Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist

PDF: Foutch, Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist

Contributors

Emily Brady, “‘Shutterbug?’: Black Women Photographers and the Politics of Self-Representation”

Rachel Middleman, “Self-Portraits and Photocopies: Anita Steckel’s Feminist Collage”

Marissa Vigneault, “Pos(t)ing Online, or the Other Side of the Glass for Looking”

Alison J Carr, “Woman as Image”

Introduction

In 1944, Paramount Pictures featured a “Pin-Up Girl” as part of its Unusual Occupations film series.1 The short film begins not in an artist’s studio—at the site of artistic production—but rather at a site of the images’ consumption: in the drab interior of an army barracks. Accompanied by the spirited drums and horns of “I’m in the Army Now,” a young man reclines on the lower level of a bunk bed, reading a newspaper whose contents cause him to frown and furrow his brow.2 Setting aside the newspaper and laying it across his dark-olive woolen blanket, an uplifting thought seems to occur to him. He props himself up on his elbow and turns to look over his shoulder, good-naturedly shaking his head with a smile. The camera pans to follow the object of his gaze: a wooden board whose surface is covered with three rows of colorful cards, tacked up at jaunty angles. Each card features a lithe, scantily clad woman against a bright background. Despite differences in settings and costumes, each illustration emphasizes the model’s long legs, enhanced by high heels, as the women pose in a variety of environments and predicaments. “The pinup girl is at the [battle] front, too!” the narrator informs us. The camera proceeds to zoom in to inspect the small pictures, panning across the cards and the protruding nails that hold them in place, however temporarily. “Who is the artist, and who is the model?” the narrator asks, interrupting himself to note, “The boys don’t care, but we do!”

Fig. 1. Unusual Occupations, produced by Jerry Fairbanks (Paramount Pictures, 1944), ep. 3. Courtesy of Shields Pictures Inc.

The musical accompaniment transitions to a jazzy saxophone rendition of “You Are My Sunshine,” and the film dissolves from a close-up on a card of a dancer with a dramatic red background to a view of that very image in the process of its own construction. Delicate fingers alternately apply pigment and blend the surface of the now-familiar image; the body on the canvas is nearly fully realized, but her face is jarringly incomplete (fig. 1). Beside the easel, a woman’s hand is extended gracefully, displaying fingers with neatly polished nails. The camera once again pans out to unveil the artist at work, revealing and occasionally replicating the scene on the card: a blonde woman wearing a sequined hat and brassiere stands at an easel, simultaneously posing and creating. The narrator triumphantly announces, “Artist and model are one and the same!” This is how viewers were introduced to “Zoë Mozert, internationally famous for her American beauties.” Indeed, Mozert (1907–1993) was the ultimate 1940s “Calendar Girl,” famously serving as her own model for the pinups that she so prolifically sketched and published.3

Although the camera lingers on what the narrator terms the “prismatic wealth of the artist’s color box,” what we actually see is an array of pastels limited to tones of peach, pink, coral, gray, and white, a quick summation of the whiteness of this midcentury world of pinup culture and its emphasis on representing the skin and flesh of youthful and idealized white women. Periodically, Mozert cocks her head to the side and smiles; once the camera zooms out further, we see that she is observing her own reflection in a system of mirrors that display her form from all sides (in the round, as it were). At the push of a button, these suspended and motorized mirrors rotate around the artist’s easel, reflecting and refracting Mozert’s image in nearly infinite recession, suggesting a line of innumerable, identical chorus girls smiling as they lift their skirts and hold pastel crayons aloft. Carefully selected camera angles thus suggest the multiplication of the artist’s image in pictorial representation and mass-printed multiples, a mediated serialization of Mozert’s body in the act of creating her own image(s).4

The film quickly evokes the uneasy conflation of art, war, and sexual desire, cutting from the dark and drab army barracks to the dreamlike fantasy world of Mozert’s bright and airy Art Deco–inspired artist’s studio—or, at least, a movie set designed to appear as such. The film’s layers of presentation, representation, mediation, and multiplication reflect concerns that are inherent in the work of Mozert and the production and consumption of 1940s pinups, while it also reveals the fascination with which viewers perceived a woman who was both artist and model, director and actress, businesswoman and muse.

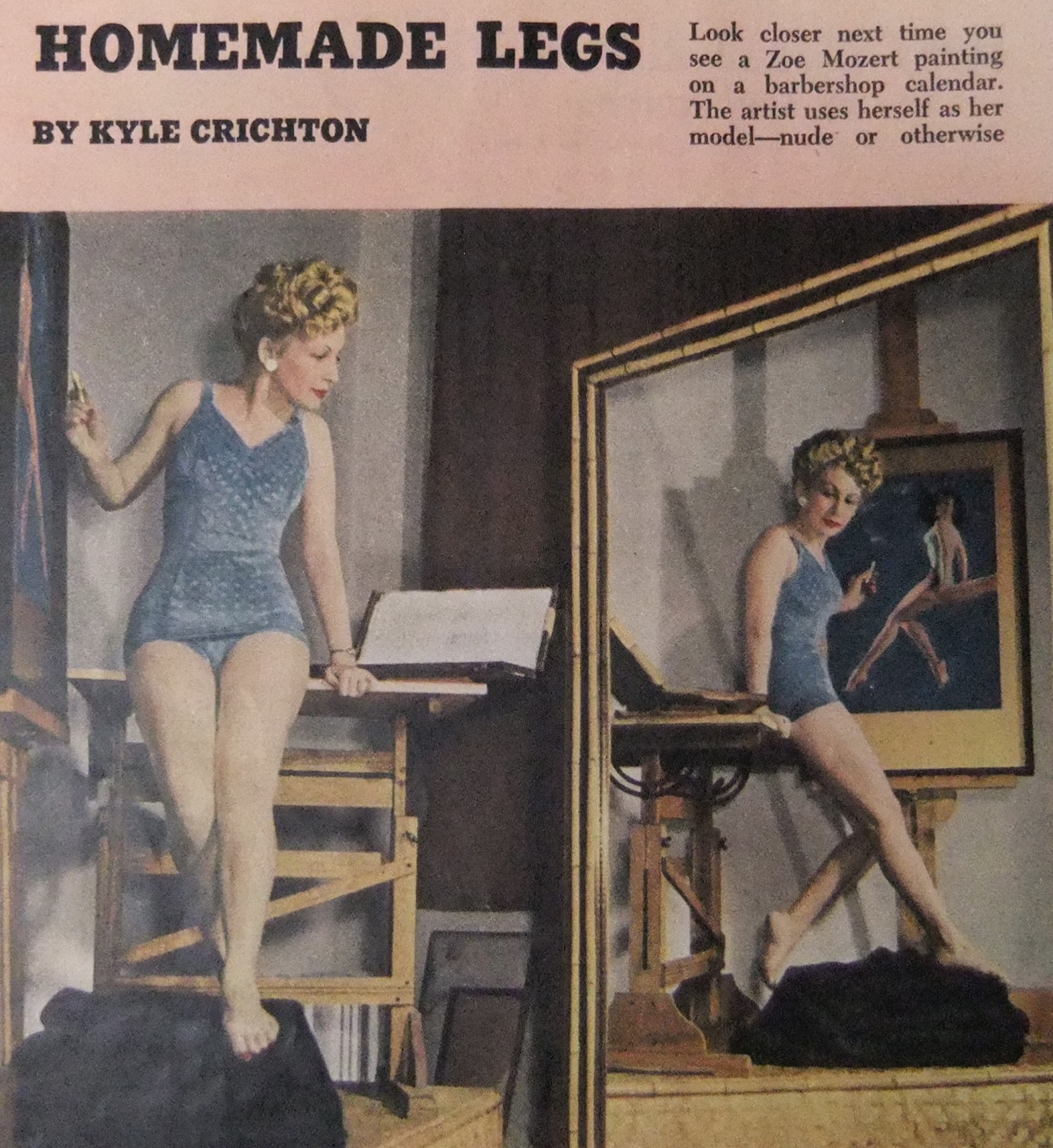

This In the Round focuses not only on the representation of women and women’s bodies in the art and visual culture of the United States, but rather especially on the representation of women as artists. Mozert frequently and famously emphasized the multivalent roles she played in her own artistic practice, as evident in the short film with which we opened but also in dozens of publicity photographs, including one reproduced in the pages of Collier’s Magazine under the somewhat bewildering headline “Homemade Legs” (fig. 2).5 Here, Mozert wears a swimsuit and full makeup, her blonde hair swept into an updo. Once again, strategic positioning of camera and mirrors allows the viewer to view her body from multiple angles—and to see her (ostensibly in-progress but already-framed) canvas, with its further echoes of her form. Mozert’s pinups were distributed nationally and internationally by the Saint Paul, Minnesota–based publisher Brown and Bigelow; small pictures (mutoscope cards) could be purchased from vending machines for a few cents. These were viewed not only in private settings and army barracks but also emblazoned with advertisements for local businesses and put on public display. As Collier’s attests, “Miss Mozert has turned out a great many works of art which are now to be seen in feed stores, barbershops and the new streamlined bowling alleys. . . . In most of these Mozert masterpieces will be seen the chassis of Zoë herself.”6

Thus, Mozert’s body became almost as famous as her art, fostering a fantasy of an artist-model who willingly and flirtatiously revealed herself to viewers while undergoing a complicated dance between the subjectivity of the artist and an objectified body that transformed into a “chassis” or other vehicle for viewers’ desires. Indeed, Mozert’s assertive engagement with commerce and publicity and her canny use of her own body helped to launch and sustain her creative career.

