Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist

PDF: Pollock, review of Elizabeth Catlett

Curated by: Mary Lee Corlett and Rashieda Witter, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Carla Forbes and Catherine Morris, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum; and Dalila Scruggs, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Exhibition schedule: Brooklyn Museum of Art, September 13, 2024–January 19, 2025; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, March 9–July 6, 2025; Art Institute of Chicago, August 30, 2025–January 4, 2026

Exhibition catalogue: Dalila Scruggs, ed. Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies. Exh. cat. University of Chicago Press in association with the National Gallery of Art and Brooklyn Museum, 2024. 304 pp.; 240 color illus. Cloth: $65.00 (ISBN: 9780226836577)

A mere two miles from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the historic Barnett-Aden Gallery—one of the first art galleries in the United States dedicated to exhibiting Black artists—opened Elizabeth Catlett’s (1915–2012) first solo show in December 1947. Coming full circle on the occasion of the updated retrospective Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist, the National Gallery displayed the brochure that accompanied the Barnett-Aden show in its first interior gallery. Visible was Gwendolyn Bennett’s prescient foreword heralding Catlett as “a Negro woman whose interest in other women and other peoples will deepen and grow as her work develops and matures.”1 The exhibition proves Bennett’s early words indisputable, showcasing the strength of Catlett’s unwavering vision, talent, and ideals over seven decades of her artistic production.

Symbolically and physically situated outside of the interior gallery spaces and visible from multiple angles across the expansive East Wing atrium, the first installation—representing Catlett’s public art—served both as a thematic opening and chronological endpoint of the show. This framing reminds us that Catlett’s ultimate goal was never simply to earn acclaim from the art establishment, to fetch the highest price, to have her work privately collected, or to have it exhibited behind closed doors; indeed, she recognized with piercing insight the “class character, racist characteristics, and commercial base” of the art world.2 Her intention, in contrast, was emphatically clear: “Art needs to be public to reach the majority of Blacks.”3

![Museum interior showing three abstracted figural sculptures on pedestals. On a wall behind them, in black lettering on white, are the words "Elizabeth Catlett / A Black Revolutionary Artist / Una Artista Negra Revoluciona[ill.]."](https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/word-image-20529-1.jpeg)

The galleries followed a primarily thematic, loosely chronological organization that addressed the central ideas that animated Catlett’s life and work. Explanatory wall text introduced the sections “The Personal as Political,” “Roots and Awakenings,” “Prints for the People,” “El Pueblo,” “Global Solidarity and Ancestral Legacies,” “Motherhood and Family,” and “Black Women.” A highlight of the first gallery included the prominent display of the full suite of prints in Catlett’s foundational Black Woman series, which explicitly champions the myriad intellectual, creative, political, and mundane actions of Black women that have enriched the fabric of modern life. Catlett cared to represent the multiplicity of Black women so often overlooked, flattened, exaggerated, or demonized in visual culture. It was apparent that the curatorial team thought carefully about ways to expand visitors’ understanding of Catlett in all her own multiplicity as an artist, activist, teacher, one-time student, and loving wife and mother. Throughout the exhibition, community labels written by Catlett’s former students, family friends, and contemporaries accompanied select artworks, providing authorial perspectives beyond the typical (singular) museological voice. Vitrines housed ephemera that spoke to Catlett’s creative influences and surroundings; these objects included, among others, a Gordon Parks photograph, a Richard Wright novel, a photograph of her art club at Howard, and a brochure of the community classes she offered at the George Washington Carver School. All these items established the broader tradition of the progressive, socially engaged Black art communities within which she learned and worked.

The “Roots and Awakenings” gallery primarily exhibited Catlett’s student work—from design work completed under Loïs Mailou Jones’s tutelage at Howard to early paintings in watercolor, gouache, and pastel. A photograph of Negro Mother and Child, the stone sculpture (now lost) she had submitted for her master’s thesis at the University of Iowa in 1940, provides evidence of Catlett’s developing, sophisticated eye for compact, reduced form, sinuous contour lines, and architectonic planes that continued to typify her work in both print and sculpture. The two-figure composition of a monumental woman wrapping an infant child in a close embrace—evocative of religious scenes of the Virgin Mary and Christ—became prototypical for Catlett.

Her recurrent iterations on the theme of Black motherhood (highlighted in the later gallery “Motherhood and Family”) addressed the profound intimacy of Black maternity in tandem with its overwhelming terrors. In the powerful print Torture of Mothers (1970), for instance, Catlett appropriated an image of a wounded Black boy, a victim of police brutality, from an issue of Life magazine. Lying prone in a bloody inferno, the boy’s body stretches across the length of a woman’s head in profile, operating as a visual representation of the fearful preoccupation experienced by Black mothers concerned for the safety of their children. Torture of Mothers, in addition to other works on display, imparts Catlett’s incisive commentary against the state violence experienced globally by youths of color.

