Woman As Image

PDF: Carr, Woman As Image

Alison J Carr, Woman As Image (Single Channel), 2009, https://vimeo.com/24132303

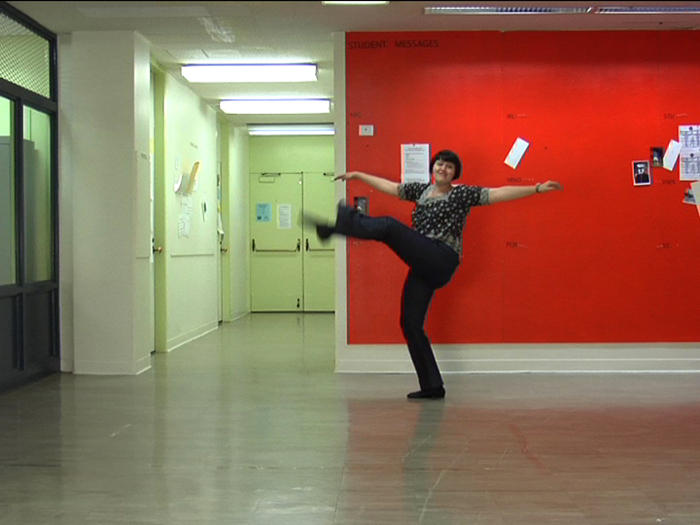

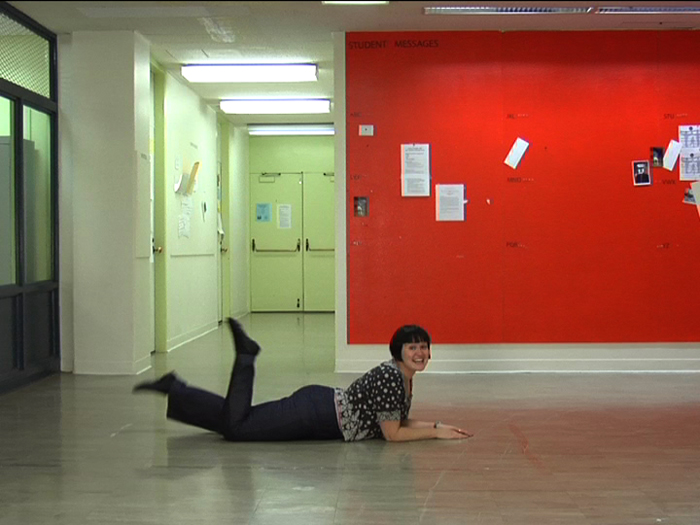

In Woman As Image (2009; figs. 1–2), I navigated the turbulent terrain of being the eponymous woman in the image. In the video, I sing and dance, amateur-style, editing multiple takes that demonstrate my increasing exhaustion. In truth, I was exhausted. Exhausted by the frequent recommendations I received while a Masters in Fine Art (MFA) student at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) that I should read Laura Mulvey’s germinal essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”1 I used my artwork to demonstrate my dutiful scholarship—it is Mulvey’s words to which I sing and dance in the video. At the same time, the video offers a contestation of Mulvey’s essay. Here, I would like to unpack the strategies of resistance I employ in the video and in my subsequent work.

I remember the impulse to sing and dance the Mulvey essay—an idea to which I was drawn by the end of my first year of graduate school. I was fearful of the idea, too. I knew it was an act of rebellion and refusal. But I was getting tired of Mulvey’s essay. And with each recommendation that I read it, I grew more tired of the implied and sometimes explicit critique that my re-creations of 1930s cigarette-card pinup girls would never function as I intended: that they would never convey ambiguity, complexity, or criticality; that they would never show subjects but always reduce women to objects. This was a difficult assessment with which to grapple. Its provocation was clear—I had to be more forceful in my critique of images of women or else risk reproducing the problems inherent in them.