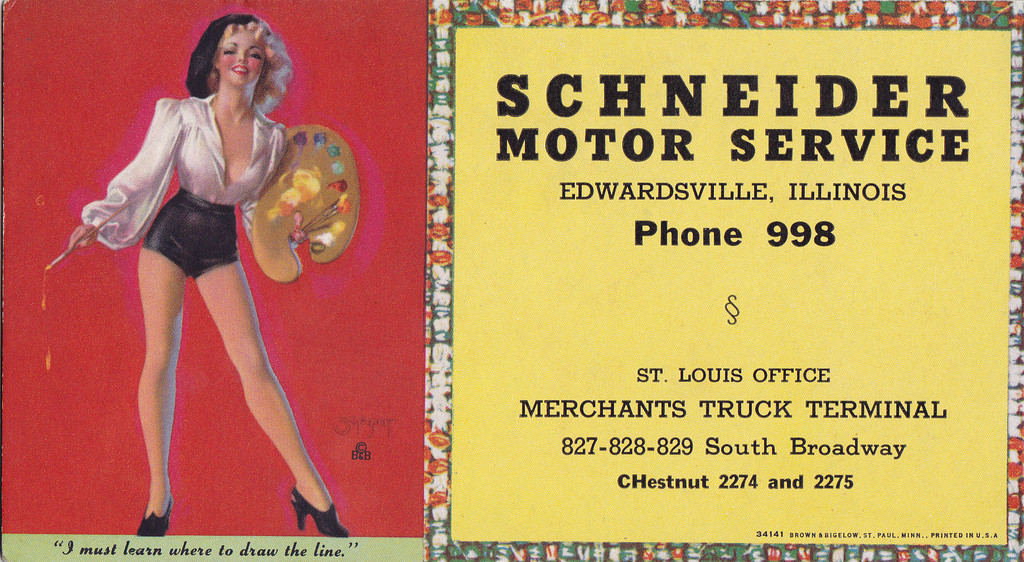

Beyond the production of publicity materials, Mozert also evoked the complexity of the flirtatiously posed artist-model in one of her illustrations (fig. 3a–b). In this image, both produced as a mutoscope card and reproduced alongside advertisements, Mozert’s costume is almost a parody of artistic representation—she wears a beret at a jaunty angle, along with a white blouse whose elaborate sleeves billow away from her form; in contrast, her short shorts and high heels expose nearly the full length of her legs, posed in an assertive V-shape and backlit. Light-blue highlights and shadows contrast with the saturated red background, accentuating the lines of her legs. As she leans forward, raising her chin to smile confidently at the viewer, she also grips a palette and cluster of paintbrushes; the extended paintbrush in her hand slowly drips thick drops of yellow paint toward the floor. Perhaps this seductive mess is what the caption refers to: “I Must Learn Where to Draw the Line,” evoking the need for self-regulation and restraint. In reality, as we have seen, Mozert created her works with oil pastels, a tactile medium that she often manipulated with her fingers and one that was frequently employed by popular illustrators. By representing herself instead with paintbrush and palette, Mozert aligned herself with the realm of the fine arts, suggesting some tension between the worlds of illustration and “high art.” Indeed, Mozert had enrolled in the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art in 1925; her transcripts indicate that she took classes in color and design, composition, and anatomy, advancing from her first-year “cast drawing” class to the “life class model” and a “costumed model class.”7 Her teachers included Elizabeth Shippen Green Elliott and Thornton Oakley, so we can think of her as an almost-descendant of Howard Pyle and the Brandywine School of illustration. She was a successful student, winning an Emma S. Crozier Prize for first-year Color and Design (1926) and later a Prize for Modeling (Mrs. John Harrison Prize, sculpture, in 1928), but she withdrew after two years, possibly due to financial difficulties.8 In subsequent years, Mozert became a commercial illustrator, producing magazine covers (often for pulp publications, such as True Confessions, or motion picture outlets, such as Screen Book), advertisements, and pinup illustrations.

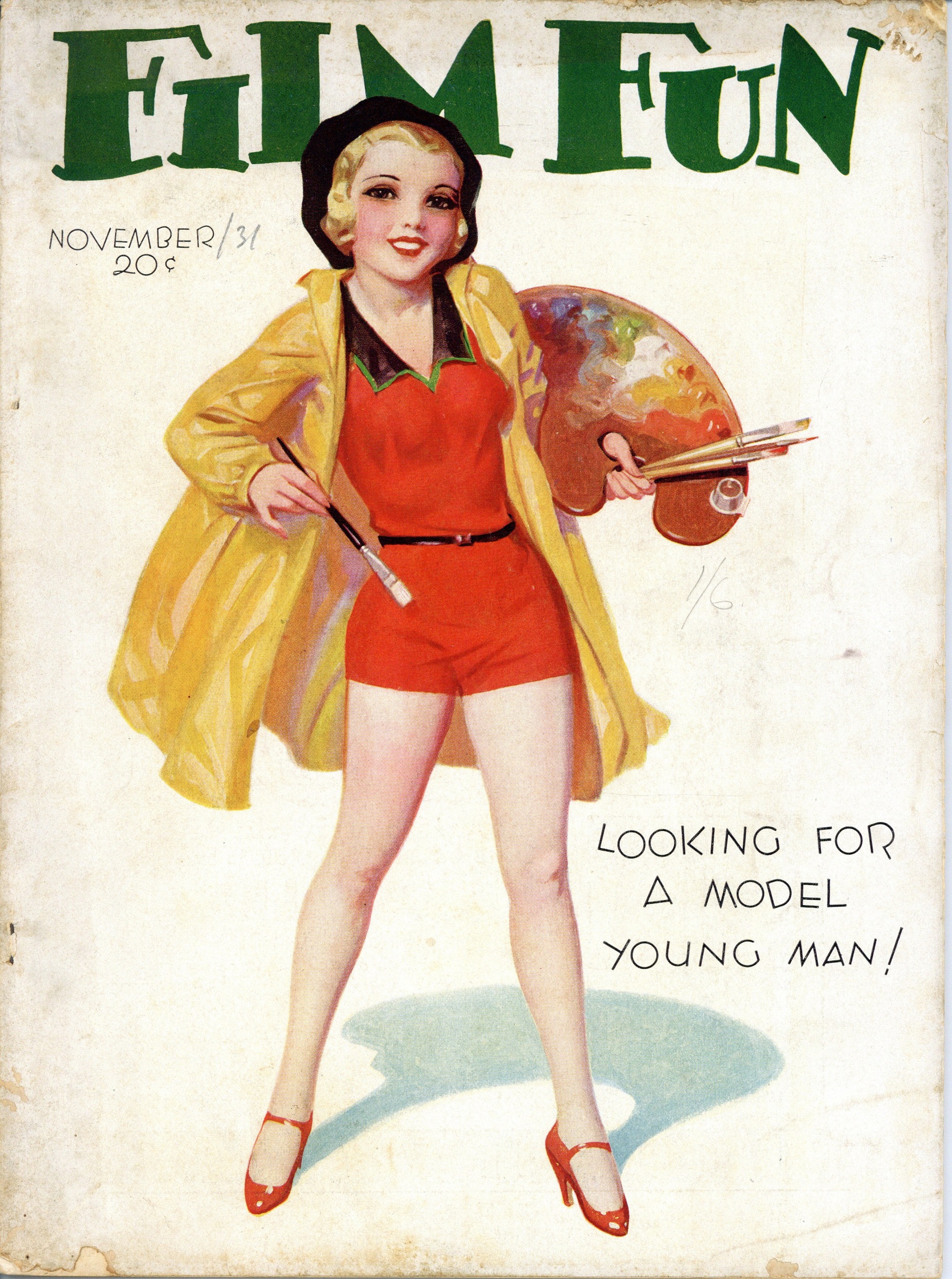

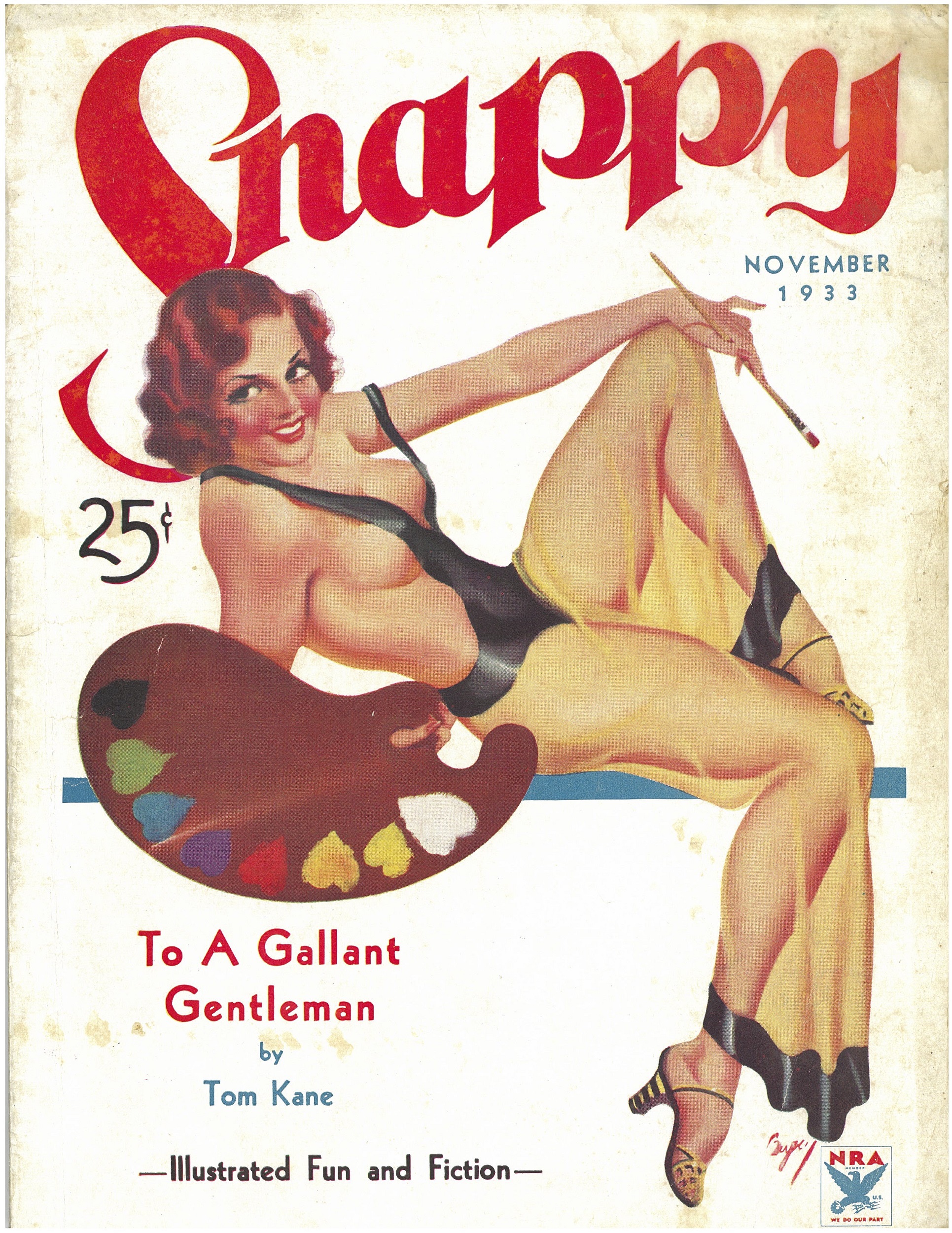

Yet Mozert was not unique in her depiction of a pinup shown in the act of painting. My research has revealed dozens and dozens of examples of what I refer to as “painting pinups,” scantily clad and posed with palette and easel in a variety of settings, from ateliers, seasides, and grassy meadows to empty fields of solid color, which were divorced from any specific locale (figs. 4–7). While pinup artists were undoubtedly skilled at sexualizing almost any scenario, this repeated motif of the seductive or flirtatious (imaginary) female painter—often depicted by male artists—offers us a window into attitudes about the art world, female creativity, and practices of looking and being seen.9

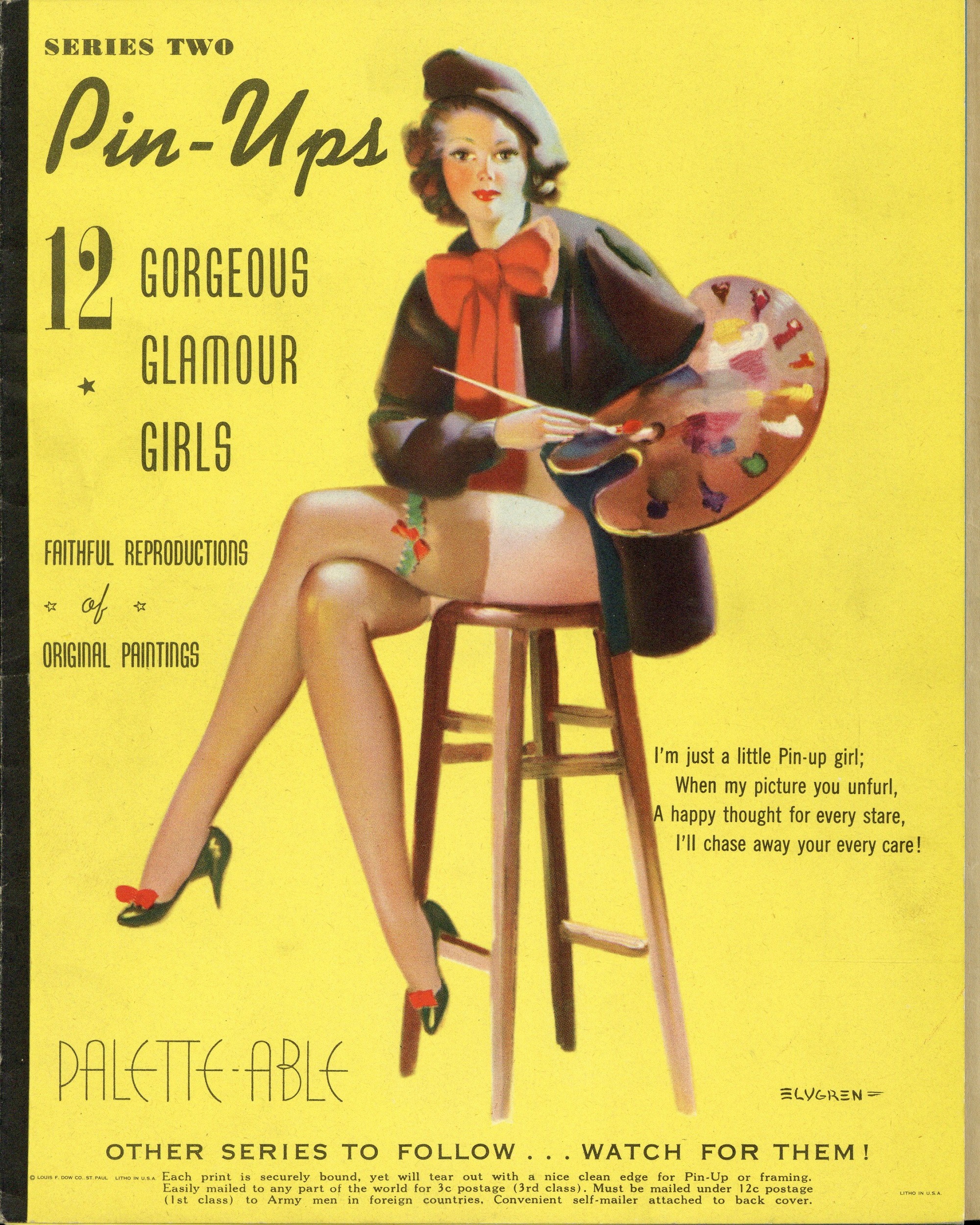

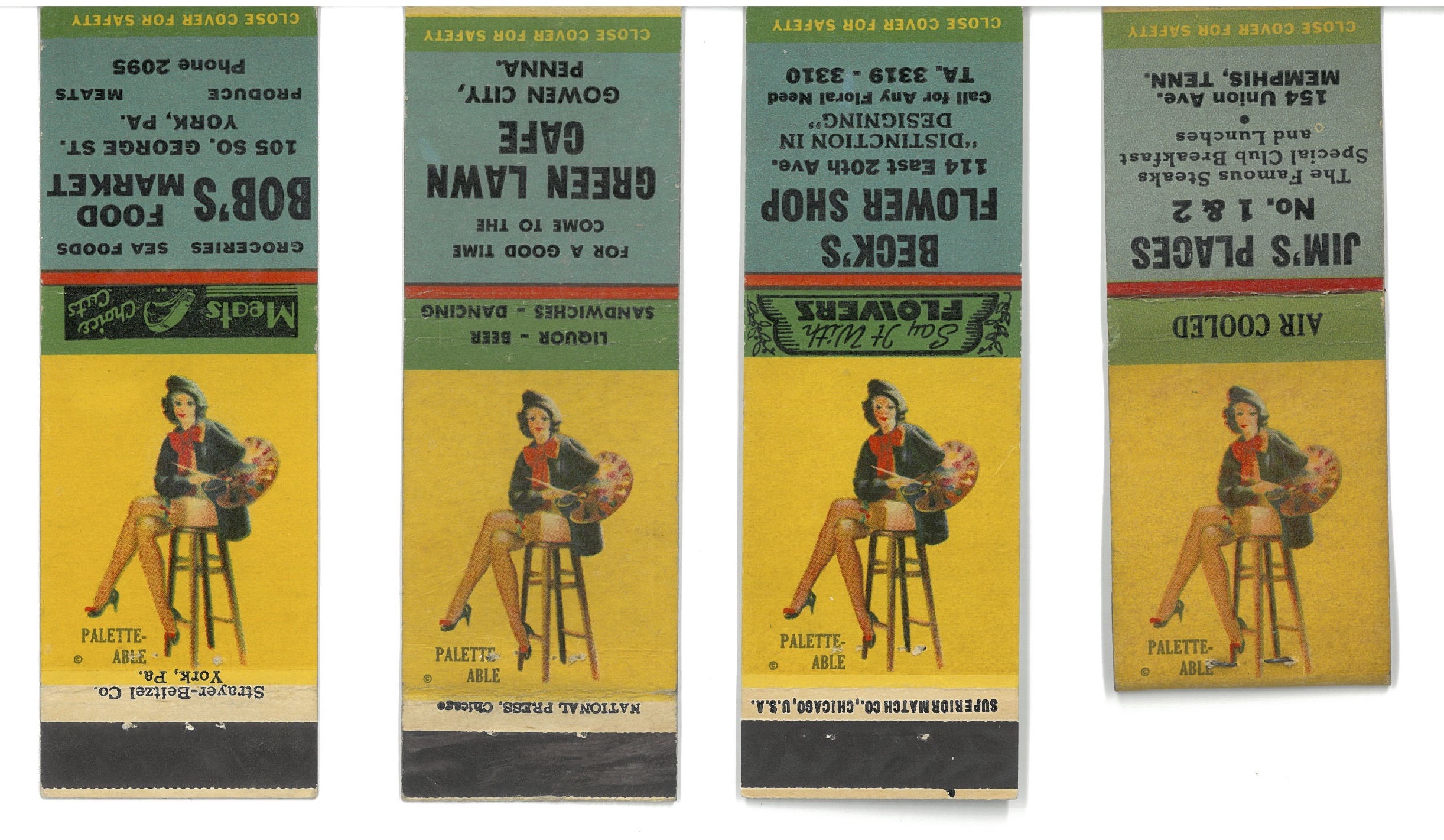

One of the most popular illustrations—reproduced in a variety of formats—seems to have been Gil Elvgren’s “Palette-Able,” published by Saint Paul, Minnesota–based Louis F. Dow around 1937 (fig. 6). Here, a demure brunette wearing a voluminous black smock is depicted perching on a stool, holding an enormous palette—and our gaze. Her stereotypical beret is painted akimbo, and she is shown hooking one of her high heels on a stretcher of the stool, crossing her legs to reveal stockings and a garter, whose red bow matches the one at her neck and the ones adorning her shoes. Although her paintbrush, loaded with red paint that matches the color of her lips and bows, is poised to make a mark, there is no easel in front of her. We can thus imagine that she is either perpetually frustrated, unable to put paint to canvas, or that the card we hold acts as the implied surface on which she is painting. Elvgren’s illustration was nationally distributed in a variety of formats, from a portfolio leaf (approximately 8 by 10 inches) to tiny matchbooks, whose scale and printing quality often leave the artist-model’s features misregistered and off-center (fig. 7). In an era in which few female artists were publicly visible or included in the art-historical canon, perhaps Elvgren’s rendering of such a figure did indeed make the idea of a woman who paints “palette-able”—“just a little Pin-up girl,” as the poem on one Louis Dow booklet proclaimed. Mozert’s self-presentation is a complicated engagement with this tradition. Does she subvert the trope or reinforce it?

When I first learned of Mozert’s work, I was full of questions. What did it mean for a woman to turn her own image into a pinup, to arrange herself into a seductive image? How did this fit with a feminist narrative of female artists? How did Mozert capitalize on her production processes for publicity? How might this imagery alter understandings of popular perceptions and tropes of artistic identity and practice? How could I understand Mozert’s agency and even complicity in the system of creating and dispersing idealized images of women? And how might this work fit into popular perceptions of artists and artistic creation?

At times, it has felt nearly impossible to pursue these lines of inquiry. In the era of the #MeToo movement and during the reign of a (former) US president who casually and gleefully bragged about his violation of women’s bodies, it was challenging to grapple with Mozert’s playfully confident displays. Studying the phenomenon of Calendar Girls felt even more impossible during the hearings for a US Supreme Court justice who indignantly defended his love of beer while denying the painful testimony of a survivor of sexual assault—and who submitted into evidence the pages of a mass-produced calendar annotated with his workouts and social activities.10 Yet this research has been sustained by collaborators and interlocutors who have encouraged and expanded the project and whose scholarship forms the basis for this In the Round.

