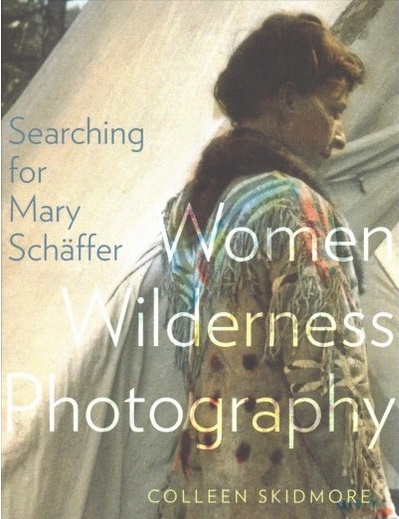

Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography

Colleen Skidmore

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2017; 376 pp.; 60 color illus.; 4 maps; ISBN: 9781772122985; Paperback: $34.95

In her meticulously researched study, Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography, Colleen Skidmore investigates the life and work of Mary Townsend Sharples Schäffer (1861–1939), a Pennsylvania-born painter, photographer, and travel writer who spent much of her career in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. While familiar to Canadian audiences, Schäffer is less well known in the United States. Skidmore’s monograph offers a robust introduction to Schäffer’s work and contributes to recent scholarship in American art that attends to work produced across the North American continent.1

In her meticulously researched study, Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography, Colleen Skidmore investigates the life and work of Mary Townsend Sharples Schäffer (1861–1939), a Pennsylvania-born painter, photographer, and travel writer who spent much of her career in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. While familiar to Canadian audiences, Schäffer is less well known in the United States. Skidmore’s monograph offers a robust introduction to Schäffer’s work and contributes to recent scholarship in American art that attends to work produced across the North American continent.1

Searching for Mary Schäffer is divided into five chapters; the first serves as a general introduction, and the following four examine Schäffer’s career in roughly chronological order. The first chapter sketches Schäffer’s biography and provides an overview of previous scholarship on her work.2 Skidmore distinguishes her study of Schäffer from prior publications in three main ways. First, Skidmore, a historian of North American photography and women’s photographic practices, prioritizes Schäffer’s prints, drawings, and photographs over her more studied travel writings. Second, she employs new archival sources made available to her by Schäffer’s family and friends. Finally, Skidmore rejects a biographical approach to studying Schäffer’s career in favor of methodologies derived from both the history of art and women’s studies. As Skidmore summarizes, “Taking up the challenge of rethinking the documentary view and use of Schäffer’s texts and photographs, both private and public, published and unpublished, that serve as the foundation of Schäffer studies, this book approaches the texts as crafted narratives and her photography as a fluid, collaborative, and creative gaze” (17).

In the second chapter, Skidmore considers Schäffer’s early career and focuses on the representations of plants and flowers that Schäffer created to accompany the studies undertaken by her first husband, Charles Schäffer, a Philadelphia-based physician and botanist who specialized in the flora of the Canadian Rockies. In vivid detail, Skidmore reconstructs Philadelphia’s lively scientific and artistic communities at the turn of the twentieth century, of which the Schäffers were a part (they were active members of both the Academy of Natural Sciences and the Photographic Society of Philadelphia). While frequently working in collaboration with her husband, Schäffer received independent recognition for her photographs when she was invited by the prominent photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston to display her work in an exhibition devoted to photography by American women at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900. As Skidmore notes, Schäffer’s specialization in the representation of flora enabled her to participate in the male-dominated fields of science and art while conforming to period conceptions of femininity.

The death of Schäffer’s husband in 1903 marked a turning point in her career and serves as the starting point of the third chapter. To honor her late husband’s research on the flora of the Canadian Rockies (and to boost her financial situation), Schaffer published her first book, Alpine Flora of the Canadian Rocky Mountains (1907). Illustrated and financed by Schäffer with text by botanist Stewardson Brown, the publication enjoyed popularity among both scientists and tourists. Following the success of Alpine Flora of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, Schäffer continued to explore and photograph the Canadian Rocky Mountains. These experiences are recorded in her best-known work, Old Indian Trails: Incidents of Camp and Trail Life, Covering Two Years’ Exploration Through the Rocky Mountains of Canada (1911), a travel narrative illustrated with photographs taken by Schäffer and her frequent hiking companion Mary (Molly) W. Adams. Working from unpublished letters, diaries, and photographs created by Schäffer and Adams, Skidmore analyzes how Schäffer crafted a narrative voice and visual style that captured the imaginations of readers in North America and Europe. This chapter is especially illuminating in its examination of the international networks of women, including Schäffer and Adams, who ventured together into the Canadian Rockies for sport and study.

