Nature Defamiliarized: Picturing New Relationships between Humans and Nonhuman Nature in Northern Landscapes from the American Civil War

In 1866, Winslow Homer exhibited Prisoners from the Front (fig. 1) at the National Academy of Design annual exhibition in New York.1 The painting depicts a charged confrontation between Francis Channing Barlow, a Union general, and three captured Confederate soldiers under escort. They stand before a wasteland of tree stumps and broken branches. Nicolai Cikovsky was an early proponent of the idea that this barren landscape might “carry an aspect of the painting’s profoundest meaning,” but it is only recently that scholars have begun to explore its full significance.2 Building on that line of inquiry, I argue here that the landscape in Prisoners from the Front and other Northern images from the era of the American Civil War subverted established pictorial conventions to produce new and disturbing representations of the relationship between humans and nonhuman nature.3

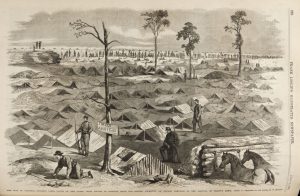

Many artists creating landscapes during the war also emphasized humans’ mastery over nature, now in a military context. For example, Edward F. Mullen’s illustration of a landscape picturing a Union encampment near the James River in Virginia (fig. 3) recalls Mix’s pioneer series, but it implies that the transformation of the landscape has occurred at an accelerated, industrial scale.6 Only four trees remain standing, echoing the soldiers in the foreground and subtly identifying the Union army as the shaping force of the environment. Tents dominate the scene, which is also thickly scattered with the stumps of the trees that supplied the army’s insatiable need for wood to make tent posts, fortifications, cooking fires, fences, roads, and railroads.7 Such a view of the Union encampment would reassure Northern viewers that the army was in full control of its surroundings.

In contrast, Prisoners from the Front turns conventional interpretations of cleared land upside down. While deforestation implies progress in the two illustrations just described, the denuded land in Homer’s painting seems to signify destruction pure and simple. As with Mullen’s scene, the composition suggests that the landscape extends beyond the frame, but only to emphasize the vast ruination of the terrain. And whereas the “Tin Pot Alley” sign leavens the scene of Union encampment with humor, Prisoners from the Front starkly depicts an endless no-man’s-land.8 The desolate setting and the tension between the figures in Homer’s painting suggest that the Northern victory is at best conditional and that it has come at great cost.9 The war has estranged Americans not only from each other, but also from nature.

The war launched a bitter struggle over who would control the land and its resources and its scope and brutality provoked a crisis of belief in the civilizing power of human society.10 As a result, landscape conventions that emphasized the human conquest of nature became incommensurate with the uncertainty unleashed by the destructiveness of the war.11 In order to register present traumas accordingly, certain Northern image makers began to adopt alternative models for depicting humans in their environments. Some war landscapes shifted the focus from human authority over nature toward humans’ intimate identification with nature by depicting both as equally vulnerable to the violence of war. Others showed an alarming estrangement between humans and their natural surroundings by picturing weather, terrain, or landscape elements as active threats to the Union army, thereby suggesting the superior power of nature. Both approaches gave a vital role to nature not present in Mix’s and Mullen’s images.12

By resituating nature on a dynamic continuum with human beings in Civil War landscapes, I offer new ways of understanding these alternative images, which could conjure up the pathos of a blasted forest strewn with human remains or the menace of a thick swamp immobilizing Union soldiers. The fluid roles that artists assigned to humans and nature in such images confirm Donna Haraway’s observation that “what counts as human and as nonhuman is not given by definition, but only by relation, by engagement in situated, worldly encounters, where boundaries take place and categories sediment.”13 During the Civil War, human insecurity—whether physical or psychological—precipitated defamiliarizing views of nature.

Although shifts in landscape imagery occurred across visual culture, illustrated weekly magazines were particularly agile in responding to the changing Northern mood. The “weeklies,” including Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, presented landscapes regularly in their coverage of the war, reaching hundreds of thousands of readers at the war’s height.14 In The Civil War and American Art, Eleanor Jones Harvey elucidates the significance of landscape imagery created by painters and photographers during the war, but does not include graphic artists. A full history of war landscapes requires attention to multiple media, since, as Harvey concedes, landscape painters offered mainly coded and “elliptical” references to the war.15 By contrast, artists working for the illustrated press, along with photographic entrepreneurs such as Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, were less constrained by established visual conventions and made battlefield views a staple of their war coverage.16 Consideration of graphic media also provides insights into Civil War paintings. For example, Winslow Homer’s background as an illustrator surely affected his pairing of soldiers and landscape devastation in Prisoners from the Front. This essay concentrates on the illustrated press as a source of war landscapes, putting such representations into dialogue with selected paintings, photographs, and prints. Attention to these popular landscapes provides significant evidence of a powerful wartime counter-discourse that challenged traditional assumptions of human dominance over nature.

Fellow Casualties of War

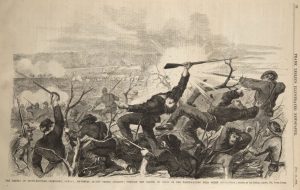

Landscapes that equated human casualties with destruction to the land were one manifestation of changed wartime attitudes. Henry Lovie’s 1862 Frank Leslie’s illustration depicting a battle in Munfordsville, Kentucky (fig. 4), is representative of this idea.17 In contrast to many battle images in the weeklies, the action presses up against the foreground rather than unfolding in the middle distance. So closely entwined are the trees and the bodies of the Confederate soldiers that they seem almost inseparable. The Southern forces are moving through abatis (defensive works created by felled trees), which mark the outer reaches of the Union lines. The accompanying article described the Confederate offensive in the following terms:

The newly formed rebel right marched from the woods in splendid order, with ranks apparently full, and the morning sun gilding their bright bayonets . . . When they appeared over the brow of the hill it was at a double quick, and not in the best of order. But all pushed on with desperate courage to meet resistance not the less temperate. With grape from the artillery, and a shower of balls from the musketry, they were met and mowed down; but they never faltered; and it was only when they sprang on the breastworks and were met with the bayonet that they fell back, leaving the field strewn with their dead and dying.18

Unlike images that show defensive works in matter-of-fact terms, Lovie’s illustration visually equates the men and branches as a means of dramatizing the disastrous assault.19 The soldier at left with his raised sword mirrors the branch to his immediate right. Even more strikingly, a tree branch at right center precisely corresponds to the angles created by the splayed arms of the two men blown back by an exploding shell. These analogies convey a dynamic sense of wide-scale destruction in which the artist draws no explicit distinction between human and nonhuman casualties. Trees and men have both been “harvested” for the war effort and are helpless in the face of the industrial war machine.

Images such as Lovie’s are deeply rooted in the long-standing culture of anthropomorphism—the “attribution of human form or character” to the nonhuman.20 In the European and American landscape painting tradition, for example, artists used natural elements such as rocks and trees as human surrogates.21 The rise of the eminent landscape painter Thomas Cole in the 1820s and 1830s coincided with newly heightened cultural interest in the associative properties of nature. From early on, Cole made a specialty of wilderness scenes in which storm-tossed trees evoked bodies in torment.22 In Tornado, 1835 (fig. 5), anthropomorphism heightens the viewer’s identification with the writhing, battered trees in the foreground. As with the formal parallels between soldiers and the abatis in Lovie’s illustration, the trees in Cole’s painting echo the fear and vulnerability of the tiny man sheltering between them.

