For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability

PDF: Hudson, review of For Dear Life

Curated by: Jill Dawsey and Isabel Casso, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

Exhibition Schedule: Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, September 19, 2024–February 2, 2025

Exhibition Catalogue: Jill Dawsey and Isabel Casso, eds., For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability, exh. cat. Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, 2024. 296 pp., 116 color illus. Cloth: $45.00 (9781477331026)

In 2019 the Getty announced Art x Science x LA as a placeholder for the third installment of its sprawling art initiative PST ART (previously known as Pacific Standard Time). Although the more than sixty exhibitions ultimately funded through PST ART were intended to stage past and present intersections of art and science, the gambit arguably pointed to something differently contemporary. At the time, it was hard not to correlate this theme with the civic boosterism that had delivered to Los Angeles an innovation corridor none-too-subtly rebranded as “Silicon Beach.” Technology start-ups and more established corporations settled along the city’s west side, close to the international airport that would shuttle workers in and out of town. Entrepreneurs aggregated in a geographical cluster that recalled in structure as well as name its Bay Area prototype, and the whole experiment befitted a California economy under thrall of speculation. It is worth recalling, too, how commercial-art enterprises cozied up to engineering campuses, with Pace Gallery, for example, launching a pop-up space at a Menlo Park Tesla dealership in 2014 (and in 2016 opening a more permanent venue in nearby Palo Alto, ultimately abandoning it in 2022 in favor of a flagship location in LA).1

But when PST ART unveiled its programming in September 2024, the technology boom on which it was predicated had become historical in its own right. Many of those sand-adjacent offices remained empty as COVID-19 necessitated remote work and companies shrank their physical footprints in the pandemic’s regulation-choked aftermath. And peripatetic travel indexed anew less gratuitous agility than disregard for environmental catastrophe. Perhaps the latter goes some way to explain why a preponderance of shows in what became the art event Art & Science Collide dwelt on ecological topics, by turns plaintive and didactic, with many centering Indigenous epistemologies and methods of stewardship that might yet save us all. Still, given the regional histories to which PST ART appealed, it was remarkable how few shows took up agriculture or aerospace, the tools of the film industry or emergent Artificial Intelligence. To be sure, AI did appear to disastrous effect in the Getty-commissioned WE ARE: Explosion Event, Cai Guo-Qiang’s daytime fireworks extravaganza at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Meant to kick off PST ART with his custom AI model cAI™, Cai’s pyrotechnics resulted in charred debris and injured bystanders, a staged apocalypse inauspiciously set against the backdrop of parched hillsides burning with seasonal wildfires.2

Likewise surprising was the rarity of shows dealing with biomedical cultures—life and health sciences, genomics, and the like—which are overrepresented in Southland universities, research institutes, and biotechnology companies. Notable exceptions included a group show highlighting disability art practice, Opulent Mobility, in the Hoyt Gallery at Keck Medicine of the University of Southern California, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles’s Scientia Sexualis, which brought together artists who employ scientific discourses to propose alternate “frameworks that tell us not only what sex and gender are, but what a body is and can be.”3 Free the Land! Free the People! at the Crenshaw Dairy Mart framed capitalism and the carceral state as drivers of health-care inequality. The monographic Beatriz da Costa: (Un)disciplinary Tactics at Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery recovered the work of a citizen scientist, showing, among much else, pieces dealing with the late artist’s management of her own cancer.

Down the coast, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD) presented the ambitious For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability, comprising more than 120 works by eighty-five artists (fig. 1). It claimed precedent as the first exhibition to survey illness and impairment in American art since the 1960s—as a determining factor for American art since 1960—in the process arguing for a newfound (that is, postpandemic) awareness at scale of the vulnerability of the human body and a shared, anticipatory closeness to unhealth.

The MCASD in La Jolla is located near the mesa on which the University of California, San Diego, sits alongside the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Scripps Memorial Hospital, and plenty of industry pharmaceutical labs. Meanwhile, Tijuana, Mexico, a border city just south of San Diego, markets itself as a destination for medical tourism. In insisting on the apposition of illness and disability to aesthetics, the curators of For Dear Life, Jill Dawsey and Isabel Casso, seemed to understand the exhibition’s role in this ecology as productive of critical response to the medicalization of life, inclusive of medical models of disease. Reflexive site specificity of a kind, they also marshaled histories of regional feminisms to emphasize the inextricability of the personal and the institutional. Importantly for this revisionism, they affirmed the centrality of rights movements from the 1960s and 1970s, particularly the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement in Berkeley and, with it, the visibility of agency in bodies occupying space. (This led to a brilliant reframing of the period turn to performance as inseparable from issues of advocacy founded on endurance and coalition.) Even the show’s subtitle, “Art, Medicine, and Disability,” references curricula generated by Katherine Sherwood, an art professor who started the first art and disability studies program at the University of California, Berkeley.

The wall panel in the opening gallery flagged the “temperate climate, progressive educational institutions, and embrace of holistic forms of healing” that have drawn people to the West Coast. Nevertheless, like the team behind Free the Land! Free the People!, Dawsey and Casso called out the disproportionate impact of economic and environmental policies on minority communities, including people with disabilities. The stakes of the show, then, rested not (or not only) in pointing to histories of exclusion but more profoundly, and in line with recent theorizing as exemplified by Johanna Hedva, in arguing that disability is an open minority into which any of us can move.4 Sherwood herself experienced a cerebral hemorrhage that paralyzed the right side of her body.5 Beyond the titular homage, Sherwood surfaces in the show with two mixed-media canvases made after her stroke (fig. 2). These large-scale paintings incorporate brain scans, once diagnostic images that, now differently functional, serve as a base for the application of gestural passages. The accompanying catalogue further reminds readers that Sherwood mentored other included artists, Sunaura Taylor and Sandie (Chun-shan) Yi, fostering a constructed genealogy of intergenerational understanding.

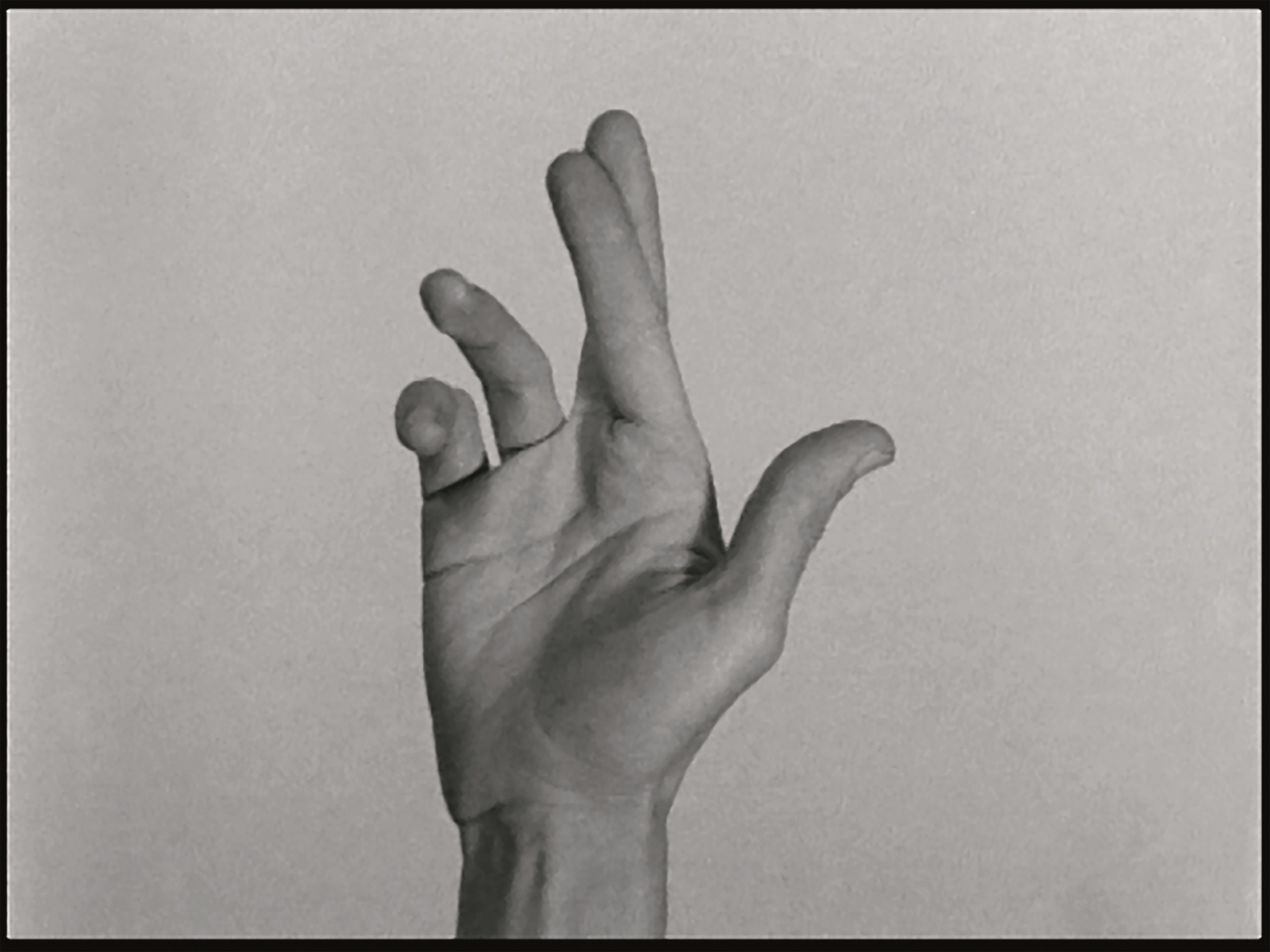

Synchronic versions of kinship similarly configured the issues that guided the exhibition and anchored its loose chronology: from the Women’s Liberation Movement to an excellent juxtaposition of the epidemics of HIV/AIDS and breast cancer; to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the fraying health-care infrastructure; to the rise of DNA testing and issues it raises regarding privacy around genetic discrimination; to the opioid crisis and Nan Goldin’s P.A.I.N. advocacy organization; and so on. Experience of illness or disability extended out from the first arrangement, where Yvonne Rainer’s eight-minute silent film, Hand Movie (1966), played high on a wall (fig. 3). Rainer made it in her hospital bed while recovering from surgery; unable to dance with the rest of her body, she was left with these digits alone as capable of expressive movement. The curators describe the piece in the wall label as an instance of “illness . . . as a generative space for art.” As such, it raises many issues, not least the connection of this and other work made in a health-care setting—like Hannah Wilke’s Sloan Kettering, Nov. 8, 1992 (1992), a delicate floral watercolor on a standard-issue hospital pillowcase—to structured modalities of occupational and art therapy.

Here and elsewhere a question became: What—if any—is the therapeutic capacity of this work, whether intended or otherwise? Subsequent galleries did not so much answer this query as raise different uncertainties. The visitor encountered other forms of compensation or prosthesis, like David Hockney relying on fax machines to communicate as his hearing waned. But more commonly the exhibition confronted the ameliorative role of art making in the face of disease. This is not to say that the art shown here does not process or share experience; it does exactly that. Yet neither is it a talisman. Wilke was not cured of her lymphoma. Tishan Hsu made his epic panel Institutional Body (1986) while waiting for technology to improve the outcomes of his needed kidney transplant (which he did not receive until 2006). It is in this invocation of waiting—or holding on, as it were, for dear life—that the show asserts most forcefully the suspension but also necessity of life during illness. The etymology of “patient” derives from the Latin verb patior, which means “to suffer or endure.” So what, then, is the role of art amid this duration?

Agitation, for one. Although emblems of political engagement appeared throughout, the last section of For Dear Life posited the goal of social action most directly through artists confronting disability justice (including Joseph Grigley, Carolyn Lazard, Riva Lehrer, and Christine Sun Kim). Park McArthur’s photograph, How to Get a Wheelchair over Sand (2013) is a sharp condemnation of the limits of accessibility, while sometime collaborator Constantine Zavitsanos’s Specific Objects (Stack) (2016) lines up grab bars mounted on the museum wall (see fig. 1) as painfully wry rejoinders to Donald Judd’s would-be autonomous Specific Objects. This cluster of affiliation tracks with recent curatorial and textual undertakings that reclaim disability and propose what Amanda Cachia, who likewise contributed a text to the accompanying catalogue, has dubbed “access aesthetics.”6 Ending with artists who openly identify as disabled heightened the contrast with those in preceding galleries who might not wish to be so identified—effectively outed in this categorization—or defined by their suffering. Not all have found solace in nonconformity, though it proves liberatory within the crip aesthetics with which the show concludes (with projects including Yi’s Crip Couture series [2011], which draws attention to rather than veils sites of bodily difference).

Not really a show about the history of disability rights, For Dear Life is not necessarily a history of anything else, either. However, its temporal bracket does yield a periodization within which the vicissitudes of health-care delivery under conditions of neoliberalism and the embodied responses to cultures of biomedicine became the subject of art, which is to say, another form of institutional critique. This periodization is additionally coincident with the shift from inpatient institutionalization to community-based mental-health centers following the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, which remains outside of its purview but might productively be considered together with it. Taken on its own terms, For Dear Life was above all an exercise of curatorial activism, enacting a position commensurate with the crip art and collectivism that it unapologetically celebrated. Having never really been defined, art, medicine, and disability were left open, maybe purposively. The cumulative effect of the works brought together under such capacious and combinatory signs was both declarative and interrogative: How does art mark the time of illness and disability, and how might art but also medicine be marked by it? To what end, and for whom?

Cite this article: Suzanne Hudson, review of For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19962.

Notes

- Alex Greenberger, “Pace Gallery Closes Palo Alto Space After ‘Consolidating’ West Coast Operations,” ARTnews, July 19, 2022, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/pace-gallery-palo-alto-closes-1234634618. ↵

- Jori Finkel, “Bizarre Optics at Cai Guo-Qiang’s Fiery Kick-off Event for Getty’s PST Art Initiative,” Art Newspaper, September 6, 2024, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/09/16/cai-guo-qiang-fireworks-getty-pst-art-launch-event. ↵

- Scientia Sexualis, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, https://www.theicala.org/en/exhibitions/137-scientia-sexualis. ↵

- See Johanna Hedva, How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom (Hillman Grad Books, 2024). ↵

- ArtForum video, “Jill Dawsey on ‘For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability’ at MCASD,” ArtForum, January 24, 2025, https://www.artforum.com/video/jill-dawsey-on-for-dear-life-art-medicine-and-disability-at-mcasd-san-diego-1234725956. ↵

- Amanda Cachia, The Agency of Access: Contemporary Disability Art and Institutional Critique (Temple University Press, 2024). ↵

About the Author(s): Suzanne Hudson is professor of art history and fine arts at the University of Southern California.