Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment

Wendy Bellion

Wendy Bellion

University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019; 272 pp.; 11 color illus., 51 b/w illus. Hardcover: $124.95 (ISBN: 9780271083643)

How do we write histories for works of art that no longer exist? By revealing how an empty pedestal can be full of meaning and how destruction might grow into an act of creation, Wendy Bellion’s new book offers answers to this quandary and forges fresh directions in American art scholarship along the way. Bringing together the longstanding interest in materiality and circulation within the field with more recent advances in the studies of iconoclasm and the afterlives of art, Bellion argues that over the course of the two-and-a-half-century history of the United States, iconoclasm has become inscribed within its creation story. Such is, she says, the “generative nature of iconoclasm” with its “capacity to beget new forms and to shape cultures long after the instance of destruction” (110). Framing iconoclasm in New York as a cultural impulse inherited from British traditions, Bellion further argues that iconoclasm was both “a destructive phenomenon through which Americans enacted their independence and a creative phenomenon through which they continued to exhibit English cultural identity” from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries (4).

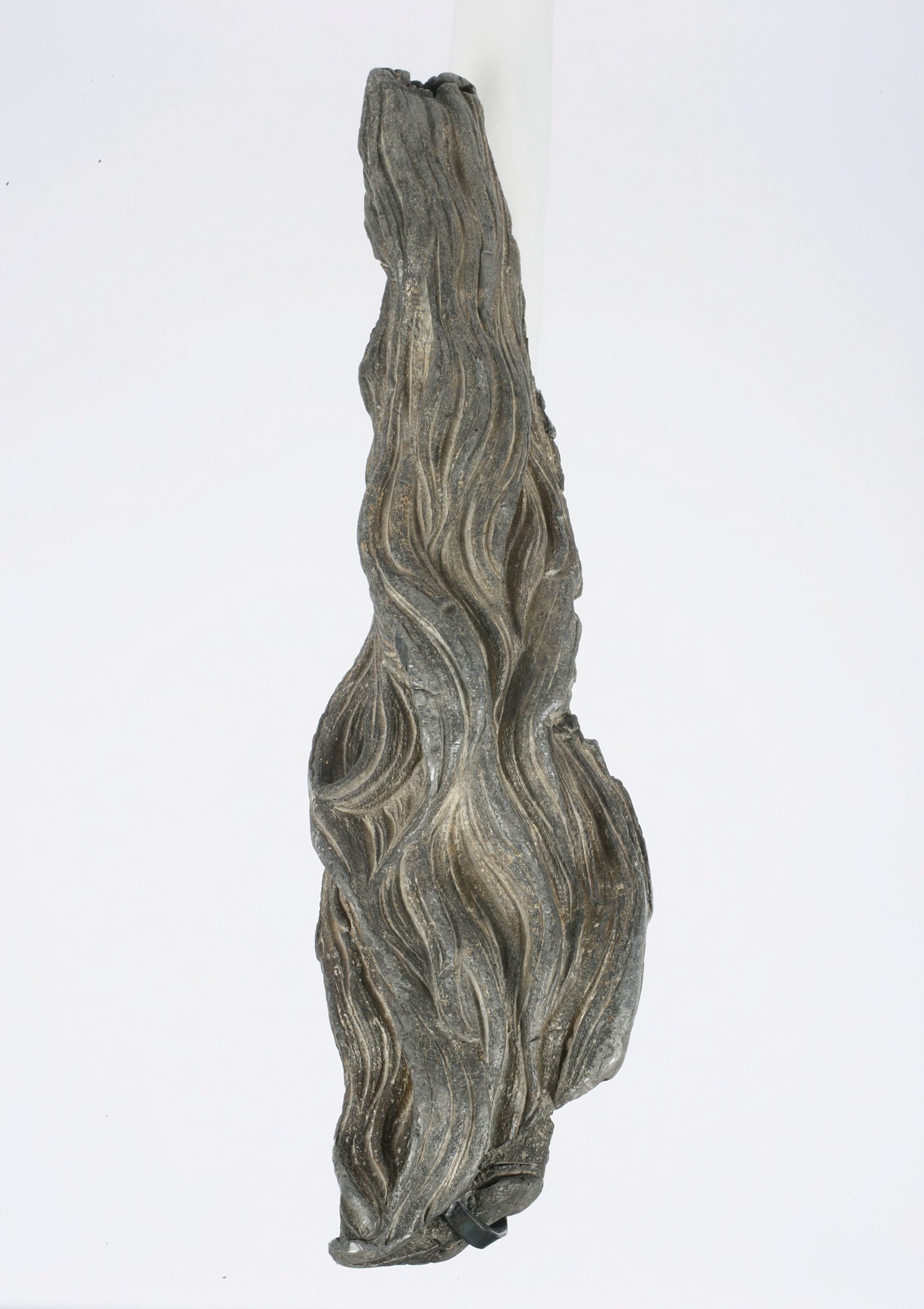

Over four chronological chapters divided into two equal parts—“Iconoclasm: The Eighteenth Century” followed by “Afterlife: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries”—the majority of Bellion’s study circles around Joseph Wilton’s (1722–1803) gilded lead statue of King George III. Bellion leads us from its creation in London to its destruction by a crowd assembled on New York’s Bowling Green following a reading of the Declaration of Independence there in 1776. We learn of the beheading and dismemberment of the statue, of its transformation into bullets made for the revolutionary cause, of the loyalist burial of its surviving fragments in swamps and ponds and under floors, and of their rediscovery over a century later. But, as Bellion cogently