Pos(t)ing Online, or the Other Side of the Glass for Looking

PDF: Vigneault, Pos(t)ing Online

Who are you? everybody in Through the Looking-Glass asks Alice.

But Alice cannot remember. Alice is a certain kind of AI,

let’s call her a girl-function: an eternal question . . .

A girl online is an Alician subject.

—Joanna Walsh1

Let me pose a question: What is at stake when a female artist poses?2 I am certainly not the first to ask this question, central to decades of feminist art-historical revisions and revisitations. But, let me propose that the stakes of posing in the twenty-first century have significantly shifted what it means for the female artist to produce and consume images of herself. In our contemporary existence, filled with images, chats, and deepfakes generated by artificial intelligence (AI), as well as an ever-expanding blur between online and offline (or away from keyboard [AFK]) worlds, the screen has become the ultimate mediator; it is the looking glass (or “glass for looking,” as named by Joanna Walsh) that prompts us, like Alice, to wonder what wonderland lies beyond.3 In wondering what is at stake when a female artist poses, we also have to ask what is at stake when we consume these images online through a screen. For to pose online is, in a sense, to post, and posing and posting propose a whole new set of questions in regard to the production and consumption of female bodies.

To pose, as Mary Ann Doane theorizes in relation to female bodies on film, is to take a position.4 It is also, in her theoretical positioning, a way to foreground what is at stake when one poses the body. A posed body is always simultaneously a composition, an affect, a declaration, a question, and, above all, the thing at stake (at risk). This is deeply familiar territory for female artists who recognize that their bodies are never fully their own; even self-imaging bears the weight of vulnerability. But this is what Doane means by “stake,” for what is at stake (at risk) when a female artist poses is her body and, by extension, what that body means and how that body means under the cultural-temporal terms of its production. In this essay, I will focus on work by two female artists whose practice is marked by self-imaging, Hannah Wilke and Erin M. Riley, one historical and one working today, as a way to think through how the stakes of pos(t)ing shift when such images are consumed through contemporary media, such as a phone screen or a tablet or whatever device you are reading these words on right now.5 While it may initially seem anachronistic to consider Wilke’s 1970s performance work in relation to an online world that only really took off in the mid-1990s (America went online with AOL starting in September 1993), I posit that current engagement with Wilke’s work often takes place online and thus shapes our understanding of the stakes of her art right now. We cannot separate, then, what it means to encounter self-produced images (selfies) of Wilke, as well as Riley, online from everything else we experience in the space both on and beyond the screen.

Artist Ann Hirsch notes, “When we put our bodies online, we are in direct dialogue with porn,” meaning that a female body viewed online is always already infected by the medium.6 The scopic structure of pornography relies on an object ready for consumption, therefore, if images of female (artists’) bodies online are always “in conversation with porn,” then they are also always denied subjectivity. That is, under the patriarchal terms of pornification, a female artist never produces images herself; rather, the production of her image is a thing done to her (a conversion without conversation) so that her images may be parasitically consumed by another.7 How, then, can the female artist who produces images of herself subvert the constrictive space of pornification in assertion of her own desires? (In Doane’s formulation: “How can she speak?”)8 What are the strategies, both employed and employable, that permit other routes of engagement? For Doane, the pose (the performative position) is one such strategy, which may be used by the female artist as a “new syntax,” that is a new set of rules, “thus ‘speaking’ the female body differently, even haltingly or inarticulately from the perspective of a classical syntax.”9 Also relevant is Craig Owens’s correlation of the pose to the reflexive middle voice, whereby, working from a Lacanian perspective, “the subject poses as an object in order to be a subject.”10 To Doane’s and Owens’s significant thinking of the pose as strategy, I want to add a more contemporary consideration, that of the glitch, which is not a contemporary term but rather a contemporary strategy, as proposed by Legacy Russell. A glitch—“an error, a mistake, a failure to function . . . an indicator of something having gone wrong”11—is precisely what halts and makes inarticulate the “classical syntax” of the female body, thereby redirecting away from pornified consumption and toward “autonomous symbolic representation.”12

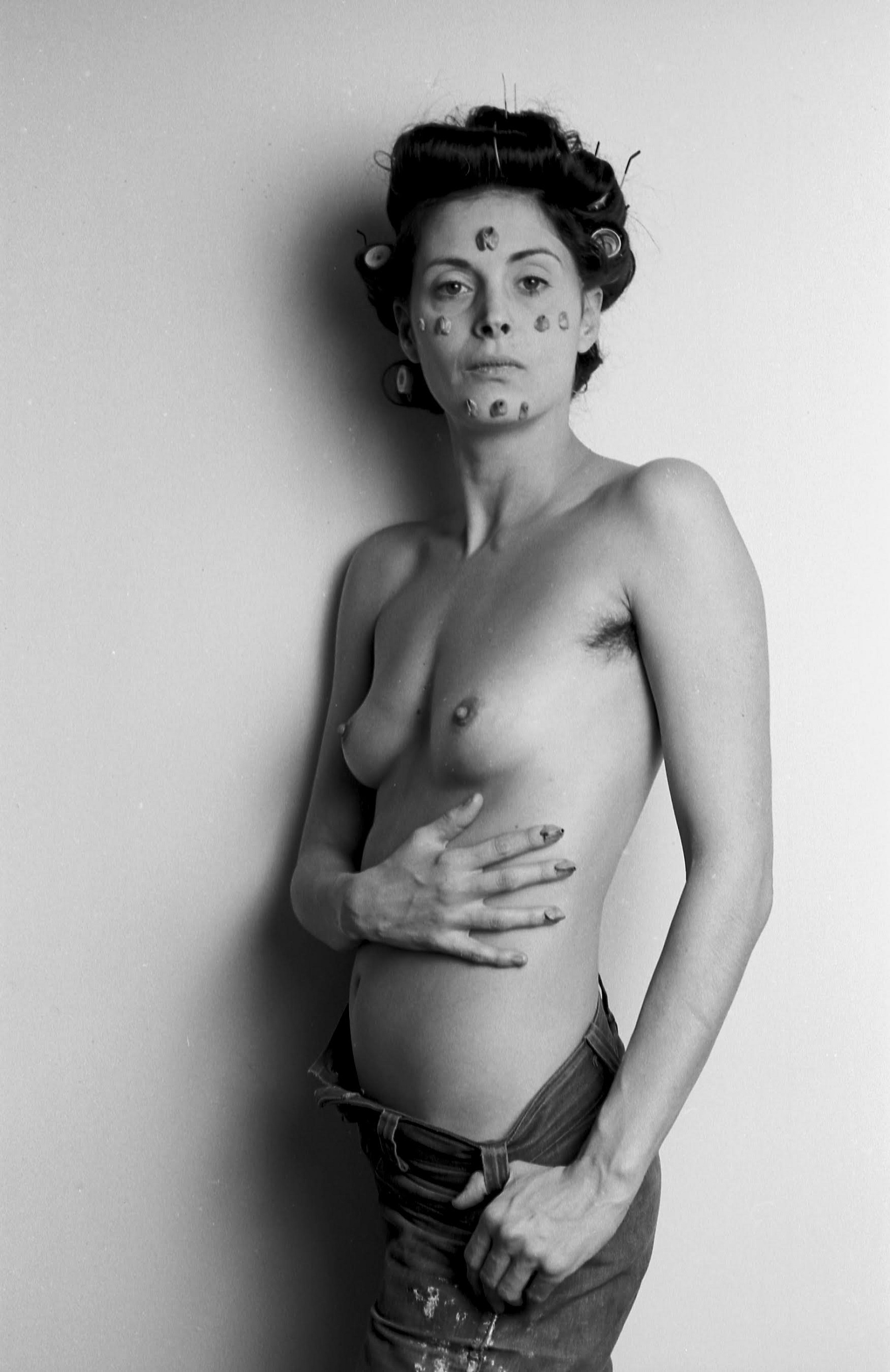

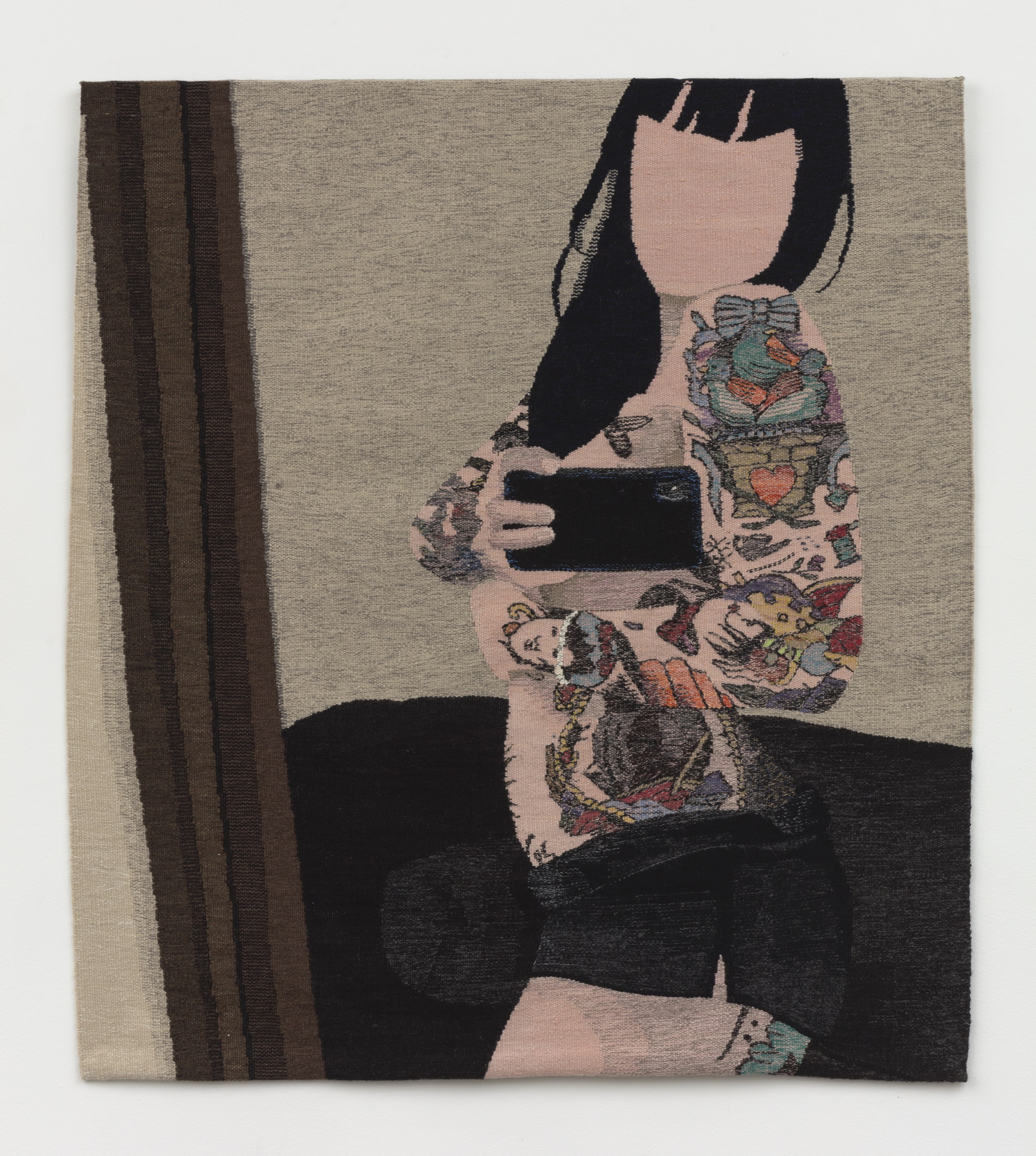

I start with two artworks to examine the pose and the glitch as feminist strategies: a small photograph made by Hannah Wilke in 1974, which she used as a game card in her S.O.S. Starification Object Series, An Adult Game of Mastication, and a large tapestry titled Nudes 41 woven by Erin M. Riley in 2020 during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, by which she converted one of her digital “nudes” into an analog textile (figs. 1, 2).13 The size of Wilke’s number 40 S.O.S. photograph/ game card, now framed but originally meant to be held in the hand, is, at 7 x 5 inches, slightly larger than the cell phone held in Riley’s hand in Nudes 41, connecting the two works via a scaling of intimacy and a suggestion of the haptic. The sense of touch is furthered by the positioning of the artists’ hands: Wilke loops her left thumb through the waistband of her pants while her right hand rests on her ribcage, fingers splayed to frame her left breast; Riley similarly wraps her left hand across her exposed torso while her right hand grasps the edges of her cell phone. Both S.O.S. and Nudes 41 are, at some level, selfies, though Wilke’s work predates the actual term; she referred to the S.O.S. series as “performalist self-portraits.”14 Riley’s work, on the other hand, is fully steeped in, and engaged with, the discourse around selfie culture that has marked so much debate on female self-imaging online since the mid-2010s.15 Despite the differences in time and terminology, Wilke and Riley both enact the self(ie) pose as performative, which speaks to Owen’s claims that “posing . . . is a form of mimicry” and that “mimicry has been especially valuable as a feminist strategy.”16 Mimicry, here defined as a deliberate imitation of feminine mannerisms, is thus understood as a powerful tool for the female artist who aims to critically disrupt the “classical syntax” of the female body. Mimicry underscores that the pose is always an imitation, a masquerade, and therefore there is no authentic body or even self that can be taken away. To this we need to add Luce Irigaray’s caveat that mimicry is perhaps women’s only option to speak within patriarchy but is only “valuable as a feminist strategy” if it fails.17

It is at this juncture of pose and mimicry that failure must enter the equation in order to function as feminist strategy. So, we have two things at play: first, the language of women in the AFK world, that of mimicry; and second, the potential language of girls online, the glitch, which we have already identified as a type of failure. Looking again at S.O.S. and Nudes 41, we see both Wilke and Riley mimic the feminine posturing favored by the culture industry and the sex industry, wherein female bodies are framed for easy consumption as objects of sexual pleasure (pornification). But, I think, it is precisely their hyperaware mimicking of girly pinup pics and “nudes” that results in failure, here understood as a critical disruption (the glitch): that is, failure not as a deficiency, but failure as a rupture of the categorical containment of idol-making golden frames and Instagram filters.

The glitching of frames and filters allows for something beyond the idealized and highly codified container of the body. The glitch, writes Russell, “aims to make abstract again that which has been forced into an uncomfortable and ill-defined material: the body.”18 The glitch is a way for the female artist to image her body in a way that troubles the body. The glitch is a way to free the body and its desires from a society insistent on pornifying any body labeled female. The gum sculptures Wilke attached to her skin in S.O.S. are glitches, as is her body hair, indicating Wilke’s failure at displaying a feminine perfection of to-be-looked-at-ness. The warp and the weft of Riley’s textile are also glitches, as are the woven tattoos that cover her body, seen in Nudes 41 and the hunted (2022; fig. 3). In the hunted, Riley’s tattoos cover almost every inch of her exposed skin, but it is the figure of Artemis tattooed on Riley’s back and reflected in the mirror that catches my attention. (Might a catch also be a glitch?) Artemis, Greek goddess of the hunt and chastity, punished those who looked at her naked body without her permission, that is, those who tried to take her image from her for their own use. Artemis in the tattoo, with her burlesque performer curves and pinup-girl hairstyle, not unlike Riley’s own (note the way a tendril of Riley’s black hair snakes across Artemis’s bangs), looks at us looking at her. Are we then the hunted, as noted in the title of the work, who will be punished for our scopic transgression, mauled by dogs like Actaeon was? Or is her gaze an invitation to join her and Riley on the other side of the looking glass / glass for looking?

