Roaming in the South: Devin Lunsford’s Photographs from the Roadside

Born in Boise, Idaho, and raised outside of St. Louis, Missouri, Devin Lunsford (b. 1987) is a photographer who—as of 2020—is based in Birmingham, Alabama. His photographic series, All the Place You’ve Got, documents the changing landscape along Corridor X (since 2012 also known as Interstate Highway 22), that connects Birmingham to Memphis through a once remote part of northwestern Alabama.1 Roaming through this area of Alabama and taking photographs from the roadside, his work communicates the importance of place, memory, and community in the American South. Whether verdant, uninhabited spaces or the roadside signs, parking lots, and stray smokestacks that imply the presence of industrialization and human intervention, the landscape of Lunsford’s photographs suggests an aura of melancholy, loneliness, and emptiness. They participate in the visualization of the Southern Gothic.2

It is important to situate Lunsford’s work within the long tradition of photographing the American South, and specifically those who did so from the roadside. Although Lunsford hesitates to identify himself as Southerner in the traditional sense, he lives in the South, makes work in the South, and admires many Southern artists, such as William Eggleston and Sally Mann.3 Lunsford was directly influenced by a number of Southern photographers through his experiences curating the exhibition Inherited Scars: A Meditation on the Southern Gothic, in 2015 at the Birmingham Museum of Art while taking a graduate-level class, Photography in the South.4 This experience made its mark on Lunsford’s series All the Place You’ve Got. This essay considers Lunsford’s portfolio as a photographic road trip and places his works into dialogue with those of Lee Friedlander (b. 1934), Stephen Shore (b. 1947), Walker Evans (1903–1975), and William Christenberry (1936–2016). Through this comparison, we gain a glimpse of the South as both a literal and metaphorical space, and consider its iconographic, aesthetic, and cultural significance within the history of American road photography.

All the Place You’ve Got comprises thirty-six photographs, all untitled but identified with a location and year.5 In interviews, Lunsford describes how the project began during a period when he was seeking emotional and physical solitude. He would take long drives and photograph along the way as a form of release. The isolation of the towns and their relationship with nature became a perfect match for his personal emotional state. Each photograph began as a one-day road trip. Lunsford would start on Corridor X, drive to a new exit, and then roam through nearby towns.6 At the end of the day, Lunsford would get back on Corridor X and head home. He did not use GPS during these trips until he was going home. Instead, he would rely on what he saw and felt in order to make decisions about a turn.7

Based on the chorological order of images, Birmingham, AL, 2015 (fig. 1) is the first photograph taken during this project. Lunsford constructs his image with multiple layers of pictorial space. A storefront window clearly reflects the utility pole and wires, which stretch across the upper register of the image, in front of a painterly sky at dusk and the darkened silhouettes of trees. Inside the store, the screens from stacks of televisions and a space along the wall at left reflect a view of the street beyond. The sky perfectly fits within the composition, as if it were a Surrealist photocollage. Soon, however, the viewer realizes that it is a reflected image—with the televisions in front of the photographer and the landscape behind.

Many of Lunsford’s photographs are reminiscent of the work of his predecessors, in this case, those of Friedlander and Shore.8 Since the late 1960s, Friedlander and Shore have consistently documented America through cross-country road trips. Friedlander is known for his idiosyncratic approach to organizing the pictorial space through the reflections of mirrors and windows. For example, in Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, from 1969, Friedlander captured two tourists with binoculars looking at something. The reflection of a large window behind them reveal their view: the faces of four presidents carved on Mount Rushmore. In turning away from the vista—Mount Rushmore—and instead strategically framing the monument in the reflection, Friedlander demonstrates his sophisticated sense of composition and his consideration of the relationship between a spectacle and its audience.

In a similar way, Shore’s West Third Street, Parkersburg, West Virginia, May 16, 1974 (fig. 2), demonstrates an interest in reflections and quotidian subject matter.9 Shore roamed small towns photographing main streets, storefronts, and shop windows in color. Along with other Southern pioneers in color photography, such as Christenberry, Shore’s choice to shoot in color was radical, as color photography was not considered a legitimate form for fine art photography at the time. In comparison with Lunsford’s storefront image, Shore’s picture is bright and clear, shot during the day. Shore was obviously attracted to the display of lightbulbs, especially the juxtaposition between the clear, opaque, and colored ones, as well as the reflection appearing at the left of the image coincidentally positioned on the sidewalk. Using an offset composition, Shore created a dynamic image and avoided the reflection of himself. Lunsford also omitted his own reflection by not frontally photographing the shop window. Finally, Shore used a large-format 8 x 10 view camera, whereas Lunsford used a handheld Fujifilm X100T camera. Since Lunsford’s camera has a wide-angle 23mm fixed lens, he had to approach his subject very closely. He even recorded the dust and other marks on the shop window, which read as vertical texture over the sky.10

