Louis Carlos Bernal’s Photographs of TV Screens and Domestic Interiors

PDF: Wingate, Louis Carlos Bernal’s Photographs

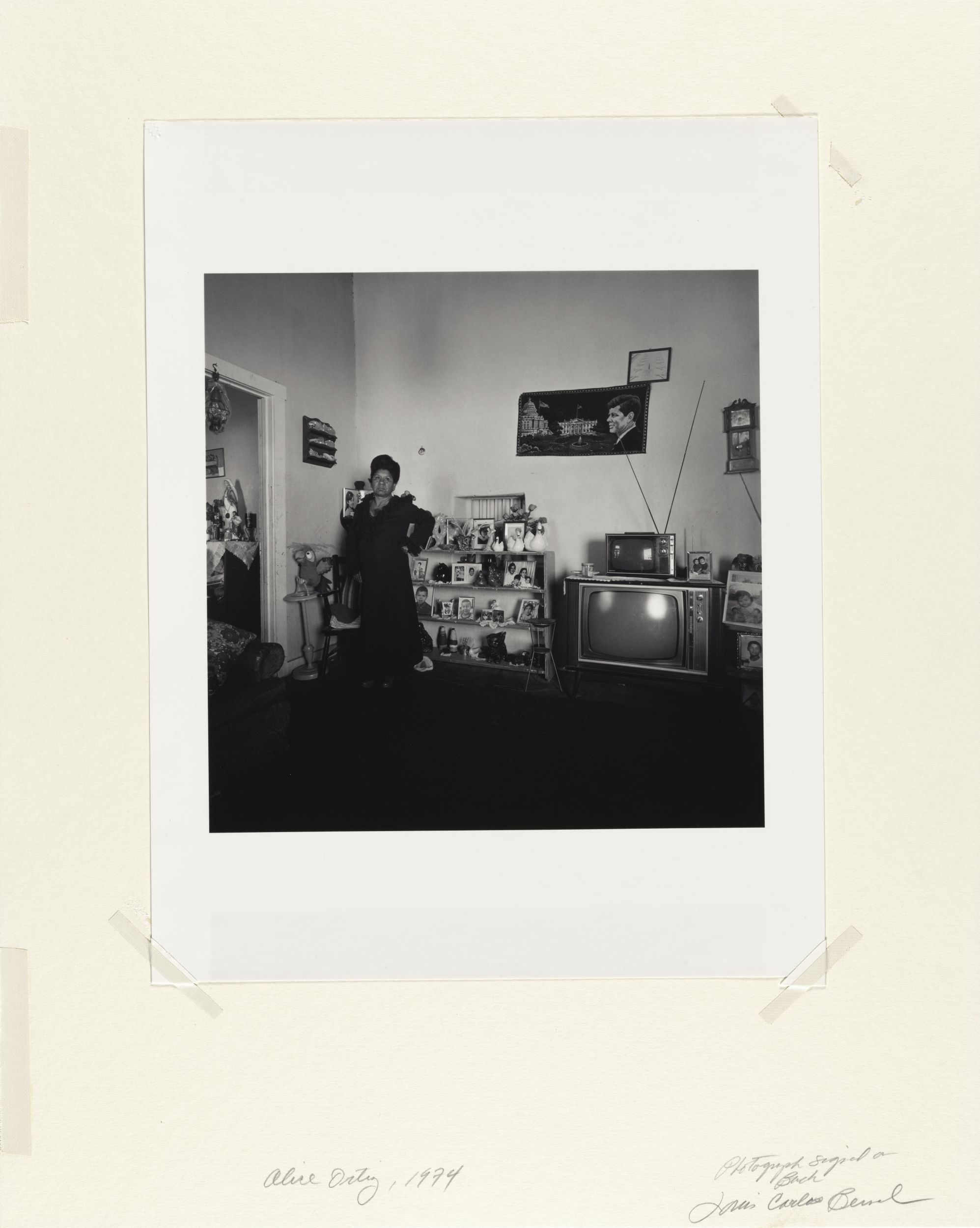

While researching photographs of domestic interiors in the papers of Louis Carlos Bernal (1941–1993), I saw several images that invited me to think about the meaning of television for his practice, including shots of televised broadcasts of John F. Kennedy and photos of Mexican American subjects in their homes beside their TV sets. One such image formally connects a woman named Anita Ortiz with a commemorative John F. Kennedy tapestry hanging on the wall of her living room (fig. 1). The tapestry, a tribute to the thirty-fifth president as well as a marker of North American belonging, hangs above two stacked TVs. The sets, with their blank but gleaming screens, were the means by which JFK’s image entered US homes in the 1960s. Much of Bernal’s work from the 1970s and 1980s features intimate portraits of southwestern neighborhoods at a time when TV coverage of Mexican American life and politics was far less nuanced and when the Chicano Movement had empowered Mexican Americans like Bernal to “take ownership of their lives and the representation of Mexican American politics, art and culture in the public sphere.”1 Bernal’s photographs involving televisions show him bearing witness to US presidential politics in ways that are relevant to and lend insight to his photographs of interiors.