The third gallery, “Prints for the People,” explores Catlett’s initial residency at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a leftist print collective in Mexico City that she joined as a guest while traveling on a Julius Rosenwald fellowship. Less than a year later, due to shared values on collective political action and the social utility of freely accessible art, she joined as a permanent member. The TGP’s prints, which were collaboratively produced, cheaply made, and distributed directly to the people, addressed a wide range of sociopolitical inequities and global conflicts, from workers’ and Indigenous rights in Mexico to anti-Blackness, antifascism, and anti-imperialism. Other members of the collective, including Alberto Beltrán, David Alfaro Siquieros, Francisco Mora (Catlett’s future husband), Mariana Yampolsky, Pablo O’Higgins, Fanny Rabel, Celia Calderón, Francisco Luna, Guillermo Rodriguez Camacho, and guest artist Margaret Burroughs had work displayed in the exhibition.

Catlett received Mexican citizenship in 1962, but due to her history of political activity, she was deemed an “undesirable alien” by the United States and denied entry to the country for over a decade. Catlett maintained her connection to the United States through her art, supporting and reflecting on the Black revolutionary wave through several key pieces on display in the “Ancestral Legacies and Global Solidarity” section of the exhibition. The 1971 sculpture Political Prisoner, created in response to the arrest of Angela Davis, anchored the space. The figure’s manacled hands are not visible when viewing the sculpture from the front, where Catlett prominently painted the Pan-African tricolor flag, a symbol of Black liberation. The figure’s upright posture and upturned gaze strike a picture of hope, resolute determination, and defiance—undercurrents that were present throughout the majority of the work in the gallery. Examples like the sculpture Mask for Whites (c. 1970) and the print Vendedora de periódicos, Collage Version (c. 1958/75) exhibit Catlett’s increased use of collage as an opposition technique, collecting newspaper clippings from the Black Panther newspaper, Mexican periodicals, and other sources that lambasted police and state brutality, fascism, and imperial overreach in the United States and other authoritarian or colonial regimes. The exhibition underscored Catlett’s understanding of the interlocking and interrelated demands of global liberation.

