Sculpture and Lived Space

Most of us can appreciate the social uses to which sculpture is put when it is placed in the public sphere, including the use of public sculpture to promote cultural myths and shape collective memory. Whether or not sculpture is “public,” however, it is a rewarding subject of social art historical inquiry when considered as not merely a discrete object, but as an extension of the lived environment, in dialogue with the body and/or history. Sculpture, perhaps more than other forms of artistic expression, pointedly demands scholarly engagement with social space. Art historian Kellie Jones beautifully addresses the relationship between sculpture and literal and figurative space in her new book, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s. South of Pico is unambiguously not a “sculpture book,” but a book about black migrations and especially how African American artists’ movements, memories, and assertions of space were connected with the forms and material conditions of their art. Despite its broad scope, Jones’s effort, which examines how African American artists “carved out new landscapes in American art” and created what she terms “homeplace,” testifies to the unique role that specifically sculpture plays in the lives of both its creators and audiences.1

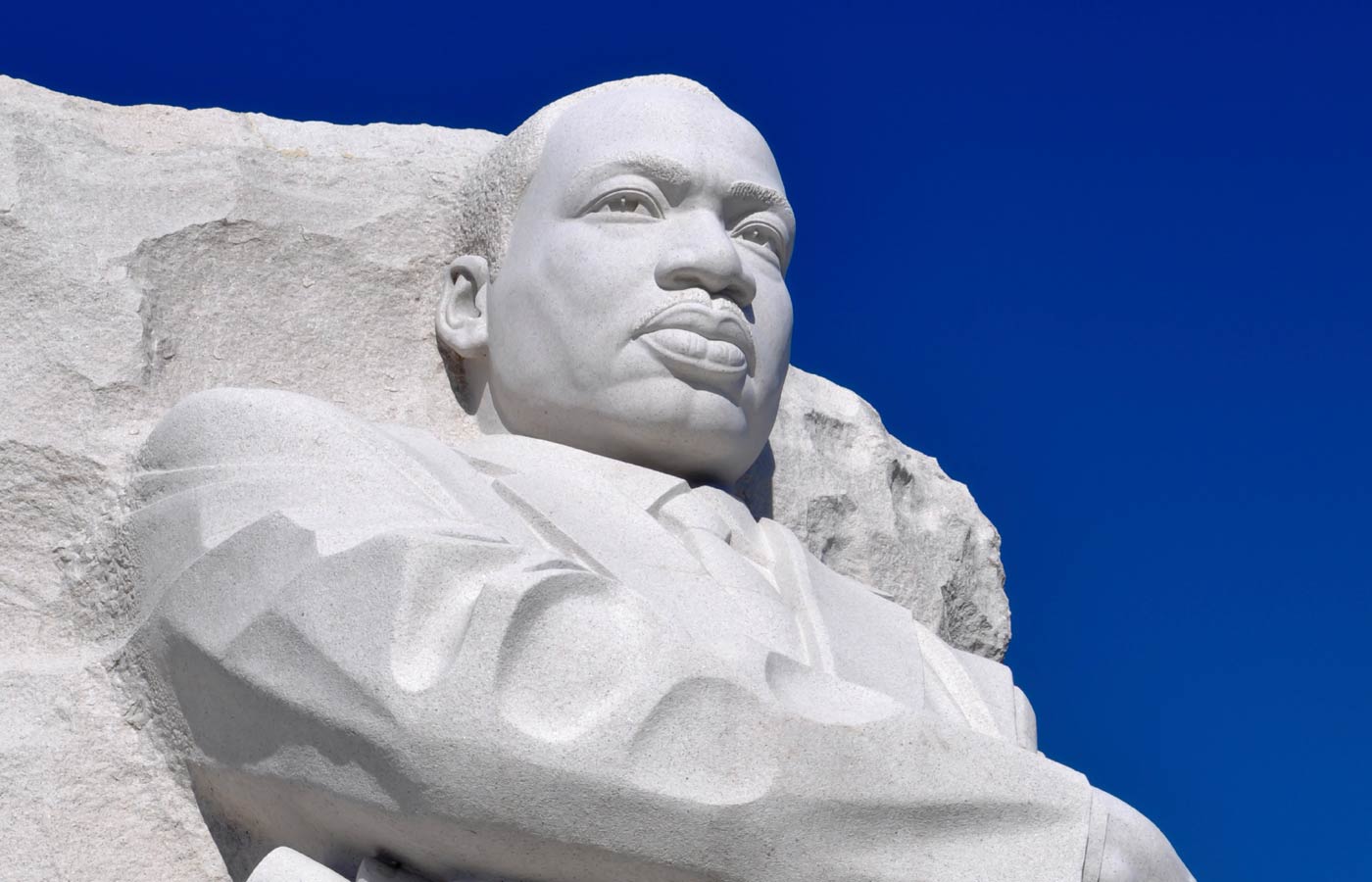

My engagement with sculpture emerged from an enduring interest in public art, a varied field in which sculpture is only one small part. While the larger field of public art expands well beyond memorials and traditional portrait statuary, these latter genres raise a distinct set of challenges and deserve special attention from art historians. A number of scholars continue to follow the lead of Kirk Savage, Michele Bogart, and Erika Doss to examine representational figurative sculptures. Dell Upton’s What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South is an important contribution.2 The endless political maneuvering and controversies generated by the projects that Upton covers will not surprise anyone who has researched the process behind public art commissions, in any region, but Upton’s examples forcefully demonstrate who steers the narrative of public history and why the stakes are so high. His chapter on sculptures of Martin Luther King, Jr., titled, “A Stern-Faced, Twenty-Eight-Foot Tall Black Man,” describes the different publics for King sculptures and the challenges at the heart of portrait statuary—including the misperception that sculpture can or should capture a “photorealistic” likeness of its subject. Divided opinion about public figurative sculpture appears at times to echo the nation’s current political divide, with people on either side of the issue unable or unwilling to speak one another’s language. In the gallery and museum realm of the art world, the relevance of figurative sculpture diminished in the 1950s and 1960s, but in the realm of public art, it is very much alive. As such, it demands intelligent appraisal, both of its form and of the circumstances of its process, as the recent, problematic installation of Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl on Wall Street underscores.

Figurative sculpture also has an intriguing funereal history, a story long marginalized until the late Cynthia Mills wrote her book, Beyond Grief: Sculpture and Wonder in the Gilded Age Cemetery.3 Cemetery sculpture is a field haunted by some of the same low-art associations as Civil War and World War I soldier memorials (and more recent war memorial statuary): commercialism, unapologetic copying, and sentimentality. It was Mills’s intelligent assessment of the fluid boundaries between high-art sculpture and low, as well as her attention to the meanings that sculptural reproductions accrue in popular culture, which helped encourage me to pursue my research on World War I memorial sculpture.4