Taking still photographs of moving television images, a practice historian Lynn Spigel calls taking “screenshots,” first emerged among hobbyists in the 1950s and soon began to interest professional photographers like Bernal.2 For hobbyists, the impulse to photograph television merged two new technologies that became widely available in the early 1960s. TVs had entered 90 percent of homes by 1960, and by 1963, the new Kodak Instamatic camera made taking pictures easier than ever.3 Spigel also describes the practice as fulfilling an urge to capture history as it was unfolding and to assert one’s presence at national events, like JFK’s funeral or the moon landing, even at a remove.4 I have come to see Bernal’s screenshots of Kennedy within the photographer’s larger professional output as reflecting his investment in US politics and in the lives of Arizona’s Mexican American communities. His art practice and the cultural expressions of his subjects both embody ideals of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, including Chicanismo, which Bernal describes as “a new sense of pride, a new attitude, a new awareness.”5 Bernal’s agency in photographing televised political figures, in particular Kennedy, echoes the choice of his subjects to incorporate JFK’s image into their decorative and religious displays.

At Home with Political Portraits

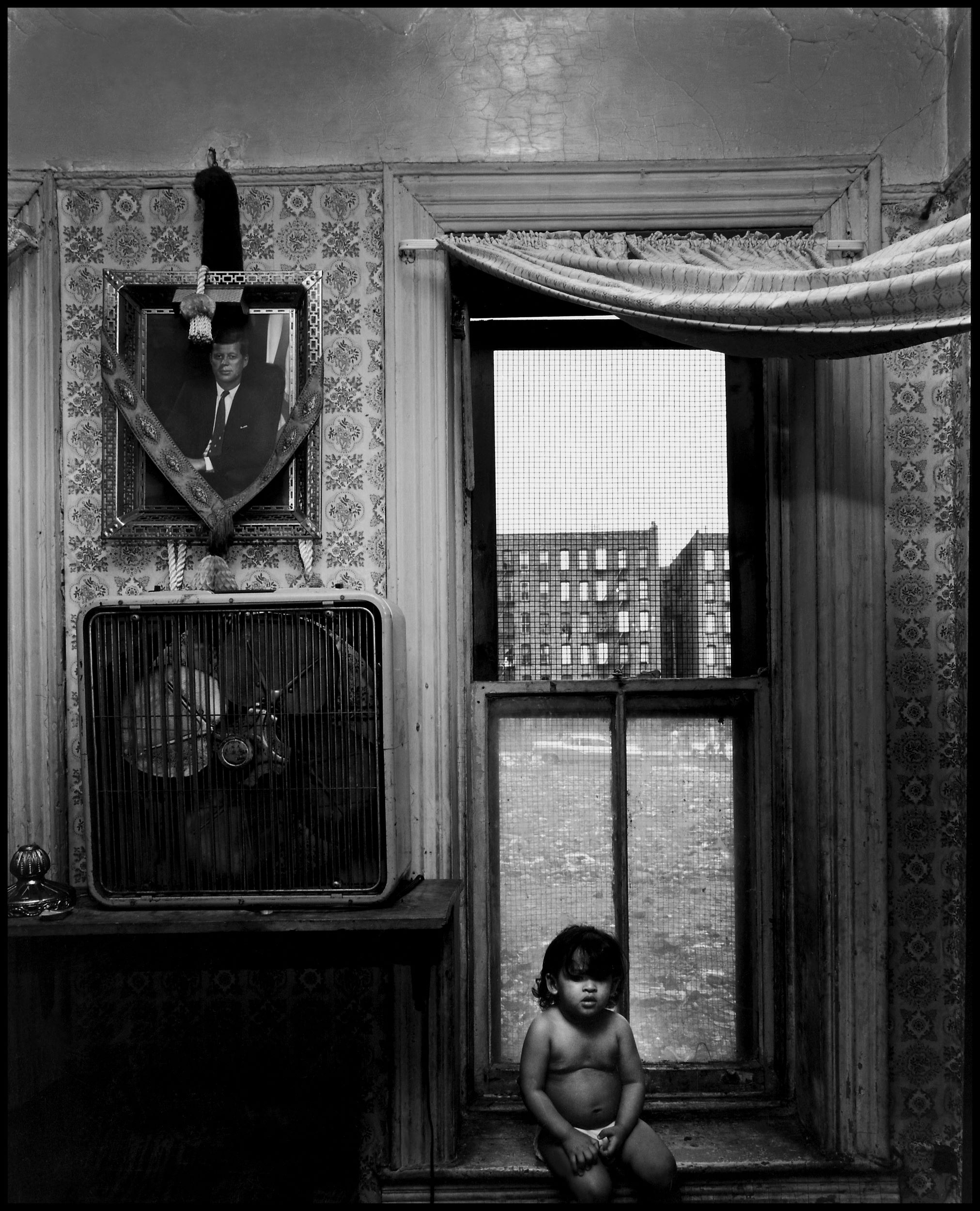

This research is part of my larger project concerning photographs of domestic displays of presidential portraits; my chapter on Kennedy focuses on images by Bernal and Bruce Davidson (b. 1933) (fig. 2).6 An examination of how and why photographers like Bernal and Davidson captured Kennedy portraits in US homes demands a consideration of the president’s televised image. Franklin D. Roosevelt was the last president before JFK whose portrait had been widely displayed in homes and businesses.7 For those who had listened to FDR’s voice in their living rooms during his radio broadcasts, Roosevelt felt almost like a member of the family.8 In an even more direct way, TV forged a sense of intimacy with Kennedy, since it provided a visual showcase for his charisma and charm within the homes of his constituents. Presidential historian Tevi Troy writes that TV put the president “into daily contact with the people more powerfully and with more immediacy than radio.” It gave “the president entrée into America’s homes, making him a constant visual presence, as familiar as a relative.”9 Garry Winogrand’s photograph of JFK accepting his party’s nomination at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, while a TV on stage behind him shows how his speech was televised live to the public, foreshadows the importance of TV for Kennedy’s campaign and presidency.

The time Bernal and Davidson spent photographing domestic interiors made them aware of cultural shifts precipitated by radio and TV. Several of the shots in Bernal’s Barrios (1977–78) and Davidson’s East 100th Street (1966–68) series feature television sets. The photographers’ own presence within their subjects’ home paralleled what might be understood as the eroding boundaries between public and private brought about by the new media. Coverage of Kennedy’s assassination and funeral in 1963 illustrated the new cultural dynamics of TV better than any previous national event. The four-day broadcast made an emotional impact on the nation, allowing home viewers to feel more like participants than spectators.10 TV’s “ability to transmit live images endowed the medium with a visual and cultural authority,” encouraging viewers to conflate “direct experience with the televised image.”11 The mid-1960s and after were a period “when private and public images collide[d]” and came into dialogue with one another more than ever.12

Bernal and Davidson not only focused their cameras on portraits of JFK among the decorative, cultural, and religious household effects of US homes, as many photographers did, but they both returned to the subject on numerous occasions. Photography scholars Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart distinguish between images “hidden away in boxes, lockets, wallets or family Bibles,” like a JFK prayer card, and those that are “displayed, formally framed in the semi-public spaces of the home. . . . There are profound cultural differences and . . . significances,” they write, “in what is displayed, in what contexts, who has access to it, [and] how long it stays there.”13 Bernal and Davidson, who captured these displays in the frames of their photographic shots, draw our attention to these presidential portraits as objects of cultural import, thereby capturing the relationships between individuals and the nation.

Why JFK?

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund commissioned Bernal and four other photographers to create a survey celebrating Mexican American life for a 1978 exhibition at the Oakland Museum titled Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American. Bernal chose to continue his practice of photographing Chicana/o residents of Tucson and Douglas, Arizona, including many images of individuals and families in their homes; these came to be known as his Barrios series.14 The featuring of Kennedy portraits and souvenir tapestries in the homes that Bernal photographed was part of his strategy to amplify the cultural agency of his subjects. The combination in the photos of JFK’s presence alongside markers of Mexican and mestizaje culture underscores the subjects’ Chicana/o identity, marking their homes as culturally distinct spaces.

Kennedy portraits had begun to enter the homes of minority groups in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, when the president was recast as a martyr figure. His portraits were tributes to a time of hope that JFK’s incomplete term as president had come to embody. Kennedy’s status as the nation’s first Catholic president and the first candidate to win with a minority of Protestant votes was also a meaningful source of pride for ethnic groups with large Catholic majorities.

Bernal’s contact sheets and negatives reveal additional unpublished photos showing the presence of Kennedy’s image in the lives of his subjects. One features a woman standing outside her home, holding a framed portrait of JFK. A black-and-white print of Abraham Lincoln is tucked into the corner of its frame, positioning Kennedy as the inheritor of Lincoln’s mantle.15 In the popular imagination, both were martyrs for civil rights, as were Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy. “As anyone who may have visited a working-class African American or Latino home in the late 1960s and early 1970s knows, [the] tripartite portrait of ‘The Holy Trinity of the Civil Rights Movement’ was standard decorative fare and/or a semi-religious element in these homes,” writes art historian Richard Powell of the popularity of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy portraits. Their “untimely death from assassins’ gunfire, along with the belief that these men died while serving the poor and oppressed, fueled their status as martyrs in the minds of many, and transformed them . . . into divinities.”16 When Bernal started photographing people in their homes in the early 1970s, such romanticization of JFK was still at a peak.

Art historian Charles Coffey suggests that Bernal’s focus on subjects in their homes surrounded by their personal belongings can be seen as a meditation on the right to space and therefore related to the Chicano Movement’s investment in Chicano nationalism and homeownership.17 In Bernal’s papers, there are negatives and contact sheets showing a woman seated next to a curio cabinet, as well as a print of the cabinet alone, filled with family photos and souvenirs tucked in among tea cups and glassware.18 The largest photo is a portrait of JFK, peering out from behind Disney figurines on the bottom shelf. The Kennedy portraits visible in so many of Bernal’s interiors underscore his subjects’ right to their own space in the United States and assertion of their Americanness.