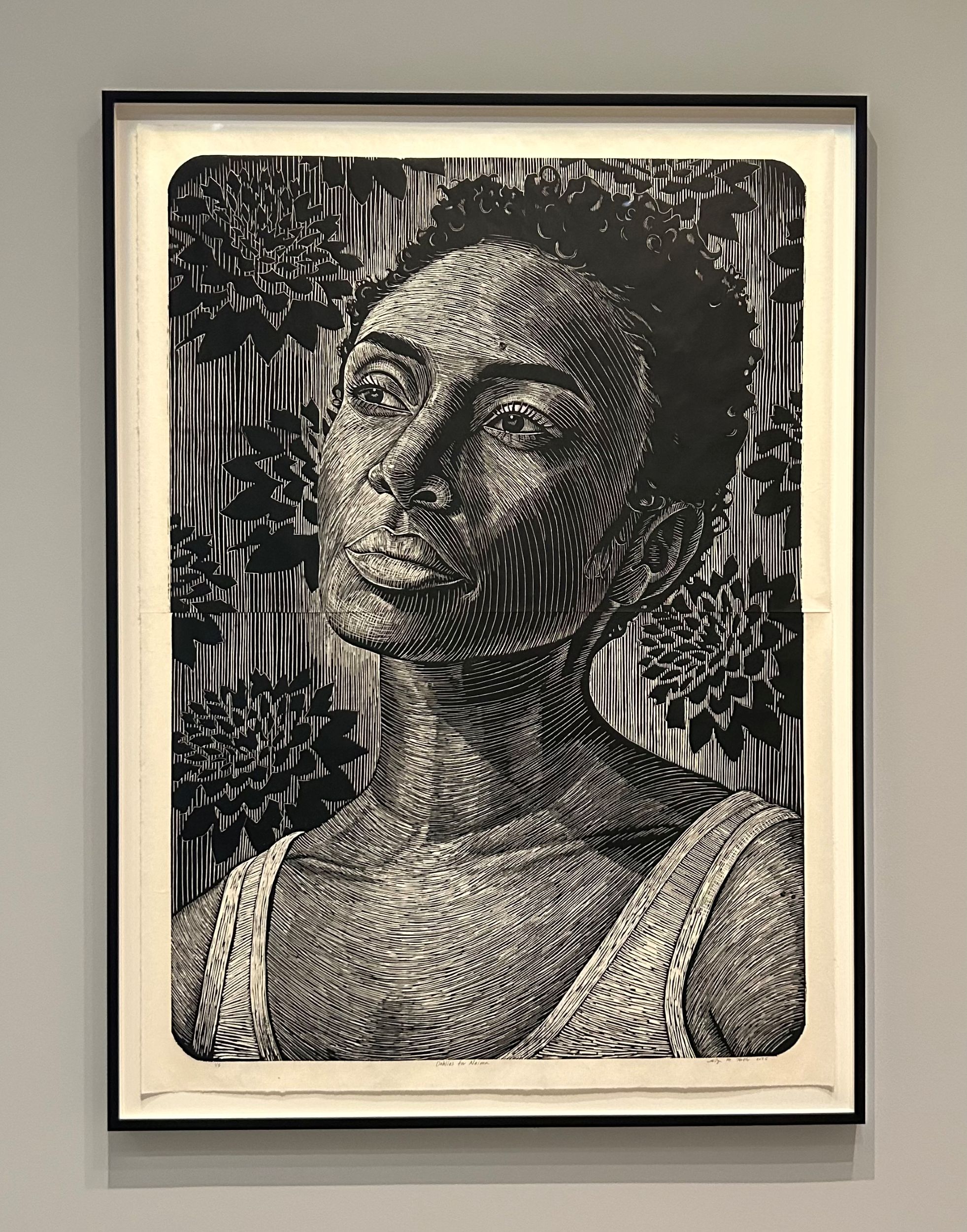

A small auditorium adjacent to the first gallery screened two films. La Obra de Elizabeth Catlett (The work of Elizabeth Catlett), created by Catlett’s son Juan Mora Catlett in 1977, documents the creation, fabrication, and installation of Catlett’s sculpture of Louis Armstrong in New Orleans, overlaid with Catlett’s reflections on the value and necessity of art. The other film, Print Like a Great: Elizabeth Catlett featuring LaToya Hobbs, was produced by the National Gallery of Art to accompany the exhibition. It chronicles Hobbs, a contemporary printmaker and portraitist who claims Catlett as one of her artistic idols, on a research trip to Mexico in preparation for the creation of Dahlias for Naima (fig. 2), a monumental woodcut portrait of Catlett’s granddaughter that was commissioned for the exhibition. An abridged version of the film showcasing the process was screened in the gallery next to the piece. While Catlett’s own work, Naima: My Granddaughter (fig. 3), a portrait bust modeled when Naima visited her grandparent in Cuernavaca as a teenager, was included in the last gallery of the exhibition, it was a regret that the pieces were not installed next to each other. Taken together, the two artworks provide a poignant image of Catlett’s maternal and artistic legacies that continue to flourish in her memory.

The exhibition catalogue, Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies, is essential reading. It offers a collection of critical scholarly essays by leading voices in Black American, Mexican, and feminist art histories, as well as a compendium of new and updated reproductions of her artwork. In it, curator Dalila Scruggs describes Catlett as pursuing the “mutually reinforcing” pillars of social justice and formal rigor in her work, eschewing the discourse of her time that claimed art should either be for art’s sake or serve a social purpose—not both.4 This vital exhibition affirmed that Catlett pursued both tracks with precision and great accomplishment, producing a body of work across sculpture, print, and paint that made no compromises in either form or content. While rightfully celebrating Catlett’s achievement by all standard metrics, Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist simultaneously honors Catlett by the standards she set for herself, highlighting her dogged community spirit and her commitment to creating an accessible, legible, and democratic art dedicated to the peoples she claimed as her own.

Cite this article: Ebonie Pollock, review of Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 2 (Fall 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.20529.

Notes

- Gwendolyn Bennett, foreword to Paintings, Sculptures, and Prints of the Negro Woman by Elizabeth Catlett (Barnett-Aden Gallery, 1947), n.p. ↵

- Elizabeth Catlett, “The Role of the Black Artist,” Black Scholar 6, no. 9 (1975): 12. ↵

- Catlett, “Role of the Black Artist,” 12. ↵

- Dalila Scruggs, “To That Degree and More,” in Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies, ed. Dalila Scruggs (University of Chicago Press in Association with the National Gallery of Art and Brooklyn Museum, 2024), 12. ↵

About the Author(s): Ebonie Pollock is a doctoral candidate in the History of Art and Architecture department at Harvard University.