Alison J Carr is an artist whose work productively engages with the popular culture of the early twentieth century, analyzing the self-aware producers, actors, dancers, and models in films, cigarette cards, photographs, and performances while also critically probing key scholarship in the field of feminist theory.11 Her work (some of which is featured in her contribution here) has helped me understand Mozert’s practice in a new light, opening my eyes to the ways in which artists could embrace questions of spectatorship, self-presentation, glamour, and play within the frameworks of critical inquiry and feminist practices. After meeting at the Terra Summer Residency in 2010, we have continued a productive collaboration and exchange; inspired by the work of Mozert, we formed the somewhat cheekily named Zoë Mozert Appreciation Society (ZMAS) to generate transdisciplinary research and explore questions of artistic practice, image consumption, bodily display, and relationships between artist and model, muse and producer.12 Balancing a playful spirit of inquiry with rigorous research and critical engagement, ZMAS searches for evidence of the lived experiences of pinup models and artists through archival hunting and imaginative acts of interpretation and speculation.

This In The Round grew out of a 2019 mini-residency, during which Carr and I co-crafted a call for papers for the then-upcoming College Art Association (CAA) annual conference. We invited contributors to explore the role of women artists in society and in art history, asking: How have female artists embraced, rejected, or adapted stereotypes of artistic identity and success to serve their own purposes? What is the role of gender in the production of gendered images? When the dominant genre of artistic achievement has been the representation of the female nude, how have artists inserted or adapted the representation of their own bodies? What does it mean to deploy one’s own body in image making? What does the exploitation through idealization of the artist’s body mean? How might we understand bodies as sites of and vehicles for exploration, experimentation, and even protest?

Although we had imagined these questions as ones that could be engaged across chronological and geographical spans, most submissions focused on the context of twentieth-century US art and visual culture. Four scholars—Susan Felleman, Emily Brady, Rachel Middleman, and Marissa Vigneault—joined us in presenting their research in Chicago in February 2020.13 Despite the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, their projects have continued to grow and develop, with many of the contributions reaching publication in other venues. This introduction offers both a sense of the original context of the session as well as an orientation to the essays that appear here: contributions by Brady, Middleman, Vigneault, and Carr.

Brady’s research on representations of Black women photographers balances an analysis of both fictitious images (advertisements or pictures of Black models merely posing with cameras) with self-portraits and images of professional photographers, including Florestine Collins, Eslanda Goode Robeson, and Elizabeth “Tex” Williams. The proliferation of these images, she argues, reveals both anxieties and fantasies about Black women as subjects and as image makers, depicted alternately as sexualized pinups and as competent professionals and agents of social change.

In the winter of 2020, Middleman presented work in progress on painter Joan Semmel’s early and recent works that trouble the categories of the “nude” and the “self-portrait.” Delving into the 1976 Mythologies and Me, a large three-panel painting in which one of Semmel’s own self-image nudes is flanked by a Playboy pinup and a faux Willem de Kooning Woman, Middleman articulated the ways in which Semmel cogently challenged the objectification of women’s bodies and deployed both camera and mirror as tools or “viewing devices” that assisted in the representation of her nude body from her own point of view. Now in her eighties, Semmel continues to represent her own nude body, extending and expanding this work while also protesting the invisibility of aging women.14 For this In the Round, Middleman turns to the collages of Anita Steckel, works that productively engage with the proliferation of women’s bodies in visual culture. Using a color photocopier, Steckel repeatedly reproduced, enlarged, and manipulated pictures (including images of herself nude), impishly both inserting herself into the art-historical canon and undermining its authority. Middleman analyzes these mischievous images and their bold subversion of traditionally binary oppositions: art and decoration, masculine and feminine, and original and copy. As Middleman reveals, Steckel’s playfulness is nonetheless hard at work in subverting the patriarchy of the art world.15

Vigneault investigates the possibilities offered by the “pose” and the “glitch” as strategies for feminist self-representation in this moment of ever-proliferating screens and images, building on scholar Joanna Walsh’s Girl Online: A User Manual. Vigneault’s February 2020 paper focused on Hannah Wilke’s body of work—her resistance to the commodification of the female body by focusing on her own pleasure, drawing on visual traditions from the art-historical canon (à la Steckel’s collages) to cigarette cards and twentieth-century pinups (à la Mozert and Carr).16 Here, she brings these works into conversation with contemporary artist Erin M. Riley’s tapestries and representations of a screen-saturated world, subverting “pornification” by means of her own self-imaging and visual strategies of authorship.

This In the Round also features an extensively illustrated essay by Carr in which she shares some of the works she created as part of her MFA thesis, during her practice-led PhD research, and beyond. These include the playful yet grueling song-and-dance endurance performance she generated in response to Laura Mulvey’s canonical “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” as well as feminist interpretations of vintage cigarette cards and pinup imagery, all buttressed by an extensive scholarly apparatus.

This collection of essays seeks to offer new perspectives on the representation and self-representation of women artists of the United States. Rather than aspiring to be all-encompassing or encyclopedic, we hope instead to create an opportunity for further discussions of women (and gender-nonconforming individuals) as creators, subjects, and mediators in American art. We welcome collaborators, contributors, and co-conspirators in this exploration and adventure.

Cite this article: Ellery E. Foutch, introduction to “Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist,” In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17193.

Notes

Foutch joined Panorama‘s Advisory Council in August 2022.

