Marking an Era: Celebrating Self Help Graphics & Art at 50

PDF: Yale, review of Marking an Era

Curated by: Rochelle Steiner, Curatorial Fellow and Guest Curator

Exhibition schedule: Laguna Art Museum, August 19, 2023–January 15, 2024

Marking an Era: Celebrating Self Help Graphics & Art at 50 opens with Some Kind of Buckaroo (1990) by Jean LaMarr (Northern Paiute/Achomawi). LaMarr’s screenprint sets a Native American cowboy on an extraterrestrial landscape patterned with lace, beyond which the contrails of fighter jets cross a grape-hued atmosphere. Barbed wire fronts the scene, a none-too-subtle framing of the expanse within the settler colonial project of the United States. Referencing Native histories, LaMarr’s print aptly hangs adjacent to Cruising Turtle Island (1986) by Gilbert “Magu” Luján, one of the founders of the Chicano artist collective Los Four (fig. 1). Luján’s ambient, kaleidoscopic composition pairs the Native American name for the North American continent with iconography evoking Aztlán—the ancestral Chicanx homeland—and urban sites in contemporary Los Angeles. Together these works emphasize transcultural exchange and greet visitors to the Laguna Art Museum (LAM) with examples of the expansive visual lexicons of the Chicanx and Latinx artists—and non-Latinx fellow travelers—who expanded their practices at Self Help Graphics (SHG).

Sister Karen Boccalero, a Franciscan nun, founded Art Inc. in a garage in East Los Angeles in 1970, which then became the basis for a printmaking workshop and gallery when artists Carlos Bueno and Antonio Ibañez joined in 1972.1 After moving to a larger space in Boyle Heights, they renamed the organization Self Help Graphics in 1973. One of five exhibitions in Southern California celebrating the workshop’s fiftieth anniversary and highlighting different aspects of SHG’s practice and history, the exhibition at LAM focuses on a ten-year period of workshop production from 1983 to 1992.2 This period is bookended by two milestones. In 1983, SHG established the Experimental Silkscreen Atelier, which selected professional artists with limited experience in screenprinting to participate in a ten-week program. Paired with master printers, invited artists produced museum-quality screenprints; they kept half of their editions and donated the other half to SHG. In 1992, LAM acquired 170 prints from SHG, becoming one of the earliest institutional collectors of SHG and the largest public repository for Chicanx printmaking in the country. As the sole anniversary exhibition held at a collecting art museum, Marking an Era signals the continuance of the atelier program’s success at marshaling a market for Chicanx and Latinx prints in this period.

For this exhibition, curator Rochelle Steiner selected one print by each of the ninety artists in that landmark 1992 acquisition—the largest display to date—to celebrate the Experimental Silkscreen Atelier as an incubator of Chicanx and Latinx art and community-oriented printmaking. The first gallery brings together prints representing Indigenous resistance to nationalism. Dando Gracias (1983) by Leo Limón, an early participant in the atelier who taught stenciling to artists in later cohorts, portrays a woman donning pre-Columbian motifs offering a nopal cactus to the moon. This first gallery also addresses the hybridity of borderlands interrupted by a carceral immigration system. Alfredo de Batuc’s Seven Views of City Hall (1987) replaces the Virgin of Guadalupe with Los Angeles City Hall, a transmutation of Catholic iconography into municipal hostility toward immigrants from Central America seeking sanctuary in Los Angeles in the mid-1980s.

Works by artists who participated in Atelier XV, along with LaMarr, hang around a corner in a hallway opening onto the central gallery. Juana Alicia’s Sobreviviente/ Survivor and Michael Amescua’s Xólotl (both 1990) share LaMarr’s investments in tenacious figures and Indigenous histories (fig. 2). It is tantalizing to consider how proximity to each other’s practices—and the atelier’s works-in-progress meetings for all participants—might have informed the artists’ production of these three prints. For instance, Amescua’s composition includes expanses where lace was burned onto the screen, but in a more painterly manner than LaMarr’s graphic precision. Yet Marking an Era, which includes only object information on its labels, without interpretive text, gives little indication of just how the atelier program’s structure or SHG’s collegial atmosphere encouraged collaborative thinking among cohorts. Although screenprinting is a process of distributed artistic labor at SHG, the master printers who worked with artists during this period—Stephen Grace and Oscar Duardo—go unnamed, and their technical advancements in screenprinting are unexamined.