demonstrates, despite—or perhaps because of—the destruction of the statue, the act of violent iconoclasm against the sculpture lived on in the nation’s collective memory. It is in this way that Bellion’s text greatly advances the study of public statuary in the United States, supplementing a field that has long been based in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The author’s contribution to the study of eighteenth-century American sculpture is, however, notable for its absent center: it is an examination of a group of sculptures that are either no longer extant or survive only in fragments (fig. 1).

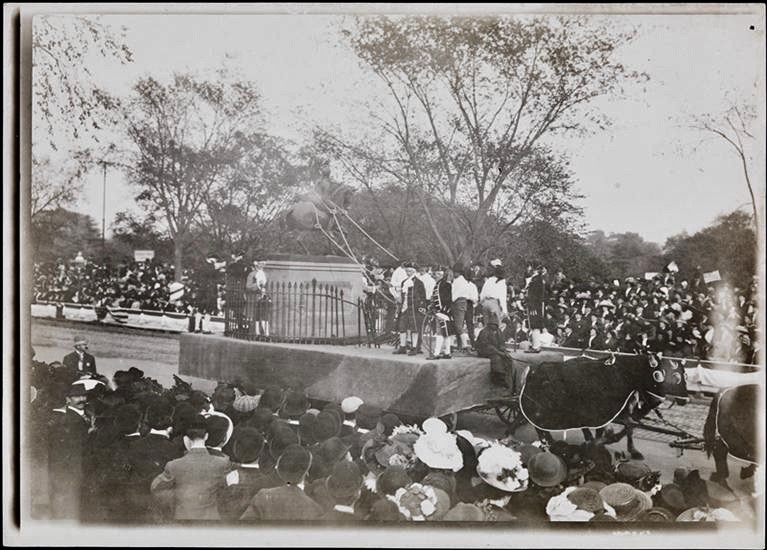

Bellion’s greatest contribution is, perhaps, in illustrating moments across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when the iconoclastic event of 1776 erupted into these later times. She demonstrates how, during the nineteenth century, the statue of the king was revivified in visual recreations by artists and illustrators; and how, during the twentieth, it was recalled by the performative parade floats of historical reenactors high on the fervor of the Colonial Revival in 1909. In this way, Bellion’s work is a model of close engagement with the specifics of an object’s situation in time and space as understood by period viewers.1 Her explorations are further mobilized by a group of working terms she advances throughout her text: reinscription, ritual, place, substitution, performance. Bellion cites a panoply of archival resources—from political cartoons to guidebooks and school primers—to provide rich detail for her theoretical framework, one built upon writings by Jane Bennett, Arjun Appadurai, and Bruno Latour.2 Analyzing the agency of public statuary within social discourse of the United States, Bellion’s work reflects the rise of “thing theory” in the humanities and social sciences and the corresponding “material turn” in the discipline of art history.3 Although this theoretical lens is now well-trodden territory, the evidence Bellion accumulates in Iconoclasm in New York offers new insights, especially into the recurring nature of iconoclasm within the American psyche and its broader significance for the nation’s social history.4

