Pacita Abad

PDF: Vigneault, review of Pacita Abad

Curated by: Victoria Sung, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

Exhibition schedule: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, April 15–September 3, 2023; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, October 21, 2023–January 28, 2024; MoMA PS1, New York, April 4–September 2, 2024; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 9, 2024–January 19, 2025.

Exhibition catalogue: Victoria Sung, ed., Pacita Abad, exh. cat. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2023. 352 pp.; 344 color illus.; 80 b/w illus. Cloth: $65.00 (ISBN: 97819359663264)

Pacita Abad (1946–2004) created her first trapunto (a stuffed and quilted painting) in 1981. At the time, Abad was living in Boston and meeting weekly with a group of women artists, including Joanna Kao and Barbara Johansen Newman, whose work would prove deeply influential in both material and political ways to Abad’s rapidly expanding artistic process. Abad was still relatively new to the contemporary art scene in the early 1980s; she enrolled in her first formal art class at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, DC, in 1974, only a year after earning a master’s degree in history at Lone Mountain College in San Francisco and being accepted into law school at the University of California, Berkeley.1 Born in the Philippines to politically active parents, Abad had moved to the United States in 1970, in large part to escape the rampantly corrupt and unstable rule of Ferdinand Marcos, whose government she often protested as part of student-led demonstrations in the late 1960s. Abad found in early 1970s San Francisco an equally politically active environment in which she could connect the abstract knowledge of her undergraduate degree in political science with her deeply empathetic care for and interest in the various communities of Bay Area immigrants, refugees, and transplants. It is not surprising, then, that when Abad turned to making visual art in the mid-1970s, she focused on politically current subjects, with an eye toward her own identity as an outsider looking in. Yet, it is shocking is that the current traveling exhibition of Abad’s multimedia artwork, simply titled Pacita Abad, marks the first-ever retrospective of this extraordinary artist (the accompanying catalogue is also the first major publication on Abad), a reminder of just how much feminist (art-historical) homework remains to be done.

At MoMA PS1, where I experienced the exhibition, fifty-five artworks—ranging from trapuntos to a welded-steel door, to drawings, prints, and paper assemblages—and one video were on view. This display was a small but representative sliver of Abad’s prolific artistic output, estimated at five thousand pieces made over a thirty-two-year career. While other exhibition venues incorporated a more robust checklist (for instance, the Ontario Museum of Art’s showing includes more than one hundred objects, including ornamented utilitarian objects and the clothing and costumes Abad made for herself and others), I imagine the architectural limitations of PS1, housed in a neo-Romanesque building constructed as a public school in 1892, in part explain the reduced number of works on views in New York. Yet, this scaling down in no way resulted in a scaled-down experience. The entrance to the exhibition, in one of the largest rooms at PS1, evoked a sense of awe (impossible to capture no matter how I positioned myself or my cellphone camera, but I still tried; fig. 1).

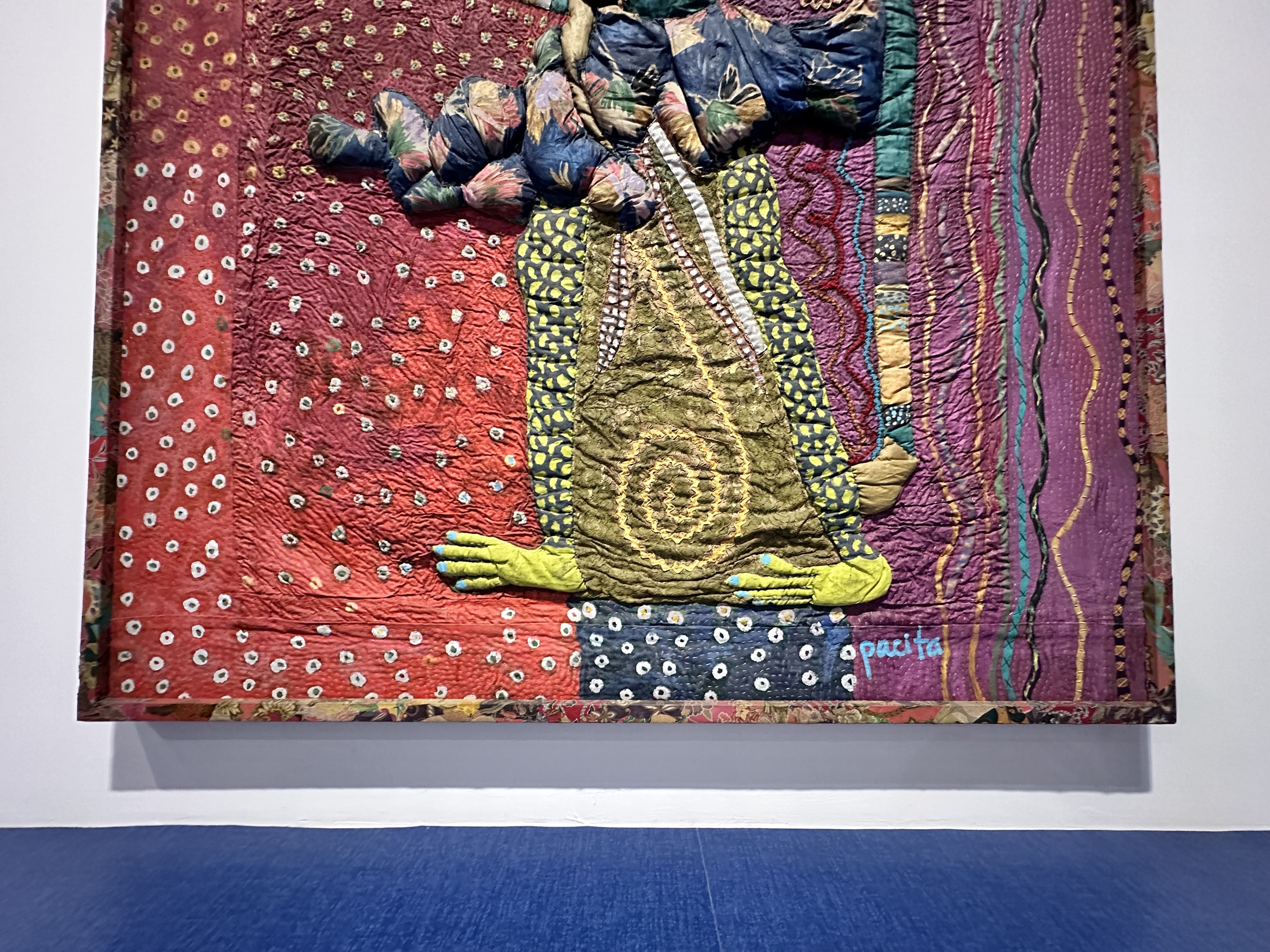

I think this sense of awe stemmed from seeing Abad’s work in person, in all its tactile presentness, when I had previously only viewed digital versions small enough to fit on my tablet or phone screen. In person, Abad’s work pops, quite literally, off the walls. The stitching in the trapuntos both cloisters and puckers areas of collaged and wrapped fabric (fig. 2; note the vibe of the blue toenails Abad matched to her signature), creating clear aesthetic connections to the Pattern and Decoration artists of the late 1970s and early 1980s, as well as to the work of Harmony Hammond, who refers to her own practice of painting fabric pieces as “expanded painting.”2 Faith Ringgold’s painted story quilts, which she called paintings in the medium of quilting, are also part of this expanded field of art making. I am reminded, too, of the conceptual artist Kimsooja’s early 1980s stitched pieces, in which embroidery meanders across painted cloth surfaces, evoking the domestic and its affiliate, the feminine.3 These artists converted the practices so often devalued as “women’s work” into valued artwork, subversively amplifying the voices and stories of those veiled by historical narratives of the other, the outsider, the foreigner.

Abad’s stitched trapuntos puncture the veil of oppression—the word trapunto, in fact, derives from the Italian trapungere (to embroider) and the Latin pungere (to prick or puncture)—exposing the radiant and vivacious presence of everything everywhere, all at once. Abad’s trapuntos are brilliant in both senses of the word: the surfaces are bright and luminous, sunbursts of color pierced with miniature mirrors, beads, shells, and sequins. They are also clever and intelligent, the products of a relentlessly curious and creative mind committed to visualizing the interconnectedness of colonialism, globalization, gender discrimination, labor rights, and immigration. Abad rendered brilliant surfaces that draw viewers into the works and then keep them looking. While these brilliant trapuntos are beautiful, the subjects themselves disrupt any initial pleasure that comes from pure aesthetic appreciation. This was my experience when viewing Caught at the Border (fig. 3), with its surface of stitched-on mirrors and sequins that caught my eye from across the gallery. At a distance, the swirling patterns in grays, blacks, and blues appear decorative and abstract; up close, they are stifling and impenetrable, as the woven ribbons of painted barbed wire come into focus. The push/pull tension, both visual and psychological, frames the central figure, whose face is veiled by a sharp grid of painted lines that only partially obscure his eyes. He sees us; we see him. But what can we do? There is a hopelessness in both of our positions, yet I can walk away. While Abad created Caught at the Border in 1991, in response to the detention at the US-Mexico border of tens of thousands of Central Americans fleeing political violence (echoing Abad’s own escape to the United States in 1970), the significance of the subject and the unfortunate timelessness of the scene registers this trapunto in the here and now. US border policy is still at the forefront of the 2024 presidential election; politicians continue to make false claims about migrant crime waves; yet it is actually most often the immigrants themselves who are subject to discriminatory and threatening behavior. I can walk away, but that glint of barbed wire stays in my eye.

Caught at the Border was displayed next to another trapunto, Girls in Ermita (fig. 3), whose vibrant reds and yellows contrast with the despairing coolness of Caught at the Border. Yet, these works are deeply connected, as both make visible the abuse of bodies, particularly of people who exist in the lower levels of a globalized society, by outside powers who maintain their control via the levers of patriarchal and capitalist exploitation. Ermita is a red-light district in Manila that still largely caters to foreigners (almost all of the signage in the trapunto is in English), a fantasy mix of “New Bangkok” and “Old Vienna.” In other words, it is a place both real and unreal, a purgatory fenced in by neon lights that function as their own form of barbed wire. Abad had moved temporarily back to Manila in the early 1980s, and her imaging of the spectacle of Ermita, a “lost Eden” according to one of the marquees, is a visual collision of what she saw and what she heard about the place, where women in bikinis and heels were positioned as nothing more than objects to be used by (almost exclusively) men. While Girls in Ermita offers a peek into the dark underside of Manila’s streets, it is the brilliant curatorial choice to pair this trapunto with Caught at the Border, which allows us to actually look, not just peek, at the underlying thread of Abad’s work: political exploitation. It is patriarchal capitalism that dictates how bodies are used and who gets to use those bodies, that decides whose bodies are granted freedom of movement and whose are imprisoned behind barbed wire, both of spiked metal and flashing neon.

Caught at the Border is part of Abad’s Immigrant Experience series (1983–95), in which she emphasizes the humanity of individuals stereotyped and often demonized by media headlines focused on riots, crises, and detentions. Abad transmutes the black-and-white text of newspapers into vivaciously ornamented trapuntos that more often than not proclaim the immigrant experience as celebratory and colorful, an aesthetic decision that, as Julia Bryan-Wilson notes in the exhibition catalogue, is “vital to her political and material approach as a feminist immigrant artist of color.”4

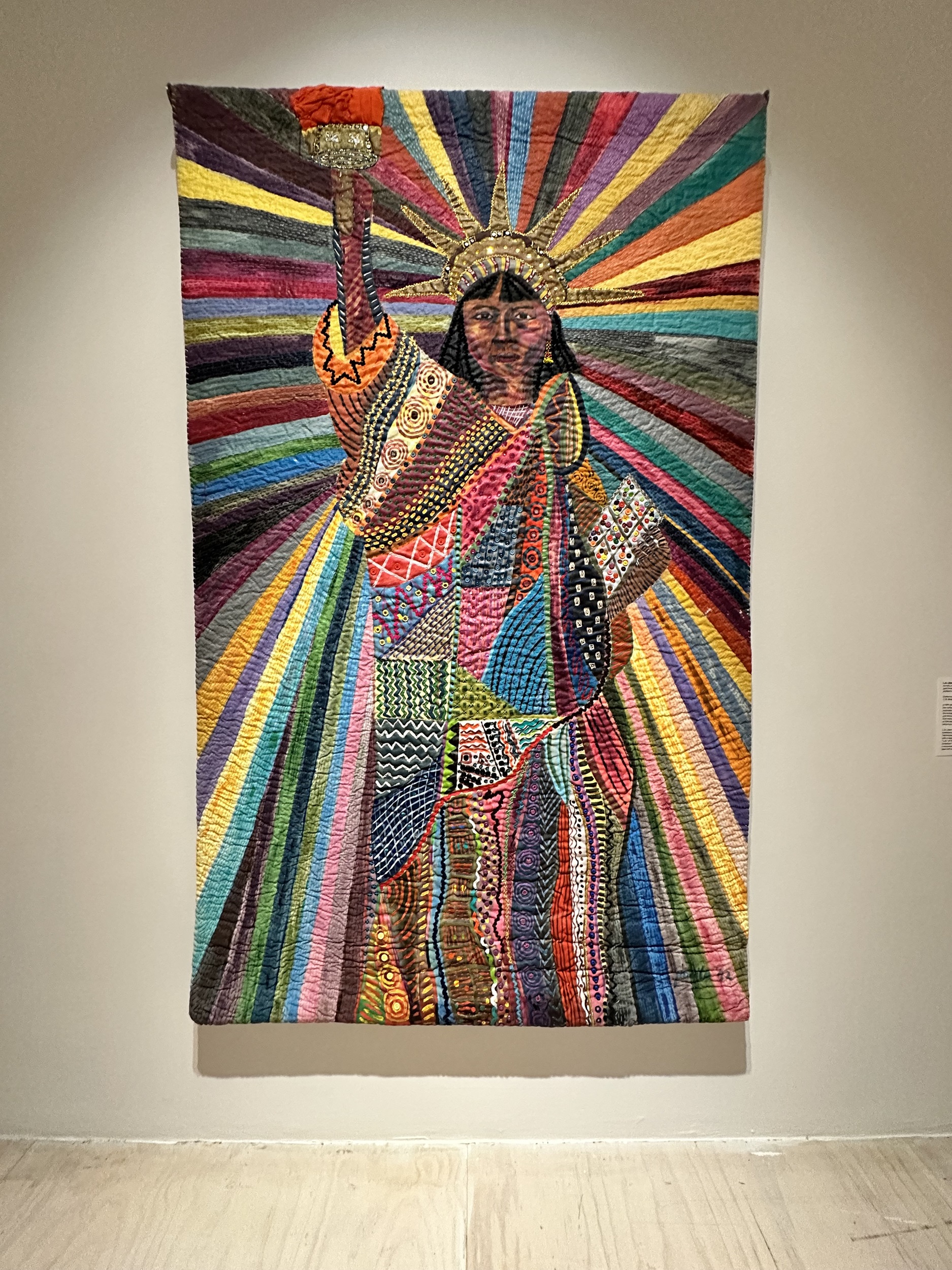

Abad entered the United States on the West Coast, which has a markedly different history from the Northeast, where millions of mostly white European immigrants passed the Statue of Liberty on their way to governmental processing at Ellis Island between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth century. No equivalent symbolic point of entry or massive welcoming statue existed for Abad or the millions of other immigrants of color who arrived anywhere but New York. So Abad made her own: L.A. Liberty (fig. 4), a radiantly prismatic trapunto that simultaneously celebrates Indigenous, Latin American, and Asian American presence and critically disrupts the mythmaking of the United States as a place for the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” proffered by the monochromatic Statue of Liberty.5 It is notable that Abad made this work in 1992, the year of the Los Angeles Uprising, which was in large part set off by the acquittal of four Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers charged with using excessive force on Rodney King, although tensions between the LAPD and minoritized communities, particularly around racial profiling, were already well established. 1992 is also the year of the first Bush administration’s Kennebunkport Order, which forcibly repatriated thousands of refugees seeking asylum in the United States back to wartorn Haiti.6 The media rhetoric at the time revived the Center for Disease Control’s discriminatory “Four H” group—those identified as most at risk of carrying and spreading the AIDS virus: homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitians—as justification for the government’s actions, a gross stereotyping and scapegoating of an ethnonational group that finds a present equivalent in Donald Trump and J. D. Vance’s flat-out lies accusing Haitian immigrants of eating people’s pets and being the cause of rising HIV and tuberculosis rates.7 Ideological battles over immigration, globalization, and cultural assimilation have long been a part of US politics, but as the works in the PS1 exhibition reminded us, these subjects remain as central to our contemporary climate as they were decades ago. Although Victoria Sung’s curatorial vision for a retrospective of Abad’s work predates election-cycle spin, I could easily believe that the work was purposefully chosen and installed to counter the misogynistic and anti-immigrant statements we continue to hear, which is exactly in line with how Abad viewed the role of the artist: “I have always believed that an artist has a special obligation to remind society of its social responsibility.”8 We have been reminded; we must now take action.

Abad led an extraordinary life, one infused with curiosity about herself and the world around her, which she soaked up like color staining raw cloth. She was, as Bryan-Wilson describes her, “visually ‘loud,’” which functioned as a type of armor “in the face of repressive systems that wish to mute, dampen, or even erase one’s presence.”9 Abad’s “loudness” extended from her person to the world around her, resulting in a cross-weaving of life in which everything was art, and art was everything. What this retrospective of Abad’s work ultimately asks us to recall is Abad’s embrace of humanity and her insistence on interconnectedness, even in the face of our worst tendencies. This is the core brilliance of her work—its multidimensionality—in which each subversive stitch is ultimately sewn together as an embroidery of resilience.

Cite this article: Marissa Vigneault, review of Pacita Abad, MoMA PS1, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19310.

Notes

- The Walker Art Center compiled a robust chronology of Abad’s life for the exhibition catalogue; it is also available online: Matthew Villar Miranda, comp., “Chronology of the Life and Work of Pacita Abad,” Walker Art Center, accessed October 22, 2024, https://walkerart.org/magazine/chronology-of-the-life-of-pacita-abad. ↵

- Clarity Haynes, “Going Beneath the Surface: For 50 Years, Harmony Hammond’s Art and Activism Has Championed Queer Women,” ARTnews, June 27, 2019, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/harmony-hammond-12855. ↵

- “It is not only home and family that embroidery signifies, but, specifically, mothers and daughters.” Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (London: Women’s Press, 1984), 2. ↵

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Pattern as Politics,” in Pacita Abad, ed. Victoria Sung, exh. cat. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2023), 272. ↵

- This famous line inscribed on the statue is from Emma Lazarus’s 1883 poem “The New Colossus.” ↵

- Both George H. W. Bush’s and Bill Clinton’s administrations forcibly detained Haitian migrants at Guantanamo Bay in the 1990s. ↵

- Christopher Wiggins, “JD Vance now says Haitian Immigrants are spreading HIV after bizarre pet-eating claim flops,” Advocate, September 13, 2024, https://www.advocate.com/election/jd-vance-haitian-hiv-stigma. ↵

- Abad, quoted on the exhibition website, MoMA PS1, accessed October 22, 2024, https://www.momaps1.org/en/programs/359-pacita-abad. ↵

- Bryan-Wilson, “Pattern as Politics,” 281. ↵

About the Author(s): Marissa Vigneault is associate professor of art history at Utah State University