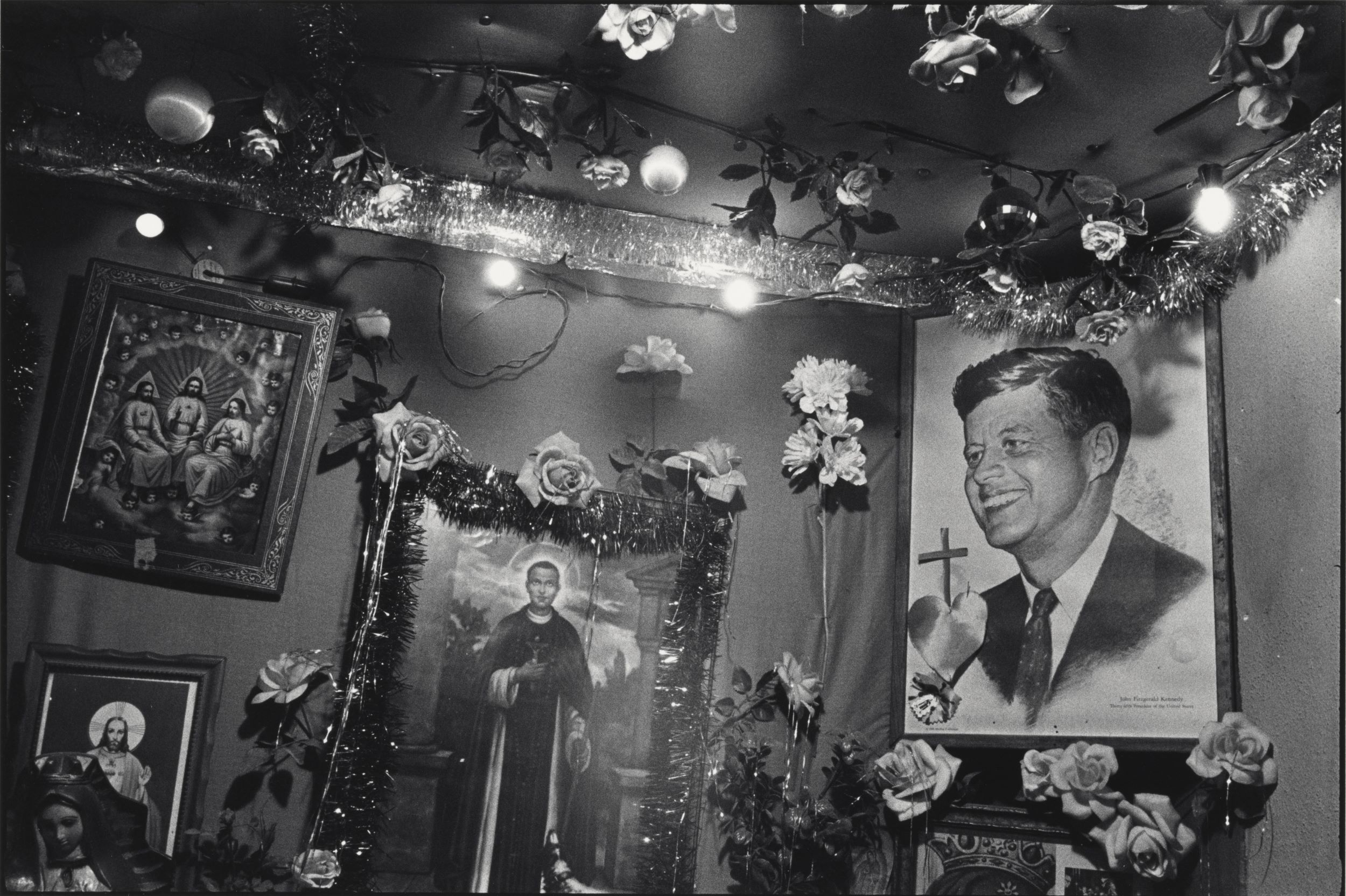

Bernal’s photograph Rosie Siqueiros, Barrio Anita, Tucson, Arizona (fig. 3), succinctly visualizes this claim by underscoring a one-to-one correspondence between Siqueiros and the image of Kennedy on the wall of her Tucson home. A dark JFK commemorative tapestry interrupts an expanse of cream-colored living-room wall, an obvious counterpart to the figure of Siqueiros on the couch below. In the tapestry, Kennedy looks out contemplatively, echoing Siqueiros’s expression, just as his dark suit matches her outfit. Kennedy and Siqueiros are connected by the strength of their visual presence. The red accents in JFK’s tie and in the US flag beside him also visually link him with the sofa on which Siqueiros sits and the pillow on her lap. Bernal’s contact sheets reveal multiple other photographs during this shoot that diluted or distracted from this one-to-one identification between Kennedy and Siqueiros, reinforcing the idea that he chose to print this particular shot because it highlights their alliance.

Other photographs show interiors where Kennedy’s portrait is displayed in or beside home altars. The cocio (chocolate) in the title of Kennedy Cocio Altar (fig. 4) is a reference to the sweet offerings presented at such altars to lure the deceased back home. By photographing this altar—and returning again and again to the subject of Kennedy in his photographs of Mexican American subjects in their homes—Bernal acknowledges the complex and multilayered notion of the home. Scholars Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling propose a critical geography of home, in which “home is a spatial imaginary, a set of intersecting and variable ideas and feelings, which are related to context, and which construct [and connect] places, [and] extend across spaces and scales.”19 In this and other Barrios photographs, the altars and domestic décor articulate the home, a space traditionally the purview of women, as the self-styled intersectional space of Chicana identity.20 Bernal’s photo captures the portion of the altar that puts a JFK portrait in conversation with a framed print of the Peruvian friar Martín de Porres, one of the most popular Latino saints and the patron saint of mixed-race people, racial harmony, and social justice. Their likenesses are adorned with flowers, tinsel, and lights, showing the care with which home altars are crafted and the intentionality of this juxtaposition of two men from different periods and cultures who both sacrificed for the common good.

Television Screenshots

What should we then make of Bernal’s photographs of television screens with footage of JFK?21 The motives behind Bernal’s screenshots are hard to know with certainty, since they are not among the images he chose to print, and his career was cut tragically short, hindering us from knowing the extent of his intentions with this project.22 However, the presence of Kennedy in both Bernal’s screenshots and his photographic subjects’ homes reveal that Bernal considered it important for a photographer to engage with and offer testimony to the political events that shape the world. Of the photographs Spigel gathered in her research for TV Snapshots: An Archive of Everyday Life, she singles out two Kodak prints (c. 1962) with a TV screen showing a headshot of JFK. She claims these demonstrate how hobbyists performed their own personal orientation to televised national events by documenting them in photographs, within the frame of their own domestic settings. One of these prints in Spigel’s collection is labeled “Kennedy” on the front, while the handwritten notation on the back reads “Kennedy / both photos taken on my TV in Springfield on John St.” This caption, asserting that the photographer took the photo in their own house, forges a link between the photographer and the president, and it records evidence of that connection for posterity. In a parallel way, Bernal’s screenshots likewise signaled his personal investment in US culture and politics.23

Bernal’s screenshot contact sheets also reveal a glimpse into the jarring world of 1960s and ’70s television programming. He took pictures of TV screens showing political icons, like JFK, and graphic war imagery, and these contact sheets share space in the Bernal Archive with other contact sheets of Senate hearings, Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral, and a commercial for Brightside shampoo. One of Bernal’s contact sheets of TV screens shows a close-up of Kennedy, his hand to his chin as he listens attentively (fig. 5).24 Because of the close-up’s location on the sheet, JFK’s gaze appears to be turning away from two images in the middle of the print: a child’s crying face and a shot of what is presumably the Buddhist monk Quang Duc, photographed by Malcolm Browne, as he is engulfed in flames after setting himself on fire to protest the Vietnam War. Another close-up of Kennedy’s eyes in the frame just below stare in the direction of these two harrowing war images. The contact sheet in its entirety reads as a sober reflection on death and foreshadows JFK’s assassination just months after Quang Duc’s suicide. Whereas the Kennedy portraits on the walls of Bernal’s subjects’ homes are recontextualized, having been turned into icons of veneration and assertions of Chicana/o pride, Bernal’s television screenshots reveal a darker US history, part of a longer trajectory of US imperialism.

Bernal was not a detached or passive observer engaging in a technical photographic exercise. He photographed televised broadcasts and saved the contact sheets that still exist today in his papers, which also include photographs of Kennedy on the campaign trail and images of workers’ strikes. An undated photomontage combining Bernal’s print of Kennedy campaigning, a torn-out newspaper portrait of JFK, and a headline reading “Kennedy Slain” reflects Bernal’s rumination on current events.25 His 1978 portraits of workers during the onion strike and of undocumented orange pickers, both outside Phoenix, demonstrate his ongoing interest in and solidarity with grassroots Chicano labor-rights activism.26 Those who knew Bernal understood the connection between his politics and art practice. With reference to the artist’s Barrios series, photographer and museum director James Enyeart writes,

On the surface, his barrio photographs of La Raza seemed to be admiring mirrors of the life and culture of Mexican Americans, but they were envisioned by him to reveal much more. They were about “Chicanismo” as he described them, which is a highly politicized reference to the nature of his work.27

“To be a Chicano,” Bernal said, “means to be involved in controlling your own life.”28 His practice reflects the role images and visual culture played in that effort.

A TV Portrait

The image with which I opened this essay serves to highlight Bernal’s engagement with TV as a fulcrum for Chicana/o identity (see fig. 1). In Bernal’s portrait of Ortiz in her living room, one can just make out, through a doorway to her right, a cluster of statuettes on a dark piece of furniture draped with a white table linen, perhaps a home altar or a decorative display. A stuffed parrot is propped on a small table between the woman and the doorway. Three ceramic swans are visible among the items on a bookshelf at the back of the main room, which is also lined with framed family portraits. The woman proprietarily inhabits the space in a long black coatdress, standing with one hand on her hip, at the helm of her environment. Her control of the space, with its personalized mixture of family photos and mementos, exemplifes what artist and scholar Amalia Mesa-Bains calls “domesticana rasquachismo,” a domestic version of the Chicano vernacular aesthetic.29 Scholar of US Latino culture Tomás Ybarrao-Frausto describes rasquachismo as a working-class sensibility characterized by resilience and resourcefulness, as well as a tension between public and private.30

The largest item in the room, to the right of the woman’s body and bookshelf, is a large freestanding TV, the private home’s “window onto the world.” It briefly interrupts the procession of family photos, which continues on its other side. A framed studio portrait of two small children rests on top of the TV, along with another, much smaller (probably newer) TV.31 Among the items on the wall above the stacked TVs are a clock and, most prominently, a JFK commemorative tapestry of the type found in many homes and businesses in the 1960s and ’70s.32 Bernal captures the former president’s portrait in a private home, on display in the living room for visitors to see, drawing our attention to public and private “tensions” that Ybarrao-Frausto identifies as characteristically Chicano.