In the area of memorial sculpture, Harriet Senie’s Memorials to Shattered Myths: Vietnam to 9/11 offers a refreshingly critical assessment of “victims’ memorials” and therapeutic memorials; a genre, she argues, that helps people feel better by obscuring the root causes of the tragedies they commemorate.5 Senie and Cher Krause Knight recently co-edited a volume titled A Companion to Public Art, in which they put forward a strong defense of memorials as art and thus argue for the consistent italicization of memorial titles. Senie and Knight explain that a memorial is “conceived and designed to communicate with its audience through a visual language, and likely one that builds on preexisting conventions and practices.”6 The editors of A Companion to Public Art also contribute to the discipline by mentoring a new generation of public sculpture scholars who are expanding the field in important ways. Marisa Lerer’s work on Argentina’s Parque de la memoria in Buenos Aires and Chilean memorials to the disappeared, included in Public Art Dialogue and in their volume, respectively, should be an integral part of Americanists’ frequent scholarly and classroom conversations about public memory.7

Senie and Knight founded the organization and journal of the same name, Public Art Dialogue, giving sculpture scholars another venue in which to explore this complex subject. The summer 2016 issue, guest edited by Erika Doss, included Sarah Beetham’s timely consideration of the fate of Confederate memorials in the era of Black Lives Matter. The article is related to Beetham’s book project, “Monumental Crisis: Accident, Vandalism, and the Civil War Citizen Soldier,” in which she traces the living histories of Civil War monuments. In Beetham’s article she concludes “it is time to reexamine the role of these monuments in American life” to determine at the local level, and with the input of professional public historians, whether particular Confederate memorials should be removed, relocated, or reinterpreted with the addition of sculpture or other interventions.8 Equally timely is La Tanya Autry’s reflection for the online Public Art Dialogue newsletter on the public interventions by performance artist and demonstrator Torrence Taylor. During the 2015 Maafa Commemoration in New Orleans (an annual gathering to respond to and recognize the transatlantic slave trade), Taylor performed at sites of public history, including one marking the statue of Edward Douglas White, a former Confederate soldier and Louisiana judge. As Autry argues, Taylor’s goal was to “recover and remake memory and the city.”9 Autry is currently completing a dissertation about contemporary memorials to lynching violence titled, “The Crossroads of Commemoration: Lynching Landscapes in America,” which promises to be another major contribution to the field of public memory. Looking at the links among public history, memorials, reenactment, and performance, Autry’s efforts, like Beetham’s and others discussed here, highlight the porous boundaries of sculpture studies.

In recent years, art historians have also endeavored to recover the fuller social and contextual meaning of post-war abstract sculpture. In Irrational Judgments: Eve Hesse, Sol LeWitt and 1960s New York, Kirsten Swenson recontextualizes her subjects within a “messy, varied, and broad account of art in New York,” in order to show how “the work of art could no longer be isolated as an object separable from the artist’s mind, her community, and the field of ideas preceding and following from its emergence into the world.”10 Likewise, as mentioned, Kellie Jones has recuperated and bestowed museum legitimation on African American sculptors working in an abstract and category-defying manner. Her Pacific Standard Time exhibition at the Hammer Museum, Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles (2011), and the exhibition she co-curated with Teresa Carbone at the Brooklyn Museum, Witness: Art & Civil Rights in the Sixties (2014), included, for example, works by assemblage artists, like Noah Purifoy, who appropriated cast off junk in the wake of the Watts Rebellion of 1965.11 Purifoy and his contemporaries in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, believed in art as an agent for change, and their emphasis on process resonates with today’s politicized artists who are interested in effecting a “social practice” or “dialogical art.” Ultimately, as Jones relates, Purifoy lost faith in art’s capacity to make a difference in the lives of the black poor. He retired from art to full-time social work, returning to sculpture only in the late 1980s when he relocated to Joshua Tree.12

