Naming Naquayouma: A Collaborative Approach to American Murals and Indigeneity at the 1937 International Exposition

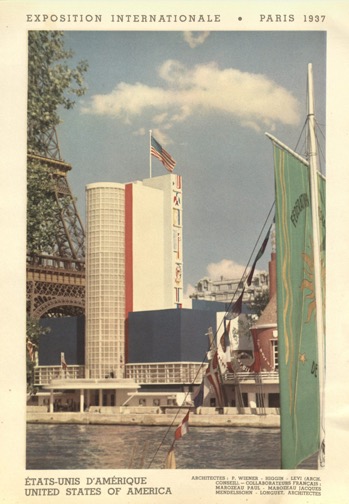

From their position on the banks of the Seine, the two ninety-foot-tall murals adorning the United States’ national pavilion towered over the 32 million visitors to the International Exposition of Arts and Technology in Modern Life in 1937 (fig. 1). In accompanying exhibition materials and press coverage, several men are lauded—or derided—for these striking designs. Among them is Eduard “Buk” Ulreich (1889–1966), a painter who executed a number of murals for the Treasury Section of Fine Arts and is often credited for his work developing the stacked symbols evocative of various Native American artistic traditions employed for the US Pavilion murals (fig. 2).1 The names of designer and architect Paul Lester Wiener (1895–1967), architect Julian Clarence Levi (1874–1971), and architect and engineer Charles Higgins also often appear in conjunction with the overall project. However, the murals’ designs are deeply indebted to the contributions of a fifth man whose name has been conspicuously erased from these records: Hopi artist, performer, and knowledge holder Ernest (Eagle Plume) Naquayouma (1906–1985).

In this Research Note, we trace the erasure of Naquayouma from art-historical scholarship, correcting the record to foreground his contributions to these murals as well as other projects.2 We also reflect on the complexities of sharing histories like this one and the ways in which we, as non-Hopi scholars, have approached this work. Names—whether of people, places, or times—hold power. In this article, we do not claim to have “discovered” Naquayouma. Instead, we offer an introduction to the many ways in which this man has been misnamed and unnamed, known and erased, over the past eighty-five years. In doing so, we subscribe to an idea of the past not as fixed, finite, and singular but as contiguous with the present. This is an approach that resonates with Hopi thought. As the longtime former director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office Leigh Kuwanwisiwma says, “The archaeologists go back in time and try and retrace it. . . . And I told them Hopi doesn’t do that. We start from here.”3 Starting from now centers the ways in which the past circuitously surfaces in the present. Thus, this account of Naquayouma’s role as a collaborator in 1937 is also an account of our own collaboration as researchers: with each other, with other scholars, and with the Hopi community, which is at its center.

To date, scholarship on the 1937 International Exposition has been overshadowed by the dramatic confrontation between the hammer-and-sickle-bearing workers atop the Soviet pavilion and the Nazi eagle stationed opposite them. When we each independently began to research the largely overlooked United States national pavilion in 2018, we had little expectation that anyone else would be thinking about this topic.4 To our surprise, we were doing so less than two miles apart, as doctoral candidates at Harvard and Boston University. Davida was investigating the murals at the exposition as a means of grounding an international history of interwar mural painting. Through an examination of the murals contributed to the 1937 International Exposition by Mexico, the United States, and France, Davida’s dissertation tracks the international diffusion and translation of the strategies of Mexican muralism. Phillippa’s interest, in contrast, lies in decorative and commercial arts as cultural brokers, and her work explores the nuances of these commodities’ creation, promotion, and consumption within transnational performances of US modernity in the early twentieth century.5 When a mutual acquaintance connected us in 2021, we found not only a common research interest but a shared commitment to combating the ongoing erasure of Indigenous presence, knowledge, and creativity in the arts.

As alluded to above, neither the US pavilion nor its external decorative program have received much attention in art-historical literature. To date, the only scholar to make the building his primary subject is journalist and art critic David Littlejohn, who, in a two-page catalogue entry written in 1987, concludes that “the United States Pavilion could be considered one of the most deplorable deceptions of the Exhibition . . . once again, America proving that they had yet to learn the critical architectural lessons of the twentieth century.”6 Indeed, the pavilion is a discordant amalgamation of International Style forms: a Corbusier-inspired grain silo adhered to boxy white towers with an incongruent mix of pure polychrome walls and decorative patterning on two sides. The glass tower achieves neither the monumentality of a skyscraper nor the intimacy of a domestic structure. It was the pendant eighty-eight-foot murals executed for the pavilion’s pylon, however, that attracted both of our attention (fig. 2). These murals featured designs loosely based on Native American symbols, painted in red, white, yellow, and blue. Accented with dimensional elements, these fourteen symbols were arranged vertically in two columns on the east and west sides of the pylon. While some of the forms are easily described—a U-shape at the top of the west column or the birds and anthropomorphic figures that appear on both sides—their layered meanings are opaque to uninitiated viewers. In a 1937 article from the New York Herald Tribune (European edition), writer Francis Smith records an attempt at ekphrasis given by French artist and self-styled expert on Native American cultures Paul Coze.7 He describes the images at the top of the eastern and western series of symbols as “a common sign of corn or fertility” and “an exploit or coup among the Prairie Indians . . . symbolizing a horse stolen from another tribe,” respectively. He names a Plains “tree-trunk decoration” and “a typical Blackfoot sky” on the eastern mural as well as “a simplification of a Navajo god” (seemingly a yéí, “holy people” figure, as art historian Sascha T. Scott notes) on the western side.8 Coze recognizes the three avian forms as “thunderbirds”—naming the two near the top of each mural as “Crow” (Apsálooke) and the one near the bottom of the eastern series as “probably from a southwest tribe.” He also sees the anthropomorphic figures as “Kachina” symbols, which he defines as “a supernatural body visiting the tribes especially to care for his crops.”9 Speaking in 1937, Coze employs what was then the conventional term in Euro-American scholarship for Katsina (plural Katsinam’).10 Although a number of Pueblo peoples recognize Katsinam, they are notably crucial to the spiritual lives of the Hopi in myriad ways that necessarily complicate any art-historical work on this subject, as we will discuss further below.

