More Than a Museum: The Chinati Foundation, Home of the Brave

PDF: Tolleson, More than a Museum

No one ever told me how to find Casa de los Valientes (1994; fig. 1). I first stumbled on the outdoor installation, also referred to as “The Wall,” in 2015 after I was brought on as a development intern at the Chinati Foundation. Once my office work was finished each day at 5 p.m., I was allowed to roam the museum grounds at will, and that is how I eventually found the work. Chinati is a sprawling campus that includes thirty-four historical buildings, most of which are located at the southern city limits of Marfa, Texas. A wire fence marks the perimeter of Chinati’s 340-acre property, where the museum’s founder, the artist Donald Judd (1928–1994), transformed a defunct military base into a contemporary art museum. Alongside site-specific installations, eight apartment buildings house employees, visiting artists, and interns. A dirt maintenance road connects the entrance of the museum to the rest of the grounds, and at a certain point, it becomes off-limits to visitors (fig. 2). But if you venture “off map” and follow the road south as far as it will go, you will find an isolated brick wall on a slightly elevated hill. Only fifty-eight feet across, this wall is easily traversed and seems redundant when compared to the barbed-wire fence only twenty feet beyond.1 You might start to wonder: if this is a work of art, why is it so hard to find, and why is it absent from official maps of the collection?

Casa was built by Anders Krüger (b. 1960), an artist-in-residence visiting from Denmark in the fall of 1994, ten months after Judd’s death, which meant the work could never receive Judd’s official approval for inclusion in the permanent collection.2 Yet it has remained hidden and inaccessible, seen only by the few museum employees and their guests who venture out into the desert, because, according to Chinati’s former senior advisor Rob Weiner, “it’s far enough out of the way that there’s no need to tear it down.”3 Excluded from the collection, Casa offers a critique of the very act of exclusion. Casa is thematically concerned with the formation and transcendence of boundaries and engages the identity politics of migration specific to this region of Far West Texas. Casa’s allusion to the Big Bend region and its location at the southern edge of Chinati’s campus implies that its intended audience inhabits and speaks the languages of these borderlands. Casa has elements that make it a close relative of Judd’s art at Chinati, but it addresses the history of the site and the subjectivity of its visitors in ways Judd’s works do not. The sculpture’s form offers a model for understanding the site as a homeland for both works of art and specific groups of people, and its title—which translates to “Home of the Brave”—calls on viewers to ask who the brave ones are that call this place home.

By making Casa, a virtually unknown artwork at the periphery of the museum, my point of departure, I aim to discuss Chinati with what decolonial theorist Walter Mignolo calls “an other logic” that changes the terms, not just the content, of the conversation.4 Casa, as this essay will elaborate, makes “border thinking” at Chinati possible because it alludes to Chinati’s participation in power relations and different local histories—involving migration, both from within and outside the United States, as well as the impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on both sides of the US-Mexico border. This essay speaks from the border, not about it, which, as Mignolo writes, makes border thinking performative, enactive, and ultimately transformational.5 Shifting the locus of epistemic knowledge to the borders (both of Far West Texas and of the Chinati Foundation) creates an opportunity to uncover new approaches to history that lie outside the framework of universal conceptual genealogies.6 Mignolo argues that the modern foundation of knowledge is territorial and imperial, and epistemic frontiers were traced by the creation of imperial and colonial difference, hierarchical binary divisions that relegated non-Western knowledge to an inferior status. But border thinking proposes a different epistemology that makes the border a site of negotiation and resistance, where the geo- and body-politics of local histories and embodied perspectives can deconstruct hegemonic orders. At Chinati, a museum that purports to display situations in which art, architecture, and landscape are inextricably linked, we can consider people as well. When the Spanish first encountered the region of the Big Bend, they called it el despoblado—the unpopulated land—which, as a colonial strategy, prepared the land for conquest despite the presence of Indigenous peoples, including the Chisos and the Jumanos.7 By thinking of Chinati as inextricably linked historically, socially, and economically to the city of Marfa and the greater Big Bend region as a site where people live and have lived, this inquiry expands beyond the art museum’s gate.

The Chinati Foundation is located at a crossroads; Judd wanted people to know this. In 1987, Judd published a “Statement for the Chinati Foundation” in The Chinati Foundation / La Fundación Chinati (fig. 3), a book of photos and drawings that document artworks and installations at the site, including Judd’s outdoor works in concrete and others still in development. At this time, Chinati became free of the influence of the Dia Art Foundation, which had financially supported the creation of the foundation (initially called “The Marfa Project”), and Judd seized the opportunity to announce to the world that Chinati would reflect his values. Judd’s “Statement” begins by telling the reader a story of how he became a resident of Marfa and made this place not only a site of his artistic development but a home for his family, his art, and himself: “In November 1971 I came to Marfa, Texas, to make a home for the summers in the Southwest of the United States and the Northwest of Mexico, which before the Conquest was called Chichimeca.”8 By referring to Marfa as not only a part of Texas but also as Mexico and preconquest Chichimeca, Judd locates his reader in an interstitial zone where temporal, international, and cultural differences rub shoulders and overlap. Deterritorialization is a theme that runs throughout the “Statement,” as Judd argues for the need to integrate all the arts and embed them more meaningfully within society. Judd quotes at length, in both Spanish and English, José Ortega y Gasset’s lament that art has become a “grace or jewel that man is to add to his life,” something separate and fragmented that appears optional rather than essential.9 As Judd explains, his goal is to rejoin these broken fragments, to insist that experiencing art be natural and ordinary rather than a privilege. Gradually and informally at first, Judd developed Chinati as a place where such experiences could be perceived.

Judd’s “Statement” outlines his primary objective in founding Chinati: to preserve in perpetuity works of art that are made for their existing context and to make sure the relationship between art, architecture, and landscape is cohesive.10 Judd believed permanent installations challenged the capitalist imperative to make all things, but especially art, property that can be purchased and traded, because permanently installed art could not be “conquered,” as he called an artwork’s dislocation from its place of origin.11 Although Judd continued to make art that could be collected by others, for him, the Chinati Foundation would become an alternative and ideal museum, an example of how art should be installed everywhere.12 Today, the institution houses permanent installations made by thirteen different artists, which, to varying degrees, have been integrated into the site and engage with either the surrounding environment or the renovated historic building in which they are housed.13

Because Chinati is designed to foster the integration of art, architecture, and landscape, it can inspire an immense scope of artistic experiences, leaving the boundaries between art and daily life difficult to discern. At Marfa, Judd refurbished existing buildings, transforming, for example, a facility for processing wool and mohair into the John Chamberlain building. The building’s footprint remains largely unchanged, but Judd made careful alterations to the space that complement its twenty-two Chamberlain sculptures made of painted and chromium-plated steel. Another of Judd’s curatorial decisions that contributes to a sense of disorientation is the lack of didactics to explain the works. Ostensibly, this choice was to encourage a more direct experience, avoiding preconceived notions about art. However, this practice can also lead to a productive (or disruptive) confusion about where the art and foundation end and the rest of Marfa begins. A third decision that blurs boundaries even further is Judd’s desire that spaces with art be livable, and thus visitors to the foundation are never far from a bed, kitchen, or even entire apartment, as eight separate living units are maintained at the foundation. In this way, Chinati can look like someone’s private dwelling, and the visitor can feel like a guest in someone’s (presumably Judd’s) house. In contrast to the temporary blockbuster exhibitions of objects carefully labeled by a curator, which were a mainstay of modern and contemporary art museums at the time, Judd sought to carve out a space where art objects are a part of daily life and the natural environment rather than existing in a separate sphere. As Judd writes in his “Statement”: “Art and architecture—all the arts—do not have to exist in isolation as they do now. This fault is very much a key to the present society. Architecture is nearly gone, but it, art, all of the arts, in fact all parts of the society, have to be rejoined, and joined more than they have ever been.”14 As a result of Judd’s integrated installations at Chinati, both art and daily life merged in transformative ways.

While Judd focuses in his “Statement” on the foundation’s future artworks and the importance of good installation, he says little about the role the foundation will play in Marfa, even though Chinati’s installations incorporate the town. Before Judd migrated from New York to Marfa, the town had struggled to recover from the great drought of 1949–56 that had decimated the ranching industry, which was, for many decades, a source of Marfa’s economic stability. By the 1980s, Judd had become a major local employer.15 As West Texas historian Lonn Taylor argues, “Art saved Marfa from oblivion”; artists came to make work, and curious global art enthusiasts came to see Judd’s work and, as a byproduct, spend money in Marfa.16 Sterry Butcher describes how “Judd put an art museum of permanent work in an isolated, poverty-stricken, hard-to-access town set in a landscape of tremendous, austere, and untamable beauty.”17 This combination ultimately made Marfa an art-tourism destination, with thousands of people visiting the town annually. Whether or not art “saved” Marfa, as Taylor suggests, it nevertheless has unmistakably transformed the town.

