The Consultant: Paik’s Papers, 1968–1979

PDF: Jung, review of The Consultant

Curated by: Yoonseo Kim

Exhibition schedule: Nam June Paik Art Center Gallery 1, Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, October 13, 2022–March 26, 2023

Nam June Paik (1932–2006) was in many ways a pioneer and prophet of the technological age, hailed as the “godfather of video art.” The Nam June Paik Art Center of the Gyeonggi Cultural Foundation in Yongin-si, South Korea, is an institution that continues to shed new light on the artist’s legacy (figs. 1–2). It held a special exhibition on the ninetieth anniversary of Paik’s birth titled The Consultant: Paik’s Papers, 1968–1979. The show focused on Paik’s time in New York, when he worked as an official and unofficial consultant for the Rockefeller Foundation, rationalizing the support and development of video art over a period of about twenty years, starting in 1967.

The exhibition considered Paik as a policymaker based on three reports that he wrote between 1968 and 1979: “Expanded Education for the Paperless Society” (1968), “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Age: Only 26 Years Left until the 21st Century” (1974), and “How to Keep Experimental Video on PBS National Programming” (1979).1 These three reports are representative of Paik’s reflections on the future of education and media as influenced by anthropologists, economists, and futurists of his time, including American sociologist Daniel Bell (1919–2011), whose book The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1976) predicted the transition from a manufacturing economy to one based on science and technology.

The exhibition was organized into three sections, “Instant Global University,” “Electronic Superhighway,” and “Laboratory, Network, Museum.” They together demonstrated the relevance of Paik’s proposals for the present day. Compared to his achievements with the medium of video art, relatively little is known of how Paik investigated new avenues for social infrastructure. The exhibition urged the viewer to see Paik in a new light: the realization of his artistic vision was underpinned not only by public television and art institutions but also by collaboration with and support from private foundations, public universities, and commercial laboratories.

The first section, “Instant Global University,” was based on Paik’s 1968 report “Expanded Education for the Paperless Society.” He describes a fictional university where people of different cultures and languages create videos and send them back and forth by mail, suggesting that video can serve as a tool for learning about other cultures and resolving misunderstandings about national, social, and racial differences. In short, Paik was foreseeing the use of video in the age of the internet. While writing this report, Paik was conducting computer experiments as an artist in residence at Bell Telephone Laboratories and working as a communications research consultant at Stony Brook University in New York. At the time, Bell Labs was one of the most innovative scientific organizations in the world. Paik traveled between the university and the laboratory, meeting with students and engineers and attaining access to computers and pioneering technological equipment not yet available to the public. Later, his reports would reflect the experience of using the physical and intellectual resources of both the school and the laboratory and of coming in contact with people from different fields. These experiences are the basis of his view that art, as well as infrastructure, such as schools, libraries, and laboratories, should be easily accessible and shared by all, the ideology of open-source media and programming on the internet.

The main works in this section were Hacker Newbie (1994) and Highway Hacker (1994). Hacker Newbie represents the next generation traveling on the electronic superhighway. “Newbie” is a neologism derived from web culture, meaning a newcomer to the internet. “Hacker” is a person who engages in acts of changing the source of an existing program to make it different from the creator’s intention—in other words, a person who finds new uses for technology. The figure of a child robot sculpture holding an early game console is Paik’s vision of future generations born in the digital age. Highway Hacker is a robot face made of television monitors within a yellow traffic light and an upside-down antique radio case, each with an eye and a mouth. The images played on the screens are a superimposition of computer-generated pictures of roads, ships, vehicles, and other means of transportation and virtual highways. They are a metaphor for the social transition that interested Paik in the 1970s: the transition from a hardware-centered industrial society to a software-based information society.

The theme of the second section, “Electronic Superhighway,” referenced a term Paik coined in 1974 when commissioned by the Rockefeller Foundation to write the report “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Age.” It reimagines the US interstate highway system as a network of interconnected information, anticipating the internet before its commercialization. It is also the name of a large-scale exhibition organized by the Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art that toured the United States from 1994 to 1998. Paik’s overlap between road transportation and telecommunications urgently argued for a means to transmit and share ideas in real time, drawing a parallel between new information-based technologies and the economic revival that the United States experienced through the construction of highways in the 1930s.