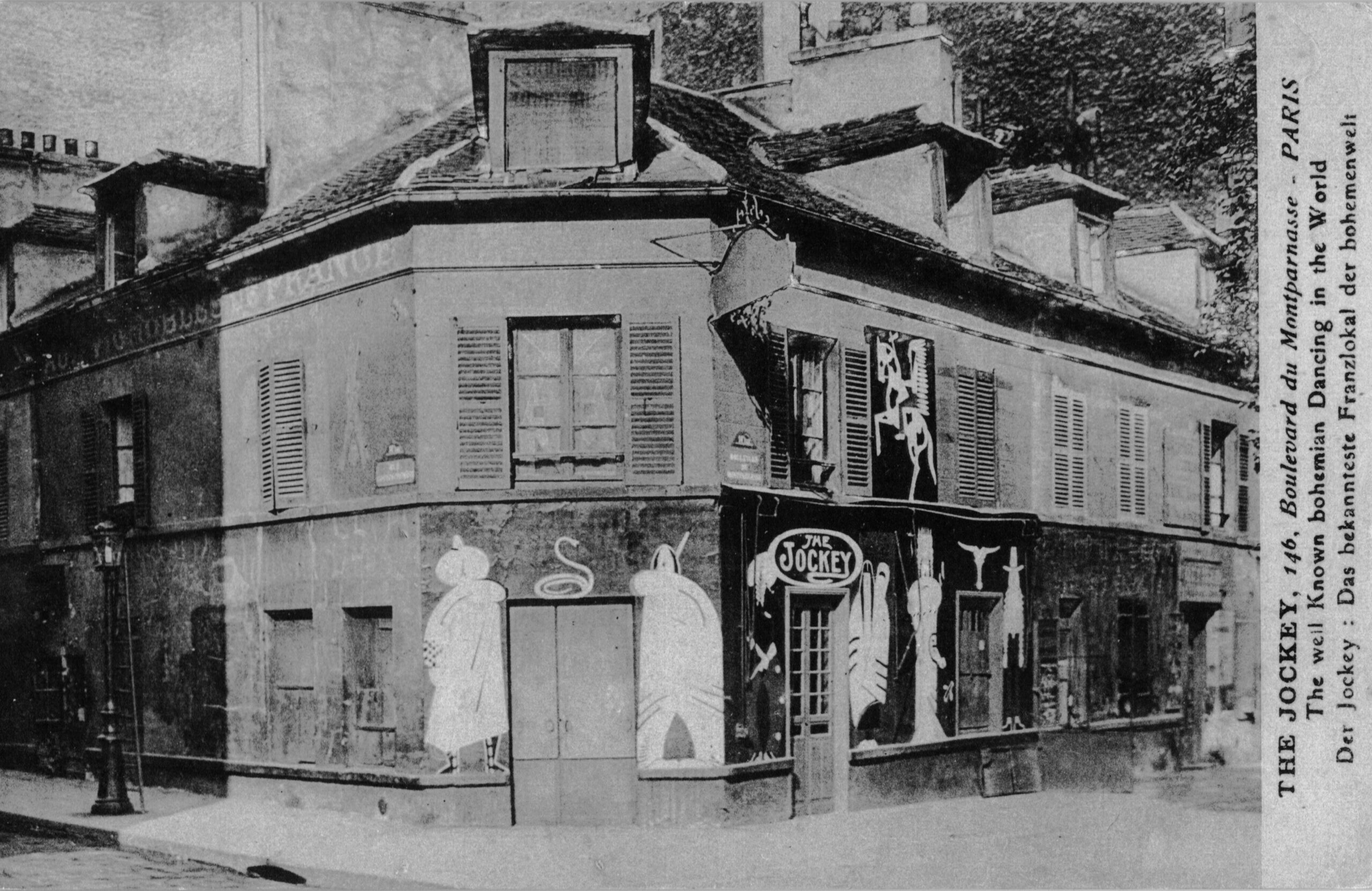

Though most members of the Parisian audience would have been unaware of these cultural complexities, references to Native American culture were prevalent across their city. The final decades of the nineteenth century had brought an influx of US citizens across the Atlantic, piquing French interest in the American West and the peoples residing there. World’s fairs, Wild West shows, and a wide range of other exhibitions and performances both fostered and fed the demand for Native American content in the French capital from the late nineteenth into the early twentieth centuries.11 Just two years before the 1937 International Exposition, Coze himself had organized an exhibition at the Trocadero Museum of Ethnography, featuring the work of students from the Studio School of the Santa Fe Indian School in New Mexico, including Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache), Mazuha Hokshina (also known as Oscar Howe, Yanktonai Dakota), and Waka Yeni Dewa (Ignacio Moquino, Zia Pueblo). To advertise this exhibition, two hundred posters featuring the students’ paintings were placed throughout the city. The posters adhere to the so-called Studio Style, with figures and patterns painted in flat planes of color, placed against a blank, customarily white background, and replete with often-amalgamated signifiers of Native American cultures. This intentionally recognizable style, also evoked by the 1937 mural, served as a prominent and profoundly flawed yardstick for measuring the authenticity or “Indianness” of contemporary Native American painting in the early twentieth century.12 Period photographs show a range of Parisian buildings adorned in this popular visual vernacular, including the facade of the Jockey Cabaret in Montparnasse (est. 1923), likely decorated by the American expatriate artist Hilaire Hiler (fig. 3).13 Although this part of Parisian history has long been told through the lens of French and Anglo-American artists, curators, patrons, and educators, these imaginaries should properly be understood as a cocreation with Native American artists, performers, and knowledge holders, who are too often left unnamed, with the individuality of their contributions undifferentiated.