Although Judd hoped to unite the arts with society and may have believed Chinati could do so, existing physical, cultural, and artistic boundaries isolated the museum from the community. Interviews with longtime community members testify to a new type of order Judd enforced, both through the erection of walls or fences to mark property lines and discourage movement through informal pathways, and through the perceived elitism of Judd himself and the predominantly abstract art he installed. Marianne Stockebrand—a collaborator of Judd’s since the 1980s and a former director of the Chinati Foundation who published the foundation’s first official catalogue, Chinati: The Vision of Donald Judd (2010)—writes, “With the Chinati Foundation, Judd created a place where art can be viewed without distraction. Entering the grounds, one is transported to another world.”18 Judd had attempted, since the 1960s, to limit the scope of his work’s interpretation by insisting that its meaning remain “local” to its material facts, and a significant amount of scholarship on Judd, including on his work at Chinati, has hewed close to the artist’s intentions. In doing so, however, scholars run the risk of missing ways in which the artworks at Chinati have also always been historically complex, socially constituted, and entangled in an expansive environmental context. Nonetheless, Marfa and the subjectivity of those who visit, live, and work there play an important role in how Chinati is experienced. Revisionist scholarship on Minimalism—an artistic movement with which Judd is frequently associated—has attempted to “populate” what were previously considered the “abstract,” “empty,” or “neutral” spaces of Minimalist objects with embodied perspectives. In so doing, these studies bring to the fore the politics of perception and the power dynamics present in the shared spaces of contemporary art.19 This essay similarly seeks to frame Chinati as a crossroads of intersecting actors and histories that overlay and intersect with the wider environs of Marfa.

Although visitors to Chinati come to view works of art, Chinati also brings into focus Marfa’s ecological, cultural, and historical attributes, all of which contribute to the broader understanding of what contemporary art might mean. By exposing how the site of the Chinati Foundation has functioned throughout its history as a home for both people and art, this essay links Chinati to the stories of the Big Bend, stories that are as much a part of Chinati’s history as the artists who installed works there.20

Casa de los Valientes

No image of Casa exists in Chinati’s catalogue, on its website, or within any map of its collection, but Casa has quietly persisted at the edge of Chinati’s campus since 1994. Casa is present but not officially acknowledged; it occupies a liminal position in relation to the permanent collection. In this way, Casa offers an oblique vantage point from which to study Chinati’s boundaries and the museum’s relation to Marfa. Chinati’s “official” narratives typically place Judd at the center; by comparison, Casa tells an “unofficial” story about Chinati and specifically the land on which it was founded, a story that offers a productive counterpoint. By starting with Casa, we can expand the narrative to encompass the broader border region.

Made of red bricks with the word “Mexico” baked into each one (fig. 4), Casa alludes to the sixty-seven miles separating Marfa from the US-Mexico border. The wall is not entirely uniform, with a passageway and a viewing station. The passageway on the western side of the sculpture is wide enough for one body to walk through, while the viewing space on the eastern side is shaped by the wall dropping down to the height of three feet from its otherwise consistent five-and-a-half feet. Casa is oriented along an east-west axis and located not only at the southernmost edge of Chinati’s campus but also at the southernmost edge of Marfa. Beyond Casa, one sees open sky, faraway mountains, and largely undeveloped desert, most of which includes thousands of acres of privately owned ranch land between Chinati and the border towns of Presidio, Texas, and Ojinaga, Chihuahua.

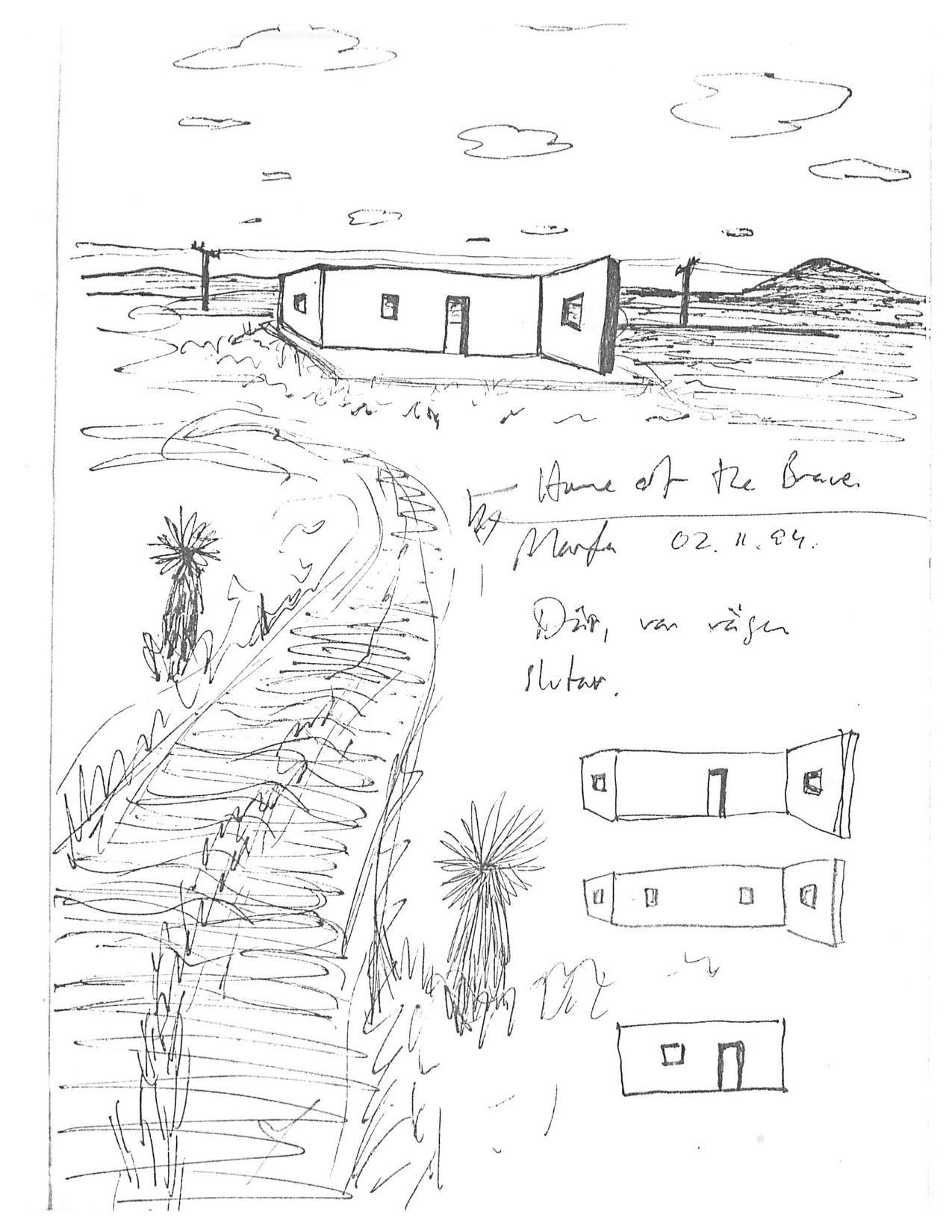

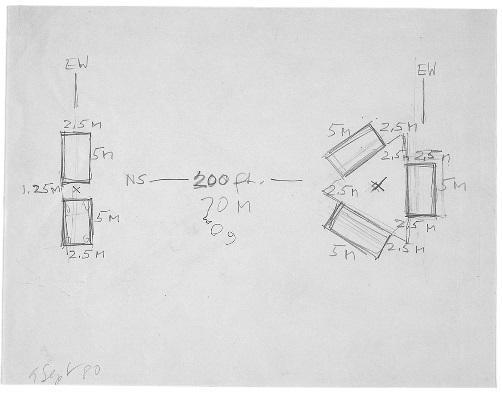

Casa appears like a boundary between Mexico and Marfa, and it resembles the façade of a home one could potentially inhabit. Krüger emphasizes this latter interpretation by referring to his sculpture as a house made with the most minimal of means.21 A preliminary sketch (fig. 5) demonstrates how the concept began with three walls, which Krüger reduced over time to one. As the façade of what one might call a very open house plan, Casa points to the fact that Chinati has always served as a primary residence. Directors of the foundation have resided on the grounds.22 In addition, Chinati has housed interns, employees, and visiting artists like Krüger himself. But Casa’s openness also extends to the city of Marfa and reminds visitors how Marfa serves as a rest stop for border crossers and tourists and as a home for generations of Indigenous communities, Texans, and transplants. While the Spanish word casa is typically used to indicate a house and hogar is used to indicate a home, Krüger’s title invokes both meanings by poetically referring to the US national anthem in Spanish. The integration of languages and meanings foregrounds the artwork’s hybridity and suggests that the borderlands of Far West Texas represent a place where many different groups of people have settled and intermixed.