In contrast to an avoidance of the photographer’s reflection, Friedlander often intentionally includes reflections or shadows of himself in his photographs to suggest the presence of the artist. In New Orleans, 1968, Friedlander photographed a shop window frontally in order to document himself and the urban landscape behind him, along with a bystander. Likewise, for Lone Star Café, Texas, 1965 (fig. 3), Friedlander consciously captured his shadow in the foreground of the picture. Although including the artist’s reflection or shadow may be considered a rookie mistake for conventional documentary and fine-art photography, this became a hallmark of Friedlander’s style and visual language.

In All the Place You’ve Got, Lunsford also incorporates this pictorial mechanism at times. For example, in Sayre, AL, 2016 (fig. 4), he recorded his shadow cast across the warm light on roadside trees. The tree line recedes to the right of the image, following the curve of the road. The light from the sunset—which radiates from behind the photographer—coincidentally focuses only on part of the trees, providing a juxtaposition between the illuminated red foliage and the natural dark green tone of the trees. Lunsford is silhouetted against this roadside scene, rendering the artist present within an ordinary bucolic yet lonely Southern landscape.

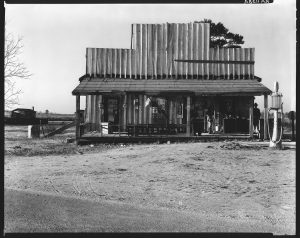

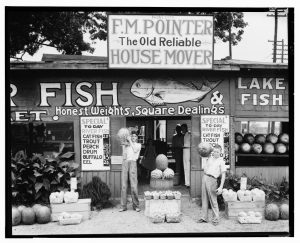

As one travels on the road frequently, the gas station and the farm stand become stops of necessity; therefore, they are an inevitable theme in road photography. Lunsford’s work is reminiscent of photographs of the roadside services and places documented by his predecessor, Evans, but in color. In the 1930s, Evans traveled extensively in the South, picturing rural America for the Resettlement Administration (RA-FSA; later known as Farm Security Administration). For his RA-FSA assignment, Evans was tasked with documenting the faces of America, including the local businesses and people. Evans created meticulous compositions that record automobile culture, the roadside landscape, and the signage and storefronts of small towns.11 These themes are seen in Country Store and Gas Station, Alabama, 1936 (fig. 5) and Roadside Stand near Birmingham, 1936 (fig. 6). Evans photographed these images with a large-format 8 x 10 camera to ensure better image quality for reproduction.12 For Country Store and Gas Station, Alabama, Evans cropped the lower foreground of the photograph when reproduced but provided significant distance between the store and himself in the original negative. The distance not only suggests that the station is located on open ground, presumably on the roadside in a rural area, but also creates a sense of detachment. Upon closer examination, the store has false doors with advertisements.13 In addition, two African Americans appear on the porch, suggesting this store might be one of the African American–friendly roadside facilities and services in the region. For Roadside Stand near Birmingham, Evans interacted with two boys at the farm stand as he set the camera on a tripod, allowing them to pose holding watermelons while a young girl, partially obscured by shadow, poses inside the building. Signage was one of Evans’s primary photographic interests, and this interest is manifest in these two images.14 Both photographs were included in his monumental book American Photographs, which accompanied an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938.15

Lunsford’s Mulga, AL, 2017 (fig. 7) echoes Evans’s Country Store and Gas Station, Alabama. The sign clearly reads “We now have gasoline,” suggesting that gasoline was once not available at the station. The gas pumps are antiquated and cannot take credit cards. In an interview, Lunsford stated that he was drawn in by the juxtaposition between the contemporary advertising, the antique gas pumps, and the handmade sign, which indicated that the owner was desperate for business.16 Similar to the formalism epitomized by Evans, Lunsford carefully positioned the light blue sign in between the green trees and red framed mart in the background. Through multiple layers of pictorial space, the viewer connects the green trees in the background and the verdant plant growing next to one of the pumps in the foreground. Furthermore, the geometric form of the manmade landscape—the building, the sign, the gas pump, and the lamppost—are juxtaposed with the organic form of the natural landscape. Lunsford’s view is unpopulated, quiet, and desolate, which intensifies the loneliness of the place. This is different from Evans’s documentation of places with people, as seen in the previous two photographs, which suggest the presence of a local community even in the depths of the Great Depression.

In All the Place You’ve Got, the conversation between the built environment and the natural world is a consistent refrain. This seems to be a nod to the fundamental aesthetic interests of New Topographics, a 1975 photographic exhibition and movement that emphasized the transformation of the American landscape, its topography, and its iconography. This movement reflected on the depiction of the West, particularly the change of the postwar human-altered landscape of urban sprawl and suburbanization from classic nineteenth-century images of Westward Expansion.17 Some of New Topographics images document the ways in which the automobile and highway culture significantly changed American life and landscape. While conventional landscape photography formerly focused on idealized nature, signs of human intervention dominated the images of the New Topographics.18

The theme of the American landscape, especially the West, was depicted in the nineteenth century with epic qualities, sentimentality, and romanticism.19 On the other hand, Lunsford’s photographic representations of the South tend to evoke a different atmosphere. He often captures the ways in which the built environment either advances or retreats in relation to nature. Some landscapes in the series, such as West Jefferson, AL, 2017 (fig. 8), take this to the extreme and seem to verge on the postapocalyptic. Lunsford recorded a nocturnal view of Plant Miller, a coal-fired electrical generation facility located in West Jefferson, Alabama. The vapor emitted from the cooling towers creates a painterly, atmospheric effect against the dark sky. This industrial landscape embodies a visually appealing but environmentally unsettling idea of the sublime. In 2017, Plant Miller was cited by the Weather Channel and the Environmental Protection Agency as the largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in the United States.20 Lunsford’s image is beautiful, yet it also delivers an ecocritical message regarding the Southern landscape.

Lunsford’s Cordova, AL, 2016 (fig. 9) is another noteworthy nocturnal scene in the series. The photograph was taken from the roadside and shows a cross half lit in an open field. Upon closer examination, one notices the string lights extended at far left.21 Lunsford does not approach the half-lit cross but positions it in the center of the image looming over the horizon line. The cross is in silhouette, along with the trees on the right. The dim orange light at the cross’s right edge is set against the dark blue sky and the pitch-black foreground. On one hand, the South is filled with religious iconography that Lunsford finds fascinating both visually and thematically, especially in relation to the Southern Gothic. As he states in an interview, for him the half-lit cross was symbolic of the deeply flawed characters, commonly depicted in Southern Gothic literature, whose actions do not meet up with what they claim to believe in.22 On the other hand, the distant cross may evoke the unsettling visual culture of the burning cross, especially in the South. Lunsford’s lyrical photograph of this eerie scene reflects upon the loaded histories related to Southern heritage.

Another common yet unsettling theme in the rural South is the practice of shooting at road signs, as documented by Lunsford in Sumiton, AL, 2018 (fig. 10). A road sign says, “Enter Jefferson County.” Presumably meant to welcome the visitors near the outskirts of the county border, the sign is riddled bullet holes, suggesting the aftermath of the shooting and an unruly, unwelcoming community. The image references the theme of violence in the Southern Gothic as well as the realities of violence in Jefferson County, which has one of the highest occurrences of violent crimes in Alabama.23 There are various reasons for people to shoot a road sign, whether it is for target practice or as a political statement, or even out of boredom. The person may be intoxicated or not, and the action could be planned or entirely random, since Alabamians are permitted to drive with concealed firearms in their vehicles.24 The violence enacted upon this road sign may not be an isolated incident. For example, the Emmett Till Memorial Sign, which marks the place where the body of Till—who had effectively been lynched—was pulled from the Tallahatchie River, near Glendora, Mississippi, has intentionally been repeatedly shot.25 Despite the different contexts for these two cases, in both, shooting marks territory or leaves proof of one’s presence.

Many of Lunsford’s photographs were taken serendipitously while aimlessly driving through rural Alabama. In Nauvoo, AL, 2018 (fig. 11), he encountered a site of shoe-tossing, the vernacular practice of tossing shoes with tied laces over powerlines or tree limbs.26 The tree, which appears prominently in the image, grows across the street from a graveyard. Because of this fact, Lunsford interpreted the tree as a memorial of some kind.27 The haunting quality of the shoes hanging from their laces is striking, especially as they also evoke the 340 documented lynchings of African Americans that occurred in Alabama between 1877 and 1943.28

As demonstrated, Lunsford’s images are deeply embedded in the histories of Southern photography. In fact, the project initially originated during a pilgrimage to revisit the Sprott post office in Alabama that Walker Evans photographed in 1936, reproduced in Let Us Now Famous Men (fig. 12), and Christenberry’s Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama (fig. 13). Christenberry, who often shot in color and is known for his depiction of Southern roadside architecture and place—especially Hale County, Alabama—once stated: “I am attracted to things that are decaying, that are rapidly vanishing from the landscape in the South. I cannot say I am obsessively attracted to them. I find them ugly.”29 Lunsford’s work embodies similar notions, especially in the production of a concentrated body of work focusing on a singular location over time. Indeed, Corridor X may be to Lunsford what Hale County was to Christenberry. Both Christenberry and Lunsford sought to capture the vanishing South in melancholic photographs. While Lunsford is a great admirer of Christenberry’s work, he describes himself as, first and foremost, an outsider to the South, despite the fact that he has now lived in the South for half of his life.

Lunsford moved to the South from the Midwest along with his family when he was twelve years old. This gives him a different perspective on the region. In Alabama, Lunsford therefore exists as both an insider and an outsider, with a sense of alienation that drives him to see his surroundings with fresh eyes.30 For many of us, America is hard to see, borrowing Robert Frost’s poem,

America is hard to see.

Less partial witnesses than he

In book on book have testified

They could not see it from outside—

Or inside either for that matter.

We know the literary chatter.31

Perhaps, similarly, the South is hard to see. Many scenes and things in Lunsford’s photographs are signifiers of a region in decline: out-of-date TV sets, roadside gas stations, backroads, signs, abandoned places, crosses, and bullet holes, among others. Meanwhile, they evoke and perpetuate the romantic myth of the rural South.32

Lunsford acknowledges his connections to previous American photographers who documented the South, explaining that it is hard to be a fine art photographer in Alabama without obliquely referencing Evans and Christenberry. While Evans’s images of the South are empathetic, yet still shot with an outsider’s gaze, Christenberry had a sensitivity and respect for the rural South while also being aware of its complexities. Through All the Places You’ve Got, Lunsford tries to capture the same empathetic yet unflinching view of places similar to those documented by his predecessors, but with his own intentions.

Lunsford’s photographs visually resonate some quintessential qualities in contemporary Southern Gothic literature, particularly in the work of Cormac McCarthy, “an imagination haunted by a frightening vision of destruction and waste” that seems “simultaneously pre- and post-human.”33 At the same time, the intersection of the camera, car, and road has significantly defined the history of American photography since the early twentieth century, including in the American South. This enduring marriage between photography and automobile travel is evidenced by the photographs of Evans, Friedlander, Christenberry, and Shore, and carried on in Devin Lunsford’s portfolio All the Place You’ve Got. Through the genre of road photography, the camera granted these artists permission to enter remote places in the American South while exploring their own relationship to the place.34 Lunsford becomes one of the latest in a lineage of photographers who, as artists who themselves are in motion, are particularly good at documenting the communities in flux, even in a remote corner of Alabama. This particular genre, or mixture of genres—of road and Southern photography—remains vital, with its own artistic merits that illustrates the art of the American South.

Cite this article: Peter Han-Chih Wang, “Roaming in the South: Devin Lunsford’s Photographs from the Roadside,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9947.

PDF: Wang, Roaming in the South

Notes

I originally presented this essay as a paper at the Southeastern Art Association Conference in Birmingham in October 2018. I wish to thank Devin Lunsford for the willingness to share his thought process, photographs, and image permission with me. My thanks are also extended to Naomi Slipp for organizing the session and this issue, as well as providing thoughtful comments on earlier drafts. I also appreciate the assistance of Diana Greenwald with this revision.