Ulreich, the artist charged with the planning and execution of the murals, had a Euro-American background that made him familiar with Parisian ciphers of Indigeneity. He immigrated to the United States from Hungary with his family as a small child. In addition to studying at the Kansas City Art Institute and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Ulreich characterized his time on reservations as a young man as opportunities for “study.” During his early twenties, Ulreich worked brief stints as a “cowboy” on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (Oglala Lakota) in South Dakota and the Fort Apache Indian Reservation (White Mountain Apache) in Arizona before leaving to live and exhibit in Paris in the mid-1920s.14 Davida had learned of Ulreich’s deep interest in Native American cultures from Kimberlee Reid’s investigation into his New Deal murals.15 However, it was not until Davida was finally able to visit Ulreich’s private archives in St. Louis that she came across two newspaper clippings that set her on a path to grasping the full extent of Ulreich’s indebtedness to Native American individuals and aesthetics.

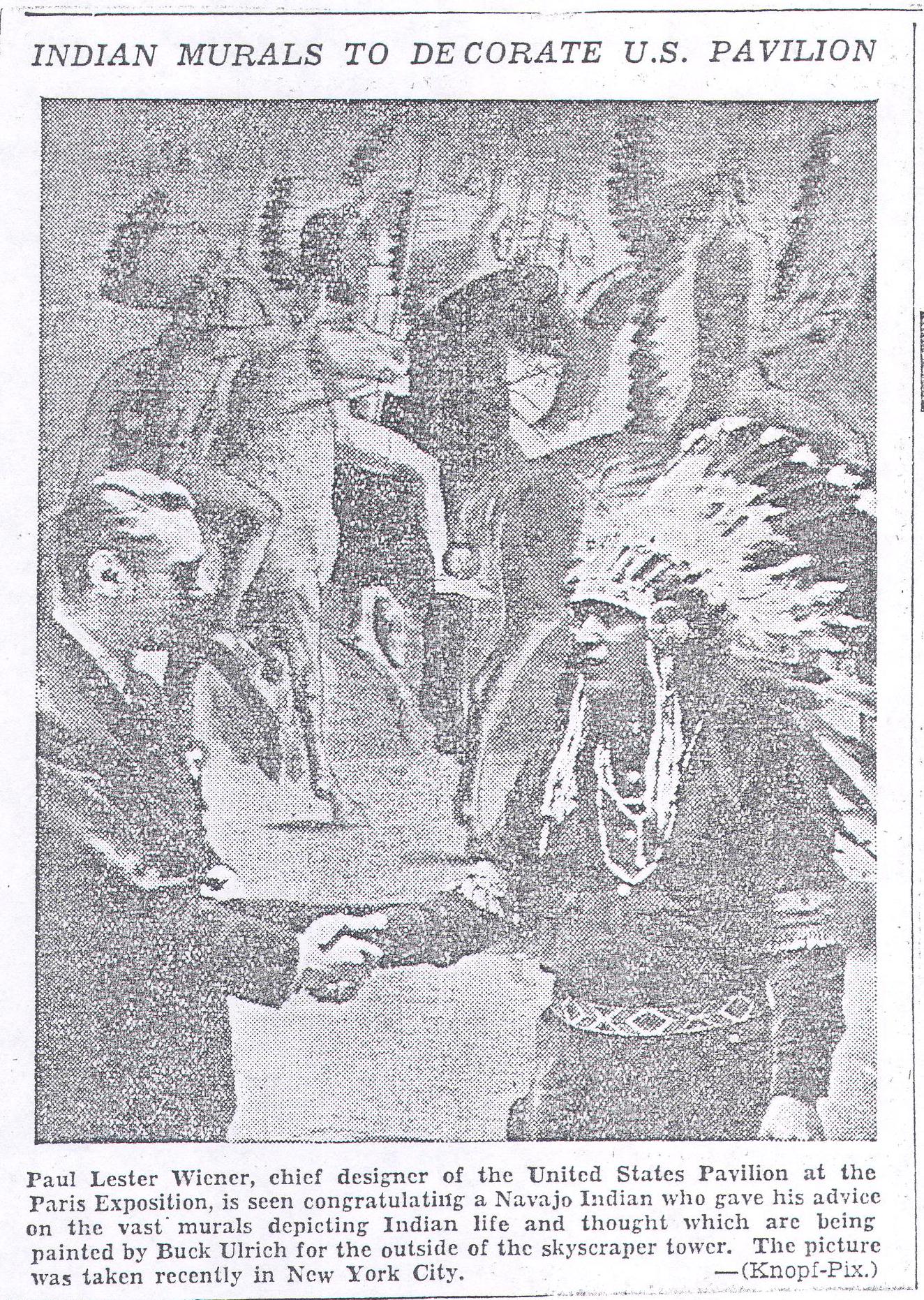

The first significant clipping that Davida uncovered was the article from the European edition of the New York Herald Tribune featuring Coze’s aforementioned description of the murals. A sentence buried in the middle of the article notes, in a painfully brief manner, that the symbols “were painted, in bright colors, by a member of the Navajo Nation.”16 The second clipping was a photograph of two men shaking hands (fig. 4). There was no publication title, date, or author—only a caption claiming that the photo showed Wiener, the architect of the 1937 pavilion, “congratulating a Navajo Indian who gave his advice on the vast murals depicting Indian life and thought which are being painted by Buck Ulrich [sic] for the outside of the skyscraper tower.”17 In the photograph, Ulreich’s New Deal mural Indians Watching Stagecoach in the Distance (1937) serves as a backdrop for their encounter.

Photographs of individuals from different cultures shaking hands carry strong associations with diplomacy. The gesture performs goodwill, partnership, and mutual respect. The caption of the photograph, however, introduces a tension. Whereas Wiener is named, the figure with whom he shares this putatively egalitarian gesture is not. The omission diminishes his importance, suggesting that his role was not significant enough for him to be named. Over time, the absence of a name compounds this devaluation. It was this incongruity, the sense that the photograph belied the lack of importance suggested by the caption, that led Davida to write a post for the Smithsonian Voices blog, published in October 2020, calling for a collaborative effort toward filling this lacuna in the record.18

Less than six months later, art historian Emily Burns was able to make a fortuitous connection.19 Having consulted with Davida on her project, Burns was familiar with Davida’s questions and research goals. When, in February 2021, Burns struck up a conversation with Phillippa about transatlantic performances of Indigeneity, she quickly realized that we were working on the same murals and that Phillippa could identify the man in the photograph: Ernest Naquayouma. The scope of Phillippa’s project, which explored the conceptual development of the building as a whole, had led her to Wiener’s archives. Working from collections at the University of Oregon, Phillippa found an archival record detailing the range of design solutions proposed by Wiener’s team to meet their creative brief: creating a building that overtly signaled both futuristic modernity and cultural heritage. To do so, they pasted together symbols of each, juxtaposing the icon of modernity, the skyscraper, with a series of Native American–inspired designs to evoke the idea of a deeply rooted national culture.

The subsequent refinement of this concept was an iterative process. In the most ambitious design, the walls of the pavilion exploded outward to become almost entirely decorative: four thin towers stretching up to the sky, united at the base with the strong contrasting horizontal of the imagined exhibition hall (fig. 5). The murals in this early incarnation are rendered simply as geometric patterns with no discernible origin or thematic meaning beyond a vague claim to Indigeneity; a stylized eagle, a spiral, jagged lines, and zigzags are arranged to tightly fill the space and layered to create alluring dimensionality. As work progressed, this fragmentary complex was pulled together into a single amalgamated structure. The distinctive glass tower was added. Surface designs of stars and maps came and went, as did a beautifully ordered geometric garden. Only the reference to Native American design survives every subsequent round of simplification and streamlining. Although the murals were the most enduring element within the design concept’s evolution, references to Naquayouma and his contributions to this particular rendering of Indigeneity are scarce. We have been unable to locate any archival evidence that might answer even the most basic questions regarding the collaboration, such as the terms of Naquayouma’s employment or when his participation in the project began and ended.

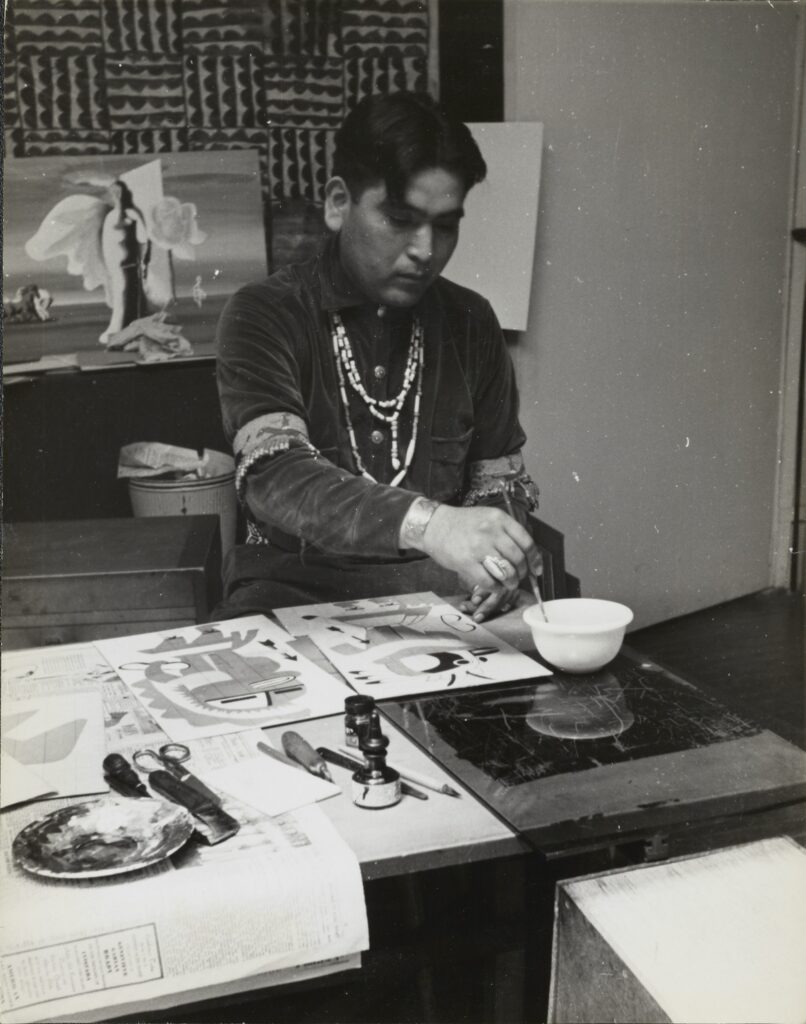

What Phillippa did uncover in Wiener’s papers was a press kit of annotated photographs, a handful of which purported to document the murals’ development from abstract concept to monumental installation. One of these images shows a man seated in front of a table laden with painting supplies and works on paper (fig. 6). His hand holds a brush above a bowl, as if caught in the moment of working. Multiple strings of beads hang around his neck; fringed cuffs wrap around his arms; and a worked silver bracelet shines on his outstretched wrist—all standing out in sharp relief against his dark collared shirt. Behind him two paintings lean casually on a textile-covered wall, and a trash can overflows with crumpled paper. Two typewritten notes are pasted onto the print’s verso. The first reads: “In order to insure having the autentic [sic] primitive atmosphere to the figures in the design, Mr. Ulrich [sic] obtained the help of Ernest Naquayouma (Eagle Plume), Hopi Indian of Toreva’Arizona.” The second caption adds further details, describing this photograph as an image of Naquayouma “mixing colors for the Exposition ornaments in the Indian way.”20