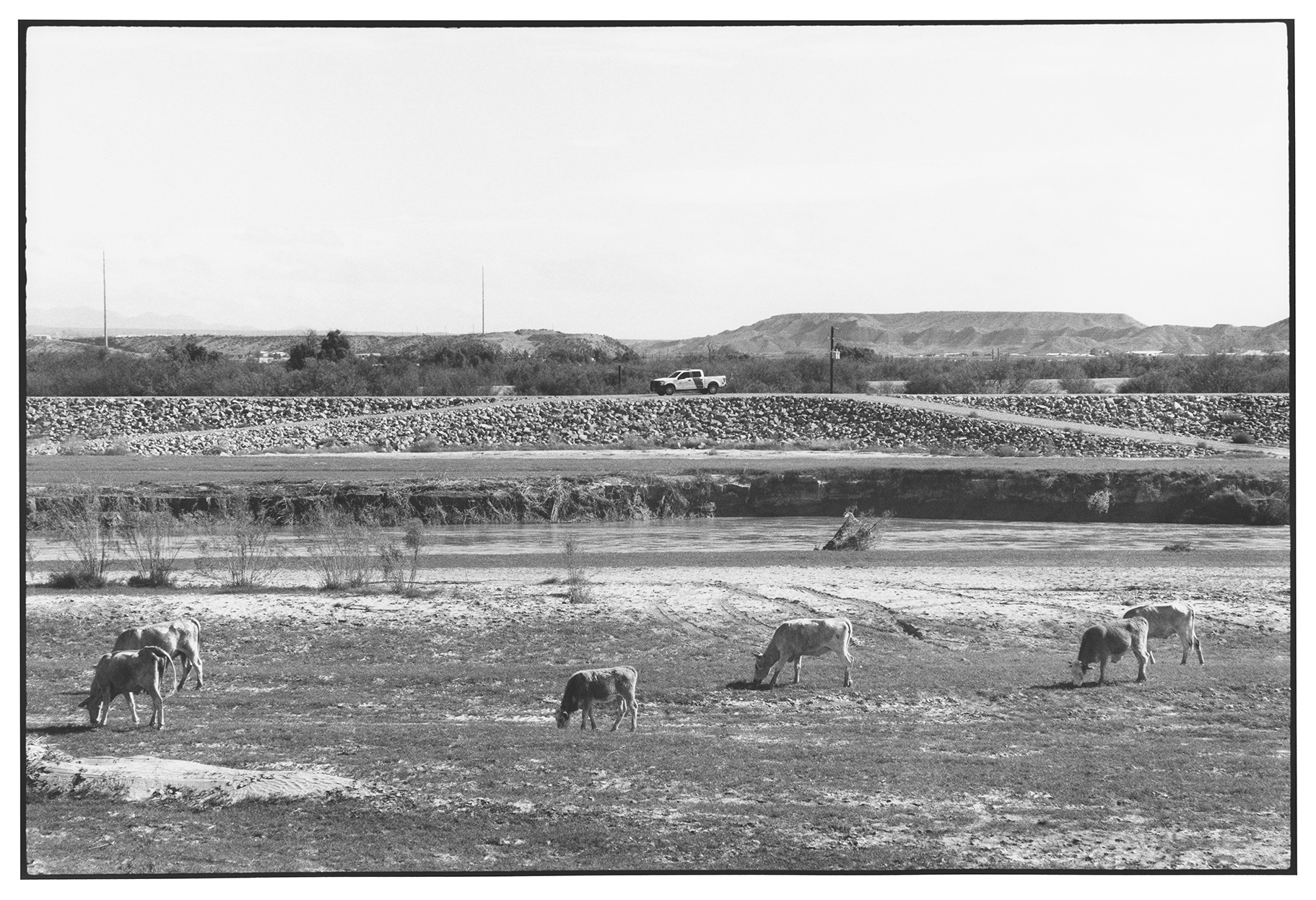

By including the word “Mexico” on each brick—a likely indication that the bricks were made in Mexico—Casa reminds visitors that this part of Texas was once Mexico and that some may still consider it as such. Casa can also be read as a wall—a physical shorthand for the boundary that marks the US-Mexico border sixty-seven miles south of Krüger’s sculpture.23 At the nearest border junction, the Rio Grande, known in Mexico as the Río Bravo, acts as a vernacular boundary—natural and crafted at the same time—which, as it twists and turns, divides Presidio from Ojinaga and splits the United States and Mexico into northern and southern territories (fig. 6). But the wall at Chinati is hardly enforceable; it is more of a provocation than a barrier. Not only can visitors easily walk around it, but they can also walk through it (figs. 7, 8). Viewers can stand on either side of the wall or within it; in parallel, they can imagine themselves positioned on either the Mexico or US side, or both simultaneously. Casa defies our understanding of a boundary because it is easily traversed; similarly, it defies our understanding of a house because it offers hardly any protection from its surroundings. But in its openness and permeability, Casa asks us to think of the place it occupies as a crossroads and a homeland for myriad groups of people.

Casa was built by Krüger in the fall of 1994. Chinati’s program to invite artists to make work while living at the museum began when Judd was still alive. In 1982, he invited his longtime friend John Wesley (1928–2022) to work at Marfa; later, Wesley was acknowledged as the museum’s first artist-in-residence.24 After Wesley, the museum regularly hosted between one and twelve artists a year, often from European countries; Krüger was one of them. Works by certain artists-in-residence, like Ingólfur Arnarsson (b. 1956), who visited in 1992, became part of the permanent collection. However, once Judd died in February 1994, visiting artists’ work was only installed temporarily, because Judd was no longer alive to potentially sanction its inclusion in the permanent collection. It is therefore unusual that Krüger’s Casa was not dismantled.25 Neither part of the permanent collection nor a temporary installation, this work remains a

unique outlier.

Casa is also a transitional work within the artist’s development. Krüger was still an emerging artist when he did his residency at Chinati, and the scale and breadth of his work grew after his time in Marfa.26 Krüger received his Master’s in Fine Arts in sculpture from the Royal Danish Academy of Art in 1991 and went on to take a postgraduate course in architecture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm, in 2004. Krüger’s website describes Casa as “sculpture with architectural ambitions.” Work Krüger made before and after his residency in Marfa indicates that Casa propelled him toward public sculpture.27 While many of Krüger’s early sculptures like Twin Sculpture Venus Genetrix (1989) and Rosa (1991) appear portable or require pedestals, after Casa, Krüger developed large-scale public installations.28 An example is Terra Incognita (2014–16; fig. 9), a memorial to the Norway terror attacks of 2011 that Krüger designed in collaboration with the architect Marianne Levinsen (b. 1963). The sculpture, which is made of concrete islands, includes texts that refer to the events of July 22 in Oslo but also “function as mental bridges to a poetic and creative dimension of reality.”29 The memorial physically manifests its creative connective potential by doubling as a platform on which visitors can stand or perform.

Like Terra Incognita, Casa also deploys language to poetic effect and is an interactive sculpture that allows visitors to have a phenomenological sense of the landscape and its history. Krüger writes that Casa “contain[s] nothing without being empty” because the landscape inhabits it.30 However, its title, Casa de los Valientes (Home of the brave ones), poetically alludes to the history of migration to Marfa, specifically cross-border migration from Mexico. As visitors experience both sides of the wall, they can contemplate the words “Mexico” and “Home of the Brave” and consider, in an embodied way, what it might mean to call this place home and who might live there.

By referring to the US national anthem in Spanish, Krüger’s title evokes other revolutions, other homes, and other forms of bravery. Perhaps Judd is the brave one, who struggled for independence from the art world and eventually turned his back on New York to make Marfa his home. Or maybe the title alludes to the tourists who cross vast stretches of desert to trek to Marfa and see Judd’s foundation. A third possibility is that the non-English title addresses native Spanish speakers as its primary audience. The sculpture’s orientation to the south and its seemingly Mexican-made bricks direct attention on Mexico. When approaching Marfa from the Mexican border, sixty-seven miles away, Casa is possibly the first landmark one sees, perched on a hillside to the left of Highway 67, as they enter the city limits (fig. 10). Even though it stands at the border of Chinati’s fenced perimeter, the artwork seems to address a traveler approaching from Mexico to the south.

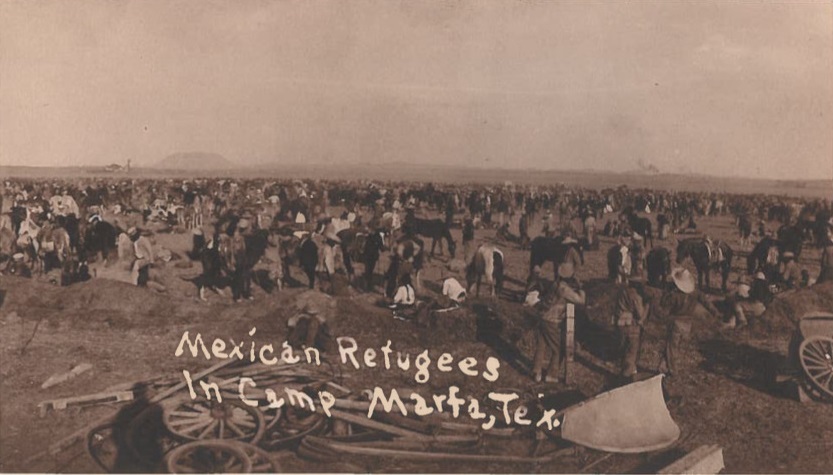

Casa responds to the histories of border crossing, especially for locals aware of Marfa’s history. More than one hundred years ago, Marfa and the land where Chinati is located became a home for Mexican refugees, some of whom never left. In 1883, after a sustained period of westward expansion and US military attempts to displace the Jumano, Apache, Comanche, and other tribes who inhabited the region, Marfa was incorporated and served as a military town.31 Due to incessant raids on both sides of the border by Pancho Villa during the lead-up to the Mexican revolution, Camp Marfa (first located at the site of Fort D. A. Russell, now the Chinati Foundation) was established in 1911 to police the region. It eventually became the headquarters of the US Customs and Border Patrol for the Big Bend Sector, which, since 1977, has shared a fence with Chinati’s property. Pancho Villa’s 1913 raid on the border town of Ojinaga essentially transformed Marfa overnight. Villa’s raid caused thousands of Mexican citizens to flee across the border for help. These refugees walked or rode horseback, under US military escort, sixty-seven miles north to Marfa along what is today Highway 67. Many took shelter at Marfa and eventually made it their home (fig. 11). As Taylor explains, “The census records tell the story.”32 In 1910, 30 percent of the population of Marfa was born in Mexico; in 1920, the figure was 74 percent. By 2018, Marfa had about 1,700 inhabitants and was 68 percent Hispanic. Villa’s raids significantly impacted Marfa’s history by transforming Marfa into a majority Hispanic community that has remained majority Hispanic more than one hundred years later.