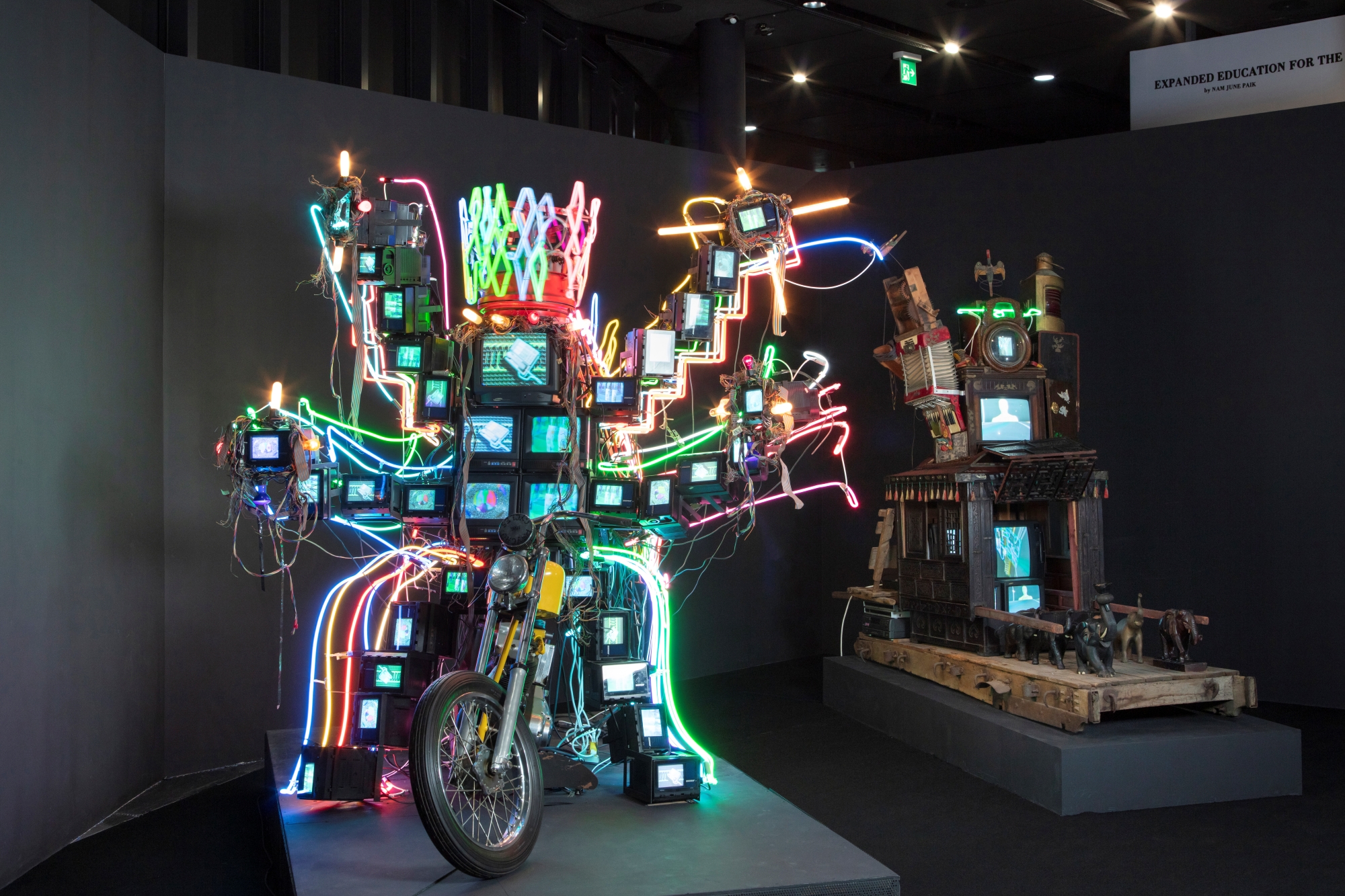

Paik used the metaphor of transportation as representing manual models of carrying information to envision a “broadband communication network” of technologies, such as video telephony, fax machines, and interactive television. The centerpiece of the second section was Elephant Cart (fig. 3), a large-scale sculpture of an elephant pulling a wheeled cart carrying a Buddha statue seated in a plastic chair, shielded underneath an Adidas umbrella. The cart is piled high with televisions, radios, and gramophones. Measuring 248 inches across and 118 1/8 inches high, Elephant Cart presents the animation of video and audiovisual information along its length, combing a mix of new and old media and asking viewers to reflect critically on the ways we communicate. Robot on Sedan Chair & Robot on Motorcycle (fig. 4) consists of a pairing of robots, one seated in a sedan chair palanquin to represent the past and the other on a motorcycle to represent the present. While one robot seems to wait for its attendants to supply the mobilizing lift, a web of neon lights makes up the robot on the motorcycle, symbolizing the extreme speed and joy of driving on today’s electronic superhighways.

The last section investigated the importance of public television as a laboratory, network, and museum, referencing Paik’s 1979 essay “How to Keep Experimental Video on PBS National Programming” (fig. 5). From the late 1960s through the 1970s, Paik worked with the Boston-area public television station WGBH-TV to showcase a variety of works, including Electronic Opera #1 (1969) and his contribution to the first broadcast video art program produced in the United States, The Medium Is the Medium (1969). This program was the result of the enactment of the National Endowment for the Arts in 1964 and the Public Broadcasting Act in 1967, which defined television as a tool for disseminating the arts to the public, significantly increasing its support by the government. Private foundations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation, also funded public broadcasting stations. During this period, Paik’s videos were broadcast on public television channels, discussed academically, and exhibited, collected, and disseminated in museums. Paik helped pave the way for many other artists to create work that was subsidized by the station system.

