The 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders’ Mugshots: A Visual Intervention

A small, unremarkable image appeared at the bottom right corner of the May 26, 1961 issue of the Jackson, Mississippi, daily newspaper, the Clarion Ledger. In the photograph, a White baby sports sunglasses and a white bonnet, propping up a book titled How to Retire Young between his chubby fingers (1961, AP Wirephoto). It is the kind of image that would elicit a noncommittal chuckle if, in fact, the caption was not a telling example of Mississippi’s long-standing resistance to integration and the casual ways in which this sentiment permeated visual culture. A pendant to the headline “Racial Scene is Quiet Once More in Jackson,” the caption reads “Tired of ‘riders’ and their pictures? How’s this one for relief?”1 The riders in question were participants in the 1961 Freedom Rides, a summer demonstration organized by CORE, the Congress for Racial Equality, to test the Interstate Commerce Act; the more recent 1960 Supreme Court decision, Boynton v. Virginia; and the recently elected John F. Kennedy, who had made promises to protect every American’s constitutional rights.2

In 1961, CORE recruited interracial activists, clergymen, and college students to integrate bus and train stations throughout the South. Departing from Washington, DC, on May 4, the group encountered hostility as they traveled south. Outside of Anniston, Alabama, White mobs chased down and firebombed the Freedom Riders’ bus, barricading the doors in an attempt to trap them inside and severely injuring several demonstrators. This followed brutal attacks in Birmingham and Montgomery, all of which were overlooked, if not encouraged, by law enforcement.3 Photographs of the bombing and mob violence comprise some of the most well-known visual records of the 1961 Freedom Rides: White mobs attacking riders in the cramped hallway of a bus station, riders fleeing a burning Greyhound, the charred skeleton of the bus, empty and foreboding, on the side of the road, and riders sprawled out on the grass in a state of shock. The circulation of these violent images sparked public outcry, prompting the staunchly segregationist Mississippi governor, Ross Barnett, to make an agreement with United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy. When the riders continued to Jackson, Mississippi, they would be arrested for “breach of the peace” upon exiting the bus, curtailing mob violence, and avoiding the media fallout that had thrown Alabama into the spotlight.4

The Clarion Ledger followed suit. After the first arrests in Jackson, the newspaper minimized the riders’ visual presence and lauded the Jackson Police Department efforts to maintain order. For a newspaper that claimed its readership was in need of relief from the sensationalized photographs capturing the Freedom Riders’ progress, the Clarion Ledger had published remarkably few—and remarkably de-sensationalized—images of the Freedom Riders’ journey. While the newspaper devoted hundreds of words to the riders’ progress in the weeks leading up to their arrival in Jackson, the pictures to which the caption of the Ellis photograph refers were largely absent. In fact, not a single image of an identifiable rider was published in the paper until May 21, 1961, when the front page featured a closely cropped, highly publicized image of the White activist Jim Zwerg, who was severely beaten in Montgomery (1961, AP Wirephoto).5 On the sixteenth page of the same issue, amid Woolworth advertisements for muumuus and 4-H club announcements, the editors also included an image of three White men in the act of attacking a Black Freedom Rider (1961, AP Wirephoto).6 The Clarion Ledger resorted to more pointed and damaging tactics in articles that fashioned the riders as outsiders at best, and un-American at worst. For example, they published the names and “crimes” of the riders who had been arrested prior to the Jackson demonstrations.7 In his “Affairs of State” column, Charles Hills made a concerted effort to maintain that local Black people reacted unfavorably toward the Freedom Riders.8

Images of the Freedom Riders’ arrival in Jackson, published in the May 25 issue of the Clarion Ledger, reflect the state campaign to quell a media frenzy and silence the purpose of the action. In one photograph taken that day (fig. 1), a crowd of photographers encircle a police wagon on one side as police officers create a barrier on the other. A Freedom Rider climbs inside, as others follow behind single file and seemingly without assistance. The street is cleared, and onlookers mingle on the sidewalk across the street. Despite the order the photograph captures, and the Mississippi government’s and White media’s consistency in downplaying the Freedom Riders’ demonstration, a trace of noticeable violence remains: the strips of bandages atop a rider’s head, who crouches as he steps into the back of the truck. The photograph captures the riders’ backs, eliminating their individual characteristics, movements, and expressions. Compared with a widely circulated photograph of an enraged White mob beating a demonstrator in Birmingham (fig. 2), the images of the Freedom Riders’ arrests in Jackson do not reference the violence that would take place once the riders were “safely” out of view of the journalists’ flashing cameras. White Mississippi orchestrated a partial media blackout. Nothing to see here.

CORE and the Freedom Riders adapted to this strategy, shifting their focus from a media campaign to filling the Mississippi jails. As organizer James Farmer stated, their new goal was to “Mak[e] segregationist practices so expensive as to become infeasible.”9 By the end of the summer, over three hundred students, clergymen, and activists, both Black and White, circulated through the Mississippi prison system. By June 15, 1961, Barnett relocated the riders to the notoriously brutal Parchman State Penitentiary, where they were placed on the prison’s maximum security unit.10 Behind closed doors, the prisoners were tortured with electric cattle prods and wrist breakers, burned with cigarettes, sprayed with fire hoses, and then blasted with industrial-sized fans for up to twenty-four hours at a time.11 While protesters were exposed to extreme danger and violence during their demonstrations, their visibility, and the rapid circulation of images most protests relied on, offered a fragile semblance of protection. Behind the doors of Parchman, however, the violence was allowed to go totally unchecked.

Every Freedom Rider that came through the Jackson Greyhound Station had their mugshot taken, and every mugshot—more than three hundred by the end of the summer—was catalogued in the offices of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (MSSC).12 In operation from 1956 until 1977, the MSSC was created to, “do and perform any and all acts deemed necessary and proper to protect the sovereignty of the State of Mississippi . . . [from] encroachment thereon by the Federal government or any branch, department, or agency.”13 In other words, the Sovereignty Commission maintained segregation by tactics of surveillance, propaganda, intimidation, and violence throughout its existence. In 1977, the organization was officially disbanded. Debates about whether or not to destroy the archives began, an act which would have eliminated a paper trail of complicity in wiretapping and assisting country registrars in keeping Black citizens from registering to vote.14 It was agreed that the Mississippi Department of Archives and History would seal the files until 2027; however, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit against the state, claiming the illegal surveillance of its citizens, and won, making the archives public in 1998.15

That the Sovereignty Commission endeavored to erase the Freedom Riders’ presence in Mississippi is felt in the MSSC archive, particularly through the mugshots: enigmatic and powerful images that comprise the overwhelming majority of visual representation of the Freedom Rides in Mississippi. On a material and contextual level, the mugshots operate within a difficult and loaded visual arena. The simultaneous development and proliferation of the photographic portrait, a consensual form of representation, put the mugshot, its counterpart, into relief, giving greater visibility to the supposed differences between those regarded as law abiding citizens and those considered criminal.16 While photographic processes changed dramatically from the introduction of the mugshot in the United States in 1895, the formal constraints of classification did not. Six decades prior to the Freedom Rides, Major Robert Wilson McClaughry edited instructions for how to take a proper juridical photograph, penned by the inventor of the mugshot, Alphonse Bertillon:

Take care that in both poses, the full-face and profile, the subject is squarely seated, his shoulders as much as possible at an even height. . . . The subject should be caused to fix his eyes steadily on the camera. . . . In the profile pose, one can avoid the very frequent displacement of the eye sideways in the direction of the operator by asking the subject to look at some fixed point or, still better, at a mirror.17

While the mugshot is inextricably linked to state surveillance, there is potential in reading beyond its constraints of systemization and criminalization.

As Ariella Azoulay argues in Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography, photography represents a moment of encounter between subject and photographer, a set of unfixed relationships into which contemporary viewers can intervene. Azoulay calls this the “event of photography” in which photography “may even contradict the intentions of any of the original players engaged in the event at the moment of its unfolding, cataloguing, undermining and reifying the power dynamics between photographer, subject, and viewer.18 When the investigator or police officer photographed each Freedom Rider, they were certainly in physical control of the moment of encounter. The MSSC controlled the conventions of the mugshots as well as their storage and use. Nevertheless, contemporary views can unravel this power dynamic in favor of one in which the sitter weakens the original photographic purpose.

Despite their origins, however, they seem to exist outside of both Mississippi’s whitewashed, banal representation of the Freedom Rides and the violent photographs of protest that theorist Martin A. Berger calls “iconic.” Both types of imaginaries—banal or violent—fostered a visual framework that appealed to White audiences. As Berger acknowledges in his book Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography, widely circulated images of the Civil Rights movement were not “staged or doctored to meet the needs of Whites.” However, he also contends that “the handful of ‘iconic’ photographs endlessly reproduced in the newspapers and magazines of the period, and in the history books that followed, were selected from among the era’s hundreds of thousands of images for a reason: they stuck to a restricted menu of narratives that performed reassuring symbolic work.”19 Berger argues that such photographs simultaneously inspired Northern White viewers to demand Civil Rights reform and recreated “nonthreatening” power dynamics in which Whites enact violence against Black victims.20 The White Southern representation of the Civil Rights movement, at least in Mississippi, erased White Southern responsibility, placing blame on and criminalizing protesters.

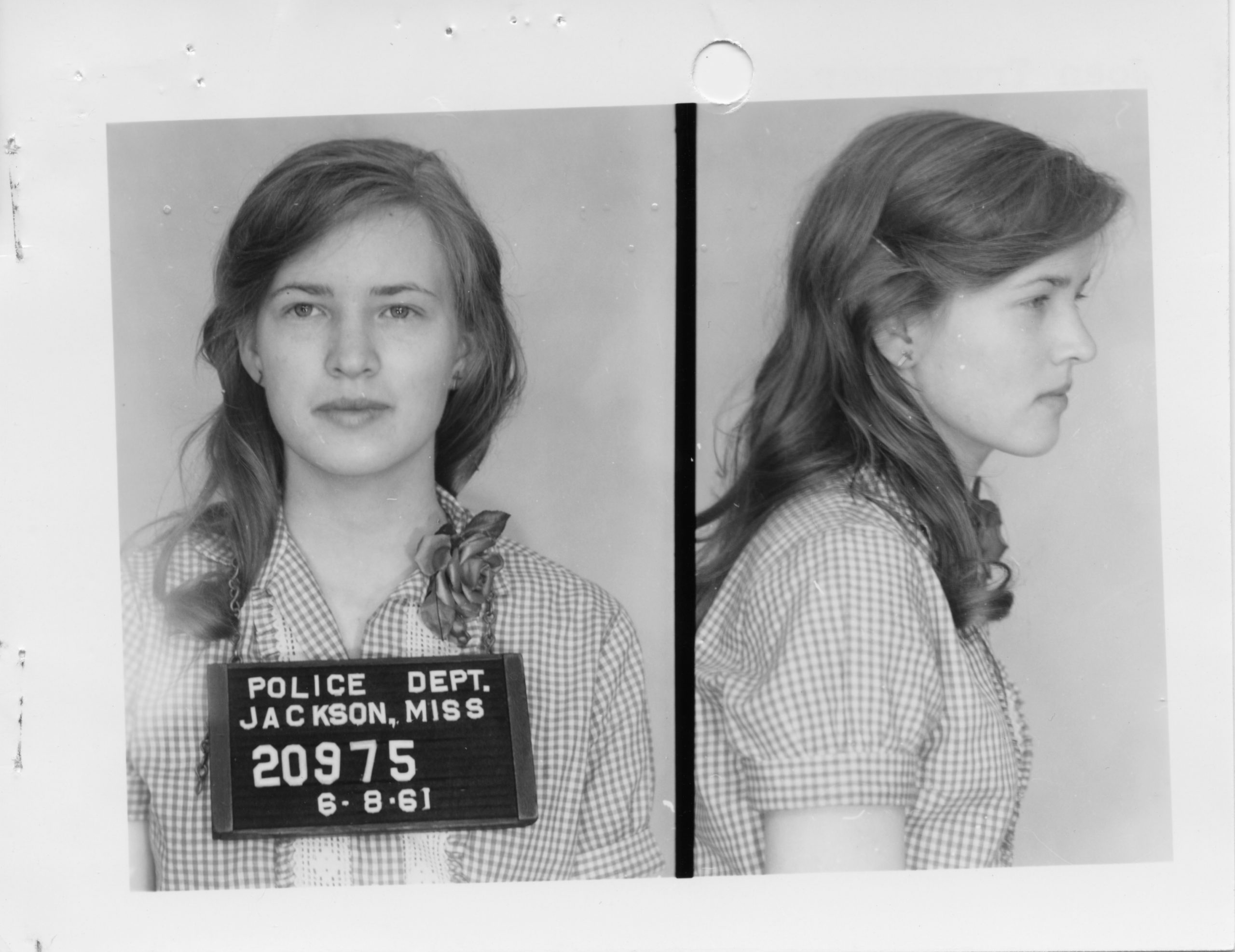

The mugshots that were in MSSC possession confirmed the subjects’ criminality to those who would have viewed them. The photographs, which remained in a state of arrest until their release in 1998, are worn from frequent handling in the investigative process, a point that perhaps instantiates claims that the continued observation of these mugshots confirmed the portrayal by the MSSC of the riders (and later activists) as criminal. For example, activist Joan Trumpauer-Mulholland’s mugshot (fig. 3) is riddled with holes, perhaps where it was thumbtacked to a wall or stapled to a dossier. Her file, to which her image was likely affixed, contained information about her personal life, articles in which she was mentioned, and correspondences that might indicate that the MSSC had tapped her telephone conversations.21 The relationship of these photographs to viewers changes over time, from documents of criminality in the eyes of MSSC members to records of participation in a non-violent protest in the present day. The visual traces of resistance embodied in the Freedom Riders’ mugshots perhaps forge openings for understanding the mugshots as potentially existing outside of the constraints of their creation.

Indeed, other historians and contemporary viewers have considered the mugshots in this light. They were the subject of Breach of the Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders, a 2011 monograph by Eric Etheridge and accompanying exhibition presented at the Mississippi Museum of Art, and they are currently reproduced in a gallery in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, entitled “A Tremor in the Iceberg.” That these photographs would be characterized as portraits rather than mugshots indicates that these images are now interpreted as embodying individual agency in some form or fashion. In fact, a number of surviving, consenting veterans of the demonstration were photographed fifty years later in formal portraits, which are exhibited nearby with their mugshots.

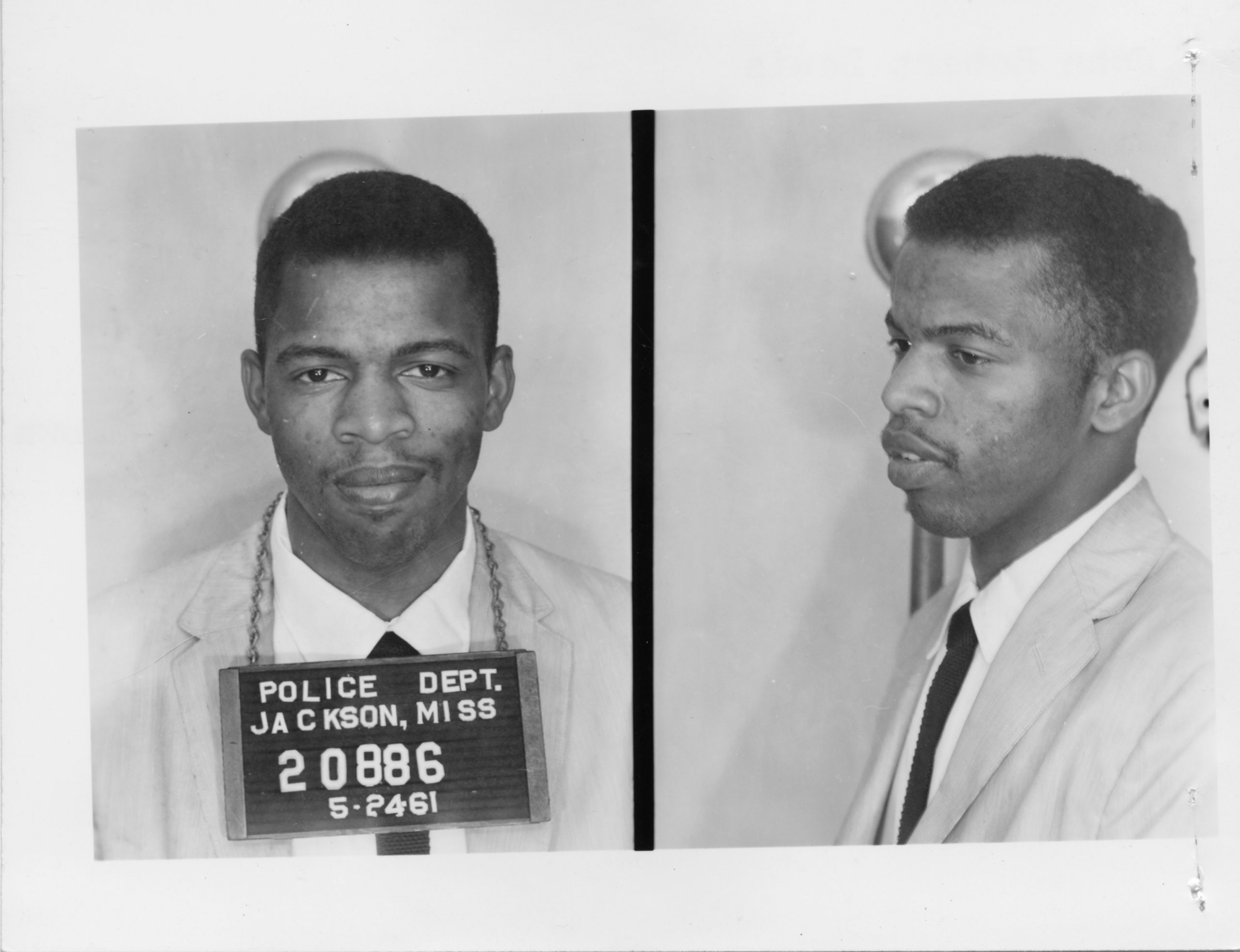

Former Congressman John Lewis’s mugshot (fig. 4) is among the most widely circulated and recognizable of the Mississippi Freedom Rider images. In it, he appears prepared, wearing a sturdy coat in the middle of summer and a close-lipped smile. He does not resist being photographed, and his image—frontal, evenly lit, cropped—adheres to the conventions of the mugshot. His expression is resolutely opaque, if not revealing a slight smirk. Poet and theorist Fred Moten might describe this expression as elsewhere, a state of being he observes in a famous photograph of Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Little Rock Nine, as she walks to school, a mob of White women following closely behind:

Perhaps this is because Eckford’s eyes are obscured by shadow and by her sunglasses . . . perhaps this is because her eyes are hidden—in plain sight . . . in having something or somewhere else infused in them. Not against, not substituting for the brutal time and place of her seeing, of her being unseen in being seen, Eckford appears, to those who want to feel, to place her eyes and thoughts elsewhere. Elsewhere, which is the nature of her (refusal of) time and place, is in her eyes as she strides, strives, in and toward earth in and out of the world . . . in and as (a black woman’s) nonperformance, which bears the story, the ongoing history, of an already existing alternative.22

What Moten sees in the image of Eckford is an unavailability toward those who would not—cannot—see: those who would bind her to the parameters of the image. It is violence and the White women in the photograph whose hatred radiates outward. For Moten, Eckford’s look elsewhere, hidden behind dark sunglasses, is what allows her to be seen. In this reading, the photograph shares many affinities with the Freedom Riders’ mugshots. Both types of images tend to flatten their subject; while the mugshots present a vocabulary of criminality, the photograph of Elizabeth Eckford has all of the trappings of reinforcing a narrative in which Whites are the active agents. However, we might find elsewhere in these vastly different photographic enterprises, collapsing real time with our present engagement. Lewis undoes the visible and invisible power dynamics that are at stake in his likeness through the mere fact that he is a political prisoner and practicing nonviolence. While the latter is represented by his visible compliance in the image itself, his resistance is also visually signaled by his preparation for arrest.

Lewis’s khaki coat is one such aspect of his resistance. Demonstrators were instructed to wear clothes that would best protect their bodies, both during demonstrations, which often turned violent, and while in jail. In A Manual for Direct Action, George Lakey and Martin Oppenheimer instruct protesters who face arrest to:

Wear decent, tough, clothing, but not your best. If you expect to be jailed, wear two sets of underclothes so that you can wear one set while washing the other. This is also helpful padding if you are dragged about by police. An extra pair of socks also helps. Wear a sweater or trench coat—cells get cold, and the coat will help cover your legs or serve as a pillow.23

Lewis’s mugshot is illustrative of Oppenheimer and Lakey’s strategy for self-protection, indicating that he was prepared for his arrest and mistreatment. Furthermore, he also exhibits a powerful affect, as do the subjects of hundreds of other mugshots from this specific protest. In spite of this, the image still captures an inequitable power dynamic between the Freedom Riders and the state, complicating the notion that the mugshots can truly evince political or individual agency on the part of their subjects.

Tina Campt, in Listening to Images, establishes an apt framework for interpreting identificatory photographs, particularly those that depict non-White subjects. She asks:

What might be gained by uncoupling the notion of self-fashioning from the concept of agency? What if we understand it as a tense response that is not always intentional or liberatory but often constituted by miniscule or even future attempts to exploit extremely limited possibilities for self-expression and futurity . . . a temporality that both embraces and exceeds their present circumstances—a practice of living the future they want to see, now?24

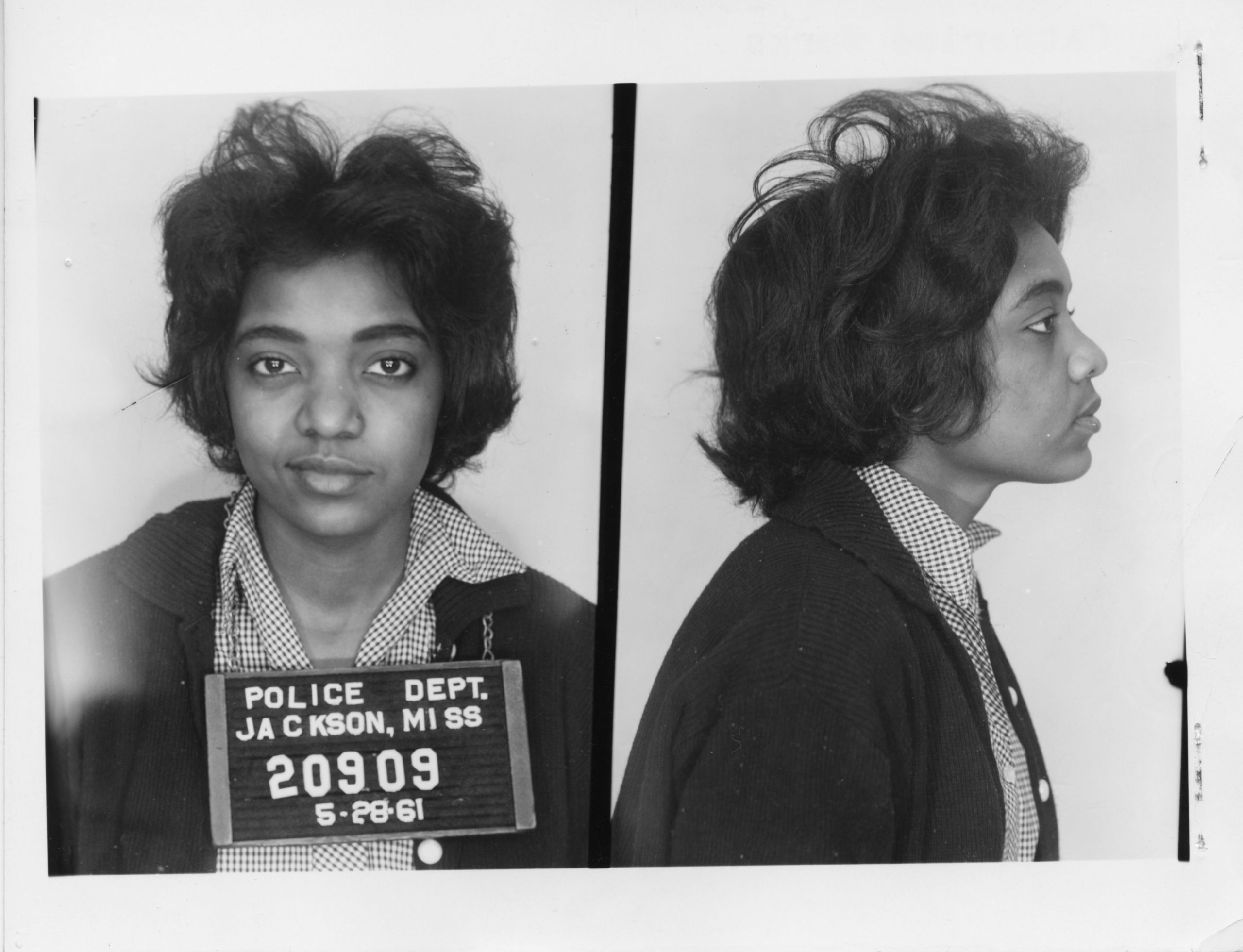

Take, for example, Catherine Burks-Brooks’s mugshot (fig. 5). She half-smiles at the camera. Her eyes have an unexpected lightness, as if she were in on a joke, which we as viewers in the position of the photographer will never know. It is possible to see an act of resilience in the photographic moment, despite the formal conditions of the image. Or at least this is what we want to see, given our removed status as contemporaries in the face of a historic archive.