Renewed optimism about the power of art to change the course of history is reflected in increased scholarly attention to the history of “social sculpture,” including the radical art of the 1960s and beyond. Sculpture is fairly well represented, for instance, in the Brooklyn Museum’s current exhibition, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85. Senga Nengudi, a cross-disciplinary artist who in the 1970s started making soft sculptures out of pantyhose and sand, is represented in the Brooklyn show, and is an artist whom Jones also examines in South of Pico. Performers have activated Nengudi’s flexible nylon forms in ways that referenced the possibilities of the feminist movement and also Nigerian “rituals of respectful celebration of the body.”13 The multi-media artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles received her first museum retrospective at the age of seventy-seven at the Queens Museum of Art last fall and winter.14 Ukeles’s practice emerged from her experiences as a mother and caregiver and grew to address the underappreciated labor of New York City’s sanitation workers. While her performances sometimes result in physical objects displayed as sculpture, they are the product of a larger conversation about the lived environment. Their aesthetic value is inseparable from that dialogue. The Queens Museum has established itself as a proponent of social practice, through a number of initiatives and thanks to the priorities of its former director Tom Finkelpearl and his successor Laura Raicovich. Not everyone will agree to classify Ukeles or Nengudi as sculptors first and foremost, or to accept social practice as art, and yet, revisiting the output of these two different artists—who have both made objects that relate to social systems in different ways—underscores the potential for working across media in art historical scholarship.

As my review of the above, highly varied scholarly efforts demonstrates, we would all lose if we neglected to study sculpture and the “plastic arts” alongside other media and practices, and vice versa. At the same time, many of these examples demonstrate sculpture’s continuity with lived social space, and thus its privileged role in exposing and forging connections among artistic expression, social experience, and the physical environment.

PDF: Wingate-Sculpture-and-Lived-Space

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1583

Notes

- Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Duke University Press, 2017), 15, 65, 97. ↵

- Dell Upton, What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). ↵

- Cynthia Mills, Beyond Grief: Sculpture and Wonder in the Gilded Age Cemetery (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2014). ↵

- Jennifer Wingate, Sculpting Doughboys: Memory, Gender, and Taste in America’s World War I Memorials (Surrey, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013). ↵

- Harriet Senie, Memorials to Shattered Myths: Vietnam to 9/11 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). ↵

- Harriet Senie and Cher Krause Knight, eds., A Companion to Public Art (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley, Blackwell, 2016), 42. ↵

- Marisa Lerer, “Chilean Memorials to the Disappeared: Symbolic Reparations and Strategies of Resistence,” in Senie and Knight, eds., A Companion to Public Art, 80-105. ↵

- Sarah Beetham, “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter’,” Public Art Dialogue 6, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 27. For additional perspectives on the Confederate sculptural legacy, see Evie Terrono, “‘Great Generals and Christian Soldiers’: Commemorations of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson in the Civil Rights Era,” in Kirk Savage, ed., Civil War in Art and Memory (Yale University Press, 2016), 147-170. ↵

- La Tanya S. Autry, “Fugitive Possibilities: The Black Image at Large,” Public Art Dialogue Newsletter 8, no. 1 (Fall 2016), http://publicartdialogue.org/newsletter/fall-2016/fugitive-possibilities-black-image-at-large, accessed April 7, 2017. ↵

- Kirsten Swenson, Irrational Judgments: Eve Hesse, Sol LeWitt and 1960s New York (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 6, 26. See also my review of Miguel De Baca, Memory Work: Anne Truitt and Sculpture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016) in Woman’s Art Journal 38, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2017): 51-52. ↵

- Catalogues accompanied both exhibitions: Kellie Jones, ed., Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980, exh. cat. (Los Angeles, Munich, and New York: Hammer Museum, University of California and DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2011); and Teresa Carbone and Kellie Jones, eds., Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, exh. cat. (Brooklyn and New York: Brooklyn Museum and the Monacelli Press, 2014). For a review of Witness by Erin Gray in Panorama 1, no. 1 (Winter 2015), see: https://journalpanorama.org/witness-art-and-civil-rights-in-the-sixties/ ↵

- Jones, South of Pico, 89-90. See also Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada, exh. cat. (Los Angeles, Munich, and New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2015). ↵

- Jones, South of Pico, 203. Nengudi and artist Maren Hassinger activated the sculptures at the Thomas Erben Galley (NY) and Pearl C. Woods Gallery (LA) in 1977, and more recently at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery in 2013 during the exhibition, Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art. ↵

- A catalogue accompanied the exhibition, Patricia C. Phillips, ed., Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art (New York: Prestel, 2016). ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer Wingate is Associate Professor of Fine Arts at St. Francis College