There is, however, a critical difference between the earlier and later scenes. Already well established, images that equated humans and nonhuman nature gained new force during the Civil War because of a shift in agency. In Cole’s painting, the threat is extra-human.23 In Lovie’s, the explosions are the work of men. In fact, Union troops—not nature—have caused the destruction of the Confederate troops pictured, a point that would not have been lost on the Northern readers of Leslie’s. At the same time—Confederate enemies or no—sentimental readers surely would have responded to the pathos of a scene in which both humans and their arboreal counterparts fall helplessly to the indiscriminate violence of the war.24

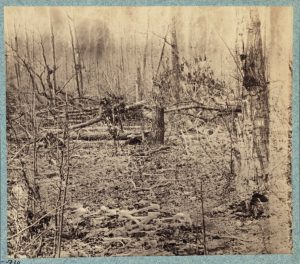

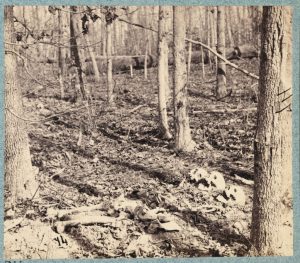

While Lovie’s illustration depicts the moment of destruction, photographs taken at the site of the Battle of the Wilderness in 1866 (figs. 6–8) emphasize the war’s long-term injury to humans as well as nature.25 The photographs, probably by William Bell, underscore the correspondence between wounded trees and bleached human bones. The damage depicted in the photographs is not fresh; the exposed bones are the remains of Confederate soldiers who were either left unburied or hastily interred in shallow graves during the Wilderness campaign two years earlier. The Union casualties of the battle had been gathered and buried in 1865.26 In some exposures, the bones are scattered randomly, and in others, they have been arranged to create partial skeletons. The location of the photographs, taken in an area north of the Orange Plank Road, connects the remains definitively with the 1864 battle.27

The photographs of the woods display an evenhandedness in their focus on both human and arboreal casualties. Their joint presence defines the Virginia landscape as one of violence and disorder. Despite attempts to restore the integrity of the bodies by arranging the bones, neither the remains nor the woods can be fully reconstructed. Together, the trees and bones serve as a terrible memento mori left behind by the battle. Rather than relying on traditional symbols of the passing of time—a candle, decaying fruit, an hourglass—to accompany the skulls, Bell connects the brutal damage to humans with damage to the land. For viewers who saw these images in the form of stereographs issued by a Baltimore photographer, the landscapes were strong reminders of woodland and human devastation scattered throughout the South.28

Such a reading reinforces earlier, firsthand accounts of the 1864 battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania. In her examination of diary entries, letters, and other contemporary sources, the historian Kathryn Shively Meier has noted that soldiers fighting in the Wilderness were particularly sensitive to their environment in 1864. Their impressions were quite unlike accounts of the battle of Chancellorsville, which occurred in the same area a year earlier.29 Meier argues that during the Wilderness campaign numerous factors, including battle fatigue, new leadership and military tactics, and the fact of fighting over an earlier battleground created a different psychology. One result was that “[m]any soldiers, especially by the time they had fought for several days at Spotsylvania, began to sympathize with nature’s wounds, often cataloguing the destruction of trees by minié balls.”30 For example, Henry Houghton, a private in the Third Vermont Infantry, wrote of a “tree twenty-two inches in diameter [that] was cut down by the constant scaling of the bullets” among his battle descriptions of the dead and wounded.31 In such accounts, the distance between damaged nature and damaged bodies has collapsed: the two appear as victims with inextricable fates.32

Herman Melville also put a spotlight on the enduring effects of the battle in his postwar poem “The Armies of the Wilderness.” Published during the same year Bell’s photographs were taken, the poem acknowledges that physical traces of war are difficult to eradicate:

But the field-mouse small and busy ant

Heap their hillocks, to hide if they may the woe:

By the bubbling spring lies the rusted canteen,

And the drum which the drummer-boy dying let go.

It continues, fusing military action and its consequences for the land:

The wagon mired and cannon dragged

Have trenched their scar; the plain

Tramped like the cindery beach of the damned—

A site for the city of Cain.

And stumps of forests for dreary leagues

Like a massacre show.

The poem also contrasts the expected cycle of the seasons with the interruption to human, plant, and animal activity caused by the war:

Where are the birds and the boys?

Who shall go chestnutting when

October returns? The nuts—

O, long ere they grow again.33

For Melville, these dramatic departures from the natural order remain palpable.

The photographs similarly capture organic and cultural disruptions that have made time difficult to gauge. The unnatural death of trees and humans, along with failure to bury the slain, extends the temporal reach of the war.34 Both poem and photographs fuse presence and absence; the visible physical traces of the war simultaneously connoting death and loss, can no longer be seen. In one of Bell’s photographs (fig. 8), for example, snapped tree trunks evoke visions of flying artillery during the heat of battle, while the dispersed canteen, boots, and skull conjure up the vanished body of a fallen soldier. Two years after the end of the war, humans and nature are still beyond repair. Conveying the carnage that occurred at the Wilderness, this fusion of violent past and melancholy present is one example of a much broader visual and literary response to the organized violence of war.

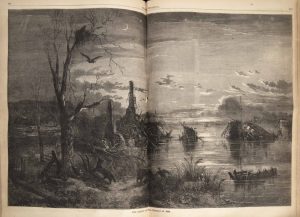

Thomas Nast’s The Result of War—Virginia in 1863 (fig. 9) dramatizes the war’s impact on the land and people by moving beyond the immediate battlefield. Published in Harper’s Weekly, the scene shows an abandoned landscape, its destruction extending not only to nature but also to what environmental historians call “second nature,” meaning the built environment.35 A collapsed bridge and the ruins of a mill, with stilled water wheel and cold chimneys, dominate the horizon line, while the submerged cart in the right foreground suggests the interruption of transportation as well as work. The house in the left background indicates that this was also a functioning domestic landscape in happier days.36 Rather than depict a specific location, the image allegorizes the war’s threat to the land and humans’ control of it.

The historian Morton Keller has described this image as “suffused with mid-nineteenth century Romantic sentimentality, conveying the pathos of the war to a Harper’s readership hungry for expressions of their own strong feelings.”37 One such personal expression comes from Captain Thaddeus Minshall of the Thirty-Third Ohio Volunteer Infantry. In November 1862 he wrote to a friend, “Oh! war is a terrible thing. In its tread it desolates the fair face of nature—all the works of the husbandman, and tramples out all the divine parts of human nature.” The following March, he wrote of nature’s efforts to rebound where he was located near Murfreesboro, Tennessee:

The spring here is coming on apace but is not as forward as it was last year. The buds of the trees are beginning to open; peach trees and plum trees are in bloom, and the birds are busy singing and building their nests. I can but reflect how nature and man are at war. Nature is strut{g}ling to give ev{e}ry thing a renewed appearance, but the grim monster, war{,} stalks on the same unvaried course of desolation and ruin. Terrible will be the condition of the South this season, nothing but the spontaneous effort of nature to indicate that the pursuit of agriculture is possible in the country.38

Minshall’s view of nature as a potential source of regeneration is not shared by The Result of War. In contrast, Nast’s illustration shows nature as surviving only in a radically degraded form. The vegetation along the riverbank is overgrown, and plants have started to sprout from the ruins. Birds of prey have roosted in the skeletal tree at left, and wild dogs scavenge along the river. The twilight sky with the sickle moon suggests that the sun has set on a once-productive landscape that arose from the collaboration of nature and humans.

People used the term “wilderness” during the 1860s to describe war-torn landscapes such as Nast’s. Rather than describing land untouched by humans, the word now connoted the forceful elimination of all human improvements, including agriculture.39 Many Americans believed that the cultivation of nature was a human responsibility, sanctioned through Christianity, and feared what its destruction portended. Nast’s landscape, which reached thousands of Harper’s subscribers, provided a shocking antithesis to landscapes that depicted the conquest of nature as a sign of human progress.

As with Lovie’s and Bell’s landscapes, Nast’s illustration also has a partisan edge. The historian Lisa Brady has argued that Union strategy included the dramatic creation of military-induced wilderness, which “functioned in the context of war not only as a synonym for waste and desolation but also as a weaponized imaginary” directed at the enemy.40 Extending Brady’s argument into the visual realm, many Northern readers would have applauded the deliberate decimation of Confederate territory pictured by Nast as a just punishment for Southern defections from the Union. In fact, in his preparatory drawing for the magazine, Nast included a skeleton hanging from the lowest branch of the tree in the left foreground. Images of a noose or a hanging man, such as those found on contemporary decorated envelopes, often symbolized the consequences of treason in popular imagery.41

The decentering of the primacy of humans within these images had radical implications for nineteenth-century viewers. The landscapes insist that humans are not the only war casualties. Rather than standing as neutral witnesses to war’s violence, the natural elements in all three landscapes are explicitly shown as bearing its brunt. However, not one among them exposes the human source of the destruction. Human agency has thus been suppressed in two ways: through the depiction of soldiers as helpless victims of war violence, and through the elision of those responsible for the ruin of life and landscape.

Nature as the Estranged Enemy of Humans

Nast’s scene also hints at a darker, more sinister role for nature that is more fully developed in other war images and writing. In the most extreme imagery, nature was coextensive with the Southern enemy, thus doubling the mortal threat to the Northern army. Union soldiers’ letters and diaries were filled with references to the difficulties of the Southern terrain—the region’s dense forests, muddy roads, and impenetrable swamps. As Robert Knox Sneden, a Union private in the Fortieth New York Volunteers, wrote about a snowstorm in January 1862 at Fort Lyon, Virginia, “We have had several storms since the 15th [and] about sixteen inches of snow now covers the ground, making it very uncomfortable camping out…The roads and camps [are] six and eight inches deep in red mud and slush… As a defense to the enemy, this Virginia mud is all as good as several regiments.”42 This conflation of enemy troops and enemy territory provides one instance of Donna Haraway’s point that the line between the human and nonhuman is not predetermined but established in specific relations. Depictions of threatening Southern landscapes suggest not only Union trepidation about fighting in unfamiliar terrain, but also larger fears about the limits of human ability to control.

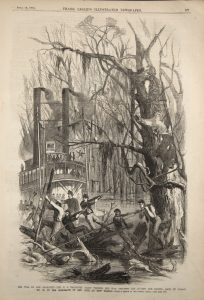

Another drawing by Henri Lovie inspired the wood engraving that appeared in Leslie’s in 1862 (fig. 10) showing the Southern landscape as an impediment to the Union Army. The illustration depicts part of the western campaign to ensure free Union movement along the lower Mississippi (the area south of Cairo, Illinois). It shows a Union steamboat, the W. B. Terry, attempting to navigate a swamp near New Madrid, Missouri. It includes a number of recognizable visual markers of the swamp: the bare, closely packed trees, hanging Spanish moss, and murky water. An article in Leslie’s described the formidable task depicted, emphasizing the distinctiveness of the terrain: “If you have never seen a Southern swamp you have no idea how thick it is; a New York elm swamp does not begin. It sometimes took 20 men a whole day to get out a half sunken tree across the bayou. Such a place as that kept us back, as none of the rafts and flats could get by, and all had to wait.”43 In his analysis of the illustration, W. Fletcher Thompson described the “heavy black smoke billowing from [the boat’s] stacks as if in agony, the crew straining to free it with windlasses and leverage poles.”44 Here, the landscape imposes stasis on humans and their means of transport rather than facilitating their movement.

The menacing landscape serves as a proxy for the South in general, and perhaps more specifically for the Confederate army. In his cultural history of the swamp in American culture, David Miller contends that “the swamp became a symbol for Southern civilization” at midcentury, “whether positively or negatively conceived.”45 He observes that swamp imagery, when used by Northerners immediately before and during the war, generally focusing on negative associations. To illustrate, Miller quotes Daniel Webster’s 1851 pronouncement that “secession and disunion are a region of gloom, and morass and swamp; no cheerful breezes fan it, no spirit of health visits it; it is all malaria.”46 In such formulations, the swamp and its surrounding atmosphere signaled decay, stagnation, and infection.

Lovie’s illustration records the ongoing difficulty of Union efforts to control the Mississippi. Due to the fact that the land surrounding entrenched Confederate positions along the river was unpredictable and difficult to navigate, the Northern army began pursuing indirect approaches rather than direct attacks. Lisa Brady points out that: “Time and time again during operations on the Mississippi, Union military leadership turned to engineering and assailed the river as an alternative to attacking their Confederate foes.”47 This included attempts to build canals and clear unused byways, as shown in Lovie’s wood engraving. However, engineering solutions had limited success due to the power of the river and complexity of the terrain.

Unlike Thomas Nast’s scene of the Virginia landscape ruined by war, the swamp depicted in the Lovie illustration exhibits an innate malevolence. Its natural obstructions block the path of the steamboat and its still water serves as a pointed contrast to the energy expended by the straining Northern soldiers. Images like the illustration of the W. B. Terry encouraged viewers to see Southern landscapes as thwarting the plans of Union soldiers, generals, and engineers, and in this way acting as an extension of the Confederate army.48

Images in which nature actively threatened humans have precedents in American visual culture, particularly in antebellum depictions of violent struggles between Native Americans and Euro-Americans. George Caleb Bingham’s Concealed Enemy, 1845 (fig. 11), for example, depicts the menacing combination of a forbidding western landscape and an Osage warrior poised for attack.49 As several scholars have noted, Bingham deliberately created formal echoes between the landscape and figure; the profiles of the rocky outcroppings and tree stump at center mirror that of the Native American.50 These visual parallels assert that nature and the crouching man are coconspirators, directing their hostility toward an invisible target below the bluffs.51

Civil War imagery presented the South as an enemy landscape, along the lines of the dangerous western frontier depicted by Bingham, but articulated its dangers in different terms. Sinister interpretations of Southern nature depended on an association in Northern rhetoric, particularly on the part of abolitionists, between the deficiencies of the regional landscape and those of Southern character. As John Greenleaf Whittier wrote in an abolitionist pamphlet in 1835, slavery had poisoned the Southern landscape so that a “moral mildew mingles with and blasts the economy of nature. It is as if the finger of the everlasting God had written upon the soil of the slaveholder the language of His displeasure.”52 As in the illustration of the Missouri swamp, Union soldiers fighting in Confederate territory faced not only an armed human enemy but also a morally infected landscape.

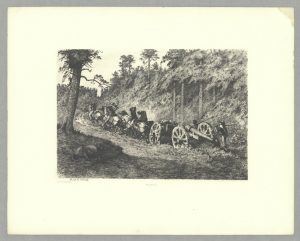

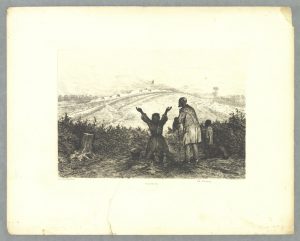

In Through the Wilderness (fig. 12) Edwin Forbes depicted an ominous landscape in the eastern theater. The etching, based on a wartime sketch Forbes made when working as a staff artist for Leslie’s, represents a disastrous Union attempt to cross the Rappahannock River and confront Lee’s forces entrenched in Fredericksburg in January 1863.53 Through the Wilderness depicts an army convoy consisting of a team of horses wearing blinders and attempting to drag supplies and a cannon along a dirt road, which a rainstorm has turned into a river of mud. The cascading mud on the hillside behind the horses and men blends with the thickness of the foliage to create an impenetrable bank. The emaciated dead horse or mule in the left foreground and the caravan just disappearing from view in the upper left suggest a chronological sequence, but the animals and men in the principal scene remain trapped in place. Forbes described the demoralizing consequences of the heavy rain during the march: “the wagon trains met with terrible difficulty, for the heavy loads were more than the animals could draw through the churned mass of mud and water. In spite of the frantic efforts of the negro drivers, a line of teams would be stalled at intervals of two or three hundred yards; mules would sink in the mire to die, and by midday everything was at a standstill; nearly one hundred thousand men with guns and transportation mired; and the long-sought-for opportunity of a battle postponed perhaps for months.”54 Although Forbes’ text goes on to relate that most of the bedraggled army was able to reverse course and return to their abandoned winter quarters, the print presents the Union forces as no match for the malevolence of nature.

A Confederate clerk stationed at Richmond reported of the failed march: “It appears from the Northern press that the enemy did make three attempts last week to cross the Rappahannock; but as they advanced toward the stream, the elements successfully opposed them. It rained, it snowed, and it froze. The gun carriages and wagons sank up to the hubs, the horses to their bodies, and the men to their knees; and so all stuck fast in the mud.”55 As if in collusion with the protracted war itself, weather and terrain combine to immobilize the human actors in Forbes’ print, to the advantage of the Southern army.

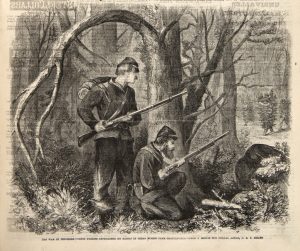

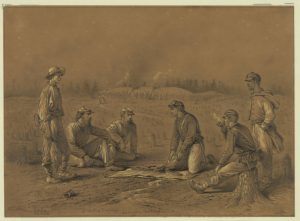

A wood engraving from Leslie’s, after a drawing by C. E. F. Hillen (fig. 13), raises the stakes by representing a direct collaboration between Southern forces and nature.56 Dating from 1863, the image presents two Union picket guards on alert in Tennessee. In the distance to the right, several Confederate soldiers disguised in cedar branches are approaching. The two watchful guards have not yet determined what they might be facing. Both peer into the distance but have made no move to confront the enemy or to alert their fellow soldiers. The article related to the illustration emphasizes the stealth (and literary roots) of their attack: “They have evidently been Shakespeare scholars and have learned a lesson from Macbeth. We have here not a whole wood marching, but single trees moving in the dusky twilight, cautiously and stealthily that their onward movement may be taken for the mere swaying of the trees in the wind.”57 The text continues by indicating that three years into the war, the soldiers have gained experience so as not to be fooled by such deception, but the image itself emphasizes uncertainty and danger. Even the tree branch above the standing soldier curves down around him as if in deliberate menace.

The motif of picket duty alone in a dangerous landscape appeared repeatedly in the illustrated press.58 Separated from comrades, such sentries represented the amplified vulnerability of soldiers in relation to their environment. They are often depicted on night duty, either alone or in a small group, overshadowed by the surrounding landscape. “The Picket-Guard,” a poem that appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1861, recounts the loneliness and anxiety of a soldier patrolling along the Potomac River:

He passes the fountain, the blasted pine-tree,

The footstep is lagging and weary;

Yet onward he goes, through the broad belt of light,

Toward the shade of the forest so dreary.

Hark! Was it the night-wind that rustled the leaves?

Was it moonlight so wondrously flashing?

It looked like a rifle—“Ha! Mary, good-by!”

And the life-blood is ebbing and plashing.59

Prefiguring the possible fate of the pickets in Tennessee shown in the illustration, the picket guard in the poem loses his life because he confused the sounds and sights of nature with the movement of the enemy. The threat is even more potent if enemy and nature conspire actively together. In a heightened level of identification, hostile nature comes to embodied life in the image—the trees are now capable of movement and come bearing arms.

Herman Melville also captured the fear of conspiratorial nature in his poem “The Scout Toward Aldie,” inspired by the deadly forest raids designed by Colonel John S. Mosby, commander of Virginia’s Partisan Rangers.60 The poem is written from the perspective of a nervous detachment of Union troops who, thinking that they are surprising the enemy, meet a woman who lures them into a Confederate trap. It begins with a description of Mosby’s feared reputation in camp:

Unarmed none cared to stir abroad

For berries beyond their forest-fence:

As glides in seas the shark,

Rides Mosby through green dark.61

The poem builds tension through the ever-changing forest setting. At points it is lovely: “The settled hush of birds in nest / Becharms and all the wood enthralls.” In others, however, it is a source of fearful confusion:

“but what’s that dangling there?”

“Where?” “From the tree—that gallows bough;

“A bit of frayed bark, is it not?”

“Ay—or a rope; did we hang last?”62

In the end, it is the duplicity of the mysterious woman and nature itself that deliver the Union soldiers into Mosby’s hands. Melville presents the forest as fully complicit: “Maple and hemlock, beech and lime, / Are Mosby’s confederates, share the crime.”63 As in the illustration of the camouflaged attack, the poem creates no distinction between trees and humans as enemies. Nature is an active agent in the war, and humans—Northern soldiers—are powerless and vulnerable in the face of its hostility.

Postwar Visions of Humans and Nature

When considering the visual legacy of the war, two compelling landscapes by Edwin Forbes and Winslow Homer (figs. 14 and 1) offer drastically different portraits of the exchanges between humans and nonhuman nature. Their creators reassign new meanings to traditional symbols, such as tree stumps, as a way to arrive at antithetical outcomes; Forbes’ landscape represents nature and humans as bound closely together and Homer’s shows them as fatally estranged. Both images are based on wartime events but were executed after its conclusion; due to this temporal collapse, they appear to predict or anticipate the consequences of the war. The landscapes represent minority views in the postbellum period, however, thus highlighting how situation-specific the radical images of defamiliarized nature were.

Edwin Forbes’ The Sanctuary, 1876 (fig. 14), from his series, Life Studies of the Great Army, melds several different visual motifs from the war in its vision of an African American family reaching Union lines and freedom.64 The figures in the shadowed foreground draw the viewer’s attention. All three face away, their gazes directed to the Union lines. They include a woman with a pail at her side, kneeling with her arms raised, an older man who has removed his hat and is resting on a walking staff, and a young boy. The domestic detail of the dog sitting next to the child suggests that the three fugitives form a family. According to the artist, the group who inspired the print escaped from the plantation where they were enslaved, and “avoiding highways to escape capture, tramped through wood and thicket, and came, weary and foot-sore, in sight of the Union lines at daybreak.” Forbes continued by narrating the event in the dramatic fashion of religious visions:

The old mother dropped to her knees and with upraised hands cried “Bress de Lord!” while the father, too much affected to speak, stood reverently with uncovered head, and the wondering, bare-legged boy, with the faithful dog, waited patiently beside them. As the bugle notes of the reveillé echoed across the fields, and the star-spangled banner waved out from the flag-staff on the breastworks in the bright morning sun, I murmured, “A Sanctuary, truly!”65

The landscape in The Sanctuary plays a role as symbolic as the figures. The scene before them shows an area denuded of trees. Familiar from other encampment scenes, countless stumps litter the field, which gives way at left to the fences and chevaux de frises [sharpened wooden spikes in an interlocking framework] just below the earthen mounds at the crest of the hill. The scene recalls the stump-strewn Union encampment illustrated in the Leslie’s print (fig. 3). If the landscape appeared on its own, or was populated by Union soldiers, it would have a fairly conventional message; however, with the presence of the family, the scene encourages a very different reading. Here the cleared landscape is not just a literal depiction of one Union line, but instead is a sanctuary in Forbes’ terms.

The clearing of the land in Forbes’ print symbolizes the elimination of an older, oppressive social order. The artist reinforces this point by including two detailed tree stumps in the foreground. The alteration of the land and the implied violence of the war have cleared a path to freedom. The fact that the clearing has been accomplished by the Union army indicates that Northern soldiers are the primary actors in this drama, but the print also hints at a possible new relationship between former slaves and the land.

Forbes’ print belongs to a larger group of Northern images that depict African Americans fleeing enslavement.66 In both military and popular usage, former slaves living and working behind Union lines were referred to as “contrabands.”67 Images presenting contrabands often showed them in motion within spaces of transition: on the road or reaching the outskirts of a Union encampment, as signaled by the presence of a picket guard or fortifications.68 The historian Amy Murrell Taylor acknowledges the limitations of the designation contraband, a legal term that described goods illicitly traded during wartime, but not people. She argues, however, that the word continues to convey something about the uncertain status of the people it described:

Those who used the term in the 1860s understood that the men and women of this era were experiencing something very distinct—a transitional period somewhere between slavery and freedom—so a distinct language was needed to describe their unusual position. To call them “freedmen” or “slaves” would have been to overlook the period of limbo during which they were not really free but not really enslaved while living near the Union army.69

By visualizing thresholds, images such as The Sanctuary graphically represent the liminal state that the term “contraband” implies. Forbes poised his family group physically and symbolically at the border between two landscapes. Unlike the war landscapes that aligned human and natural casualties, Forbes’ creates a sympathetic identification between the human and nonhuman elements through the theme of sanctuary.

An 1864 Harper’s Weekly view of the Freedman’s Village in Arlington, Virginia, (fig. 15) offers an instructive comparison to The Sanctuary in the relationships it establishes between the foreground figures and a human-dominated landscape. The Harper’s illustration, based on a drawing by Alfred R. Waud, depicts the village newly created on the confiscated estate of Robert E. Lee for people freed by the Emancipation Proclamation.70 One year old, the village that appears in the illustration is already quite substantial, including, as the magazine reported, residences as well as a school, hospital, and home for the aged.71 The topographic view resembles promotional images of new towns on the western frontier. It also displays striking similarities to Forbes’ Sanctuary. Both images open up to a panoramic expanse; both incorporate tree stumps in the foreground to indicate transformation; and both include a family in the foreground, comprised of an African American woman and two small children in Waud’s image. A man, identifiable as a soldier from his uniform and shouldered weapon, is also present in the foreground.

The view of the village serves as one of the possible futures imagined by the figures in The Sanctuary. Here, the landscape of war has transformed into one of civilian life (although the War Department administered the settlement). The promises of emancipation—housing, paid work, and community—are represented in the print or alluded to in its published description. Government action, not General Lee, put the landscape to work on behalf of the freed people. The village, however, did not represent a full transformation in the lives of its residents. The Harper’s text echoes a frequent refrain of white benevolence by remarking that the settlement was “erected especially for the use of such contrabands as, failing to provide for themselves, become a burden to the Government.”72 Both the textual description of the village and Forbes’ image depict former slaves as dependent for protection on the Union. In addition, histories of the village trace persistent tensions between residents and the War Department and Freedmen’s Bureau.73 The Harper’s illustration, however, still goes one step further than The Sanctuary in its visualization of a landscape transformed for a new purpose antithetical to its function in the recent past.

The Sanctuary conveys the prospect of freedom through the depiction of a place. Other representations of contraband figures, including some by Forbes himself, often used the prominent placement of white soldiers to reinforce the boundaries of Union-controlled territory, but the only soldiers in this scene are two tiny figures barely visible at the horizon to the left of the flag.74 In addition, Forbes gave fresh meaning to the modification of nature by human hands. While presented in familiar visual terms, the landscape in The Sanctuary is given a new witness—the African American family—and a new moral purpose—emancipation. Forbes’ decision to use the print as the culminating image in both his postwar etching series and illustrated memoir suggests that for him it articulated a significant legacy of the war. Created more than a decade after the Harper’s Weekly illustration of the Freedman’s Village, and with knowledge of the failures of Reconstruction, The Sanctuary deliberately envisions an earlier moment of possibility.

We can now return to the unrelenting desolation of Homer’s Prisoners from the Front. Like Forbes’ Sanctuary, Homer’s painting draws from existing war iconography but infuses the scene with a heightened sense of estrangement. Research has clarified that while Prisoners depicts no specific location, the landscape was inspired by the battleground of Petersburg, Virginia.75 Homer sketched in the area, responding to the way that huge numbers of trees there had been eliminated in the course of the long-term siege. The washed out sky and drab coloring of the earth reinforce the barrenness of the land. Two pine branches with their needles intact provide the only visual relief from the devastation. In war imagery, pine branches served as a symbol of the South; their presence here launches an ongoing dialogue with the human confrontation above them.76 Homer placed both branches strategically: the strong diagonal of the one behind Barlow highlights his presence and accentuates his dynamic pose; the other, sprawling horizontally, entwines one of the two presumably confiscated rifles in the foreground. The combination of rifles and branches creates a potent war emblem that weaves weaponry and the land explicitly together. Homer presents the Civil War as a war on the Southern land, not just on enemy troops. The fact that the greatest expanse of blasted land lies behind the Southerners reinforces this point.77

The palpable destruction in Homer’s painting resists interpretation as a triumphant image of Union victory. Although environmental historians have emphasized that the army that controlled the land ultimately controlled the outcome of the war, the inhospitable landscape makes the Union success in capturing these prisoners seem provisional at best. The stalemate comes into even sharper focus when comparing Homer’s painting to an 1876 drawing by Edwin Forbes, Pickets Trading Between the Lines [Traffic Between the Lines], based on an exchange Forbes witnessed during a long siege (fig. 16). The two scenes share many features, including the positioning of Union and Confederate soldiers in front of a deforested landscape. Forbes depicted two relaxed groups of soldiers exchanging coffee and tobacco during a lull in the battle. The trees have been cleared as part of the Confederate Army’s encampment; defensive abatis, earthworks, and smoke from campfires—all markers of a resident army—appear on the horizon. Forbes, like Homer, was inspired by the Petersburg landscape, but the more intimate scale and attention to details in his drawing conveys a more specific sense of place.78 In contrast, Homer depicts a tense standoff occurring in the midst of a featureless wasteland. There is no sign of an encampment and not even the dimmest prospect of permanent occupation. It is a liminal realm that questions Union dominion over Confederates, human dominion over nature, and nature’s dominion over humans.79 It also implicitly maps out the multiple challenges of the postwar era: the reintegration of the South into the Union and the healing of the physical and psychological wounds of the war. In this, the devastation of the land becomes central to the message of the painting. Interestingly, the commentary on Prisoners from the Front in the contemporary Northern press did not mention the landscape at all.80 Of course, this may indicate that the critics did not think it was important. They devoted most of their reviews to the different figural types—both Northern and Southern—that populate the painting. At least a few of the reviewers thought that a careful examination of these figures would explain why the Union had won the war, finding resolve in the figure of Barlow, and arrogance or ignorance in the Confederates.81 The focus on the figures is also in keeping with an interpretation of Prisoners from the Front as a history painting or a genre scene. A more compelling reason for the absence of commentary on the landscape, however, is its complete familiarity after four years of war. Unlike the figures, who might require “decoding” in order for the public to incorporate them within the proper ideological framework, the meaning of the devastated landscape may have been too obvious to require comment. The omission suggests that Homer’s departure from the conventions governing the representation of military conquest was more radical than his rendering of the war landscape. The press lavished attention on the nuances of the standoff between Northerners and Southerners to explain the elision of explicit heroism in the painting, but could rely on the public’s awareness that a shattered landscape conveyed symbolic meaning.

Read in conjunction, Forbes’ and Homer’s landscapes present contradictory interpretations of the war’s legacy in the realm of relations between humans and nonhuman nature. The Sanctuary imagines a new start, showing African Americans in potentially healing harmony with the land, but Prisoners from the Front paints an image of entrenched physical and psychological damage. Both landscapes manipulated established iconography to realign the relationship between humans and nature. Impossible to imagine before the war, the scenes remain incomplete, transitory, and unsettled visions. In contrast, other postbellum landscapes moved deliberately away from anxious characterizations to suggest that humans once again held sway over the land. For example, George Inness’ monumental Peace and Plenty (1865; The Metropolitan Museum of Art), imagined a return to the pastoral mode, complete with cultivated fields and a flock of sheep. Similarly, most postwar landscapes of the American West depicted wondrous views of pristine nature that celebrated, in Angela Miller’s words, “the virtues of retreat from history into nature,” thereby sidestepping the questions the war raised about the ongoing interactions between humans and the natural environment.82 There are rare postbellum images that represented the results of human depredation in stark terms, such as Sanford Gifford’s Hunter Mountain, Twilight (1865; Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago) or certain late-nineteenth-century book and magazine illustrations showing the despoliation of American forests.83 However, they are also different in kind from the war landscapes under review. While they acknowledge human culpability more directly, they do not have the same emotional pull of the wartime landscapes juxtaposing human suffering with natural destruction. Their visual emphasis is on preservation rather than on the intimate, bodily connections that bind humans to nature or cast nature as a frightening enemy.