When Alice, at the beginning of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, says to her kitten: “Let’s pretend the glass has got all soft like gauze, so that we can get through,” she suggests that there is another space behind it. And “indeed, the glass did melt away, just like a bright silvery mist,” or, in our contemporary world, a glowing screen that tempts us late into the night.19 We lose ourselves in the looking glass / glass for looking, but, oh, this glass for looking offers so many other pathways by which to imagine ourselves. In the hunted, we see Riley on both sides of the looking glass; a double-sided Erin Riley (Erin/“Erin”). Erin AFK, decorated with songbirds and a bow, and “Erin” online reflected in a looking glass and holding up a glass for looking, her (hunted?) image woven as a “soft like gauze” picture on a cell-phone screen.

Irigaray writes of the double-sided Alice (Alice/“Alice”) in her 1973 essay “The Looking Glass, from the Other Side,” which operates as the preface to her book, Ce sexe qui n’en est pas un, published in 1977. Although not translated into English until 1985, Irigaray’s essay is almost contemporaneous to Wilke’s S.O.S. series and reflects a particular moment of feminist thinking and rethinking around women’s desires and the inability to express said desires through classical language (which is why Irigaray claims mimicry may be women’s only option to speak within patriarchy). Irigaray proposes something on the “other side,” something beyond the nom-du-père (name-of-the-father), that operates as a “woman’s language.” In theorizing a woman’s language, Irigaray offers something “plural, autoerotic, diffuse, and undefinable within the familiar rules of (masculine) logic.”20 This is akin to Doane’s theorizing of a “new syntax” that speaks “the female body differently.” Similarly, I think, the performative self-imaging employed by Wilke and Riley offers a “new syntax” of the female body based on the pose as strategic disruption: “plural, autoerotic, diffuse.” In doing so, the artists function as Alician subjects, writable as Hannah/“Hannah” and Erin/“Erin,” who actively posed in front of the camera (a 35-millimeter single-lens reflex [SLR] and a cell phone) in order to step through to the other side of the screen/mirror and image (speak for) themselves.

What does it mean to name Wilke and Riley as Alician subjects, which is to say a “girl online,” an “AI Alice,” as Walsh theorizes?21 A girl online is many things, but, above all, a girl online appears. And an artist girl online makes images of herself so that she may appear as an object with an objective, that is, as a subject: “The subject poses as an object in order to be a subject.” And yet, the artist girl online is not just a girl or a subject; she is “plural” and “diffuse.” She is Hannah and “Hannah,” Erin and “Erin,” real and not real. “Online,” Walsh writes, “a girl can hammer herself thin as gold leaf until she occupies the whole dimensions of cyberspace.”22 In this thinness, which is essentially the screen and its opposite sides (AFK/online), the technological body diffuses in boundless futurition. There are endless “Hannah”s and “Erin”s that exist online: “Existing online allows you to be multifaceted.”23 Riley points to this many-sided existence in regard to the photos (“send nudes”) that she uses as source material: “These are images that I’ve taken for someone, they’ve been sent, and they exist in ephemera on someone’s phone or email or whatever, and then I’m subsequently weaving them to make them real, like a marker of time.”24 Online, “Erin” is unraveled (“diffuse”), so AFK Erin weaves to turn the ephemeral permanent, a sort of reverse Penelope. In doing so, she looks at herself looking in order to make herself real, that is, to remember who she is AFK.

Alice (or is it “Alice”?) cannot remember who she is on the other side of the looking glass. But do I even know who I am on the other side of the glass for looking? Does the glass for looking produce historical amnesia? Can we resist the glass for looking as producer of art-historical amnesia? In my projective looking into a screen of poses, I want to remember not only who I am but also who is beside me and who came before me: the looking glass as temporal integrator. We are more than fifty years past the first publications of feminist art history, the first feminist art program, and the first curatorial interventions into the history of women artists.25 Putting Wilke’s and Riley’s work in conversation with one another, then, has another function: it closes the temporal gap between 1970s feminist art and contemporary feminist practices that interrogate the female body as a set site of meaning (the classical syntax of the body). Riley’s artistic labor is fully her own and fully reflective of the present moment. But it is also very much part of a lineage motivated by feminist politics and beliefs. This is the central claim of the recent exhibition 52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone, which revisited, re-created, re-presented, and re-envisioned Lucy Lippard’s formative 1971 exhibition, 26 Contemporary Women Artists. An additional twenty-six artists were included in the 2022 exhibition, all of whom were born in or after 1980 and live and work in New York City. While Lippard specifically wrote in the 1971 exhibition catalogue of the need to show work by women artists who “can rarely get anyone to visit their studios or take them as seriously as their male counterparts” due to “the prevailing discriminatory policies of most galleries and museums,” Amy Smith-Stewart, curator of the updated exhibition, elided any specific gendering by titling the show 52 Artists.26 (But might they be girl online artists?) This linguistic shift reflects a contemporary now that has untethered “feminist artist” from “woman artist,” which allows, as Smith-Stewart writes, for a “twenty-first century feminist expression that is inclusive, expansive, elastic, and free.”27

I like this term “elastic.” Elastic stretches, twists, and makes space, all of which is needed in the creation of a new syntax of the body, one in which the female body may be read as a queer body in its resistance to hetero- and cisnormativity. An elastic body is a strange body, a body estranged from logic, which nonetheless tempts us to consider the edges of our own desires and where/how they intersect with other’s desires. An elastic body is one that cannot be controlled; it snaps back at conformity. Hannah Levy’s nickel-plated steel and silicone sculpture Untitled (2020), included in 52 Artists, is, in its “quasi-kinky weirdness,” just such an elastic body (fig. 4).28 Stretchy, lumpy, flesh-colored silicone forms, which simultaneously evoke body parts and something vegetal (eggplant emoji, lol), are pierced by shiny, corseted metal ribs that terminate in sharpened fishhooks. The effect is attractive and repulsive, like an Eva Hesse box made of galvanized steel and rubber tubing, but also entirely uncanny, as if Levy dissociated the chandelier form from the purely domestic in order to make it unheimlich (strange).

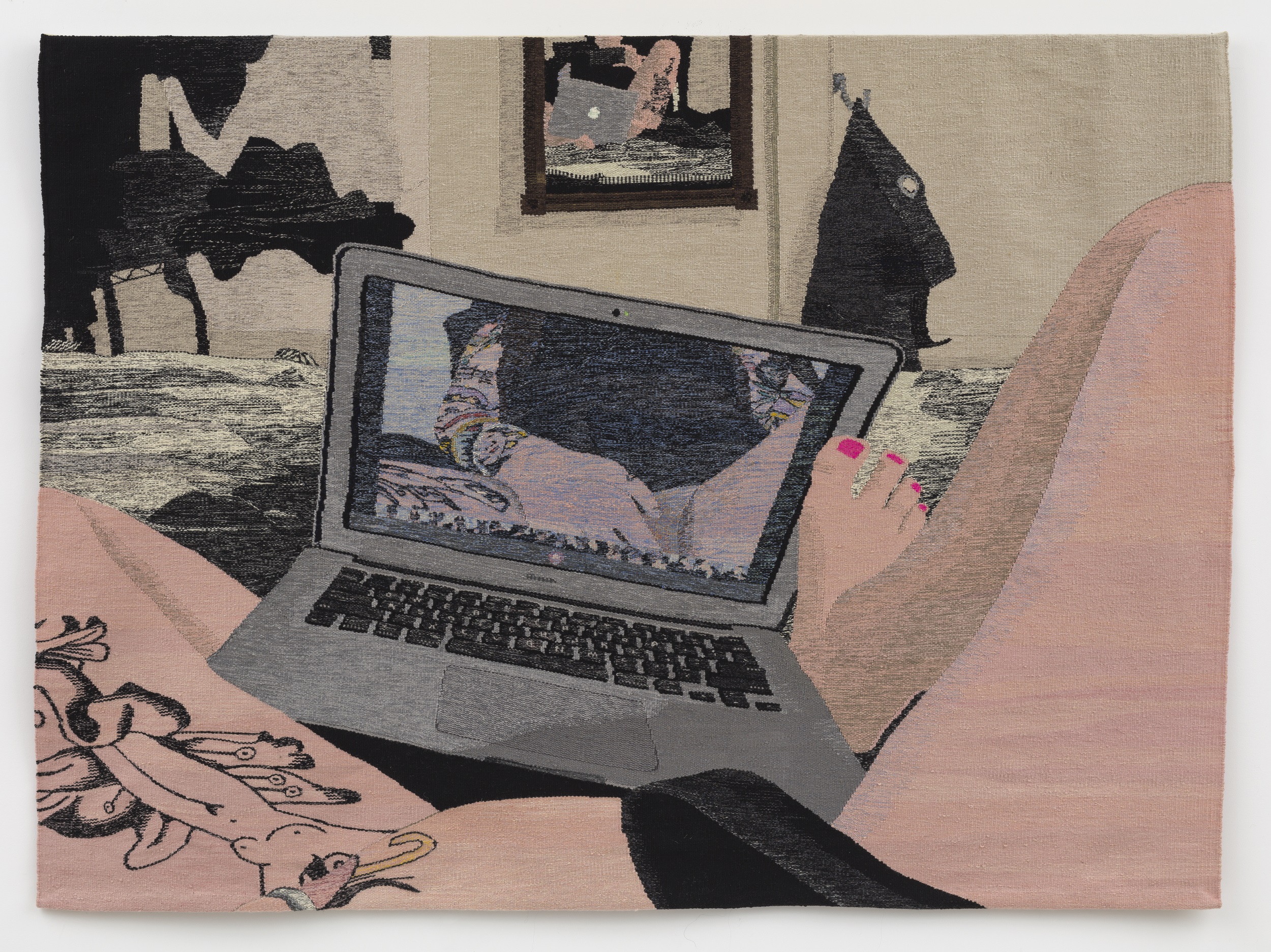

The undulating ribs of Levy’s sculpture structured my first encounter with Riley’s large-scale tapestry Webcam 2 (2020) in 52 Artists (fig. 5). The hard metal bent into soft curves fragmented and framed how I looked at the woven surface. The strangeness of Levy’s impaled silicone corrupted, like a not-unwelcome feminist virus, Riley’s triply imaged body. Small details caught my eye: a fuchsia-painted toenail pressed against the edge of a laptop, a metal hook on the back wall run through a piece of black fabric, the yellow crook of a forearm tattoo, and a cell-phone camera reflected in the mirror (fig. 6). Riley captured herself posing—in front of the laptop, the cell phone, and the mirror—and then wove herself into an image that is all about making oneself into an image. Riley’s pose, with legs spread to accommodate the laptop and maximize the view on the screen, is one of self-pleasure, both optic and haptic.

Webcam 2 is very much an image of masturbation. Riley posed with her left hand between her legs and her right hand holding up the cell-phone camera to capture the scene, converting the moving video on the laptop screen into a static photograph. Riley refers to the photos she takes of herself (“nudes”) as “mementos of loving, sexual, intimate relationships . . . these are the modern love letter.”29 But they are also images of self-pleasure and the pleasure that comes from self-imaging. In King Kong Theory, Virginie Despentes asks: “At what point do women connect with their own fantasies? How much do they really know about what really turns them on? And if you don’t know that, what do you know about yourself?”30 Riley taps into this interplay between sexual pleasure and self-awareness, rejecting the well-worn patriarchal split between body and mind, asking instead, how can one know oneself without looking at or touching oneself? Or writing about oneself? Or making art about oneself? These are the spaces of authorship historically denied to female artists who desire to image their own pleasure in ways that elide a pornified vision of their bodily experiences. Wilke, for example, approaches the abstractness of female pleasure (the thing beyond the visible) through her undulating latex sculptures, such as Homage to a Large Red Lipstick (1974–75), in which the overlapping layers of hyper-femme lipstick-red latex suggest the climactic waves of female orgasm.31 She most certainly took pleasure, too, in the posing and displaying of her own body, onto which she sometimes affixed small, vaginal chewing-gum sculptures, as we see in the number 40 S.O.S. photograph/ game card. Like the latex petals, the gum sculptures evoke the literalness of the corporeal and the abstractness of the emotional/psychological. The skin is a screen, a hammered thinness between interior and exterior. The gum sculptures evidence the vulnerable permeability of such thinness, as these eruptive stars and scars blemish Wilke’s culturally idealized (model) girl body. We may read these chewing-gum scars as visible exterior markers of the invisible interior wounds of societal objectification.32 They are the wounds that result from being used for another’s pleasure, from being measured against illusionistic ideals, from conforming to the rituals of beautification, from being subjected to patriarchal codes of gender and sexuality. They are the wounds so often repressed, or that we are told to repress, in the name of conformity and belonging. As Despentes writes:

We want to be decent, respectable women. If a fantasy seems disturbing, sordid, or degrading, we suppress it. Perfect little girls, virtuous housewives, and devoted mothers, roles constructed for the benefit of others, not to sound our own depths. We are programmed to avoid all contact with our wild side. First and foremost, be amenable, focus on the other person’s pleasure. If that means suppressing much of ourselves, too bad. Our sexuality is dangerous, to acknowledge it might lead to exploring it, and for a woman, all sexual exploration leads to being excluded from the group.33

The surveillance and forced suppression of women’s sexuality and desires continues to cause its own wounds. If, following Irigaray, women are unable to express their own desires through classical language, then, I think, what Wilke also makes visible in S.O.S. is the assertion that women’s suppressed desires will always find a way to return (recalling Sigmund Freud’s “return of the repressed”). Are these sugary scars scattered across Wilke’s body a form of “woman’s language,” which we have already noted as “plural, autoerotic, diffuse”? There is a particular eroticism embedded in the act of chewing sugary gum and transferring a moist wad from mouth to fingers to body. And her use of the pose to expose such eruptions of desire reveals exactly what is at stake (in question) when a female artist poses in production of her own image: her own pleasure.

The sweet scars on Wilke’s screen/skin are also glitches that gum up the machinic production of the ideal body, thus exposing it as a constructed social code. As Russell writes: “Glitches gesture towards the artifice of social and cultural systems, revealing the fissures in a reality we assume to be seamless. They reveal the fallibility of bodies as cultural and social signifiers.”34 This is why I read Wilke’s S.O.S. body as a glitched body: it has failed at seamless feminine perfection, which is precisely why it is successful as feminist strategy. So in thinking of the gum stars and scars as glitches, things both “horrifying and hilarious,” we may also think of them as something akin to Freudian slips, or what Freud termed Fehlleistungen and his editors retermed parapraxes.35 Fehlleistung roughly translates as a “mis-performance,” which suggests a failure in the system, Russell’s “indicator of something having gone wrong.” But wrong does not necessarily correlate to bad. Wrong is just a deviation from what is expected or mandated, like Wonderland or what is on the other side of the looking glass / glass for looking. Wrong is, therefore, rebellious in its desire for another space to speak from, using another language. (Glitch as “girl online language”?)

Alex Pieschel deftly points to what may be so appealing about the glitch as mis-performance when he writes: “Glitches indulge our fantasy of engaging with a system in a way that neither its rules nor rulers predicted. They reveal that the system was never pure in the first place and that pristine polish and usability are misplaced ambitions.”36 Pieschel’s thinking nicely carries over to our thinking on producing and consuming the image of the female artist as it relates to systems of self-representation. While it may be a “fantasy-fetish,” as the artist Shawné Michaelain Holloway names it, to think we have absolute control over how our images are used (consumed) involves a power that comes from authoring the image in the first place.37 Self-produced images (selfies) are a serious way for the female artist to position herself and her body in relation to the thinness of the screen: mimicry AFK, the glitch online.

So what is at stake when a female artist poses? One answer is everything. But perhaps a more satisfying answer at the end of this writing is found in the disruptive shift of making the private public, which one does by pos(t)ing (online). “Privacy was seldom good for women,” writes Walsh. “In its name, it has been (it is) the location of crimes committed against them. Private is often not ‘private for women’ but ‘women being private for others.’”38 The topics of Riley’s woven art—“menstruation, birth control, sexuality, masturbation, self-harm, domestic violence”—are the ones most often hidden under a veil of privacy, as if they are of no public concern, which tends to further subject female bodies to the abuses of patriarchal control.39 Refusing to remain private is a refusal to be silent. Yet, as Elissa Marder asks in her feminist analysis of the mythological story of Philomela: “In what language can one speak the effect of being silenced?”40 Philomela, whose tongue was cut out by the man who raped her to prevent her from speaking his name, used weaving to send a message to her sister (a coded material language between women who translate their rage into revenge). “The language of rage is a language without a tongue, a language of disarticulation,” writes Marder, in which one’s “experience is spoken perversely and becomes legible in part through the notas or ‘punctures’ in the fabric of its discourse.”41 One way to interpret notas is as marks on a body—gum stars and scars or tattoos—which operate as a language expressed without a tongue. The hypervisible notas on Wilke’s and Riley’s posed bodies suggest a feminist Fehlleistung, a strategic mis-performance, a “new syntax” to speak “the female body differently,” as theorized by Doane. The notas are also a glitch, an (artist) girl online language that refuses to be silent.

Notas: the hammered thinness between AFK and online . . .

A feminist glitch of the medium is the message . . .

Glitch it.

July 18, 2023: An image by Hannah Wilke was added and the figures renumbered.

Cite this article: Marissa Vigneault, “Pos(t)ing Online, or the Other Side of the Glass for Looking,” in “Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist,” In the Round, ed. Ellery E. Foutch, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17514.

Notes

Marissa Vigneault is a Book Reviews editor at Panorama.

- Joanna Walsh, Girl Online: A User Manual (London: Verso, 2022), 14–15. ↵

- The terms “female,” “woman,” and “girl” are used throughout this essay, each with particular meaning within the context of their usage and with awareness of their larger political definitions. ↵

- On deepfakes, see Moira Donegan, “Demand for Deepfake Pornography Is Exploding: We Aren’t Ready for This Assault on Consent,” Guardian, March 13, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/mar/13/deepfake-pornography-explosion. Walsh, Girl Online, 7. ↵

- “The pose as position.” Mary Ann Doane, “Woman’s Stake: Filming the Female Body,” October 17 (Summer 1981): 25. ↵

- An aside: both Wilke and Riley attended Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University in Philadelphia. Wilke earned a BFA and BSEd in 1962; Riley earned her MFA in 2009. ↵

- “When we put our bodies online, we are in direct dialogue with porn, both in the sense that we are being compared with porn which comprises 50% of the video content on the web and also in the sense that a similar process that we use to view porn, is now enacted on the non porn image—this is that we project onto the image our fantasy—in other words, turning a human into the object we would like them to be rather than understanding the being that they are.” Ann Hirsch, quoted in Grace Banks, “Ann Hirsch: ‘Overall, The Internet Has Become More Pornographic,’” Forbes, April 7, 2016), https://www.forbes.com/sites/gracebanks/2016/04/07/ann-hirsch-overall-the-internet-has-become-more-pornographic/?sh=7b3b8ce85db9. ↵

- “But porn is made using human flesh, using the bodies of actresses. And when it comes down to it, it poses only one moral problem: the aggressiveness with which porn stars are treated.” “It is men who dream up porn, direct it, watch it, and make a killing from it, and female desire is seen through the warped lens of the male gaze.” Virginie Despentes, King Kong Theory, trans. Frank Wynne (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), 89–90, 97, respectively. ↵

- Doane, “Woman’s Stake,” 30. Further, Virginie Despentes writes: “Men did not want to see their fantasy object step out of the cramped box in which they had placed her. . . . She had to disappear from public space. To protect the libido of men, who prefer the objects of their desire to know their place, by which they mean intangible, and, more especially, voiceless”; King Kong Theory, 91. ↵

- Doane, “Woman’s Stake,” 33–34. Doane also states, “The stake does not simply concern an isolated image of the body. The attempt to “lean” on the body in order to formulate the woman’s different relation to speech, to language, clarifies the fact that what is at stake is, rather, the syntax which constitutes the female body as a term” (33). ↵

- Craig Owens, “Posing,” in Difference: On Representation and Sexuality, exh. cat. (New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984), 17. Emphasis original. ↵

- Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London: Verso, 2020), 7. This publication is an expansion on Russell’s earlier essay “Digital Dualism and the Glitch Feminism Manifesto,” The Society Pages, December 10, 2012, https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/12/10/digital-dualism-and-the-glitch-feminism-manifesto. ↵

- Doane, “Woman’s Stake,” 33. ↵

- Throughout this essay, I use “nudes” and “send nudes” in specific reference to contemporary slang for acts of taking and sending naked pictures of oneself online or via texting. ↵

