Cemeteries and Sculpture: “Ideal” Material Culture Pedagogy

The fields of material culture and sculpture studies have had an uneasy, if mutually respectful, relationship over the past few decades, during which the former has come into its own. In some ways, material culture and the study of decorative objects, where these two fields intersect with the study of sculpture, are still near the bottom of the “art historical hierarchy” that Jules Prown described in the early 1950s, when he began his studies in art history.1 For all the advances these fields have seen in the areas of scholarship and pedagogy, however, one large and rich area is still largely overlooked by practitioners in both milieus, and ignored by mainstream, “serious” art historians: American cemeteries.

As a graduate student in liberal arts at Harvard—I was interested in decorative arts, architecture, archaeology, history, society, and culture, so a “squishy” liberal arts degree seemed perfect—I discovered the field of study loosely defined as “material culture.” A paper in an art history course on a white marble sculpture I had fallen in love with at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—Arno, the Greyhound, by Horatio Greenough (1839)—inspired me to look more closely at early and mid-nineteenth-century American sculpture. Though considered a minor work in Greenough’s oeuvre, Arno turned out to be a gateway for me, developing into a fascination with nineteenth-century American sculpture. Often scoffed at by academic art historians through the mid-twentieth century for being derivative and trite, the earliest works of American sculpture produced by a nascent field of professionally-trained sculptors—Greenough, Thomas Crawford and others—were, to me, revelations of a veritable cornucopia of ideas, reflective of society, culture, politics, social hierarchy, art, and literature, embedded in the beautiful, buttery white marble of Carrara.

I certainly wasn’t the only scholar who was drawn to these works, which, yes, derived from Classical and European sources, and which, yes, were often produced in Europe, but which also, nonetheless, were considered “American.” William Gerdts’s seminal work, American Neo-Classic Sculpture: The Marble Resurrection, published in the early 1970s, was one of the first serious considerations of this time period in American sculpture.2 Other works followed, including Joy Kasson’s Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture (1990) and dissertations such as Lauren Lessing’s fine work exploring ideal sculpture in nineteenth-century American homes (2006).3

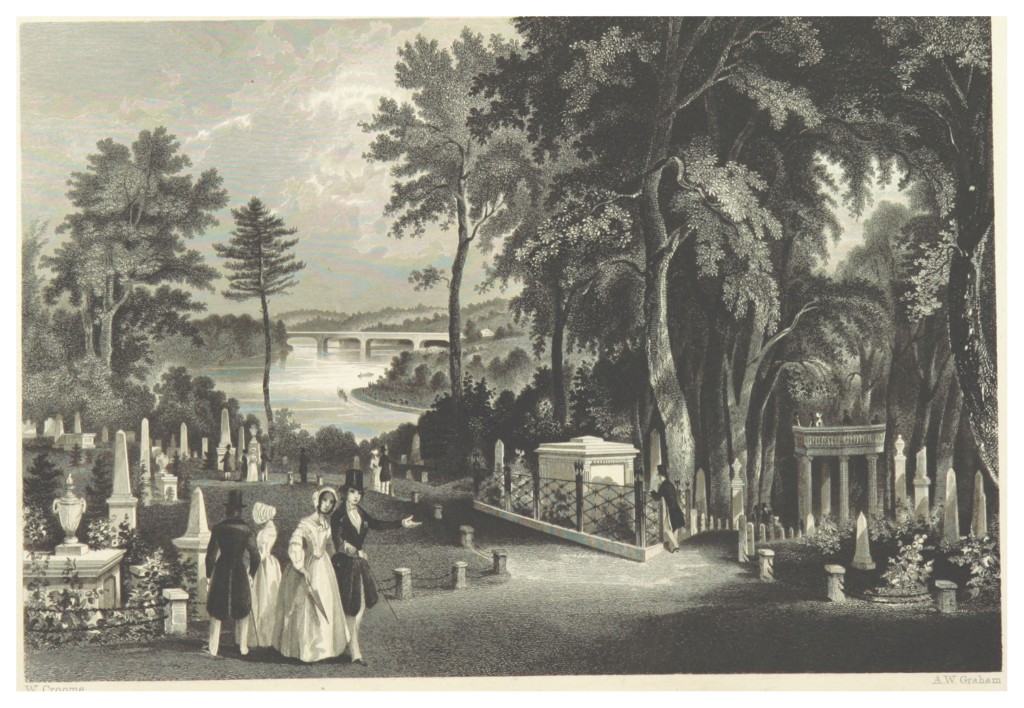

My own scholarly interests led to another home in the American nineteenth-century imagination: the heavenly one. I directed my attention to burial grounds, in particular those that formed part of the rural cemetery movement, a phenomenon that coincided with the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery in 1831. So-called Rural or garden cemeteries were designed as picturesque landscapes. These provided romantic settings for an increasingly varied array of commemorative and funerary sculpture. Realizing that many of America’s earliest professional sculptors sought commissions from cemetery lot owners, I focused on that for my master’s thesis. The sculptors I researched were the biggest names of the period—including not only Greenough and Crawford, but also Randolph Rogers, William Wetmore Story, and Harriet Hosmer—all of whom had worked hard to promote American-produced sculpture in the U.S., even though they received their training in Europe and in some cases, spent most of their professional lives there.4

