his name. . . . He seems good material for Socialism” (727–28). ↵

- Sloan refers to this painting as both “N****r Gal” and then “Eva Green” in parentheses. Sloan, John Sloan’s New York Scene, ed. Bruce St. John (New York: Routledge, 2017), e-book. See also “John Sloan Diaries: Originals in the John Sloan Manuscript Collection Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum,” 653, https://delart.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/John-Sloan-Diaries-1906-to-1913.pdf. Eva Green is now in the collection of the Wichita Art Museum, https://wichitaartmuseum.org/our-collection/collection/eva-green. ↵

- My interest in the purposeful expurgation of evidence of slavery and anti-Black racism from the history of art began in graduate school when I first learned that the archive of the artist Charles Willson Peale had no records relating to an African-descended family that he enslaved in the period before gradual emancipation began in Pennsylvania. Scholars working with the collection, including the late Roger Stein, with whom I was then studying, agreed that Peale had purposefully destroyed these records to help burnish his legacy. My interest in the topic was renewed when I served as the third reader for Lee Ann Custer’s dissertation (cited in n. 9 below), but my engagement with Sloan was first prompted by my longtime friendship with art historian Joyce K. Schiller, who curated John Sloan’s New York (2007) at the Delaware Art Museum. Schiller was a remarkable scholar who looked closely at both objects and words. “Early on in my time here, Joyce and I started circulating the full diary transcripts to the writers for John Sloan’s New York, and then we began giving them to any interested researchers,” Schiller’s colleague and successor Heather Campbell Coyle wrote me. “When Joyce sent the PDF to scholars, she always underlined the point that John Sloan’s New York Scene was an edited or abridged volume. That book was how most scholars (myself included) first encountered his voice, and the most offensive passages referencing race were edited out. (I recently cross-referenced it.) Now, I think she was nudging us to read those digitized diaries with care and not just use them as searchable files to answer questions and build timelines.” Heather Campbell Coyle, Chief Curator and Curator of American Art, Delaware Art Museum, to author, June 15, 2021. ↵

- The John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Delaware Art Museum, accessed May 25, 2021, https://delart.org/researchers/digital-archives/john-sloan-manuscript-collection. ↵

- See n. 3. ↵

- The racism that was present in American art schools during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is a topic that deserves further research. One story that is often mentioned by art historians is how young Henry Ossawa Tanner was dragged from the studios at PAFA by his classmates, “crucified” with rope on an easel, and left in the middle of North Broad Street in downtown Philadelphia. At the center of this story is Tanner’s humiliation and how it helped motivate him to eventually expatriate to France where he spent most of his career. What is always absent from scholarly retellings of this story is anything having to do with the white students who acted so horribly to Tanner. What punishment did they receive? Were they expelled? Were they celebrated? Who were they? Joseph Pennell is the origin point for the story and was himself deeply racist and anti-Semitic while affiliated with PAFA and the Philadelphia Sketch Club. In The Adventures of an Illustrator, Pennell writes: “One night we were walking down Broad Street, he {Tanner} with us, when from a crowd of people of his color who were walking up the street came a greeting: ‘Hullo, George Washington, howse yer gettin’ on wid yer white fren’s?’ Then he began to assert himself and, to cut a long story short, one night his easel was carried out into the middle of Broad Street and, though not painfully crucified, he was firmly tied to it and left there. And this is my only experience of my colored brothers in a white school, but it was enough. Curiously, there never has been a great Negro or a great Jew artist in the history of the world” (The Adventures of an Illustrator, Mostly in Following His Authors in America and Europe {Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1925}, 54). ↵

- Alexis L. Boylan, Ashcan Art, Whiteness, and the Unspectacular Man (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017); Margarita Karasoulas, “Mapping Immigrant New York: Race and Place in Ashcan Visual Culture” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2020); Lee Ann Custer, “Urban ‘Voids’: Picturing Light, Air, and Open Space in New York, 1890–1935” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2021). ↵

- “John Sloan Diaries.” ↵

- See numerous entries in “John Sloan Diaries.” For example, on May 19, 1944, Sloan praises the awarding of an arts medal to “the great negro actor” Paul Robeson (37), and on December 23, 1945, he shares that he has “just been reading ‘Black Boy’ a beautiful self study by a negro writer Richard Wright” (238). On February 19, 1946, he writes of helping to sponsor an art exhibition connected to Negro History Week (275), and January 16, 1949, found him reading “a biography of John Hope {Franklin} a great man in the Negro movement” (916). Five days later, he was “pleased to find my seat at table next to Dr W.E.B. DuBois the distinguished negro” at an awards dinner held in the ultimate site of patrician white power, New York City’s Knickerbocker Club (919). ↵

- “I had a bit of a row with Mrs Williams who is a Southerner—negro question!!” (“John Sloan Diaries,” 1079. ↵

- The history of anti-Black racism in Delaware is complicated and does not need to be rehearsed here, but it formed the climate in which St. John was working. Although Delaware remained with the Union in the Civil War, it was a slave state until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Wilmington, its largest city, experienced significant anti-Black terrorism for the next hundred years, including a massive race riot during the “Red Summer” of 1919. Segregation was so much a part of the culture in Delaware that the public school system was not officially desegregated until 1964, ten years after the Brown vs. Board of Education, when the last “Negro schools” were closed. By that time, the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing in the “First State” and sit-ins and picketing were common in Wilmington. (As a part of trumpeting his credibility as a Civil Rights activist, President Joseph Biden has long pointed to stories of his participation in the 1962 and 1963 protests to integrate the Rialto Theatre in Wilmington. Such narratives likely are shared in order to serve as a counterweight to his more prominent anti-busing stance in the early 1970s.) In 1972, Delaware became the last state to remove public whipping, which was more often meted out as a common punishment to Black offenders than whites, from its criminal code. In June of 2020, following the national reckoning with symbols of white supremacy throughout the country, the state’s last public whipping post was finally removed from a square in Georgetown. ↵

About the Author(s): Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw is Class of 1940 Bicentennial Term Associate Professor in the Department of History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania