Encountering Edmonia Lewis in the Correspondence of Florence Freeman

PDF: Sienkewicz, Encountering Edominia Lewis

The sculptor Florence Freeman (1836–1883), writing from Rome to her family in Boston, offers a firsthand account of the arrival of Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907) in the Eternal City in December 1865: “She . . . came directly to us next morning, having a letter to Miss Williams, who went out with her at once and before the end of the day had established her in a cozy little apartment, and engaged a studio.”1 Lewis was expected, her needs were efficiently met, and she soon joined Freeman and others for Christmas dinner. For a period, Lewis and Freeman interacted regularly, as recorded in Freeman’s correspondence. Freeman brings Lewis to life as a vibrant and gregarious member of Rome’s international artist community. I will here offer full transcriptions and initial analysis of all mentions of Lewis in the Freeman archive.2 My concern is primarily with providing access to this important new resource on Lewis, which expands our understanding of her personal and professional networks while also revising key facts about her first months in Italy. I also position these findings within current scholarship regarding artists’ networks, transnational artistic communities, and the “sisterhood of sculptors” active in Rome in the second half of the nineteenth century.

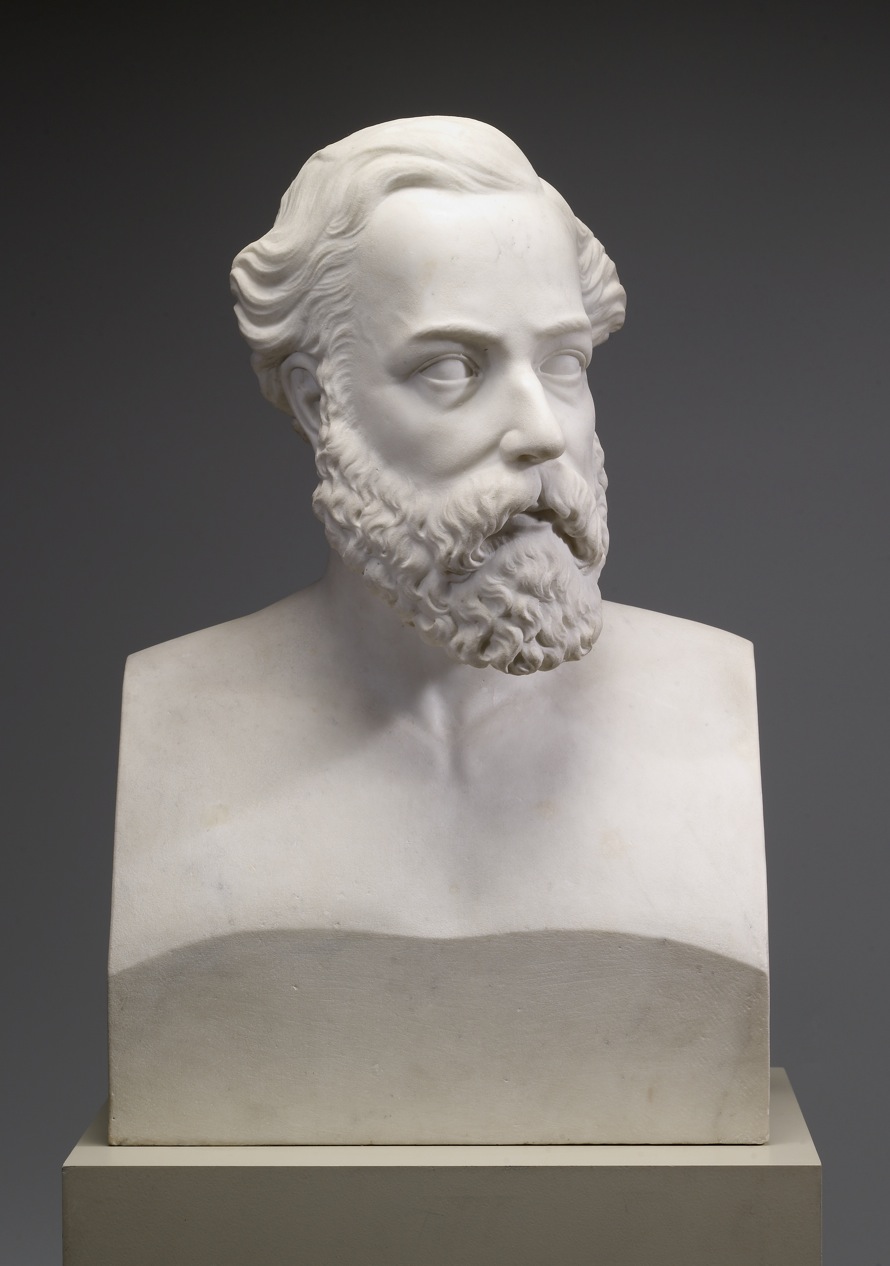

Among the American women sculptors working in Rome in the 1860s and 1870s, Lewis has drawn significant attention, despite severe limitations in documentation (fig. 1).3 Lewis, a mixed-race artist of Black and Indigenous (Chippewa/Ojibwe) ancestry, has been the subject of scholarly and popular attention in recent years, yielding new biographical data, even as much remains unanswered and, perhaps, unanswerable.4 As scholars have sought to interpret Lewis’s significant legacy, often through the lens of race, they have struggled with the problem of the archive on either side of the Atlantic. Unfortunately, Lewis’s own voice, including the specific ideas, values, and arguments elaborated in her important sculptural works, still largely eludes scholars. Fundamental questions, such as how Lewis balanced her biracial identity or her position on women’s rights, have been gleaned primarily from visual analysis and scant archival traces.5 Given this dearth of information, the identification of new primary sources on Lewis is noteworthy.

Florence Freeman’s letters, which include substantive information regarding Lewis’s first months in Rome, were donated to the Boston Athenaeum in 2022.6 The gift consisted of three boxes containing nearly three hundred letters (double-sided and on tissue paper) from Freeman, who used the name Flori, to her parents and siblings.7 Although I was unfamiliar with Freeman prior to encountering this archive, these personal letters gave me a great sense of her personality, artistic ambitions, and daily activities. As soon as Freeman mentioned Lewis, I realized I had a valuable glimpse into the personality and lifestyle of a renowned, if often elusive, figure. Freeman’s comments present a fairly intimate assessment of Lewis. They revise the chronology of Lewis’s arrival in Rome, offer new details about her relationships in the expatriate Anglophone artist community, and provide information about her first experiences in Rome.8

Freeman lived in Italy from 1862 until her death in 1883, returning to the United States only for brief visits.9 Her artistic output was limited, and none of her works have been identified in museum collections. Prior to the donation of this correspondence, Freeman was reintroduced to scholars in a 2022 article by Jacqueline Musacchio.10

I do not attempt to exhaust the many research directions concerning Freeman that are now possible due to the information contained in her correspondence at the Boston Athenaeum. The Freeman letters are a rich source of robust new evidence for multiple topics, especially the Anglophone community of women creatives in Rome. Freeman’s letters discuss her near-daily activities with Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908), whom she called “Hattie” and with whom she was closely associated for several years. She also mentions many other British and American women artists and travelers, including Emma Stebbins (1815–1882), whom she called “Aunt Emma,” and Stebbins’s partner, the actor Charlotte Cushman (1816–1876). Freeman also mentions many other unknown or little-known women in the arts and provides significant information about her male teachers and mentors, including Thomas Ball (1819–1911), John Gibson (1790–1866), Richard Saltonstall Greenough (1819–1904), and Hiram Powers (1805–1873). Among the fields that the archive enriches are women’s history, LGBTQ+ studies, fashion history, music history, photography history, Italian-American studies, and even Indigenous studies.

Freeman’s mentions of Lewis, which occur between December 1865 and July 1866, are a limited component of the archive, yet they revise key details of Lewis’s crucial first months in Rome while offering a sympathetic first-person account of Lewis’s open, sociable personality. Freeman’s first mention of Lewis appears in a letter begun December 5, 1865, when Freeman writes, “Miss Lewis has decided to come to Rome I believe.”11 Clearly, Lewis was already known to the Boston Freemans and subsequent mentions confirm that Lewis knew the family personally, perhaps unsurprising given their prominence in Boston society and their interest in sculpture. Freeman’s family may have alerted her to Lewis’s plans to visit Italy.

Freeman’s update alludes to the networked Anglophone community across the Italian peninsula, whose members communicated via word of mouth and correspondence. Almost certainly, Freeman had received updates on Lewis’s activities in Florence, where she had been for several months, receiving some degree of mentorship from Powers and Ball.12 A minor transatlantic scandal had erupted when Lewis believed she had been refused entry, despite a letter of introduction, when she attempted to call on Elizabeth (Lizzie) Adams (1825–1898), another expatriate American artist. A flurry of correspondence between Boston and Florence attributed the incident to a mistaken address, though perhaps Lewis remained unconvinced.13 Freeman was close to Adams, both in Florence and Rome.14 Her letters do not mention the incident, but she likely knew of it.15 Freeman and her friends may have made an effort to ensure that Lewis’s reception in Rome was better than in Florence, given her prominent advocates in Boston society.

While Freeman’s specific source for Lewis’s plans is omitted, she conveys the update along with news of another friend—a “Miss Foley.” Margaret F. Foley (1827–1877) was a fellow artist and frequent associate of Freeman’s.16 Freeman indicates that this source wrote to her about Foley, and the same source likely offered the update on Lewis, but without any certainty of when she would move on to Rome.

In a letter to her family from Christmas day 1865, Freeman announces Lewis’s arrival alongside her holiday greetings:

I wonder what you are doing about this time? I need not wonder—though, for I can easily guess, I think. With us it is half past nine, so you are doubtless just preparing to enjoy your Christmas dinner. We finished ours some two hours ago, and the turkey and plum pudding were excellent. Who do you think made the fourth at our table, but little Miss Lewis, our colored sister. She arrived about a week since from Florence, and came directly to us next morning, having a letter to Miss Williams, who went out with her at once and before the end of the day had established her in a cozy little apartment, and engaged a studio. We like her very much and find her very interesting and sensible. She is delighted with Rome, and already feels more at home than in Florence. Yesterday she went to church with us.17