Krüger’s Casa evokes these histories of migration by allowing visitors to view both sides of the wall and by creating a third space that is between the land to the north and south. Although Casa divides the landscape in two, it also dissolves this division by remaining a crossable boundary. The rectangular concrete base of the sculpture, on which the bricks are laid, notifies the visitor that they are standing in an interstitial zone that encompasses both sides of the border. We must remember, however, that engaging in Casa’s performative symbolism is not directly equivalent to standing on both sides of the Rio Grande/ Río Bravo. Krüger was a temporary European resident at Chinati who made a work of art that exists for and within the art-tourism economy. For border crossers, this land provides a life-giving respite. The stakes are very different, and there is what Mignolo calls an “irreducible difference” to the experiences and discourses in operation here. But the key to “border thinking” is “thinking from dichotomous concepts rather than ordering the world in dichotomies.”33 Casa makes visible the relationship between Hispanic/ Anglo, Mexico/ United States, and Spanish/ English, situating them as overlapping rather than oppositional terms that remain distinct yet connected. Gloria Anzaldúa, a leading borderlands theorist writing from an embedded position, argues that borderlands are hybrid places at their core and form a third space between cultures and social systems, in which antithetical elements mix.34 Those who inhabit borderlands, she writes, live between two countries, two languages, and two cultures, which produces an awareness of the contingent nature of social relationships and the constructed nature of social categories.35 Casa, I suggest, exists in the hybrid space Anzaldúa describes, a space in which different histories converge and new forms of consciousness emerge.

Casa was erected in 1994, the same year as parts of NAFTA went into effect. As such, the border was taking on a new political valence. Designed ostensibly to promote low-tariff trade between the United States, Mexico, and Canada, the agreement allowed market penetration and investment in Mexico, the relocation of production, and the creation of new supply chains. US companies were incentivized to make their products in Mexico, where labor was relatively inexpensive, and then import those goods back into the United States, resulting in domestic job losses. At the same time, the Mexican market could not compete with subsidized US farm goods, like corn, leading the country to largely import rather than produce certain staple products domestically.36 In NAFTA’s first year, one million Mexicans lost their jobs, creating vast numbers of displaced people who then became the workforce for maquiladoras located along the border or who migrated to the United States.37 As David Bacon describes them, maquiladoras are typically foreign-owned manufacturing companies that tightly control workers, pay low wages, and suppress unionization.38 Describing the choice between working for the maquiladoras or migrating, Anzaldúa writes, “for many mexicanos del otro lado, the choice is to stay in Mexico and starve or move north and live.”39 Read in this historical context, Casa’s “Mexico” bricks become a sign of outsourced labor that encapsulates the kind of newly formed US-Mexico relations that took place under NAFTA.

But Krüger did not buy his bricks from a maquiladora. When Krüger arrived at Chinati, he found five stacks of bricks at the southern edge of the campus (fig. 12). When he asked then director Stockebrand how they got there, she said she thought they had been left by Judd.40 In typical Judd-like fashion, Krüger decided to work with what was “given,” building on Judd’s unknown and unfinished project. But he could not have done so without the skills of local laborers (fig. 13). As Krüger describes:

I got a crash-course in masonry by José—a local mason in Marfa. I had gone to The Sports Bar, asking if anybody knew of a mason in town. They directed me to a house a couple of blocks down the street, where José was working. I introduced myself and presented my project, asking if I could hire him to teach me how to do masonry. He said “Sure,” I asked when he would have time, and he replied, “How about right now?” So, he dropped his tools, and we drove out to the site. The next day I brought the necessary materials—sand, cement, a wheelbarrow and an oil-barrel full of water with Chinati´s old Chevy pick-up truck, and he taught me the basics of masonry. He proudly refused to take any money. I worked every day, from early mornings till late, cold and starry December nights, in the headlights from the Chevy (it was an amazing place to star-gaze from). I had come to the bottom of the window-opening when I realized I was not going to make it in time for my return to Copenhagen. One of the next days I received notice I had gotten a grant from a Danish foundation. With that grant I could hire two masons to help me finish the work—two guys that previously had done work for the Chinati: Chuck [Barker] and Jesús [“Chuy” Licon]. They were very skilled, and the three of us together got the job done just in time for my departure.41

Using the printing press at the Big Bend Sentinel, Krüger produced a poster to announce the completion of his sculpture. The central image appears to be a life-size charcoal rubbing of one of the bricks (fig. 14), with the word “Mexico” faintly legible. Krüger’s indexical tracing of a brick for the poster becomes another sign of labor and suggests the cross-border journey each brick traveled to arrive in Marfa and eventually become part of Casa de los Valientes. By referencing this mobility, Krüger’s Casa encourages us to consider the idea of home less as a building one can step inside and more like a zone one moves to and through, a space brought to life through movement.

The Chinati Foundation has always served as a home as well as a museum and work area. Judd placed beds in certain exhibition spaces and maintained apartments for guests and employees so that they could have a place to rest after making the journey. After all, Marfa is a small town nearly 190 miles from a commercial airport. The residential quarters are a practical necessity, but they also contribute to Chinati’s immersive experience. In 1987, Judd also began the annual tradition of serving free communal dinners for friends and neighbors in Chinati’s Arena, calling it Chinati’s “Open House.”42 Krüger’s Casa deftly alludes to the history of the site as a meeting ground, shelter, or rest stop for tourists, locals, Chinati workers, and immigrants alike. As a “sculpture with architectural ambitions,” it fits within Judd’s own goal for Chinati to be a museum where one can live with works of art. Casa’s openness and conceptual looseness reflects Judd’s own interest in making works that are accessible and rich in potential. But Krüger’s Casa differs from other works at Chinati because it encourages the viewer to imagine not only the history of migration at the site but the markers of identity that distinguish different visitors.

One irony of Krüger’s very open plan is that it is fenced in on all sides. This has contributed to its obscurity and erasure from public knowledge. A visitor approaching Chinati through its main entrance will need a certain amount of privilege (in terms of access and knowledge) to see Casa up close. Those who lived or worked at Chinati between 1994 and today may have encountered Casa, but most members of the public have not. Due to its particular peripheral location, Casa sets up a dynamic in which visitors are able to sense their own privilege or lack of it when approaching the work; its placement unsettles any understanding of Chinati’s desert landscape as a neutral or abstract space. Krüger explained that Casa’s location essentially selected itself: the bricks and concrete base were already there when he found them, remnants of an unknown and unfinished project of Judd’s that Krüger put to new purpose. Krüger could not have known when he built Casa that it would ultimately reap a particular benefit from its location: because it was built “far enough out of the way,” invisible to almost everyone, its presence was and remains tolerated by the museum. Judd designed Chinati to be a place where artists could make their work freely, unencumbered by institutional oversight. But with its peripheral location, Casa reveals something important about the cost of freedom and the ways in which structures of privatization, like fencing, go hand in hand with value systems that prize independence. Unknown to the public and officially unacknowledged by the museum, Casa has never been conserved, and today grasses grow through its concrete base, which is cracked across its surface; the nearby bench, originally installed in 1994, is unusable (fig. 15). Casa’s relationship to the land, both historically and spatially, is unique compared to other works on campus, and it thus functions as a counterpoint to Judd’s interventions.

Life between the Blocks

Whereas Krüger’s Casa confronts the land as a marked site, Judd’s 15 untitled works in concrete (1980–84; fig. 16) appear indifferent to the landscape around them. The artwork is comprised of fifteen configurations of hollow objects, all of the same exterior dimensions (2.5 by 2.5 by 5 meters) that form a row measuring almost exactly one kilometer.43 As abstract blocks repeated in different configurations, Judd’s works in concrete form a modular system that refers only to itself. Nonetheless, there is a site-conditional and open quality to the works. As with Casa, the land determined the artwork’s position. Judd scaled his design to fit proportionally between a property line on the north side of a field and a naturally occurring hill that rises to the south. The blocks appear with infinite variations, since the sun casts them with ever-changing shadows (fig. 17), and viewers must move around them to fully take in the installation. Many of the blocks frame the landscape, creating an experience in which the military buildings, native grasses, and viewers become part of a living artwork, grounded in its present moment. The experience of the sculpture involves subtle motion, like a tableau vivant.

The concrete works direct our attention to the natural phenomena of the site as well as local landmarks but offer little interpretive guidance. Judd deliberately untitled the work and referred to it only as “15 works in concrete,” which can be seen as a universalist gesture of neutrality, reinforcing the idea that somehow the facticity of the object wipes the concrete clean of any historical or contextual relationships. Clearly outward facing, these works also seem reticent to engage the environment or subjectivity of those who encounter them, despite the mutability I have described in their perception. At times, the viewer may even glimpse a sense of the sublime when looking through the blocks at the seemingly endless landscape. The warmth and light effects produced by the sun constitute part of the experience of the work and, like Krüger’s Casa, the viewer’s body can enter the framework of the piece. In this way, the audience realizes there is no “outside” position from which to view the work and its situation. But the landscape is not endless, and it is, in fact, broken up by the built environment. Highway 67 runs by within earshot; the border-patrol parking lot with vehicles for transporting migrants can be seen next door; and Chinati’s repurposed military buildings dot the horizon. Each visible landmark infringes on a “pure” experience of Judd’s concrete works and situates Chinati and its installations within the borderlands of Marfa.

The ostensible neutrality of the concrete sculpture is difficult to square with Judd’s purported mission to join art with society. In fact, Judd attempted to limit the extent to which his art was perceived as a part of any larger social organism. Judd used the term “local order” to describe the arrangement of certain objects he made, particularly his early works, as a way to deflect grandiose interpretations, including ones that implicated his persona.44 This may also have been a reaction to Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), whom Judd succeeded generationally and whose work was codified by critics as representative of private and personal expressions that Judd rejected.45 For Judd, geometry, mathematics, proportion, and scale were democratic tools that, when applied to art, gave the work a specific relation to space and time that had nothing to do with the artist’s biography. Judd’s attempt to build works of art that were like objective facts conveyed an anarchistic impulse to liberate his work from specific meanings and metaphors.46 This notion is apparent in Judd’s drawings for the concrete works (fig. 18), in which the objects appear to float in space from a bird’s-eye view. The forms exist only in relation to each other. In Krüger’s sketch for his sculpture, on the other hand, Casa exists in the world (see fig. 5). The drawing includes cacti, clouds, electricity wires, and a trail, detailing a specific embodied perspective. This comparison allows us to surmise that Judd’s works in concrete refer primarily to one another and only secondarily to the landscape surrounding them, an environment Judd did not design and accepts as given. This conclusion is only true, however, if we approach Judd as an artist. As an institution builder, Judd exercised substantially more control over his work’s context, and it is important to view both types of construction as coconstitutive.

Rather than think of the landscape around artworks as a noun—as in “art + architecture + landscape”—what changes if we think of it as a verb? W. J. T. Mitchell poses this question in Landscape and Power, prompting us to consider how landscapes can often seem “given” or “natural,” or even as things in which we might “lose ourselves,” while, in fact, they work to naturalize a social construction that shapes us as much as we shape it.47 Judd was not the only artist associated with Minimalism who worked “in the land,” but the manner in which his Land art engages with and orients visitors toward Marfa deserves further examination. Art historians like Dawna Schuld and Jennifer Roberts have challenged accounts of Land art that do not consider how social dynamics and local history play a role both in the making of the works and in the ways they are perceived. While Krüger’s Casa overtly directs the visitor’s attention to ways in which the landscape has been divided into arbitrary territories, Judd’s concrete works more subtly destabilize any fixed notion of landscape as a finite and contained thing. Casa allows visitors to sense the politics of perception as they engage with the sculpture, and it serves as a model for bringing a similar political valence to our perception of Judd’s work at the Chinati Foundation, a place where art, architecture, landscape, and people are inextricably linked. My intervention in this section is to think through how landscape and the site in general is activated at Chinati, as well as how it is historically and spatially constituted by the actors who engage it.

One way Judd went about preparing the grounds for the concrete works was by making developments in the infrastructure that defined the landscape as part of an artistic experience. One rarely acknowledged example of this kind of supporting structure is the barbed-wire fence that Judd partially erected, which cordons off Fort D. A. Russell. For many years after the fort closed in 1946, it was largely accessible to anyone adventurous enough to explore the grounds. Sections were purchased from the military by private citizens, but the fort itself became, for the most part, a ruin.48 Ray Zubiate, who was born and raised in Marfa, recalls exploring the fort with his friends in the 1950s: “There were no gates. The fort was one big playground for us. That creek that runs through Chinati goes all the way up behind my house at the arroyo, and we would all take excursions [down the creek] and into the fort.” There Zubiate and his friends discovered army cots, potbelly stoves, brass cartridges, and even a .45 caliber pistol left over from its days as a military base.49 Until Judd and the Dia Art Foundation acquired the land in 1979, the former fort was sporadically leased by farmers, teachers, and tenants, but for the most part it was open land. By putting up a fence in 1981, as well as a gate and “No Trespassing” signs, Judd gave it definition as an art complex and, at the same time, declared it private property.50 Judd’s fence, alongside his other construction projects at the fort, became a sign that marked the land and everything within its perimeter as a charged zone of artistic experience.

Because the concrete works are abstract and frame their surroundings rather than refer to them metaphorically, Judd may be implying that what surrounds the concrete is beyond his intervention. Judd’s title and drawings certainly position the work in this way, as autonomous and distinct from its surroundings. Unlike Casa, which deconstructs Chinati’s fenced perimeter by embracing the region’s contiguous landscape, Judd’s concrete work appears at first glance as a closed system. But what about the space between and around the blocks, all that Judd did not construct, yet was certainly transformed by making an open field into an artistically charged zone? Just as the concrete work is conditioned by the natural environment, the environment is likewise conditioned by the work; everything within Chinati’s perimeter becomes imbued with an aura of intentionality even when not everything is a work of art. How, then, is our perception of something as commonplace as land, an apartment building, or a social situation changed once it has been designated part of the museum?

Consider the openings within the concrete works. The way they frame the landscape puts the viewer in control, as if they are behind the viewfinder of a camera. Conversely, the apertures also put the viewer on display as if they are in front of a camera. The boxy concrete structures create picture-book views that are at once three-dimensional and flat, real and illusionistic, instilling the viewer with uncertainty about the meaning and status of what is experienced (fig. 19). The works invite the audience to see themselves embedded in this landscape that extends far beyond the museum’s perimeter. At a human scale, the blocks could potentially be entered by the viewer, forming a makeshift shelter, and animals definitely climb inside when no one is around. But while the land, animals, and buildings provide a wider context for the works, everything inside the museum perimeter, including the visitor, is potentially altered by being located within an art complex. These outdoor sculptures exist within an evolving interactive situation, the boundaries of which are porous and exceed the objects’ material facts. Like Krüger’s Casa, which functions as an invitation to the viewer to become an active participant in a politicized landscape, Judd’s concrete works are catalysts for the viewer to become situated inside the built environment of his art museum and the town of Marfa. Due in no small part to the deployment of curatorial strategies, like the deliberate absence of didactics, Judd’s concrete works interpellate visitors within a particularly disorienting perceptual framework.51

While Judd’s work at Chinati raises important questions about situational artistic practice and how art after Minimalism has shaped the politics of perception, scholarship on Judd has tended to more frequently associate the artist with his sculptural innovations from earlier in his career.52 Yet, as art historian Rosalind Krauss argues, the art made by Judd and his peers could hardly be called sculpture.53 In the 1960s, Judd significantly expanded sculpture’s playing field by refusing the pedestal and making “specific objects” that forged a path beyond the pictorialism and illusionism associated with modernist art and into the real space of the viewer (fig. 20).54 As Edward Vazquez writes, “For artists like [Robert] Smithson, [Dan] Graham, and [Fred] Sandback, Judd’s objects prompted not only an interest in materials, but also a way of thinking through spatial engagement and developing modes of environmental viewership beyond the discrete object.”55 After the “specific object,” many artists began purposefully constructing situations as art, marking what some art historians have called the “phenomenological turn” in art history.56 But historians of this shift tend to exclude Judd, whose association with objecthood has overshadowed his later environmental interventions.57 While Judd did indeed explore such sculptural innovations, the emphasis on these achievements foregrounds discussions of Judd’s work in a particular mid-twentieth century moment that does not account for the broader social implications of his work in Marfa.58 Art historian Jennifer Roberts, in her study of Robert Smithson (1938–1973)—a contemporary of Judd who Roberts considers a transitional figure between modern and postmodern artistic practice—identifies a similar type of “historical foreshortening” when it comes to Smithson’s legacy.59 Roberts argues that Smithson’s site-specific art not only constituted a response to modernism but also importantly drew from a sense of place—be it Passaic, New Jersey, or Golden Spike National Park, Utah. By radically bringing local historical context to bear on Smithson’s Land art, Roberts presents a more comprehensive understanding of the artist’s engagement with specific sites and their histories. Similarly, our understanding of Judd is enhanced by attending to the specific contextual and historical circumstances of Marfa and Chinati.