- See Devin Lunsford, All the Place You’ve Got (Austin, TX: Cattywampus Press, 2019). ↵

- Devin Lunsford, interview with the author, September 26, 2018. Lunsford states that he had fallen into the work of Flannery O’Connor and the whole genre of the Southern Gothic, as the places he visited felt reminiscent of the ones depicted in the novels. For the genre of Southern Gothic, see Thomas Ærvold Bjerre, “Southern Gothic Literature” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, June 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.304. ↵

- Lunsford, All the Place You’ve Got, unpaginated. ↵

- Lunsford, All the Place You’ve Got, unpaginated. The class was taught by Jared Ragland, and Lunsford looked at prints by Sally Mann, William Christenberry, Bruce Davidson, Birney Imes, Gordon Parks, and Debbie Fleming Caffery, among others, for the curatorial research. See Inherited Scars: A Meditation on the Southern Gothic, April 2–August 9, 2015, Birmingham Museum of Art, accessed March 9, 2020, https://www.artsbma.org/exhibition/inherited-scars-a-meditation-on-the-southern-gothic. ↵

- Although no captions are shown on the artist’s website or photobook, Lunsford has kept a checklist of location and year for reference, which he shared with the author. ↵

- The Appalachia Development Highway system developed as part of the Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965. The 3,090 mile system consists of a mixture of state, federal, and interstate highways, and was designed to generate economic development in previously isolated areas. Each section is categorized as a corridor from A to Z. It ranges from New York and Pennsylvania to Southern states, such as Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Both Corridors V and X cross the state of Alabama. See “Appalachian Development Highway System,” Appalachian Regional Commission website, accessed May 2, 2020, https://www.arc.gov/program_areas/AppalachianDevelopmentHighwaySystem.asp. ↵

- Lunsford interview. ↵

- For a thematic overview, see, for instance, John Szarkowski, Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978). ↵

- Lunsford interview. In fact, Lunsford stated that he was, and to an extent, is still heavily influenced by the 1975 photography exhibition New Topographics. See William Jenkins, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, exh. cat. (Rochester, NY: International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1975). Shore was one of the artists included in New Topographics and the only photographer who shot in color. ↵

- One of the major differences between using a large-format view camera and a handheld camera is that the former often requires a tripod due to its cumbersome size and weight, and the image is upside down on the ground glass on the camera, which results in a more analytical view in the process than using the handheld camera. By contrast, with the point-and-shoot camera, a photographer can often photograph more spontaneously. Stephen Shore used a Rollei 35mm camera for his series American Surfaces, 1972–73, with images in a snapshot style, an aesthetic exemplified by Robert Frank, before switching to a large format for his Uncommon Places, 1982, a tradition epitomized by Walker Evans. See Stephen Shore, American Surfaces (Berlin: Phaidon, 2005); Uncommon Places: The Complete Works (New York: Aperture, 2004). ↵

- Evans was one of the first photographers that Roy Emerson Stryker hired for the historical section of the RA-FSA. During the formulation of the RA-FSA, Rexford G. Tugwell, the first director and Stryker’s mentor, had suggested that the project “Introduce Americans to America.” In a letter to all photographers, Stryker listed pictures needed for RA-FSA files, and Highway was one of the themes, as he described: “pictures which emphasize the fact that the American highway is very often a more attractive place than the places American live.” See Marilyn Laufer, “In Search of America: Photography from the Road, 1936–1976” (PhD diss., Washington University, 1992), 109, 111. For the Stryker letter, see Stu Cohen, The Likes of Us: America in the Eyes of the Farm Security Administration (Boston: David R. Godine, 2009), 25. ↵

- Evans carried both a 35 mm and a large-format 8 x 10 camera for his RA-FSA assignments. He mainly used the large format because many photographs were meant to be reproduced for publication later, especially for newspapers and magazines to educate the public. See Jeff L. Rosenheim, “’The Cruel Radiance of What Is’: Walker Evans and the South,” in Walker Evans, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 69–70. ↵

- This photograph is titled Country Store and Gas Station, Alabama in Evans’s American Photographs (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012). However, by cross-referencing the FSA Collection in the Library of Congress, the photograph is labeled under the title Store with False Front, Vicinity of Selma, Alabama. Evans made at least two shots, including the distant uncropped view (LC-DIG-fsa-8c52061) and a separate exposure with detail of the façade (LC-USF342-T01-001139-A). Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. ↵

- For Evans’s extensive interest in depicting signage, see Walker Evans et al., Walker Evans: Signs (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1998). In addition, Evans’s father was a copywriter for an advertising agency, which possibly informed Evans’s appreciation for graphic design and its relationship to architecture. See “The Exacting Eye of Walker Evans,” Florence Griswold Museum website, accessed April 1, 2020, https://florencegriswoldmuseum.org/exhibitions/online/the-exacting-eye-of-walker-evans. ↵