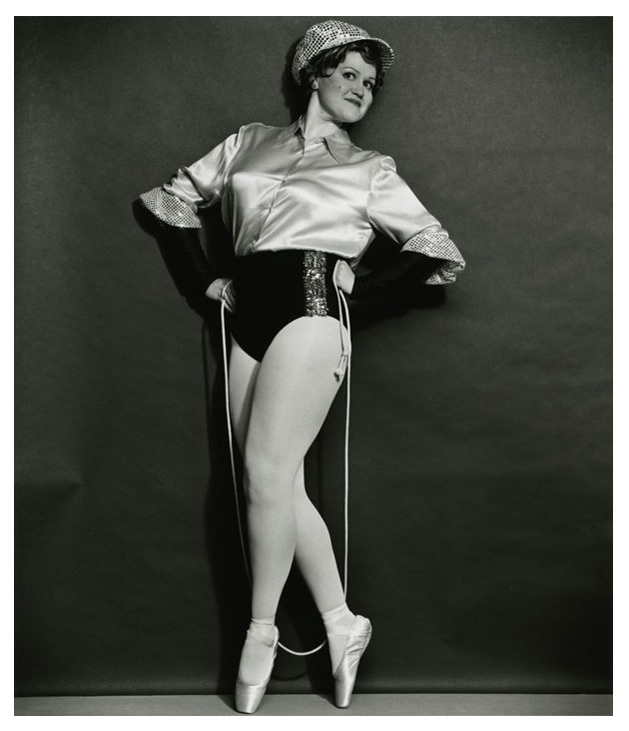

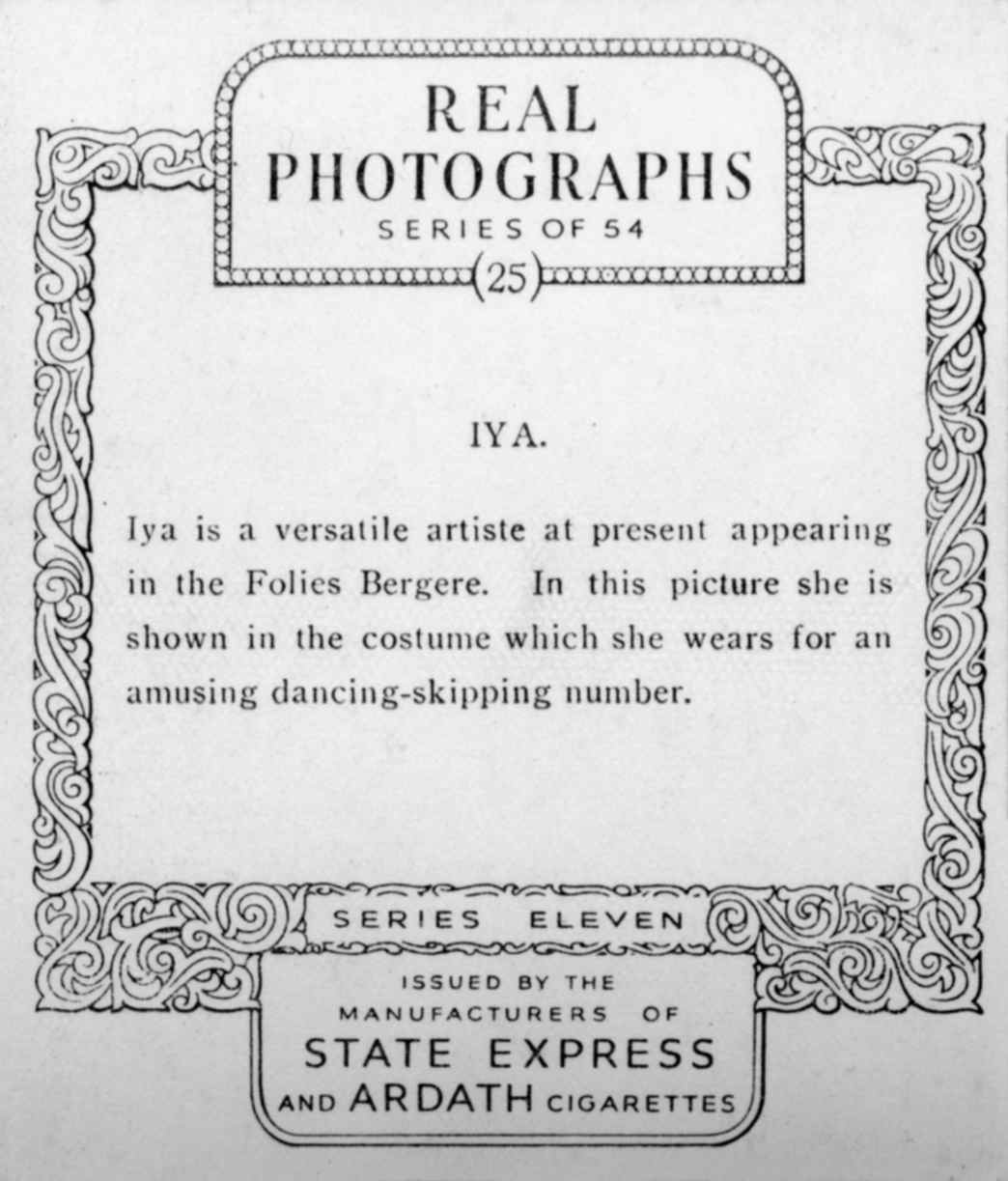

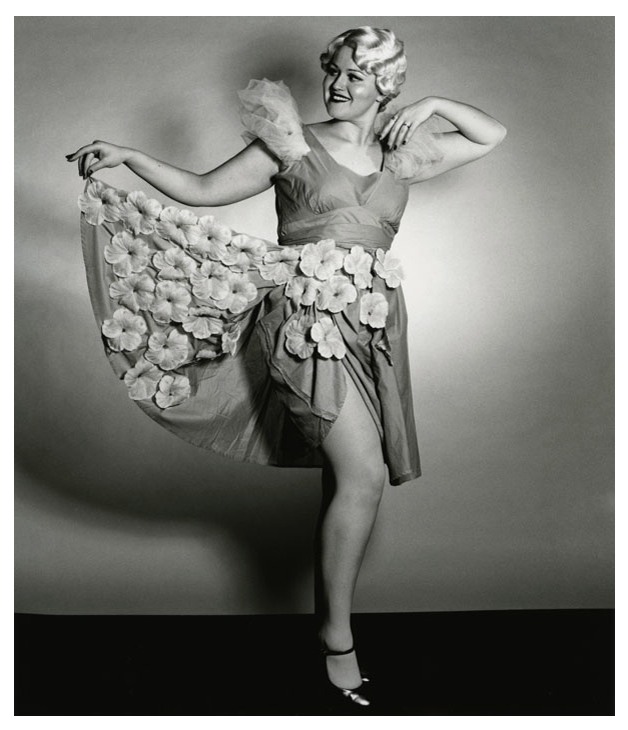

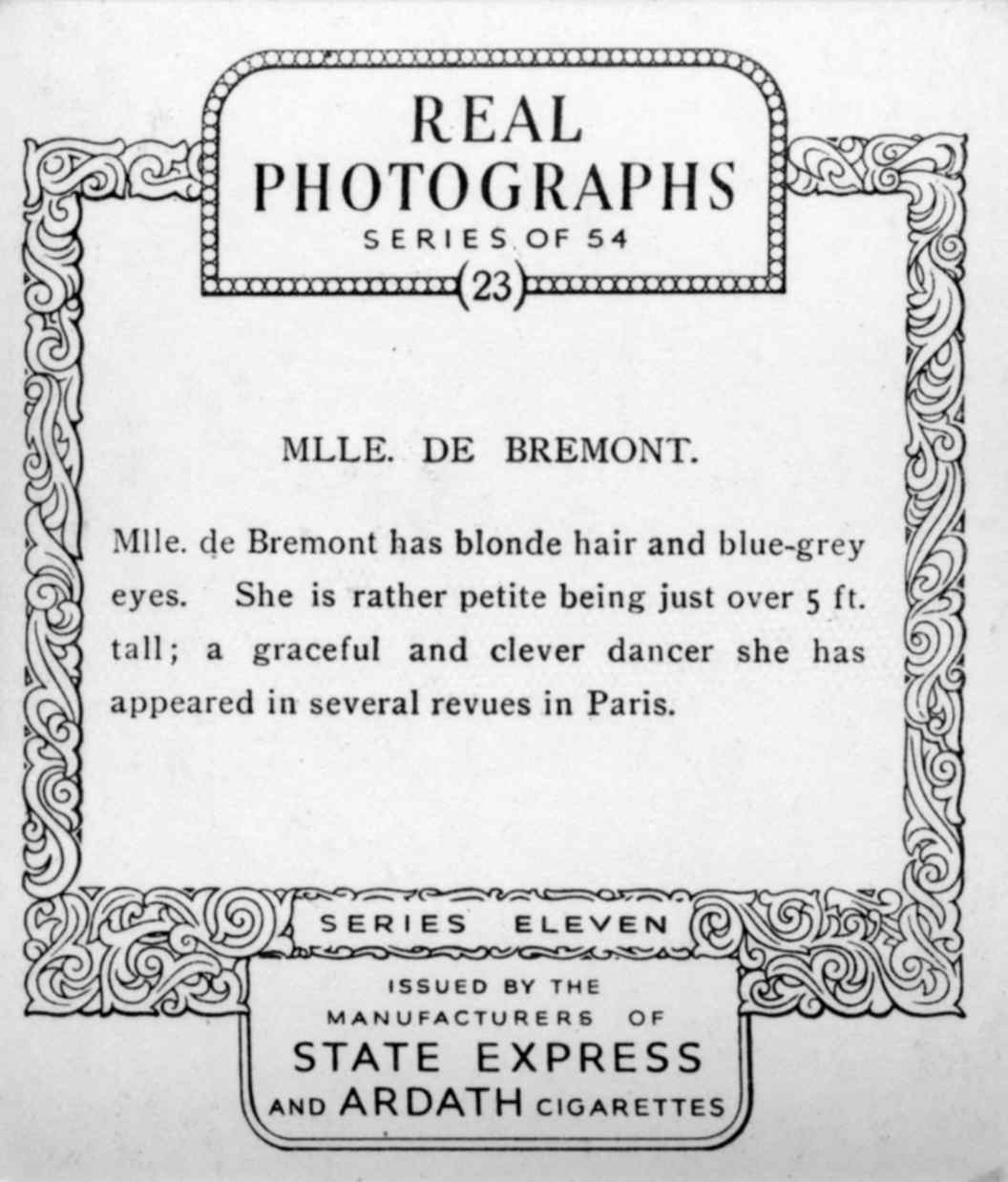

Let me introduce the cigarette-card work to which I have alluded. In 2005, at a rummage sale, I found a tin of cigarette cards from the 1930s. I was enchanted by the ones featuring female performers. I selected all the showgirls and bought them, and on the walk home, I decided that I was going to recreate all nine of them, becoming all the women in the photographs, as well as the photographer. At the time, this was a bold idea and one that would reform and redirect my practice. The project took three years to complete; I began before graduate school and kept working into my first year at CalArts. I shot and reshot the series Wish You Were Here, Real Photographs (2008; figs. 3–4) to get the lighting and mise-en-scène just right. My costumes were improvised and hot-glued. I hand-printed all the images in the darkroom, extensively burning and dodging and split-grading the photographs to bring more visual accuracy to the images. When I present the work, I always display photocopies of the backs of the original cigarette cards at their original size with their minibiographies of their subjects: it is important for me to honor the women as whom I masquerade. In this way, I try to reinstate each woman as much as I dislocate her. This is a concern in all my work: through the material decisions I make, I strive to register reverence and respect as I represent what is not there, the absence.

At CalArts, the project, on the whole, made those around me nervous. I was, after all, doing something deeply uncool—following my desire, my pleasure. Sharing the work, this project continues to find new audiences who see and enjoy the pleasure in my connection to this specific history. The project became a gateway for me; through it I have found the conceptual and critical issues that underpin all that I do. Indeed, I have developed some expertise in showgirl culture and history, which has led to important collaborations.2

Back to Mulvey. Her essay created a rupture. Written in 1973 and published in 1975, the essay applies Sigmund Freud’s theories of scopophilia and voyeurism to develop a framework for understanding how classic Hollywood films presumed or constructed a male viewer. Introducing the term “male gaze,” the essay demonstrates how film treats the sexual difference of female characters: they are given moments in which they become images to be looked at by men. Specifically, women characters are established by three men: the director of the film, the male protagonist, and the male spectator of the film. In Mulvey’s analysis, the woman character is a cipher, a zero-point, a locus for others. She is an image, and therefore she is nothing.

I adapted a key section of Mulvey’s essay into the song I sing, a cappella, in Woman As Image. My lyrics are sung to the tune of John Kander and Fred Ebb’s “And All That Jazz” from the 1975 musical Chicago:

1.

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance,

pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.

The determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly.

In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at

and

displayed,

2.

with their appearance coded for strong visual impact

so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.

Woman displayed as sexual object is leitmotif of erotic spectacle: from pin ups to strip-tease,

from Ziegfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to

and signifies

male desire.

3.

Mainstream film neatly combined spectacle and narrative.

(Note: however, how in the musical song-and-dance numbers interrupt the flow

of the diegesis.) The presence of woman is an indispensable element of spectacle in normal narrative film,

yet her visual presence tends to work against the development of a

story-

line.3

My song’s lyrics, though not taken entirely verbatim from Mulvey’s essay, identify the sharp points of her argument. The uneven gender dynamics presented in classic Hollywood films expand beyond film to all forms of erotic spectacle. Women are outside the forward momentum of the narrative. Their voices only exist within the song and dance numbers. This mirrors the way that women’s voices did not have a place within structures of power at that time. The clarity and force of this point of view is seductive. And yet, I argue Mulvey’s essay must be seen within a specific context, namely that of the enveloping, immersive space of cinema.4 How we consume images now, with our diffuse and fragmented attention spans and pocket technologies, is vastly different.

I have always been interested in looking at images of women to see where subjectivity might be intervening in the image, in spite of the image’s strictures. I have been looking for the traces of the person, her realness, complicating the image.

In Woman As Image, I pair my routine with that of Gilda, played by Rita Hayworth, performing “Put the Blame on Mame” in the film Gilda (1946).5 In the film, she struts out into a floor show, abandoning her cape and singing. She is a female force of nature, whose shimmies can be blamed for natural disasters:

One night she started to shim and shake

That brought on the Frisco quake

So you can put the blame on Mame, boys

Gilda’s dancing, singing, and seductive glove peel all indicate Hayworth’s talent for, and experience of, performing. She generates a kind of physical charisma, sexiness, and knowingness that comes from her own years of honed expertise. The song’s implication is to blame sexy women, which appears to name Hayworth’s defiant antagonism to Mulvey’s three men. The assumption is always that to be the subject of the gaze is to not know.

The “Put the Blame on Mame” routine is a complicated moment in the film and in readings of the film. Echoing the three theoretical men in Mulvey’s essay, here we seem to have more than one woman, more than one meaning. There is Mame, the sexy woman onto whom all ills can be blamed; there is Gilda, the character who dances as a way to state who she is and liberate herself within the storyline (although shortly after she is shamed for doing so); and there is Hayworth, the actress whose astounding self-possession inhabits the image with assertive force.

My singing and dancing in Woman As Image does no such thing. After two years of reading theory at CalArts, I was disembodied. I was out of my body. Fitness and strength had left me, and I was not taking dance classes. My dancing in the video is unpolished, as though I am rehearsing or learning steps. In this way, it reaffirms Hayworth’s impeccable technique and physicality. Hayworth also has the Hollywood apparatus constructing her dance routine with artful camera angles, pans, edits, and cuts. I point to these Hollywood techniques for image construction by doing the opposite: my camera is static, on a tripod; the scene is set in a banal hallway. Bringing together the Gilda material and the footage of me, I let the viewer see the complexity—all three men, all three women, and all the other multiple film professionals implied in Hayworth’s number versus me, dancing in the art office at CalArts.

I reperform my number multiple times. It is as though the song, the words, and the essay are a trap from which I cannot escape. I perform and perform and perform, registering my engagement with the essay over and over and over. Do the words of the essay ward off the male gaze through their enunciation alone? My service and engagement with the essay keep the male gaze at bay. My repetitive, raw, imperfect delivery and informal everyday wear convey my subjectivity. The provisional art-office context is my stage. I am an art student, I say, and I have read Laura Mulvey’s essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” over and over and over again.

Let me reiterate. Hayworth is not an empty cipher. She never was, with her open-armed appeal, her flowing hair, and her shiny, taut sheath dress that reads as phallic, complete, impenetrable. As she sings, her hyperfemininity mocks her three male viewers. “You look at me, you want me, then you blame me for being desirable, well I know, and I dance and enchant, because I can and I am free,” she seems to say. The song’s lyrics suggest as much.

Generations jump between Hayworth (who could have been my grandmother), Mulvey (who is a few years older than my mother would have been), and me—a symbolic granddaughter, daughter, attempting generational, reparative work. We form a line through the twentieth century, echoing a kind of evolution of women’s visibility. I grapple with these differing contestations: from the subtextual resistance in Gilda’s singing and charismatic dancing, to the textual provocations of Mulvey, to my own gestures. My performance is both textual and also embodied. I both draw on Gilda’s song-and-dance resistance and bring this strategy to the 1970s and apply Fosse-style moves to the lyrics of my Mulvey song.

After my MFA, I began a practice-led doctoral program. I made the photograph Being & Becoming (2010; fig. 5), toward the end of my first year. It was a kind of statement of intent or manifesto—or perhaps even my methodology chapter. I composed the image by building up the piles of books I was reading onto the desk in my shared studio. I also composed my outfit, creating an ensemble that would not look out of place on the film set of 42nd Street, or Cabaret, or Chicago—the classic musicals set in the early to mid-twentieth century. (I am, at heart, a 1930s chorus girl after all.)

Like Woman As Image, Being & Becoming incorporates textual research. The books in the photograph served as my bibliography at the time. I am holding Judith Butler’s Undoing Gender (2004)—a heavy-handed signal to the viewer that yes, I am performing gender, and I am indeed aware that I am: an important point to make clear in my work and also, by extension, in the context of this In the Round.6 The art and visual culture histories we are collectively examining bear the imprints of the gender scripting of their time. Examining these histories is not to argue for an idea of innate gender but to unpack what we inherit. We are always in conversation with limitations that have gone before us. Women artists have always grappled with how they are seen and how their work is read.

Awareness is often seen as an important critical point—an artist must register her own awareness of how she is seen in the work in order to command the work. The tension, when discussing an artist’s work, is: do they know what they have done? Are they in on their own work? For Gilda and the gazes that hold her, the implication is that she is without knowledge. In the first theorization of the new burlesque scene, The Happy Stripper: Pleasures and Politics of the New Burlesque (2007), another book on my desk, Jacki Willson coins the term “awarishness.” Willson was writing on the way a performer might weave into her persona and presentation cognizance of her own sexual availability and engage in an extended flirtation with her audience.7

The books on my desk signify that I am paying my dues. This photograph is my proof. In both Being & Becoming and Woman As Image, I depict and complicate my engagement with theory. My body functions as a counterpoint to theory. It performs awarishness of my flirtation with theory and with my embodied display. Or perhaps, a reason to grapple with the theory—my body acts as a holding place for the desires that might remain, even after the theories on my desk have attempted to make sense of, tidy up, or neutralize images of women.

In Being & Becoming, I contrived and staged an image in such a way that I instituted my research methods in the image. The work says, “I read theory on gender, performance, and burlesque, and I responded by thinking—how can I embody my response? How can I take part?”