In the course of my work, I also became aware of the importance of American stonecutters in introducing the seductive material of marble to the broad American public, well before Greenough’s first trip to Italy in 1825. Where was this material most visible? In graveyards and cemeteries, beginning in the late eighteenth century. White marble—both from Vermont quarries and Carrara, Italy—was more than just another material in the stonecutter’s repertoire. Marble became a central feature in graveyards of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, eventually all but supplanting the familiar slate headstones of earlier times. Stonecutters in urban areas wrote to each other seeking out the whitest slabs of “Italian” at the request of their customers, while marble achieved figurative significance in many of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s writings—almost becoming a character in its own right.5 My dissertation at the University of Delaware focused on white marble, stonecutters, and carved work for cemeteries from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries; there was no shortage of primary artifactual source material.6

For the scholar of material culture, sepulchral monuments represent a truly democratic form of art in the nineteenth century. Nearly every strata of society could afford at least a slab or small marker; middle and upper classes could afford a wider variety of memorial art. Marble monuments were the bread and butter work of successful, full-time professional nineteenth-century American stonecutters, as they would be for later generations of American sculptors such as John Frazee, whose early success was founded on cemetery work. All of the issues that art historians look at when studying the type of art that ends up in museums and other elite venues—private collections, galleries—are here in abundance in this funerary field: patronage, client, commission, negotiation, siting considerations, subject matter (or motif), and cost. Later in the nineteenth century, as monuments of granite largely replaced marble—which proved too fragile to last outdoors—architects, artists, and stonecutters refined their sculpting skills to that material, aided by newly developed pneumatic tools and diamond drill bits.

None of these more pedestrian facts—that stonecutters’ carving skills often matched that of trained academic sculptors, that powerful machines eventually replaced handwork (nearly impossible to perform on granite), or that people from all walks of life and social classes could view and appreciate ornamental carving—should cause concern for the art historian. Instead, these facts should be cause for celebration. Cemeteries are generally accessible landscapes; they are outdoor museums of sepulchral art, textbooks of art history. Initially horrified at the thought of going to a cemetery, many students in my art history survey courses came to appreciate the visual exercise of looking at monuments, memorials, and mausoleums to better understand what we discussed in class. To study the three orders of architecture, I took my students to Boston’s beautiful historic Forest Hills Cemetery, where, conveniently, three grand mausoleums side-by-side each exhibited a version of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns. Confronted with three-dimensional examples, students understood much more about the complexities of these architectural elements than any image or text could have taught them; they also learn that the obscure details of art historical connoisseurship structure the visual literacies of everyday life, not just museum-going.

There is so much we can learn of these monuments by asking the most basic of material culture questions: why does this artifact/object/work of art look the way it does? Most works of sepulchral art were carved by stonecutters and sculptors who are anonymous to us today, but by examining the works closely we can tease out many historical facets about contemporary thought, everyday life, popular culture, societal mores, and religious beliefs. Gravestones, memorials, and monuments are intentional, and specific to a family, a loved one, and a place and time. The person who ordered the monument and paid for it chose a particular design, in consultation with another family member, sometimes guided by the stonecutter or artist, who of course, knew what was appropriate to the style and ethos of the day. That the monument would be seen publicly—and possibly judged or commented on—gave extra incentive to both patron and sculptor/stonecutter to choose and execute wisely.

The fact that these monuments—to be sure, many of them grand, but many more on a smaller scale—are also still legible as expressions of emotion surprised many of my students. We all understood too well the meaning of rows of small headstones—to “little Willy,” “Our Baby”—which led to discussions about urban child mortality rates in the nineteenth century. Carved wilted flower buds—flowers that hadn’t the chance to blossom—conveys grief across the ages. Other motifs—botanical, religious, even domestic elements such as curtains—were open to interpretation, and led to lively debates among students. I also had the opportunity to introduce concepts I might not have had the chance to if we had stuck to a particular textbook, such as the idea of allegorical figures—the lovely statues of women wearing Greek chitons who embody abstract concepts such as Faith, Grief, and Hope.

The occasional article on a sepulchral monument in scholarly publications devoted to sculpture is a welcome addition to scholarship on American sculpture, but I believe there is still not enough emphasis on studying the lesser-known aspects of cemetery sculpture and monuments, including present-day cemetery gravestones. As the current editor of Markers, the scholarly, peer-reviewed journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies, I can definitely say there is much more life in cemeteries—if we only open our eyes and begin to ask the right questions, the monuments just might give us some very interesting answers.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1582

PDF: Ciregna Cemeteries and Sculpture

- See, for example, Jules Prown’s essay, “Reflections on Teaching in American Art History,” as well as essays by several of his former students and colleagues in the same issue. Panorama 2, no. 1 (Summer 2016): https://journalpanorama.org/reflections-on-teaching-american-art-history/ ↵

- William H. Gerdts, American Neo-Classic Sculpture: The Marble Resurrection (New York: Viking, 1973). ↵

- Joy S. Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990); Lauren Keach Lessing, “Presiding Divinities: Ideal Sculpture in Nineteenth-Century American Domestic Interiors” (Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 2006). ↵

- There were many reasons for this. Besides professional instruction, the proximity of Italian Carrara marble quarries and the existence of Italian stonecutters who were technical masters at replicating copies of works of art (replication of art was a more fluid practice and less controversial than it might be today) were both important factors in luring aspiring sculptors from the U.S. to Italy to live and work during the nineteenth century. ↵

- One of the most notable examples is, of course, Hawthorne’s Marble Faun, with characters loosely based on the actual American sculptors he knew in Rome, notably William Wetmore Story and Harriet Hosmer. But Hawthorne also wrote memorably about white marble in short stories such as “Chippings with a Chisel,” first published in 1838, and “The New Adam and Eve,” first published in 1846. ↵

- Elise Madeleine Ciregna, “The Lustrous Stone: White Marble in America, 1780-1860” (Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 2015). ↵

About the Author(s): Elise Madeleine Ciregna is the Editor of "Markers", a peer-reviewed journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies.