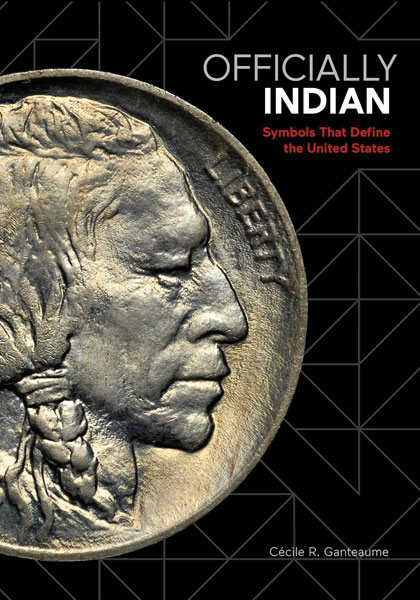

Officially Indian: Symbols That Define the United States

Cécile R. Ganteaume

Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 2017; 192 pp.; 50 color illus.; ISBN: 978-1-5179-0330-5; Hardcover: $28.00

Exhibition schedule: Americans, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, January 18, 2018–2022

In Officially Indian: Symbols That Define the United States, Cécile Ganteaume examines five centuries of official and semi-official visual and material depictions of Native Americans.1 The book is structured as extended essays for each of its forty-six chosen objects, with two guest essays by historian Colin G. Calloway and cultural critic Paul Chaat Smith, as well as a substantive introduction by Ganteaume.

In Officially Indian: Symbols That Define the United States, Cécile Ganteaume examines five centuries of official and semi-official visual and material depictions of Native Americans.1 The book is structured as extended essays for each of its forty-six chosen objects, with two guest essays by historian Colin G. Calloway and cultural critic Paul Chaat Smith, as well as a substantive introduction by Ganteaume.

Officially Indian accompanies the newly opened Americans exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC, which Ganteaume co-curated with Smith (fig. 1). It also has an online component that can be used for teaching. The exhibition tackles the profound irony that Native American images, names, and stories proliferate in the United States, while indigenous people themselves only make up one percent of the US population. To explore this irony, three chapters of the nation’s founding narrative are plumbed in depth: the life of Pocahontas, the Trail of Tears, and the Battle of Little Bighorn. These thematic sections demonstrate how Native American histories have always been entangled with the development of the United States, and how indigenous people have served as a central visual emblem for the country.

While the exhibition takes on popular culture and founding myths, Ganteaume limits her narrative in Officially Indian to the relationship between Native Americans and the formal nation-state. The featured objects in the book fit within a narrower frame of official US-sponsored emblems, although some predate the establishment of the United States in 1776, and others, such as the 1889 membership certificate for the fraternal organization of the Improved Order of the Red Men, fall under a semi-official rubric of activities associated with public figures. The range of time periods and object types is impressive, stretching from sixteenth-century cartographic cartouches on European maps to contemporary cast-glass windows in the Library of Congress.

Ganteaume’s argument, as described in her introduction, is that indigenous people have been core to American democratic ideals and the national debates over what these ideals mean. The fact that Native Americans have never disappeared from official US imagery bears this argument out, as does its long historical trajectory. North American colonists inherited centuries-old ideas, visual representations, and diplomatic relationships from European leaders, who had necessarily shaped their various North American strategies around (and at times with) the dominant indigenous populations of the Americas. The chosen objects in the book, presented in chronological order, reconstruct this long and constantly changing relationship between indigenous people and American democracy in visual and material form.

This approach, with its focus on democratic ideals, leads to a different narrative than the art histories that have tackled these issues before. Ganteaume intentionally bypasses an analysis of well-rehearsed tropes, such as the “noble savage” or the “vanishing Indian,” in favor of deeply contextual and historical analysis focused on state-sanctioned activities. The narrative also foregoes period-specific analytic lenses, such as using “ethnographic” to describe artists’ framings of Native American subjects in the nineteenth century. What ties the chosen objects together are official decisions, activities, and commissions, rather than stereotypes or artists’ intentions. What were officials thinking in 1904, for instance, when sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was hired to create a coin featuring Liberty in a Plains Indian eagle-feather headdress? Or in 1939, when officials commissioned California painter Louis Siegriest to design posters for the Indian Court exhibition in the US pavilion at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition?