As per this letter, Freeman places Lewis’s arrival around December 17, 1865, earlier than previously thought.18 Enjoying Christmas dinner together were Lewis, Freeman, Mary Elizabeth Williams (1825–1902), and Abigail Osgood Williams (1823–1913).19

Hosmer has been credited with helping Lewis find a studio, but Freeman stipulates that “Miss Williams” saw to this, and she would certainly have credited Hosmer if appropriate. Perhaps Hosmer helped Lewis at a later date, but Freeman does not mention Hosmer as particularly engaged with Lewis.20 Instead, she credits one of the Williams sisters with welcoming Lewis, securing both her lodgings and studio. Freeman lived with the Williamses during her first years in Rome and remained close with them after they no longer shared lodgings. Both Williams sisters were artists and abolitionists. It makes perfect sense that Lewis would be directed to them with a letter of introduction.

Freeman asserts that Lewis was already more “at home” in Rome than she had been in Florence. Scholars have suggested that Roman society was more racially open and socially permissive than Florence (and likely more so than most cities in the United States).21 Still, Rome’s microsociety of expatriate Bostonians may have initially been more vital to Lewis’s comfort than the city’s larger society.22 Freeman’s letters are filled with constant references to members of Boston society, and Lewis, though exceptional in significant ways, was a member of this social set.23 The Williams sisters and Freeman quickly ensured that Lewis was included in their social network and introduced to some of the city’s collections. Of course, they probably also treated Lewis differently than they did one another. This difference is signaled by Freeman’s reference to Lewis as “our colored sister.” Although Freeman meant such statements to show support, they still exemplify the inequalities Lewis endured.24

Later in January, Freeman mentions Lewis as part of her regular visiting rounds along the Via Margutta and Via del Babuino: “This morning I went up to Hattie’s to breakfast, which of course I enjoyed. Afterward we went in to see Miss Lewis, then to Miss Cushman’s for a little while. Also to see Mrs. Crow. Then, stopping at Hattie’s new studio, it was about eleven when we arrived at number five.”25 Freeman’s daily routine involved spending time with Hosmer, frequently for breakfast, and visiting at each other’s adjacent studios. Periodically, Freeman (often with Hosmer or others) would visit other studios in the neighborhood. On this occasion, the calls may have been primarily social, to either lodgings or studios, as no specific artworks are mentioned. This is the only time Freeman documents direct contact between Hosmer and Lewis.

Later that week, Freeman returns for a longer, preplanned, visit with Lewis:

In the evening, I had arranged to go to Miss Lewis, so left Hattie rather early. Miss L. is very comfortably settled in her little parlor and bedroom.26 The Miss Williamses were there and she gave us some tea, so we had a nice little evening with her. There has been some delay in getting her box of casts through the customs house,27 so she has not been able to begin work yet, but she seems a cheerful little body, and does not allow things to worry her.28

Freeman’s description of Lewis as a “cheerful little body” can read as condescending, though it also refers to Lewis’s small stature—mentioned elsewhere by Freeman and others. The Williamses are there socializing with Lewis, continuing to help her feel welcomed and settled in Rome. Freeman, the Williams sisters, and Lewis enjoy a “nice little evening” together in Lewis’s lodgings, proving that Lewis had already created a domestic environment deemed sufficient to entertain these upper-crust women.

In January 1866, John Gibson experienced a serious health event, which led to his death about two weeks later.29 Gibson’s illness disrupted Freeman’s life substantially, perhaps contributing to her failure to thrive as a sculptor in Rome.30 Lewis may have hoped to join Hosmer and Freeman as Gibson’s mentee, but this was not to be. She may have met Gibson before his illness, but any contact would have been minimal, especially since he was also ill earlier in the month. During his sickness, Hosmer focused almost exclusively on caring for Gibson. Freeman visited Gibson a few times but did not participate in active caretaking, instead worrying about its strain on Hosmer.31

Meanwhile, life went on for Freeman, including working in her studio and socializing. She was not spending her usual long hours with Hosmer and may have had more free time as a result, including opportunities to visit with Lewis, as she reports:

Miss Lewis came in this evening while we were at dinner. She said she felt rather lonely so thought she would come and see us. She had dined, so she waited for us and stayed part of the evening. She was very anxious that we would dine with her so we went last Sunday. She gave us a very excellent dinner, and seems very cozy in her little apartment. In the evening she took out her guitar and played and sang a little for us.32

This passage captures Lewis’s personality beyond first impressions. Lewis is sociable and an excellent hostess, providing good food and entertainment.33 She participates readily in social routines, demonstrating knowledge of hosting etiquette.34

A third visit that week brings a professional update: “Miss Lewis came in to see us yesterday. Having got her cases from the custom house, she is settled in her studio and seems quite contented and happy. She is a nice little thing and we like her very much.”35 Delayed nearly a month, Lewis’s art supplies finally arrived and were immediately brought into her studio, where Lewis would have both worked and entertained. Sculptors’ studios in Rome were social, semipublic spaces. Lewis was outgoing by nature, and her career was subject to transatlantic attention, so she likely prepared for an influx of visitors. Now, she was ready to launch her professional life in Rome in earnest.

Lewis and Freeman became confidantes, as evidenced by their next interaction. Surprising news arrived in a family letter: to Freeman’s surprise, her sister Sue was engaged. Shortly after learning the news, Freeman received a visit from Lewis and shared it, later recounting: “Miss Lewis was here just after I had read my letter, so I told her the news it contained. She said she did not know what to say about it but she thought she [Sue] was too pretty to be married. Miss Lewis asked me to give you her kind regards, as she supposed it would not do to send her love. I told her you would like that better though, and I should send it.”36 This anecdote reveals a careful social balance. Lewis essentially offers no comment on Sue’s engagement, while complimenting her good looks. She also sends her kind regards while taking care to show deference. Freeman, meanwhile, encourages Lewis to freely express her “love” for the Freemans. Such social acrobatics reflect the contortions of polite interactions—which were no doubt more complex for Lewis, whose racial background made social exchanges less predictable. Freeman frequently mentions differences in the social mores among the expatriate community in Rome from society in Boston. These differing expectations might have presented both extra complexities and unexpected, perhaps liberating, opportunities for Lewis.

Freeman’s next mention records Lewis’s first visit to the Vatican Museums:

We thought we would make some little variation from our usual occupations to mark the day, so we went to the Vatican.37 Miss Lewis came and breakfasted with us, and we had our flag on the table. Miss Lewis went with us to the Vatican, it was her first visit there, and of course she enjoyed it much, though she was very tired, as we went both to the picture and sculpture gallery. Then we came home with good appetites and it being late we made our lunch a sort of dinner.38

It is somewhat surprising that Lewis waited two months to visit the Vatican Museums, but the delay may have been due to closure for the Christmas season or to Lewis’s prioritization of establishing her studio and preparing for the efficient production of saleable marbles as soon as her casts arrived.

A month later, Lewis hosted another dinner party, which Freeman described in her letters of March 1866:

I have not told you of our visit to Miss Lewis the other evening. She is very social in her feelings and likes to have a few friends come. She is very generous, and with her Indian ideas of hospitality, she could not be content with having only a cup of tea and some little cakes, so she had chicken salad, toasted muffins, cakes and preserves, and afterward lemonade. We had a very pleasant evening. Mrs. Freeman and her niece were there, they play and sing together very nicely with the guitar. Mr. and Mrs. Brandt and Mr. Steingel too were there, so we had some delightful little German songs.39

Lewis was beginning to cultivate a larger community in Rome. Freeman characterizes Lewis’s generosity with the expression “Indian ideas of hospitality,” likely intended as a compliment but one relying on racial stereotypes. Freeman was a fairly withdrawn person and clearly admired Lewis’s ability to host a “nice evening” and gather friends around herself. Shortly thereafter, Freeman recounts her own reception of guests: “In the evening the Miss Williamses and Miss Lewis came up when we had some refreshing ice cream and cakes.”40 Though not as lavishly, Lewis’s hospitality was reciprocated.

From Freeman’s account, details emerge regarding the expatriate society in Rome. Lewis’s menu is tailored to American tastes, featuring items distinct from those served by Roman landlords and Italian servants. Freeman’s letters record elsewhere that expatriate women prepared such dishes themselves, ensuring the accuracy of recipes and cooking technique. Though unstated, Lewis herself may have prepared the meal. Also interesting is Freeman’s mention of German-speaking guests, a valuable reminder that American artists, including Lewis, socialized with Rome’s larger community.

In another letter of mid-March 1866, Freeman discusses Lewis’s artistic progress:

Yesterday morning I went to Miss Lewis’ studio. She is getting on very well. She has modelled a smaller bust of Colonel Shaw and is now-doing [sic] two little groups of indian subjects that are very nice. She has a great deal of perseverance and application in addition to her love for her work and I think she will be sure to get on well. I gave her your message and the remembrance pleased her much. We see her quite often and like her much. She often stops in on her way to the studio. In the morning she dines with us today I saw her and Mrs. Ball last evening. I hope they will decide to come back here for next winter and think they will.41

The following week, Freeman sacrificed her own studio time, because, she states, “I had gone to see Miss Lewis who was not very well.”42 A few days later, she writes, “Yesterday I went to Miss Lewis’s studio. She is getting on very nicely with her work. She is doing two very pretty little Indian groups, the wooing and marriage of Hiawatha.”43

Freeman’s comment is perhaps the earliest to mention the Hiawatha sculptures now among Lewis’s most renowned productions (figs. 2–3). She praises Lewis’s strong work ethic and passion for sculpture, characteristics that Freeman elsewhere foregrounded about herself. These endorsements of Lewis’s efforts counter criticisms from Lydia Maria Child (1802–1880) and others in Boston, who stated Lewis should have spent more time perfecting her art before producing marbles for sale.44 Freeman is silent on the aesthetic aspects of Lewis’s sculptures, instead discussing Lewis with camaraderie as a peer. By contrast, Freeman’s commentary on Hosmer’s or Stebbins’s works typically is glowing in its admiration of their acknowledged prowess.