At its heart, the visual culture of landscape explores relations between humans and nonhuman nature. Despite different media and contexts, the striking images analyzed in this essay introduced fluidity into traditional human/nonhuman boundaries by undermining the certainty of humans’ control of nature. This representational flexibility, appearing prominently in the illustrated press, gave voice to the uncertainties and powerful emotions that seized Americans during the Civil War. As these anxieties waned in the postwar era, artists returned once again to depictions of a comprehensible natural world that existed for the pleasure and benefit of human society.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the executive editors of Panorama, Ross Barrett, Sarah Burns, and Jennifer Jane Marshall, as well as the journal’s anonymous readers for their valuable suggestions. In addition, Lisa Brady, John Cummings, Katy Meier, and Eric Mink answered research questions, while Lou Masur, Vibs Petersen, Janet Wirth-Cauchon, and Mark Vitha provided careful readings of the manuscript at different stages. Thanks also to all those involved in the 2012 NEH Summer Institute on the Visual Culture of the American Civil War and to the Office of the Provost, College of Arts and Sciences, and Cowles Library at Drake University for support of my research.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1502

PDF: Lyons: Nature Defamiliarized

Notes

- For brief summaries of the salient features of Prisoners from the Front, see Marc Simpson, Winslow Homer: Paintings of the Civil War (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1988), 247–55; and Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr. and Franklin Kelly, Winslow Homer (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1995), 55–58. ↵

- Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., “Winslow Homer’s ‘Prisoners from the Front,’” Metropolitan Museum Journal 12 (1977): 171. See Eleanor Jones Harvey’s interpretation in The Civil War and American Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2012), 169–71. ↵

- My use of the phrase “nonhuman nature” refers to such things as trees, water, earth, and weather phenomena, but not animal life. ↵

- S. George Ellsworth identifies Mix as the creator of the illustrations in Turner’s history in his introduction to “The Pioneer Settler upon the Holland Purchase, and His Progress,” Western Historical Quarterly 6, no. 4 (October 1975): 426–27. ↵

- For the symbolism of the tree stump, see Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., “‘The Ravages of the Axe’: The Meaning of the Tree Stump in Nineteenth-Century American Art,” Art Bulletin 61, no. 4 (December 1979): 611–26, and Barbara Novak, “The Double-Edged Axe,” Art in America 64 (January–February 1976): 44–50. Both Cikovsky and Novak note that the multivalence of the symbol meant that it could connote progress at the same time as allowing some feelings of regret for the destruction of nature. ↵

- Mullen covered the 1864–65 siege of Petersburg for Leslie’s. For information on Mullen and the other Leslie’s Special Artists discussed here (including Lovie and Forbes), see the brief biographies in Judith Bookbinder, “In the Midst of Battle,” First Hand: Civil War Era Drawings from the Becker Collection, eds. Judith Bookbinder and Sheila Gallagher (Chestnut Hill, MA: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2009), 49–63. ↵

- See Megan Kate Nelson, Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012), chap. 3, 152, for a detailed accounting of the armies’ use of trees. She estimates, for example, that during the course of the war, campfires alone required 400,000 acres of trees per year. ↵

- See Gilbert Tauber, comp., “NYC Streets: A Guide to Former Street Names in Manhattan,” http://www.oldstreets.com/index.asp?letter=T (accessed July 28, 2012). ↵

- Harvey makes a similar point in The Civil War and American Art, 171. ↵

- For analyses of the war’s environmental impact, see Ted Steinberg, Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002); Mark Fiege, “Gettysburg and the Organic Nature of the American Civil War,” in Natural Enemy/Natural Ally: Toward an Environmental History of Warfare, eds. Richard P. Tucker and Edmund Russell (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2004), 93–109; Mark Fiege, The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012); Lisa M. Brady, War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes During the American Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012); Nelson, Ruin Nation; Lisa M. Brady, “From Battlefield to Fertile Ground: The Development of Civil War Environmental History,” Civil War History 58, no. 3 (September 2012): 305–21; and Aaron Sachs, Arcadian America: The Death and Life of an Environmental Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). For the ecocritical “turn” in art history relevant to this study, see Alan C. Braddock, “Ecocritical Art History,” American Art 23, no. 2 (Summer 2009): 24–28, and Alan C. Braddock and Christoph Irmscher, eds., A Keener Perception: Ecocritical Studies in American Art History (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009). ↵

- This crisis of landscape representation recalls the war’s threat to grand manner history painting, as described by Steven Conn and Andrew Walker in “The History in the Art: Painting the Civil War,” Terrain of Freedom: American Art and the Civil War, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 27, no. 1 (2001): 60–81. However, while the war may have sounded the death knell for history painting, as they argue persuasively, the multiple symbolic associations with nature from which artists could draw kept the landscape genre from obsolescence during the war, as did its adoption by the illustrated press (the focus of this essay) and photography. ↵

- See Linda Nash, “The Agency of Nature or the Nature of Agency,” Environmental History 10, no. 1 (January 2005): 67–69. ↵

- Donna J. Haraway, “A Game of Cat’s Cradle: Science Studies, Feminist Theory, Cultural Studies,” Configurations 2, no. 1 (1994): 64. Haraway’s investigation of the human/nonhuman ranges from her landmark essay about the fusion of the human and machine, “Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Socialist Review 80 (1985): 65–108, to her more recent study of encounters between humans and animals, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). Other significant theorists of the variety of human and nonhuman associations include Bruno Latour in science studies and Jane Bennett in political science. For an introduction to Latour’s scholarship, including his use of the concept of the “actant” (a nonhuman actor), see Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999). For Jane Bennett’s plea to take “thing power” seriously, see Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010). ↵

- On the circulation of the illustrated weeklies, see Andrea G. Pearson, “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly: Innovation and Imitation in Nineteenth-Century American Pictorial Reporting,” Journal of Popular Culture 23, no. 4 (Spring 1990): 81. See also Joshua Brown, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), and David Park, “Picturing the War: Visual Genres in Civil War News,” Communications Review 3, no. 4 (1999): 287–321. ↵

- Harvey, The Civil War and American Art, 1. As noted, Harvey’s exhibition included both landscape paintings and photographs, but they appeared in separate sections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum galleries and are treated in separate catalog essays. For other interpretations of the symbolism of Civil War era landscape painting, see Angela Miller, The Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825–1875 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), esp. chap. 3, and “Albert Bierstadt, Landscape Aesthetics, and the Meanings of the West in the Civil War Era,” Terrain of Freedom: American Art and the Civil War, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 27, no. 1 (2001): 40–59. Although my interpretation of Civil War landscapes as symbolic systems of meaning is indebted to Miller’s investigations of the landscape genre, it differs from hers in exploring the extent as well as the limits of agency given to nature in visual representations. See also Sarah Cash, Ominous Hush: The Thunderstorm Paintings of Martin Johnson Heade (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1994). ↵

- Anthony Lee points out the war’s continuation of the new genre of the photographic landscape “view” in his book with Elizabeth Young, On Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007),11. For overviews of Civil War photography, see Alan Trachtenberg, “Albums of War,” in Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), 71–118; Keith F. Davis, “‘A Terrible Distinctness’: Photography of the Civil War Era,” in Photography in Nineteenth-Century America, ed. Martha A. Sandweiss (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), 131–79; and Jeff L. Rosenheim, Photography and the American Civil War (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Lovie also made use of a wounded tree/man parallel in imagery from Shiloh; see “Retreat of Dresser’s Battery at Shiloh, April 6, 1862,” in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper supplement, May 17, 1862, reproduced in W. Fletcher Thompson, Jr., The Image of War: The Pictorial Reporting of the American Civil War (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959), following p. 160. ↵

- “Battle of Munfordsville,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 25, 1862, 78. ↵

- Examples of documentary illustrations of defensive works include “The Defenses of Washington—Fort Ellsworth, South of Alexandria,” Harper’s Weekly, January 11, 1862, 22; Edwin Forbes, “Principal Rebel Defenses at Centreville,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 12, 1862, 365, and Winslow Homer and Alfred Waud, “The Enemy’s Works near Yorktown,” center vignette from “Our Army before Yorktown,” Harper’s Weekly, May 3, 1862, 280–81. ↵

- “Anthropomorphism,” Oxford English Dictionary, second edition,1989; online version June 2012. <http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/8449> (accessed June 26, 2012). See also the series of essays on anthropomorphism that appeared in “Notes from the Field,” Art Bulletin 94, no. 1 (March 2012): 10–31, and Bryan L. Moore, Ecology and Literature: Ecocentric Personification from Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). ↵

- See Jean-Hubert Martin, Une Image Peut En Cacher Une Autre: Archimboldo, Dali, Raetz (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2009), a provocative exhibition catalog presenting double images created by European artists over many centuries, and for the antebellum United States, J. Gray Sweeney, “The Nude of Landscape Painting: Emblematic Personification in the Art of the Hudson River School,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 3, no. 4 (Autumn 1989): 42–65. ↵

- Sweeney, “The Nude of Landscape Painting,” 46–53. ↵

- Cole created contemporary religious images, including The Subsiding of the Waters of the Deluge (1829; Smithsonian American Art Museum), and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, (c. 1827–28; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), in which he presented devastated landscapes that resulted from human sin. On the continued influence of Cole’s varied landscape imagery in expressions of “millennial hopes and apocalyptic fears” during the 1850s and 1860s, see Miller, Empire of the Eye, chap. 3. ↵

- On the role of sentiment in popular representations of soldiers, see Alice Fahs, The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North & South, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), chap. 3. ↵

- Research by John F. Cummings has uncovered evidence of Bell’s trip to the area with Dr. Reed Bontecou to collect human remains for the Army Medical Museum after the war; John F. Cummings, III, “Picking up the Pieces,” Civil War Times 48, no. 2 (April 2009): 51–53. There is some mystery surrounding the photographer of the series but Cummings believes that Bell, an employee of the Army Medical Museum, took them. Bontecou is best known today for the graphic photographs of wounded soldiers taken by him, or under his supervision, at Harewood Hospital in Washington, DC. ↵

- Cummings, “Picking up the Pieces,” 53. ↵

- John F. Cummings, III, telephone conversation with the author, August 28, 2012. ↵

- Cummings, “Picking Up the Pieces,” 51. The Wilderness photographs were probably intended as internal documentation for the Army Medical Museum of the settings in which the remains were recovered and not to be made public. However, a Baltimore photographer named G. O. Brown, with his own connections to the Museum, issued some for sale as stereographs. ↵

- Kathryn Shively Meier, “Fighting in ‘Dante’s Inferno’: Changing Perceptions of Civil War Combat in the Spotsylvania Wilderness from 1863 to 1864,” in Militarized Landscapes: From Gettysburg to Salisbury Plain, eds. Chris Pearson, Peter Coates, and Tim Cole (London: Continuum, 2010), 39–56. Meier reminds her readers that the area of the Spotsylvania Wilderness was heavily forested at the time of the Civil War, although it had been cleared for agriculture and industry earlier in American history (43–44). ↵

- Meier, “Fighting in ‘Dante’s Inferno’,” 47–50, 52. Meier also contends that some soldiers saw the land as their enemy. ↵

- Ibid., 251, n. 60. The quotation appears in Henry Houghton, “The Ordeal of Civil War: A Recollection,” Vermont History 41, no. 1 (Winter 1973): 36. ↵

- See Maura Lyons, “An Embodied Landscape: Wounded Trees at Gettysburg,” American Art 26, no. 3 (Fall 2012), 44–65. ↵

- Herman Melville, “The Armies of the Wilderness,” in Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, (1866; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995), 97. ↵

- For an informative survey of contemporary writing (literature, natural history, and government reports) expressing misgivings about the destruction of trees and forests, see Sachs, Arcadian America, 137–209. Sachs argues that the Civil War posed the greatest challenge to date to the American Arcadian tradition. ↵

- Edmund Russell and Richard Tucker, “Introduction,” in Natural Enemy/Natural Ally: Toward an Environmental History of Warfare (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2004), 7. ↵

- For the cultural significance of domestic spaces ruined by the war, see Nelson, Ruin Nation, chap. 2. ↵

- Morton Keller, “The World of Thomas Nast,” (presentation, Celebrating Thomas Nast’s Contributions to American History and Culture, Ohio State University, December 7, 2002), reproduced at http://cartoons.osu.edu/nast/keller_web.htm (accessed August 2, 2012). See also Fiona Deans Halloran, Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). ↵

- Thaddeus Minshall to unidentified correspondents, November 26, 1862; and March 26,1863, in “‘This Terrible Conflict of the American People’: The Civil War Letters of Thaddeus Minshall,” ed. Lisa M. Brady, Ohio Valley History 4, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 12, 15. ↵

- Brady, War Upon the Land, esp. the conclusion (127–40). The wartime allusions to wilderness recall the colonial distrust of uncultivated land; see Roderick Nash’s classic study Wilderness and the American Mind, rev. ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977). ↵

- Paul S. Sutter, foreword to Brady, War Upon the Land, xiv. There are striking parallels between The Result of War and the final scene of Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire (1836; New-York Historical Society). ↵

- The drawing is reproduced without comment or identification in Albert Bigelow Paine, Th. Nast: His Period and His Pictures (New York: Macmillan Company, 1904), 91. Nast’s illustration appeared a few weeks after the battle at Gettysburg and may have served as a reminder that Confederate forces posed an active threat to Northern landscapes. Examples of decorated envelopes in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society that depict the punishment for treason/secession as hanging include “Arguments for Traitors,” “The Jeff. Davis’ ‘Neck-tie,’” “Good ‘Noose’ for Traitors,” and “Judas Vile Betrayed His Master.” ↵

- Robert Knox Sneden, January 24, 1862, as quoted in Images from the Storm: Private Robert Knox Sneden, eds. Charles F. Bryan, Jr., James C. Kelly, and Nelson D. Lankford (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 21. See Nelson, Ruin Nation, chap. 3, for other examples. ↵

- “Island No. 10—Incidents During the Siege,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 26, 1862, 390. ↵

- Thompson, The Image of War, 114. ↵

- David C. Miller, Dark Eden: The Swamp in Nineteenth-Century American Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 8. Miller notes that during the same mid-century period, a taste for unconventional landscapes, including the swamp, emerged; this taste would accelerate in the post-war years. He reads this shift as a rejection of the public, moralizing landscapes of the Hudson River School and a move toward landscapes that privileged subjective and aesthetic experience. ↵

- Ibid., 10. For further discussion, see Miller, Dark Eden, 56–57, 75, and chap. 3; see also Conevery Bolton Valencius, The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 145–52. Both Miller and Valencius comment on the complex associations between African Americans and the swamp during this period. ↵

- Brady, War Upon the Land, 15–16, and 27. Brady links the application of engineering solutions to military landscapes to many officers’ education at West Point. ↵

- For two prints by artists sympathetic to the Confederacy that also associate Southern forces with the landscape surrounding the Mississippi, see Adalbert Volck, Vicksburg Canal, 1864, and Frank Vizetelly, “Jefferson Thompson’s Guerillas Shooting at Federal Boats on the Mississippi,” Illustrated London News, June 14, 1862, 599. ↵

- The American Art-Union purchased the painting from Bingham in 1845 for its annual raffle; Maurice Bloch, George Caleb Bingham, vol. 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 110–11. For other images that link threatening landscapes with Native Americans, see Charles Deas, Death Struggle (1845; Shelburne Museum) and print version in 1846; George Caleb Bingham, Captured by Indians (1848; Saint Louis Art Museum); William Tylee Ranney’s two versions of The Trapper’s Last Shot (1850; University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library, and private collection) and lithograph by Currier and Ives, after 1855, as well as earlier variations on the theme such as John Vanderlyn’s Death of Jane McCrea (1804; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art). ↵

- Michael Edward Shapiro, “The River Paintings,” in George Caleb Bingham (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 1990), 149, and Nancy Rash, The Painting and Politics of George Caleb Bingham (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 45–46. ↵

- Henry Adams suggested that Bingham was following the example of Salvator Rosa’s sublime landscapes when creating the scene, thereby emphasizing the dangers of the early frontier. See Henry Adams, “A New Interpretation of Bingham’s Fur Traders Descending the Missouri,” Art Bulletin, 65, no. 4 (December 1983): 675–80. Adams was the first to argue that Bingham intended Fur Traders and The Concealed Enemy as pendants, representing the landscape traditions of Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa, respectively. ↵

- John Greenleaf Whittier, Justice and Expediency (1833), in The Works of Whittier, vol. 7 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1892), 33, as quoted in Sarah Burns, Pastoral Inventions: Rural Life in Nineteenth-Century American Art and Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), 83–85. Burns traces the links between abolitionist rhetoric and images of a diseased South. ↵