This image has many of the hallmarks of Bernal’s published photos from his Barrios series: the presence of a JFK portrait among numerous items of personal significance and a spatial narrative that puts subjects in dialogue with their surroundings. In this photo, the woman, the TVs, and the Kennedy wall hanging are the most prominent compositional elements due to their size, placement, and tonal contrast with their surroundings. They form a triad, each anchoring a corner of a triangle. An antenna on the smaller TV reaches up to the tapestry, forming one side of the triangle and connecting the TV sets with the former president, physically and visually. The likeness of Kennedy on the tapestry is smiling, his head and shoulders in profile. He faces the side of the room where Ortiz stands, inviting us to look in her direction. The tapestry’s dark background also connects Kennedy visually with the woman’s dark housecoat. Her gaze, however, instead of completing the triangle or engaging the viewer, looks up and away. There are at least three shots of this scene in the Bernal papers; they are almost identical. In the printed version, the woman’s head is turned up and away, but her gaze is ever so slightly turned back toward the Kennedy tapestry.

There is no doubt Bernal was aware of the compositional triad linking the TVs, the Kennedy tapestry, and the woman. The TV was the vehicle for Kennedy’s stardom and martyrdom, having broadcast four days of news coverage about his death and funeral. It was a connection to the outside world, a link to political and popular US culture (and only gradually, beginning in the late ’70s, a link to Latino culture, with Arizona’s first full-time Spanish-language station).33 Even though most news broadcasts and popular shows ignored the Chicano population on which Bernal focused his camera, the television brought JFK into nearly every US home. Kennedy was an icon of US culture by the 1970s, and one that was celebrated by Bernal’s subjects and explored by Bernal himself.

Conclusion

In Bernal’s screenshots of Kennedy and in his photos of Chicana/o homes proudly displaying JFK portraits, we see the inseparable push and pull of Bernal’s Mexican and US worlds. Bernal’s pictures tread a line between the world of fine art photography (he was the head of a college photography program and art professor) and the vernacular realm of family snapshots made in living rooms with Instamatic cameras. Having lived through the ascendancy of TV and the growth of popular photography, Bernal was attuned to the dialogue between the two. There was more crossover than ever between the private life of the domestic sphere and the public life of the civic realm thanks to the increasing accessibility of photography and TV, but first-generation US citizens, like Bernal himself, were not well represented in the new media cultures. They formed and expressed their own Chicana/o values and did so, in part, in their homes, where they took control of their visual and material surroundings. Bernal, who came of age during the early years of the Chicano movement and who “wrestled with the injustices of racial prejudice most of his life,” also performed a personal orientation toward national politics in his unpublished screenshots as part of his ongoing interrogation of intersecting cultural spheres and identities.34

Bernal’s screenshots show us his personal investment in US culture and politics, just as the subjects in his Barrios series show us theirs. Contemplating Bernal’s screenshots in the context of Mexican American interiors featuring JFK’s portrait provides an opportunity to meditate on Chicana/o agency and on photography and television’s joint role in shaping and amplifying national and cultural affiliations.

Cite this article: Jennifer Wingate, “Louis Carlos Bernal’s Photographs of TV Screens and Domestic Interiors,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18951.

Notes

- Marc Simon Rodriguez, Rethinking the Chicano Movement (New York: Routledge, 2015), 10. See also Randy Ontiveros, “No Golden Age: Television News and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement,” American Quarterly 62, no. 4 (December 2010): 827–923. Bernal first came to my attention when I read Elizabeth Ferrer’s book Latinx Photography in the United States: A Visual History (Seattle: University of Washington, 2020). Ferrer curated a retrospective of Bernal’s photography for the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, in September 2024, and wrote the accompanying catalogue, Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografia (Tucson: Center for Creative Photography in conjunction with Aperture, 2024). Other scholarship includes Charlie P. Coffey, “Louis Carlos Bernal’s Barrios: The Politics of Domesticity in the Wake of the Chicano Movement” (master’s thesis, American University, 2021); and untitled essays by Ann Simmons-Myers and James Enyeart in Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios (Tucson: Pima Community College in Association with the University of Arizona Library, 2002). ↵

- See the section titled “Photographing Telepresence: Screenshots,” in Lynn Spigel, TV Snapshots: An Archive of Everyday Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 97–119. The painter Barkley Hendricks also took photographs of TV screens, including broadcasts featuring Ronald Reagan and Anita Hill’s 1991 testimony in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. His screenshots from the 1980s and 1990s were published and exhibited in 2020 and 2023, respectively. See Barkley L. Hendricks: Photography (Milan: Skira, 2020). ↵

- Matthew S. Witkovsky, “When the Earth Was Square,” in The Art of the American Snapshot, 1888–1978: From the Collection of Robert E. Jackson, ed. Sara Greenough and Diane Waggoner (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, in association with Princeton University Press, 2007), 230; Spigel, TV Snapshots, 70. ↵