- Unusual Occupations, produced by Jerry Fairbanks (Paramount Pictures, 1944), ep. 3. I am grateful to Mark Punswick of Shields Pictures for sharing this film with me; for further information, see “Unusual Occupations,” Shields Pictures, Inc., accessed May 17, 2023, http://www.shieldspictures.com/unusualoccupatio.html. ↵

- Thanks to Bill Foutch for identifying the tune; Carson Robinson’s rendition of Frank Luther’s 1941 composition (Bluebird Records, B-11415-B) can be accessed via https://archive.org/details/78_im-in-the-army-now_carson-robison-frank-luther_gbia0086876b. ↵

- See, especially, Marianne Ohl Phillips, “Zoë Mozert: Pin-Up’s Leading Lady,” Tease 3 (1995): 30–38; Charles G. Martignette and Louis K. Meisel, The Great American Pin-Up (New York: Taschen, 2011). ↵

- The film continues for several minutes, lingering on many of Mozert’s canvases and giving a very abbreviated biographical sketch; the narrator eagerly anticipates the return of soldiers, reassuring women on the home front that the pinup girls are merely imaginary (and temporary) companions. ↵

- Kyle Crichton, “Homemade Legs,” Collier’s Magazine, April 1, 1944, 16, 64. ↵

- Crichton, “Homemade Legs,” 16, 64. ↵

- Alice Moser file, University of the Arts Archives, Philadelphia, courtesy of Jackie Manni, Office of the Registrar, University of the Arts, Philadelphia (personal communication, August 22, 2018). ↵

- The Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, List of Graduates and Prize Winners (Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, 1926), 4; The Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, List of Graduates, Awards and Prizes 1927–28 (Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, 1926), 6. Thanks to Sara MacDonald and Lillian Kinney, University Libraries, University of the Arts, for sharing more information about these prizes (personal communication, August 23, 2018). ↵

- This project grows from my deep admiration for the many feminist art historians who have analyzed the representation of women, broadly writ, in art and their investigations, as well, into the historical contexts of the art world and the artists’ studio. I am indebted to scholarship by historians and art historians, including Linda Nochlin, Griselda Pollock, Denise Murrell, Marie Lathers, Nancy Mowll Mathews, Tamar Garb, Hollis Clayson, Robin Mitchell, Rachel Middleman, and Sarah Burns; their work has illuminated pervasive attitudes about sexuality and labor relations within the artist’s studio, including documented and assumed relationships between artists and models, whose laboring bodies on display often implied prostitution. With thanks to artist Alison J Carr, I am also engaging with scholarship that seeks to complicate narratives of the male gaze or female objectification by recentering the agency of the female subject, building upon, yet departing from, Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema”—first published in Screen 16 (Autumn 1975): 6–18—to also consider the pleasure of performance and self-framing, as seen in works such as Maria Elena Buszek’s Pin Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Jacki Willson’s The Happy Stripper: Pleasures and Politics of the New Burlesque (London: I. B. Tauris, 2007), and Carr’s How Do I Look? Viewing Pleasure and Being a Showgirl (London: Routledge, 2018). ↵

- “See 4 months of Brett Kavanaugh’s calendar from 1982,” PBS News Hour, September 26, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/see-four-months-of-brett-kavanaughs-calendar-from-1982. ↵

- Carr, Viewing Pleasure and Being a Showgirl. ↵

- We are grateful to the Terra Foundation for American Art not only for this initial introduction and for supporting our respective PhD research programs but also for their support in facilitating a 2019 reconvening in which we built much of the scaffolding of this current project. ↵

- Film scholar Susan Felleman’s videographic criticism at the Chicago 2020 session included a compilation of provocatively juxtaposed film clips, including both fictional and biographical representations of female artists on film, from Artemisia (1997) and Frida (2002) to Rear Window (1954), Legal Eagles (1986), and The Big Lebowski (1998). Felleman’s analysis, now published in the online journal {in}Transition, reveals the ways in which these representations often pathologized the character of the female artist, offering them up as “cautionary tales”; alternately, she notes, films consistently represent women artists as “eccentric and ridiculous,” a source of either comic relief or menacing threat. See Susan Felleman with Hannah Shikle, “Four Ways to Be a Woman Artist . . . According to the Movies,” {in}Transition: A Media Commons Project with The Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies 9, no. 2 (2022), https://mediacommons.org/intransition/four-ways-be-woman-artist%E2%80%A6-according-movies. ↵

- This work has subsequently been published as Rachel Middleman, “Aging and Feminist Art: Joan Semmel’s Visible Bodies,” in Women, Aging, and Art: A Crosscultural Anthology, ed. Frima Fox Hofrichter and Midori Yoshimoto (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021): 167–81; Rachel Middleman, “Feminist Figuration: The Art of Joan Semmel,” in Joan Semmel: Skin in the Game, ed. Jodi Throckmorton (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2021), 9–35. ↵

- See also Rachel Middleman, “Collage as a Feminist Strategy in the Work of Anita Steckel,” in Legal Gender: The Irreverent Art of Anita Steckel, ed. Kelly Lindner and Rachel Middleman (Chico: California State University, 2018), 16–25. ↵

- Some of this work has been published: Marissa Vigneault, “Reading Hannah Wilke’s S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974–1982) in the Era of #MeToo,” in Iconic Works of Art by Feminists and Gender Activists, ed. Brenda Schmahmann (New York: Routledge, 2021), 87–101. ↵

About the Author(s): Ellery E. Foutch is an Associate Professor in the American Studies Program at Middlebury College, Vermont.