The Freedom Rides were the first protests in Mississippi that changed the direction of the Civil Rights movement in the state; the sitters of these photographs knew it. The something else we see is the future, the “temporality that both embraces and exceeds their present circumstances—a practice of living the future they want to see, now.”25 We cannot locate the subject of Catherine Burks-Brooks’s gaze in her profile image. What if she sees herself in a mirror, as mugshot protocol would follow? And there, what if she finds in herself an alternative condition to the one she faces? In following this directive, the photograph of Burks-Brooks enacts a phenomenon shared by many of the mugshots—a futurity that exists beyond the moment of its execution. By proposing such interpretations, we can complicate and add to the discourse regarding these mugshots and Civil Rights photography at large.

Cite this article: Johnna Margot Henry, “The 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders’ Mugshots: A Visual Intervention,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9879.

PDF: Henry, 1961 Freedom Riders Mugshots

Notes

- Associated Press Wirephoto, “Tired of ‘Riders?’” Clarion Ledger (Jackson, MS), May 26, 1961, https://www.newspapers.com/image/180068862. ↵

- Stokely Carmichael and Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (New York: Scribner, 2003), 178–79. ↵

- Carmichael and Thelwell, Ready for Revolution, 184. ↵

- John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1995), 92–95. ↵

- Associated Press Wirephoto. Freedom Rider Beaten, May 21, 1961, Clarion Ledger (Jackson, MS), https://www.newspapers.com/image/180064934. ↵

- Associated Press Wirephoto, Negro Student Attacked, May 21, 1961, Clarion Ledger (Jackson, MS), https://www.newspapers.com/image/180065256. ↵

- “‘Riders’ Here Have Past Police Records,” May 25, 1961, Clarion Ledger (Jackson, MS), https://www.newspapers.com/image/180068430. ↵

- Charles Hills, “Affairs of State,” Clarion Ledger (Jackson, MS), May 26, 1961, https://www.newspapers.com/image/180069018. ↵

- James Farmer, Freedom—When? (New York: Random House, 1965), 70. ↵

- Carmichael and Thelwell, Ready for Revolution, 198. ↵

- Carmichael and Thelwell, Ready for Revolution, 203. ↵

- The majority of the MSSC archives, including all of the mugshots from the 1961 Freedom Rides, are available online at http://www.mdah.ms.gov/arrec/digital_archives/sovcom. ↵

- “Agency History,” Sovereignty Commission Online, accessed October 14, 2017, http://www.mdah.ms.gov/arrec/digital_archives/sovcom/scagencycasehistory.php. ↵

- “Agency History.” ↵

- “Agency History.” ↵

- For more information on the simultaneous development of the photographic portrait and the mugshot, see Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 3–64. ↵

- In the 1880s, Alphonse Bertillon invented many techniques for identifying criminals, including standardizing the mugshot, during his time as a clerk and then the head of the Department of Judicial Identity of the Paris Prefecture Police; prior to his intervention, criminals were photographed as early as the 1840s, though without the same attention to anthropometric details. Bertillon’s system was originally published in French in 1890. For more information, see Alphonse Bertillon, Signaletic Instructions Including the Theory and Practice of Anthropometrical Identification, ed. Robert Wilson McClaughry (Cambridge: Werner Company, 1896), 241. ↵

- Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography, trans. Louise Bethlehem (New York: Verso, 2012), 54. ↵

- Martin A. Berger, Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 6. ↵

- Berger, Seeing Through Race, 8. ↵

- See SCR ID # 2-55-3-78-2-1-1, SCR ID # 1-73-0-14-1-1-1, and SCR ID # 99-143-0-4-3-1-1 at Sovereignty Commission Online, http://www.mdah.ms.gov/arrec/digital_archives/sovcom. ↵

- Fred Moten, The Universal Machine (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 76. ↵

- Martin Oppenheimer and George Lakey, A Manual for Direct Action: Strategy and Tactics for Civil Rights and All Other Nonviolent Protest Movements (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1965), 109. ↵

- Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 59. ↵

- Campt, Listening to Images, 59. ↵

About the Author(s): Johnna Margot Henry is an Independent Researcher