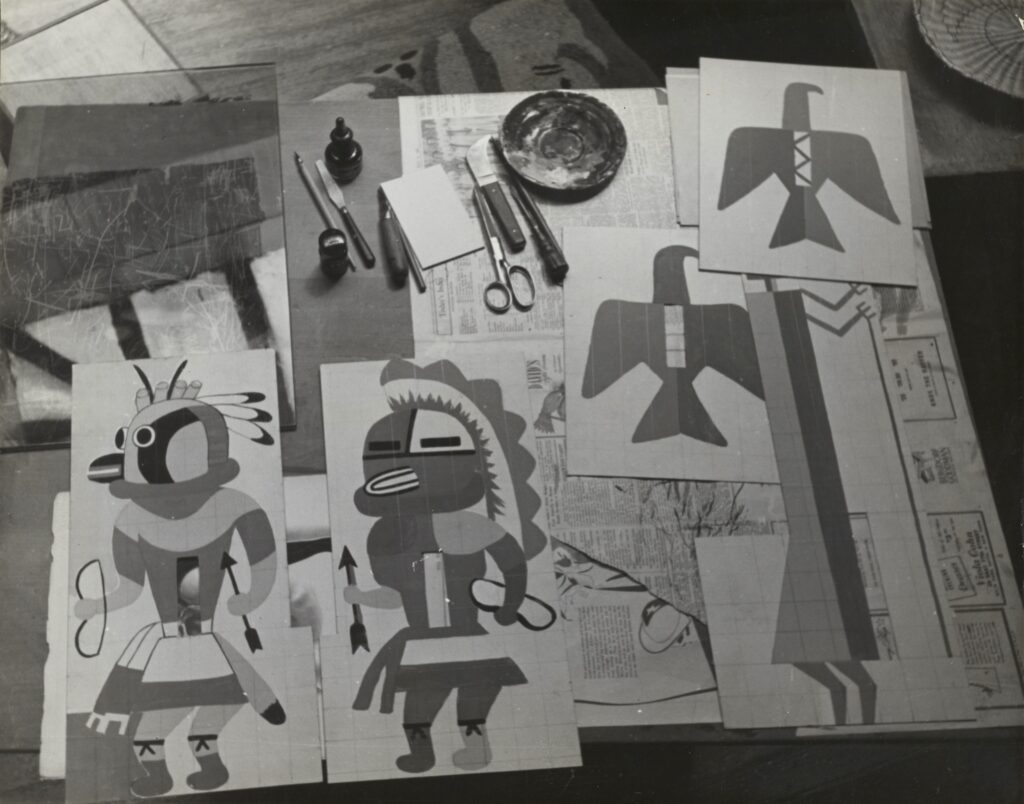

There is much to unpack in this highly staged image, particularly when it is placed in dialogue with a second photograph from the press kit (fig. 7). This print shows an array of designs on what is described on the verso as “the working table of Buk Ulreich.” Yet this photograph records the same desk at which Naquayouma posed in the previous photograph. The placement of ink, brushes, scissors, knives, and palette are identical; only the bowl and man have been removed. Moreover, although the photograph’s caption and the newsprint covering the table surface suggest an active working space, these designs have progressed past the point of loose inspiration. In the lower right, a painting of an elongated figure has been sliced along its left side, ready to be collaged into a larger composition. Rectangular shapes are cut away from an eagle and from the two Katsina figures, where three-dimensional blocks would be added in the final mural designs. Looking closely, one can even discern the faint grid overlaying each painting, likely in preparation for scaling.

In the absence of any written documentation about the nature of the exchange between Naquayouma and Ulreich, this pair of photographs does offer a limited glimpse into their collaboration. However, it provides even more information about how their relationship entered into the archival record. In these staged photographs, Naquayouma appears less as an individual and more as the embodiment of a series of long-standing ethnographic tropes. From the clothes he wears to the description of his role (“mixing pigments in the traditional way”), the image of Naquayouma presented in these US government materials conforms to the still-persistent archetype of the Indigenous maker as an ahistorical muse who bequeaths cultural knowledge to a “worthy” Euro-American artist.21 The latter, in turn, synthesizes and refines this raw material into fine art. The role of the Indigenous muse is to endorse the persona and production of the white artist, both bestowing an aura of authenticity and validating claims to an imagined national patrimony. Facts—such as the absence of any vegetal or mineral pigments and the presence of a commercially produced India ink bottle—are rarely permitted to disrupt this clean and clear narrative. We know little to nothing of how Naquayouma participated in, responded to, or felt about the construction of this narrative around his body and his work.

A third photograph from this collection offers one last fascinating hint at the designs’ evolution and Naquayouma’s removal from the record (fig. 8). In it, we see the murals executed by what appear to be Ulreich and an unnamed painter, a third process of transference. Although the dark-haired man dons Western-style clothing, Smith’s claim in the New York Herald Tribune article that these murals “were painted, in bright colors, by a member of the Navajo tribe” also invites one to wonder about this person’s identity. Was Smith referring to Naquayouma, conflating the Hopi and Diné (Navajo) peoples, as the caption of the handshake photograph did?22 Or was, perhaps, another Native American artist involved at this stage of creation?

In any event, gone are the claims to authentic pigments, mixed according to ancient tradition. The studio is replaced with a rough industrial warehouse, the precise tools with broad brushes. At the figure’s center, the wooden board, labeled “4,” hints at the paint-by-number nature of scaled reproduction. Yet, a new and curious texture is introduced to the lower half of the face of the Katsina figure. Cross patterns now fill the space above one eye. These and other details invite speculation about the process of conversion necessary to make the designs legible at a monumental scale and at a great distance from the viewer. Together, these three photographs provoke more questions than they answer. When were these design choices made? And by whom: Naquayouma? Ulreich? Wiener? When did each become, and cease to be, involved?

Our difficulty in recovering details from Naquayouma’s life was not limited to the scope of the US Pavilion project. Like many Indigenous people of the early twentieth century, Naquayouma appears in the Anglo historical record intermittently and incompletely. Here, we were fortunate enough to find another collaborator in our research: Robert Edwards, a doctoral student at University of California, San Diego. Edwards’s interest in the importance of Naquayouma’s story to American cultural history stems from his work on cultural linguistics. Edwards’s dissertation project, a subaltern history of the idea that language structures perception (the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis), challenges the scholarly predisposition to overlook or undertheorize the involvement of “ethnographic informants.” In the case of B. L. Whorf’s theory of linguistic relativity, that informant was Naquayouma. Edwards’s work resituates Naquayouma’s contributions to Whorf’s research within the context of contemporary power dynamics and the political struggles of the Hopi people in the 1930s.23 To pursue this line of inquiry, Edwards has undertaken exhaustive archival research into Naquayouma’s biography, from establishing his birth in Arizona in 1906 to charting his connections to tribal leadership and detailing his lifelong investment in Indigenous rights. In addition to his artistic production in design, painting, and metalwork, Naquayouma performed alongside other Hopi dancers, traveling to Washington, DC, to lobby against legislative efforts to outlaw Native American cultural practices and annex Hopi lands. During the many years Naquayouma resided in New York City, he served as a consultant to leading anthropologists, linguists, and ethnomusicologists of his day, led workshops for the Boy Scouts and the Camp Fire Girls of America, and performed various municipal jobs to keep his family at or slightly above the poverty line. He was also involved not only with the 1937 Exposition project but with the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Queens, which was heavily advertised with a prominent display within the 1937 pavilion.24 Shortly thereafter, Naquayouma moved to Chicago, where he cofounded the American Indian Center and was active in the midcentury pan-Indian movement for self-determination.25