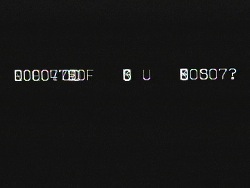

Paik’s use of a research laboratory began with his residency at Bell Labs, where he was able to conduct his own experiments in 1967. Digital Experiments at Bell Labs (fig. 6), presented in the third section, is an experiment that Paik created using an analog computer, the GE-600. The video, which consists of seemingly meaningless numbers and dots, shows a dot (a single pixel) jumping randomly along a diagonal line. At the end of the film, a garbled, unprogrammed data dump of text appears, and the upside-down word HEAD flashes intermittently. This experiment fascinated Paik with the idea of a programmed computer producing unexpected results within its parameters to generate new images. His laboratory experiments then extended to public television with works such as Electronic Opera #1, where Paik deconstructed the visual and aural grammar of television to establish a radical syntax for video, just as he did for Bell Labs.

This last section also summarized Paik’s overall contributions as a consultant. My Faust-Autobiography (1989–91) is a magnum opus that encompasses the concepts that interested him. Based on the nineteenth-century novel Faust by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the work expresses Paik’s insights into the history of world civilization. It is an excellent representation of Paik’s views on the key elements of social change and the social role of artists. Paik mentioned thirteen themes of art, education, agriculture, transportation, and communication in his 1974 report, which were influenced by Bell’s diagrams of the major elements in periods of social change.2 In the work, twenty-five televisions filled with chaotic images are installed inside a structure that borrows the form of a Western Gothic church or altar, with another monitor and antenna at the top. On the surface of the structure is a collage of laser discs, newspaper articles, letters, and musical scores, along with old cameras, video recorders, and old-fashioned telephones, all of which represent new and old media of communication and information. Each object resonates with a deeply personal record of Paik’s life, and the work synthesizes the worldview he has long sought to realize through his collaborations with museums, universities, and laboratories.

Paik’s reports are not only about media art as an art form but also about society shaped by new media and the policies necessary for this change. His proposals included video exchange as a tool to connect different cultures, digital revolution to record and advance history, the electronic superhighway as a communication system across the world, and the production of diverse public broadcasting content. These were concrete measures to solve social problems through art. At the same time, he developed a critical artistic practice that challenged political systems. Boris Groys summarizes art activism as having two main agendas: first, to criticize the dominant political, economic, and artistic systems; and second, to use art to mobilize the public to transform society from within and without.3 While Paik’s artistic output reveals and disassembles the social system through art’s inherent aesthetic autonomy and imagination, his reports are demonstrative of the imagination that pushes society beyond the fixed, structured, and instrumentalist uses of media technology. Thus, his reports have important implications for artists who carry on this practice today.

On the day Bill Clinton was elected president, he voiced in his inaugural address his goal of making the United States a nation of fiber-optic information superhighways. Shortly after Clinton’s announcement, Paik pointed to the impact of his work on the policy with the exhibition The Electronic Super Highway, Bill Clinton Stole My Ideas (1996). Clinton’s use of the term leads to the question, “What would happen if artists took over television?” Paik’s television program Medium Is the Medium featured his Electronic Opera # 1, which showed a distorted image of Richard Nixon. This piece exposed television as a powerful environment for the construction of mass political hegemony, while also pioneering its transformation to an interactive medium.

The assembled works in the exhibition at the Nam June Paik Art Center demonstrated that Paik’s impact went beyond television, to the very foundations of the internet. Paik saw television as not only the site where politics and representation intersected to capture people’s hearts and minds but also as a major obstacle to American democracy. Paik broke into this superficial world, enumerated the spectrum of visual tactics of the networked age, and reappropriated video as a powerful performative medium, as a device for the dissolution of spatial barriers, and as a democratic mode of communication. The core value of Paik’s work as both an artist and a consultant was to develop video as a solution to society’s problems, as a means to bridge gaps between global regions through the democratic communication and education made possible on television, and later, the internet. As the exhibition made clear, he was an activist.

Cite this article: Sera Jung, review of The Consultant: Paik’s Papers, 1968–1979, Nam June Paik Art Center Gallery 1, Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17465.

Notes

- Nam June Paik, “Expanded Education for the Paperless Society,” Magazine of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, UK: no. 6 (1968); Nam June Paik Papers, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Nam June Paik, “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Age: Only 26 Years Left until the 21st Century,” 1974; an excerpt of the English original was published as Electronic Super Highway: Travels with Nam June Paik (New York: Holly Solomon Gallery and Hyundai Gallery; Fort Lauderdale: Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art, 1994), accessed April 27, 2023http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/source-text/33. Nam June Paik, “How to Keep Experimental Video on PBS National Programming”, Independent Television-Makers and Public Communications Policy (New York: Rockefeller Foundation, 1979), 5–26. ↵

- Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (New York: Harper Colophon, 1974). ↵

- Boris Groys, “On Art Activism,” e-flux Journal 56 (June 2014), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/56/60343/on-art-activism. ↵

About the Author(s): Sera Jung is Founder and Director of THE STREAM Korean Video Art Archive Platform and Lecturer at Pusan National University in Korea