Schäffer’s growing acclaim as an outdoorswoman led the Geological Survey of Canada to commission her to survey Maligne Lake in the Canadian Rocky Mountains in 1911. Schäffer’s “discovery” of the lake in 1908 and subsequent survey are the subject of the fourth chapter. In her search for Maligne Lake, Schäffer was guided by a map drawn by Sampson Beaver, an Ĩyãħé Nakoda hunter whom Schäffer had met and famously photographed along with his wife and daughter in 1906. Here and throughout the text, Skidmore refers to the Ĩyãħé Nakoda as the Stoney, a designation given by European settlers, rather than their preferred tribal name, a choice that would have benefitted from explanation by the author. Given the centrality of Beaver’s assistance to Schäffer’s expedition to Maligne Lake, Skidmore spends a considerable portion of this chapter discussing Schäffer’s relationships with the Indigenous peoples of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. While acknowledging that Schäffer’s descriptions of the Indigenous communities of the region were at times “disconcerting” and “startling,” Skidmore nonetheless insists that her photographs and writings worked to “dispel stereotypes” commonly held among Euro-Americans (164). In this case, the author’s admiration for her subject seems to have prevented her from more critically assessing the troubling colonial power relations that informed Schäffer’s representations of Indigenous people of the Canadian Rockies and her triumphant narrative of discovering Maligne Lake, known to the Ĩyãħé Nakoda as Chaba Imne.

The final chapter reviews the last three decades of Schaffer’s career, mostly spent in Banff, with particular attention to a tour of Japan that she made with Adams in 1908 and 1909. Schäffer’s voyage to Japan was primarily motivated by her success as a travel writer and her search for new subjects that would attract readers. In contrast to her excursions in the Canadian Rockies, Schaffer’s tour of Japan was focused on the urban environment. However, Schäffer did travel to Hokkaido and Taiwan to observe the Ainu and Atayal, indigenous people of Japan and Taiwan. Here Skidmore is more critical of Schäffer’s textual and photographic representations of indigenous groups and attends to the ways in which period “vanishing race” ideology informed her descriptions of the Ainu and Atayal. Although a largely successful trip, it ended tragically with Adams’s death after contracting pneumonia. The loss of her closest traveling companion marked the end of an adventurous chapter in Schäffer’s life, and she did not undertake any long-term excursions after 1909. Upon returning to Banff, however, Schäffer remained active as a writer and lecturer until her own death in 1939.

Through in-depth archival research, Skidmore develops a vivid portrait of Schäffer and her collaborative friendships with other women, especially Adams, who chose to lead unconventional lives at the turn of the twentieth century. At times, however, the text becomes bogged down as Skidmore introduces new archival evidence to clarify biographical details that have eluded previous scholars. Her attention to textual records left by Schäffer and her contemporaries occasionally overshadows her analysis of Schäffer’s paintings, drawings, and photographs. For example, Skidmore spends little time discussing the brightly colored lantern slides that are illustrated throughout the text and that Schäffer presented during lectures. It is unclear whether Schäffer’s color choices were based upon her observation in nature, aesthetic conventions of the period, or her personal taste. It also would have been useful to compare Schäffer’s lantern slides to the illustrations, both color as well as black and white, that appeared in her publications. Through a more sustained analysis of these visual records, Skidmore could have further developed her analysis of Schaffer’s photographs as “creative endeavours” instead of simply factual evidence of her travels (5).

Overall, Skidmore delivers an analysis of Schäffer’s prolific career as an artist and writer that will be of specific interest to scholars interested in the history of photography, women’s studies, and the history of science. In particular, her monograph serves as a useful foil to studies of Rocky Mountain photography in the United States, which are primarily concerned with the work of male photographers, such as William Henry Jackson, who are celebrated as independent and rugged pioneers. In Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography, Skidmore offers a refreshing alternative to other studies in her emphasis on the collaborative practices that Schäffer engaged in alongside other women who were drawn to the Canadian Rockies during the early twentieth century.

Cite this article: Katherine Mintie, review of Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography, by Colleen Skidmore, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1645.

PDF: Mintie, Review of Searching for Mary Schaffer

- A relevant example that focuses on representations of the North American landscape is Picturing the Americas: Landscape Painting from Tierra del Fuego to the Artic, eds. Peter John Brownlee, Valéria Piccoli, and Georgiana Uhlyarik (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). ↵

- Other studies devoted to Mary Schäffer (later Warren) include E. J. Hart, “Yahe-Weha—Mountain Woman: The Life and Travels of Mary Schäffer Warren, 1861–1939” in Hunter of Peace: Mary T. S. Schäffer’s Old Indian Trails of the Canadian Rockies, intro. and ed. E. J. Hart (Banff, AB: Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, 1980), 1–14, and Janice Sanford Beck, No Ordinary Woman: The Story of Mary Schäffer Warren (Calgary AB: Rocky Mountain Books, 2001). ↵

About the Author(s): Katherine Mintie is a postdoctoral scholar at DePauw University.