The history of Naquayouma’s political advocacy, academic ties, and economic instability—painstakingly traced and generously shared by Edwards—adds important context to the 1937 mural project. This background is particularly illuminating when placed in dialogue with Naquayouma’s early involvement with M. W. Billingsley, a controversial organizer of touring spectacles that both advocated for the legal protection of Hopi culture and presented a vaudeville version of Indigeneity. Billingsley’s performances opportunistically blended traditions from across peoples and nations into an amalgamated popular image of the American Indian, not unlike the approach taken in the 1937 mural program.26 Despite the flattening and distortive nature of these activities, Naquayouma may have found a degree of agency within them. In a productive complement to Philip Deloria’s well-known phenomenon of “playing Indian,” Laura Peers observes that Native American interpreters at historic sites report a sense of “playing themselves”—a term that Peers understands as the act of “representing themselves in the present as well as their ancestors in the past.” There is a possibility inherent in the face-to-face encounter between the Native American performer and non-Native visitor, in which contradictory myths, beliefs, histories, and scripts are forced to surface simultaneously.27 Naquayouma’s ability to insert himself into such conversations—artistic, political, cultural, and scholarly—afforded him some power to shape representations of his culture. Knowing Naquayouma’s name and pursuing the ongoing work of reconstructing his biography makes visible these subversive threads and spaces for agency even within nationalistic projects like the US Pavilion. It also gestures to the existence of countless other Indigenous artists and intellectuals whose contributions to Pan-American and international modernism remain to be illuminated.

This knowledge, however, brings with it a range of complications and responsibilities. In this process of recovery, we as scholars do not wish to reproduce the violent history of Anglo individuals—archaeologists, ethnographers, and others—extracting images and information from Indigenous communities without regard for the adverse effects such appropriations might have on those communities.28 This painful history underpins much of the treatment of Indigenous makers and subjects across our field.29 At the heart of this issue is the need to trouble our discipline’s dominant norms around the nature of art, knowledge, and access—not least of which is its penchant for discovery narratives and entitlement to knowledge. As Kuwanwisiwma writes, “There is no equivalent in the Hopi lexicon for the term art. Hopi imagery—as observed in paintings and other tangible forms of expression—always carries a symbolic meaning within the context of Hopi culture.”30

The Katsina figures, which recur in all three archival images and on the 1937 pavilion itself, are emblematic of the harm this disconnect can produce. Carved Katsina tithu are divine objects, gifts from Katsinam themselves. Both the process of their creation and the circumstances of their use are spiritually charged, complicating the politics of sharing tithu or figurative images derived from them with those outside of the Hopi community. Over the past two centuries, Katsinam have become a particular site of tension between collectors and Native American communities. Even within Hopi communities, widely disparate perspectives exist on the ethics of selling tithu. While Kuwanwisiwma notes that, according to his family background, “You only carve at appropriate times; you do not carve publicly”—others feel differently, embracing the circulation of tithu more broadly. This debate is also entwined with economic necessity: many Hopi depend on the carving of Katsina tithu for their livelihoods. As Kuwanwisiwma explains, “Even though there are no good answers, I do think that a general representation of tribal interest begins where non-Hopis exploit what is intrinsically proven to be Hopi. I think I can safely draw the line there and represent the interests of those Hopis who are making a living and making their artistic reputations.”31 This “safe line” leaves the 1937 murals in question. Are its representations of Katsinam acceptable for display? Are detailed images of them acceptable for circulation?

How much of one’s culture to represent and share with the non-Native world is a question many Pueblo artists—including Fred Kabotie (Hopi), Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal, San Ildefonso Pueblo), and Ma Pa Wei (Velino Shije Herrera, Zia Pueblo)—had to navigate around the turn of the twentieth century, as railroads brought non-Native populations to Native American lands and facilitated greater cultural extraction.32 In the case of the 1937 mural, is Naquayouma’s participation sufficient to render the images admissible? How do the multiple processes of transference and reproduction factor into this equation? Is it enough that, as two-dimensional representations, the murals are not tithu—or, even more crucially, masks, which the Hopi refer to as “friends” and which should under no circumstances be represented or transferred to non-Hopis? However they are rendered, Katsina images remain part of a highly sensitive vocabulary of religious imagery, the viewing of which may be of concern to many members of the Hopi community.33 Moreover, even in the case of images that have already been widely reproduced in the past, some members of Native American communities believe the contemporary sharing of those images to constitute an ongoing harm. If it is concluded that they should not be seen, what is the proper way to treat such images within the scholarship of international modernism?