Bellion’s study begins with an account of the five liberty poles erected in New York by the Sons of Liberty and subsequently toppled by the British army between 1766 and 1776. She shows how ship masts, initially existing as found objects, were transformed by the rituals of display and ornament into “liberty poles,” which were, effectively, monumental political performances: objects accruing symbolic value as they were paraded through the city’s streets, erected on the Commons, and decorated. Loyalists critiqued these poles as “idols” and positioned the Whig belief in their animate vitality as “idolatry” (51). By using claims of idolatry as a mechanism of separation, Bellion claims, the Loyalists further distinguished themselves from Whig patriots whose animistic fetishes were lumped together with the Native Americans’ worship of pillar-like forms. Much of this material by Bellion has been previously published, but nonetheless readers of her new book will find an account significantly expanded by further evidence and fresh perspectives.5 In a particularly powerful passage, for example, Bellion takes great care to imagine what enslaved African viewers of Yoruba and Kongo descent may have recognized in the function and form of the liberty poles (42–43). In doing so, Bellion productively connects the violence of slavery with the violence of iconoclasm and demonstrates the “painful irony” of the “contradictions that structured everyday life and racial hegemonies in colonial Manhattan” (44). Such passages demonstrate Bellion’s careful speculations about marginalized perspectives throughout her text.

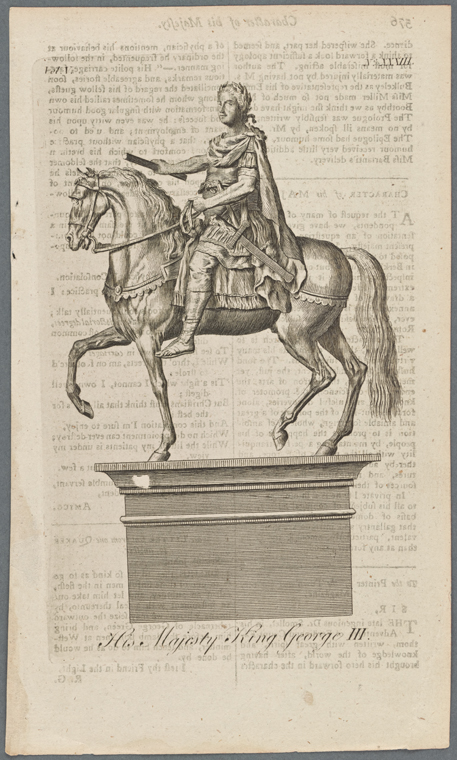

Bellion’s second chapter pivots from liberty poles to more traditional media: a gilded lead equestrian statue of King George III in the guise of a Roman Emperor, modeled after Marcus Aurelius (fig. 2), and a carved marble sculpture of William Pitt, prime minister of Great Britain, who became famous for his defense of colonists’ rights (fig. 3). Both sculptures were made by Joseph Wilton. The chapter is awkwardly divided into two sections, a division intended to emphasize the transatlantic nature of eighteenth-century art making and reception. The first section focuses on the production of the sculptures in London; the second on their installation in New York. Retelling the familiar tale of the July 9, 1776, razing of the King George statue, Bellion argues that the destruction of such monuments did not “decisively end the nation’s bond with Britain,” but rather “revealed the strength of that tie,” because colonials’ actions effectively modeled British cultural practices (106). This is, she says, “the Britishness of colonial American iconoclasm” (104). Such nationalistic arguments are less compelling than Bellion’s linkages between iconoclasm and idolatry, in which she identifies iconoclasm as a symptom of the period’s widespread “cultural disposition to credit inanimate things with the potency of animation” (102). The author cogently presents evidence of this phenomenon, so much so that the somewhat underdeveloped sections on sonic recreation (in which the author attempts to reenact the aural experience of iconoclasm in colonial New York) feel unnecessary.