- The etching appeared in Forbes’ self-published series entitled Life Studies of the Great Army, 1876. According to the historians Mark Neely and Harold Holzer, Forbes chose the etching medium for his series because of its elevated, fine art associations, but he tapped into a sense of Northern struggle against nature also found in popular culture; see Mark E. Neely, Jr. and Harold Holzer, The Union Image: Popular Prints of the Civil War North (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 77. See also William Forrest Dawson, ed., A Civil War Artist at the Front: Edwin Forbes’ Life Studies of the Great Army (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957). ↵

- Edwin Forbes, Thirty Years After: An Artist’s Memoir of the War, with an introduction by William J. Cooper, Jr. (1890; reprint, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993), 210. Forbes gives the date of the march as late 1863, but it occurred in January of that year. ↵

- John Beauchamp Jones, diary, January 29, 1863, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1866), 248. ↵

- There is some uncertainty surrounding the attribution of this illustration. The Newberry Library’s copy of Leslie’s identifies C. E. H. Hillen as the artist in the caption; the copy of Leslie’s microfilmed by the Illustrated Civil War Newspapers and Magazines database (Alexander Street Press) identifies the artist as C. E. H. Bonwill in the caption. Hillen seems to be the correct creator, since he submitted other illustrations from Tennessee during the same period. To add to the confusion, Harry L. Katz and Vincent Virga write that there were two artists with the name Hillen working for Leslie’s at the same time who were probably related: John F. E. Hillen and C. E. F. Hillen; see Civil War Sketchbook: Drawings from the Battlefront (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), xxi. ↵

- “Rebel Pickets Disguised in Cedar Bushes,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper December 12, 1863, 189. ↵

- For other examples from the Northern press, see Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 12, 1861, 343; June 28, 1862, 193; and December 3, 1864, 164; and Harper’s Weekly, November 2, 1861, 694; February 8, 1862, 81;February 14, 1863, 97; and May 9, 1863, 289. From the Southern press, see Southern Illustrated News, January 24, 1863, 1, and March 7, 1863, 5; and Southern Punch, September 26, 1863, 4. ↵

- “The Picket-Guard,” Harper’s Weekly, November 30, 1861, 766. ↵

- Timothy Sweet emphasizes the divergent messages of Melville and the war photographers, yet there are parallels between his poetry and the visual culture of the war. See Timothy Sweet, Traces of War: Poetry, Photography, and the Crisis of the Union (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), chap. 6. ↵

- Herman Melville, “The Scout Toward Aldie,” in Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, (1866; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995), 187. ↵

- Ibid., 188, 198. ↵

- Ibid., 219. ↵

- Although beyond the scope of this essay, Forbes’ print bears comparison with Eastman Johnson’s painting, A Ride for Liberty—The Fugitive Slaves, (c. 1862; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts). Both images depict an African American family within an expressive landscape, but Johnson gives much more agency to his figures through his depiction of their active attempt at emancipation. For the nuances of Johnson’s depictions of African American figures, see Patricia Hills, “Painting Race: Eastman Johnson’s Pictures of Slaves, Ex-Slaves, and Freedmen,” in Teresa A. Carbone and Patricia Hills, Eastman Johnson: Painting America (New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1999), 121–65. ↵

- Forbes, Thirty Years After, 317. ↵

- For an introduction to Northern period images and texts about contrabands, see Lucia Z. Knowles, “Slaves Declared Contrabands of War,” in Northern Visions of Race, Region, and Reform, a website sponsored by the American Antiquarian Society, http://faculty.assumption.edu/aas/intros/contrabands.html (accessed August 23, 2012). ↵

- For the complicated history of the term “contraband,” see Kate Masur, “‘A Rare Phenomenon of Philological Vegetation’: The Word ‘Contraband’ and the Meanings of Emancipation in the United States,” Journal of American History 93, no. 4 (March 2007): 1050–84. ↵

- Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer point out the significance of the mobility depicted in representations of contrabands in Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013), 64–65. ↵

- Amy Murrell Taylor, “A War of Words,” The Front Line blog, Civil War Monitor, September 29, 2011, http://civilwarmonitor.com/front-line/a-war-of-words (accessed September 5, 2012). ↵

- Sources on the Freedman’s Village include Roberta Schildt, “Freedman’s Village: Arlington, Virginia, 1863–1900,”Arlington Historical Magazine 7, no. 4 (October 1984): 11–21, and Joseph P. Reidy, “Coming from the Shadow of the Past: The Transition from Slavery to Freedom at Freedmen’s Village, 1863–1869,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 95, no. 4 (October 1987): 403–28. ↵

- “Freedman’s Village, Arlington Virginia,” Harper’s Weekly, May 7, 1864, 294. ↵

- Ibid. Reidy, “Coming from the Shadow,” 407–8, discusses the government’s prescribed work ethic for the former slaves. ↵

- See Schildt, “Freedman’s Village,”17–19, and Reidy, “Coming from the Shadow,” 413–21. ↵

- Forbes’ other contraband images include two additional etchings from The Life Studies of the Great Army: Coming into the Lines and The Reliable Contraband. These two images also appear in Forbes’ Thirty Years After (235 and 291, respectively). ↵

- See Cikovsky, “Winslow Homer’s ‘Prisoners from the Front,’” 161–65, in which the author argues that Homer fused the battlefield of Petersburg, which he had sketched (see fig. 11), with reports of the surrender of thousands of Confederate soldiers to Barlow at Spotsylvania. Charles Colbert provides another link to Petersburg in identifying the youngest Confederate in Prisoners from the Front as the same figure in Homer’s painting Defiance: Inviting a Shot before Petersburg, Virginia (1864; Detroit Institute of Arts); see Colbert, “Winslow Homer’s Prisoners from the Front,” American Art 12, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 66–69. ↵

- Another prominent example of the use of pine branches occurs in the memorial equestrian portrait of William Tecumseh Sherman by Augustus St. Gaudens (1903; Grand Army Plaza, New York). In the Sherman memorial, the triumphalism is explicit; the horse tramples pine branches in order to signify the general’s march across Georgia. ↵

- I am grateful to Sarah Burns for pointing this out. ↵

- Dawson, A Civil War Artist at the Front, text with pl. 20. ↵

- Much of the scholarship on Homer’s painting has focused on the way it defied classification according to traditional painting genres. See, for example, Lucretia H. Giese, “Prisoners from the Front: An American History Painting?” in Simpson, Winslow Homer: Paintings of the Civil War, 65–81; Mark Thistlethwaite, “A Fall from Grace: The Critical Reception of History Painting, 1875–1925,” in Picturing History: American Painting, 1770–1930, ed. William Ayres (New York: Rizzoli, in association with the Fraunces Tavern Museum, 1993), 180–82; Conn and Walker, “The History in the Art”; and Steven Conn, “Narrative Trauma and Civil War History Painting, or Why Are These Pictures so Terrible?” History and Theory 41, no. 4 (December 2002): 37–42. ↵

- See Simpson, Winslow Homer: Paintings of the Civil War, 255–59, for reprints of reviews that appeared prior to 1876. ↵

- Examples include commentary in the New York Evening Post, April 28, 1866, and Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, June 1866. See Simpson, Winslow Homer: Paintings of the Civil War, 256, 258. ↵

- Miller, “Albert Bierstadt,” 40. See also Harvey The Civil War and American Art on the western landscape as a possible national sanctuary, 60–62. ↵

- Kevin Avery draws parallels between Gifford’s Hunter Mountain, Twilight, and Homer’s Prisoners from the Front, both of which were exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1866. See Kevin Avery, “Gifford and the Catskills,” Hudson River School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford, eds. Kevin J. Avery and Franklin Kelly (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 44–45. See also Sachs, Arcadian America, 141–44. On the illustrations, see Janice Simon, “Reenvisioning ‘This Well-Wooded Land,’” in Seeing High and Low: Representing Social Conflict in American Visual Culture, ed. Patricia Johnston (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), esp. 150–53. ↵

About the Author(s): Maura Lyons is at Drake University.

![Fig. 2 Ebenezer Mix, The Pioneer Settler: First Scene. From O[rsamus] Turner, Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York, Buffalo, N.Y., 1849. Engraving. (Newberry Library, Chicago.)](https://journalpanorama.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Figure2_Mix-300x175.jpg)