- Oxford Dictionaries named “selfie” word of the year in 2013. Silvia Killingsworth, “And the Word of the Year Is . . . ,” New Yorker, November 19, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/and-the-word-of-the-year-is. ↵

- Lisa Lazard and Rose Capdevila, “She’s so Vain? A Q Study of Selfies and the Curation of an Online Self,” New Media & Society 23, no. 6 (May 2020), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444820919335. ↵

- Owens, “Posing,” 15, 7, respectively. ↵

- On Irigaray and mimicry, see Hilary Robinson, Reading Art, Reading Irigaray: The Politics of Art by Women (London: I. B. Taurus, 2006), 29–32. ↵

- Russell, Glitch Feminism, 8. ↵

- Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (London: Macmillan and Co., 1872), 10. ↵

- Carolyn Burke, “Irigaray through the Looking Glass,” Feminist Studies 7, no. 2 (Summer 1981): 289. ↵

- Walsh, Girl Online, 15, 8, respectively. ↵

- Walsh, Girl Online, 12. ↵

- Walsh, Girl Online, 12. ↵

- Erin M. Riley, quoted in Lauren Hutson Hunter, “Three Shag Artists on Eroticism, Textiles and Contemporary Art,” Nashville Scene, November 5, 2020, https://www.nashvillescene.com/arts_culture/three-i-shag-i-artists-on-eroticism-textiles-and-contemporary-art/article_c19aab51-35c8-5611-a639-ca8ae7304fe7.html. ↵

- And yet, reading contemporary reviews of recent publications on women artists, one would think there are no precedents for such scholarship. Of note is Bidisha Mamata’s review of Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men (2022), in which she writes: “She {Hessel} brings to each artwork an attention that is both sober and pleasurable, a sensitive balance of probity, acceptance and fascination: exactly the kind of critical weight that female artists have been denied for centuries.” I fully support any scholarship that continues to draw attention to the institutional erasure and dismissal of women artists, and I appreciate Hessel’s use of social media (@thegreatwomenartists) to further expand knowledge of women’s artistic work. But, to state that “female artists have been denied” a “kind of critical weight” is its own form of erasure of the numerous scholars who have decisively and fundamentally changed the discourse of art history. Hessel’s contributions are not singular; her words are the result of historical feminist scholarship and her contemporary experiences, a temporal integration; Bidisha Mamata, “The Story of Art Without Men by Katy Hessel Review—Putting Women Back in the Picture,” Guardian, September 11, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/sep/11/the-story-of-art-without-men-by-katy-hessel-review-putting-women-back-in-the-picture. ↵

- Lucy R. Lippard, 26 Contemporary Women Artists (Ridgefield, CT: Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, 1971). ↵

- Amy Smith-Stewart, Lucy R. Lippard, and Alexandra Schwartz, 52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone (New York: Gregory R. Miller / Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2023). ↵

- Nina Willow, “Hannah Levy: Pendulous Picnic,” Brooklyn Rail, February 2020, https://brooklynrail.org/2020/02/artseen/Hannah-Levy-Pendulous-Picnic. ↵

- Amy Beecher, interview with Erin M. Riley, The Amy Beecher Show, podcast audio, September 19, 2022, https://amybeecher.show/Episode-59-Erin-M-Riley. ↵

- Despentes, King Kong Theory, 99. ↵

- A literal connection of the latex petals to female genitalia was solidified in the press release for Wilke’s first solo exhibition at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in 1972: “Included in the exhibition will be large wall sculptures made of latex and snaps, which are vaginal images.” “Hanna Wilke,” press release, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, September 1, 1972, https://feldmangallery.com/exhibition/003-hannah-wilke-september-12-october-13-1972#pressRelease. ↵

- I have elsewhere written on Wilke’s S.O.S. series in relation to the #MeToo movement. Marissa Vigneault, “Reading Hannah Wilke’s S.O.S. Scarification Object Series (1974–1982) in the Era of #MeToo,” in Iconic Works of Art by Feminists and Gender Activists: Mistress-Pieces, ed. Brenda Schahmann (New York: Routledge, 2021), 87–101. ↵

- Despentes, King Kong Theory, 99. ↵

- Russell, Glitch Feminism, 92. ↵

- Alex Pieschel, “Glitches: A Kind of History,” Arcade Review 3 (Summer 2014): 31. ↵

- Pieschel, “Glitches,” 40. ↵

- Gaby Cepeda, interview with Shawné Michaelain Holloway, Rhizome, September 24, 2015, https://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/sep/24/artist-profile-shawne-michaelain-holloway, cited in Russell, Glitch Feminism, 107. Russell notes that Holloway’s “fantasy-fetish” underscores “the implausibility of ever being able to fully dictate or refuse how one’s body can and cannot be digested through the digital platform.” ↵

- Walsh, Girl Online, 89. ↵

- Lizzy Zarrello, “This Tapestry Artist Is Moving the Needle on Female Sexuality,” Mission, March 11, 2022, https://missionmag.org/tapestry-artist-womens-month. ↵

- Elissa Marder, “Disarticulated Voices: Feminism and Philomela,” Hypatia 7, no. 2 (Spring 1992): 148. ↵

- Marder, “Disarticulated Voices,” 162. ↵

About the Author(s): Marissa Vigneault is Assistant Professor of Art History at Utah State University.