The third chapter moves into the nineteenth century, following the remains of Wilton’s sculptures as they were melted down or buried (in the case of King George), used temporarily as columns (in the case of Pitt), and moved into private and public collections. This poetic and moving chapter is the volume’s best. Its primary subject matter is the sculptural fragment—aesthetically unappealing remains that appear strange, even mutant (figs. 1, 3). But what Bellion is concerned with here are not the artisanal epistemologies that have recently been the focus of many eighteenth-century art historians, but instead the fraught status of works of art that remain only in broken and politically shunted remnants.6 An evocative section titled, simply, “The Pedestal” focuses on the empty marble plinth that had previously exhibited King George’s equestrian statue. The pedestal remained at its original site on Bowling Green until 1818. In this fascinating passage, Bellion demonstrates how its vacancy was semiotically reinvented to become, over time, a monument to the revolutionary cause. But such processes of narrative-building did not end there. Bellion shows how the pillar’s emptiness was viewed by New Yorkers as a void, an echoing hollow that provoked local desire to fill it with a statue of George Washington, therefore signaling the governmental progression from one George to another. But the substitution of George Washington for King George, Bellion argues, was never fully successful, for “the reiterative agency of iconoclasm” itself reveals “the discontents of substitution, the ways in which a surrogate form problematically carries forth the lost original it is meant to replace” (128). Ultimately, the phantasmal recurrence of King George’s image within the visual culture of nineteenth- and twentieth-century America and within the figure of George Washington is evidence of “the incompletion of the revolutionary project” (132).

Bellion’s fourth and final chapter examines the pictorial resurgence of the fall of George III, an iconography invented by the Bavarian-born painter Johannes Adam Simon Oertel (1823–1909). In line with recent scholarly interventions that break down myths of American nativism and insularity, Bellion examines Oertel’s motivations for painting Pulling Down the Statue of George III, New York City in 1852 (fig. 4). She shows us a man preoccupied with revolutionary movements in his home country (the author invokes both Karl Marx and Lajos Kossuth), an artist who looked to the revolutionary history of New York City to make sense of his present. By tracing the morphing iconography of Oertel’s original image across eight sequential print reproductions of the painting, Bellion links the successive omission of women and people of color from the composition to period anxieties. For example, in prints produced during the wake of the American Civil War, images of a Native American chief, women, children, and African American figures were replaced with an all-white, all-male cast in images offering “an ideal of male brotherhood for a nation wrecked by sectional differences” (155). Bellion ties these instances of pictorial mutation to the Colonial Revival’s recoiling defenses of Anglo-American identities before identifying one final stop for the afterlife of King George III: reenactment. A parade float made for New York’s 1909 Hudson-Fulton celebration (fig. 5) brought Oertel’s two-dimensional picture into the round. Bellion argues that the tableau imagery represented “an icon of British authority” that remained “insistently present on the streets of New York” (166), again reinforcing her argument for the incompleteness of the “revolutionary project.”

Bellion’s text proves an enormous contribution to the methodology and interpretive strategies made possible by afterlives studies. Her understanding of the continued impact of works of art in social spaces and on historical memory has wide-ranging applicability throughout the humanities. But her argument could be strengthened by including a discussion of the relationship between iconoclasm as a feature of British heritage versus as a feature of British identity. For example, I hesitate to accept the reading of the George III monument, always shown in the midst of being pulled to the ground, as evidence of lingering “Britishness.” While the United States indisputably remains a cultural colony of Great Britain, I do not think we should so easily equate the depiction of a historical act of resistance as a lasting “icon of British authority.” Despite these inequivalences, however, Bellion’s volume presents a triumphant endorsement of the power of objects to act upon the human imagination.

Cite this article: Caroline Culp, review of Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment, by Wendy Bellion, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9977.

PDF: Culp, review of Iconoclasm in New York

Notes

- See also Wendy Bellion, Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2011). ↵

- See Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Arjun Appadurai, “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 3–63; and Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). ↵

- For a brief summation of this turn in American art scholarship, see Jennifer Roberts, “Things: Material Turn, Transnational Turn,” American Art 31, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 64–69. Keith Moxey offers an excellent extended discussion of the developing understanding of object-based agency in art history in his book, Visual Time: The Image in History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jennifer Van Horn utilizes a nearly identical theoretical matrix in her recent book, The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2017). ↵

- See Wendy Bellion, “Mast Trees, Liberty Poles, and the Politics of Scale in Late Colonial New York,” in Scale, ed. Jennifer L. Roberts, Terra Foundation Essays, vol. 2 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press for Terra Foundation for American Art, 2016): 218–49. ↵

- Two notable instances in American art scholarship include Jennifer Roberts, Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); and Susan Rather, The American School: Artists and Status in the Late Colonial and Early National Era (New Haven: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2016). See also Matthew C. Hunter, Painting with Fire: Sir Joshua Reynolds, Photography, and the Temporally Evolving Chemical Object (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019). ↵

About the Author(s): Caroline Culp is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University