Interestingly, before Lewis’s arrival, Freeman began a work titled Chibiabos, first mentioned by name in January 1865.45 Chibiabos also represented a character from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha.”46 By December 1865, Chibiabos was visible in Freeman’s studio, likely in plaster. Chibiabos, though lost, offers a contextual comparison for Lewis’s Hiawatha sculptures, perhaps opening the opportunity to consider more deeply the influence of the Roman art community on her works.47

Freeman mentions seeing Lewis “frequently” and notes they regularly breakfasted together, which would place Lewis in the daily routines of Cushman and/or Hosmer, as Freeman generally ate with one of them. With studios nearby and shared daily routine, the artists were deeply involved personally and professionally.48 The next mention, however, distances Lewis from Freeman.

Several weeks pass without mention of Lewis; then a letter dated late June through early July 1866 reports: “I have not seen Miss Lewis again but she was better and going to Tivoli for a few days. I was told yesterday that she had become a Catholic, under the influence of Mrs. Cholmeley, who is of that faith. I have not heard it from herself so do not repeat it, though I think there is no doubt it is true. It seems a rather sudden conversion.”49 Lewis has gone from seeing Freeman frequently to sporadic interactions. Scholars have already noted the association between Isobel Cholmeley (b. 1830s) and Lewis, including that Cholmeley completed a bust of Lewis (location unknown).50 Lewis may have become distanced from Freeman’s circle as she was drawn into the orbit of Cholmeley. Might Boston and its influence have lost its hold on Lewis? Could there have been a falling out between Freeman (or another member of her circle) and Lewis? Or was increasing closeness to Cholmeley the reason for growing distancing from Freeman (and likely, by extension, Cushing and Hosmer)? No doubt, Cholmeley had existing relationships, and perhaps rivalries, among this community. Perhaps the change in habits was due to, or exacerbated by, the departure of the Williams sisters from Rome. By the end of May 1866, they had left the city, and Freeman moved closer to Hosmer.

Scholars have long been aware that Lewis was Catholic and, more recently, that she joined the Catholic Church while in Rome, although a firm date was not known.51 In a moment when Rome was the sole holdout from Italian unification, Catholicism was both a religious and political mantle. Lewis may or may not have followed the complex politics of the Risorgimento (the process of forming the unified nation of Italy) but conversion to Catholicism would have opened up opportunities for her in Rome.52 Conversely, many Americans were critical of Catholicism, some to extreme degrees.53 Catholic faith could have hurt Lewis’s ties to many American patrons, while it tightened other connections.

Personal tragedy struck the Freemans in fall 1866, when the youngest Freeman child, Marion, died. Flori suffered greatly from the loss. Her last mention of Lewis occurs after Marion’s death, in a November letter: “My friends have all been to see me and have been very kind, but there are times when one must be alone, and even those who are dearest to you can do little for you. Hattie sends much love to you, and kindest sympathy. Miss Foley and Miss Lewis also send very kind remembrances.”54

Freeman and Lewis continued to live in Rome for more than a decade, yet Lewis disappears from Freeman’s letters, with two likely causes of this distance. First, Freeman’s life went through radical changes. After Marion’s death, Freeman withdrew at length from society, eventually choosing a much more limited circle. This constriction was exacerbated by her father’s death in 1869, which significantly reduced Freeman’s finances and her family’s ties to Boston. In another blow, Freeman suffered a prolonged, severe illness that, among other things, resulted in losing all her hair and retreating further from society. Gradually, Freeman’s sculptural activity dwindled to nothing, with financial and physical limitations leading her to switch to painting and close her studio. Second, the departure of the Williams sisters from Rome for an extended period between 1866 and 1867 may have been another direct cause for Freeman’s distance from Lewis. With Freeman no longer residing with the Williams sisters, either she or Lewis would have had to proactively extend the acquaintance—something perhaps neither pursued. Notably, if Lewis’s relationship with Hosmer had been close, she would have continued to see Freeman regularly. Still, her total silence on Lewis seems striking, given the frequent mentions from December 1865 to July 1866. The possibility of acrimony between Freeman and Lewis cannot be ruled out.

Taking Freeman’s mentions of Lewis in sum, some preliminary conclusions emerge about their significance. The Athenaeum collection offers some factual corrections about Lewis’s first months in Rome. Previous scholarship has presented Hosmer and Cushman as the primary figures who welcomed Lewis to Rome and promoted her work. Here, instead, Lewis’s first friends are shown to be the Williams sisters and Freeman. These three women were a support network for Lewis. They were available when she was lonely, and they exchanged hospitality with her. When Lewis was sick, they checked on her. The Williams sisters offered significant practical help. They found Lewis her first housing in Rome and secured a studio for her—no small feat, as studios were in short supply. Although it has been said that Lewis’s first studio in Rome was Gibson’s, this is clearly not the case. Gibson was alive and using his studio when an initial studio was secured for Lewis.55

More broadly, Freeman’s letters invite some consideration of where other previously unidentified resources might exist regarding Lewis’s life and career in Europe. Freeman’s correspondence reminds scholars that many figures, especially women, in the artistic and social circles between Boston and Rome remain poorly known. While some archival collections will certainly still be rediscovered in descendants’ attics (as was the case with the Freeman letters), others, like that of the Williams sisters, await attention.56 The correspondence of female travelers in Italy has not been systematically explored, and scholars searching for Lewis may find many other gems if they cull through the correspondence and diaries of American and European women. I identified one such additional nugget, recorded in a journal by Bostonian Eunice Maria Faxon Weeks on April 20, 1866: “We went to Miss Lewis (the Colored girl) to see her groups of Hiawatha etc wh[ich] I think disclose much genius. She is not generally rec’d in society, although many sensible persons accept her.”57 Many who associated with Lewis were women, whose materials are less likely to have been collected. Still, careful combing of travelers’ diaries may yield further valuable evidence of Lewis’s activities.

Freeman’s letters document that Lewis’s associates went beyond the American community, including British and German friends. She may have had associates from many different backgrounds. Lewis never returned to live in the United States. Gaining deeper understanding of her career might require further consideration of Lewis as an expatriate and/or transnational artist. While clearly the struggle for abolition and the representation of Indigenous figures were significant American motifs in Lewis’s oeuvre, other lesser-known works, like Bust of Dr. Dio Lewis (fig. 4) or Young Octavian (fig. 5), refer directly to the influence of Rome and Roman art objects on her artistic practice and merit reassessment from a transnational perspective. Freeman’s letters hint that deeper probing of Roman, Parisian, and London networks may reward researchers with additional details about Lewis. These mentions also underline the important point raised by Kirsten Pai Buick that Lewis’s religious works deserve greater consideration in light of her conversion to Catholicism and its impact on her life and career in Rome.58 Freeman characterizes Lewis as highly sociable. Lewis may not have sat at home in the evenings like Freeman, producing a large archive of correspondence for perusal by later historians. But, given her high level of participation in Roman society, it may be possible to trace her activities through other acquaintances who, like Freeman, may illuminate key details of Lewis’s life.

Cite this article: Julia A. Sienkewicz, “Encountering Edmonia Lewis in the Correspondence of Florence Freeman,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19927.

Notes

The author would like to thank the Boston Athenaeum for the permission to publish these archival transcriptions and for the award of a Caleb Loring Jr., fellowship that led to the research discussed in this article. Special thanks to Mary Warnement and all the Special Collections team at the Boston Athenaeum. This research was also supported by the resources of the Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo Professorship at Roanoke College.

- Anne Freeman to her family, December 25, 1865, box 2, folder 113, Anne Florence Freeman Letters, MSS.L840, Boston Athenaeum (hereafter “Freeman Letters”). All quotations from this archive are based on my own transcriptions and printed here courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum. ↵

- Although there are only three boxes of material, the letters are challenging to read and written on delicate, semitransparent tissue paper. Given this, it is possible that other mentions of Lewis may still be identified in the archive. Fortunately, the Boston Athenaeum archivists indicate that the collection is likely to be published in full in coming years. ↵

- For the most complete history of this artists’ community, see Melissa Dabakis, A Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014). ↵

- The year and location of Lewis’s death, for example, was only uncovered in 2011. See Dabakis, Sisterhood of Sculptors, 255n14. ↵

- On the challenges of filtering sources about Lewis, see Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject (Duke University Press, 2010), 11–18. For example, Buick provides a historiography of the differing interpretations of Lewis’s work Forever Free based primarily on formal analyses (50–58). ↵

- This substantive archival collection presents only one side of the correspondence. The letters that Freeman received are not included and likely do not survive. Though she makes mention of many letters sent and received with other friends, none of these are included in the collection either, though a few letters from Freeman’s friends to the Freeman family in Boston are in the collection. Presumably, after Freeman died in Rome, any correspondence that she had retained met with a different fate than the archive preserved by her family. ↵

- Researchers wishing to consult the papers will find a typescript at the start of box 1 with a few sentences of summary for each letter, including some of the individuals mentioned. Lewis’s name is flagged in this typescript, a fact that greatly assisted my review. Despite my attempts to fully identify the scope of Lewis’s presence in the letters, other mentions of Lewis may emerge as subsequent scholars work with the collection; see note 2, above. ↵

- I refer to the Anglophone artist’s community here, because Freeman’s interactions were largely confined to American and British residents or tourists. It is unclear how well she mastered the Italian language, even with many years of residency in the city. Her comments about the people of Italy, as a general rule, were othering rather than understanding. ↵

- The Freeman Letters contain materials spanning 1852 to 1897, reflecting some documents from before Freeman’s departure for Rome and following her death. The biographical dates stated here are drawn from materials in the Freeman archive. ↵

- Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, “Finding Florence Freeman,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 1 (2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.1.4. ↵

- Freeman to her family, December 5, 1865, box 2, folder 112, Freeman Letters. Most of Freeman’s correspondence is to her mother, but it is clear she expected the letters to be read by others in the family (and perhaps more broadly). Occasionally, letters are specifically addressed to her father or siblings. ↵

- Looking at Ball’s memoir, some sources have viewed a section of tips, beginning “This is for the benefit of beginners,” as a reflection of the type of information he might have given to Lewis. See Thomas Ball, My Threescore Years and Ten: An Autobiography (Roberts Brothers, 1891): 179–80. ↵

- See Harry Henderson and Albert Henderson, The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis: A Narrative Biography (Esquiline Hill, 2012), bk. 2, ch. 1. On Adams, see Nancy Carlisle, “Artful Women” Historic New England (Fall 2020), https://issuu.com/historicnewengland/docs/hne.fall2020final/s/11837303. ↵

- Adams found Florence more congenial and returned after a year in Rome, but it was her relocation to Rome that inspired Freeman to take the leap and move south. ↵

- Sometimes Freeman included small scraps of letters on sensitive topics, which her family saved with her letters. There may well have been others that they destroyed. The Freemans shared extensively with one another regarding anything and anyone that had to do with Boston society, and it is reasonable to assume that a member of the family either in Boston or in Rome had become aware of the tension. ↵

- On Foley, see Dabakis, Sisterhood of Sculptors, 87–90. In Freeman’s letters, she is generally referred to as “Peggy” or “Peggie.” ↵

- Freeman to her family, December 25, 1865, box 2, folder 113, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Newspaper accounts record Lewis as beginning to establish herself in Rome by March 1866. See “Our Negro Sculptress in Rome,” Springfield Weekly Republican, March 31, 1866; and a much-quoted letter to the editor by Lydia Maria Child in the New York Independent, April 5, 1866. Marilyn Richardson also cites the arrival in Rome of Lewis “by spring 1866”; in “Friends and Colleagues: Edmonia Lewis and Her Italian Circle,” in Sculptors, Painters, and Italy: Italian Influence on Nineteenth-Century American Art, ed. Sirpa Salenius (Il Prato, 2009), 103. ↵

- On these people, see the Peabody Essex Museum’s biographical sketches for the Mary Elizabeth Williams Papers, 1830–93, MSS 253, https://pem.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/644 (hereafter “Williams Papers”). ↵

- Much heed has been paid to a quotation from Lewis in Child’s 1866 letter to the editor, praising Hosmer and crediting her with welcoming Lewis and settling her into her studios. In reality, these claims may have been made (and/or published) in order to associate Lewis with the headline figure among Rome’s “sisterhood of sculptors.” The generosity and efforts of the Williams sisters would have received a lot less interest among readers in 1866. Buick similarly expressed skepticism of Hosmer’s support for Lewis; in Child of the Fire, 64. ↵

- This point is discussed in both Dabakis, Sisterhood of Sculptors, and Buick, Child of the Fire. It is important to also note, though, that the Papal States, of which Rome was the capital, were highly conservative and strictly regulated under the power of the Pope. Cosmopolitanism in Rome had its limits. ↵

- For more on the role of Boston society on the artist’s community in Rome, see Dabakis, Sisterhood of Sculptors, 16–36. ↵

- The Freeman Letters include many references to friends and acquaintances who visited both the family in Boston and Freeman herself in Rome, all within a matter of months. The family circle of acquaintances expanded to incorporate friends and associates first made in Rome, who would then visit Boston, and vice versa. ↵

- Scholarship regarding Lewis’s career has examined other instances of the racism that was often built into the behaviors of her white supporters. See, for example, Buick’s discussion of Child in Child of the Fire, esp. 67, 178. ↵

- Freeman to her family, January 7, 11–13, 1866, box 2, folder 114, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Freeman’s correspondence with her mother, who was clearly highly interested in fashion and domestic affairs, is an excellent source of information about the domestic arrangements of the American women sculptors in Rome. Freeman, for example, moved almost annually, packing up her rooms for the summer seasons, when she would travel outside the city. In winter 1865–66, she was living with the Williams sisters. Here we learn that Lewis had a bedroom and a parlor for entertaining and was, presumably, sharing a larger, divided living space with other residents. Freeman and others in her circle rented rooms and had their meals prepared for them by Italian hosts or servants. Based on other arrangements discussed by Freeman, it is likely that the Williamses had helped organize living arrangements for Lewis, where she would rent these two rooms and be provided with board for an additional fee. ↵

- At this time, the Italian peninsula was divided into numerous separate governments. Florence was under Austrian rule, while Rome was the heart of the Papal States. To relocate from Florence to Rome, Lewis would have been required to have her passport approved, and her luggage would have gone through customs, where, apparently, it was delayed for some time. ↵

- Freeman to her family, January 7, 11–13, 1866. ↵

- Gibson took ill around January 11, 1866, and died January 27. His illness is discussed in some detail in Freeman’s letters between these dates. ↵

- Gibson had been a prominent and vocal proponent of Hosmer’s meteoric success—encouraging prominent visitors to admire her work, which he promoted alongside his own. After Gibson’s death, Freeman was only beginning to have her first models carved in marble, and she never found a prominent sculptor to advocate in a similar fashion for her work. ↵

- Hosmer’s role in the care team for Gibson and Freeman’s worry for her friend are discussed in Freeman’s letters from January 1866; see box 2, folders 114–15, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Freeman to her family, January 22, 26–27, 1866, box 2, folder 115, Freeman Letters. The “us” referred to in this letter is Freeman and the Williams sisters. ↵

- Freeman was a skilled pianist and often wrote to her mother about the songs she was playing and the musical highlights (or lowlights) of the social gatherings that she attended. She also went to numerous concerts in Florence and Rome. ↵

- Having attended and nearly completed her education at Oberlin College, Lewis would certainly have been exposed to the rules of polite society, as female education at this time included strong emphasis on these areas of comportment. ↵

- Freeman to her family, January 22, 26, 27, 1866. ↵

- Freeman to her family, February 16, 1866, box 2, folder 117, Freeman Letters. ↵

- The group were celebrating George Washington’s birthday, an annual highlight of the expatriate American community in Rome. ↵

- Freeman to her family, February 24, 28 ,1866, box 2, folder 118, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Freeman to her family, March 8, 16, 1866, box 2, folder 119, Freeman Letters. I have not yet identified these additional guests named as in attendance at Lewis’s party. ↵

- Freeman to her family, May 13, 22, 24, 27, 1866, box 2, folder 126, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Freeman to her family, March 17, 1866, box 2, folder 120, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Freeman to her family, March 24, 29, 1866, box 2, folder 121, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Freeman to her family, March 24, 29, 1866. ↵

- Buick, Child of the Fire, 14–17. ↵

- Freeman to her family, January 17, 1865, box 1, folder 83, Freeman Letters. ↵

- See esp. bk. 15, titled “Hiawatha’s Lamentation.” Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha was a contemporary and highly popular piece of literature, first published in 1855. Interestingly, Longfellow based his poem on materials collected by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft among the Ojibwe, Lewis’s own Indigenous nation. For a succinct overview of the history and context of the poem, see Woodrow W. Morris, introductory note, April 1, 1991, for the Project Gutenberg eBook of The Song of Hiawatha, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19/19-h/19-h.htm#INOTE. Although Chibiabos has not yet been found, a photograph thought to be of the work is available in the Freeman Letters. ↵

- For discussion of Lewis and the Hiawatha series, see, Buick, Child of the Fire, 77–132; Vasiliki Karahalios, “Form, Presence, and the Performative Body: Edmonia Lewis’s Hiawatha Series, 1865–1873” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 2021); and Marilyn Richardson, “Hiawatha in Rome: Edmonia Lewis and Figures from Longfellow,” Incollect, March 21, 2004, https://www.incollect.com/articles/hiawatha-in-rome-edmonia-lewis-and-figures-from-longfellow. ↵

- At this time, Freeman had a studio adjacent to Hosmer. This is particularly interesting, given that Child gives Lewis’s first access to Hosmer’s studio as occurring in April 1866. Child also quoted Hosmer as saying, “A Boston lady took me to Miss Hosmer’s studio,” possibly referencing Freeman. See Buick, Child of the Fire, 64. ↵

- Freeman to her family, June 24, 26, July 2, 1866, box 2, folder 129, Freeman Letters. Freeman was a Protestant, though she attended church infrequently. I did not locate an earlier mention of Lewis’s illness, other than the mention in March cited above, but this could be due to a lost letter or to Freeman neglecting to mention the illness to her family. ↵

- See “Isobel Cholmeley,” Royal Academy of Art, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/isabel-cholmeley; and Henderson and Henderson, Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis, bk. 2, ch. 12. I did not identify other mentions of Cholmeley in Freeman’s letters, but the two may have interacted in Gibson’s circle. ↵

- Dabakis refers to Lewis as a “lifelong” Catholic; in Sisterhood of Sculptors,167. Buick posits that Lewis may have been a “lifelong believer” in Catholicism and more broadly emphasizes the significance of Catholic work to her career; in Child of the Fire, 26–27. Henderson and Henderson discuss Lewis as a heritage Catholic and draw on a story about her conversion published by Cecilia Cleveland in The Story of a Summer (1874); in Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis, bk. 2, ch. 12. Cleveland also links Cholmeley to Lewis’s conversion, though with a garbled version of her last name (giving it as “Chomeley”). One possibility is that Lewis, whether or not she had previously followed the faith, took the step of formally joining the church in Rome by going through the confirmation ceremony. ↵

- Buick considers the intersection of politics and faith for Lewis, arguing that Lewis thought of Giuseppe Garibaldi as a hero and that Lewis was in “support of the Risorgimento”; Child of the Fire, 22–25. ↵

- Anti-Catholicism is pervasive across mid-nineteenth-century sources and is a prominent theme in the writings of American Grand Tourists about their experiences in Italy. For an in-depth consideration of anti-Catholicism as a factor in the society and politics of the United States in this period, see Tyler Andbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (Oxford University Press, 1992). ↵

- Freeman to her family, November 16, December 6, 1866, box 2, folder 139, Freeman Letters. ↵

- Gibson had a large and prominent studio that would have far exceeded Lewis’s needs and means, and it seems these reports need to be revisited, similar to the assertions that Hosmer and Cushman were Lewis’s first and best friends in Rome. ↵

- Williams Papers, https://pem.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/644. ↵

- Eunice Maria Faxon Weeks, Journal of Travels, 1862 to 1867, MSS 192, Boston Athenaeum. Of course, it is impractical for any one scholar to conduct a thorough review of all such possible sources. Rather, as modeled in this article, scholars could practice generosity and seek out platforms for sharing when they identify relevant references. ↵

- Buick, Child of the Fire, 26–27. ↵

About the Author(s): Julia A. Sienkewicz is the Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo Associate Professor of Art History at Roanoke College in Salem, Virginia.