An integrated account of Chinati would include a discussion of its artworks not only in dialogue with Marfa’s history but also in light of the viewing conditions Judd created there, which disturb any idea of the museum as a neutral space. Despite Judd’s insistence that the meaning of his works remain “local” to their material facts, his concrete works also lend themselves to “border thinking” in that they require the viewer to take an embodied and performative approach to Chinati and Marfa. “Border thinking” is arguably not unlike a historically constituted phenomenology, wherein one senses oneself at the border but relative to others and in relation to markers of identity that envelop individuals within larger social systems. Cristina Albu and Dawna Schuld write that phenomenological art, which incorporates the particularities of its environment, often relies on its very instability to be meaningful, challenging visitors to see themselves as entangled in local, biological, social, and historical processes all at once.60 In “Being Nowhere: Desert Situations,” Schuld writes that artists like Walter de Maria were attracted to the desert because it represented the opposite of the “white, empty, silent, gallery,” comprising instead a heterogenous and exposed space from which works of art can prompt new forms of awareness. But according to Schuld, the desert also represents an “irrational space” against which artists could install works that “frame” and “straighten” an otherwise “ragged” and “arbitrary” space.61 The desert, of course, is not equivalent to “nowhere,” and Judd’s concrete works act as conduits for seeing oneself embedded in a landscape that is populated by diverse communities and landmarks of a built environment, like the border-patrol headquarters that predate the museum’s founding. Krüger seemed to understand this about Judd’s work at Chinati when he built Casa. He built a sculpture that “contained nothing without being empty” by allowing the landscape and its diverse histories to inhabit it. Krüger’s and Judd’s works at Chinati embrace the destabilizing force of the surrounding environment in its complexity and acknowledge it as a crossroads for myriad travelers and inhabitants. Visitors to Chinati are exposed to the elements, as well as small-town life, without any explanatory didactics to delimit their experience. This ensures that the visitor’s encounter with the art is fused with an encounter of Marfa.

Art that engenders a phenomenological experience is assumed to foster introspection, but the reality is often far more dialectical. As the boundaries between the work of art and the lived experience of a viewer break down, the subject perceives themselves perceiving, which can be characterized as necessitating an asocial and personal inward turn, sometimes bordering on the solipsistic.62 Albu and Schuld argue that perceiving oneself perceiving, however, “openly concedes the likelihood that personal experience is only ever partial while at the same time resisting any notion of universal experience.” At sites like Chinati, visitors enter into a shared situation where they “encounter [their] own formation in an indefinite and interpersonal space.”63 The work of art, then, becomes collectively fulfilled through its contingent relationships. Underlying Albu and Schuld’s argument is the premise that viewers are never passive spectators but actively engaged participants in an unfolding and sometimes challenging process of negotiation between themselves and the artistic environment. Casa provides visitors with an infinite array of choices about how to interact with the sculpture, and, in so doing, the work prompts its viewers to consider both the range of people who have called this landscape home and their own identity relative to the border. Even Judd’s concrete works, which appear ostensibly “neutral,” facilitate situations in which visitors can see themselves relative to others. While phenomenological art can disrupt a viewer’s tendency to turn inward, the disorientation produced by this art also “serves as a cue for considering more imperceptible regulators of experience and the limits of individual agency.”64 When we consider Chinati’s landscape as a populated one, we can begin to think of the museum as a facilitator of challenging social interactions and asymmetrical power relations.

Where a work of art ends and daily life begins can be difficult to discern at Chinati, but confusion over the limits of artistic experience seems to be something Judd encouraged. He interpreted concepts that define, classify, and explain experience as detrimental barriers to empirical knowledge. At Chinati, part of the challenge is navigating so-called unmediated experience, which can feel at times as if anything a visitor encounters on the grounds is influenced by a heightened sense of artistic intentionality. By way of illustration, when I worked at Chinati as an intern in 2015, I lived in an apartment at the museum, just a few hundred feet from where I worked in the museum offices. Regularly scheduled guided tour groups would traverse the grounds most days of the week. One weekend morning, as I was eating breakfast in another intern’s apartment, a stranger suddenly appeared at the window, poking their head inside and looking around. They refused to believe we were merely eating a meal, asking “Is this an exhibition? . . . Is there art in here?” Finally convinced, they left to rejoin the tour group that was being led down the sidewalk outside the apartment. While I initially laughed at the bewildering encounter, the visitor’s questions were completely justified, because Judd made it purposefully difficult to know where art ends and daily life begins at Chinati. With no signage, interpretation can run amok, leading to confusion about the meaning and status of what is encountered. Considering that Judd designed Chinati as a place where art can be experienced as an ordinary component of daily life, it seems possible he may well have intended there to be moments when daily life was perceived as art.

Judd once wrote that “the categories of public and private mean nothing to me,” and at Chinati these distinctions can seem thoroughly dissolved.65 Judd was talking about how viewing art, which for many of us happens mainly in a museum context, can be both intensely private and public. All kinds of private feelings, questions, and vulnerabilities can rush to the surface in front of a work of art, and often we have this experience while surrounded by strangers. Yet most people do not live inside a museum. When I was confronted in my colleague’s apartment, I could not help but feel as though I had been put on display and that I needed to defend my right to eat scrambled eggs as a non-artistic endeavor. Many people, especially artists, have highlighted the sense of alienation and somber ambience that can accompany a typical museum visit; some have even compared museums to prison houses, asylums, or mausoleums.66 After all, the wall labels at museums are cynically called “tombstones” by museum workers. One reason Judd never wanted any “tombstones” at Chinati may have been to keep the art and our experience of it alive, in play, and in need of continuous renegotiation. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that by the end of his life, Judd stopped calling Chinati a museum.67 Judd wanted to make art a component of daily life, but at Chinati both art and life merge in volatile ways that challenge our assumptions about both.

The fact that Chinati is inextricably connected to its surroundings leads to a realization that the museum is not a world apart but a facilitator of challenging social interactions that affect the way visitors approach not just art but everyday situations, even after leaving the museum. Chinati’s land is marked by its histories of conquest, ownership, and use; space is never neutral but altered by those who embody it; and we are always political actors no matter what kind of actions we take. Casa engages with this meshwork of ideas. Consider the audience for Casa, which can only locate and examine the work with special privileges. Employees, interns, artists-in-residence—all “insiders” at one time or another—may eventually find Krüger’s sculpture, but tourists and townspeople may never know it exists. Someone without special access and insider status may only be able to glimpse the work by approaching Chinati from the south on Highway 67, albeit from a distance. Krüger’s sculpture becomes a valuable tool for invoking what Walter Mignolo and Madina Tlostanova call the geo- and body-politics of border theory.68 To approach Chinati from “below” and from multiple perspectives allows us to situate the museum at a crossroads of intersecting actors, cultures, and histories that participate in asymmetrical power relations. In doing so, we also complicate the museum’s “official” narrative, in which Judd occupies the center. Mignolo argues that scholars must speak from an embodied position and with an interdisciplinary approach to account for the cross-cultural terrain of borderlands. Roberts, Schuld, and Albu have separately argued that art historians must think across disciplines and acknowledge that spaces of contemporary art are shared in order to account for the situational contexts of minimal and phenomenological art. Although emerging out of separate discourses, the ideas they espouse offer a guide for understanding the complexity of a place like the Chinati Foundation.

The Museum after Minimalism

In conclusion, I offer again Mitchell’s aforementioned question, but this time reformulated: rather than think of the art museum as a noun (as in, for example, a repository of art objects or a tourist destination), what changes when we think of it as a verb? Chinati has always functioned like a home for works of art and a commune for extended visits at its site, but it has also contributed to Marfa’s transformation in both intentional and unintentional ways. Chinati’s former director Jenny Moore claimed that since she was hired in 2013, she did not purposefully set out to raise visitor attendance levels; nevertheless, annual attendance more than doubled in the subsequent years, rising from 22,889 visitors in 2014 to 49,111 visitors in 2019.69 The increase in visitors to Chinati (and, by extension, to Marfa) has, over time, indirectly led to a cascade of changes to the town that include an increase in the number of Marfa’s short-term rentals, hotels, and art galleries that cater to the transient population and a decrease in the stock of affordable housing options for residents.70 While Chinati is not the only reason visitors travel to Marfa, Moore believes that “Chinati has been the most significant agent of change [for Marfa] from the 1980s on . . . [and so] it is important for Chinati to be a good community partner.”71 As mentioned, since 1987, Chinati has welcomed the community to an annual “Open House” dinner, and since 1992, Chinati has consistently invited Marfa public school students to make and exhibit their art at the museum, which Michael Roch, Chinati’s director of education and curricula, sees as a “commitment to community.”72 Moore also acknowledged, however, that she was “clear-eyed” about the role Chinati has played in Marfa’s gentrification, and she envisioned Chinati functioning like a “platform” for the community, hosting discussions about the future of the town. While Krüger’s Casa prompts visitors to consider who calls Marfa home, it also raises the question: who can afford to call Marfa home?