In our consideration of these questions, we turned not only to the words of Hopi scholars like Kuwanwisiwma but to the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office (CPO) for guidance.34 The Hopi CPO’s protocols enable us, as non-Hopi researchers, to conduct our work as allies and colleagues, approaching these subjects with the mentorship of Indigenous communities, with respect for their ownership over this intellectual property, and in alignment with their reparative goals and future plans. In her book Decolonizing Methodologies, Linda Tuhiwai Smith describes the importance of “the cultural ground rules of respect, of working with communities, of sharing processes and knowledge” as a cornerstone of this praxis.35 In this context, we are working in what Hopi scholar Lomayumtewa Ishii terms the wake of a historicide, a “mass execution of Hopi intellect, agency, and epistemology,” which both has allowed a distorted, limited, Eurocentric narrative to stand in for history and has alienated Hopi people from their own past. Nevertheless, Hopi history and culture persists, not only in paper archives but in oral histories, in landscapes, in songs, in architecture, in murals, in rock art, and in itaakuku (footprints).36 This history is far from simple or linear: Hopi peoples define themselves by what T. J. Ferguson and Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh articulate as their “marvelous variation,” a complex web of experience and kinship ties produced over generations of founding, leaving, visiting, and rejoining the different mesas. As such, positionality—family ties, kinship networks, participation in ritual culture—holds substantial weight in the Hopi context. Knowledge is power, and it is entrusted to those who have been trained to handle it responsibly.37 Who Naquayouma was, how he was trained, and with what intent he approached this mural project are all of vital import. For this reason, we are deeply grateful to the Hopi CPO for entering into an ongoing dialogue with us so that we may listen, learn, and avoid perpetuating or reinscribing the unethical practices of generations of scholars before us. It is with their approval that we share these images today and with the benefit of their mentorship that we can better understand Naquayouma’s life and work.

Yet the pavilion murals present ethical and interpretive questions that neither art historians nor Hopi officers can answer. The symbols that comprise these designs originate in a number of different traditions, including a Diné yéí figure, Apsálooke thunderbirds, and a Niitsitapi sky symbol. Whereas Naquayouma may have been able to decide whether a subset of the symbols included in this mural series should be viewed by non-Hopi audiences, he did not have the same authority over imagery derived from other tribes’ cultural property and heritage.38 What, then, is the proper way to treat these appropriated images? How do we explore and ethically work within the cultural indeterminacy that pervades this project? Should other CPOs be consulted? Does this question hinge on the sensitivity of the images themselves? Some culturally specific imagery is intended for public consumption, although it may hold private meanings accessible only to the initiated.

Scholarship, like art, is often a more collaborative process than meets the eye. Just as art objects may be the work of many hands, minds, and visions, books and articles that ultimately bear only one name reflect the contributions of myriad editors, reviewers, classmates, students, and friends. We are grateful for the opportunity afforded by this project to collaborate—with each other, with Edwards, with Naquayouma’s family, and with Native American cultural officers—in such a transparent and generative way. This article is only the beginning of our efforts to reconstruct the constellation of individuals whose circumstances and motivations culminated in the production of the 1937 murals. We continue to wrestle with unresolved questions and to reevaluate our own approaches and methodologies. The 1937 exposition is also only one of countless occasions in which Indigenous participants have been under-recognized for their creativity and expertise. Addressing these historical injustices requires that scholars acknowledge their own need to work with others—to share the incomplete records we encounter in archives, to openly discuss ethical quandaries posed by our projects, to welcome involvement from Indigenous communities. In doing so, we may find a way to productively make strange the culture and customs of our discipline, questioning the dominant drive to pursue, reveal, and claim knowledge and moving instead to a model of collaboration, stewardship, and cocreation.

Cite this article: Davida Fernández-Barkan and Phillippa Pitts, “Naming Naquayouma: A Collaborative Approach to American Murals and Indigeneity at the 1937 International Exposition,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022),https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13138.

PDF: Fernández-Barkan and Pitts, Naming Naquayouma

Notes

We would like to thank Emily Burns for connecting us and helping this article to take form. We would also like to thank Colleen Lucero and the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, the Naquayouma family, the Burkhardt family, and Robert Edwards for their time and generosity. We are grateful, as always, to our advisors, colleagues, families, and other collaborators. This article was made possible with support from the Smithsonian Institution Fellowship Program/Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts/National Gallery of Art.

- We make every effort in this article to refer to nations, tribes, and peoples by their own names, using the terms “Indigenous,” “Native American,” and “Indigeneity” when referencing broader categories. Although these aggregate terms are imperfect compromises and can undoubtedly reinscribe colonial frameworks, they are sometimes necessary to discuss both historical and current events. For the purposes of this article, we use the term “Indigenous” when speaking on a global scale, whereas “Native American” is employed as the more specific term, referencing Indigenous people from the lands now occupied by the United States. We use “Indigeneity” to refer to the ideas, concepts, and imaginaries of being Indigenous. On these terms and the importance of an Indigenous style, see Gregory Younging (Cree), The Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing by and about Indigenous Peoples (Edmonton: Brush Education, 2018); Devon Abbott Mihesuah (Choctaw), So You Want to Write about American Indians? (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005); and Stephanie Nohelani Teves, Michelle H. Raheja, and Andrea Smith, eds., “Indigeneity,” in Native Studies Keywords, Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2015), 109–18. ↵

- Naquayouma’s contributions to the 1937 Exposition were not only absent from the art-historical record but appear to have been missing from Hopi records as well. He is not known and celebrated in the Hopi community for this work. Even Naquayouma’s descendants were unaware of his participation in this project. ↵

- Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, 2018, cited in Hannah McElgunn, “Intertextual Politics: Presence, Erasure and the Hopi Language,” American Ethnologist 48, no. 4 (2021): 434. ↵

- Press clippings and images related to Ulreich published with the permission of Steve Burkhardt, representing the estate of Edward “Buk” Ulreich. ↵

- Fernández-Barkan’s dissertation is provisionally titled “Mural Diplomacy: Mexico, the United States, and France at the 1937 Exposition Internationale in Paris”; Pitts’s project was unfortunately deferred due to logistical and ethical concerns raised by the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly around travel and contact with Indigenous communities. Her new dissertation project is provisionally titled “Pharmacoepic Dreams: Art in America’s Medical Democracy, 1800–1860.” ↵

- David Littlejohn, “États-Unis,” in Paris 1937: Cinquantenaire de L’Exposition internationale des arts et des techniques dans la vie moderne, ed. Bertrand Lemoine (Paris: Institut Français d’Architecture, 1987), 156–57. Translation by Pitts. ↵

- Francis Smith, “Brilliant Murals Portray Lore of U.S. Indians at Exposition,” New York Herald Tribune (European edition), July 27, 1937, folder “1937,” private archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO (hereafter Ulreich archive). ↵

- Sascha T. Scott to Fernández-Barkan, October 20, 2020. ↵

- Smith, “Brilliant Murals Portray Lore.” ↵

- These descriptions reflect Coze’s interpretation; they are not necessarily a factual account of the murals’ actual or intended iconographic meanings. ↵

- See Emily C. Burns, Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018). ↵

- See Jessica L. Horton, “Performing Paint, Claiming Space: The Santa Fe Indian School Posters on Paul Coze’s Stage in Paris, 1935,” Transatlantica 2 (2017), http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/11220. ↵

- Art historian Jonathan Dentler makes this attribution based on Hiler’s involvement with the Jockey Club and similarities between these murals and others painted by Hiler. Jonathan Dentler to Fernández-Barkan, January 27, 2022. ↵

- Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, “Story of the Indian Ornament for the American Exposition Building at Paris, France,” n.d., folder “1937”; “Eduard Ulreich Chronology,” September 2003; Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, “Eduard Buk Ulreich: A Brief History,” n.d., folder “Buk Autobiography”; all sources in Ulreich archive. ↵

- See Kimberlee Ried, “New Life for WPA Art: Kansas City Archives Brings Murals Out of Storage,” Prologue (Fall 2010): 44–49. ↵

- Smith, “Brilliant Murals Portray Lore.” ↵

- “Indian Murals to Decorate U.S. Pavilion,” n.d., folder “1937,” Ulreich archive. ↵

- Davida Fernández-Barkan, “Reversing the Erasure of Native Contributions to Muralism,” Smithsonian Voices (blog), October 9, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/smithsonian-institution-office-fellowships-and-int/2020/10/09/reversing-erasure-native-contributions-muralism. ↵

- Emily Burns is a Research Notes editor for Panorama. ↵

- Photograph with two captions, Paul Lester Wiener Collection (Bx 155; hereafter Wiener Collection), box 8, folder 6, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene. ↵

- The trope of an Anglo artist receiving pigments from a Native American has a precedent in John Galt’s 1816 biography of Benjamin West, an account that made implicit claims for West’s Americanness. See Susan Rather, “Benjamin West, John Galt, and the Biography of 1816,” Art Bulletin 86, no. 2 (June 2004): 324–25. ↵

- The Hopi and Diné nations are separate and autonomous, though the Hopi Reservation is located within the Navajo Nation. ↵

- The provisional title of Edwards’s dissertation is “The Colonial History of Linguistic Relativity: U.S. Anthropology, State Science, and Native Modernity in the American Borderlands.” Naquayouma also features prominently in Edwards’s master’s thesis, “The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: Reflections of Modernity in the Borderlands of the United States” (University of California, San Diego, 2017). Although insufficiently credited, recordings of Naquayouma’s voice performing Hopi songs can be found in the Library of Congress, within the Helen Heffron Roberts Collection of Hopi Pueblo cylinder recordings (AFC 1979/104), Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ↵

- See R. John Medley and Catherine H. Ellis, “Enterprising Hopi: M. W. Billingsley, Shriners, and Second Mesa Hopi,” Journal of Arizona History 59, no. 4 (2018): 367–70, as well as press photographs of the interior of the U.S. Pavilion, Wiener Collection, box 8, folder 6. ↵

- For examples, see “Camps to Stress the Spirit of Pioneers,” New York Times, June 30, 1936, 8; and “Plan Explorer Program for Novice Scouts,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 13, 1958, NW9. ↵

- For more on Billingsley and Naquayouma, see Medley and Ellis, “Enterprising Hopi,” 339–76; and Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). ↵

- Laura L. Peers, Playing Ourselves: Interpreting Native Histories at Historic Reconstructions, American Association for State and Local History Book Series (Lanham: AltaMira Press, 2007), xxiii. ↵

- See Sascha T. Scott, “Ana-Ethnographic Representation: Early Modern Pueblo Painters, Scientific Colonialism, and Tactics of Refusal,” Arts 9, no. 6 (January 11, 2020): 1–24, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010006. ↵

- See Annika Johnson, “George Catlin, Artistic Prospecting, and Dakhóta Agency in the Archive,” Archives of American Art Journal 59, no. 1 (Spring 2020): 4–23. ↵

- The current director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office is Stewart Koyiyumptewa. ↵

- See Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, “Introduction: From the Sacred to the Cash Register—Problems Encountered in Protecting the Hopi Cultural Patrimony,” in Katsina: Commodified and Appropriated Images of Hopi Supernaturals, ed. Zena Pearlstone and Barbara A. Babcock (Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2001), 16–19. ↵

- Jessica L. Horton, “A Cloudburst in Venice: Fred Kabotie and the U.S. Pavilion of 1932,” American Art 29, no. 1 (2015): 65, https://doi.org/10.1086/681655. ↵

- Zena Pearlstone, “The Contemporary Katsina,” in Pearlstone and Babcock, Katsina, 45. ↵

- Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, “Protocol for Research, Publication and Recordings: Motion, Visual, Sound, Multimedia and Other Mechanical Devices,” accessed November 8, 2021, https://www8.nau.edu/hcpo-p/ResProto.pdf. ↵

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd edition (London: Zed Books, 2012), 310. ↵

- Lomayumtewa Curtis Ishii, “Voices from Our Ancestors: Hopi Resistance to Scientific Historicide,” (PhD diss., North Arizona University Flagstaff, 2001), 3, see also 2–22. ↵

- See Thomas Sheridan, “Oral Traditions and the Tyranny of the Documentary Record,” in Footprints of Hopi History: Hopihiniwtiput Kukveni’at, ed. Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, T. J. Ferguson, and Chip Colwell (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018), 198–213, particularly 203–6. See also T. J. Ferguson and Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, History Is in the Land: Multivocal Tribal Traditions in Arizona’s San Pedro Valley (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006). ↵

- Art historian Sascha T. Scott raised this point in an email to Fernández-Barkan, October 12, 2020. ↵

About the Author(s): Davida Fernández-Barkan is a PhD candidate in the Department of History of Art & Architecture at Harvard University. Phillippa Pitts is a PhD candidate in the Department of History of Art & Architecture at Boston University.