- Both photographs were included in the photobook and the exhibition. While the exhibition had 100 photographs, the book contained eighty-seven images, fifty-four of which were part of the exhibition. For a closer examination of the difference between the photobook and the exhibition, see Jessica Lee May, “Off the Clock: Walker Evans and the Crisis of American Capital 1933–38” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2010). Evans was aware of the ephemerality of the exhibition and the extended life of the book in terms of its readership. For Evans, the book became the primary vehicle to best present his work. See John T. Hill, “American Photographs: Legacy of Seeing” in American Photographs (New York: Errata Editions, 2011), unpaginated. ↵

- Lunsford, interview. ↵

- The exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape was first held in 1975 at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, with participating artists including Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel Jr. See Jenkins, New Topographics. ↵

- Juha Tolonen, “New Topographics: Withholding Judgement” in Photography and Landscape by Rodney James Giblett and Juha Pentti Tolonen (Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2012), 156. ↵

- Alison Nordström, “After New: Thinking about New Topographics from 1975 to the Present” in New Topographics, 76. ↵

- See Eric Chaney and Elizabeth Hernandez, “The Worst Greenhouse Pollution in America and the Place that Relies on it,” a special coverage on the United States of Climate Change by the Weather Channel, accessed April 2, 2020, https://features.weather.com/us-climate-change/alabama. ↵

- Lunsford, interview. ↵

- Lunsford, interview. ↵

- Lunsford, interview. ↵

- Alabama law allows residents to have unloaded hunting rifles in their vehicles without a concealed-carry permit. Evan Belanger, “Six things to know about Alabama’s new gun law 6 days before it takes effect,” AL.com, accessed April 2, 2010, https://www.al.com/wire/2013/07/six_things_to_know_about_alaba.html. ↵

- By 2019, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission had already replaced the sign for the third time and decided to install a bulletproof sign to prevent vandalism due to racial crime. For the coverage, see Kayla Epstein, “This Emmett Till memorial was vandalized again. And again. And again. Now, it’s bulletproof,” Washington Post, October 20, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/10/20/this-emmett-till-memorial-was-vandalized-again-again-again-now-its-bulletproof. ↵

- The legend of shoe tossing remains a mystery, as it has many different connotations, including murder, sex, drugs, art, and politics, among others. See The Mystery of Flying Kicks, directed by Matthew Bate (Melbourne, AU: Closer Productions), accessed April 2, 2020, https://vimeo.com/71867019. ↵

- Lunsford interview. Upon further research based on the name written on some sneakers, this memorial is presumably for Hannah Diane Bridgmon, killed in a car accident in 2017. Bridgmon was buried in Ashbank Freewill Baptist Church Cemetery, Nauvoo, Alabama. For the obituary and coverage, see https://www.pinkardfh.com/obituaries/Hannah-Bridgmon/#!/Obituary and http://archives.etypeservices.com/Northwest1/Magazine167333/Publication/Magazine167333.pdf, both accessed May 8, 2020. ↵

- Lunsford interview. Upon further research based on the name written on some sneakers, this memorial is presumably for Hannah Diane Bridgmon, killed in a car accident in 2017. Bridgmon was buried in Ashbank Freewill Baptist Church Cemetery, Nauvoo, Alabama. For the obituary and coverage, see https://www.pinkardfh.com/obituaries/Hannah-Bridgmon/#!/Obituary and http://archives.etypeservices.com/Northwest1/Magazine167333/Publication/Magazine167333.pdf, both accessed May 8, 2020. ↵

- William Ferris, The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 175. ↵

- Ferris, The Storied South, 175. ↵

- Robert Frost, “America is Hard to See,” originally published in Atlantic in 1951. For the full text, see the website for Amy Kass and Leon Kass, What So Proudly We Hail: The American Soul in Story, Speech, and Song (Wilmington, DE: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2013), accessed May 21, 2020, https://www.whatsoproudlywehail.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Frost_America-is-Hard-to-See.pdf. ↵

- Ferris, The Storied South, 175. ↵

- Ferris, The Storied South, 175. ↵

- Lunsford interview. ↵

About the Author(s): Peter Han-Chih Wang is a Lecturer in the Department of Art at Butler University