The exhibition is framed by four texts affixed to the pillars in the center of the main gallery, which address the history of SHG, workshop programming oriented toward community and social justice, the atelier program, and SHG’s position in relation to LAM’s institutional history. These texts stress both the hyperlocal context of SHG in East Los Angeles—its commitment to art education in the community—and its position as an epicenter of innovative printmaking and Chicanx and Latinx art in the global contemporary art world. The absence of additional didactic material, or archival documentation of the ateliers, poses a difficulty in that the exhibition demands the screenprints speak for themselves. Visitors are asked to see camaraderie, influence, mentorship, and community only through form and material, while also recognizing that the expansive visual lexicons of Chicanx and Latinx art resist categorization or essentialist narratives.

Each wall of the central gallery takes up one or two themes. On the far wall, artists appropriate images from a predominantly white, male art-historical canon, engaging a postmodern allegorical impulse. Guillermo Bert’s . . . And His Image Was Multiplied . . . (1990) reproduces the lightbulb from Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and the finger touch of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam (c. 1512) atop an inverted photograph of Filipino farmworkers. Mounting the farmworkers in a gilded frame and the Sistine Chapel on a dial-tune television set, Bert reverses the context of the two images and stresses the alienation of Western art history from the corporeality of globalized stoop labor.

Atelier artists also borrow more expansively, drawing on Chicanx popular culture and sharing in a practice of rasquachismo—Chicano scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s term that describes an oppositional Chicanx visual sensibility absorbing vernacular forms. Victor Ochoa references the Mexican board game Lotería; Vincent Bautista and Eduardo Oropeza depict calaveras (skeletons associated with Día de los Muertos); and Ester Hernández and Tony Ortega print portraits of painter Frida Kahlo (at the height of “Fridamania”). Prints that address historically contingent issues of social justice—displayed without context—are at risk of being defanged by the white cube. For instance, in the back right corner of the central gallery, Barbara Carrasco’s Self-Portrait (1984) reflects the artist’s outrage at the censorship of her mural in downtown Los Angeles three years earlier. Next to it, Diane Gamboa’s Malathion Baby (1990) is a condemnation of the city spraying pesticide on communities of color and of the consequent health risks.

A small room in the rear of the exhibition space seems to eschew thematic coherence with three prints—Sam Coronado’s The Struggle (1991), Reyes Rodriguez’s A Part of You and Me (1989), and Patssi Valdez’s The Dressing Table (1988)—that share a mostly formal affinity for serpentine forms and the female figure. The Dressing Table exemplifies what Chicana artist Amalia Mesa-Bains terms domesticana, a feminist redirection of rasquachismo present in the work of Valdez and others, with a tableau of wares for maintaining femininity (perfume, makeup, and a purse) and piety (a Madonna, rosary, and votive candle).3

It is disappointing that both the exhibition texts and labels are monolingual, appearing only in English. Art historian Mary Thomas recently described SHG as a cultural space that refuses the mainstream art museum’s normative assumptions of a racially homogeneous audience, modeling a decolonial alternative to the ideologies undergirding Western museums.4 Marking an Era reanimates, if only tacitly, urgent debates from the formation of these early ateliers about cultural agency and negotiation—what it means for the “mainstream” museum, and the federal government, to collect and exhibit Chicanx and Latinx art under the guise of multiculturalism. As early as 1980, Malaquías Montoya (whose 1989 print Sí Se Puede!/Yes We Can! is included in the opening room) pressed fellow artists on co-optation: “Had Chicano artists really not understood that the system that supported apartheid in South Africa and at the same time provided funds for the advancement of Chicano liberation had something up its sleeve?”5 In 1993, the United States Information Agency (USIA) sent a traveling exhibition—Chicano Expressions: Serigraphs from the Collection of Self Help Graphics—to South Africa and other postcolonial African countries. The exhibition, which later toured Europe and Mexico, was inevitably a compromised opportunity. The USIA leveraged the multiculturalism of the workshop’s program as a mode of soft power in non-aligned nations. Yet, because Sister Karen Boccalero curated the exhibition with the support of SHG artists, the tour duly recognized the Los Angeles workshop and Chicanx printmaking in a global conception of American art and culture.6

A major missed opportunity of this jubilant anniversary exhibition is that it sidesteps debates of the culture wars that coincided with the early years of the atelier program, thereby understating SHG’s resilience and ingenuity during this ten-year period. LAM’s acquisition of this body of work from SHG was finalized during Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (or CARA), the first major national art exhibition of Chicanx art, which traveled to venues across the United States from 1990 to 1993. If CARA was the first incursion of Chicanx art and culture into the mainstream museum world, what American studies scholar Alicia Gaspar de Alba describes as “the master’s house,” then LAM’s acquisition represents an early moment of habitation from within.7 This landmark acquisition—negotiated in 1991 at the height of the culture wars—was also made possible by the partial support of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), as the museum purchased the prints through an assembled pool of funds, with half from museum supporters Rene and Norma Molina and Charlie Miller and half from the NEA.8 The NEA also supported the early years of the atelier program directly through grant funding.

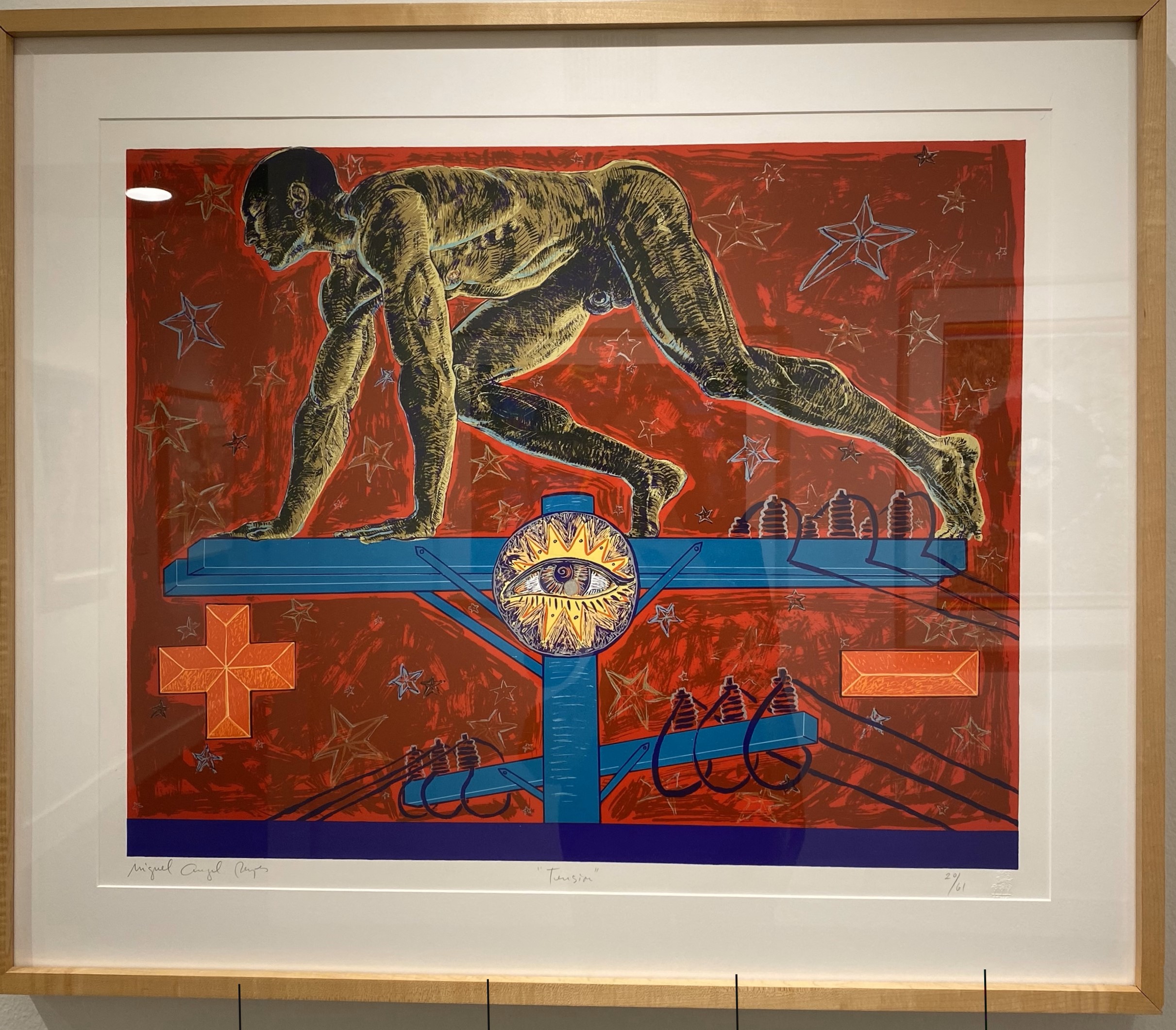

A small room between the opening gallery and the main space of the exhibition includes several works gravitating around sexual desire that presage the decency standards of federal patronage engineered by conservative politicians and enforced by Congress in 1990. Elizabeth Rodriguez’s untitled print (1986) borrows imagery from mass media to create a diptych of contorted bodies. On the adjacent wall, George Yepes’s Amor Matizado #47 (1989) is a tightly cropped, fleshy, and erotic image of two female-presenting individuals kissing. Yet the print that most openly reflects the primary bugbear of NEA opponents—gay male desire near the apex of the AIDS epidemic—is elsewhere, exhibited in a corner otherwise dedicated to portraiture. American studies scholar Robb Hernández has described Miguel Angel Reyes’s Tension (1991) as a nude jock preparing to run “to a beat in the time of AIDS,” destined to succumb to an infection he cannot outrun at the hands of a federal government indifferent to this crisis (fig. 3).9 Precariously balanced on a power line, the jock strains his chiseled muscles, exposing his genitals to the gaze of a disembodied eye below.

That Reyes’s print evades this thematic grouping, instead appearing among Jose Lozano’s full-face view of a luchador in Hero (1991) and Keisho Okayama’s abstracted Self-Portrait (1990) resembling a Noh mask, might reflect how SHG carefully maneuvered this period of heightened contention over public funding. In spite of cutbacks to state and federal funding for the arts in the 1980s and 1990s, and attendant decency standards, SHG not only prevailed as a subversive stronghold but developed a model for community-sustained artmaking in East Los Angeles that continues to thrive (even amid multiple relocations and intermittent closures). Under the intrepid leadership of Boccalero in its early decades, and following her untimely death in 1997, SHG has fostered radical care both for the artists who practice at the workshop and its local community.

The prints in Marking an Era are the products of a program that centers community by training professional artists in printmaking and supporting the growth of a market for the work of Chicanx and Latinx artists. Yet, the full range of SHG’s practice of social justice is ill suited for the institutional space of the museum. SHG’s politics are rooted in the relationships and communities that exist outside the picture plane: in its mobile art studio that brings a Chicanx worldview and arts curriculum to underfunded neighborhoods, in its annual East Los Angeles Día de los Muertos celebration, and in its exhibitions and special projects in the service of revolutionary, antihegemonic culture. Despite this incompatibility, Marking an Era provides visitors with a valuable opportunity to view prints that are as multilayered in artistic, cultural, and political commitment as they are laminated by color separations.

Cite this article: Margot Yale, review of Marking an Era: Celebrating Self Help Graphics & Art at 50, Laguna Art Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19037.

Notes

- These early dates are contested, but J.V. Decemvirale has recently located archival material that dates Ibañez and Bueno’s arrival to January 1972 in “Dibujando el Camino: Ibañez y Bueno and the Chicano-Mexican Public Art Tradition,” in Self Help Graphics at Fifty: A Cornerstone of Latinx Art and Collaborative Printmaking, ed. Tatiana Reinoza and Karen Mary Davalos (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2023), 54. ↵

- The other four exhibitions were Cultura Cura: 50 Years of Self Help Graphics in East LA, University of California, Santa Barbara Library, October 25, 2023–June 21, 2024; At the Heart of It: LGBTQ+ Representation at Self Help Graphics, Lily Tomlin/Jane Wagner Cultural Arts Center, November 18, 2023–February 10, 2024; Battle of the Saints, Long Beach City College Gallery, March 7–April 27, 2024; and The Re-Membering Generation: 1990’s LA Chicana/o/x Music, La Plaza de la Raza, April 6–June 8, 2024. ↵

- Amalia Mesa-Bains, “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache,” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 24, no. 2 (Fall 1999): 166–67. ↵

- Mary Thomas, “Generative Networks and Local Circuits: Self Help Graphics and Visual Politics of Solidarity,” in Reinoza and Davalos, Self Help Graphics at Fifty, 98. ↵

- Malaquías Montoya and Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya, “A Critical Perspective on the State of Chicano Art,” Metamorfosis 3, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 1980): 7. ↵

- Olga U. Herrera, “Self Help Graphics and Global Circuits of Art in the 1990s,” in Reinoza and Davalos, Self Help Graphics at Fifty, 231. ↵

- Alicia Gaspar de Alba, Chicano Art Inside/Outside the Master’s House: Cultural Politics and the CARA Exhibition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998), 22. ↵

- Zan Dubin, “Museum Acquires Chicano Works,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1991. ↵

- Robb Hernández, “Unfinished: The Death World of Homomobre LA,” in Reinoza and Davalos, Self Help Graphics at Fifty, 151. ↵

About the Author(s): Margot Yale is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Southern California