This approach has several benefits in linking particular historical moments with various artistic and official choices. For instance, throughout the text, Native Americans are repeatedly depicted in feather headdresses. In the first object essay, Ganteaume locates the origin of this common motif in the historical contacts between Brazilian Tupinambá people and the Italian explorer and cartographer Amerigo Vespucci along coastal Brazil in 1501 and 1502 (26–27). Later, in discussing the peace medal commissioned under George Washington to be given to Native American leaders, Ganteaume reminds readers that Washington would have known that the depiction of an indigenous man wearing Tupinambá dress on the medal did not resemble the clothing worn by the Native American contemporaries of the president (67).

In providing such historical punctures and intersections with various objects, Ganteaume reminds readers that more than philosophical ideas or visual depictions were present in early America—that indigenous people themselves have served as living, breathing points of reference for many official depictions over the centuries. Furthermore, previous interpretations of such continued imagery as trope resulted in flattened readings, whereby continuations of visual elements happen through artistic and visual inheritance. Here, however, each appearance takes on the weight of new political conditions and frameworks that influence choice and deployment—an approach that incorporates the relational model of national identity and Native Americans put forward by historian Philip J. Deloria, whereby the position of indigenous people in relation to a national culture continually changes based on political and cultural conditions.2

Employing such a model opens onto the continual entanglement of Native American and American histories, and these entangled histories undergird both Ganteaume’s text and the larger related NMAI exhibition, as signaled by the exhibition title: the term “American” was first coined after the previously mentioned venture of Amerigo Vespucci to describe the indigenous inhabitants of the continent. Only centuries later did the term become a distinct designation for residents of the British colony and subsequently formed nation-state. Exactly how the term applies to native people of the United States is still in process, as “American Indians and the United States have been working out, in one fashion or another, the status of their unique relationship, and they have been working out just how the United States’ most cherished values of liberty and equality apply to Native nations” (19). The collected objects and essays in Officially Indian highlight just how fraught and ever-changing this working out has been.

Those teaching high school students, undergraduates, or museum audiences will benefit from the short essay formats, as each object essay is written independently of the rest—one can easily tailor the text to one’s teaching or to an institutional collection. Others will find that the short essay approach is a drawback, as each entry, which is careful to include the most basic information in each one for standalone use, can read as repetitive when the book is taken as a whole. The text does not build a larger argument over its pages; the essays instead present the evidence for the arguments summarized in the introduction. The exhaustive references section also would have benefited from annotations in order to make it more useful to teachers and researchers who want to explore further the book’s particular histories, works, and themes. This is therefore not a graduate student or strictly academic text, but one designed for both general public and educator audiences. One can hope that the NMAI will commission a more scholarly component for their ambitious exhibition at a later date, to take up the broader implications that their entangled methodology presents for a variety of academic disciplines, including that of American art history.

In a time when relationships between indigenous communities and nation-state governments are radically changing in North America, the arguments of Officially Indian and its contemporary dynamics are particularly important to rethink and recategorize. At the time of this writing, the Trudeau government in Canada has issued many directives to expand indigenous presence in universities and governments. “Reconciliation” is a common topic among Canadians, and students pursue courses in indigenous studies as part of their own personal efforts to understand and engage with decolonization processes. In the United States, the Trump administration shrank Bears Ears Monument in a single government-issued memorandum, disregarding its shared management arrangement with five area tribes. Such turns of events and their rhetoric serve as reminders of the fluid and still-in-process nature of North American official relationships to its many indigenous peoples. Ganteaume’s book is a needed and helpful text that can begin to push these dialogues into our classrooms in a more complete, historical, and entangled fashion.

Cite this article: Kristine Ronan, review of Officially Indian: Symbols That Define the United States, by Cécile R. Gantaume, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1644.

PDF: Ronan, review of Officially Indian

About the Author(s): Kristine K. Ronan is Visiting Assistant Professor at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.