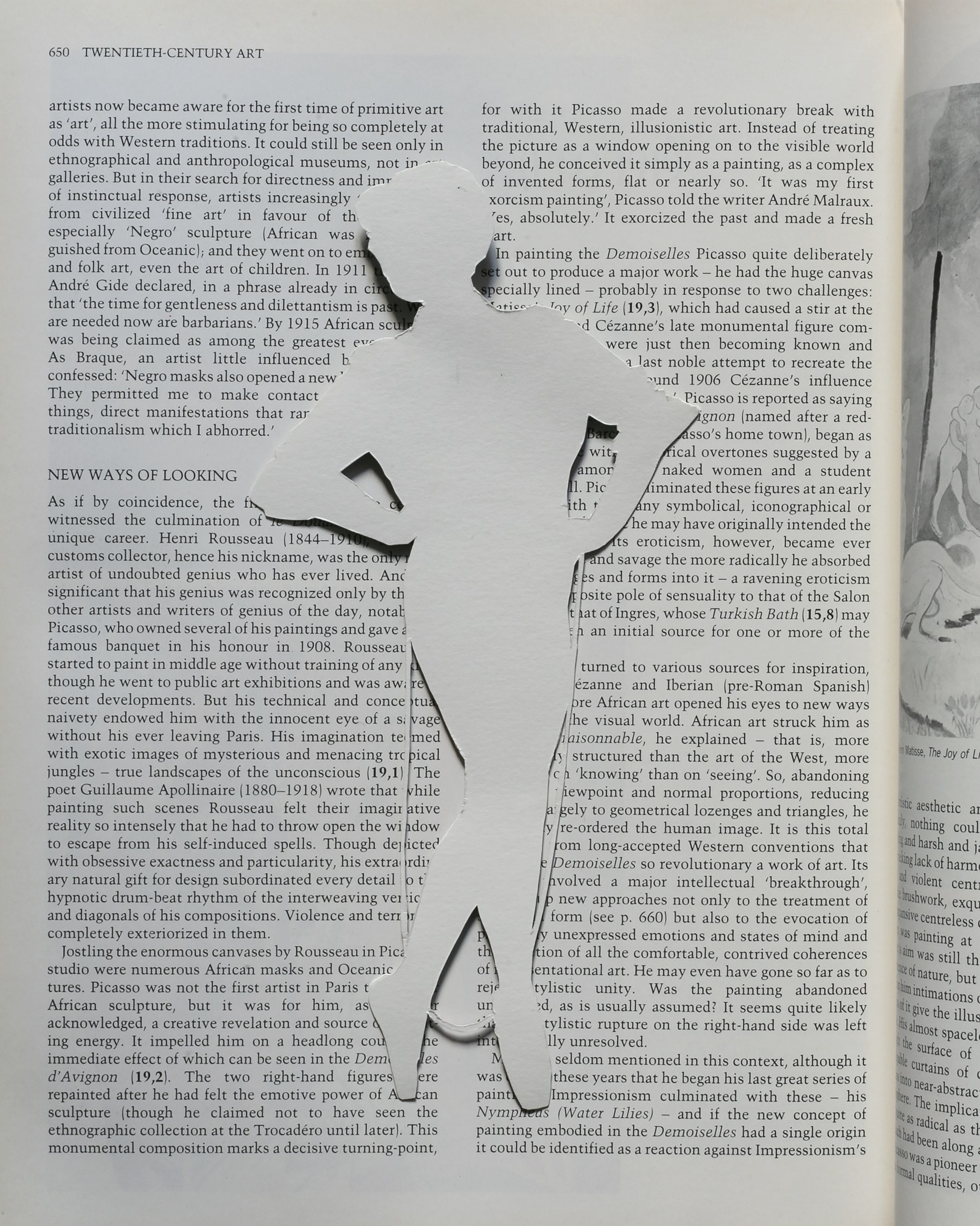

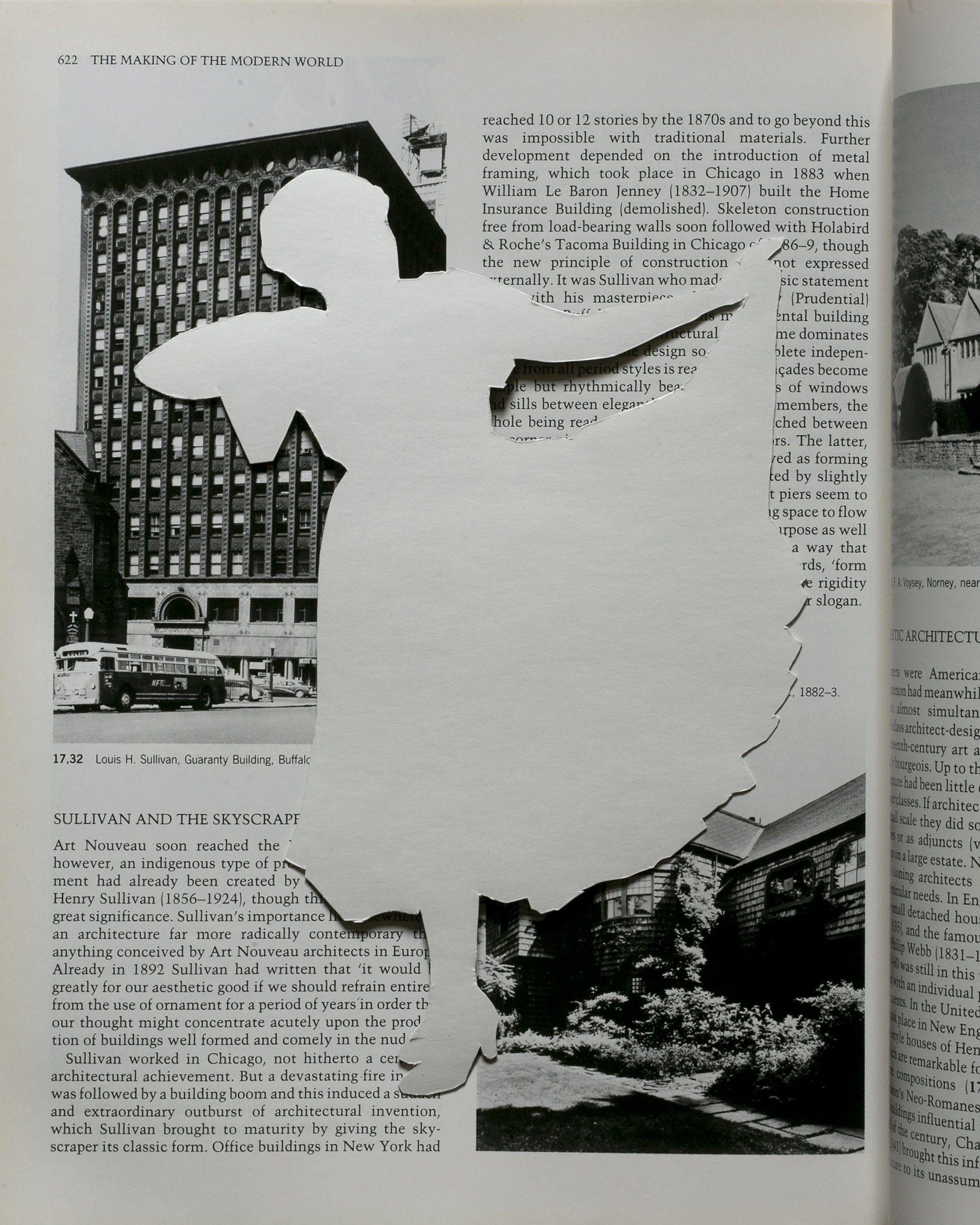

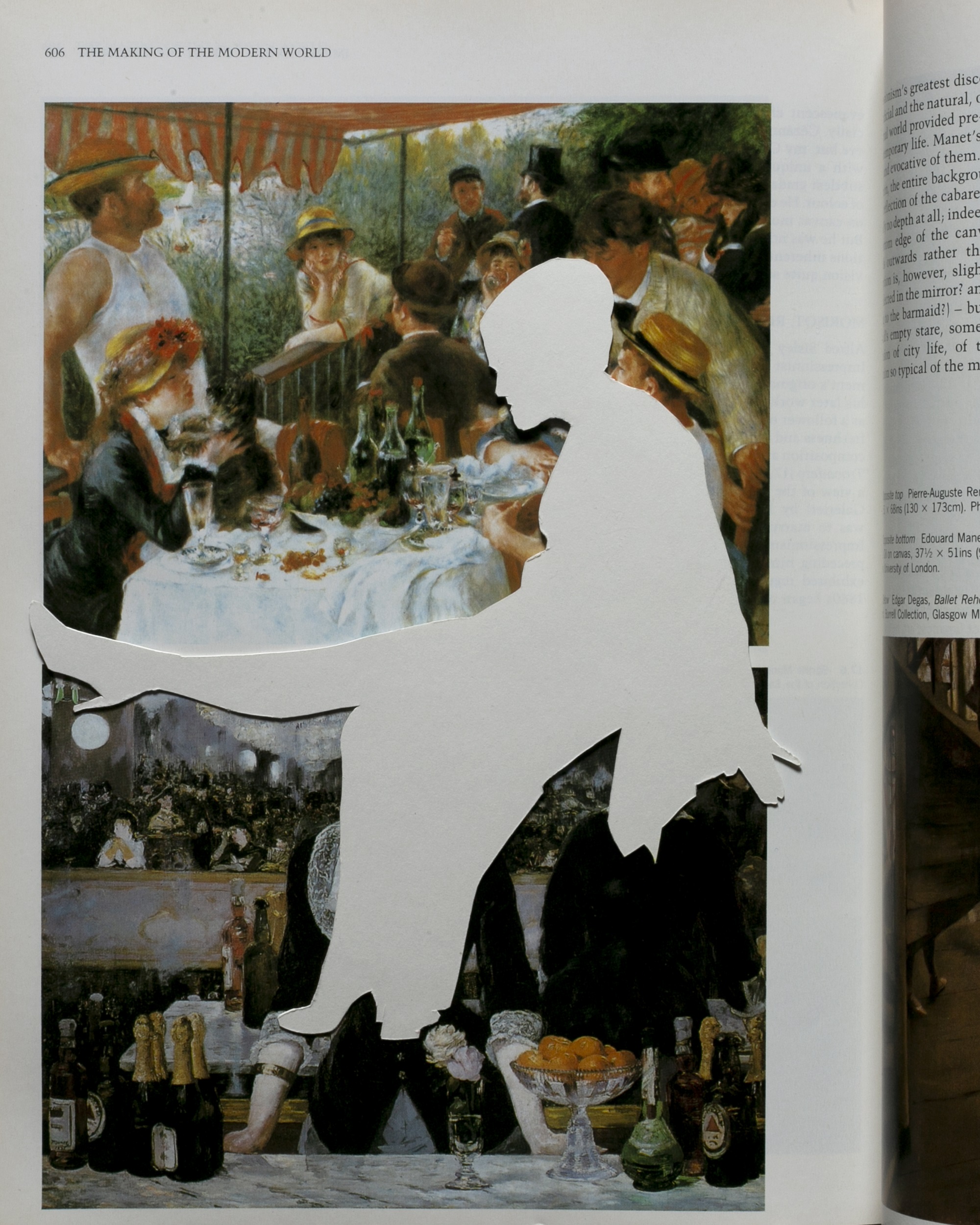

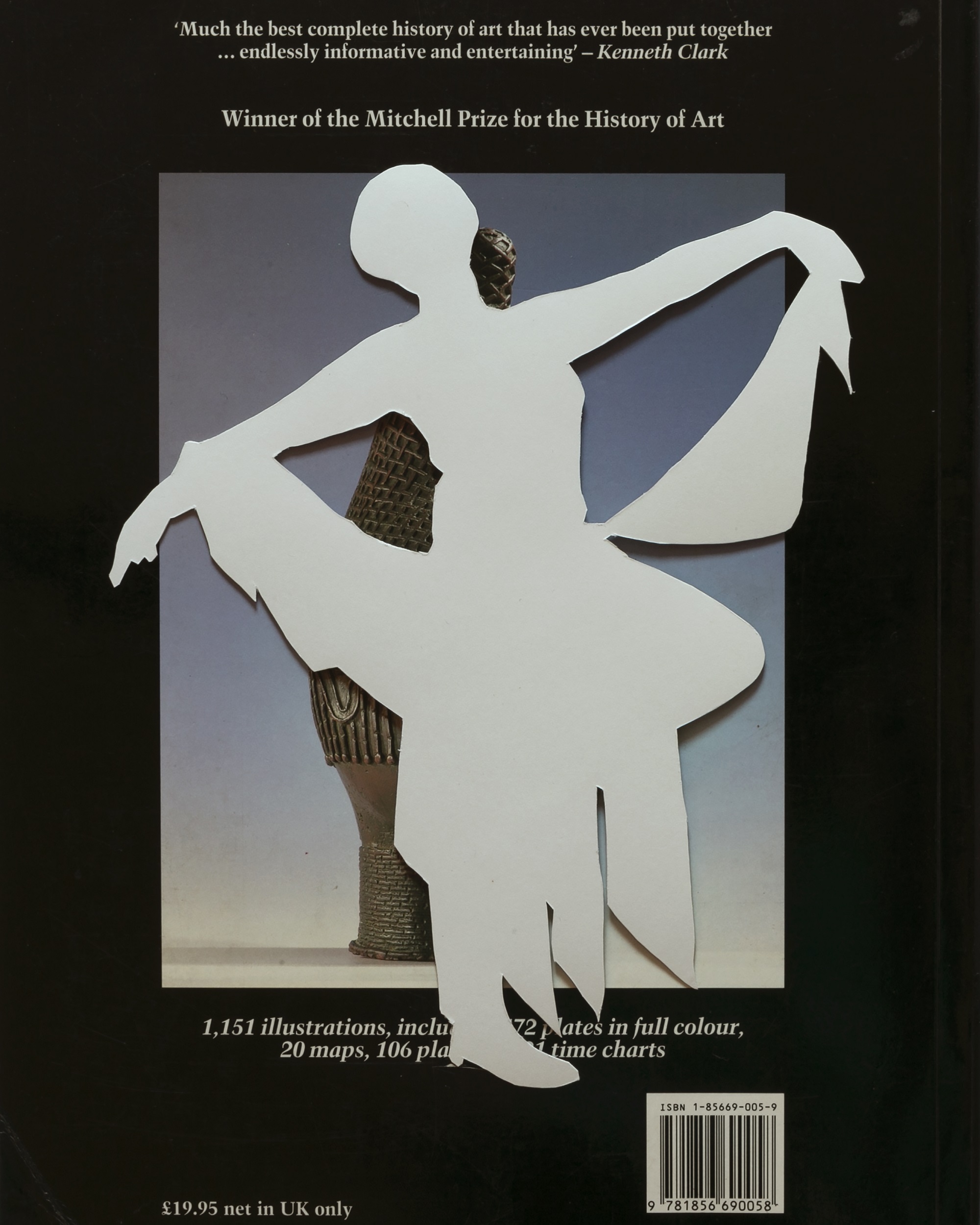

In Gaps in the Canon (2019; figs. 6–9), I recycle the cigarette card I discussed earlier. At times when I have had no budget to make work, I have innovated making new art out of old art. After all of my cameras were stolen from my uninsured studio, I began to cut out my photographs and create collages. In particular, I used my hand-printed rejected photographs, which I never throw out. I cut out the figure of myself and then recontextualize myself with playful and absurd material experiments, including gloss blobs, Bauhaus shapes, and paint distortions. Since I was using my own image, I was more playful than I ever am with found images. For this Gaps in the Canon series, I turned around my cut-out photographs and laid them face down in my book World History of Art.8 I had bought this book when I began my fulltime vocational art education when I was seventeen (a route recommended to me because of my lack of academic promise). I created a new image by photographing the pages and titling them according to the relevant running header with the chapter title and the woman in the photograph I was embodying. The white back of the photograph sits on top of the image, turning the absence into a positive presence rather than a cutout.9 My critique is obvious and clear: the limitations of the histories we inherit dovetail with the biases of the past. Art histories that reify the gold-framed figure also fail to acknowledge the photocopy, the resistance in the pose, the charisma of the subject that is hers alone.

There is, however, a risk, which is that I can never fully command how others read my images or, for that matter, the staged body of any woman. Where are bodies staged? In theaters. My final image, Manifesto (2018; fig. 10), is part of a portfolio of theater interiors that show that I will always step into the image, and with this gesture, I complicate the scene. This image is my reminder to myself to be defiant. I engage with theory, but I do not rescind certain pleasures. I do not turn in, hand back, or give up my exhibitionism. My performance of the self, my production techniques, and my consumption methods—the frisson of visual pleasure—is my method, and I am not going to stop investigating bodily display, feminine performance, or visual pleasure any time soon.

Cite this article: Alison J Carr, “Woman As Image,” in “Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist,” In the Round, ed. Ellery E. Foutch, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17301.

Notes

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in Visual and Other Pleasures, 2nd ed. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2009): 14–27. ↵

- Among these is, for example, my collaboration with Ellery Foutch for this essay; see also Alison J Carr, “The Stripper,” in The Routledge Companion to Media, Sex and Sexuality, edited by Clarissa Smith, Feona Attwood, Brian McNair (London: Routledge, 2017), pp. 362-370; Alison J Carr, “Felicity Means Happiness” (short film), Blackpool, Glasgow & Sheffield, 2018. ↵

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” 19. ↵

- Alison J Carr, Viewing Pleasure and Being A Showgirl: How Do I Look? (London: Routledge, 2018). ↵

- Gilda, directed by Charles Vidor (Columbia Pictures, 1946). ↵

- Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York: Routledge, 2004). ↵

- Jacki Willson, The Happy Stripper: Pleasures and Politics of the New Burlesque (London: I. B. Tauris, 2007). ↵

- John Fleming and Hugh Honour, A World History of Art, 3rd ed. (London: Laurence King, 1991). ↵

- This echoes what I note about Gilda: she is a positive presence, not an absence. ↵

About the Author(s): Alison J Carr is an artist. She works as a lecturer at the University of Huddersfield.