- Spigel, TV Snapshots, 97. Magazines like Popular Photography and Popular Science published how-to columns in the 1950s and 1960s, and there is evidence that the hobby continued for decades, at least through the early 1990s. Magazines held contests, and practitioners often arranged their screenshots in albums. See also Ed Corley, “Try Filming TV!,” Popular Photography 53, no. 5 (November 1963): 183. ↵

- Enyeart, untitled essay, Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios, 13. ↵

- Jennifer Wingate, At Home with Political Portraits: Photographs of the Domestic Display of U.S. Presidents, manuscript in progress. ↵

- This is my conclusion from my extensive research into published photographs of interiors, as well as archived family photography collections. ↵

- Jennifer Wingate, “Framing Race in Personal and Political Spaces: New Deal Photographs of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Portraits in Domestic Settings,” Winterthur Portfolio (Summer/Fall 2018): 137–67. ↵

- Tevi Troy, What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House (Washington, DC: Regnery History, 2013), 139. ↵

- Elizabeth Ferrer, foreword, in The New Frontier: Art and Television; 1960–65, by John Alan Farmer (Austin, TX: Austin Museum of Art, 2000), 11. See also “America’s Long Vigil,” TV Guide, January 25–31, 1964, cited in Farmer, “Pop People,” in New Frontier, 56. ↵

- Ferrer, foreword, New Frontier, 10–11. ↵

- Witkovsky, “When the Earth Was Square,” 230. ↵

- Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, “Introduction: Photographs as Objects,” in Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images, ed. Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart (New York: Routledge, 2004), 12–13. ↵

- Coffey, “Louis Carlos Bernal’s Barrios,” 1. ↵

- The photo is located in AG 182 in the Louis Carlos Bernal Archive, 1953–93, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ (hereafter Bernal Archive). In other images, she and her husband hold the framed photo between them. ↵

- Richard Powell, “Lamentations from the ‘Hood,” in Kerry James Marshall: Mementos (Chicago: Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, 1998), 33. ↵

- Coffey, “Louis Carlos Bernal’s Barrios,” 4, 14, 34. ↵

- AG 182, Bernal Archive. ↵

- Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling, Home (New York: Routledge, 2006), 2. ↵

- Amalia Mesa-Bains, “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquachismo,” in Chicano and Chicana Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Jennifer A. Gonzalez, C. Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega, and Terezita Romo (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 91–99. ↵

- AG 182: 12/7, Bernal Archive. ↵

- There is less professional output within which to contextualize his photographs of TVs, especially compared with Friedlander’s copious body of work, which has helped scholars interpret his Little Screens series of 1961–70. Bernal was on the art faculty and head of the photography program at Pima Community College in Tucson from 1972 until 1989, when he was hit by a car riding his bike to campus. He remained in a coma until his death in 1993, on his fifty-second birthday. ↵

- Spigel, TV Snapshots, 96–98. ↵

- AG 182: 12/5, Bernal Archive. ↵

- I did not see the original photomontage, but a photographic print of the original is among Bernal’s papers. It features other imagery as well, including a photograph of a marionette. ↵

- AG 182: 12/7, Bernal Archive. The contact sheets for the presidential campaign and strikers’ portraits happen to be in the same file, labeled “contact sheets with no matching negative number, n.d.” ↵

- Enyeart, untitled essay, Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios, 13. ↵

- Enyeart, untitled essay, Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios, 13. ↵

- Mesa-Bains, “Domesticana,” 91–99. ↵

- Tomás Ybarrao-Frausto, “Rasquachismo: A Chicano Sensibility,” in Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965–1985, ed. Richard Griswold Del Castillo, Teresa McKenna, and Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano (Los Angeles: Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1991). ↵

- Spigel observes in her collection of snapshots that it was customary to place newer, more streamlined TVs on top of older models that had sentimental value or simply had become a familiar part of the household; TV Snapshots, 49. ↵

- These tapestries appear in several of Bernal’s Barrios photographs and in a number of Lee Friedlander photos as well. See, for example, photographs featured in Lee Friedlander: JFK; A Photographic Memoir (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 18, 21, 29, 31. One is also displayed on the wall in a 1967 photo by Marion Palfi of a family being interviewed by a social worker (collection of the Center for Creative Photography, 83.110.50). ↵

- Regular Spanish language television did not come to Arizona until 1979. ↵

- Enyeart, untitled essay, Louis Carlos Bernal: Barrios, 13. ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer Wingate is Professor of Fine Arts, St. Francis College.