As a crossable boundary installed next to Chinati’s southern fence line, Casa critiques the idea of Chinati as a world apart and facilitates ways of seeing the museum as a participant in Marfa’s transformation, an idea that has only gained resonance in the decades after the work’s creation. Judd once said, “The first step in architecture would be to do nothing whatsoever,” and this ethos of restraint remains visible in almost all Chinati spaces, from the repurposed military buildings at Fort D. A. Russell to what Judd considered the regionally appropriate adobe bricks that make up the walls around the Chamberlain building (fig. 21).73 Judd’s actions, however, have also had a ripple effect through the Marfa community. Since Judd began salvaging adobes in the 1970s, the material has undergone a sizable resurgence in popularity, particularly among the wealthiest members of the Marfa community. Beck Andrew Salgado, whose grandfather was born and raised in Marfa and bought an adobe house there many years ago (primarily due to its affordability), writes that “he has since seen a 500 percent increase in his taxes.”74 What began in Marfa as a building tradition by Mexican immigrants, for whom adobe was “easy [to build with] and cheap to source,” and what was initially seen by Anglos as “primitive” and undesirable, has come to represent a regional authenticity that distinguishes Marfa from New York or Los Angeles. As Marfa-based architect Stephen “Chick” Rabourn argues, around the turn of the twenty-first century, “when the fashion for Minimalism became a signifier of taste among urban dwellers with second or third homes,” Marfa adobes were purchased and upgraded into “pricey pieds-a-terre,” for which subsequent generations of home buyers paid prices “well above those sustained by the local market.”75 In 2017, the Presidio County Appraisal District created a new classification for adobe structures to reflect their “true market value,” resulting in a property tax hike of as much as 60 percent on some houses.76 The tax increase forced longtime homeowners like Salgado’s grandfather to either pay the higher taxes or sell to someone who could. Adobe was not an upwardly mobile material when Judd used it, and he believed he was salvaging a “forgotten” tradition, but, as was characteristic for his art practice, he saw value in what had been overlooked within dominant cultural practices.77 The “adobe paradox,” as Salgado calls it, is that without Judd, and without the influx of art tourism, Marfa would likely have been just another “dot on the map.”78 Now, according to Salgado and Rabourn, this same influx is causing the eradication of Mexican culture from the area.

What makes Krüger’s Casa important to think about today is that it represents the borderlands of West Texas as a hybrid place where different groups of people have formed contingent relationships. Casa also represents the border as a contested place where boundaries are porous and where the social categories that distinguish one group of inhabitants from another can appear singular yet intricately connected. In other words, Casa, which encompasses the entire landscape of the Big Bend and not just the portion that is part of Chinati, reminds us that Chinati does not constitute a world apart but is also an agent of change, entangled in the complex social and historical processes of Marfa. Judd’s actions and permanent installations in Marfa have had a profound impact on life in the area. By considering the Chinati Foundation as a verb that facilitates transformation, the museum’s stewards can critically assess how they will approach the social responsibility of their work going forward, which will likely require continuous reassessment as both Chinati and Marfa evolve.79

Today, Chinati seems to value artists-in-residence who offer counterpoints to the permanent collection.80 In 1994, Krüger was already doing just that. By erecting a wall that deconstructed Chinati’s boundaries and opened its site to the stories, people, and borderlands of the Big Bend region, Krüger built on and exceeded Judd’s vision. Casa makes visible the history of those who have inhabited this landscape as well as the contested and constructed nature of borders; in so doing, Casa provides visitors with an embodied perspective of Chinati as an intersectional place, the experience of which exceeds the foundation’s fenced perimeter. Judd’s concrete works, despite their ostensible “neutrality,” also offer a framework for viewing the landscape at Chinati as a marked and constructed site, casting the visitor’s relation to Marfa as a communal and political one. A visitor to Chinati cannot help but notice the border-patrol station next door, Highway 67 on the other side of the fence, and the military buildings that recall a history of soldiers, artists, migrants, and museum workers. At Chinati, the viewer of art is also a viewer of Marfa, standing at a crossroads.

Cite this article: Max Tolleson, “More Than a Museum: The Chinati Foundation, Home of the Brave,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.14506.

Notes

I wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers of this article for their responses to an earlier draft and Jennifer A. González for her response to this essay in its earliest manifestation, when it was presented at the Getty Research Institute’s Graduate Symposium in February 2021.

- Dimensions of Casa de los Valientes are taken from a measured drawing by Anders Krüger, originally in centimeters, which have been converted into feet. The drawing is located in the Chinati Foundation Archives, Marfa, TX. ↵

- The Chinati Foundation’s newsletter and catalogue identifies Krüger as visiting from Denmark; however, the artist is originally from Sweden. Krüger to the author, January 5, 2021. ↵

- Rob Weiner, interview with author, September 14, 2020. This essay is greatly indebted to Weiner for his insights and knowledge of Chinati Foundation history. According to him, Casa has never been conserved, and there is, as of 2021, no conservation plan for the artwork. ↵

- Walter Mignolo, “Border Thinking and the Colonial Difference,” in Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 70. ↵

- Mignolo, “Border Thinking and the Colonial Difference,” 26. ↵

- Mignolo, “Border Thinking and the Colonial Difference,” 22. ↵

- See Lonn Taylor, introduction to Marfa for the Perplexed (Marfa, TX: Marfa Book Company, 2018), 20. See also “Big Bend’s First Inhabitants,” National Park Service, accessed October 13, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/bibe/learn/historyculture/archeology.htm. ↵

- Donald Judd, “Statement for The Chinati Foundation / La Fundación Chinati” (1987), in The Chinati Foundation / La Fundación Chinati (Marfa, TX: The Chinati Foundation / La Fundación Chinati, 1987); reproduced in Donald Judd, Writings (New York: David Zwirner and Judd Foundation, 2016), 485. ↵

- Judd, “Statement for The Chinati Foundation,” 487. ↵

- In 1968, Judd began developing his idea of the permanent installation at 101 Spring Street, a building and residence he acquired in the Cast Iron District of New York, which was then elaborated in Marfa, Texas, at his home he called “The Block.” Chinati was an extension of this idea on a greater scale. ↵

- Donald Judd, “Judd Foundation” (1977), in Judd, Writings, 285. See also Judd, “Statement for The Chinati Foundation,” 487. ↵

- Judd, “Statement for The Chinati Foundation,” 487. ↵

- By the time Judd published his statement for Chinati, he had already dedicated about eight years to rehabilitating the defunct military base, Fort D. A. Russell, and he had completed by two-thirds his original goal of installing work by John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin, and himself at the site. Between the time Chinati became independent from the Dia Art Foundation in 1986 and Judd’s death in 1994, the permanent collection grew from three completed installations (two by Judd and one building dedicated to the work of Chamberlain) to nine installations, including works by Roni Horn, Ingólfur Arnarsson, Ilya Kabakov, Richard Long, Claes Oldenberg and Coosje van Bruggen, and David Rabinowitch. During this most intense period of the collection’s growth, most of the added works were made for the site by artists whom Judd invited to visit and create in dialogue with Marfa, although the works by Long and Rabinowitch were acquired and installed by Judd. Following Judd’s death, works by Carl Andre, John Wesley, Dan Flavin, and Robert Irwin were permanently installed based on Judd’s previously stated desire to include these artists in the collection. ↵

- Judd, “Statement for The Chinati Foundation,” 486. ↵

- Taylor estimates that Judd created between thirty and fifty permanent jobs in Marfa (introduction to Marfa for the Perplexed, 24). ↵

- Taylor, introduction to Marfa for the Perplexed, 30. ↵

- Sterry Butcher, “Scenes of a Town: The Why of Marfa,” in Taylor, Marfa for the Perplexed, 12. ↵

- Marianne Stockebrand, ed., “The Journey to Marfa and the Pathway to Chinati,” in Chinati: The Vision of Donald Judd (Marfa, TX, and New Haven, CT: The Chinati Foundation / La Fundación Chinati and Yale University Press, 2010), 46. ↵

- See James Meyer, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001); Jennifer Roberts, Mirror-Travels: Robert Smithson and History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Robert Morris’s Art Strike,” in October File: Robert Morris (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013); Dawna L. Schuld, Minimal Conditions: Light, Space and Subjectivity (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018); Cristina Albu and Dawna Schuld, eds., Perception and Agency in Shared Spaces of Contemporary Art (New York: Routledge, 2018); Edward A. Vazquez, Aspects: Fred Sandback’s Sculpture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017). ↵

- In his lifetime, Judd expressed an interest in transforming the former Fort D. A. Russell mess hall on Chinati’s campus into a space dedicated to the history of Fort D. A Russell. Judd placed protective frames over the murals in that space designed by soldiers, but this was the only intervention Judd made to the mess hall before he died. The former mess hall is accessible to tourists and remains in the state Judd left it when he died. ↵

- Krüger to the author, January 5, 2021. ↵

- Chinati’s former director Jenny Moore said she began residing at Chinati after she was hired in 2013 (Moore to the author, September 23, 2021). Marianne Stockebrand said she lived at Chinati while she was director (conversation with the author, November 18, 2021). ↵

- The few people who know of the work refer to it as “The Wall.” ↵

- Stockebrand, “John Wesley Gallery, 2004,” in Chinati, 252. ↵

- Visiting artists have occasionally made work in the outer zones of the Chinati campus, which are typically inaccessible to the public except under certain circumstances. However, works made by these artists, who include Rackstraw Downes, Katherine Hubbard, Erin Shirreff, and Andre Gregory, have all been dismantled, leaving no traces. ↵

- Krüger to the author, January 5, 2021. ↵

- See Krüger’s website for images of works made by the artist: http://anderskruger.se/page/2 (accessed March 6, 2021). ↵

- For more on the arc of Krüger’s artistic career, see the publication sculptural considerations (Värnamo: Vandalorum, 2012), published in conjunction with Krüger’s exhibition titled and time is just a mental tool we have invented to control and rationalize our spatial activities / och tiden är endast ett mentalt redskap vi har uppfunnit för att kontrollera och effektivisera våra rumsliga göromålat at Vandalorum, Centrum för Konst och Design, Värnamo, September 1–November 18, 2012. ↵

- Marianne Levinsen and Anders Krüger, “Terra Incognita: Trondheim’s July 22 Memorial, Project Summary,” accessed May 15, 2022, https://landscape.coac.net/en/node/2001. ↵

- Krüger to the author, January 5, 2021. ↵

- Research for this story about Pancho Villa’s raid on Ojinaga is indebted to Lonn Taylor, who first brought this history to my attention. For more on the raid, see Taylor, introduction to Marfa for the Perplexed, 17–35; for Taylor’s history of Fort D. A. Russell in particular, see Lonn Taylor, “Fort D. A. Russell, Marfa,” lecture at the Chinati Foundation, May 1, 2011, https://chinati.org/related_reading/lonn-taylor-fort-d-a-russell-marfa. ↵

- Taylor, Marfa for the Perplexed, 22. ↵

- Mignolo, “Border Thinking and the Colonial Difference,” 84–85. ↵

- Norma E. Cantú and Aída Hurtado, “Introduction to the Fourth Edition,” in Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 6. Homi K. Bhabha is another pioneering postcolonial theorist who has foregrounded the importance and potential of “third space” border zones: “It is in the emergence of the interstices—the overlap and displacement of domains of difference—that the intersubjective and collective experiences of nationness, community interest, or cultural value are negotiated,” Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 2. ↵

- Gloria Anzaldúa, “La conciencia de la mestiza / Towards a New Consciousness,” in Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 102. ↵

- See David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 98–104. ↵

- David Bacon, “Putting Solidarity on the Table,” in Children of NAFTA: Labor Wars on the U.S./Mexico Border (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 42–59. See also David Bacon, “NAFTA, The Cross-Border Disaster,” American Prospect, November 7, 2017, https://prospect.org/power/nafta-cross-border-disaster. ↵

- David Bacon, “The Maquiladora Workers of Juárez Find Their Voice,” Nation, November 20, 2015, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/the-maquiladora-workers-of-juarez-find-their-voice. ↵

- Gloria Anzaldúa, “The Homeland, Aztlán / El otro México,” in Borderlands / La Frontera, 32. ↵

- Krüger to the author, January 5, 2021. ↵

- Krüger to the author, January 5, 2021. Thanks to the assistance of Chinati archivist Hannah Marshall, Chuck Barker’s last name was able to be located in the Chinati archives. Eliseo Martinez helped confirm the last name of Jesús “Chuy” Licon. While multiple attempts were made to locate the full name of José, it could not be identified at the time of publication. ↵

- Sterry Butcher, “Chinati Weekend: Continuum,” Chinati Foundation Newsletter 26 (2021): 8. ↵

- Judd worked with the metric system when designing the untitled works in concrete. “The late 1970s/ early 1980s was a transitional phase for Judd in this regard; although he was using both {the metric and American} system{s} of measurement at this time, he was veering toward the metric system, which is broadly speaking a simpler system that makes it easier to calculate relationships.” Stockebrand, “Donald Judd: Freestanding Works in Concrete, 1980–1984,” in Chinati, 53. ↵

- Judd, “Statement” (1968), in Donald Judd: Writings (New York and Marfa: David Zwirner and Judd Foundation, 2016), 196. ↵

- Judd, “Jackson Pollock” (1967), in Donald Judd: Writings (New York and Marfa: David Zwirner and Judd Foundation, 2016), 192–93. ↵

- For more on Judd’s anarchism, see David Raskin, “Citizen Judd,” in Donald Judd (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010). ↵

- W. J. T. Mitchell, introduction to Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 1. ↵

- After Fort D. A. Russell was closed on October 23, 1946, it transferred from the Army Air Corps to the Corps of Engineers for disposal. It then traded hands several times among private citizens before becoming the property of the Dia Art Foundation. On July 23, 1979, the Dia Art Foundation made its first purchase of the barracks and artillery sheds from Roy Godbold. “Three of the barracks units were previously restored by Godbold and contain a number of modern apartments. . . . In April 1980 the Dia Art Foundation purchased the remaining reservation property from A. E. Eppenauer, which included the Arena, formerly the Gymnasium, and surrounding acreage, as well as the field that fronts the gunsheds and barracks. The last purchase included 279.15 acres from Survey 161, 241, and 244, Block 8, G. H. & S. A. Railroad Company, Presidio County, Texas.” Cecilia Thompson, History of Marfa and Presidio County, Texas, 1535–1946, vol. 2, 1901–1946 (Waco, TX: Nortex, 1985), 545–46. ↵

- Ray Zubiate, conversation with the author, September 24, 2020. Zubiate has a long and storied career in Marfa as the owner of Ray’s Bar from 1997 to 2009, where many locals, Chinati artists-in-residence, and out-of-towners mingled and listened to live music. ↵

- Dia Activity Reports, 1980–84, Chinati Foundation Archives. ↵

- I use the word “interpellate” here deliberately. Louis Althusser developed the idea of interpellation as the process whereby individuals become subjects of the state through indoctrination by ideological state apparatuses, like schools, places of worship, or cultural institutions, or by recognition from a repressive state apparatus, like the police; see Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (London: New Left Review, 1971), 123–73. Brian O’Doherty directed an ideological critique at the white cube gallery space and was one of the first to thoroughly examine its techniques for interpellating individuals within aesthetic frameworks of experience; see Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (Santa Monica, CA: Lapis, 1976). While the Chinati Foundation does not reflect the ideology of the white cube, it nevertheless interpellates individuals within its own ideological program, which this essay begins to articulate. ↵

- See Ann Temkin, “Introduction: The Originality of Donald Judd,” in Judd (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2020), 12. For more on the impact of Judd’s historicization as a sculptor, see Max Tolleson, “Judd,” ASAP/Journal, July 22, 2021, https://asapjournal.com/judd-max-tolleson. ↵

- Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (1979): 30–44. ↵

- Hal Foster, “The Crux of Minimalism,” in Return of the Real (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). ↵

- Vazquez, Aspects, 35. ↵

- Albu and Schuld write that this turn marked a shift toward a “less self-important” object and a range of hybrid practices that included environments, happenings, installations, systems art, situational, and participatory art (“Beside Ourselves,” in Perception and Agency in Shared Spaces of Contemporary Art, 4). ↵

- After Judd published the essay “Specific Objects” in 1965, his work became closely associated with that term, even though Judd’s essay mainly described work by other artists; see Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” Arts Yearbook 8 (1965); reproduced in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975 (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975): 181-189. The critic Michael Fried tied Judd’s nascent legacy more firmly to object making in “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum 5, no. 10 (1967): 12–23. In the ensuing decades, Judd’s work has been celebrated as a breakthrough in sculptural innovation while also used as a foil against which later post-Minimalist developments have been compared. Ann Temkin, chief curator of the exhibition Judd (2020–21) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, for example, identified Judd’s sculptural innovations of the 1960s as the moment when he found his original visual language. He developed what came after, however, within an “exceptionally narrow” set of parameters; see Temkin, “Introduction,” 12. Vazquez, on the other hand, situates Judd within the canon of Minimalism as a maker of discrete objects that he associates with wholeness; this allows Vazquez to then contrast Judd with Fred Sandback who, he argues, exceeds Judd’s objecthood by engaging the greater totality of architectural space (Vazquez, Aspects, 4). While harboring different objectives, both accounts strongly associate Judd with the “specific object” and the work he was making in the 1960s. ↵

- Rosalind Krauss, Denis Hollier, Annette Michelson, Hal Foster, Silvia Kolbowski, Martha Buskirk, and Benjamin Buchloh, “The Reception of the Sixties,” October, 69 (Summer 1994): 3–21. ↵

- Jennifer L. Roberts, Mirror-Travels: Robert Smithson and History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 6. ↵

- Cristina Albu and Dawna Schuld, “Beside Ourselves,” 4. ↵

- Dawna L. Schuld, “Being Nowhere: Desert Situations,” in Minimal Conditions: Light, Space, and Subjectivity (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 102. ↵

- Albu and Schuld, “Beside Ourselves,” 2. ↵

- Albu and Schuld, “Beside Ourselves,” 3. ↵

- Albu and Schuld, “Beside Ourselves,” 3. ↵

- Donald Judd, “Statement” (1977), in Judd, Writings, 287. ↵

- See Robert Smithson, “Cultural Confinement,” Artforum 11, no. 2 (October 1972): 32; Lucy Lippard, “Escape Attempts,” in Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973), vii–xxii; Daniel Buren, “Function of the Museum” (1970), in Theories of Contemporary Art, ed. Richard Hertz (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1985); Douglas Crimp, On the Museum’s Ruins (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993). ↵